How to Fight Ocean Plastic

Today, thousands of creators led by Mr Beast and Mark Rober are banding together to focus on a single issue: ocean plastics. We’re raising awareness of the problem and money to solve it. Because it’s a huge problem. You can help by reading this article, sharing it, and contributing.

Plastic is everywhere.

It’s in the food you eat.

It’s in the water you drink.

It’s in the air you breathe.

And not just a bit.

You eat a credit card’s worth of plastic a week.

Your body is replete with it.

How does it affect you? We know nothing.

It might make you sterile or accelerate puberty.

It might give you cancer or make you obese.

And a lot of it comes from plastic at sea.

Millions of tons of it, killing millions of birds and fish.

Here’s a rundown of where it comes from and where it goes, how it kills animals, how it ends up in your gut, and what you can do about it.

A Sea of Plastic

Every body of water on earth is loaded with plastic.

This is a dying Bryde’s Whale (30s video). It had too much plastic in its stomach.

Millions of birds also perish, their stomachs full of plastic.

Virtually all birds eat plastic.

Other animals simply get caught in plastic.

One million animals are killed every year by the plastic we generate.

A lot of this plastic reaches the ocean.

But a lot of it washes back ashore.

The plastic that doesn’t wash ashore stays in the water, sometimes for decades, breaking down into smaller and smaller pieces and floating in the middle of the ocean, other times sinking to the depths to remain there forever.

Plastic doesn’t degrade easily. It’s one of the main reasons we use it. It lasts for a long time, from about 5 years for a cigarette butt to 600 for a fishing line.

Our fossil record will be the Plastic Era.

How Much Plastic Is There?

Humans have produced about 6000 million tons of plastic since World War II. We add 300 million (300M) tons every year.

That’s about 40 kg of plastic per year for every person in the world. That’s like filling the entire surface of Belgium, Austria, or Massachusetts with a 10 cm layer of plastic. Every year.

The production rate is growing at 4% per year—exponentially. That means production doubles every 18 years.

Of those 300 million tons of plastic we generate a year, about 220-250M tons become waste. Of these, more than half are managed, either by recycling, incineration, or being buried in landfills. Of the remainder, some leaks onto land, some is openly burnt, and about 10 million tons reach the ocean.

That’s the number we’re worrying about today: ~10 million tons of plastic reach the oceans every year1. That will triple to about 30 by 2040 if we don’t do anything.

Over the years, this plastic accumulates. In 2018, there was a total of 150M tons in the ocean. The ocean will contain 1 ton of plastic for every 3 tons of fish by 2025. By 2050, the oceans may have more plastics than fish2.

How Does Plastic Reach the Ocean?

About 20% of the plastic comes from sea ships, especially fishing. The rest comes mainly from about 1,600 rivers and from coasts.

Not all countries are equally polluting. The Philippines alone accounts for one third of the river plastic that ends up in the ocean.

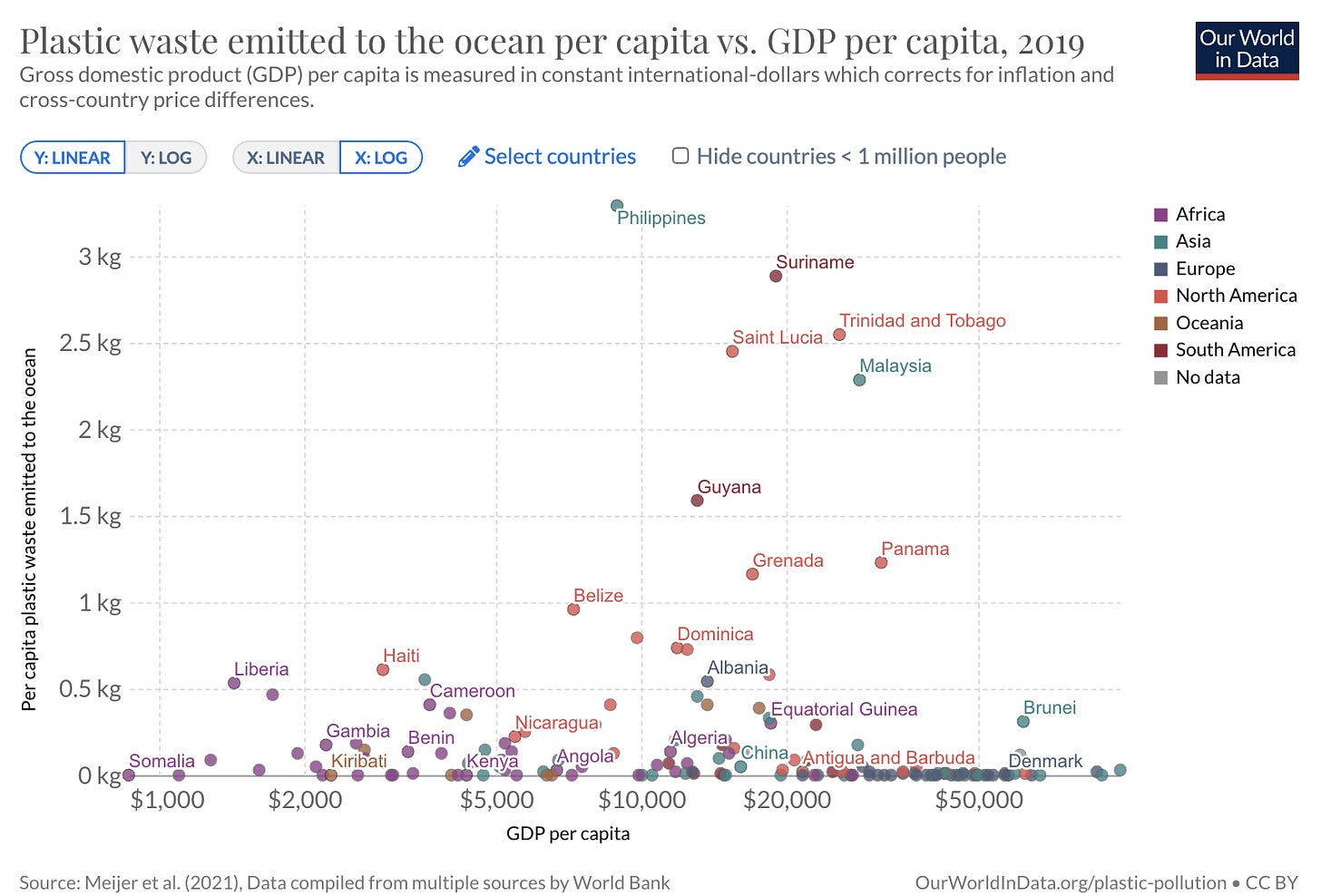

Most of the plastic in the ocean comes from a few countries in Asia.

This is not surprising since Asia has 60% of the global population. But not only are there more Asian people, they also dump more plastic into the ocean per person.

This map shows the sources of plastic pollution in the world. You can see the big bubbles in the South-East Asian Archipelago. For example, the rivers that serve Manila, the capital of the Philippines, account for 1% of all ocean plastic!

That’s right: even if developed economies consume much more plastic, they pollute 30x less per citizen than countries like Malaysia.

There are three key factors that determine how much a country pollutes the ocean with plastics:

How much plastic they generate.

How well they manage waste.

How likely it is for poorly-managed plastic to reach the ocean.

For example, a Brit generates about twice as much plastic as a Filipino, but the Philippines manages its waste about 100 times worse than the UK.

And that mismanaged waste is much more likely to reach the ocean.

You can see, however, that mismanaged plastic is about 50x times more likely to reach the ocean in the UK than in Saudi Arabia. Why?

“The authors of the study illustrate the importance of the additional climate, basin terrain, and proximity factors with a real-life example. The Ciliwung River basin in Java is 275 times smaller than the Rhine river basin in Europe and generates 75% less plastic waste. Yet it emits 100 times as much plastic to the ocean each year (200 to 300 tonnes versus only 3 to 5 tonnes). The Ciliwung River emits much more plastic to the ocean, despite being much smaller because the basin’s waste is generated very close to the river (meaning the plastic gets into the river network in the first place) and the river network is also much closer to the ocean. It also gets much more rainfall meaning the plastic waste is more easily transported than in the Rhine basin.“ Source.

So countries with lots of rain and where plastic waste is generated close to rivers and the sea are much more likely to see their garbage reach the ocean.

That’s the reason why the Philippines is the world’s worst polluter:

They have 110M people.

They generate a fair amount of plastic per person.

Their garbage is very poorly managed.

They are a country with lots of rain, short rivers, and cities that are very close to the rivers and the coast.

Of all of these factors, the biggest one is garbage management, since countries like the UK are broadly similar in all aspects except for that one.

Where Does Plastic Go?

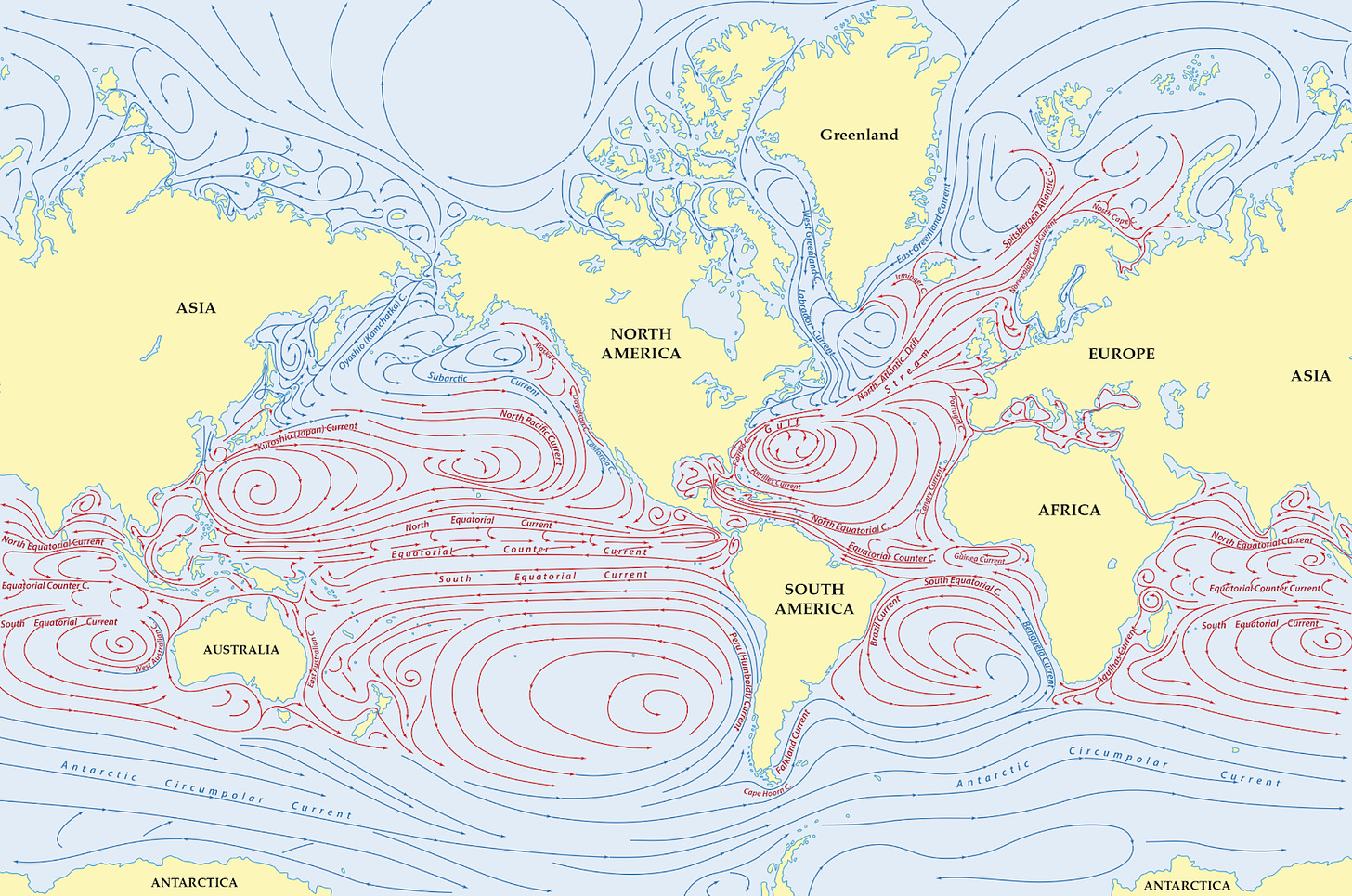

But garbage travels. Thankfully for the South-East Asian Archipelago, ocean currents drag plastic to the middle of the ocean.

This tool is fantastic to get a good sense of where a certain plastic dump would end up. The result is usually the Great Garbage Patches. There are 5 in the world:

They basically concentrate wherever water turns around in a circle, in what are called ocean gyres.

However, these garbage patches are not mountains of plastic floating in the ocean. Rather, they are areas in the sea where there are billions of microplastics floating, broken down by the sun, waves, and salt. Like these:

So when you take a filter and drag it in a Great Garbage Patch, you end up with this:

These microplastics are eaten by fish, birds, plankton...

But the 10 million tons of plastic we add to the ocean every year don’t all go to the Great Garbage Patches. In fact, only a minority does. For starters, about 50% of the plastic sinks.

50% of garbage plastic is denser than seawater. But some of the plastic that floats can sink over time as it gets colonized by barnacles, mussels, and other organisms. The result is that the depths of the ocean become littered with plastic too. This is from a depth of 2300 meters3:

The Mediterranean Sea is a very sad example. Being enclosed, plastic there doesn’t spread out. As a result, the Sea already has 1 kg of plastic for every 2 kg of plankton. Microplastics reach record concentration levels: 1.25 million fragments per km2, almost four times the level of one of the five Great Garbage Patches. The countries that dump the most plastics into the Mediterranean Sea are Turkey (144 tonnes/day), Spain (126), Italy (90), Egypt (77), and France (66).

Here’s one good piece of news: the deep seas have substantially less plastic than we would expect. Why is that?

Most plastic washes back ashore!

Why is this good news? You tell me how feasible it is to go fish plastic from 2000 m under the sea. Or to clear up millions of square kilometers of Great Garbage Patches or polluted land areas. But if plastic concentrates on the coasts, those are relatively small areas to focus on!

So in summary, most of the plastic that goes into the ocean ends up back onshore, or remains within 5 km of the shore, where it can be eaten by land animals, fish and birds. A smaller share goes to high seas, where it floats. Some of it sinks over time, littering the ocean floor.

Over time, these plastics break down because of the sun, the wind, and water erosion through salt and waves. This divides them into smaller and smaller microplastics, amounting to billions of pieces. That’s true whether they stay on the coast4, float in the sea, or sink.

Both types of plastic pieces, big and small, are eaten by animals.

Plastic Animals

When animals eat large pieces of plastic, they can’t easily evacuate them. That reduces their stomach capacity, which reduces their sense of hunger, so they become under-nourished, and die. Even those who can eat enough to sustain themselves on a day-to-day basis may not be able to accumulate enough food for a migration, which requires a lot of fat, impossible to accumulate with plastic-laden stomachs.

Consuming plastic doesn’t just make animals hungry. At worst, these plastics can cause intestinal blockage, ulcers, cell deaths, perforations, and wounds. All of these impacts almost always lead to the death of the animal.

This is how one million animals die every year because of plastics.

Summarizing: We produce hundreds of millions of tons of plastic, of which ten million end up in the ocean every year. All this plastic destroys our beaches and oceans, and kills millions of animals. It reaches the depths of our oceans and the height of our mountains. It’s everywhere. And it’s only getting worse. We are in the plastic era.

And if that doesn’t make you sad and energize you to want to solve this (we’ll see how in a moment), maybe you can be more selfish: remember that these animals that eat plastic are then eaten by bigger animals, who also store the plastic, and so on, eventually making its way up the food chain until some of it reaches us humans.

A study of microplastics in mussels and oysters cultivated for human consumption estimated that an average European shellfish consumer could ingest up to 11,000 pieces of microplastic per year.

Human Impact

A Credit Card a Week

A study of 76 fish bought from an Indonesian market and 64 fish bought in a Californian one showed that about 25% of fish had plastic debris in their gut.

A sampling of mussels in six European locations throughout France, Belgium, and the Netherlands showed microplastics in every organism. This is even worse than for fish, because you might not eat the fish’s guts, but you eat shellfish whole.

“The presence of microplastics in marine species for human consumption (fish, bivalves and crustaceans) is now well-known. As an example, in Mytilus edulis and Mytilus galloprovincialis of five European countries, the microplastic number has been found to fluctuate from 3 to 5 fibers per 10 g of mussels.” Source.

2.6B people depend on the ocean for their primary source of protein.

This ocean plastic is thus one of the main contributors to the plastic consumed by humans, which has been estimated to be between 0.1 g and 5 g of plastic every week—a credit card weighs 5g—or about 18 kg per year. It is not, however, the biggest contributor. That would be the water you drink, especially bottled water. Over 80% of water samples in 14 countries contained plastic. That rate was 94% in the US.

The result is that we all have plastic inside. Of 47 human samples tested in a study, 100% had traces of chemicals from plastic.

“The presence of oral, dermal, and inhalation exposed microplastics is found in feces, colon, placenta, scalp, hair, hand skin, facial skin, and saliva.” Source.

Health Consequences

How bad is this? We don’t know yet. Honestly, it’s probably much better than it could be. Imagine if we realized that 50% of people died 40 years after consuming plastics. We’re not there. But we have lots of clues indicating that plastic is not that great for us.

“Plastics are implicated in the obesity epidemic and in other metabolic diseases such as diabetes and heart disease, as well as cancer and reproductive problems and neural problems like attention deficit disorder. If you look at the trendlines of non-communicable diseases around the world, you see there is a correlation between exposure to these [plastic] pollutants.”—Frederick vom Saal, distinguished professor emeritus of biological sciences at the University of Missouri.

The global epidemic of obesity is quite connected with plastics.

Common plastic additives, including phthalates, BPA and BPS, disrupt our hormones, and have been linked with reproductive and developmental disorders including breast cancer, blood infection, early onset of puberty and genital defects.

The accumulation of microplastics in the liver and kidney causes disturbance of energy and lipid metabolism as well as oxidative stress.

So there’s plastic everywhere and it’s not good for the earth, for animals, or for humans. What can we do about it?

Clean Up the Ocean

Let’s summarize the problems here:

We have an overall problem of just lots of plastic generation that is not fully processed

We have another problem around ocean plastic, namely 10 million tons a year that grows at 4% every year, which will mean ~30 million tons a year in 2040 if we don’t do anything.

This plastic accumulates in rivers, on the coasts, breaks down into microplastics, floats in the oceans, and also sinks.

This kills millions of animals directly.

It also makes it into the food chain, which then ends up in humans, who consume a fair amount of plastic every week.

We don’t know exactly what this plastic does to your health, but it doesn’t look great.

So we want to reduce the amount of plastic that ends up in the water as much as possible, for ourselves, for animals, and for the earth.

This problem is true everywhere, but it especially originates in South-East Asian rivers and coastlines.

I will further break down the problem and go into the details of how to solve it in the premium article of this week: what about drinking water? The air we breathe? Recycling? Replacing?

But since the biggest part of the problem is in rivers and on coasts, one thing we can do today is to clean that up and try to stop it from reaching the ocean in the first place.

That’s why Mr Beast, Mark Rober, and hundreds of creators like me have teamed up to raise $30 million to clean up 30 million pounds5 of plastic6.

This money will go to two organizations: the Ocean Conservancy and The Ocean Cleanup. I wanted to make sure that this money was going to be well spent, so I first made sure that both the Ocean Conservancy and The Ocean Cleanup are legit—they are.

Next, I wanted to make sure their initiatives would have an impact.

Ocean Conservancy cleans up the coasts by organizing coastal trash cleanup parties. They’ve been around for decades, and do what they say they do.

The Ocean Cleanup is extremely ambitious, and ambition always carries risks. It’s been in the news recently because they tried to clean up the North Pacific Great Garbage Patch with ships, but the project wasn’t extremely successful. This money, however, would go to a much better use: systems that catch plastic in rivers.

If this system works, it could be a radical way to solve the river plastic problem, and as we now know, this is the biggest source of plastic in the ocean, so it could solve most of that problem. We won’t know until we try.

The $30 million we’re raising would go specifically to these campaigns:

Beaches

With the experts at Ocean Conservancy, we’ll send professional crews to clean up some of the most iconic, vulnerable beaches on the planet. We’ll also be holding safe, locally-hosted events leveraging Ocean Conservancy’s International Coastal Cleanup (ICC) network so #TeamSeas members can roll up their sleeves and see the impact they’re making firsthand, one pound of trash at a time. The ICC is the largest beach cleanup network in the world (more than 340 million pounds of trash have been collected from beaches in its 35 year history!) and with your help we’ll make it even bigger.

Rivers

For our rivers, #TeamSeas will fund Interceptors™, The Ocean Cleanup’s cutting-edge river cleanup technologies that collect trash before it can reach the ocean. The Ocean Cleanup has several Interceptor™ solutions already deployed at some of the world’s most polluted rivers to catch plastic and trash upstream. #TeamSeas will support the expansion and continued operation of this work as The Ocean Cleanup takes aim at the 1% of rivers which contribute 80% of the trash flowing into the ocean from rivers.

Oceans

Lost, abandoned and discarded fishing gear – or ghost gear – is some of the deadliest ocean trash, and is super tricky to recover. #TeamSeas will work with Ocean Conservancy’s Global Ghost Gear Initiative® to go to ghost gear “graveyards,” where we’ll identify and float the abandoned gear to the surface. From there it’ll be hooked onto boat cranes and removed from the ocean forever.

To donate, you can go to the #TeamSeas site, or directly to The Ocean Cleanup’s or the Ocean Conservancy’s sites7.

I will match the first $1,000 that you guys donate. Just respond to this email with a screenshot of the proof of donation.

Additionally, if you’ve ever wanted to become a premium subscriber, now is a good time: over the length of the campaign, I will donate 100% of the profits I make from new subscriptions. This way, you’ll receive more information—including about plastics. This week, I’ll go into more detail on the problems (for example, how plastic ends up in our drinking water, or what are the specific sources of microplastics), and other ways to solve the plastic problem—including how to limit the plastic in your diet.

I understand not everybody can contribute money. But that’s not the only way you can help. The other way is by spreading the word. If you think this article has helped you understand the ocean plastic problem better, please share it with everybody you know!

Let’s go #TeamSeas!

Depending on the source, you’ll get anything between 8 and 12 million tons. The exact number doesn’t matter. At this point, it’s just the order of magnitude that does.

By weight

One side goal of this blog: to teach the metric system to Americans! And if you’re not convinced yet, watch this.

A study found hundreds of microplastics per square meter, in a pristine part of the Pyrenees mountain range.

Alright, Americans. You can have this “pounds” instead of kg. 30 for 30.

This initiative alone would clean up 0.1% of the plastic thrown in the ocean this year. More important than that: it will raise awareness of this problem and help the organizations that fight this fight to get better at their operations so that they can keep operating and become more efficient over time. For example, the ships that take the plastic out of rivers seem like an amazing partial solution to the problem of river plastic, especially well suited for places like the Philippines and South-East Asia in general.

Ocean Conservancy and The Ocean Cleanup are both 501(c)3 organizations and contributions are tax-deductible in the US. European donors can give to The Ocean Cleanup for #TeamSeas and take a deduction as well.

It was mentioned that the waste management in the Philippines is 100 times worse than the UK. While this might be true , the UK exports 2/3rds of its plastic waste mostly to poorer countries such as Malaysia, Indonesia and the Philippines. That doesn't mean good waste management, surely? It would be interesting to know how much of this illegal dumping contributes to the waste run off to the rivers and oceans. https://www.bbc.com/news/uk-51176312

I like your two charities, but I think that you have ignored the elephant in the room! The obvious solution would be for rich countries like the US and Canada etc. to spend "small bucks" of tax money to improve waste management practices in the countries that are the source of the problem, starting with the Philippines. Here in Canada, we could easily save more than enough money by dropping our meaningless nuisance virtue-signaling programs to ban plastic straws and shopping bags.

The myopia that drives well-meaning people (including Justin Trudeau) to focus on the smallest parts of this problem while ignoring the largest parts seems to dwarf a similar form of myopia in the realm of abating global CO2 emissions. But at least in that field, there are vital needs that are being met by China's and India's and Africa's increases in coal-fired generation. I can see no similar needs being met when the world's rich countries sit idly by (or distract ourselves with trifles) while a few countries throw most of the world's plastic trash into the oceans.