You’re a Neuron

Is a flock of sheep just a group of many individual sheep, or something more?

What about schools of fish? (start at 56s. I chose the timings of all these videos so you just need to watch each video for ~10s)

A starling murmuration? (start at 1m33s)

You don’t need to be a vertebrate. What about ants?

And… slime?

This shows slime growing to recreate the Tokyo-area railway system

People are the same (start at 1m25s):

They move like liquids

Which one is a group? Which one is a body? (start at 24s)

The Body and the Cell

What Is an Ant?

You look at each ant like a distinct animal, but they’re definitely not like a dog, a crocodile, or a ladybug. For example, without the queen, the colony dies. Can you consider each ant an individual if they have such dependence on specific individuals?

They live in colonies with millions of other individuals, and most of them are infertile females. They devote their lives not to their own survival and procreation, but to the success of the colony. Is that the behavior of a normal animal, or that of a cell within a body?

One of the reasons why they are so selfless is because many worker ants are clones. If you share the same code as your sister, your genes don’t care whether you’re the one surviving or your sister. That makes that gene very eager to optimize for the survival of the colony instead above the survival of the ant. Just like cells are less important than a body.

How do they reproduce anyway? After spending years developing a colony and increasing its size, it’s big enough to expand. At that point, a swarm of winged ants flies away to mate with members of other colonies and establish new ones. Male ants only appear at that time, and die just afterwards. Put in another way: it’s the colony that reaches sexual maturity after a few years and reproduces, while the individuals behave a bit more like sperm and eggs.

How do ants communicate with each other? They have some sound and touch, but the main communication is through chemical signals. A bit like cells.

Single ants are pretty dumb and weak, but the colony is very resilient and shows complex behavior. The complexity emerges from the interaction between the ants. That interaction is decentralized: there’s not one ant or even a group of ants telling the rest what to do. The complexity emerges from the simple interaction behaviors between the simpler ants.

So you can see an ant as an animal, or you can see it as a cell and the animal is instead the colony. The only difference with you and me is that the colony’s cells are roaming around, while yours are all contained within the body.

Which One Is a Cell?

Cells also coordinate with each other, like neurons firing together (start at 17s)

But cells are not the only ones coordinating with each other. Molecules also do!

Quarks interact with each other to form atoms.

Atoms interact with each other to form molecules.

Molecules interact with each other to form cells.

Cells interact with each other to form bodies.

Bodies interact with each other to form societies.

Societies…

This is fractal. Lower-level elements combine and interact, and from that emerges a more complex behavior at higher levels.

Which begs the question: are you just a body, or also the cell of a body?

You Are a Neuron

How does the brain work?

Neurons connect to each other. A neuron receives incoming information (an input) from others through their dendrites, processes it, and sends a different signal out (the output).

But these traditional renders of neurons don’t do justice to how many connections our neurons really have.

The 100 billion neurons of a brain connect on average to 1,000 other neurons, for a total of 100 trillion connections—each one of them taking an informational input, processing it, and sending an informational output.

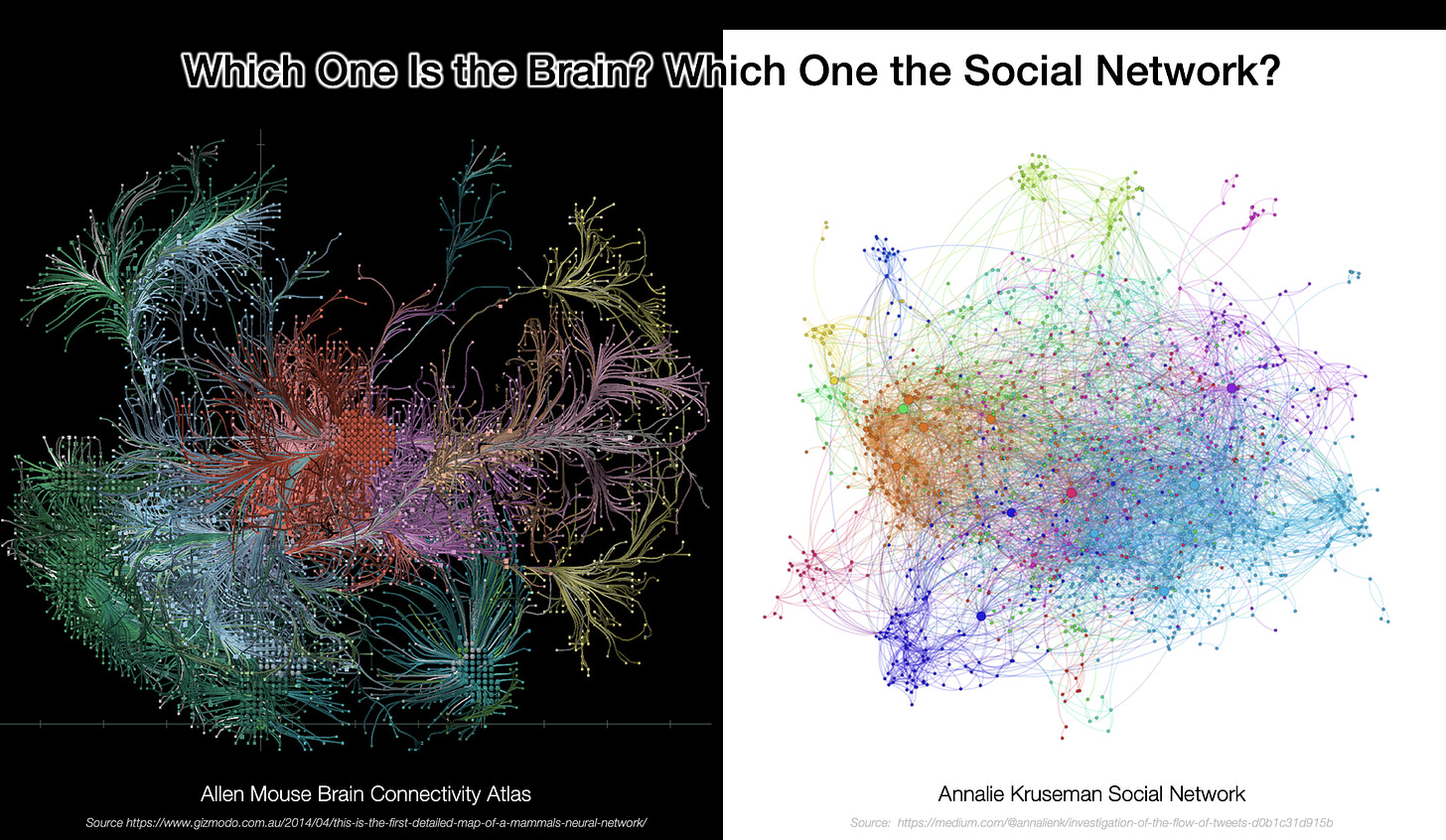

From that perspective, how are we people different from the neurons in a brain?

Think about it. You get information inputs from journalists, from friends, from those you follow, from the websites you visit, the shows you watch, the conversations you participate on… You then process that information, by either thinking or intuition. And you output your own information signal by talking, writing, drawing… Others then go on and consume your output, to form their own thoughts, and create their own output.

We’re not quite 100 billion people. Only 8 billion so far. But it’s just a difference of one order of magnitude. We counter that with more than 1,000 connections: the 150 or so relationships you might have, plus all the other sources of information at your fingertips, coming from thousands or millions of organizations, from newspapers, social media, Google, TV...

This might be why happiness, smoking, and even obesity spread through personal networks: we influence each other the way neurons influence each other. If a friend of a friend of a friend is happier, you will be 6% happier too.

If your main activity in life consists in information management—eg, white-collar workers—you are not only like a neuron in some aspects of your life: you’re a neuron in your entire professional side.

And if you’re a neuron, what is the brain?

The Brains You Belong To

You’re a neuron in several brains. The most obvious is social networks.

You Are Facebook’s Little Neuron

In social networks like Facebook, Twitter, TikTok, LinkedIn, Youtube, or Instagram, we’re all connected to a bunch of other people, consuming information, processing it, responding, reacting.

Some edges (connections between nodes, between neurons, between you and other people) are stronger than others, like the people you follow more closely and with whom you exchange the longest posts. Others are weaker, like the person that appears on your feed every now to post a vacation picture you end up “liking”.

Some neurons are more broadcasters: they have unidirectional connections to millions of other people who listen to what they have to say, but they don’t listen much in return. Others might be the opposite: they follow plenty of people, but don’t never participate, so they don’t influence other neurons much.

For example, during the early COVID times, I acted as a recombining neuron inside social networks: I took the papers from a few dozen people, combined them with my personal experience, and share the output in the form of some Medium articles. These were propagated across social networks until tens of millions of other human-neurons saw them, passing the signal from one neuron to the other.

But in each social network, the spread was different. The design of the network defines deeply how it behaves as a brain. Why does Facebook incite more polarization than TikTok or LinkedIn? It’s the result of their design. Consider TikTok.

TikTok

That company’s incentive is to have you as much time as possible on the app so you watch as many ads as possible so they make lots of money.

For that, they need you to be hyper engaged, so they need to serve you the most engaging content. The best way to serve you the best content is if they pick the best across the entire world. Which means that if something explodes virally on TikTok, it really explodes—they The design of the network creates superstars who by definition will have a massive amount of clout. Superneurons.

This has another impact: culture becomes uniform across the world. What’s successful somewhere tends to be successful everywhere, so you might see a Russian TikTok in Chile. Over time, by sharing the same memes and the same cultural references, they accelerate the uniformization of the world.

But content might also be boring, so TikTok also needs to make it really easy for you to move to the next video, getting a small rush of dopamine: Will the next TikTok be fun?

Like gambling.

So TikTok creates gambling addicts, and that’s how its consumers spend 24h a month on it, more than on Youtube.

More time on site means more potential creators who can win bigger, so the incentive for them to look for new trends is bigger (what is working?), and since the network is global, there’s an acceleration of the cultural evolution on the site.

As a result, TikTok creates a brain that uniformizes neurons at an ever-accelerating speed, creates superbroadcasting neurons, and makes the rest of neurons ever more addicted to interacting with the rest of the brain.

Let’s look at Twitter now.

Twitter

It shows first the tweets from those you follow, and it decays their importance very quickly with time: a tweet from 2 days ago will be buried in somebody’s feed.

That promotes people coming back very frequently so they’re in the know. It also pushes people to post content superfrequently. And that makes Twitter more a real-time network than, say, LinkedIn.

Responses are much more prominent than on TikTok, which invites debate—there’s very little debate on TikTok, so it’s more a broadcasting site. But the debate on Twitter is very linear: all the responses to a tweet are nested into the first tweet, ranked mostly by recency, which doesn’t invite for thoughtful conversation, but rather fast conversation. You can’t have thoughtful and fast conversations at the same time, so conversations on Twitter tend to quickly descend into chaos.

You have 3 ways of getting distribution on Twitter: through more Likes, Retweets, and Responses. Which means that different behaviors are incentivized. For Retweets, you want soundbites that people feel good about endorsing with their own identity. That is great to spur identity politics, for example. Lots of Responses also get your tweet distribution: another way to incentivize debate and polarization. Getting only likes is the weakest of the 3. Meanwhile, Likes don’t get you as much distribution. But Likes are by far the thing that people do most when they want to show compassion, for example. As a result, Twitter fosters more debate and polemic than compassion.

That’s why it is a fast, aggressive, noisy brain. It’s impossible to use this brain for thoughtful debate.

It’s easy to see what happens in social media and conclude: Humans are dumb. We will never agree on anything! But that’s the wrong takeaway. Humans are humans. We’re able of the best and the worst, and most of that is simply defined by the environment. Our brains are the same as those of Homo Sapiens killing each other 50,000 years ago in Africa. What changes is the influences that surround us. We’re neurons in a brain. Change how we’re connected to each other, you’ll change the brain.

You’re a Neuron for your Company

You’re also a neuron for your company whenever you do knowledge work in it.

Each person is a neuron in this brain. You bring information from outside and from inside of the company, process it in your individual work, and communicate it back with your deliverables. In the process, you coordinate with many other neurons—people. Each meeting can be seen as a group of neurons lighting together, exchanging information.

Your dendrites (your sources of information) go to all the people you hang out with or meet. Your work network. Your axones (the channel with information you send out) go to all the people you share information with—which might not always be the same group.

Through these processes emerge the big decisions that companies make: what other companies to buy, what strategy to follow, how to spend their money, who to hire (=what neurons to add to the network), their product design, their marketing…

Seen this way, several takeaways become obvious:

This is why meetings are in fact important. A 1-1 interaction is good, but your time in the week is limited. Every time you have a 1-1, it’s a missed opportunity to have that information shared across the right neurons. If you can have a many-to-many interaction at once, that’s like a group of neurons firing together.

Conversely, meetings are expensive because the entire network is dedicated to firing together instead of exploring other neural pathways.

The bigger a network, the more intelligently it can process information. Quantity (of neurons and connections) has a quality of its own.

But the connection between neurons is even more important than the number of neurons. Children have more neurons than adults, but they’re much less connected. Similarly, a small, well-interconnected team will beat a bigger, poorly connected one.

As a manager, it’s impossible to map out all these relationships. Neural connections are chaotic, like social networks. You shouldn’t try to understand them, to have total legibility. You will fail, and in the process you will change the network in a way that makes it more legible, but barren.

Instead, you should simply foster connection density. Make sure everybody knows other people, expose them to the rest of the group, organize events where people commingle… This is why the “water cooler” was so popular: in pre-remote days, it was a low-cost way of getting these random neural connections. This is why Steve Jobs spent so much time designing the new Apple headquarters. He was shaping the brain.

Each neuron contributes to the brain, but none is necessary. Networks are resilient. If you have a central node where everything passes, you have a very big problem. You need to connect the neurons—people—who are mediated by this intermediary.

The role of a manager is not to understand each one of the neural connections, but rather to look at the patterns in the network, and correct them when they are incomplete. For example, when some teams don’t talk to each other—or when they talk too much—, when a group doesn’t have enough autonomy, when a group of neurons doesn’t have enough knowledge about certain disciplines to process their signals proficiently…

You’re only as good as your data inputs. Employees must have optimal sources of information and processing, else everything down the line is garbage.

Culture is knowledge encoded in the network. Change the links between them, and you change the culture. This is why it’s so very hard to recreate a culture. It’s the emerging result of the complexity of the network.

The quality of every neuron is important, but more important is how the neurons are hooked up to each other.

Put in another way: Organizations are only as productive as their organization, the same way as a school of fish, or an ant colony, or a slime mold, are only as successful as the coordination between them.

So Many More Questions

What about societies? Are they brains, too? If they are, what are the consequences?

What about DAOs—(Distributed Autonomous Organizations)? They try to encode networks more rigidly. Does that reduce emergent complexity?

What about creativity? Where does it reside in a connected network? What’s the connection with synesthesia?

Our bodies don’t optimize for every cell. They optimize for the overall body. Individual cells are dispensable. What does that say about our focus on individual rights? How much do they cost societies overall?

If more neurons and connections make for better processing, are big human societies better?

What does this say about the benefits of centralization vs. decentralization?

What happens with our societies’ brains if we start adding automation?

You are conscious. That consciousness emerges somehow from your brain. If it’s the result of the connection between neurons… Are other things conscious? Is Facebook conscious?

Let’s cover these questions in this week’s premium article.

As always, a very interesting article. Thank you!

However, I have a comment about the type of network that I think has not been

covered in your article.

You do not discuss what I would call the "Hierarchical Network", a system where

the decisions the network takes go in a a "top down" direction. Most companies

follow this approach. In information terms, the data follow one path (in both

directions), but there is another one-directional path of information (orders

or directives) that flows from top management down to lower levels of decision

making.An army is an extreme example of a hierarchical organization.

The other important point is that in a meeting of several people in a room, the

quantity of information that can be exchanged is somehow limited by what in

computing terms may be called the "bandwith" of our speech processes and

inforrmation processing. For conversations where every person can exchange a

meaningful amount of information whith everyone else, the group is limited to

about 10 to 15 people.

The roman army, for example, had their troops divided into groups of ten, with

a Decurion in charge, who in turn formed part of a group of ten Decurions

coordinated by a Centurion, etc.

In many companies there is a board of around 10 people, and countries are

governed in general by a Cabinet of 10 to 15 Ministers. The Ministries are then

subdivided into working units, perhaps not down to the lowest level, but most

organizations follow this hierarchical model.

In a very simplified analysis, taking 10 people in each level (sort of like the

Roman Army), a General (Manager, Prime minister, etc.) commanding 1,000 troops

is three levels removed from a soldier (ten Centurions, 100 Decurions, 1000

common soldiers). We have in this way 4 levels for a big company with 10,000

employees, and 6 or 7 for countries with populations in the millions. We

therefore have a pyramid of decision making, from tactical problems of detail

in the lower levels to the larger, strategy decisions at the top. In a decision process it is a problem, since the different levels tend to move in restricted circles, as far as meaningful information is concerned. Status and wealth also play an important part, so the problems faced by the common folk are not well understood by the leaders. Of course, the more hierarchical

the organization, the problem of asymmetric decision making and information

sharing becomes worse. The king is not so responsive to the lower levels as the

politician and the General can make decisions even disregarding the lives of his soldiers.

Less meaningful information can be exchanged in larger groups. Assemblies of

Citizens, as in ancient Greek City States or Swiss villages can be of several hundred or even thousands, but again the speakers to the assembly are restricted to a few., and the rest are more passive, until, as is ussually done, the decision is taken by a vote. Most Parliaments or the Houses in Congress follow this model, and in most there are Comitties of around ten to 15 people who discuss the proposals in detail.

The above is related more to decision making than to information exchange, and to face to face communication than to the Web, but the "bandwidth" problem of the human brain and speech (or reading speed) remains. In the sharing of information in our networked computer communication, it is true that direct communication with millions is possible, and a few nodes

act as spreaders of information to thousands or millions of receptors. They can talk, but not

really listen to everyone. The exchange of two-way information is still restricted to smaller groups, although hopefully the best ideas will be spread by more people, and the hierarchy effect will be less important in a loose and not hierarchical organization like the WWW. In any case, some hierarchy remains because some outlets are more followed than others.

Of course the above ideas are basically a cartoon of what happens out there, and as the saying goes "God is in the details" but I thought that drawing attention to these limitations of our communication skills as individuals may be worthwhile.

Thanks again for another thought provoking article, abrazo

My guess is you will enjoy a lot Hosftadter's GEB. And probably, also books by his pupil, Melanie Mitchell.