Why the World Becomes Progressive

You might have heard about the Urban-Rural Political Divide: In the US, people in cities vote more liberal, and in rural areas they vote more conservative. In fact, this rule is much more fundamental, and its ramifications might drive the political future of the world.

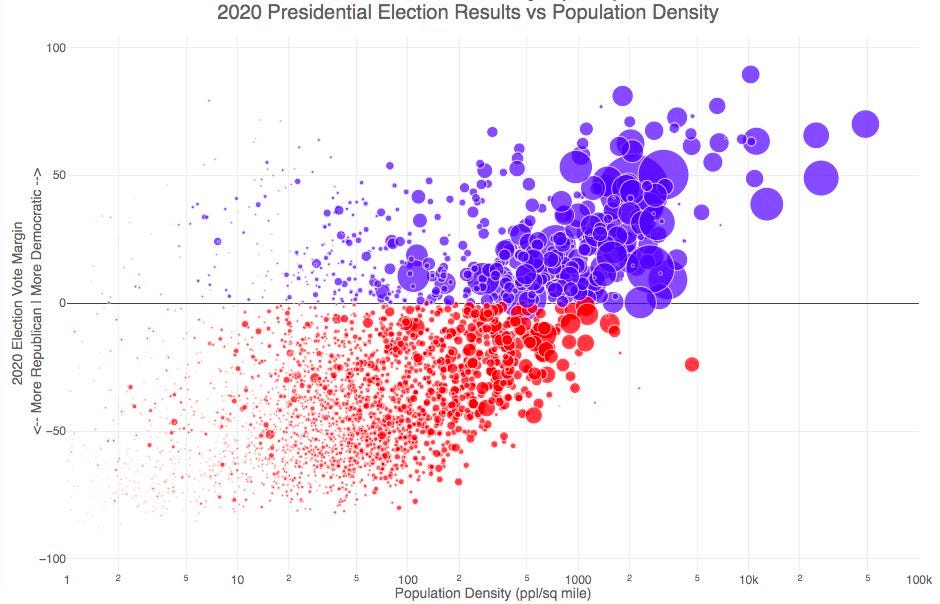

This image represents the urban-rural divide well. Each bubble is a county. The bigger the bubble, the more population. But you can see that the bigger the bubble, the bluer it is too.

In other words, more population density means voters lean more liberal. This is more obvious in this graph:

Bubbles on the left are smaller because population density is lower. They’re also lower, meaning they vote conservative. The opposite is true for the blue bubbles, which are bigger and higher up, in liberal territory. Source.

This begs a few questions:

Where is this happening?

Why is it happening?

When did it start?

What does it mean for the future?

1. Where Is This Happening?

This is not just the US.

It happens in Canada.

It happens in the UK: the more population density, the more people vote for Labour:

And of course, the higher the density, the less people voted for Brexit.

It happens in Germany: more density, more left-leaning vote.

In France, the Gillets Jaunes protests were led by rural areas. And the less population density, the more people voted for Le Pen, the extreme right candidate.

It seems to have happened in Russia in the short period while there were reasonably democratic elections.

It happens in New Zealand:

In this study of 30 European countries, they found that the less density, the more people tended to vote conservative. This trend is not binary, but rather gradual, from cities to suburbs to towns to villages to rural areas.

This paper looked at several countries in Western Europe, and saw the same trend. And it tried to understand what caused the urban-rural divide.

2. Why Is This Happening?

That paper was trying to break it down into its components, and what it found was that there is more left-leaning vote in places with:

More public services.

More population growth.

More wealth.

More education.

More immigrants.

Note here how the paper’s narrative breaks. Some people assume that more immigrants push locals to vote farther right, but the data says the opposite. In fact, the data doesn’t seem to support the narrative at all: Maybe they have the causality lopsided. Maybe it’s not wealth, education, population growth, public services, or immigrants that makes people vote more left, but rather that cities cause all of the above?

Indeed, cities need and fund more public services. Since they have more network effects, they pay more, so they attract more people (including immigrants!), so they grow more (urbanization!). Also, people who want higher education are more likely to go to a city to get it, and to stay for bigger salaries afterwards.

So maybe the causality is the opposite: Cities cause all the things above, but they also cause the left-leaning vote. Why might that be?

I could find two explanations.

Sorting & Hopes

One hypothesis is that there’s sorting going on, which then causes further polarization.

Cities attract some kind of people—the wealthier, more educated, cosmopolitan, progressive, diverse population. That sucks all these people away from rural areas. The ones remaining become a homogeneous bunch: poorer, less educated, more conservative.

Then something else happens: Cities grow, things move forward, people are hopeful. They want more progress. They can’t wait to see the future, and want to accelerate it.

Meanwhile, rural areas are left out. They’re emptying. Wealth leaves, kids leave. The future seems dire. The past seems bright in contrast. People become even more conservative.

Research says this is a part of what’s happening, but not all. Something else is happening.

Urban Psychology

Sometimes, I spend some time at a rural house close to where I live. That house has three houses nearby, and a hamlet about one km away, too small for any business to survive there. The smallest town is about 20m away by car. The city is 1h30 away.

In that rural area, people don’t see the government very often. They don’t see many people, in fact. And the ones they do see are always the same ones. They know each other well. When they have problems, they deal with each other directly. They don’t call the police. That would be seen as unneighborly. If the government does anything for you at all, it’s usually too little and too late.

But on TV, you do see all these immigrants, and all that crime1, and you don’t want that in your community. You also see all that money invested in the cities, but you don’t see much of it. You do see the taxes though.

Why would you vote for a left-leaning party?

Now go to the city. Every day, you come across hundreds of strangers and dozens of businesses. You see immigrants, you see homeless people, you see LGBT people. All this interaction generates empathy: You understand them and you want somebody to help them have the same chances you’ve had.

But it also creates conflicts, so you want the government to intervene. In fact, you might quickly resort to calling the police: You don’t know these people. What might happen to you if you try solving the problem alone?

And if a new problem arises with all the people you deal with, and there’s no rule for that, maybe somebody should come up with a rule, shouldn’t they? Maybe the government should approve a new law?

You also see all the public services you have, and the ones you don’t have yet. You are happy with what works, and want more to fix what doesn’t.

The government is there, everywhere, all the time. You understand where your taxes go, and you might want to invest even more in communal life.

Of course you’ll vote for a left-leaning party that wants progress, because you want things to improve!

A History of Progressivism

It’s not a secret that communism started in the cities, where manufacturers established factories to take advantage of good infrastructure and plenty of potential employees and customers. Rural areas tended to remain conservative, while urban areas became more progressive.

But that’s not just the history of Communism. It’s the history of cities.

The history of communism would make you think that poorer people, like workers, want to change the status quo to access a better life, so they vote left. That people with fewer educational opportunities are left out of wealth and want an opportunity, so they would vote more to the left. But that’s not true at all. It’s the opposite! The richer people are, and the more education they have, the more they tend to vote left. So the story of communism doesn’t fit. But the story of cities does.

Change happens in cities. So cities demand change, they demand progress.

Everything takes longer to reach rural areas. Obviously they want things to stay the way they are: They haven’t seen the changes where they live yet!

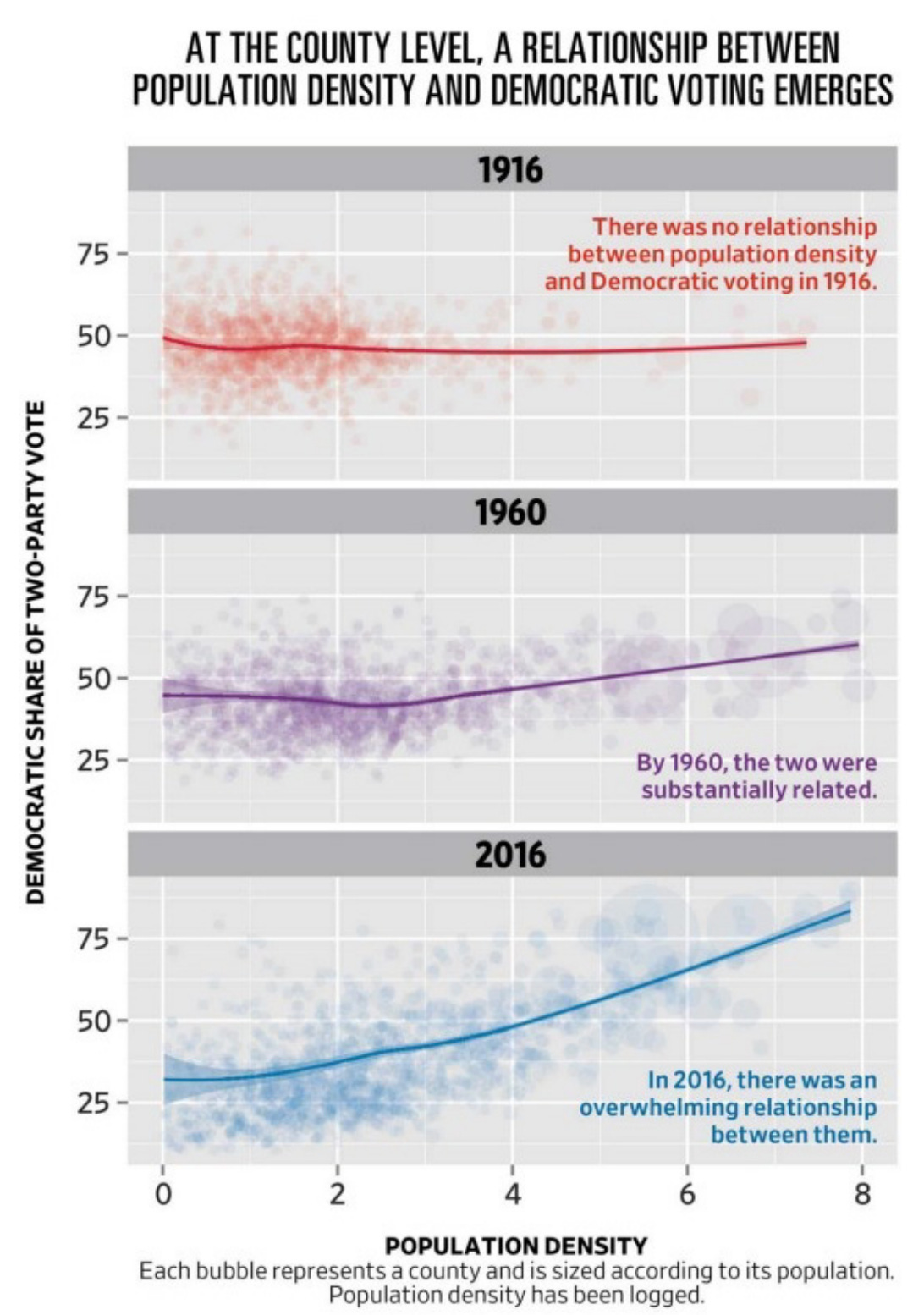

If this is in fact true, then surely we should be seeing this correlation between population density and progressivism over time?

3. When Did This Start?

This trend is not new. Apparently the urban/rural divide was central to the politics of the Athenian Republic.

About the industrial revolution:

At the peak of the industrial revolution, between the end of the 19th Century and the beginning of the 20th, many European and North American countries were divided politically between the interests of rural and small-town dwellers, engaged in agricultural production, and those of urban residents, experiencing rapid change and a new spatial economic order dominated by manufacturing in large agglomerations.—The urban-rural polarisation of political disenchantment: an investigation of social and political attitudes in 30 European countries.

In Germany, this trend has been true for nearly 50 years:

In the US, the story is a bit different.

The trend of voting Democrat in higher density regions barely existed in 1916, grew stronger in the mid-century, and is very strong now. But let’s remember something: Voting Democratic has not always been progressive. In 1916, thanks to the solidly Democratic South, Democrats were more conservative than Republicans. The shift between Democrats and Republicans only began appearing in the 1930s. And the divide in progressivism between the two parties has been growing ever since.

So it’s not a surprise that we don’t see a big polarization in the US in the early 20th century, and that now we can.

There’s another factor.

Urbanization

In the early 19th century, 94% of Americans lived in rural areas. It was still 85% by the mid-19th century. In 1916, less than half the population lived in urban areas. That means that, if you wanted to win, you couldn’t cater to urban populations only. Parties were forced to appeal to both urban and rural citizens.

But urbanization has kept increasing since.

The more urban the population, the more it makes sense to cater to it at the expense of rural areas. Now, with 82% of the US population in urban areas, a party like the Democrats can easily make fun of flyover country and attack gun-owners without fear of losing voters. Meanwhile, the Republicans can easily make fun of minority rights and the “elites”, both of which are indeed urban. Of course there will be more polarization!

This suggests something: Maybe the transition to progressivism has simply been the story of urbanization?

4. What Does It Mean for the Future?

Today, the higher the population density, the more people vote progressive.

It seems like this might have been true in the past too.

If this is the case, maybe progressivism has grown on the back of urbanization.

If this is true, we could make a prediction: That an increasingly urbanized world will keep seeking greater political progressivism.

At the turn of the 21st century, less than half of the world’s population lived in an urban area. Today, that number is nearly 60%2. It will likely be close to 70% by the end of the decade.

If city dwellers want progressive policies, and the entire world is moving to cities, will the world clamor for more political progress?

When US Republicans are concerned about immigration, is that simple dog-whistling, or are they truly concerned about racial displacement? Because if they are, they should stop paying attention to that and start focusing on urbanization instead.

Now the rate of urbanization won’t keep growing forever in developed countries. Most of them are between 80% and 90% urbanized. The only thing that can happen there is more density, which might increase progressivism.

Meanwhile, urbanization is rapidly growing across the world in all emerging economies. Within a few decades, the political ideas of their population might move from hard conservatism to progressive openness.

Of course this is an impression from media being everywhere and more polarized. Crime is at an all-time low.

This graph stops at 2016. I projected to 2022 assuming a constant slope, which seems like a reasonable bet looking at the progress of other regions, which don’t slow down in the urbanization transition until about 70% is reached.

Hi Tomas, nicely written as always - with excellent graphics to illustrate your points.

However, I think it is worth bearing in mind that to call leftist parties "Progressive" is the second best branding strategy in political history. The best branding was for the Russian Bolsheviks (majority).

To make progress is to make change that people will come to see as positive. And perhaps when you look across countries and for a long time you can make a good case for "Progressive" parties making "progress" at least when taken as an aggregate. However, there are problems on the horizon just now.

Crime is at an all-time low - as an aggregate. However, it has seen a severe uptick in the last three years in numerous large American cities. Bari Weiss's podcast, Honestly, has an excellent, nuanced discussion of the intertwining issues. Taking account these intricacies most people would say that progressives tried some new things based on poor understanding and made life very dangerous for small parts of big cities. It is so dangerous in these places that the overall trend lines have changed direction.

Progressives have also decided that homelessness is largely a choice and that cities should accommodate the homeless rather than take measures to get them off the street. Now many cities have become dangerous due to lawless homeless encampments. Again referring to a Bari Weiss project, see this morning's post by Leighton Woodhouse on Common Sense. Many people who support Progressive parties have great compassion for "the least of these," which includes compassion for the soaring number of people dying of drug overdoses in urban homeless encampments where there is not only a lack of drug law enforcement, there is often municipal government material support for drug use.

So, I think there will be ebbs and flows. Perhaps the net effect of this will be a movement towards changing things - and, fair enough, no system is perfect and it makes sense to try to fix known flaws. However, it makes more sense to try out proposed changes slowly, carefully and with careful evaluation of their effects before there is wide implementation - including determining if positive effects came from the change or from the highly motivated team that executed the pilot project.

"Progressive" politicians have a long history of implementing their "good ideas," such as, say, communism, without any real-world evaluation. In the case of communism we may never know (within 100 million) how many people died from that effort.

Another refreshing splash from your boundless fountain of creativity -- much appreciated. I agree with your assertion that urbanization drives progressivism, and the corollary that increasing per capita wealth moves people to the left. Much of the world's population lives on the upward-sloping portion of your graphs, so internationally these trends will continue. Brazil's example is encouraging. But I wonder what you think about the implications at the leading edges. To me, the signals appear mixed.

First, a good sign. As your charts show, urbanization is leveling off in the US, Germany and other developed countries as well-educated and left-leaning people move out of blue cities into red territories. Remote work is only one driver. Here in Northern California, de-urbanization is in full swing because nobody raising kids makes enough money to buy a house in the Bay Area. Where are people moving? To non-urban Texas and other red areas where jobs are plentiful and nice houses on fair-sized pieces of property on the wildland interface are cheap. Will Texas turn purple any time soon? Haha-- no way. But look at other formerly Confederate states. Over time, re-homogenization is happening, and with it may come a moderation of differences in political points of view.

A more disturbing trend may be happening regarding increasing wealth. In the middle of the rising curve, wealth tends to turn people blue. However, at the extreme, entrepreneurial billionaires seem to be turning right. For every blue George Soros, there appears to be a few Peter Thiels. Now we have entrepreneurial genius Elon Musk, who Tim Church (creator of the brilliant blog Wait But Why -- I know you're a fan) once called "the raddest person in the world" retweeting hard-right conspiracy theories about the recent attack on Nancy Peliosi's husband. He seems bent on reopening Twitter to right-wing bloviators, probably including the former president. Even though he's taking Twitter private, thankfully he won't escape the moderating influence of his advertisers. Corporations seem to have developed consciences -- who'd have thought? I won't get into Rupert Murdoch, whom I think may disprove your theory that individuals don't determine history -- even 100 years from now, Western civilization will be irrevocably marked by his successful attempt to impose his political views on a vulnerable and unsuspecting -- and, remarkably, still unconscious -- viewership that eagerly laps up whatever his commentators choose to feed them. It's a solidly anti-progressive, anti-diverse, anti-democratic diet, and it's just as popular as Coke and fries.

I know you're thinking about where present-day trends may head in the future, particularly in leading-edge countries where free expression of ideas is still supported -- so far. Yes, I agree that in the long term, freedom will win out. In fact, there is an underground spiritual revolution already taking place that will power this cultural transition -- but that's a different discussion. In the meantime, there's some big, dark money working to reverse these positive trends.