The Global Chessboard

History Moves to the Cloud, Part 2.0

A few weeks ago, in Geography Is the Chessboard of History, we discovered a few ways Geography determines a lot about History. Since then, I’ve done a deep dive on Switzerland, and on Spain, France, and Germany. Today, we’re going global: we’ll first have a look at the US, and from there we’ll expand to global influences of Geography on History. The premium article this week will go one level deeper, explaining where Geography comes from (hint: space!).

I hope you enjoy!

US, the Inevitable Empire1

Armed with what we now know about the impact of Geography on History, we can look at a map of the continuous US and realize how unbelievably lucky it is. Take the time to look at it and make guesses on how this drives its luck.

That luck can be summarized with two maps:

First, the US is fortunate to have mountains and oceans everywhere for defense. And where it doesn’t have those features, it’s way too cold for a powerful neighbor to emerge. Canadians are nice anyways. So the US doesn’t need to worry about its physical integrity or waste huge sums on a military race with its neighbors. It’s safe, and that’s more than most countries can say.

The second piece of luck it has is this:

The US’ Mississippi basin:

Has mountain ranges on both sides, which concentrate water inwards.

Has over one million square miles (2.5M km) of extremely well-irrigated land

Is nearly flat, which is also great for agriculture, but also for building anything for cheap, really.

Thanks to these two factors, it’s the world's largest contiguous piece of farmland, producing a prodigious amount of food. Food and any other goods produced there can then cheaply and quickly be transported to the rest of the country—and the world—on its rivers and through New Orleans.

Then on top of these advantages, there’s a thing called “intracoastal waterway”: boats can travel from Boston to Mexico barely sailing through the sea. They can instead do so protected by chains of islands that cover nearly all of the US’ Atlantic coast.

This is what it looks like when you zoom into one of these intracoastal waterways:

Between the Mississippi rivers and the intracoastal waterways, they amount to more internal navigable waterways than the rest of the world combined! What?!

What’s the big deal with all these waterways? This:

So yeah: this means lots of great land to produce lots of food and other goods for cheap, which you can trade anywhere cheaply and fast, all of it protected by formidable physical barriers.

In the roulette of geographies, the US won the jackpot. Whoever held that land would become a world power. It was the inevitable empire.

Makes you wonder though: Why, then, did Europeans conquer America, and not the other way around? Why didn’t America develop civilizations that could compete with Europeans a few centuries ago? Why, in fact, did civilizations from the European continent conquer nearly all of the rest of the world at some point? Why aren’t there different countries on the coasts, protected by the mountains from the Mississippian heartland?

World History: Resources and Competition

Jared Diamond’s Guns, Germs and Steel2 made a simple case for this: When there’s a combination of resources and competition, civilizations develop much faster.

It turns out that the land which spreads from Ireland, Portugal and Morocco on one side, all the way to China, Korea and Japan on the other side, has quite a lot of fertile land, and enough variation in geography that lots of different animals and plants could emerge in different places.

In that path, there are deserts, jungles, and mountains. That isolated many places, such as Egypt, Mesopotamia, the Indus Valley, and China, enabling civilizations to emerge independently there. Every single one of these emerged around very powerful rivers: the Nile, the Tigris and Euphrates, the Indus Valley (and the Ganges), and the Yellow river (and the Yangtze).

In all these places, writing and agriculture appeared and developed locally3, without too much interference (if any) from the others.

However, barriers between them were not too high to prevent any contact. Rice from China could make it to Mesopotamia, and wheat from Mesopotamia could go the other way. This pathway is illustrated by the existence of the Silk Road later on.

So you have all this land to develop diversity, and paths to share it.

All of these areas evolved pretty much the same way: First, they had small bands, then tribes, chiefdoms, and states. The more time passed, the more technology they developed, and the more complex their societies became.

Some of these areas had more formidable barriers than others. For example, both China and India have external barriers that are much more impenetrable than the internal ones. The more time passed, the more they developed, and the more they united.

In contrast, Europe and the Middle East have weaker external barriers but stronger internal ones:

Weaker external barriers meant more access from outside, so there are more serious and constant external threats. That made it easier for external inventions to arrive, and forced European polities to keep up technologically with foreigners.

Bigger internal barriers meant Europe was harder to unify. The result has been a diversity of technologies and approaches to civilization that could challenge each other. However, the barriers were not too high to prevent technology from spreading. More diversity of approaches, together with quick technological diffusion, meant more natural selection of ideas.

A good example of what happens with unity and without competition is Japan: Before the 17th Century, Japan wasn’t united, and it went through one of its fastest-developing periods. But then, it united during the Tokugawa period and remained so between the 17th and 19th centuries. During that time, it didn’t have external threats and, coincidentally, Japan lost the usage of gunpowder, considered ignoble. As soon as Westerners came back and forced Japan’s hand, the Tokugawa era ended, gunpowder was quickly reintroduced, and within 40 years Japan was able to win a war against Russia.

Something very similar happened in China. After inventing the paper and the printing press, and becoming the biggest naval superpower, the country’s influence started dwindling during the Ming period. After the Ming beat the Mongols, they became isolationist. They rebuilt the Great Wall, abandoned the Silk Road, and stopped the voyages of the biggest naval fleet the world had ever seen. They also reduced the power of their civil service, which accounted for a large part of writing, thus minimizing the potential impact of the printing press4.

It might be that in the 1500s, just when European power was exploding thanks to gunpowder, the printing press, and the conquest of America, the competition between all the European states made them progress quickly, while at the time China and India were too big and unchallenged to develop as quickly.

That means History could have easily turned in another direction. In a different world, China might have conquered America, and this newsletter would be in Chinese today. Europe just had the randomness of the right geography at the right time, which nudged History in the direction we know today.

In summary, what this says is that human development is fastest when there’s lots of diversity that can learn from each other and clashes against each other, without one party taking over the whole. In other words, it’s like an efficient market where competitors can learn from each other and take over each other, but only so much, and never becoming a monopoly.

These same forces applied to America and Africa, but Geographically they weren’t as lucky as either Europe or Asia. Why?

The idea is that things can easily spread East-West, because the temperatures and climates are broadly similar, and thus plants, animals and habitats are also the same. If wheat grows in Mesopotamia, it will grow in both China and Europe. Settlements along that axis can trade with each other, share their crops, animals and technologies, and little by little, what appears on one side of the axis ends up on the other side.

This East-West effect is very obvious when you see the record of cities in History. The following map shows which cities are known to have existed by 450 AD5.

This East-West spread isn’t true in North-South axes. With changes in latitude, weather also changes, so plants and animals won’t easily move in that direction6. Without this movement, there’s also less commerce, fewer humans moving along these axes, and less learning being spread.

People, plants and animals coming from Northern Africa would have had to pass the infinite Sahara, then adapt to the Sahel and savanna. As they reached the jungle, not only would they have to adapt to that, too, but also to the very widespread malaria. Then, they would have had to follow the same process in reverse to go to South Africa.

The East-West axes that exist in Subsaharan Africa are much smaller than in Eurasia and North Africa, and much harder to travel to and through. Both the jungle and the Sahara desert make movement really hard. The oceans and Rift Valley stop East-West progression even further.

Many chiefdoms and even proto-states appeared (Ashanti, Mali, Zimbabwe, Songhai…), but they were fewer, less connected, and when they were close to each other, they didn’t have strong natural protections between them. That’s why the biggest African empires were in Northern Africa, which is in the East-West axis of Eurasia and North Africa.

The same thing happened with America.

America has plenty of great places for civilizations to appear. That’s why civilizations appeared independently in both Mesoamerica and South America, and why other civilizations were emerging in other places too, such as the Northwestern Pacific.

But America is structured in a North-South axis. It doesn’t have much width in any specific latitude. Both of its widest points are not the most efficient to develop advanced civilizations from scratch:

North America, what is today the USA, is not very broad compared to Eurasia. On top of that, the Rockies take half the continent. The Mississippi ir oriented North-South across a very vast length.

In South America, what is today Peru-Ecuador-Bolivia-Brazil is also much smaller than Eurasia, and is also split by the Andes and the Amazon Jungle, making spread of technology between them unlikely.

These East-West axes were not good enough for lots of diverse resources and technologies to emerge and share. The North-South axis sits across lots of climates, and on top of that, has huge barriers such as the narrow Central America and the Andes.

By the time Spaniards arrived, Aztecs and Incas were just the most recent heirs of millennia of civilizational development. For example, in Mesoamerica, the Aztecs had been preceded by Olmecs, Toltecs, Teotihuacan, Tarascan, or Mayans farther South. Incas were preceded by Chico, Valdivia, Canari, Chavin, Muisca, Moche, Tiwanaku… Without interference from the Old World, these civilizations would have likely kept developing. Just more slowly, because of Geography.

Coming back to the US, then, why didn’t a civilization emerge there? Well, it did.

The Mississippi was made up of chiefdoms that had agriculture, trade, and big public works, among others. The Northwestern coast of the Pacific had emerging chiefdoms too, built around the wealth from seafood, with commerce, and evolving early signs of agriculture.

What are the most likely explanations of why civilization didn’t evolve there as fast in North America as in Eurasia and North Africa? Or even in Mesoamerica?

If we agree with the East-West vs. North-South axes theory, maybe it’s because North America didn’t have enough interconnected variance: Different people who could master different plants and animals from different areas, that then would be shared, improving everybody’s wealth. Maybe it’s because the river follows a North-South axis, making those who develop in New Orleans unlikely to invade those from the Great Lakes.

Maybe the Mississippi valley was hard to settle from scratch because the river is uncontrollable. Maybe that’s why its settlers built so many mounds, so they could move up during floods.

Maybe sickness contributed, the same way in Central America millions died through germs brought by Westerners—which is also the result of more people more densely settled, living with livestock. Maybe there’s some other reason we (or I!) don’t understand yet.

Regardless of the specifics, what we know is that the same patterns happened across the world over and over again. They were just faster in some places than others, and that was very likely due to the geography, even if we don’t always understand the details.

Takeaways

There you go. This is the quick summary of how Geography has determined so much of History:

Rivers are great for arable land.

Flat plains are great for food.

Large flat plains with lots of water generate lots of food, and hence get lots of people.

Rivers, seas, and plains (in that order) facilitate communication, and hence trade, wealth, and exchanging technologies.

Mountains are bad for building stuff, feeding yourself, communicating, or trading.

They are great for defense though.

Areas with lots of diversity of environments in the same latitude were great to see lots of new technologies emerge and then spread, especially if there were no insurmountable barriers between them.

Conversely, areas with little environmental diversity or where the diversity is in a North-South direction would not develop as fast.

The more isolated an area, the harder it was to get diversity or external threats, and the less it developed.

Some of these rules of how Geography determines History might not be 100% accurate, and I’m missing many more. For example, I barely touched on the inordinate impact that malaria has had on civilization, or how cities tend to be founded on Fall Lines.

The point is not to compile them all. The point is to show how there are factors that substantially influence a lot of our History.

Most of the time, when we study History or we’re told about why things are the way they are, we’re told about wars, generals, and political movements, when in fact much of the time it’s just luck and time that mattered most.

These subconscious misconceptions are problematic, because a huge change is happening: Geography matters less and less. If we don’t understand how much it has impacted us in the past, it’s easy to miss how much the future will change, now that Geography’s role is dwindling.

This is what we’ll discover in the next regular article: how Technology, little by little, has taken over Geography’s role in History. We’ve already started hinting at it, for example, when we compared China or Japan to Europe in the 1500s. We’re going to see much more of that.

Before that, in this week’s premium article, we’re going even deeper into Geography. Because so far I’ve only focused on how Geography determines History. But what determines Geography itself? Why is it the way it is? Surprisingly, nearly all of Geography is determined by one single thing: Astrophysics.

I hope you enjoyed this week’s article! Do you have something to add, or something you disagree with? Let me know! We’re all wrong, all the time—especially me. The only way to get better is by exchanging ideas. And this topic is especially sensitive, but I approach it with humility and curiosity. If I’m wrong, or science has progressed in a direction that I’ve missed, I’d love to hear your thoughts. They’re consistently well put and edifying.

Remote Work

Last week, I explained that the adoption of remote work will depend on what workers want and what companies consider productive. This is the exact same approach that an Economist article took this Sunday. I’m glad to see I drive The Economist’s agenda now7.

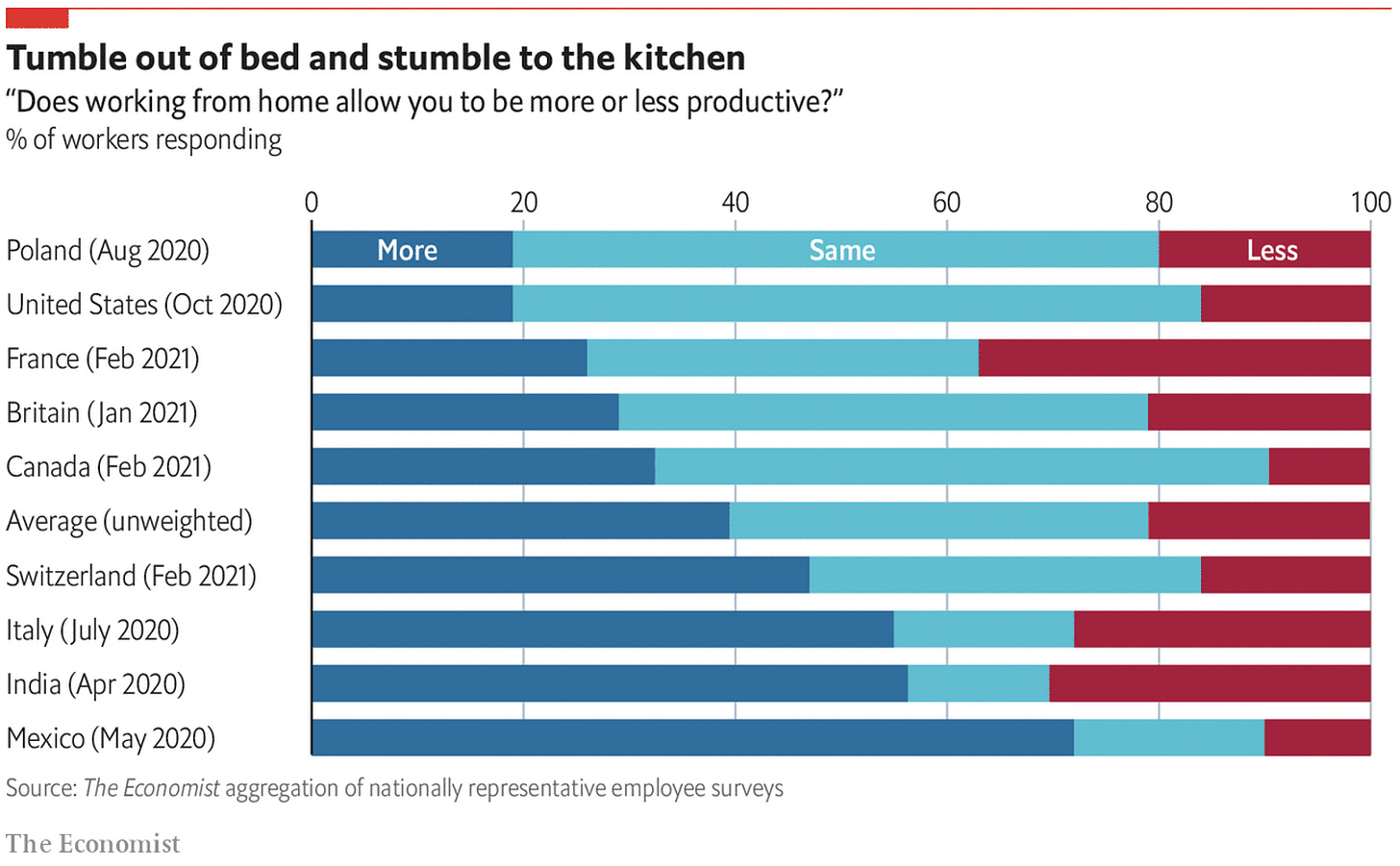

They conclude the same as I do for what people prefer. I had 30% of preference for remote work, and a majority of workers considering they are more productive this way (vs. those who think they’re less).

They find, however, a somewhat different result for what companies think:

Taking Western countries only, and weighing by their population, we get again a reversal with higher productivity remotely than in the office.

With this inconclusive evidence, it’s a good time to remember that we have 1 year of experience with remote work, and it was during a pandemic, compared to hundreds of years of office experience. Remote productivity is likely to go up. Conversely, it also rests on social relationships created in large part before the pandemic.

All of this to say this is hard. But for me, the big takeaway is that for knowledge workers, remote work is unlikely to be much less productive than in office. And since it will be vastly cheaper, it’s likely that companies will use it more and more. The consequences of that in the global economy will be enormous. More on that in a future article.

This is the title of a two-part monographic from Stratfor (the first one is free). It’s very long, but it’s a.m.a.z.i.n.g. Many of the ideas from this series come from these monographics. Another good source to learn about this subject is Prisoners of Geography from Tim Marshall.

I’ve read several criticisms against Guns, Germs, and Steel”. Some people consider the book racist because it suggests that Europeans were meant to conquer other people thanks to their geography. The fear is that it suggests this: “Geography made the settlers of Europe genetically superior, and that’s why they conquered the world”. There’s a history of people who have claimed this since the 19th Century. Google “geographic determinism” if you’re interested. That was not my interpretation of the book, or anything I’ve read since that makes sense, and it is definitely not my view. In fact, most of the evidence points towards the opposite: Humans everywhere, under the same conditions, do the same things. The chessboard nudges History in specific directions. We’ll see this time and again in this series, especially as we start covering technology.

They also appeared and developed in other areas. Both appeared in Mesoamerica, while agriculture alone (without writing) appeared in many more places and at different stages of evolution in many places, such as Papua-New Guinea or the Northern Pacific coast of America.

This is recorded History, not History. But in this case, it goes in the same direction: If a civilization didn’t have the means of recording itself, it was by definition less advanced than the civilizations that could. There’s an interesting counter-example which might come from simply not being able to store the writing, because it was done on a material that didn’t last thousands of years. This has happened. Nevertheless, from all the evidence I could read, this conclusion is still relevant: there isn’t a massive number of cities we’ve missed this way. The trend is still the development across the East-West axis that was welcoming and widest.

“Won’t easily” doesn’t mean “won’t”. It means it will take a much longer time to happen, which means it slows down potential development.

In case it isn’t clear, this is a joke. For those of you not following closely in the back.

"We’re all wrong, all the time—especially me." Perhaps we can rephrase it to "We all have particular perspectives, all the time."

Living in Germany I learnt two years ago from a ranger how disadvantageous the East - West orientation of the Alps is. During the last glacial period the forests North of the Alps lost a lot of their diversity in trees. It got too cold for many tree species and they could not "cross" the Alps and got extinct. In the Rocky Mountains the different tree species moved South when it got colder and then moved North again when it got warmer. Apparently today the variety in trees in North American forest ist about an order of magnitude higher than in North Europe. With the climate becoming warmer and dryer the remaining tree species in Germany are now endangered.

In elementary school I learnt how advantageous the East - West orientation of the first low mountain ranges in Germany is (just South of the North German Plain). During the glacial period a more or less constant wind blew from North to South and carried loess to the South across the North German Plain. The loess stayed at the edge of the plains where the low mountain ranges started, leaving very fertile land.

When humans decided to bring in new crops to Europe they did not follow latitudes (anyway there can be very different climate conditions on the same latitude). The other day I read in John Seymours book "Self-Sufficiency" the potato is originally a tropical plant. It was brought to Europe anyway, not following an East West direction but South North, leading to catastrophic historical incidences. We grow today potatoes in our garden in fertile soil enriched by glacial period loess.

Complex world, my limited personal perspectives. Let us make sure to take lot of different perspectives and develop our ideas further. Tomas, it is very stimulating to follow your perspectives and integrate them. Keep sharing your articles!

I think that the spiritual credence and rational systems plays a huge role in civilization. Philosophical ideas such as monotheism, are definitely an upgrade, from a technology standpoint, because they take on the table the idea of god's transcendence: god lives in "another world" and this world is at men's full disposal. This idea enables the possibility to "use" the world for taking benefits as long as the sea, the mountain, the river, the forest, the animals are not (or not anymore) owned by a susceptible god. That's the reason why, for example, climbing a mountain (reaching a place where life isn't even possible for an hour) is an activity respected in "occidental world" but it would be considered foolishness in Nepal...