Infinite Intelligence Solves Most Problems

Most misery comes from scarcity.

Intelligence will eliminate most scarcity.

What do humans need? Let’s start with the bottom of Maslow’s pyramid, with things like food, water, shelter, clothing, safety, or health.

The Source of Everything

Why Does Food Cost Money?

You want lots of quality, diverse food. Why are there people who can’t afford it? Even if you can afford it, you have to spend money on it that you can’t then spend on other things. You’re making a sacrifice to get that food, unlike for example the air you breathe. Why? It’s the result of scarcity. And where does this scarcity come from?

To get food, we first need land. Land is scarce.

It’s also not perfectly fertile, so we need to use fertilizer. Fertilizer is expensive, because it’s scarce. Why is it scarce?

Fertilizer is mainly made of nitrogen, phosphorus, and potassium.

Nitrogen is usually fixed through ammonia, NH3, which can be obtained from the air’s nitrogen and water through the Haber-Bosch process, which requires energy. Energy is scarce.

The best way we can get phosphorus today is by mining it from phosphate rocks, which are later treated with chemicals. 70% of known phosphate rocks are in Morocco. They are not renewable and are scarce.

Potassium comes from potassium salts, which are reasonably abundant. They still need to be mined, which means human work and energy, which are scarce.

Once these elements are gathered, they need to be mixed into fertilizer, transported to the fields, planted, taken care of, harvested, treated, transported to the market, and sold.

Each one of these steps requires energy, human work, and machinery.

But transport is just workers, machinery, and energy.

Machinery, in turn, is just energy, raw materials, land, and human work.

How to Make a Machine

Let’s take a truck, for example. It’s made of parts that are later transported to an assembly plant. After the assembly, the finished truck is transported to a warehouse maybe, until it’s sent to the place where it’s sold. All of these steps require yet more machinery, energy, land, and human work.

Where do the parts come from? Usually, they are made up of smaller parts that are also transformed and assembled in the same way.

If you continue going upstream, you end up with raw iron, raw steel, raw oil, raw leather… Each of these inputs in turn comes from raw materials:

Iron and steel come from mined iron ore, energy, and some source of carbon.

Oil is just a raw material pumped from the Earth.

True leather comes from farming, which is similar to the process we covered for food.

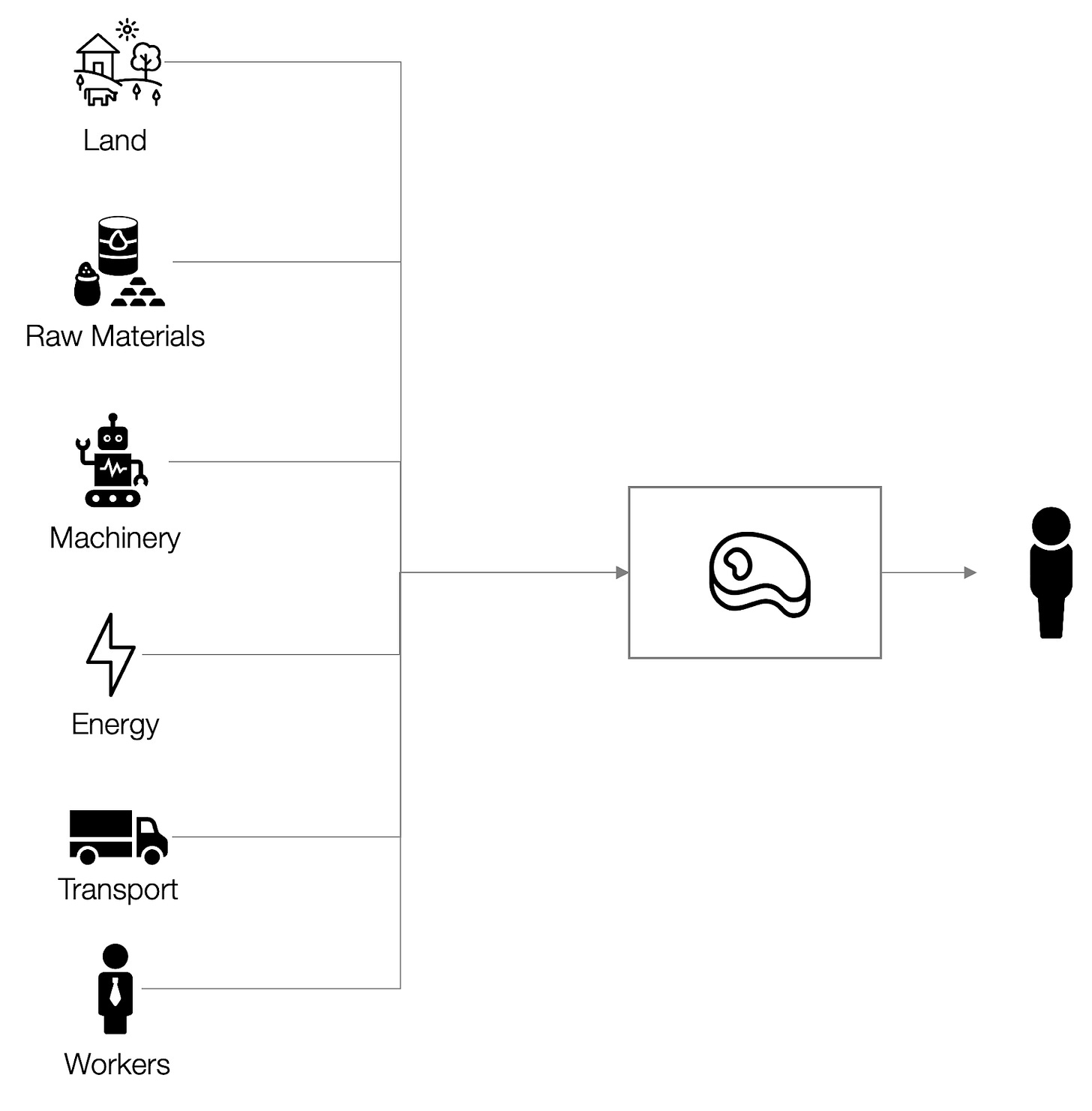

If you summarize all of this, when you go all the way upstream, all the food we make uses four scarce things:

Land

Raw materials

Energy

Human work

Note that when something is not scarce, it doesn’t cost money, even if we use it. For example, nitrogen is used for fertilizer, but since it can be sourced from the air, it doesn’t cost anything.

Why Does Water Cost Money?

In most developed places, it doesn’t cost much, because it can be obtained from local freshwater sources like rivers and streams. In those situations, the cost of water is mostly the cost of the infrastructure to source it, its maintenance, and the treatment of water. Sometimes these sources are very far away, which requires more resources, but they still boil down to raw materials, energy, land, and human work.

When water is not as available, it needs to be sourced from the air or the sea. Both of these are possible, but they take human work, land, raw materials, and a lot of energy. The same four scarce ingredients.

What About Other Goods and Services?

For shelter, you need land and a shelter on top of it. For the shelter, you need raw materials and human work. Sometimes, you need to respect construction legislation, which is an artificial form of scarcity, linked to the fact that some land is more valuable than others, so communities impose a premium on it.

Why do people want to live in some places more than others? One of the main reasons is access to quality of life, which can come from the availability of services like educators, police, supermarkets, stores, cinemas… All of these are the result of land, raw materials, and human work, which are scarce.

They might also want to be close to other valuable humans, such as their family, friends, interesting people, potential mates… Other humans are scarce. You can’t buy access to them directly, but you can buy it indirectly by paying to live close to them.

What about things like clothing, safety, financial services, education, or health? They all boil down to the same elements: mostly raw materials, land, energy, and human work.

That’s the economy: a series of processes that mostly convert land, raw materials, energy, and human work into everything we buy.

Does this mean these are the immutable elements of scarcity? No.

Scarcity Is Mutable

The Evolution of Energy

Light used to be extremely expensive.

Today, it takes less than one second of human work to afford an hour of lighting. In 1800, it took 5 hours of work. 4,000 years ago, it took over two days of work.

Why? What happened? A couple of things. First, our lighting is much more efficient.

We improved our technology to use less energy for every unit of light we produce. Through human work, we’ve inserted human intelligence to make things better and better over time.

We’ve done the same thing with energy. Thousands of years ago, all our energy came from our food, converted into human muscle, or from wood we burned. We learned to use animals to help us, to harness the force of rivers or wind for mills, we learned to convert heat into power with the steam engine, the chemical energy from oil into power through the combustion engine, power into electricity through generators… All this is the history of humans working to insert their intelligence into improving productivity.

Every year, we extract more energy from the Sun more cheaply.

We’re inserting intelligence to make energy less and less scarce. Project this into the future, through solar or maybe fusion, and energy might stop being scarce at all. It might become like water in developed countries, something we might spend some money on, but we barely notice.

Put in another way, in the future, one of the scarcities will disappear, and we will only have land, raw materials, and human work left as scarcity.

But the scarcity of raw materials can also disappear.

The Evolution of Raw Materials

When Aluminium was discovered, it was so scarce and light that royalty used it to replace their silverware. Then, it became extremely easy to extract, and it became a common element. Royalty went back to silverware.

This has been true of most raw materials in the world. They were too hard to find, until we inserted intelligence in the process and found them. This is why peak oil has been declared for decades, but in fact we might well find peak oil not because we can’t find it anymore, but because we don’t need it anymore.

But better mining can’t solve all raw material scarcities. What about rare elements? There’s only so much gold, so much uranium, so much neodymium on Earth. Surely this is a hard limit to raw materials?

Transmutation! We can change elements into other elements. That’s what nuclear fission is, and what nuclear fusion is trying to achieve. The issue is that it takes too much energy, so we don’t even contemplate it. But if energy costs nothing, we will be able to do it, at which point we’ll start figuring out cheaper and cheaper ways to transmute some elements into others.

We’re left with human work and land.

The Evolution of Land

During the Roman Empire times, northern Europe was not very populated. Today, it hosts the lion’s share of Europeans. Some of the main culprits of this change were technological inventions around 1000 AC: the heavy plow, the horse collar, and the horseshoe.

In other words, technology allowed land that was previously hostile to suddenly thrive. In the future, we will not even need much land at all for food. Indoor farms can be built vertically, lit with fusion energy, every element perfectly controlled for optimal output.

But land is not just about food. Land also found other uses thanks to technology. For example, air conditioning. The American south grew much faster than the Northeast and Midwest as Americans bought their air conditioning en masse across the US between the 1950s and 1980s.

Today it’s not viable to live in Antarctica or underwater, but the only thing that prevents us from doing it is energy, raw materials, and intelligence.

In a few decades or centuries, we might be able to terraform Mars or Venus. Likewise, the only barrier that prevents us from doing it is intelligence. Today, land is scarce. But once we know how to convert any planet into a second Earth, or even to create new planets or other valuable human habitats, land won’t be as scarce.

You might look at the previous sentence and think: Come on, it will take forever for intelligence to figure out how to eliminate the scarcity of land. We can answer that by diving into the last piece, human work.

The Evolution of Human Work

So far, I’ve kept the definition of human work pretty broad. What does it mean, really?

Human work is just intelligence.

Long gone are the days when human work was just muscle. Over time, we’ve automated most of the jobs that could be automated with standard machines and computers. The ones left require too much human intelligence to automate. Even when they look simple, like driving, ironing clothes, or sewing, they’re impossible to turn into code. They require a level of intelligence that we haven’t been able to code yet.

Our intelligence has been able to eliminate the scarcity of some human work, energy, raw materials, and land. The only reason why we haven’t been able to eliminate all these scarcities is because of the fundamental scarcity: intelligence. With more of it, we could have eliminated all the other scarcities.

We will.

The Ultimate Scarcity Is Intelligence

We call the singularity the time when an AI will be so good that it will be able to optimize itself without humans. As a computer, it will do it fast. The more it improves itself, the faster it will further improve itself. Eventually, it will reach a level of intelligence that is beyond anything we imagine.

If we survive that time, it will be the end of scarcity. It will be a world without limits of energy, food, shelter, healthcare, travel, land, raw materials… Most wars and conflicts are rooted in scarcity. Without scarcity, these will end too.

People talk about a “post-scarcity” world, but they use it figuratively: a world where we can eat anything we want, but where we’re still fighting for things like the environment or shelter. I use it in a more literal way: the post-scarcity world is one where nearly all physical scarcity has ended. And more.

The Ultimate Scarcity Is Life

Humans live on average about 80 years, 120 years tops. We don’t realize how much we limit ourselves because of that.

Why do most people stick to just one career? Because life is short and starting over is seldom economically worthwhile. But would we want to work on only one thing all our life? Certainly not.

Why do most people only have one family? Because by the time the kids are grown up, we’re kinda old. Starting over looks like so much time and energy, but we don’t have much left! As a result, many people stay with partners they don’t enjoy anymore. Would they seek new adventure and form new families with infinite time? Some wouldn’t. Many certainly would.

Why do people take few risks? Because we only have one life. Risking it all for some thrills, some risk, is too dangerous. So we don’t do things we would like to do. But what if we could back ourselves up? Like in videogames, we would try things we don’t date to try. It would give us millions of experiences formerly out of reach, from bungee jumping to going to Mars.

A lot of what’s out of reach in life is simply because life is too short. Eliminate this ultimate scarcity, and we can unleash our true potential.

If AI keeps advancing at the current speed, we might experience that world.

People worry that humans won’t have a role in that world. To explore this idea, we need to visit other types of scarcities, those of a higher hierarchy in Maslow’s Pyramid: love, intimacy, family, respect, status, recognition, freedom… What do these things look like in a world of physical abundance? Will AIs replace us so thoroughly that we won’t feel the need to interact with other humans? Will we stop trying to fit in or stand out? Chasing sex with other humans? Finding human partners? Forming human families? I’ll explore this in the premium next article.

This post makes me feel a bit nervous about what kind of behavior might stem from holding these mindsets around abundance and scarcity - especially if the gist of this is misguided (in practice). I'm interested to read the next post.

I think some of the conclusions around energy are missing some super important context that may lead to opposite conclusions. I think Nate Hagens is someone who describes this perspective quite well. A couple points that feel relevant: Much of the trend of energy getting cheaper is that we were historically getting better at extracting fossil fuels, especially when we use fossil fuels to get more fossil fuels. We're seeing diminishing returns, and the 'abundantly cheap' energy we see now is an anomaly as we draw down resources which took millennia of sunlight to accrue. A second point is around renewable energy - the challenge comes with storing energy efficiently. With current battery technology, it doesn't seem like there are enough rare earth metals to make this a viable solution for large scale implementation with our current energy usage habits (Peter Zaihan makes this case well).

In my part of the network, we come from an understanding that the physical world contains natural scarcity, and that the abundance comes in our subjective experience - things like love, beauty, joy, and meaning can become decoupled from material consumption (to a certain extent), and that this is a safer path for humanity to take, rather than to treat energy and materials as abundant and aligned-AGI as the cure-all.

That said, I'm looking forward to the next piece and where you take this train of thought - diversity of perspectives is the best way to understand a complex topic like this one! And I'm also happy to schedule a chat if you'd like to compare notes :)

I don’t think scarcity is the main cause of wars. There aren’t many wars that I can think of where scarcity is the main cause—although there are a lot of new arguments that various eras of climate change drove some—like for example the 17th C. But, even then, the stated causus belli was almost always ideological. Once upon a time, most wars were about what we would call glory and plunder. Then many were about religion or ideas of human liberty and dignity. Wars continue now in times of relative abundance—Ukraine is not a war about scarcity, nor is the Syrian conflict. The Libyan Civil War is not about scarcity, though competition over abundant resources are central to it, but about who will rule. AI might make ideological wars more vicious. Anyways, my small quibble—interesting article, thanks.