Dubai

The Anti-Petrostate

What will happen to petro-states after oil demand dries up?

How can countries be successful in the 21st Century?

Dubai answers both questions, but not the way I thought before I visited the city last year.

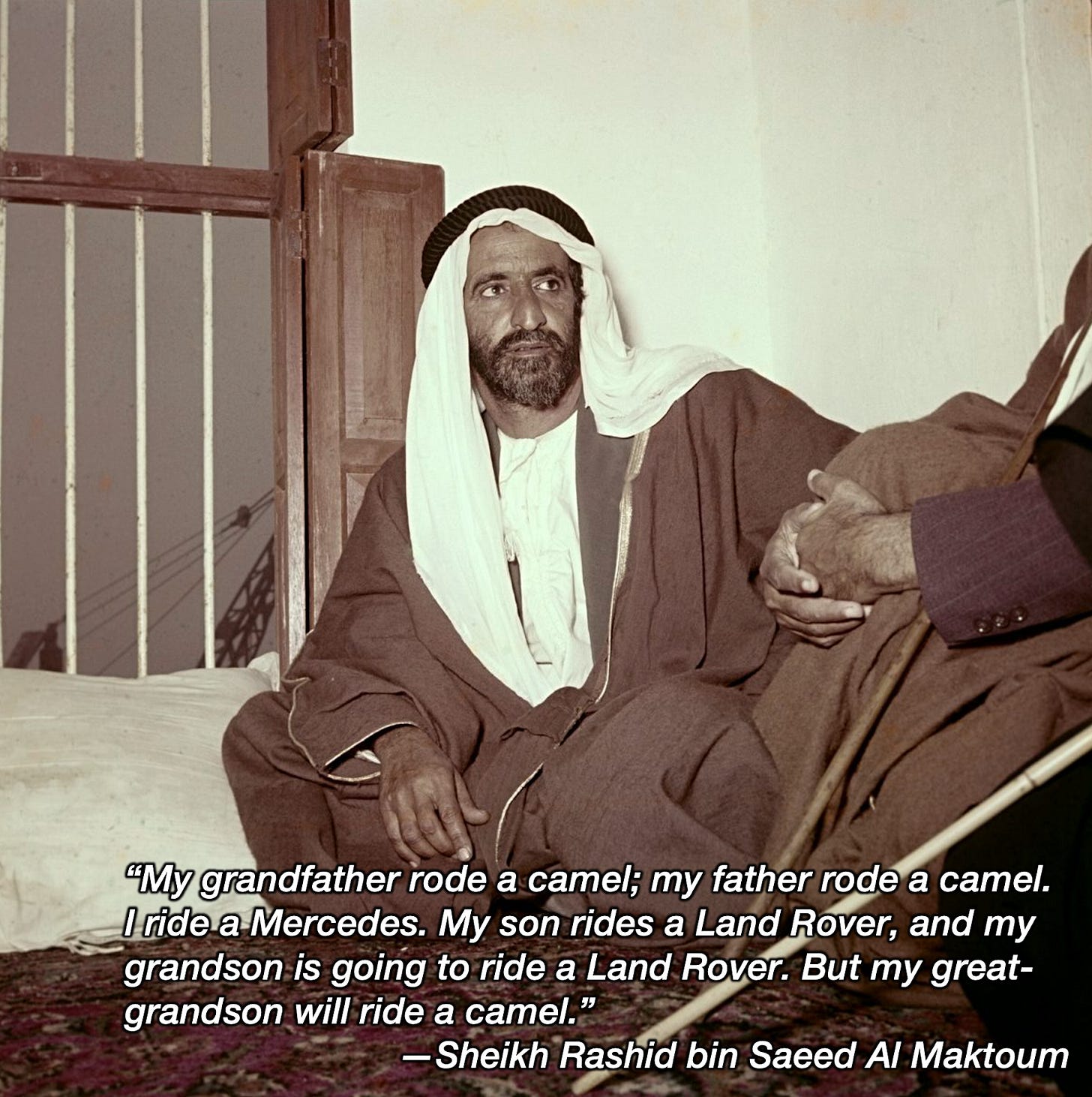

My grandfather rode a camel; my father rode a camel. I ride a Mercedes. My son rides a Land Rover, and my grandson will ride a Land Rover. But his son will ride a camel.—Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, founding father of the UAE and ruler of Dubai.

Dubai faced an existential crisis.

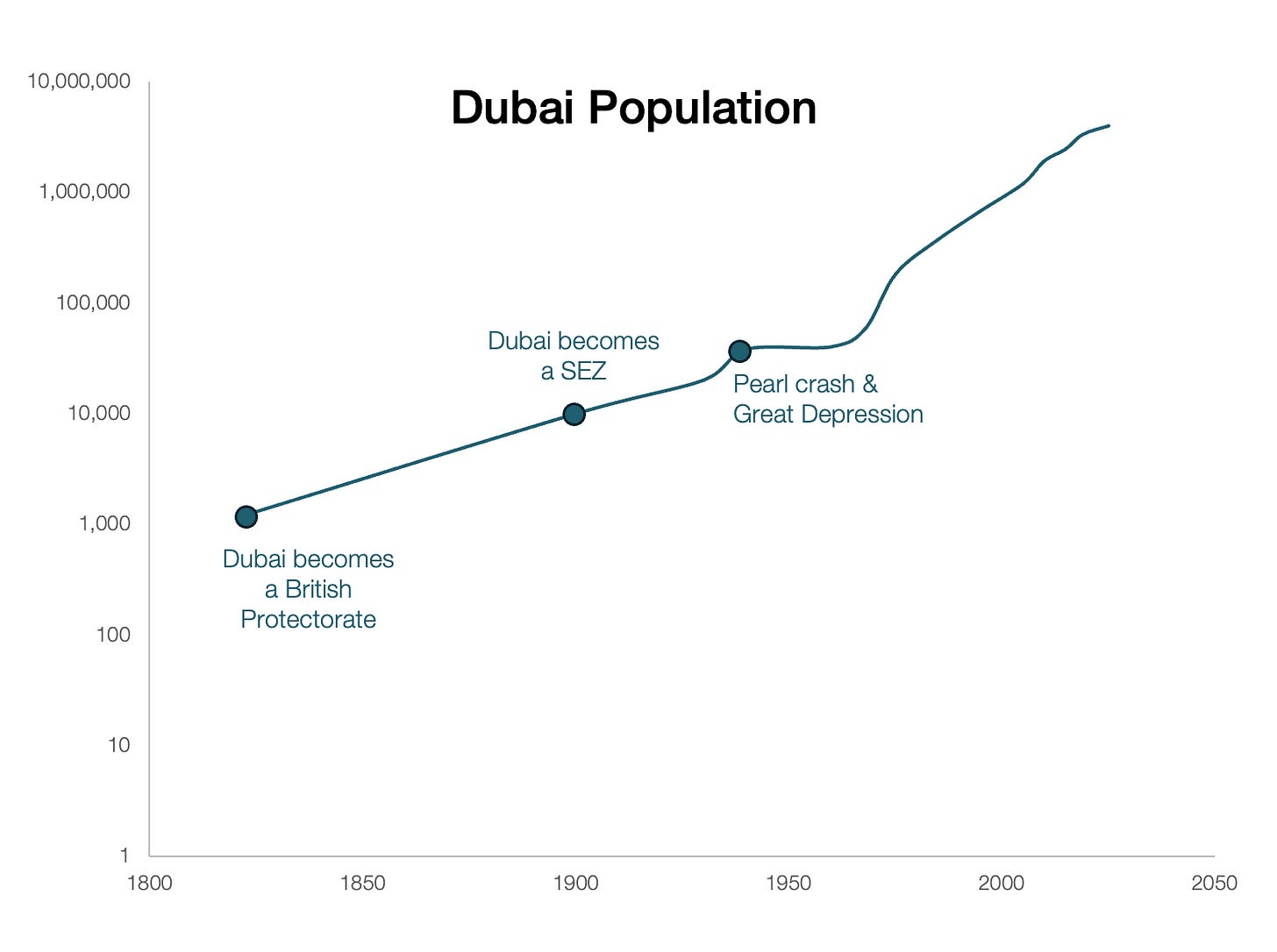

In 1900, it was a village on a coastal creek in the middle of the desert and hadn’t changed much for centuries.

By the 1950s, it was still a small port city.

Then, it found oil.

But not much. The rulers knew it wouldn’t last long.

If Dubai was going to be anything, they had to act fast.

They had to use this oil as intelligently as possible.

That was the vision of Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, and he succeeded beyond his wildest dreams.

Today, Dubai is not only a bustling city. It’s one of the most dynamic city-states on Earth, and an example of what can be done to fight the curse of dwindling oil revenues.

This is how I see Dubai after studying it and visiting it: How it started, how it got where it is today, and what lessons others can learn from it.

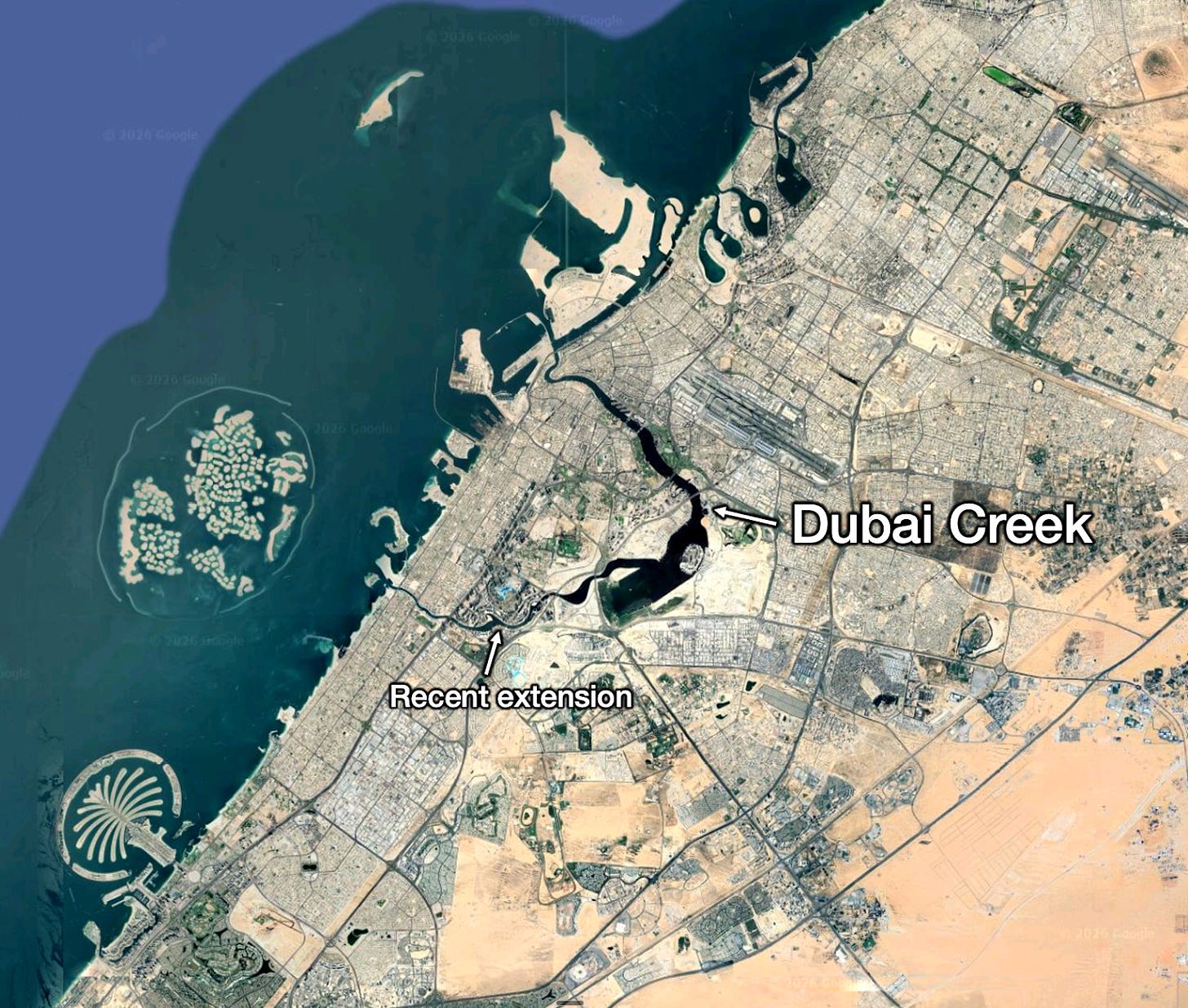

Dubai Creek

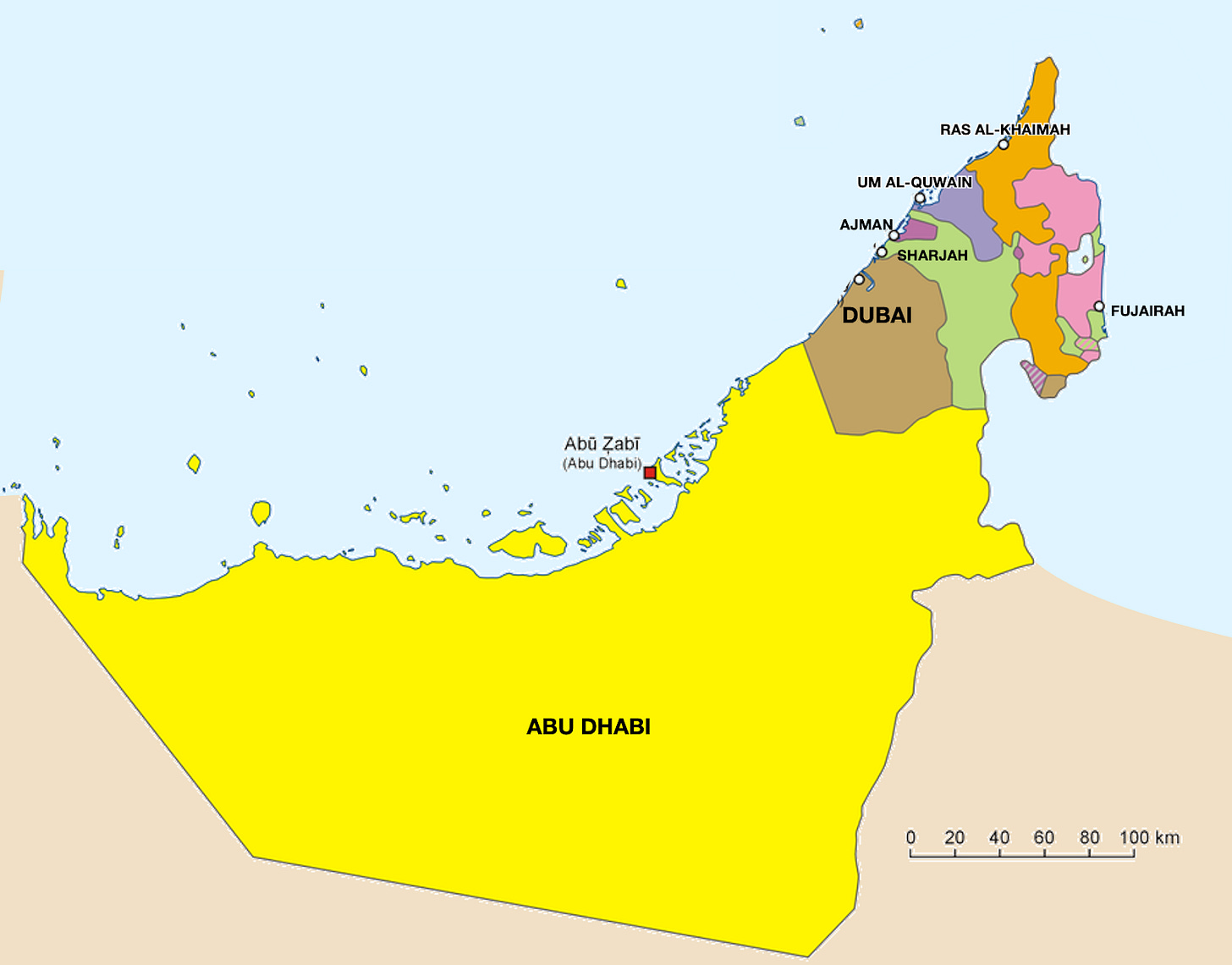

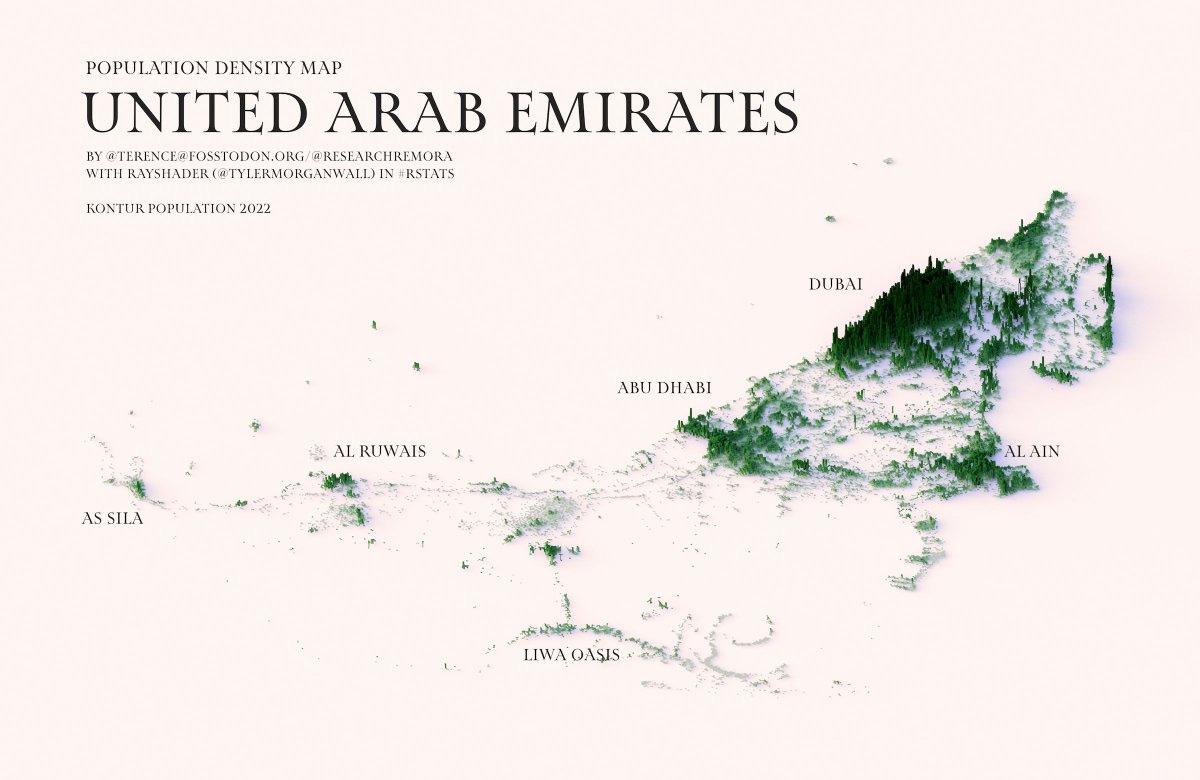

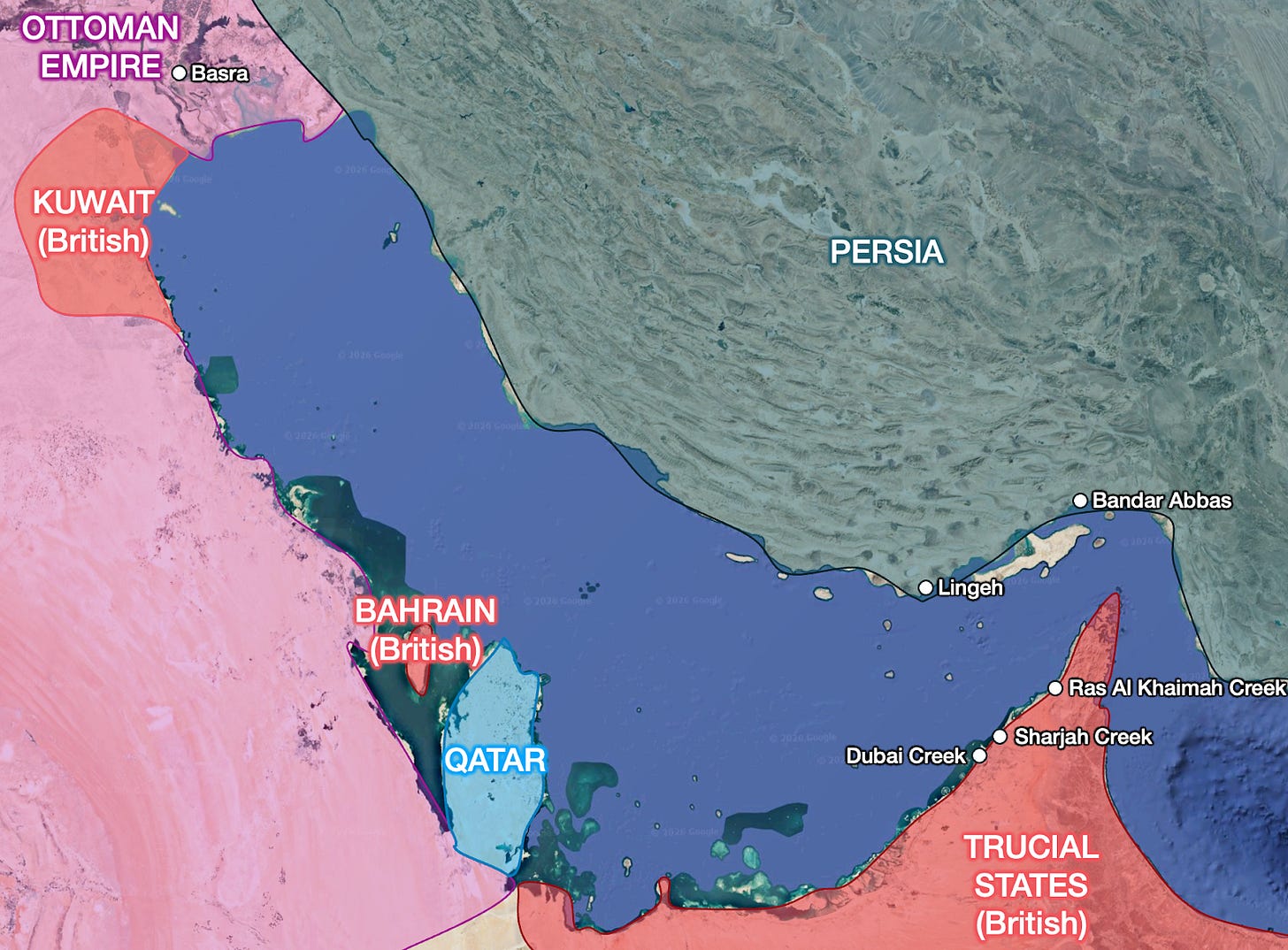

Dubai is one of the United Arab Emirates, on the Persian Gulf.

Dubai is the second biggest of the seven emirates of the United Arab Emirates.

But it has the biggest city.

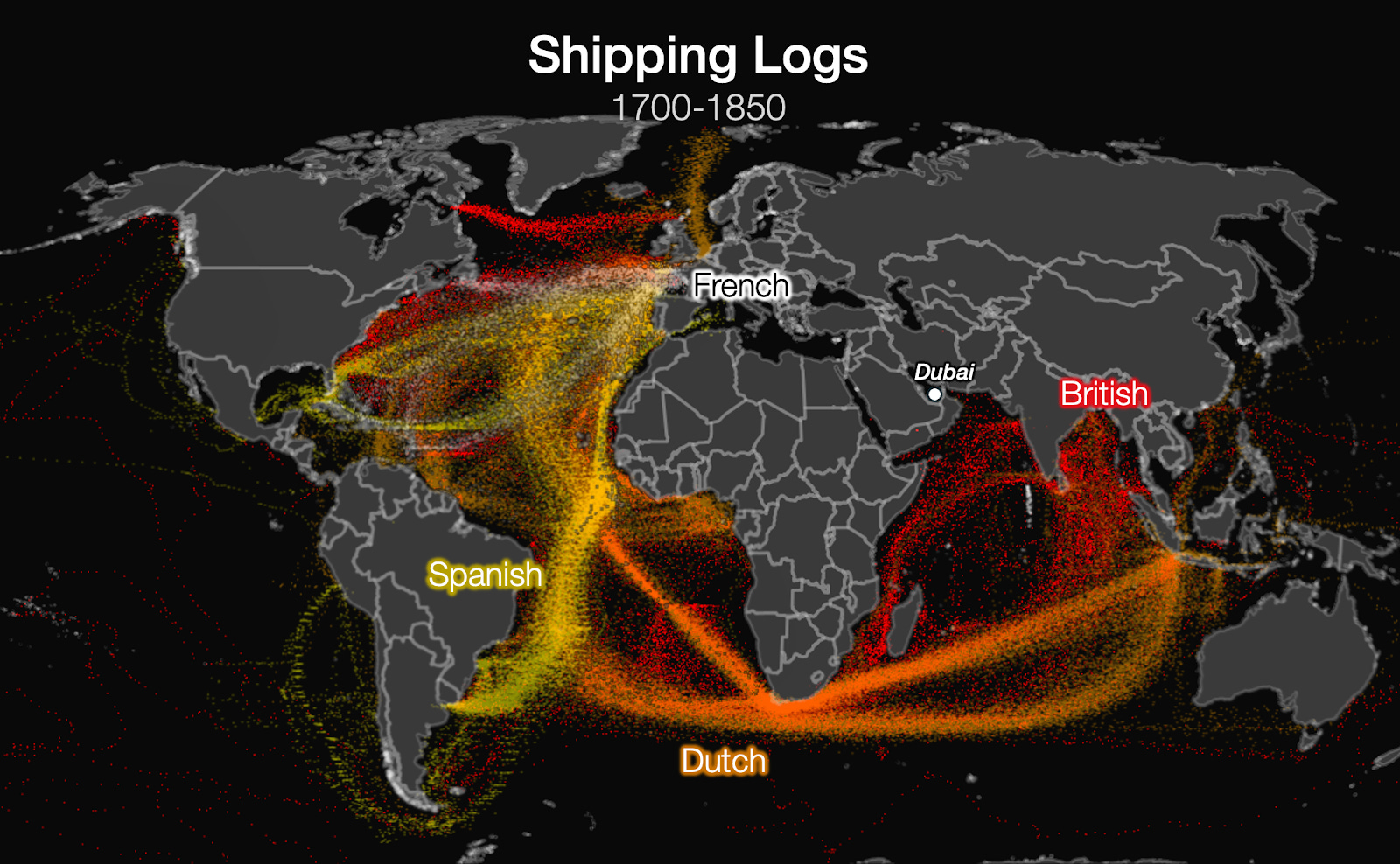

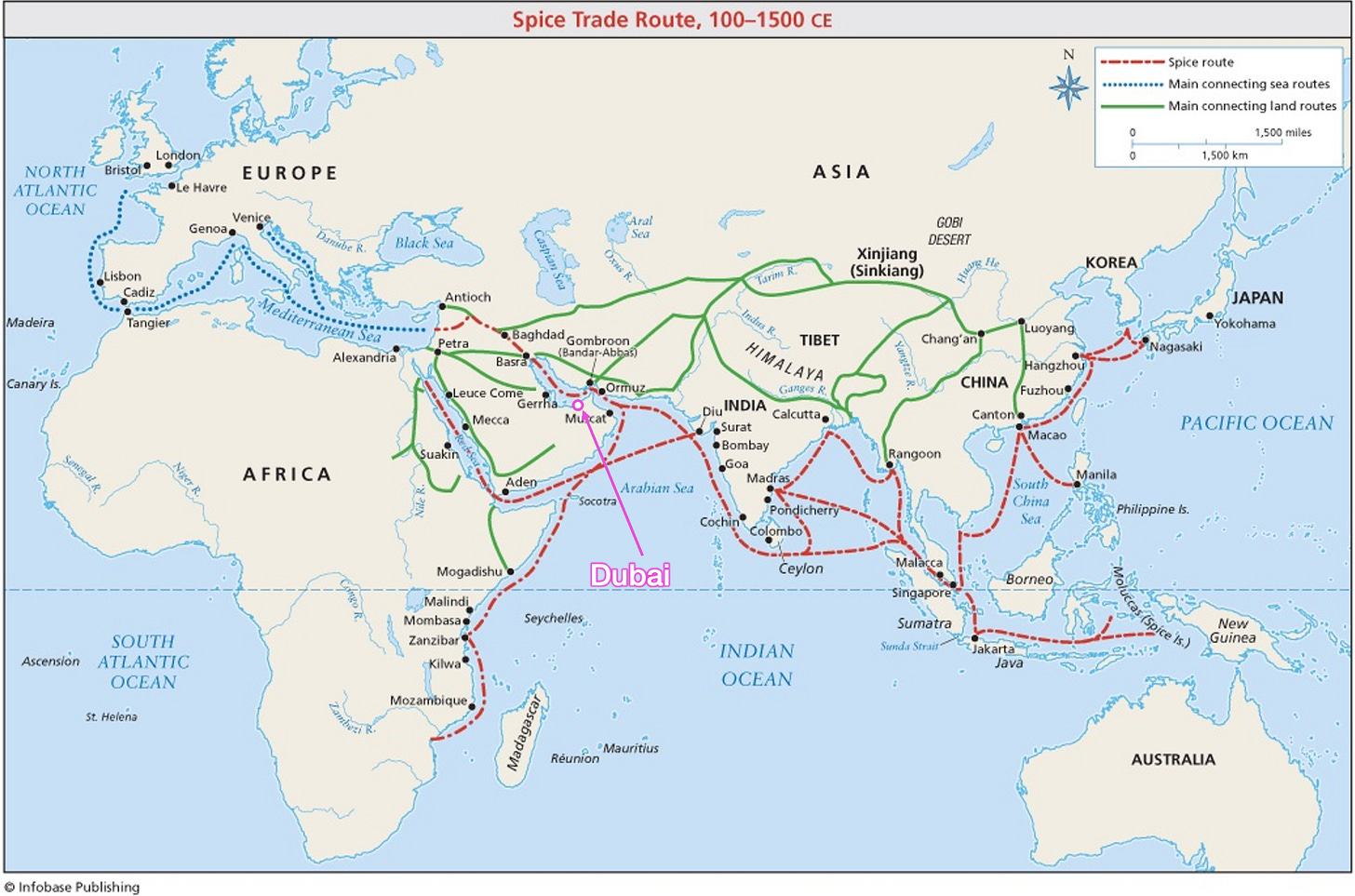

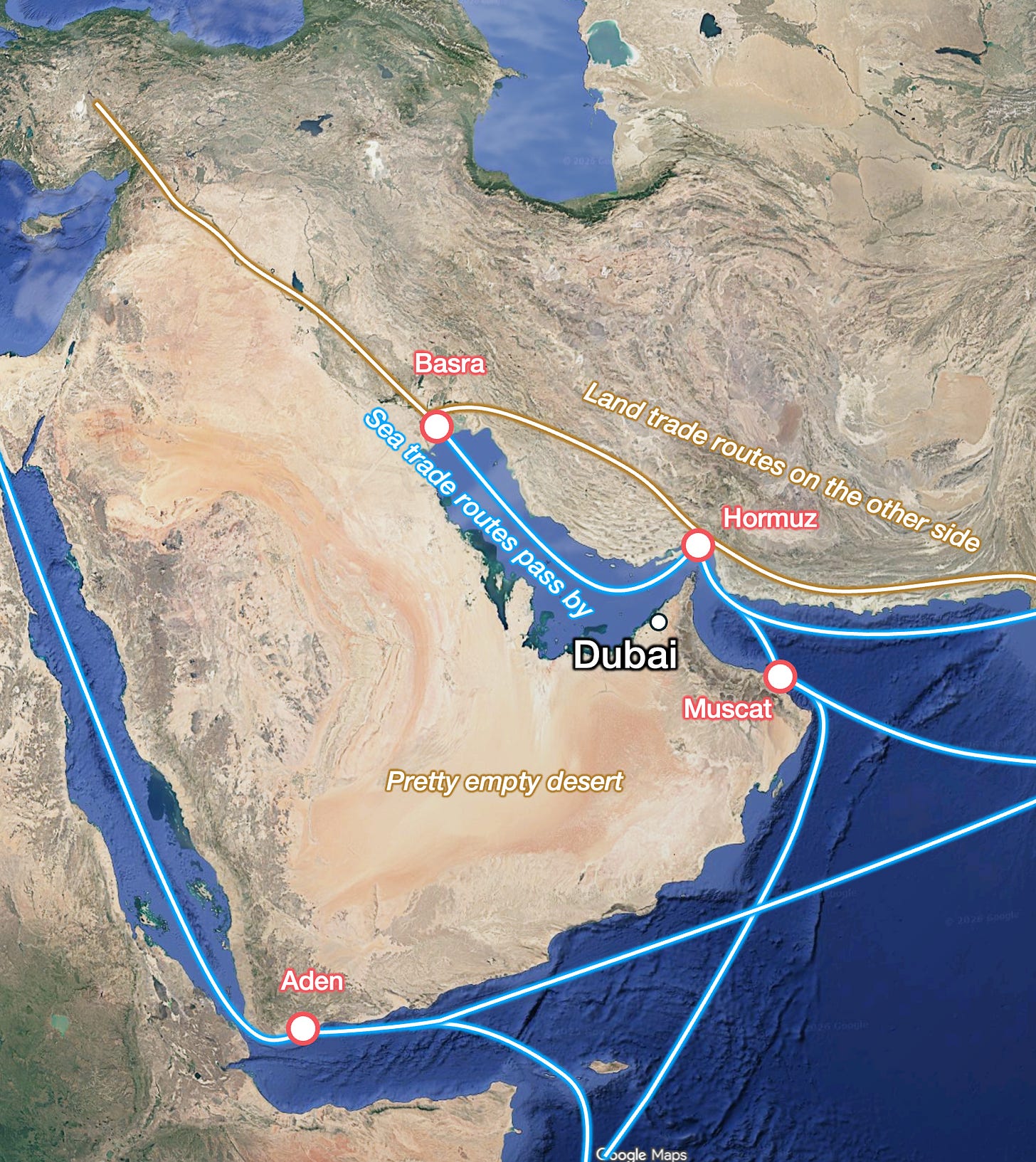

It’s on one of the most ancient trade routes.

Unfortunately, Dubai mostly saw ships pass by, as it’s on desert land, leading nowhere. It was never a crossroads for anything.

So as a result it was not even a minor trade outpost at the height of Muslim power.

That did not get better with the Age of Discovery and its more euro-centric trade routes that completely bypassed the Persian Gulf.

The region didn’t have that much going on in that period. The little trade that went on suffered from pirate raids, so Dubai built a fort in the late 1700s.

In the 1800s, the region became a British Protectorate: Too poor for the UK to turn into a full-on colony, the Brits promised to protect the region in exchange for its help fighting against piracy.

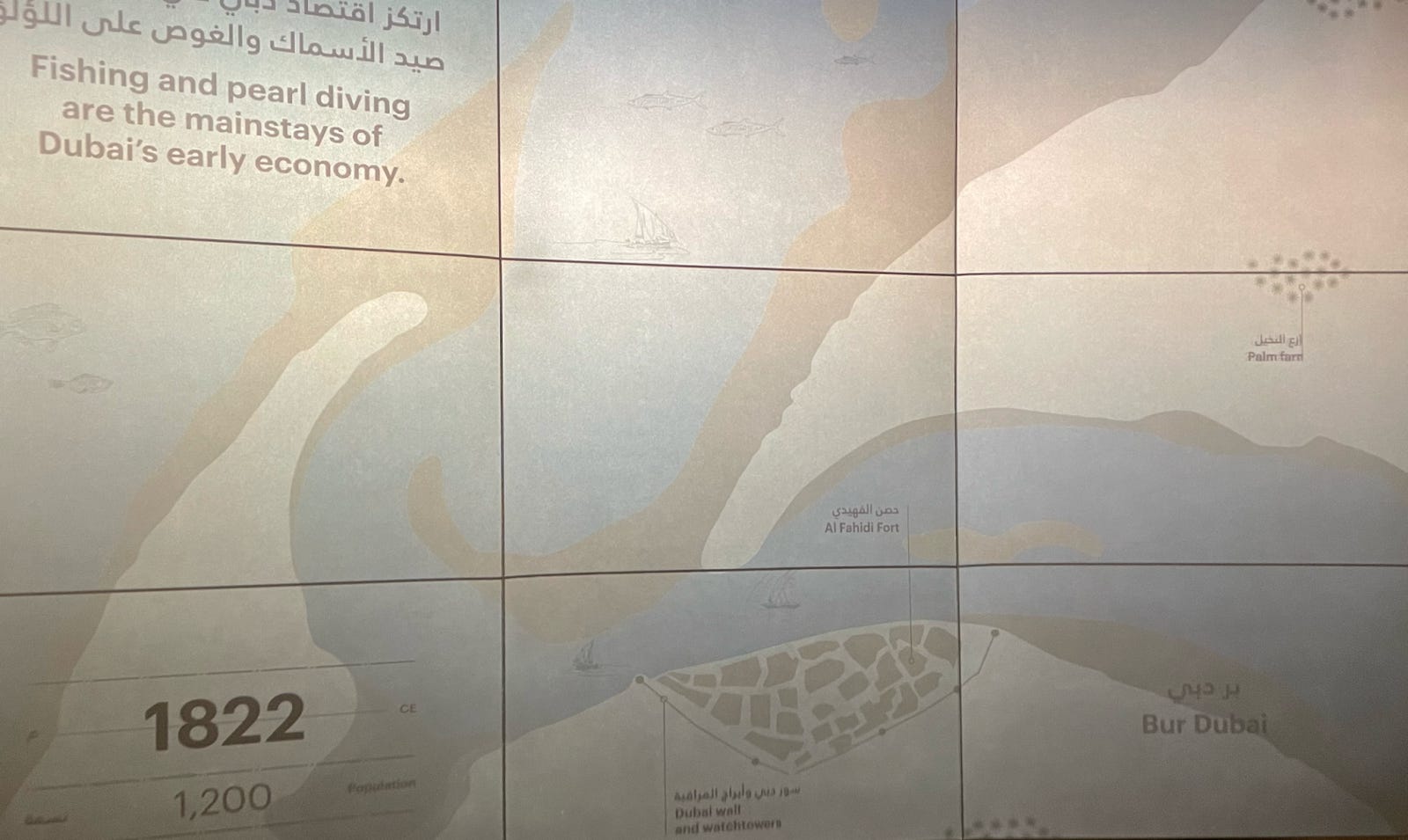

So for centuries, the only remarkable economic activity in Dubai, and the Persian Gulf in general, was the pearl industry.

Diving for Pearls

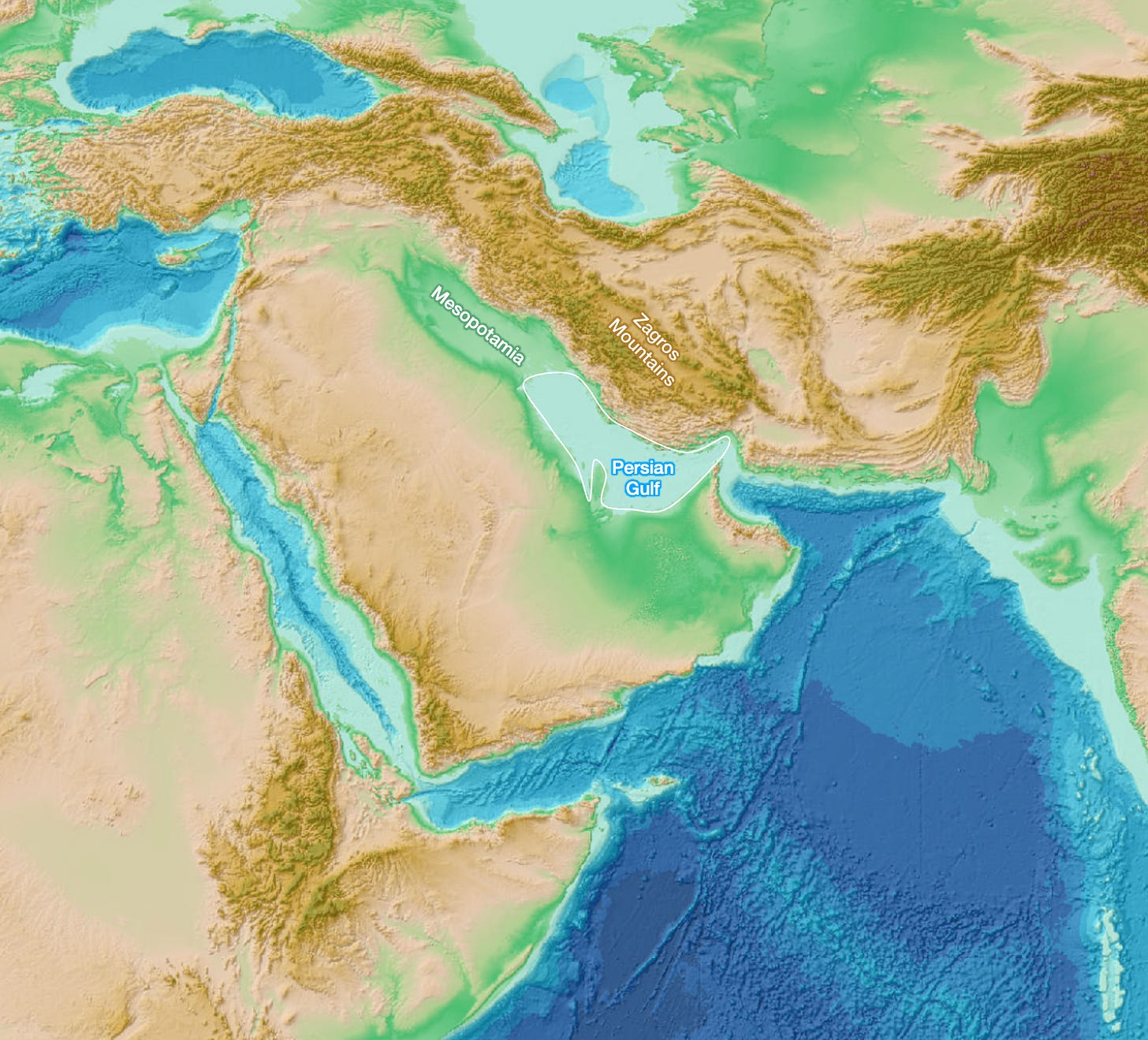

The Persian Gulf is a very shallow sea, about 35 m deep on average.1 In reality, it’s just the underwater continuation of Mesopotamia. They are both depressions caused by the weight of the Zagros Mountains to their northeast.

And this part of the world has lots of sunlight and little rainfall. This created a goldilocks environment for oysters and their pearls:

Shallow waters mean sunlight reaches the bottom, and there’s a lot of plankton that the oysters can eat.

They like warm temperatures.

No rain means few rivers, so little mud in suspension in the water to clog the oysters’ gills.

These conditions have persisted for millions of years, so the shells of trillions of animals have accumulated, forming a carbonate bed that oysters can use to build their own shells. This carbonate has not been diluted by sand from rivers, and with all this carbonate concentration, the water is alkaline, facilitating shell creation.

The warm and salty environment is ideal for parasites. They penetrate the oyster, which defends itself by surrounding the parasite with nacre, forming a pearl.2

It’s also close enough to the surface for divers to be able to reach them without any special breathing equipment.

This is why the entire Persian Gulf was the world’s biggest producer of pearls.

That industry got destroyed in the 1930s, after the Japanese had learned to cultivate pearls by artificially inserting something in the oysters’ sac, which then proceed to cover them in nacre. The Great Depression that started in 1929 finished off the industry. Only fishing was left.

So Dubai was just a fishing village well into the 1950s:

But it had one thing that made it special: its creek.

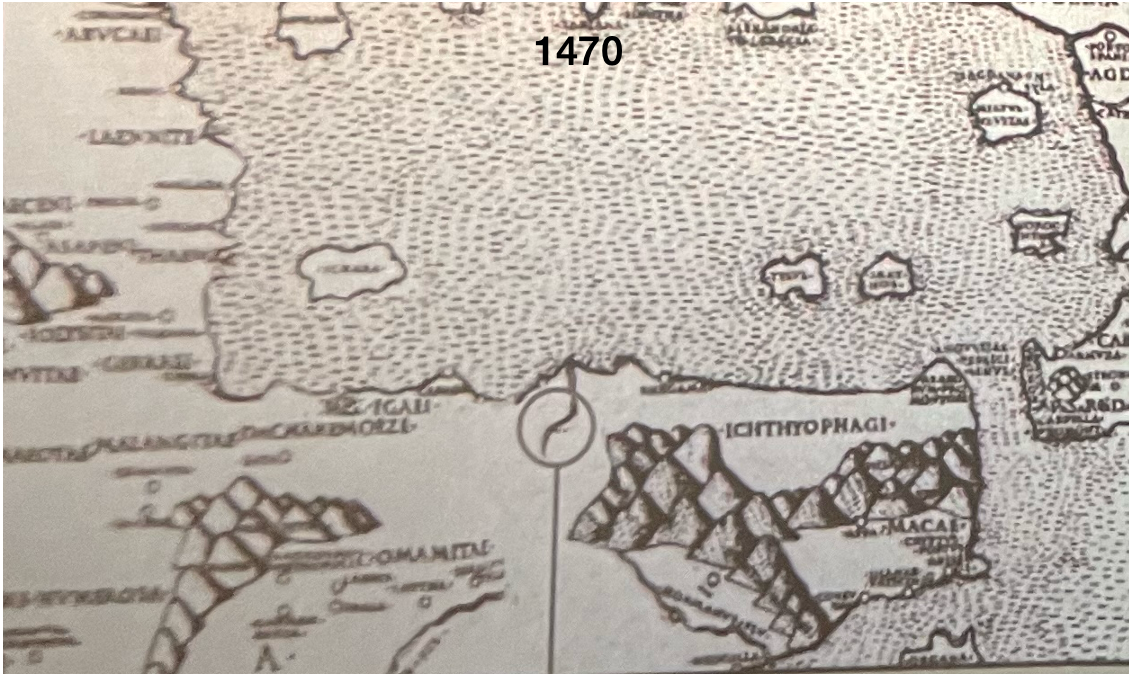

The Creek

The creek appears in ancient maps, showing how salient it was.

A creek provides protection for ships from sea storms and pirates, so Dubai could theoretically be a port. But how do you compete with all the other ports in the region, when you don’t have special goods to trade, as you’re in the middle of desert land?

Here’s the fundamental insight that Dubai’s rulers had around 1900 that made Dubai what it is today: In the modern age, you don’t need an amazing natural endowment to succeed as a city. You just need amazing governance.

The Regulatory Arbitrage

In the late 1800s, Dubai’s rulers focused on ensuring Dubai was safe. Once they succeeded, they wondered: How can we use our creek to lure merchants from neighboring cities to settle here?

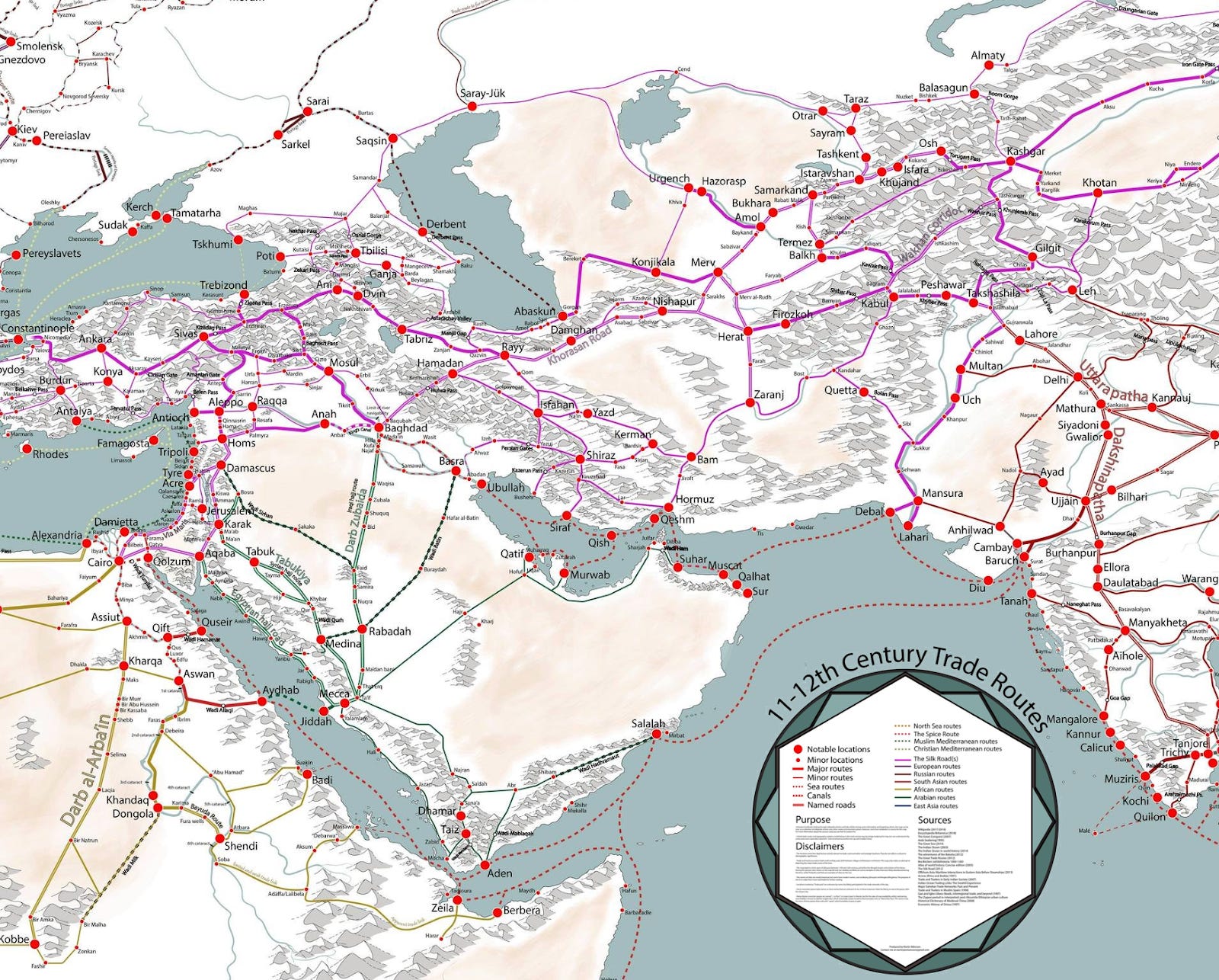

At the time, the biggest port in the gulf was Basra, in the Ottoman Empire. In the region, it was Lingeh, in Persia, on the northern coast of the Persian Gulf. Small creeks competed with Dubai for local trade.

But over the centuries, the Ottoman Empire started taxing the merchants in Basra more and more to finance its wars. This happened in Lingeh in the late 1800s, too. But there’s only so much you can tax merchants before they leave.

So in 1901-1902, the ruler of Dubai decided to make the port what we understand today as a Special Economic Zone (SEZ): Merchants were granted land on the creek, zero taxes, protection, and tolerance of their beliefs. Merchants left the surrounding regions and established themselves in Dubai. The new steamboats that were accelerating global trade began stopping in Dubai. By 1906, Dubai had replaced Lingeh as the major regional port. Here’s the same population graph as before, but this time logarithmic:

This was not a novel strategy: Many coastal cities had used similar strategies in the past, from the Phoenicians and Greeks to the Hanseatic League. Within the British Empire, this was common: Singapore (1819), Hong Kong (1842), and Aden (1839) all followed the same recipe. So Dubai knew what it was doing, and the British saw it positively, as an alternative to Persian and Ottoman trading power in the region.

Why did it work for Dubai? A big reason was that it was weak. That weakness was an asset, not a liability: The port was not huge, the Sheikh was not powerful, so if he tried anything, merchants would just pack up and go.

Instead, Dubai did whatever it could to improve the conditions for its merchants. Notably, as sandbanks had accumulated in the creek, Dubai worked with the merchants to dredge it. Dubai got the British Empire to establish a post office there in 1909—much earlier than in any other city in the vicinity—and later the telegraph.

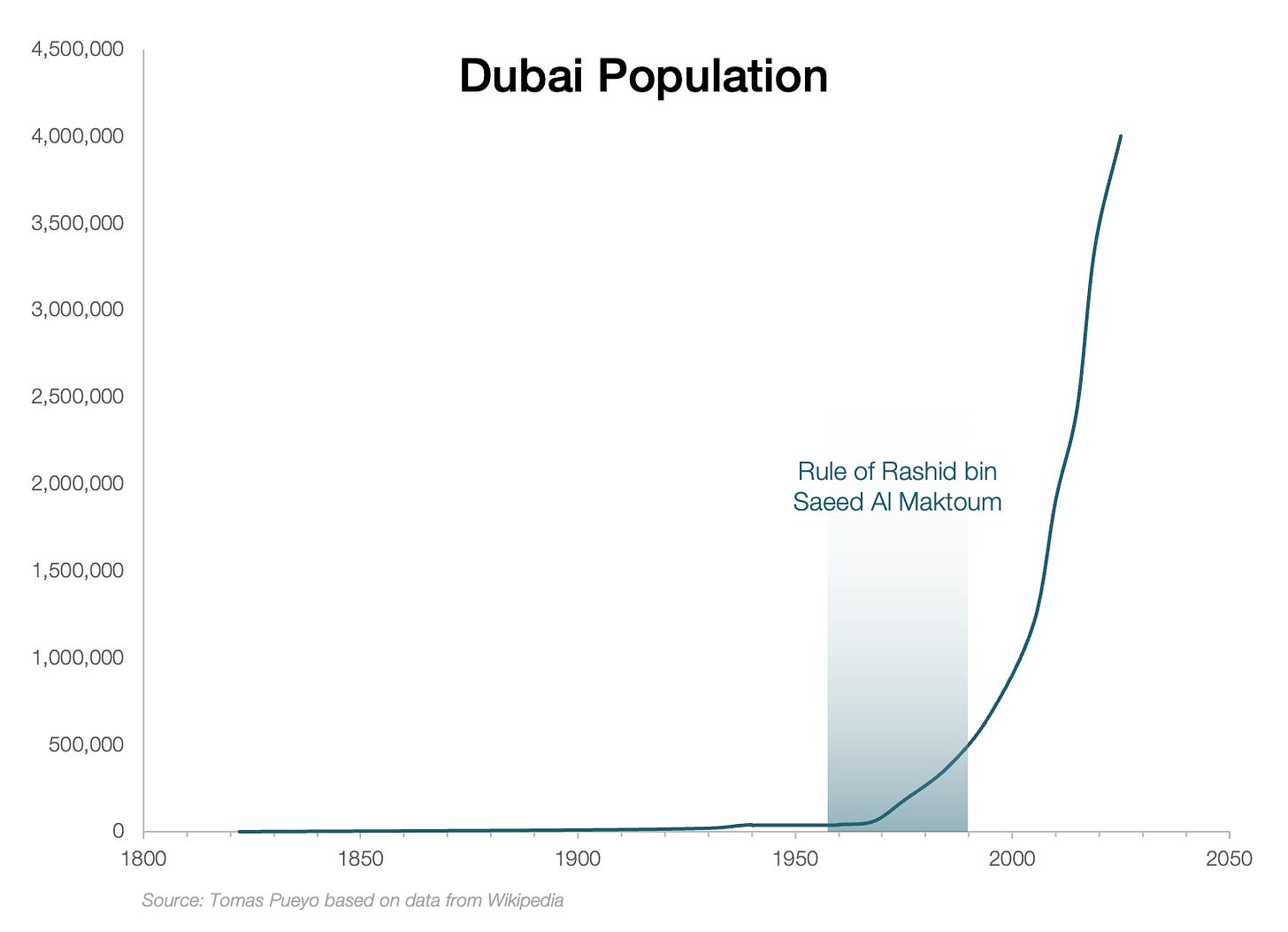

With these measures, Dubai’s population 4xed between 1900 and 1950, despite the pearl crash. But more importantly, Dubai had planted the seed of what would make it great: a commitment to low taxes, trade, safety, and tolerance.

Dubai’s Explosion

It’s now 1958, and the man from the beginning of this article, Sheikh Rashid bin Saeed Al Maktoum, succeeds his father as the ruler of Dubai.

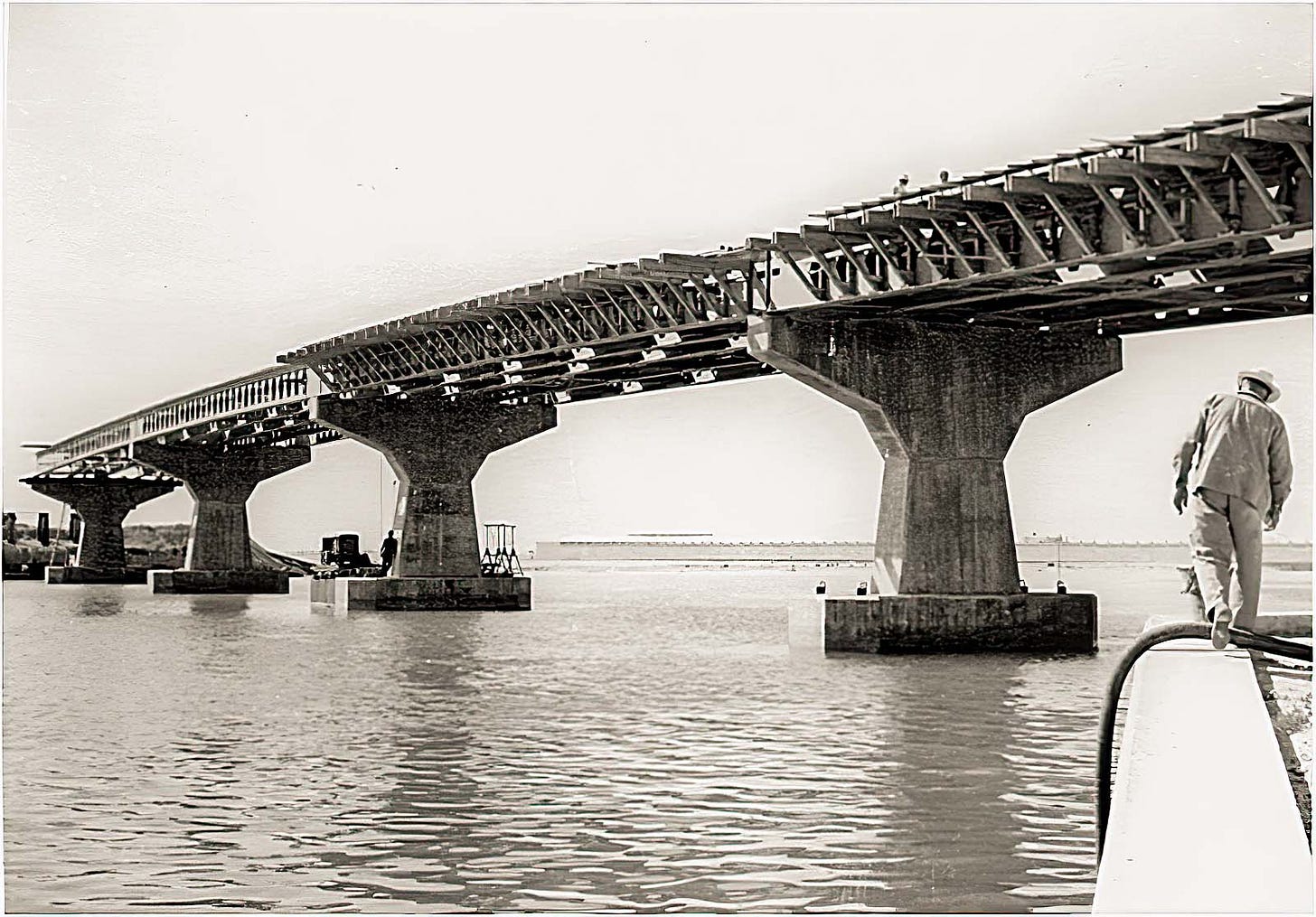

Sheikh Rashid went all in on infrastructure.

Dubai’s Infrastructure Run

This is what he did:

1959: Establish Dubai’s first telephone company

1960: The first airport opens

1961: Roll out the electricity network

Late 1950s, early 1960s: Dredging Dubai Creek, after which vessels of any size could dock at the port.

1963: First bridge over the Creek

All of these required a strong vision—and immense investment risk in the case of the dredging, the bridge, and the airport—because Dubai only discovered oil in 1966, and production started in 1969!

Dubai’s Flare

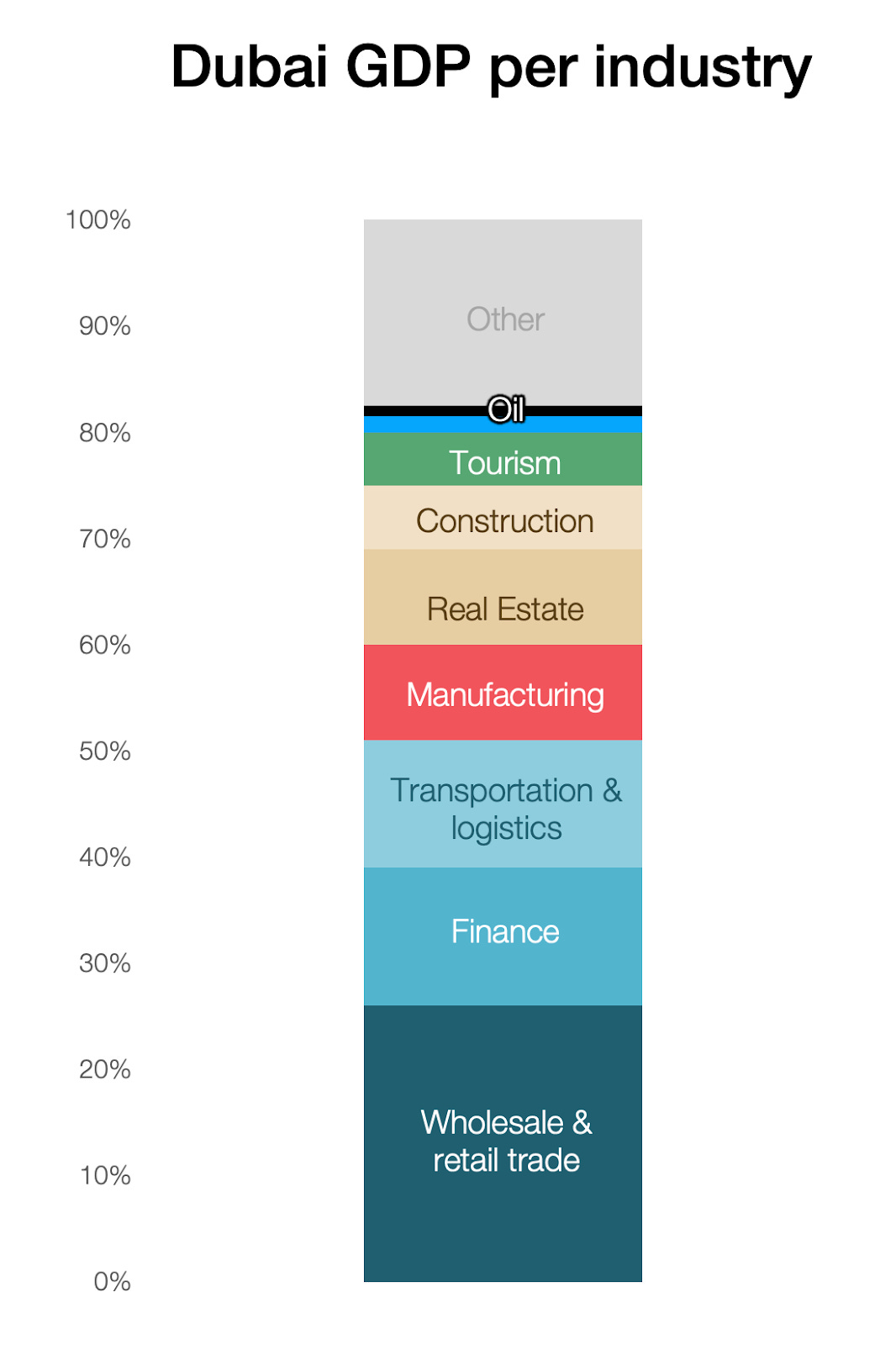

The oil was an incredible boon for the economy, but the Sheikh knew it wouldn’t last. He was right.

So, starting in the 1970s, Dubai’s challenge was: How can we use the windfall to create an economy that will sustain itself when there’s no more oil?

Very few countries think this way today, forget about the 1970s.

But Dubai had the answer. Dubai Creek was already the biggest import-export port in the Persian Gulf in 1960, if you extract oil cargo.3 So Dubai decided to double down on its strength: trade.

It used oil money to built Port Rashid, which opened in 1972, because Dubai Creek silted and had become too small.

1975: Al Shindagha Tunnel opens under Dubai Creek, closer to the entrance of the creek.

1979: Dubai opens its World Trade Centre, a convention and exhibition center.

1979: Aluminium production starts: This was very clever, as it moved the city from just a trading hub to one that could add value to the goods before reselling them, and generated both jobs and industry in the process.

1979: A new port opens south in Jebel Ali! This would become Dubai’s biggest port, and the largest one in the entire Middle East to this day.

1983: Drydocks open near Port Rashid to repair ships.

1985: Jebel Ali, to the south, becomes another free trade zone to expand the congested Port Rashid.

Dubai’s Diversification

As oil dwindled, trade had already firmly established itself, so Dubai could continue its aggressive diversification across adjacent industries: finance, tourism, real estate…

Since the turn of the century, the city has gone all-in on urban development.

You can see this development not just in skyscrapers, but in retail, real estate and tourism, with famous landmarks like the Burj Al Arab hotel:

Dubai has the tallest building in the world, the Burh Khalifa.

It’s in front of the 2nd biggest mall in the world, Dubai Mall.4

It has reclaimed land on the coast to create Palm Jumeirah:

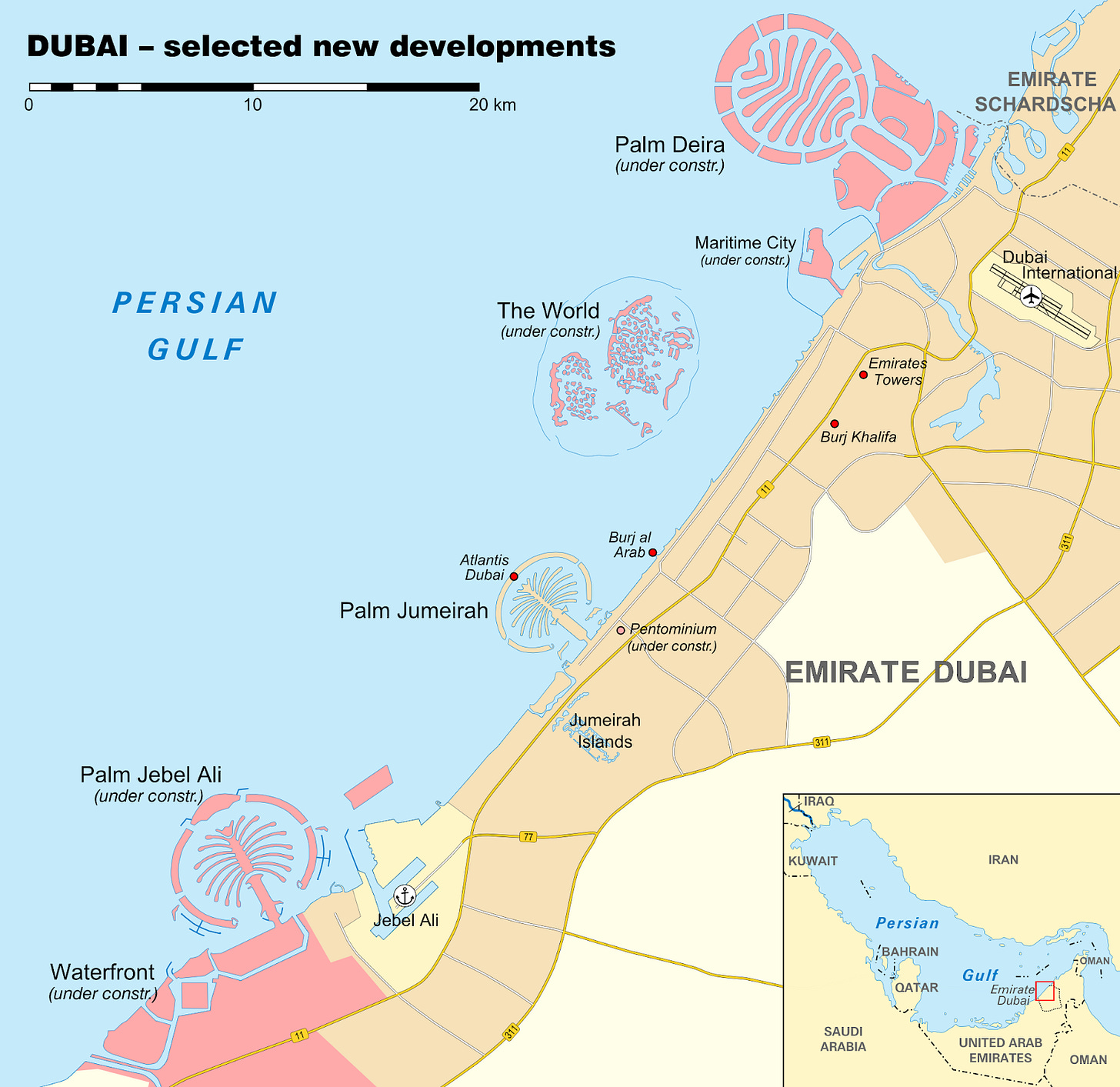

Several other coastal reclamation projects have begun, such as Palm Jebel Ali, The World Islands, and Dubai Islands, but none are complete yet.

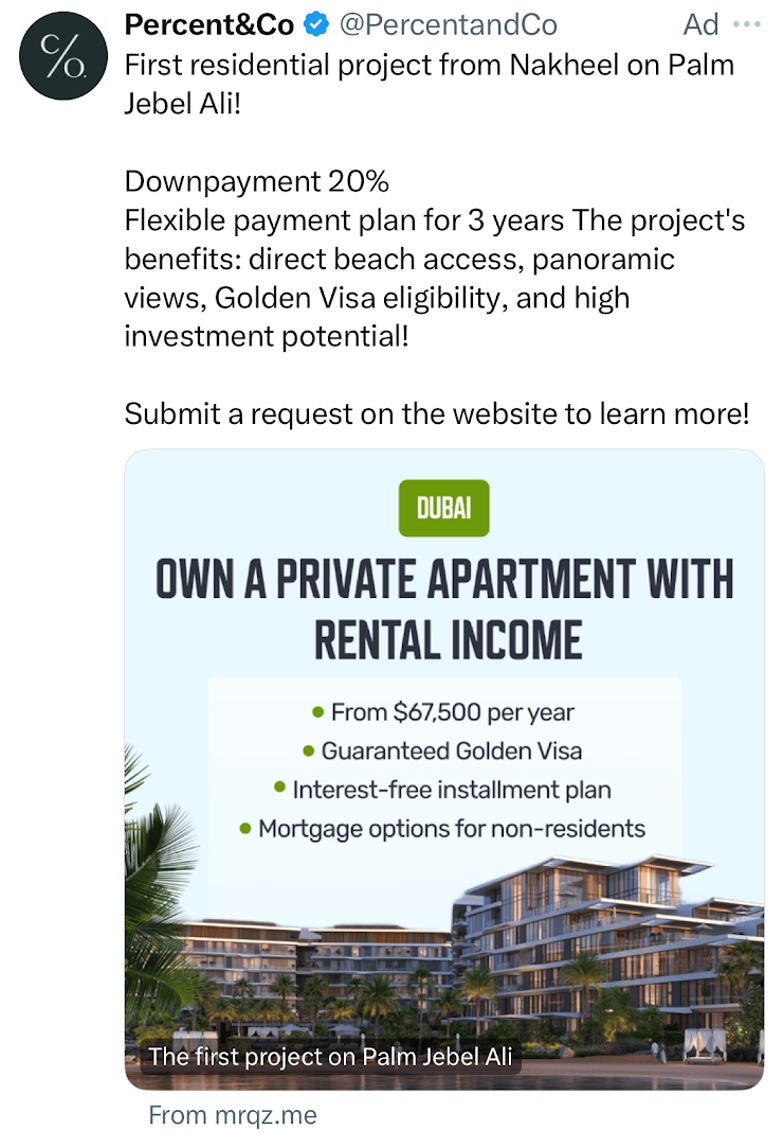

Many of them commenced construction just before 2008 and stopped during the Great Recession. Most haven’t started redeveloping again,5 although an ad tells me they’re trying with Jebel Ali.

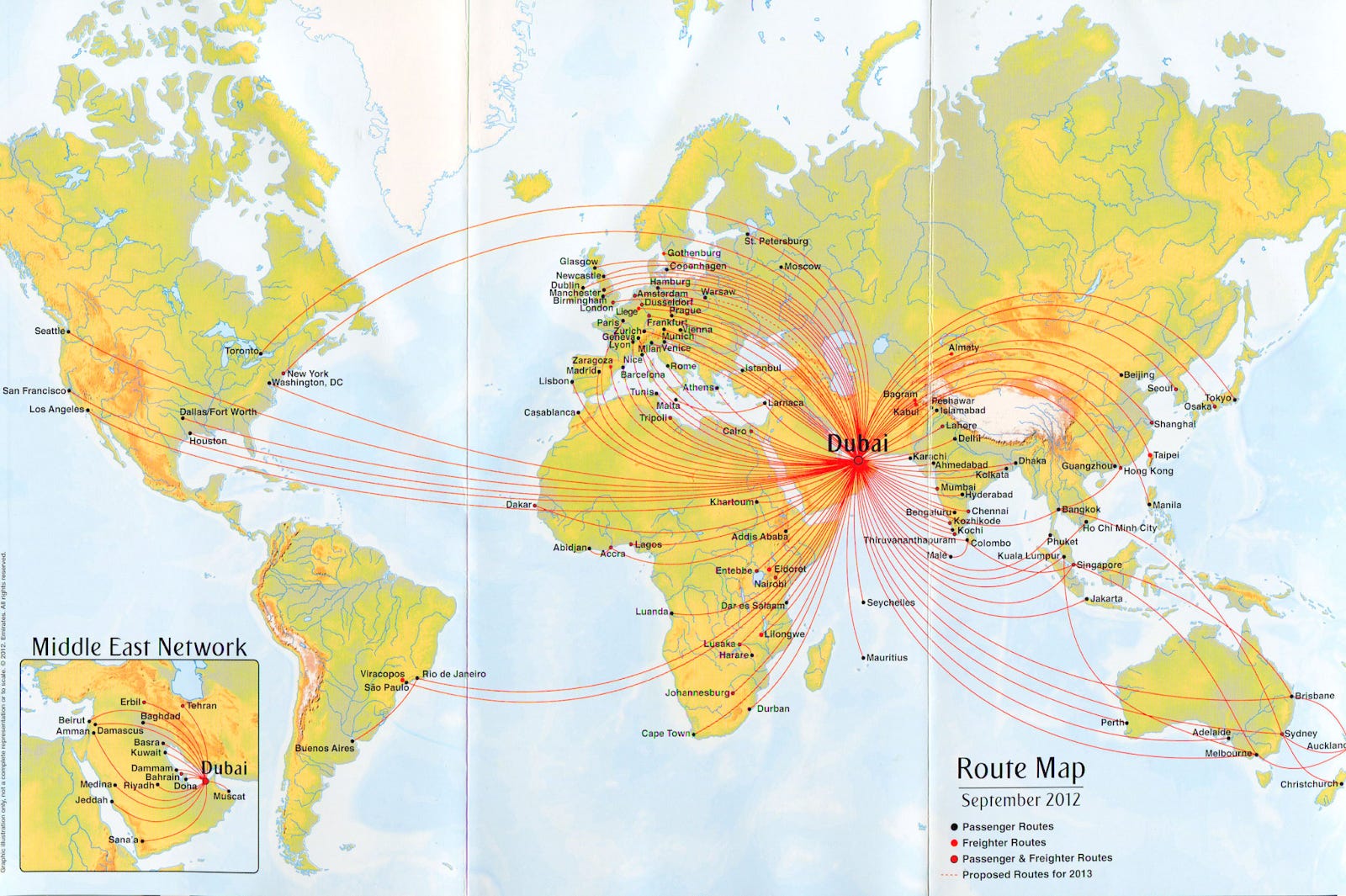

Dubai understood that there are huge synergies between transportation modes, so it didn’t only invest in its port and coast. It continued investing in its airport and airline. Today, Dubai International Airport is the 2nd busiest in the world, and the Dubai-based Emirates Airline is the world’s largest long haul airline. It acts as the bridge across Europe, Asia, and Africa.

Dubai’s Differentiation

But Dubai was not built only on physical investments. Since its beginnings in the early 1900s, its leaders knew that to attract people you needed the right regulations:

Very low taxes

Safety

Tolerance

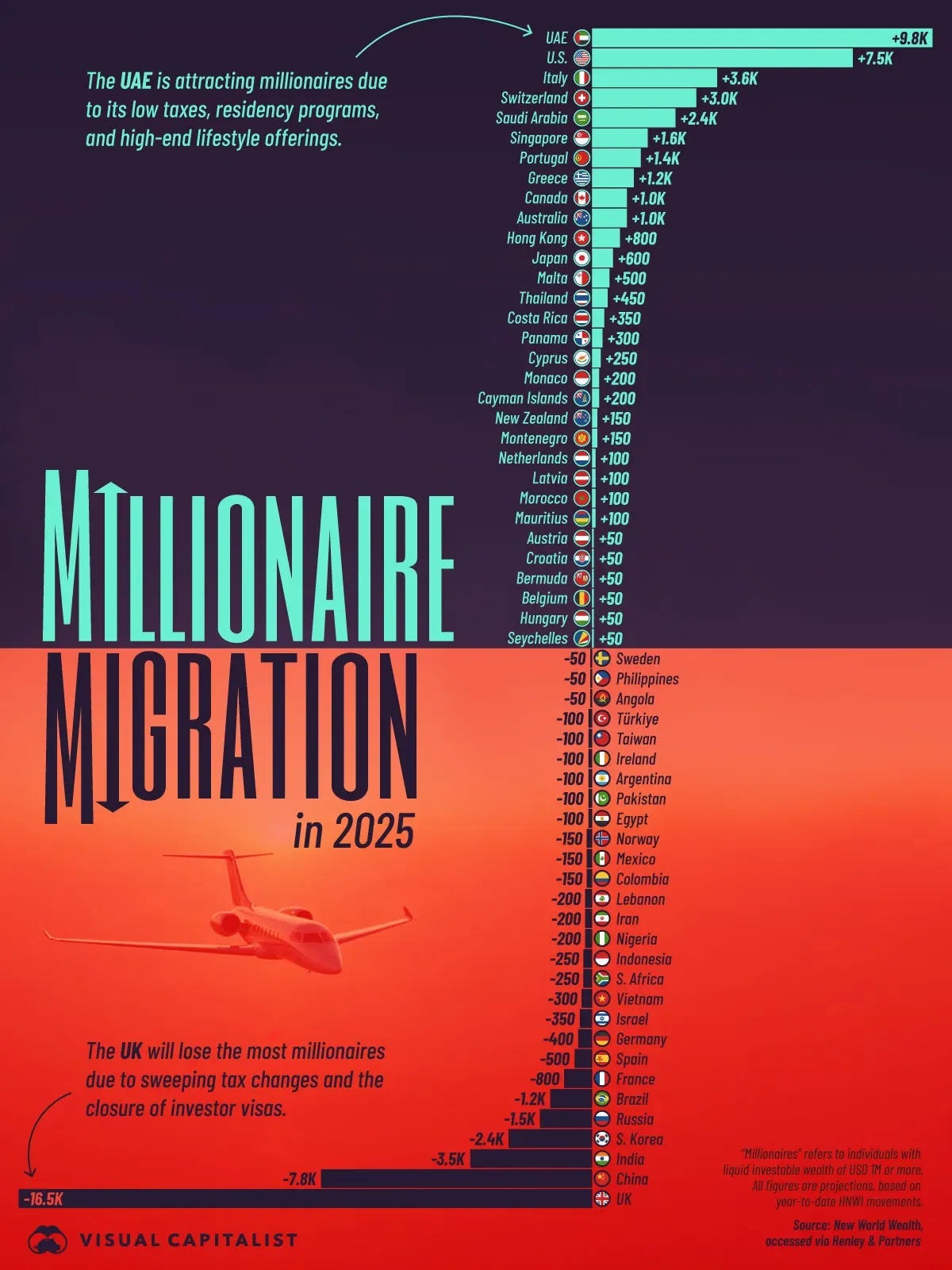

Dubai is the 2nd most tax-friendly city in the world. No wonder it’s attracting huge numbers of millionaires escaping high taxation around the world. Here, Dubai appears as part of the United Arab Emirates:

Dubai is also the 5th safest city in the world. When I was there, all the locals and expats I talked with had stories about how they left a computer behind and the police tracked it back to them within a couple of hours, how they can leave their cars open and running without fear of theft, or how their children can take the local Uber equivalent (Careem) alone. When I was there, I felt as safe as in Taipei, Tokyo, or Singapore, and way safer than anywhere in the US, or in most European cities.

Finally, as a Muslim monarchy, the UAE is not known for freedom. Criticism of rulers, state institutions, religion, or “social harmony” can lead to detention. Online speech, including social media posts, is closely monitored. Media outlets are state-owned or closely aligned with authorities. Public demonstrations require permission and are rarely allowed. Independent civil society organizations are limited; strikes are illegal in many sectors. Public morality laws affect dress, alcohol, relationships.

That said, I don’t find any of these fundamentally different from those of, say, Singapore. They only differ in degree. And in practice, in Dubai I saw plenty of drunk expats and scantily dressed women. In Singapore as in Dubai, it felt like people say: Live and let live. Do your thing in private, leave others alone, and we’ll leave you alone.

This felt liberating. Knowing you can go anywhere, at any time, do your thing, be respectful, and you’ll be free? That’s amazing. When I lived in San Francisco, I had to be aware of my surroundings when walking on the streets, for fear of attacks. And my speech was not much more free in SF, as I always had to be very conscious of what I said and how it would land with people, for fear of making a faux pas or hurting sensitivities.

That’s the difference between freedom and tolerance. If I had to choose only one for the rest of my life and the entire world, I would choose the freedom of the US. But to live in a city that you can leave at any time, the tolerance of a place like Dubai, with the safety that comes with it, is much more comfortable.

Dubai Tomorrow

So this is how Dubai went from a village of fishermen and pearl divers to one of the world’s most dynamic metropoles: It tried to become the biggest trading hub it could. For that, it focused on two things:

The right infrastructure for transportation and communication: ports, postal services, telegraph, bridges, tunnels, airports, malls, artificial islands…

The right regulations: low taxes, security, and tolerance.

This is how it became a trade hub, and as we’ve seen in previous articles, once cities become hubs, network effects are so strong that they keep growing.6

Today, Dubai still makes $500M in oil revenue per year, but that’s less than 1% of the city’s GDP. Given its unbelievable position for trade and transportation, and all the services burgeoning around it, it seems to me like it’s well positioned for the future.

The same can’t be said of Abu Dhabi, the biggest emirate in the United Arab Emirates, which still prints money from oil sales. If Abu Dhabi can’t manage the transition away from oil, will it carry Dubai down with it?

What Lessons Can We Take from Dubai?

1. Modern Islam

While Western media is filled with stories of intolerant, aggressive, backward-looking Islam, Dubai shows that this narrative doesn’t need to prevail. A Muslim monarchy can be tolerant, welcoming, rich, dynamic, and cosmopolitan.

2. Living after Oil

When I first heard the story of Dubai, I thought it was a role model for other oil countries to transition out of their oil dependence, but now I’m not so sure: Dubai did not go from oil city to trading city. It was always a trading city, and oil just helped it reach its ambitions. Crucially, this means it avoided the resource curse because its institutions and culture were so strong to begin with.7 Oil did not make Dubai. It just helped.

3. Global Competition

The world is hyper competitive. You never control your population. People are always trying to go to the next best place. So governments can’t act as if their population is a hostage to milk. The countries that treat their populations (and immigrants) well, with low taxes, tolerance, and security, will attract money and power and outgrow the others.

Approximately the same in yards. The sea is frequently less than 10 – 15 m deep.

Also, the high salinity, extreme summer heat, rapid temperature swings in shallow water, and periodic lack of oxygen create stress that weakens the oysters’ shells, which facilitates parasite penetration.

Other ports were focused on the transition of bulk goods inland, not as entrepots. Persia and Iraq were too controlling of their ports for them to flourish, while Dubai had been a SEZ for decades.

By surface

A big chunk of the World Islands were sold, so the incentive for further investing isn’t there, yet many of the acquirers did it for speculation, so the project is stalled. Plus, the cost of connecting all these islands with roads, electricity, and water are pretty high. My guess is Palm Jebel Ali or Dubai Islands will finish before The World.

As long as they’re not throttled by some force, usually regulation.

It looks like it was mostly the rulers: Dubai’s Al Maktoum family has shepherded the emirate for over two centuries of modernization pretty impressively.

Well done, Tomas. It's rare to see such a nuanced article about Dubai, especially from someone who hasn't lived there.

You've perfectly understood Dubai's (very clever) positioning in this new world.

May I suggest my article "Why I Feel Freer in a Monarchy Than in My Democratic Home Country -

Reflections on Dubai and the freedom granted by digital nomadism" https://disruptive-horizons.com/p/why-i-feel-freer-in-a-monarchy as a supplement? I lived in Dubai for seven years and know the city very well.

Also, to summarize one of my points about what gives Dubai such a feeling of freedom:

"For several years, I haven’t needed to show a passport at Dubai airport: facial recognition identifies me and the gate opens automatically. It’s efficient—but it also shows how easily governments can track people. In Dubai, cameras are everywhere and actively used by police; finding a stolen car is trivial. If you can track cars, you can track individuals.

The UAE clearly offers fewer political freedoms than Western democracies, so yes—mass surveillance bothers me. But, paradoxically, less than it would in my home country.

Why? Two reasons. First, the balance of power is different. There’s a distinct implicit contract between someone born into a country and someone who chooses a country in a competitive market of jurisdictions. The mono-country person is constrained by inertia—language, ties, habits—and feels the state’s weight acutely. The nomad arrives as a customer. If the value deteriorates or surveillance becomes too heavy, he can—and should—leave.

That possibility fundamentally rebalances power. I can choose where to live and contribute, and states must compete to keep me. So I know that if Dubai no longer suits me, I’ll leave. Accepting slightly more state power is the trade-off for having strong exit power. In practice, voting with your feet balances power better than voting at the ballot box—an essential insight when choosing your first expatriate country."

(I share the 2nd reason in the above article)

So we agree on this point.

I normally love your analyses, but this one made me physically ill.

Dubai is built on modern slavery. Exploitation and extraction levied against foreign workers with virtually no rights to begin with, and no ability to assert them.

Dubai, like Singapore, is simply a modern conservative society - law enforcing a social order.

That is why millionaires like it.

For shame.