A Brief History of the Caribbean

I recently visited Puerto Rico. As I dove into its geography and history, I fell in a rabbit hole to understand why the Caribbean is the way it is today. It’s fascinating. So please get into this adventure with me! Here’s what you’re going to discover:

Why Mexico’s economy is the way it is.

Why the Caribbean mattered so much to Spain. Hint: It’s not because it was rich.

Why a handful of countries still have colonies there.

Why the US, pretty isolationist in the 19th Century, went to war with Mexico first and Spain later in the Caribbean.

What was the role of the Aztecs in all of that.

What’s the deal with Cuba.

I can’t cover everything, so I left out many aspects. Slavery is a huge one. I will cover it in the premium article later this week, along with new insights, such as why the Caribbean is mostly poor, what can be done about it, what was the role of France, Britain, and the Netherlands in the area, and why one illuminating lens to understand the American South is if we realize it’s a bit like other Caribbean countries.

Within decades after Columbus discovered America, Spain controlled most of it, and kept it for centuries.

But to understand the Caribbean today, you need to start in Mexico.

Mexico’s Silver

So. Many. Mountains.

Bad, right? We said in the past that mountains means no economy. You’re not supposed to be able to build anything on mountains.

“Hold my beer.”—Mexico

What? What is this big light in the middle of the mountains? Mexico City, one of the biggest megapolis in the world—and its neighboring cities. In the middle of the mountains! Wasn’t that impossible?!

"Impossible is Nothing.”—Mexico

Mexico, you’re not supposed to do that. How did you do it?

MEXICO: Ok, ok. Here’s the thing about mountains. They have two distinct problems: elevation and slope. The slope makes cultivation impossible, communication, and trade very hard. However, a high plateau is elevated but flat. If it has water, you can still farm and build cheaply there, even if you can’t easily trade outside the plateau.

I present you the Valley of Mexico.

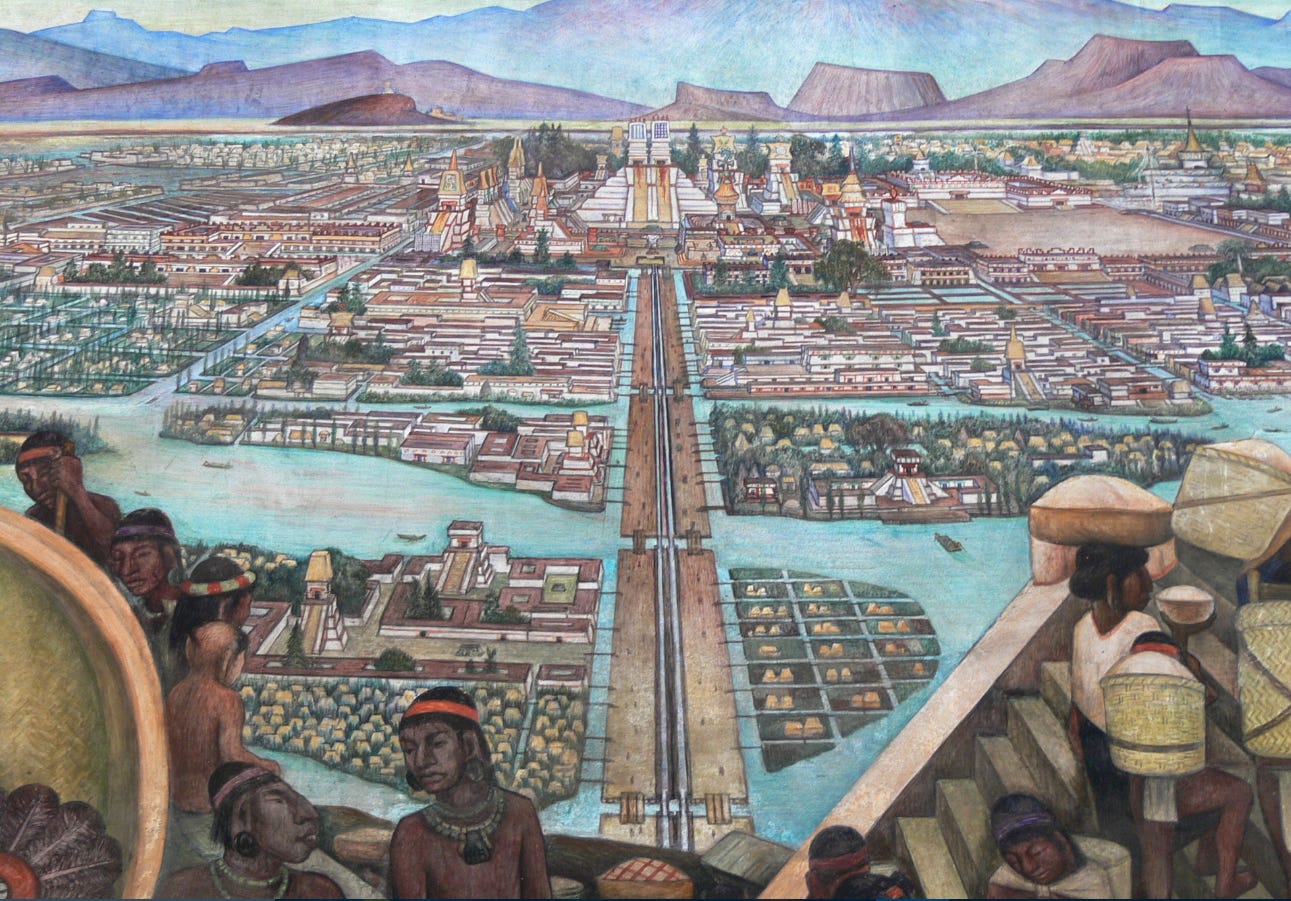

A very flat piece of land, surrounded by mountains. This is what it looked like when the Spaniards arrived to Tenochtitlan, around 1519:

The high plateau concentrates the water flowing from the surrounding mountains, forming a lake. That’s the famous lake on which Tenochtitlan was built.

High plateaus with rivers are both flat and irrigated, which generally means they’re fertile, so they can support intensive irrigation, and a big population. And that’s why Tenochtitlan was among the biggest cities in the world when the Spaniards arrived, and why Mexico City is today one of the biggest megalopolises in the world. And it’s not just Mexico City. The neighboring cities are exactly the same.

A navigable lake meant good local trade, which was great to create wealth in the area. But without a navigable river, the extent of trade was limited to the basin. It was hard and expensive to cross all these mountains. No trade meant less economic activity, and less generation of wealth. When you have lots of people and little trade, you tend to become a poor, populous country.

The Tenochtitlan valley was still amongst the best pieces of land in the area. As the city grew in population, it grew in might, and could subjugate neighboring valleys, reaching all the way to the Caribbean coast.

This is when Hernán Cortés settled what is now Veracruz1.

Cortés built a port in Veracruz. The terrain there is not that great for agriculture, but it was both close to Tenochtitlan and in waters that are as deep as the Mexican Caribbean coast allows.

Veracruz is just 400km away from Mexico City, but there’s a 2km climb in that treacherous path. Without roads or bridges for centuries, the trip had to be done… by mule!

With all these mountains, transport over land was so hard that only very expensive goods could justify the cost of transport from Mexico City to Veracruz, and back to Spain. And that’s why, despite having fertile land, Mexico barely sent crops to Spain. It was mostly silver, and to a lesser extent, gold2.

Mexico produced lots of wheat, corn, sugar, and other crops. But it was all consumed locally. The fertility of the land is why the Mexican population was already large when the Spaniards arrived. It was not economically viable to trade them with Europe, so Mexico kept these crops and its population kept growing over the centuries3.

It’s also a reason why today the populations of Mexico and Central America have a much bigger share of Native Indian descendants than the United States: there were many more to start with, they needed them for mining and local agriculture—and mining—and the Spaniards left them alone in the areas they couldn’t exploit.

Compare that with the US, where the density of population was much lower, and where wealth creation was based on land farming, which benefited from the systematic eradication of locals—at least in the North4.

All of this can be seen to this day in Mexico’s economic development:

Mexico city is on a plateau, same as the neighboring cities of Puebla, Toluca, and Cuernavaca. They all host large populations.

You can see from space, littered with cities, the path of the Camino Real that goes from Mexico to the silver mines in Zacatecas. It continues further north, all the way to the US, but there’s not as much development there—likely because for 300 years it was not economically useful, so there was no reason to settle and develop it. It’s also drier and more mountainous.

The Camino Real from Mexico to Veracruz also has cities throughout.

Acapulco, on the Pacific coast, is where goods from the Philippines arrived to Mexico. They were then also carried by mule to Mexico City, and from there to Veracruz. You can also see Acapulco as the biggest city on the Pacific coast, for the same reason as Veracruz is the biggest one on the Caribbean coast.

But why am I telling you all of this? Isn’t this an article about the Caribbean? Because the function of the Caribbean was to be the gateway of silver from Mexico through Veracruz. The same was true for the silver from Peru, transported through Cartagena de Indias5.

The Caribbean: The Gateway to New Spain

In the 1500s, Spain took control of nearly all of America. But it only cared about extracting wealth. The function of Veracruz and Cartagena de Indias were simple: they were the ports that sent to Spain all the riches extracted from Mexico and Peru.

That made these cities rich—and prime targets for attacks from anybody who wanted that silver. If you’re a pirate—or a competing European power—and you want to get your hands on that wealth, you’re going to attack the weakest points between Veracruz and Spain. If you’re Spain, you want to protect the loot all the way to Spain.

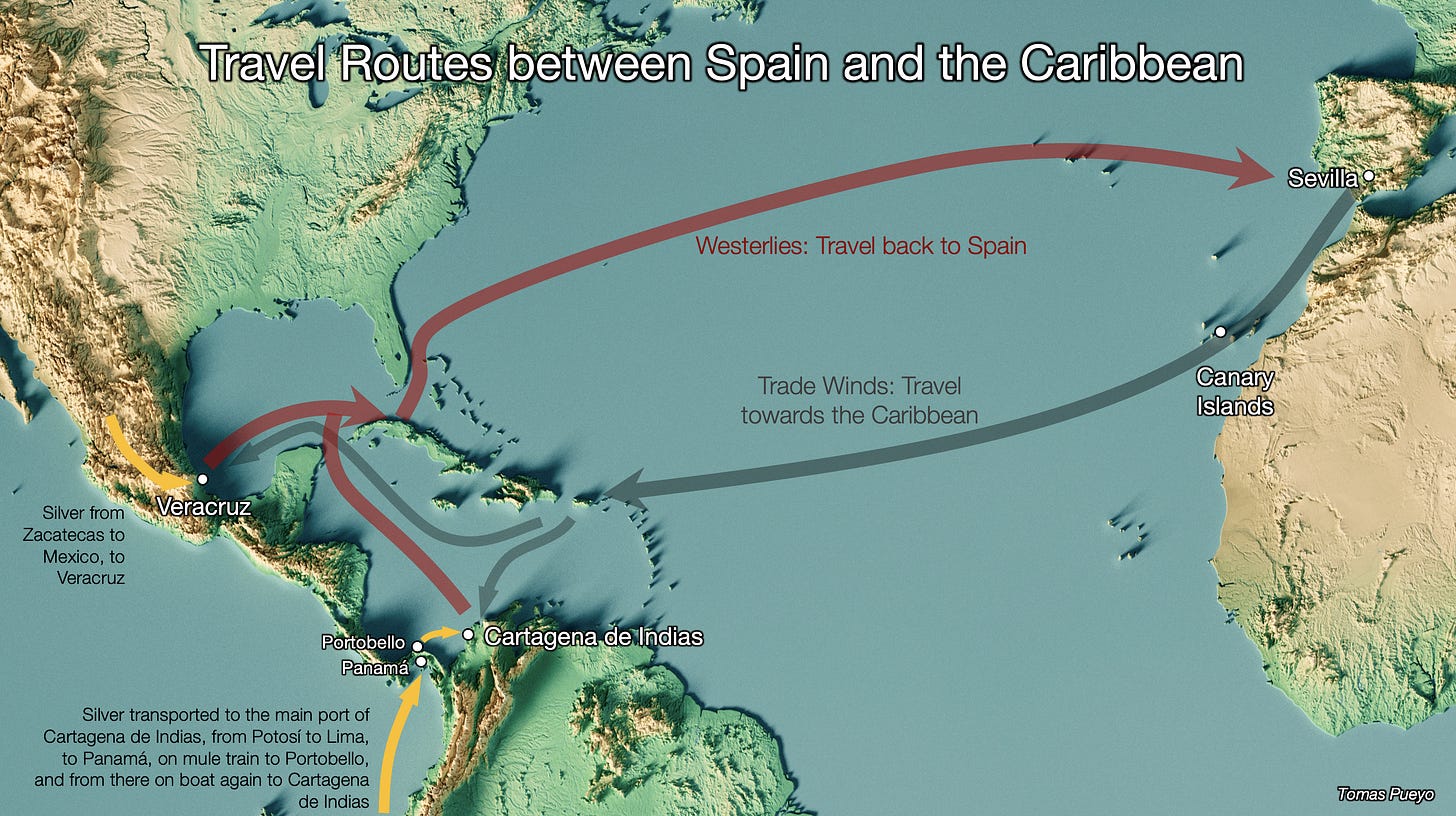

So what was that path of the ships going between Spain and the Caribbean? It depends on the winds.

For the winds to help you get from Spain to the Caribbean, you need to catch the Trade Winds. You need to go South before you go West. The return trip is the opposite: you must go North before you go East.

Fleets going between Spain and the Caribbean needed supplies like food and water, as well as protected harbors to defend them while resupplying. None of the small islands in the Eastern Caribbean (“Lesser Antilles”) can do that: they have no rivers, they don’t have enough land to produce much foodstuff, and it’s harder to build strongly defended harbors there.

The only islands that could do this were the big ones (“Greater Antilles”): Cuba, Hispaniola (today Haiti and the Dominican Republic), Jamaica, and Puerto Rico. They’re not big, but big enough to have rivers, some fertile land, and some harbors easy to protect. That’s why Spain cared about these islands, and why they didn’t care much about the rest of the small islands.

Given the winds, ships leaving Spain would arrive closer to Puerto Rico and leave closer to Cuba. So Spain needed to control at least Puerto Rico and Cuba and have ports there that could supply their fleets arriving from Spain and going back.

Otherwise, other countries could get their hands on one of these islands, threaten Spanish supplies, and use them as settlements to support their own fleets from which to threaten Spain’s hegemony. That’s how you get to this:

Santo Domingo and San Juan de Puerto Rico became the arrival ports for Spanish ships, while Havana was the base where the ships from Veracruz and Cartagena de Indias gathered and resupplied before traveling back to Spain.

Everything the Spanish did was simply focused on getting as much silver from America to Spain. Mexico, Veracruz, Cartagena, Portobello, Panamá, San Juan, Santo Domingo, Havana… All for one single purpose.

Pirates, Privateers, and Rival Nations

The news about American riches soon reached the ears of every sailor and every European capital. As soon as the silver started flowing, they poured in to try to get their share. The next 300 years, between 1500 and 1800, are simply the resulting back and forth between European powers.

Imagine you’re a pirate in the 1500s. You just heard that Spain is transporting massive amounts of gold and silver to Spain. What will you do?

You’re likely to attack Veracruz and Cartagena de Indias. That’s where the riches are awaiting their ships, right? That’s what happened. Then the Spaniards will build up their defenses. You can’t attack as easily anymore.

Where are you going to go next? The Caribbean is big. It’s not easy to intercept Spanish galleons there. But you know they need to go to Europe through Cuba. And conveniently enough, there’s a small passage there: the 80 miles between Florida and Cuba. That’s where you will go. And that’s why most pirates operated in that area, and why they settled close by: in Isla Tortuga, the West of Hispaniola, Jamaica, and the Bahamas.

If you’re Spain, knowing that, you’ll build up your forts. And that’s how you can have things like Fuertes del Morro (which literally means “on the tip”, meaning “on the tip of the natural harbor) in Cartagena de Indias, Santiago de Cuba, San Juan de Puerto Rico, or Havana.

But you’ll also need to start defending your ships on the sea, so you’ll start the Treasure Fleets, convoys that gathered all the ships from Cartagena de Indias and Veracruz, and added a military escort to Spain.

In the 1500s, the threat was mostly pirates. Then, since France was at war with Spain, France started giving licenses to pirates to attack Spanish interests. These privateers6 continued operating for centuries. After France and Spain signed peace treaties, it was the turn of England and Spain to declare war, so British privateers (like Sir Francis Drake) started operating. And then the Dutch, recently independent from Spain, added to the mix.

As time passed, everybody became more professional. Spain built up its defenses. Pirates became privateers. Privateers were replaced by national fleets, and for a couple of centuries they just fought each other to get as much access as possible to Spain’s resources in the Spanish Main (the continent), and, bar that, land that could be used for plantations of sugar and tobacco.

Since Spain was just one country—with a pretty poor geography—it was just a matter of time for the British, French, and Dutch would encroach more and more in the Caribbean. At some point, even the Danish and Swedish wanted in7.

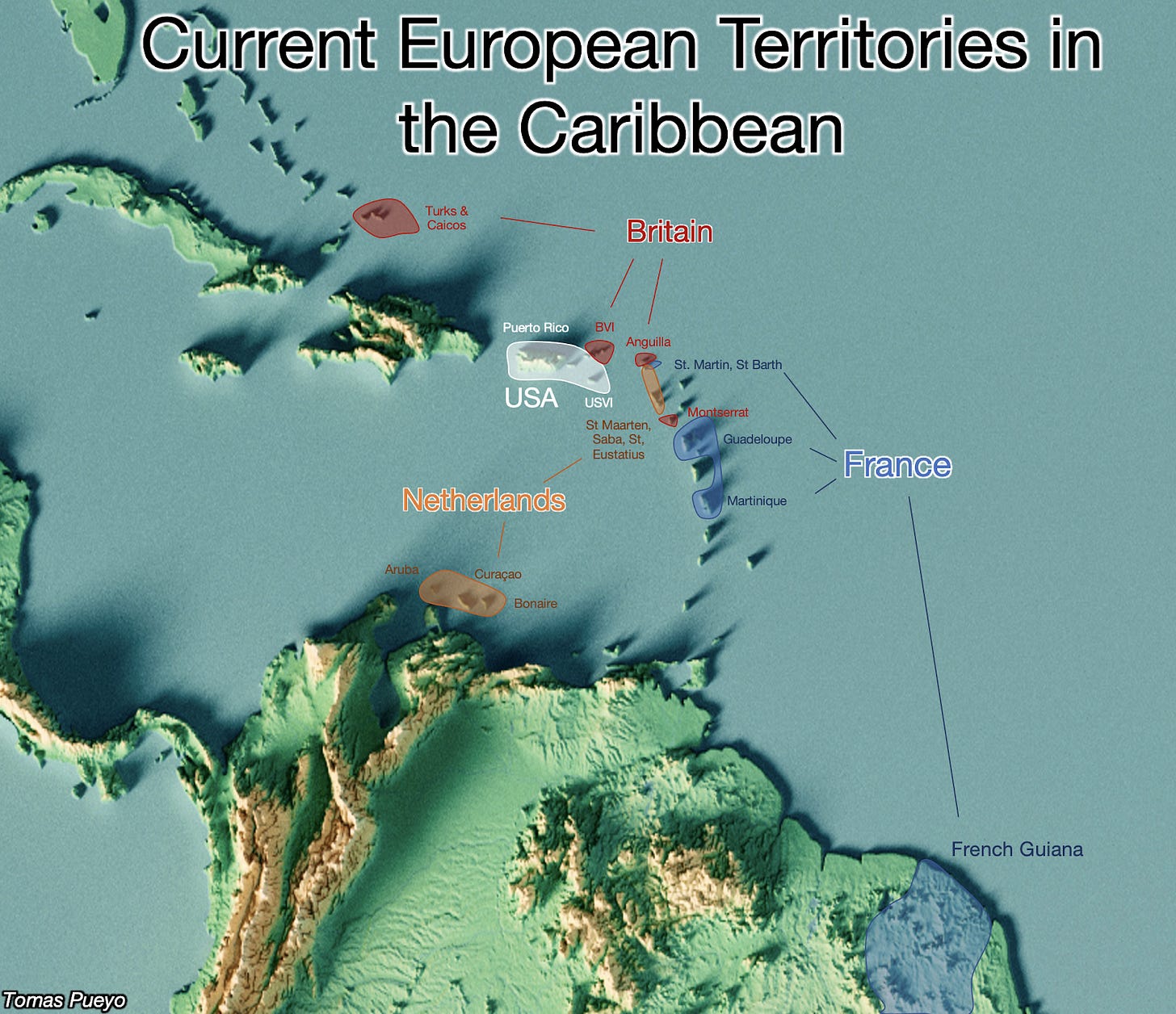

Since Spain mostly cared about Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico because of silver, France, Britain, and the Netherlands focused on the rest. And that’s why the big islands speak Spanish today, while none of the small ones do8. Instead, they all speak English, French, or Dutch, depending on which country controlled them the longest.

From the perspective of those with the guns—the Europeans—, the number one role of the Caribbean was not to generate wealth. Most islands are small and don’t have enough resources or good arable land. They can’t support big populations. None of them had mineral wealth. Even the big ones have very limited resources to this day. Their function was to provide bases for European powers to control the sea trade flows. And that’s what they did for 400 years: They were the chessboard for war games of European powers fighting each other off to figure out who can plunder the most.

As time passed, however, tropical crops became more and more interesting. Sugarcane and tobacco (and other goods such as coffee or indigo) were expensive enough in Europe, and grew well enough in the Caribbean, that Europeans started plantations in the Caribbean to exploit them, even if that was a distant second goal compared to the continental silver. Those plantations, and not the silver, are what drove the African slavery trade in the region9. That’s why there’s so few black people in the Spanish Main (the continental piece): slavery was not as widespread there, and where it was, the Spaniards used the populous natives. But in the smaller islands, there were few natives to begin with given the local resources available, and most died of diseases and oppression. They were replaced by Africans.

American Independence Days

That all ended in the 19th Century.

Nationalism started developing in Europe in the 1500s, mainly thanks to the printing press10, strengthening countries like France, England, or Spain, and creating new ones like the Netherlands. Other nations took longer to emerge, like Italy and Germany, which were only born at the end of the 19th Century.

Something similar happened in America. Over the centuries, nationalist ideas started emerging. They were coupled in the 1700s with Enlightenment ideas, including human rights and self-determination. That’s why the United States declared their independence in 1776, and not 1676, and why those who pushed for independence were nearly universally wealthy and literate—if you couldn’t read, you couldn’t easily access these ideas.

The same was true in the rest of America. Nationalist sentiment grew over the centuries. It combined with enlightenment ideas in the 1700s, and reached critical mass at the beginning of the 1800s.

At the turn of the century, Europe was marred by the Napoleonic wars. With fewer resources and little attention from France, and a huge enslaved population, Haiti was the first country to declare its independence through the first successful slave uprising.

When France took over Spain in 1808, Mexico, Colombia, Venezuela, Chile and Paraguay took advantage of the situation to declare their independence around 1810. Within 10 years, Peru, Argentina, Honduras, Nicaragua, Guatemala, El Salvador, Costa Rica and Ecuador also declared their independence from Spain.

The Relay

By 1825, Spain only had Cuba and Puerto Rico left in the Caribbean. But as we saw before, their main value was not their crops, but as a gate for the riches of the Spanish Main.

Now that the trade from Mexico and Colombia stopped, Veracruz and Cartagena de Indias started declining, and Cuba and Puerto Rico had lost their usefulness. Cuba had some fertile land, but it was never cultivated for plantations at a massive scale the way Hispaniola was. Puerto Rico had a bad geography for plantations. These islands weren’t as economically viable anymore.

Without the riches from America and rife with internal conflict, Spain had fewer incentives and a lower ability to keep Cuba and Puerto Rico.

But another power did have both incentives and ability.

We saw in The Global Chessboard that the US’ most important asset is the Mississippi basin. Well, for it to really make the most of it, it needed to control the basin all the way to New Orleans, and from there the exit of the Caribbean sea to the Atlantic Ocean. The US had three problems to achieve that.

The first problem is that in 1800 the Mississippi basin was French. So the US bought it from France as soon as it could—during the Napoleonic wars.

The second problem was that, after its independence, Mexico was awfully close to New Orleans. And it only had one good port, Veracruz. Taking over New Orleans would have been tempting. The US needed a buffer zone. So it incentivized settlers to go to Texas, then fostered a revolution, creating the independent state of Texas, and then annexed it. That’s why the US and Mexico fought a war between 1846 and 184811.

The third and last problem was Cuba. The same way as Spain had needed it to control shipments from the Caribbean’s Veracruz and Cartagena de Indias, now the US needed Cuba to control shipments from New Orleans.

The US knew it needed it since the beginning of the 1800s12. It tried to buy Cuba on several occasions. Finally, after years of a weakening Spain and a stronger independence movement, it entered into war with Spain, and took over Cuba and Puerto Rico in 189813.

Cuba became independent, but the US made sure it controlled it. Its constitution allowed the US to intervene in Cuba if its interests were threatened. That’s also when Guantanamo Bay becomes American.

This is also why the US became so jittery when Cuba became communist. It’s not just that it threatened communism in the US. It’s also because it threatened the viability of the entire Mississippi heartland.

Hiding the Lesser Antilles

What about the smaller islands in the east? Just as few cared about them during the previous centuries, few still cared about them in the 1800s. They were small, not very productive beyond some plantations, and didn’t have enough population to threaten uprisings or even strong nationalist movements.

So while countries were becoming independent left and right, including some islands, the European owners—Great Britain, France, the Netherlands and Denmark—kept it as low key as they could with their small islands. When somebody asked them: “What’s up with these colonies?” they responded “They are not colonies. They are overseas territories.”

And that’s how, to this day, a bunch of Caribbean islands are controlled by the most powerful European countries with access to the Atlantic, and why none of them are Spanish14.

It’s also why most of the Caribbean is poor: it has few natural resources and it’s far away from everything, now that it’s not a gateway to anything, so trade costs are high. The richest countries in the area either have oil, tourism, tax havens, or a combination of these. And yet none of them is very rich.

Takeaways

Mexico has lots of mountains, which is bad for its economy.

Its population is concentrated in fertile high plateaus, which means lots of food but high trade costs, making it hard to accumulate wealth.

Veracruz was the main port for centuries, because its role was to transport mostly the silver from the Zacatecas region, transported through Mexico City. You can still see that path to this day.

The same was true for the Bolivian silver through Lima, Panama, Portobello, and Cartagena de Indias. That’s why Veracruz and Cartagena were so rich, and why they aren’t as much today, now that they are not the centers of silver trade.

The role of the Caribbean for Spain was to facilitate the trade of that silver. For that, the big islands were the most useful: Cuba, Hispaniola, and Puerto Rico.

Pirates appeared to steal that (plundered) wealth. They were replaced over time by European powers who fought it off for centuries.

Since the smaller islands didn’t serve as gateways of silver wealth, few cared about them, and European powers tried to conquer as many as they could while Spain was focused on the Spanish Main and the big islands.

In the 19th Century, with independence movements in America and Napoleonic wars in Europe, all the Spanish Main declared its independence.

Cuba and Puerto Rico were not as useful anymore to Spain, as they were the gateway to nothing for them. But they were the gateway to the US for Mississippi trade. That’s why the US took over Cuba and Puerto Rico.

It’s also why the US fostered Texas independence, and then annexed it.

While Cuba eventually declared its independence, Puerto Rico never did. Some islands in the Caribbean also declared their independence through the 19th and 20th Centuries, but European countries kept as many as they could, to this day. And since they were small and poor, few cared, so they got away with it.

The premium article this week will cover plantations and slave trade, the role of oil, why Mexico City is polluted and sinking, and why it’s the same in other cities around the world. I’ll also quickly cover the lessons all of this gives us for space exploration, which is something I’ve started paying attention to thanks to one of you who reached out to me. If you have thoughts, comments, or interesting topics you want to share with me, feel free to!

The indigenous people there were pissed at the Aztecs, who were requiring another payment in slaves and sacrifices. That’s why they allied with the Spaniards to beat the Aztecs—an alliance that would prove the end of the Aztecs. But also a boon for the local Indians, who survive to this day.

There were some other goods, coming from the Philippines and through Acapulco, but I’ll cover those in the premium article. There were also red dyes from Mexico and blue dyes from Guatemala. All of these were minor compared to silver.

After the initial collapse due to illnesses imported by the Spaniards.

Writing this gives me shivers. It’s horrible to think how the fate of millions of people’s lives and cultures were determined by economics rooted in geography. But it’s the way the world works. If we don’t understand it, we can’t make it better.

Silver was also discovered in Potosí, Bolivia. After mining, it traveled to Peru, from there on boat to Panama, from there on mule to Portobelo, from there again on boat to Cartagena de Indias, and from there to Spain. That made Cartagena de Indias and Veracruz quite similar in terms of cities and function in the Caribbean.

In French they were called “Corsaires” because they had a “Lettre de Course” to allow them to operate.

They conquered the islands that the US would later buy to form the US Virgin Islands.

The only exception being Hispaniola, where the West speaks creole, because France was able to establish itself on the Western side. Spaniards didn’t like it, but they accepted it since they didn’t need the entire island.

This is a huge part of the history of the Caribbean. I want to make it justice, so I’ll cover it more in detail in the premium article this week.

I’ll have a huge chapter on this in an upcoming article.

It also had the benefit for the US South to add a slavery state, which would likely mean two more senators to keep the slavery system alive against the aspiration of the North.

And Southerners were especially interested, for the same reason as with Texas: yet another slavery state to support them against the North.

And Philippines. Basically all of what was left of Spain’s colonies.

Germany, Norway, Iceland, and Ireland didn’t exist during the American colonization period. Sweden tried, but just held to St Martins for a brief period of time. Denmark sold its islands to the US, as the only country feeling ashamed of colonialism. These islands are the US Virgin Islands today. No Mediterranean power could access America since they couldn’t go through the Spanish- and British-controlled Gibraltar Strait.

Thanks for improving my knowledge and understanding of Caribbean history, I think my Australian school teaching on the subject was precisely zero. Thanks also for using more accurate terms such as accumulating wealth or extracting it (a nice way of saying taking it by force). As you say, if we don't understand the way the world works we can't make it better.

Very interesting!

Just 3 remarks:

1. you said "From the perspective of those with the guns—the Europeans—, the number one role of the Caribbean was not to generate wealth. (...) Most islands are small and don’t have enough resources or good arable land. Their function was to provide bases for European powers to control the sea trade flows. (...) As time passed, however, tropical crops became more and more interesting. Sugarcane and tobacco (and other goods such as coffee or indigo) were expensive enough in Europe, and grew well enough in the Caribbean, that Europeans started plantations in the Caribbean to exploit them, even if that was a distant second goal compared to the continental silver."

- Well, a distant goal for the Spaniards indeed, but not for the other Europeans as they didn't really have access to that silver anyway. Consider Barbados for instance which became a very important generator of wealth for England, if not the ultimate one in the Americas :

"Barbados quickly acquired the largest white population of any of the English colonies in the Americas. In many respects, Barbados became the springboard for English colonisation in the Americas, playing a leading role in the settlement of Jamaica and the Carolinas, and sending a constant flow of settlers to other areas throughout the seventeenth and early eighteenth centuries." http://www.bbc.co.uk/history/british/empire_seapower/barbados_01.shtml

"By 1660, Barbados generated more trade than all the other English colonies combined. This remained so until it was eventually surpassed by geographically larger islands like Jamaica in 1713. But even so, the estimated value of the colony of Barbados in 1730–1731 was as much as £5,500,000.[11] Bridgetown, the capital, was one of the three largest cities in English America (the other two being Boston, Massachusetts and Port Royal, Jamaica.)" https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Barbados#Early_history

- We can also consider Haiti : While Napoléon had sold Louisiana to the United States for 15 million francs, "On April 17, 1825, the French king Charles X (...) issued a decree stating France would recognize Haitian independence but only at the price of 150 million francs – or 10 times the amount the U.S. had paid for the Louisiana territory. The sum was meant to compensate the French colonists for their lost revenues from slavery."

-The Elysée Palace, where the French President stays today, was financed by Antoine Crozat, someone who benefited massively from the Slave Trade and Haiti, and became the wealthiest Frenchman by the beginning of the 18th century, he was worth around 20 millions pounds in 1715 (300 billion Euros in today's money)

https://www.franceculture.fr/histoire/lelysee-le-plus-grand-symbole-a-paris-du-passe-esclavagiste-de-la-france

2. You said "That’s why there’s so few black people in the Spanish Main (the continental piece): slavery was not as widespread there, and where it was, the Spaniards used the populous natives."

but talking about the continent, maybe you should have said a word about the massive inflows of blacks slaves into then Portugal's Brazil. Today's, around 7% of Brasilians, Ecuadorians and Colombians are black, this proportion reaches 21% in Suriname, almost 30% in Guyana and nearly 14% in the USA. And this is not counting people of mixed ethnicity, which counts for 43.13% of the population of Brazil for instance!

3. In your 14th note, you could have said a word about the Scottish attempt at colonizing the Americas, in particular the ill-fated Darien scheme : "In 1696, 2,500 Scottish settlers, in two expeditions, set out to found a Scottish trading colony at Darién on the isthmus of Panama. These settlers were made up of ex-soldiers, ministers of religion, merchants, sailors and the younger sons of the gentry, to receive 50 to 150 acres (0.61 km2) each. (...) In 1699, (...) the Spanish mounted an expedition of 500 men to wipe out the Scots. This was effective, as most settlers had already succumbed to disease or starvation."

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Scottish_colonization_of_the_Americas#Darien_Scheme_(1695)

Thanks again for your blog !

Thomas Jestin

https://twitter.com/thomasjestin

https://www.thomasjestin.com/