Remote Work Is Inexorable

Because It Offers What Most Stakeholders Want

Remote work:

Will it take over the world?

Will it disappear after the pandemic?

Depending on whom you listen to, it’s either inevitable or impossible.

"I don't see any positives [to working from home]. Not being able to get together in person, particularly internationally, is a pure negative."—Reed Hastings, CEO of Netflix.

“The 9-to-5 workday is dead; and the employee experience is about more than ping-pong tables and snacks"—Brent Hyder, president and chief people officer of Salesforce.

“[Remote work is] an aberration that we are going to correct as soon as possible.”—David Solomon, CEO of Goldman Sachs.

“We are now in that future world where the benefits of remote work outweigh the costs.”—Adam d’Angelo, CEO of Quora

Which one is it, people?

I decided to figure it out for myself. Here’s what I found:

People are talking about different things. Who can work remotely? What does remote work even mean? What are the timelines of remote work growth?

Those who say they prefer the office are not the same people and companies as those who say they prefer working remotely. There are clear patterns in who prefers what.

There are two key drivers of remote work in the long term, and both point in the same direction.

The consequences of remote work are life-transforming and society-shattering.

Let’s dive in.

1. What Jobs Can Even Be Remoted?

Not all of them. You can’t imagine remote police, hairdressers, or dog walkers1. Today, only knowledge workers can be remoted, and not even all of them. How do we know which jobs can be remoted?

It depends on their tasks. The more tasks a job has that can be done remotely, the more likely it can be remoted. From a McKinsey analysis:

Which means that only a subset of industries and jobs can be remoted.

In advanced economies like the US or EU, around 30%-50% of jobs can be remoted. In emerging economies like China or India, it’s more like 10%-20%. The jobs that can be remoted, however, tend to pay much better, so the impact on any given economy will be outsized when people work remotely.

I’ll refer to remotable jobs as knowledge work from now on, to simplify.

It’s important to know the distinction between what work can be remoted and what can’t because it affects survey results. Sometimes, you will see surveys of all types of companies (including on-site types of work). Obviously, these companies won’t support remote work for all their employees, so the result might be “only 20% of work will be fully remote”. Conversely, some surveys will include only people who worked remotely during the pandemic. These jobs are by definition all remotable already, so the results of these surveys will skew in the opposite direction. That’s where headlines like “60% of employees will work remotely” come from.

2. What’s Remote Work Though?

One of the main problems with the discussion around remote work is that people are conflating types of remote work. There are three:

Hybrid remote work (number 2) is convenient, but it’s not hugely life-changing: people still have to live close to the office, and the company can always retreat from its policies.

The dramatic change happens with number 3, when all work is remote: that’s an irreversible change that allows people to live wherever they want and companies to hire people from anywhere.

This matters, because most statistics refer to remote work as some or all work being remote (types 2 + 3), whereas others only consider it to be remote work when all work is remote (only type 3) and workers don’t step into the office 2 3.

So from now on I’ll refer to full category number 1 as “office work” (whether distributed or not), number 2 (working in the office a few days a week) as “hybrid”, and fully remote work as simply “remote”. I’ll also use “remote” as a verb. For example, a company can remote its jobs or workforce. A position can be remoted. And so on.

3. What Timelines Are We Talking About? The Adoption Curve

Lots of people might not realize they simply disagree on when remote or office work will be the norm. Like most technologies, remote work will go through its hype cycle:

We can probably agree that:

Remote work started slow.

There was a huge spike of remote work for knowledge workers in March 2020 across the world.

This spike is slowly receding as ventilation improves, measures are taken to minimize risk, and vaccines hit. Nobody questions that 2021 will be the year of the return to the office.

The question is how much. We have not yet reached the floor of that return. Many more people who will eventually go back to the office are still working from home.

But there will be a floor. So the first question is: How low is that floor?

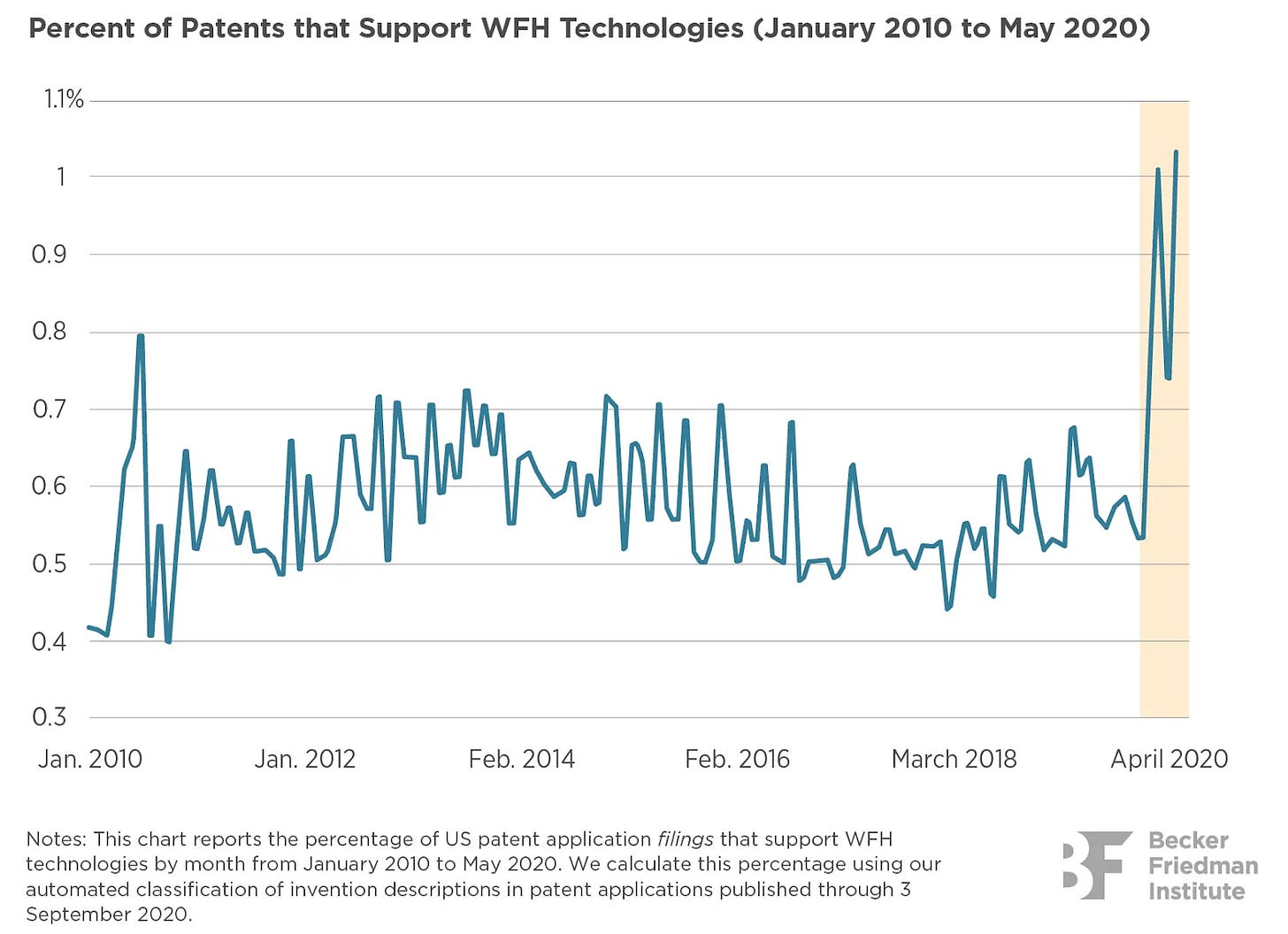

Remote levels will increase from that floor, as some companies and people realize remote worked well, as better tools for remote work get developed, and as productive remote companies grow. That’s the 2nd question: How fast will remote work rates go back up?

Then that trend will slow down too, because there will be a ceiling (or a series of ceilings) that prevent some knowledge workers from going fully remote. That’s the 3rd question: What’s the ceiling for remote work?

This narrows down the remote work problem to three questions: what’s the floor, what’s the ceiling, and how fast will we go from one to the other.

Let’s look at the numbers so far. Before the pandemic, about 6% of all employees could work remotely in the US, rising slowly from ~5% at the beginning of the 2010s.

During COVID, that share went up to ~34% in the EU4, and could have gone as high as 62% in the US5. Again, that’s of all workers.

It’s very unlikely that we go back to 6% in 2022, but it’s also unlikely we maintain 30%-60%. My guess is that, in 2022, 10%-25% of all employees in Western developed economies will work remotely. That is huge. Tens of millions of people will change their working habits forever, and that’s just the beginning of what’s coming next.

How do we know how these numbers will grow from hereon? Remote work is an agreement between two parties: companies and workers. The future depends on what each of them wants. Let’s start with workers.

4. What Do Knowledge Workers Want?

Wake up too early. Rush to shower. High heels. Tight tie. Skip breakfast.

Two-hour commute. Twice a day.

Miss the train. Wait 20 minutes for the next one.

Get packed in like sardines. Hear somebody cough behind you. Not able to move. 30 minutes to your destination. The AC is broken.

Arrive at the office.

Back to back meetings. No time to sit and think.

Get ignored because you’re the short one. Nobody knew that on Zoom.

That big mouth is flexing again, though. He rushed to sit at the head of the table, talks as much as he can, takes all the space. That didn’t happen on Zoom either.

Try to decipher body language cues. You’re on the spectrum; these neurotypicals make no sense.

Go to an empty room to connect to Zoom anyways. Some workmates are remote today.

Look for Selma, your boss. She’s not here. Maybe working from home today?

The food that disappears from the fridge.

The sound of your coworkers chewing.

The pile of dirty dishes.

The smell of food left in the trash.

The glare of the lights above you.

The headphones to steal back an inch of intimacy lost. And to fend off Brad, who will interrupt you anyways.

The cold of the thermostat, set for the body temperature of men at a time when women were an afterthought.

The smell of fresh poop flooding your nostrils when stepping into the restroom.

Look down the stalls to see which ones are empty. Recognize Bob’s shoes.

Walk further to find a good stall. Look up. Your eyes flicked through the slit of the door and met Jimmy’s horrified look of intimacy violation.

Find a stall. Clean it up. Something’s sticky. Second pass. Sit. Hold the noises. Hear all the other poopers. The one frantically tapping on his screen, surely playing a videogame. The one eating McDonalds, squirting for 20 minutes.

Call incoming. Your kid is sick. Your nanny must leave. Your dog escaped. Your delivery is early.

Pack up.

Two hours to go back to a small, overpriced apartment you can barely afford, picked because it was close to a semi-decent school.

Miss dinner with the kids.

Laundry.

Netflix and cry.

Rinse.

Repeat.

Does this hit home?

Maybe it’s the reason why surveys asking knowledge workers what type of setup they would prefer are consistent.

Notice that about ~30% of knowledge employees want to work fully remotely, and a tiny ~5% want only the office. This is already telling us that the full-time office we knew, where we could always go there and reliably meet all the people we needed to see… that office is dead. It doesn’t exist anymore.

Remember this when you hear opposite statements like:

“70% of workers want to get back to the office.”

“95% don’t want to ever go back to the office full time.”

Both of these statements are true. They’re co-opting the number of people who prefer hybrid work for their cause.

Also, remember that these results are not during normal remote but during pandemic remote, the worst time to be in an office!

What will these numbers look like when remote work is an order of magnitude better than now?

Before the pandemic, remote workers reported being 22% happier than office workers. They reported less stress, more focus, and better work-life balance.

Guessing why is not hard. Remote workers make more money6, have lower costs, less commute time, more time with the family and other hobbies, more convenient work setup, more time flexibility, can live anywhere…

Chris7 puts it nicely:

So at least 30% of workers want to work fully remotely, up to 95% want some remote options, and this is what workers think from experiencing remote work during an experience which was quite stressful. The numbers of those who want remote can only go up8.

If workers want remote, what do companies want?

5. Which Companies Want Remote Work?

Within knowledge companies, which ones do you think are more willing to keep the old office-based system?

Take a guess.

Here’s mine: Incumbents.

If you were winning in the past, why would you put that at risk? Success in an industry frequently comes from a culture and processes that are very hard to replicate, even to comprehend. If you are already winning and have so much at stake with a change that you’re not sure is going to work, why would you do that?

That’s the context in which Goldman Sachs’ approach should be framed when its CEO David Solomon said:

“[Remote work is] an aberration that we are going to correct as soon as possible.”

Or when JP Morgan’s CEO Jamie Dimon said:

“We want people back to work, and my view is that sometime in September, October it will look just like it did before. [...] And everyone is going to be happy with it, and yes, the commute, you know, people don’t like commuting, but so what. [...] Remote work doesn’t work for those who want to hustle.”

But of course the CEOs of the biggest banks in the world want everybody to come back to the office! That’s what they know! That’s what made them successful! Put yourself in their shoes:

He looks down the window at Manhattan. He turns around and, as he exits, he reads:

“David Solomon, CEO.”

It looks good.

He walks towards his private dinner room. People see him in the hallway, blush, say hi, and move to clear the passage. His best friends and colleagues are already waiting for him and a five-course lunch.

“If we went fully remote, we wouldn’t have these lunches anymore. Would we keep this building? This floor? Would I keep my office? My name?”

As he walks, he ponders: “Employees seem productive remotely, but there’s been more tension than normal. There’s that employee who turned out to be working for another company at the same time. A few left us, slamming the door on their way out. So many complained about long hours. They didn’t as much when they worked in the office. We had the camaraderie of all-nighters together, bathed in wine and sushi. Now people complain that there’s too many meetings. Zoom fatigue. Too much to write. To comment on. Slack, gDocs, email, JIRA, Asana… Too many channels, too many messages, too many notifications. No whiteboarding or happy hours, too many bad reviews, baby interruptions, dog interruptions, back injuries, mental health days—or whatever it is that these Gen Z babies demand nowadays… Wouldn’t it be easier to just go back to where we were?

On one side, it would be simpler. People come back, everything resumes. We know how to deal with old problems. That’s why we’re the best in our industry. Our culture is our magic sauce. Why would we jeopardize this with an experiment?

If some people leave, so be it. Candidates gather at our gates begging for jobs. We have our pick! We won’t have a problem finding more talent since we only hire 5% of candidates. And we print money, so the savings from hiring remote workers are probably not worth the headache and the risk. Plus there’s the paperwork: the taxes in every state, in every country; the countries that force you to incorporate; to follow crazy local labor laws. We’ve honed our tax avoidance over centuries. Are we going to start from scratch?

No. Remote work is an aberration that we are going to correct as soon as possible.

Most incumbents will think that way.

The companies that won’t are those fighting for talent.

If you’re a small startup struggling to find candidates with your unknown brand and puny salaries, but you know your big fish competitor doesn’t offer remote work, what’s the first thing you’re going to do?

Even if you’re a big company, but you’re struggling to hire given the war on talent, what are you going to do? The most daring companies, like Coinbase, Twitter, or Square, declare they’re remote first and open up their candidate pipelines. The more conservative ones and the biggest incumbents will be more cautious.

Like Google, which told its employees: “Everybody must go back to the office”. They backtracked two weeks later though. If a $1.5 trillion company with arguably the best offices in the world can’t convince workers to work in its offices, how can other companies win this battle?

Maybe Apple. It receives more candidates than it can process, and it just inaugurated a $5B headquarters, carefully designed by Steve Jobs himself down to the level of detail of the season when the wood for the panels should be harvested. Since Steve Jobs is not here to redesign the remote experience, and those left are no Steve Jobses, how could they achieve a comparable pinnacle of work experience going remote first? (update: confirmed)

So the more a company is an incumbent, the better it works, the more it is established, and the riskier it is to move to remote first. The opposite is true of startups.

Here we can see on the x axis that upstarts will have a big share of remote workers, while incumbents will instead have a majority of office workers.

Which one will win the fight for talent: upstarts or incumbents? It will all boil down to two things. The first decisive factor is what we discussed: What workers want. If the best employees choose remote, and upstarts offer it, they will attract the best talent, eventually beat incumbents, and remote becomes the standard. Incumbents will eventually cave and offer it too.

The second decisive factor is the only thing that truly matters to companies: employee productivity.

If remote companies are more productive, they will win market share. As they do, a bigger share of employees will work remotely.

We already looked at how workers want remote work. The last question we need to answer then is: which workers are most productive, those working remotely, or in office?

6. Which Workers Are More Productive: Remote, Hybrid, or Office?

Nobody knows yet. But we’re not clueless either. Let’s make some educated guesses.

Productivity is the value created divided by its cost. Let’s look at costs per employee and then the value they create.

Costs per Employee: Remote vs. Office

For companies, the cost of remote is substantially lower than in office:

1. Wages

A Kansas software developer makes 45% less than a San Francisco one9. Salary disparities are quite steep even within the US. If you recruit abroad, the savings are even steeper.

2. Real Estate

Each employee costs companies ~$20k per year in real estate in the US. Remote work replaces that with a ~$2k setup at most. On average, US companies think they can save 20% of their real estate and resource usage costs.

3. Other Costs

By encouraging employees to work remotely, companies can also reduce their benefit costs, such as food or commuter benefits. Business travel will be decimated, saving companies money in travel costs. Even more interesting, killing their headquarters allows a company to move to a more tax-friendly state or country, reducing their tax burden.

Note that most of these costs are only really saved if the employee is fully remote, not just hybrid.

I haven’t seen a full quantification of cost reductions with remote, but we don’t need one. Let’s assume for simplification that 30%-50% of costs per employee can be saved with remote work. That means that if remote workers were 30%-50% less productive than office workers, they would still be worth it. So how does the value generated by workers compare between remote and office?

Employee Value Created: Remote vs. Office

Before the pandemic, a Chinese company improved its call center employees’ productivity by 22% with remote. That’s the best scientific analysis I saw pre-pandemic.

The coronavirus didn’t allow for formal statistical studies on the impact of remote work, but every company is assessing how they’ve done, and most companies have seen their productivity grow.

According to UpWork, 32% of hiring managers found that productivity has increased (vs. 22% who found that it decreased). In a PwC survey, 83% of US executives considered remote work to be a success. 52% thought their companies were more productive. In another survey, 94% of employers think productivity was the same or higher (67% the same, 27% higher). Another survey suggests an increase in productivity of 15-40% with optimized remote models. And many more:

Best Buy, British Telecom, and Dow Chemical have seen that teleworkers are 35-40% more productive.

JD Edwards teleworkers are 20-25% more productive than their office counterparts.

American Express workers produced 43% more than their office based counterparts.

Compaq increased productivity 15-45%.

It’s not just employers. Workers agree. According to a BCG survey, 75% of employees working remotely report being able to maintain or improve productivity on their individual tasks. According to another survey, 51% of workers believe that they have been more productive working from home during COVID-19, and 95% of respondents say productivity has been higher or the same while working remotely. 90% of Dropbox employees feel they can be productive at home. Before the pandemic (2018), 65% of people thought they worked best at home (vs. 3% less productive).

So both employers and employees think remote work increases productivity. What might cause that increase?

Why Is Remote Productivity Higher?

Turnover

Because people are happier working remotely, employee turnover (those who leave the job and must be replaced) is 10-15% lower. Turnover is very costly, because a company loses the worker’s knowledge, and in parallel needs to train a new one from scratch.

Absenteeism

There are 40% fewer missed days. Flexibility to work from whenever means even when employees or their family members are sick, or there’s some inconvenience, people can do at least some work.

Commute

The commute is eliminated, and ~35% of that time is dedicated to work. At Sun Microsystems that figure is 60%. AT&T workers work five more hours at home than their office workers.

Intangibles

There are also lots of other reasons for higher productivity that are harder to quantify but are perceived as real by workers. According to a survey of employees:

Fewer interruptions (68%)

More focused time (63%)

Quieter work environment (68%)

More comfortable workplace (66%)

Avoiding office politics (55%)

I’d add to that asynchronous communication, which is much better for analyzing and giving feedback than live, on the spot.

This Is Just the Beginning

Let’s pause for a sec.

The old way of working has been around, evolving, for centuries.

Then, one day, all of mankind wakes up and starts working in a completely different way, a way that had never been tried before.

And it’s more productive!

What will it be like in a few years, when we learn the social conventions of remote, and we develop tools that will boost our productivity?

The Bright Future of Remote Work

Why is remote work inexorable then?

Because companies want productivity, and workers want freedom.

Remote provides both.

How will it unfold? As the pandemic wanes, people will go back to the office.

Or so will companies try.

Many employees want remote work.

And they’re more productive this way.

That gives them a lot of negotiation power.

Initially, there might just have 2-3 times more remote workers than before the pandemic. But it will grow from there as their productivity will become evident to companies, and employees will realize the dramatic improvement in quality of life, from asynchronous work to rural living, a hobbies renaissance, remote retreats that are actually fun, more family time, closer ties with your local networks, more bullshit task automation, lower costs…

As the advantages become obvious to all, and productivity further increases through better tools and know-how, we will see one of the biggest changes in work since the Industrial Revolution.

The ramifications in the economy and society will be dramatic, from crumbling business real estate costs while suburban and rural real estate goes up in price, to a tax war between countries to attract nomad talent. From a massive hollowing out of the middle class of knowledge workers in developed economies to an increase in inequality. And much more.

In upcoming articles—some of them premium—I’ll dive into these ramifications, as well as the nuances of remote work: generational interplay, network effects and feedback loops of remote vs. office, diseconomies of scale of the office, the canary in the coal mine of remote work, asynchronous work, the main upcoming challenges for remote, and much more. Sign up to receive it!

Some of these will come, but it will take a few years / decades.

There’s also the type of work that requires a few days every month or every quarter in the office. I put this type into category 3—full remote work—because employees can still live far away and travel every few weeks / months to spend a few days in an office.

Some companies differentiate between “remote” and “distributed”—by which they mean “in offices we have in different places, not necessarily headquarters”. “Distributed work”, to me, is simply office work. Any company that grows enough has had to open new offices anyway. And it forces people to still work close to a designated office, so there’s nothing special there. Also, this is all doubly confusing because depending on whom you ask, “remote” and “distributed” mean this or the opposite. This is confusing.

I’m using US and EU27 numbers. They aren’t perfectly comparable—notably poorer EU areas are much poorer than the US, and have much less remote work potential—but good enough.

42% of working-age people were working from home, an additional 26% were working on-premises, and the remainder were not working. The 62% is 42%/(42%+26%)

Controlling for other factors

Chris Herd is the CEO of a company that helps other companies set up their employees for remote work. As such, he is biased. His company benefits from remote work. But as a person who consistently talks with companies interested in remote work, he’s a reliable source for the insights of that segment.

Some people want to go to the office. Usually, the main reason they use is because they miss the colleagues or leaving home. But a good local community and a cozy work environment are two things remote can do better, because you’re not forced into one office and one set of colleagues. Remote work doesn’t mean always working from home. You will be able to work in different settings. And you’ll be able to decide who you want to hang out with.

Source: Comparably. Tech Engineering Developers for companies between 200 and 500 employees, in San Francisco vs. Topeka, Kansas

Thank you, Tomas, for another great article. Here are some observations from my work experience at a large incumbent company and a government agency.

(1) Knowledge workers hate cubicles but, inexplicably, cubicles have become the norm. Telework is great for escaping the cubicle environment where people use speakerphones and raise their voices in "shouting matches" with concurrent users of speakerphones.

(2) Knowledge work is difficult to measure, and knowledge workers frequently resort to appalling tricks such as writing documents that are too long and creating PowerPoint slides that have too many irrelevant graphics and "eye charts" instead of clear summaries.

(3) Managers [in large incumbent companies] don't know how to rate knowledge work. Their main heuristics are: (a) whether an employee comes in early and leaves late, (b) the gross volume of an employee's products (documents, PowerPoints), and (c) whether a manager (or his boss) likes this employee.

(4) When I teleworked one day a week, I was required to be continuously connected to a chat and respond immediately. This state of constant readiness has largely depleted the advantages of escaping the commute and the cubicle.

(5) Hybrid solutions seem optimal, BUT they are usually more complex and carry a large overhead. As you wrote in the article, a hybrid worker can't move to a low-cost-of-living area. Coordinating meetings and deliverables of hybrid workers is more difficult than having either "office" or "remote" employees. Managing, rating, and promoting hybrid employees is more difficult. For example, an employee who comes to the office on the same days as her manager does gains some privileges due to subconscious sense of connection.

Victoria

A thought-provoking article, but I think it is a bit one-sided as it doesn't discuss several factors in favor of working from the office:

1) Employees need socialization and like leaving home (at least from time to time).

2) Long-term productivity such as creativity and integration of complex projects may be less effective when working remotely.

3) When working remotely, employees miss the exchange of ideas that takes place in corridor/water-cooler/cafeteria informal meetings.

4) It's harder to build a company culture when employees are remote. Remote employees may be less attached to the company and more prone to hopping between jobs.