Two centuries and a half ago, two world regions had a fertility revolution. Soon after, both regions also had a political revolution that shattered the world order. In the process, they changed world history in a way that reverberates to this day. This is the story of what happened to children in New England and France, and how it changed the world.

I’ve been studying fertility for over a year now, and I’m starting to talk with experts. I chatted with Lyman Stone, a demographer active on Twitter with some interesting threads. He gave me some pointers for this article. In upcoming articles, I will cover several aspects of world demography based on my conversation with him:

Children Mean Power

The Man Who Made 50,000 Babies

The integral interview with Lyman Stone

Subscribe to receive them all.

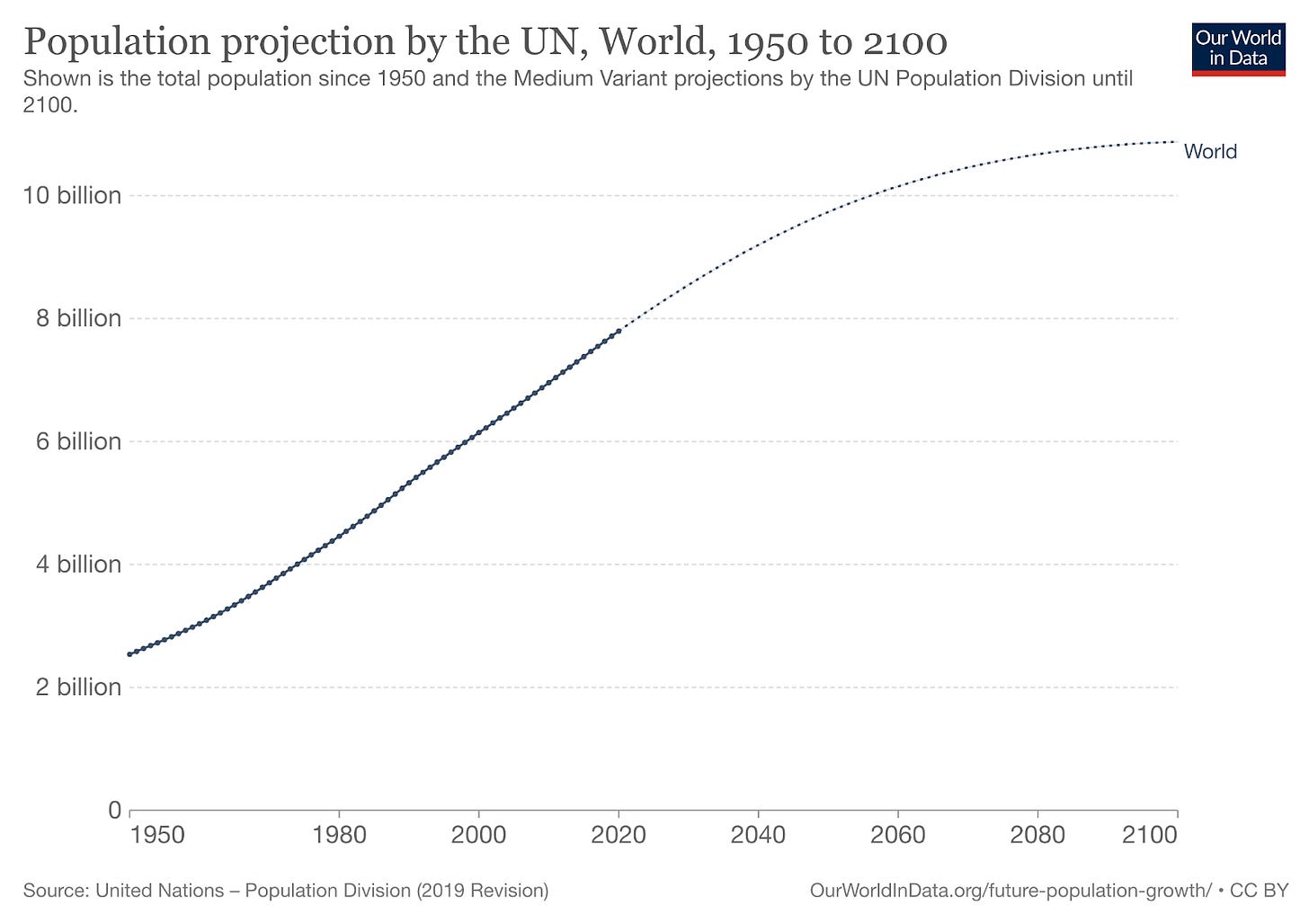

The fertility rate of the world is dropping.

If it continues this way, the world’s population will start shrinking at the end of this century.

Some people think the fertility drop is good. Some think it’s bad. I think it’s a catastrophe, but I’ll address it in another article. Regardless of whether you want to fight or accelerate, you’ll want to understand why it’s happening.

Conventional Wisdom on the Demographic Transition

Until recently, conventional wisdom and demographers assumed that the cause of the drop in fertility was a reduction in the cost-benefit of having children.

First, kids were less economically useful:

As standards of living improved and people moved from the farm to the city, the economic value of kids dropped because they were not productive free farm workers anymore.

As sanitation improved, fewer children died, so parents didn’t need to overshoot by having more kids to make sure they had enough support during their retirement.

At the same time as the economic benefits decreased, the costs increased:

Parents had to invest in them for two decades’ worth of education so they could get a decent job—which then paid them, not the parent.

Add to that increases in housing costs in the city and higher standards of living (more clothes, more entertainment…)

More costs and fewer benefits meant fewer kids.

That’s not half the story.

If this were true, we should see that fertility dropped where the Industrial Revolution started: places where standards of living suddenly exploded, while people migrated to the cities.

Did Rising Standards of Living Cause Fertility to Drop?

Given that the Industrial Revolution took off in the 1800s in the UK and the Netherlands, their fertility rate should have dropped first.

This is not the case.

Instead, fertility dropped first in New England and France, and it dropped in the mid 1700s, not the 1800s! This is France:

The same is apparently true for New England. This is for Nantucket, Massachusetts and New Hampton, New Hampshire:

Back then, New England and France—NE&F from now on—were poorer than the UK and Netherlands. For example, the GDP per capita enjoyed by England and Wales in 1750 was only attained in France in 1850.

NE&F also had a much lower share of urban population. It took them over a century to achieve the rate of urbanization of 1750 England!

Meanwhile, the demographic transition happened in England between 1870 and 1920!1 More than half a century into the Industrial Revolution.

If standards of living or urbanization were the triggers for fertility drops, we should have seen fertility drop in the Netherlands and England, not NE&F. The story that the improvements in standards of living caused the drop in fertility might play a part in a few countries, in a few eras, but they can’t explain New England and France. Conventional wisdom is wrong.

Could it be sanitation?

Did Sanitation Drop Fertility?

It might have had an impact.

But usually mortality goes down first, followed by fertility. This gap results in a “baby boom”, as we’ve seen in the 20th century. But in France, both went down at the same time. Why?

Did Less Marriage Drop Fertility?

Married people have more kids. Maybe for some reason the French delayed marriage or simply married less in the 1700s? No.

In 1700s France, celibacy was stable and then went down after the revolution2.

Later marriage doesn’t explain it either: marriage age was stable in the 1700s and only went down in the 1800s.

Fewer kids out of wedlock also doesn’t explain it: there were more after 1740. The same is true for Nantucket.

Whatever reduced fertility in France, it can’t be linked to less marriage. It must be people having fewer kids inside the marriage. So why were married people having fewer kids, if it wasn’t because of better standards of living or sanitation?

Could it be the same root of their other revolutions?

Fertility | Revolutions

The Roots of Political Revolutions in New England and France

“In France, it seems highly unlikely that the reversal of the marriage pattern—occurring at the same time as the French Revolution and the weakening of the Catholic Church—happened to be a coincidence.”—On the Origins of the Demographic Transition. Rethinking the European Marriage Pattern, Faustine Perrin, 2020.

NE&F were the two Western regions that went through their fertility transition early, in the mid 1700s. A few decades later, the very same regions also had political revolutions.

The one in New England—the American Revolution—was against the established order, and more specifically the unfair power of a physically distant king.

The French Revolution was against the established order, and more specifically the unfair power of a socially distant king.

The parallel is striking. Is this a coincidence? Apparently not.

The US Declaration of Independence happened in 1776, and the former colonies signed their Constitution in 1787. Two years later, in 1789, the French Revolution began.

Why, after millennia of monarchies, suddenly two areas thousands of kms apart decide at the same time that their political system doesn’t make sense anymore? Of course, it was the spread of ideas.

Since the proliferation of the printing press in the 1500s, ideas like those from the Renaissance, the Enlightenment, or the Scientific Revolution spread like wildfire. The 1700s were especially fertile with Enlightenment ideas from philosophers like Hume, Locke, Kant, Diderot, Montesquieu, Rousseau, or Voltaire.

Some of their ideas included reason, liberty, fraternity, the separation of church and state, secularism, and the sovereignty of the people.

In the US, given the obvious exploitation of the colonies from the British motherland, the ideas of Life, Liberty, and the Pursuit of Happiness quickly translated into political action. In France, it took a bit more time¸ maybe given the older history and physical closeness of the king—but eventually similar ideas of Liberté, Égalité, Fraternité also translated into political action.

It turns out that these same ideas might have caused the fertility drops in New England and France. Specifically, secularization.

Liberté, Égalité, Fécondité

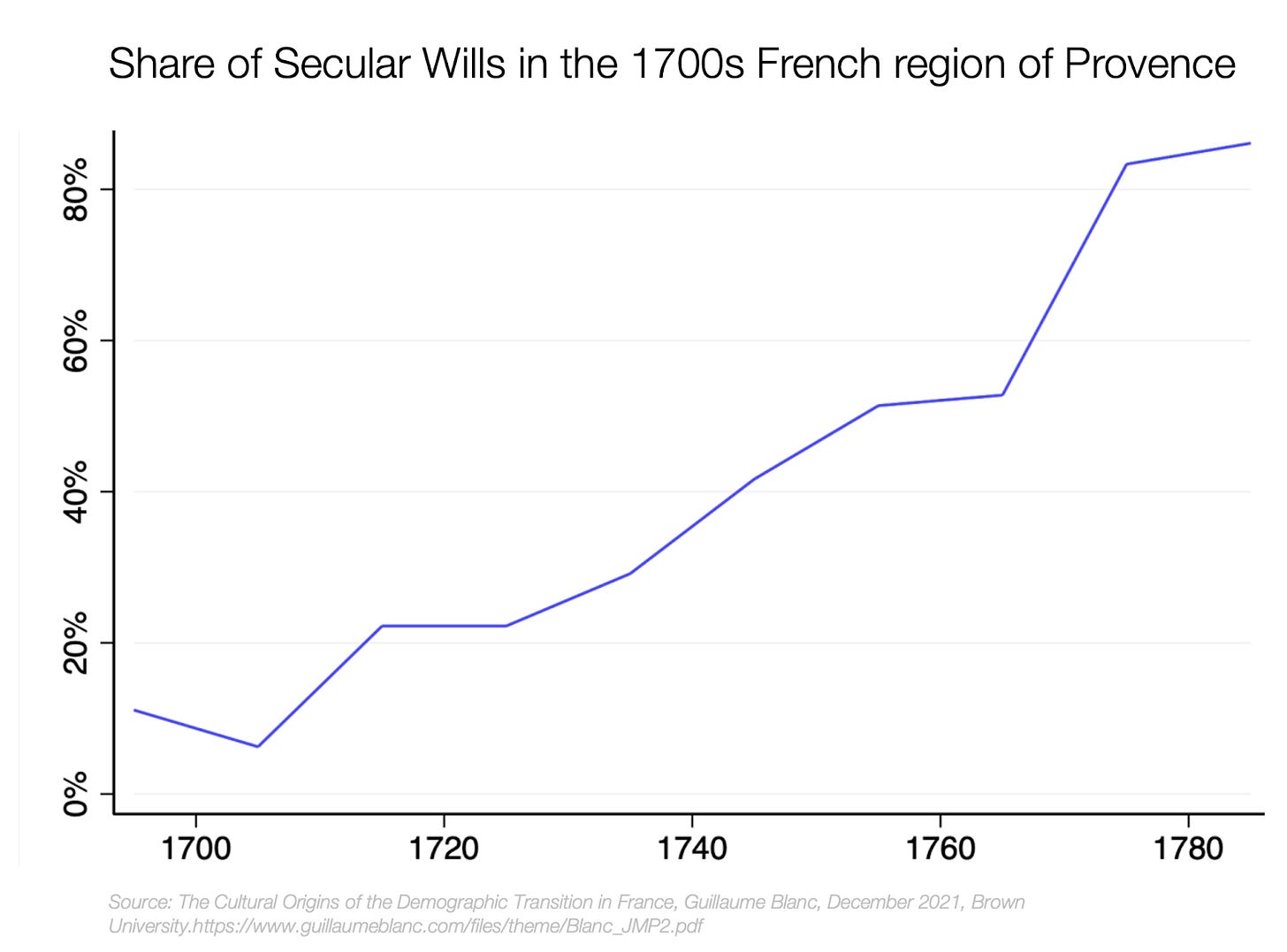

“Using census data available in the nineteenth century, I show a strong association between secularization and the timing of the [fertility] transition.”—The Cultural Origins of the Demographic Transition in France, Guillaume Blanc, Brown University, December 2021.

I mentioned before that the fertility drop in France came despite people marrying more and younger. In other words, it had to come from fewer births within marriages. But why would married people have fewer kids?

This paper figures out fertility per region in the 1700s France3. Then, it compares that to estimations of secularization, such as how many times the Church is named in death wills, and the amount of conservative clergy in an area4.

In areas where the clergy was more conservative5, people had more kids, and this effect started in 1760.

This was inherited: afterwards, as people moved from one region to the other, the more secular the region of origin of their ancestors, the fewer kids they had!

According to the paper, it does look like it was secularization that dropped fertility, rather than many other factors—urbanization, religiosity before the 1700s, literacy…

How exactly might have this worked? What was the underlying mechanism? Maybe it was… a sexual revolution?

The Sexual Revolution of the 1700s

When I think about sexual libertines, my mind goes to people like the French Marquis de Sade6 or Venetian Casanova, who escaped to Paris. Why were there so many French libertines in the second half of the 1700s?

The Catholic Church has always aggressively pushed reproduction. Today, it still pushes people to marry (more marriage, more kids) and to avoid abortion. Homosexuality is begrudgingly accepted—where it’s not opposed. Abstinence is promoted. I guess it’s done so that people marry younger to have sex, which means more kids in the long term. It also probably reduces children out of wedlock, who might be less likely to become Catholic themselves.

The rational logic is clear: the more kids Catholics produce, the more customers followers the Catholic Church has.

But what we see today is nothing compared to what the Catholic Church required before: ejaculation had to happen inside the vagina, and everything else was discouraged or even banned: withdrawal, masturbation, “unnatural positions”, prostitution… Obviously, abortion and infanticide were big no-nos.

But secularization took hold in France in the mid-1700s. Wherever it increased, people felt less forced to follow the Church’s precepts, which had two consequences:

This reduced the number of kids desired.

People were more OK having the number of kids they actually desired—instead of the kids they felt pressured to have.

How did they achieve this? With fatal secrets:

“Rich women for whom pleasure is the greatest interest and the only occupation are not the only ones who consider the propagation of the species as a dupery of olden times; already the fatal secrets unknown to any animal but man have penetrated in the countryside: nature gets cheated even in the villages.”—Moheau, 1778.

The best guesses of what these fatal secrets are include abstinence, masturbation, mutual masturbation, oral sex, anal sex, and maybe withdrawal7. It is reasonable that, as the Church’s authority on people waned, so did its pressure to have babies and avoid contraception. People started to have less sex that ended in insemination, and there were fewer kids.

Summarizing, here’s what some scholars believe happened in France in the 1700s:

Before the mid-1700s, the Church pushed Catholics to have lots of kids and no contraception.

The ideas of secularization spread across France in the mid-1700s.

As they did, people became more secular in some places.

Wherever they did, they had fewer kids inside their marriage.

They probably did that with a series of contraceptive methods, such as masturbation or withdrawal.

The result was a drop in fertility way before anywhere else in Europe, including richer and more urban places like England and the Netherlands.

These same secularization ideas were also the cause of the French Revolution, which means these ideas caused both political and fertility revolutions.

In summary, what caused a drop in fertility was primarily ideas, not standards of living or sanitation.

What about New England?

No Fecundation Without Sanctification

About half the reduction in children in Nantucket was because people married later, and half was because they had fewer children during those married years.

The older age of marriage might have been due to economics or ideas such as secularization. But secularization is more likely, since you need ideas of contraception (whether abstinence, withdrawal, or anything else) to reduce children within the marriage. Conversely, economic factors tend to postpone the average age of marriage and keep more people single.

New England was being hit at the time by the ideas of Enlightenment and secularization that would result in the US Declaration of Independence and Constitution, which doesn’t name God or religion a single time. This was a reflection of the Founding Fathers, most of whom believed in reason more than religion. Jefferson and Madison promoted a religion freedom bill.

Lyman Stone told me that New England was indeed going through a secularization process that was having the same impact on fertility as in France, which can be seen in Church attendance. I couldn’t find much data on the topic, but the little I found corroborates the idea.

“Early Puritan churches in New England had not suffered for want of members. The same could not be said by the early 1730s.

By then, […] Church membership had dwindled when the children and grandchildren of the original founders did not attain the same level of spiritual intensity necessary for a religious conversion experience. A general malaise seemed to be afflicting New England’s churches and their energetic Utopian beginnings seemed far away and irretrievable.”—Source.

Stone told me he will have a paper on the topic in the coming months to confirm these ideas. I’ll look forward to it.

The Twin Revolutions of Politics and Fertility

If the data about France is right, the main driver of fertility reduction in that country in the 1700s was secularization, which also drove France towards the French Revolution.

According to this paper, diffusion from France also drove the reduction in fertility across Europe (emphasis mine):

“The fertility decline [in Europe] took place earlier [than the 19th century] and was initially larger in communities that were culturally closer to the French, while the fertility transition spread only later to societies that were more distant from the cultural frontier. This is consistent with a process of social influence, whereby societies that were linguistically and culturally closer to the French faced lower barriers to the adoption of new social norms and attitudes towards fertility control.”—Fertility and Modernity, Enrico Spolaore & Romain Wacziarg, 2019

As a result, maybe industrialization was just an accelerator (or an enabler) of the drop in fertility in Europe, but the ultimate cause was secularization.

If we trust Lyman Stone’s comments about Massachusetts, the same process might have happened in New England.

Both France and New England had revolutions against monarchies in the 1700s, while the rest of Europe revolted against their monarchs in the 1800s. Just as their fertility was dropping.

If this theory is true, industrialization is not the only culprit of the global fertility drop. Ideas—and more specifically secularization—might have had an outsized role. If that was true, countries that maintain their religiosity might avoid the fertility drop.

Is that what we see?

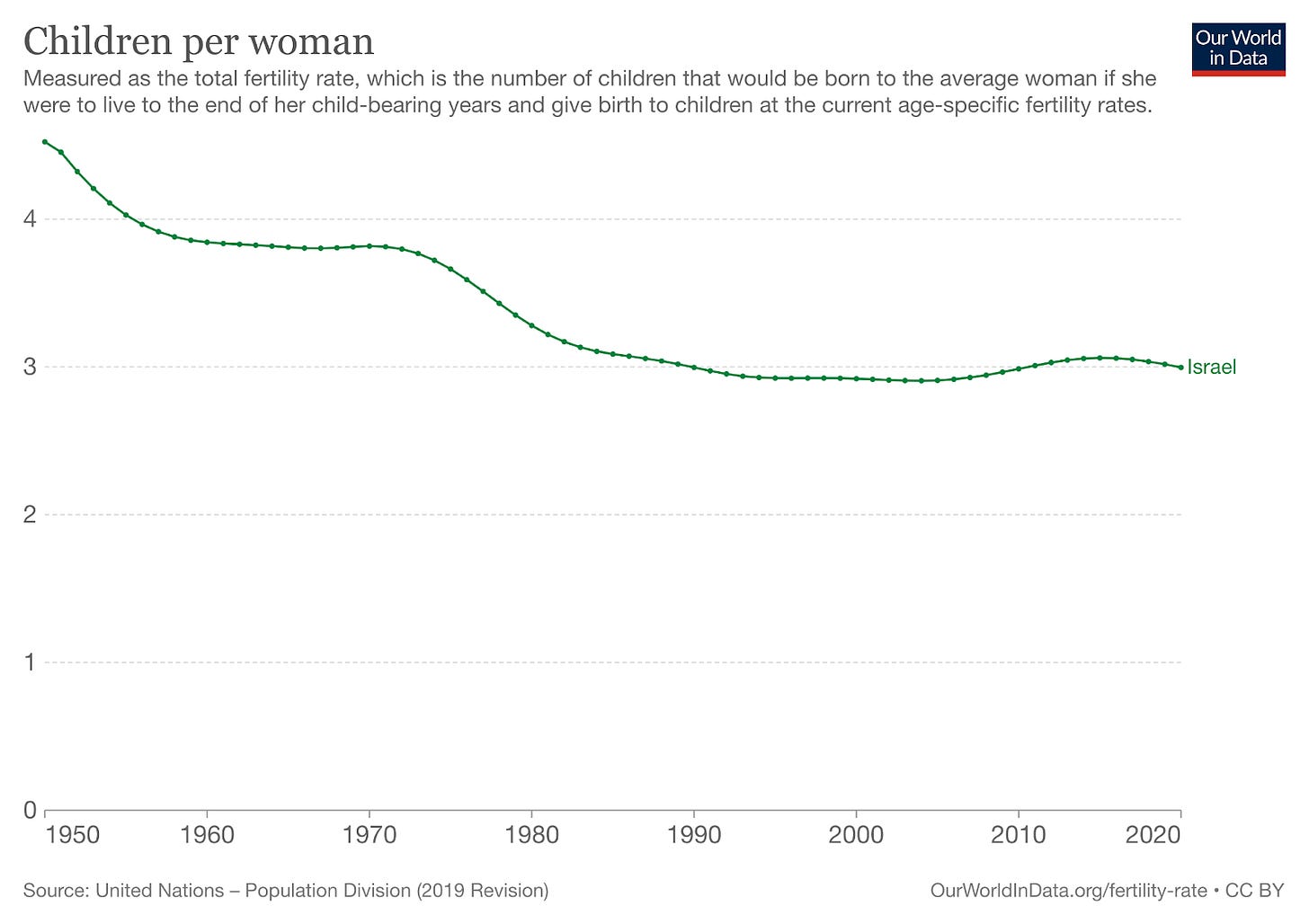

Could Israel have a higher fertility due to the greater importance of religion?

Religion is not the only factor, as even secular women have more than two children today (after a 20 year interlude below two). But, in Israel, the more religious, the more kids.

Why does this matter? Because if reductions in fertility are heavily influenced by culture, they can be reversed.

A culture that insists on having few kids will have few kids.

A culture where it’s ok to have a lot of kids, the fertility collapse can be reversed.

Religions are one consistent way that fertility has remained high throughout the world. A more religious world probably means a more fertile world.

But it doesn’t mean it’s the only way. It does mean, however, that those who want to increase fertility better start convincing others.

Upcoming articles in Uncharted Territories will cover:

Why we should have more kids

How fertility has determined power in history

An example of how to revert the fertility drop

The integral conversation with Lyman Stone, where we talk about how fertility changed across history and places, including the fertility crashes of Ancient Rome and Greenland, how much economic measures can increase fertility, the role of ideas and culture in fertility, why increased fertility should be a bipartisan goal, the interaction between fertility, development, and pollution, and much more.

Subscribe to receive them all.

Sometimes, standards of living are mediated by education. But in France, the fertility drop preceded increases in education by decades. And even then, it’s not like people wanted more education for their children—which would justify them wanting fewer children—but rather more education was supplied to people, and a law is what pushed more children to have education, in the 1800s rather than the 1700s.

The share of women who never married increased in the 1700s but drastically reverted after the French Revolution in the 1790s.

By looking at census data and genealogies, to get a sense of where and when people were having how many children

Refractory clergy against the request during the French Revolution that all clergymen declare their allegiance to the state.

In July 1790, during the French Revolution, the National Constituent Assembly passed the Civil Constitution of the Clergy, which required all clergymen to swear an oath of loyalty to the secular state. The areas where clergymen did not take the oath (known as refractory clergy or non-jurors) in 1791 is a proxy for religiosity. It turns out that the map that shows that matches pretty well with maps of religiosity two centuries later: “The map of clerical reactions in 1791 was remarkably similar to the map of religious practice in the middle of the twentieth century.”—Religion, Revolution, and Regional Culture in EighteenthCentury France: The Ecclesiastical Oath of 1791. Tackett, 1986.

Whose name can be found in sadism today

Homosexuality fits the bill too, but I couldn’t find quotes on it. My guess is that it doesn’t appear in these texts since they talk about relations between married men and women.

A note on language you might want to consider being more accurate about: Fertility RATE = # of children born to each woman whereas fertility = capability to reproduce. I think most of the time you either mean fertility rate OR reproduction = production of offspring, not that biologically women are less physically able to reproduce. "Fertility rate drop" does not equal "fertility drop," a different metric that would not be measured by number of people.

Very interesting piece. Near the beginning did you mean to say that fertility has decreased because the cost:benefit ratio has INCREASED (rather than decreased) since cost has increased and benefit decreased? The common link between New England (really the American colonies) and France is the Enightenment. The founders were heavily influenced by French Enlightenment thinkers of the early 18th century. I think the suggestion that secularization decreased fertility is reasonable, but it seems likely that decreased child mortality and urbanization also contributed. Something as complex as fertiltilty is not likely to have a single causal explanation. As a biologist I see benefits to a decrease in the global population of humans in terms of less habitat destruction, pollution, release of greenhouse chemicals, and loss of biodiversity. But as the father of two kids I understand the societal disruption that decreased population will cause. If the US wants to reverse the trend, it could take actions to make it less expensive to raise kids, like universal child tax credit, quality pre-K, pre and post-natal health care, affordable preventive heath care, and free/subsidized post high school education or vocational training. The US makes it costly and difficult to raise kids if you're not wealthy, and the lack of universal access to good health care pre and post natal gives the US the highest child mortality rate of any developed country. Not conducive to increased fertility.