Argentina’s Original Sin

How Geography and Institutions Conspired to Make Argentina Poorer

There are four types of economies: developed, developing, Japan, and Argentina.1

Buenos Aires, 2020s:

Buenos Aires, 1930s:

Last week, we saw how Argentina’s geography is unbelievably good, yet the country is not that rich. Why?

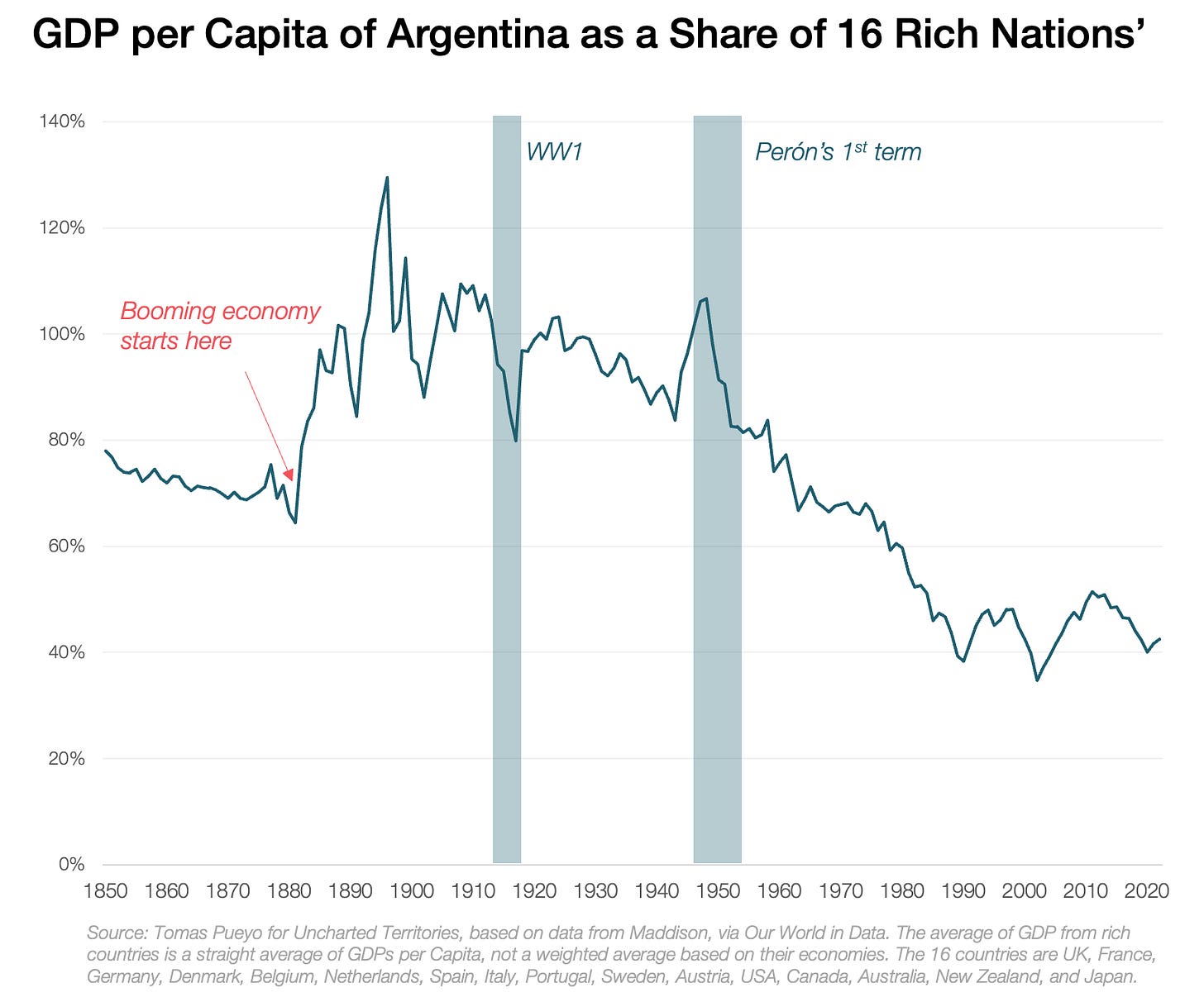

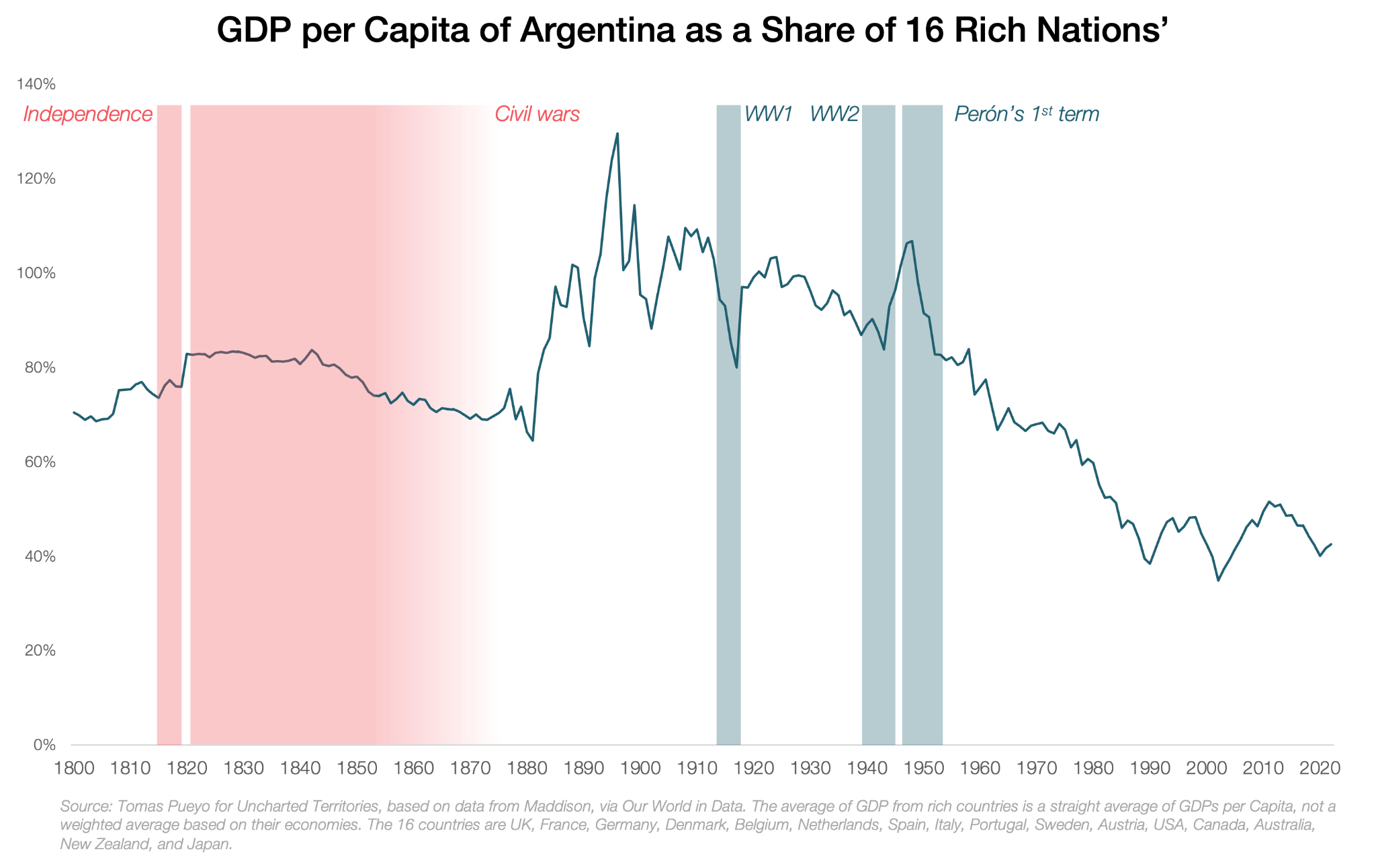

Try asking this question and see the immediate flood of: Perón took power and destroyed our country!

But the timing doesn’t quite work.

Perón had a role, as we will see later, but the roots must run deeper: Compared to the average wealth of developed countries, Argentina peaked in 1896! The country started a continuous decline around WW1. The beginning of the end for Argentina must have hit around then.

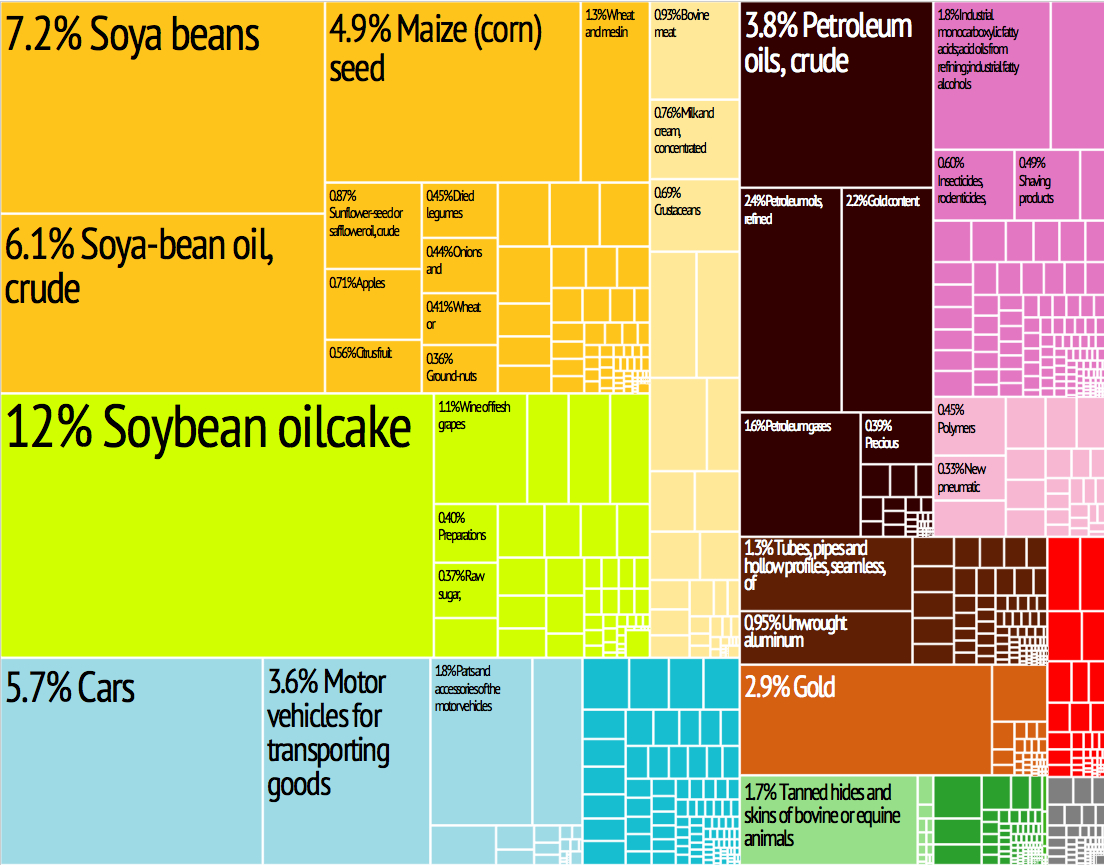

It might help to figure out what made up Argentina’s economy around that time. By the eve of WW1, 35% of Argentina’s GDP came from… agriculture. An additional 22% of GDP came from trade, but 95% of exports were agricultural. In fact, the lion’s share of Argentinian exports is still agriculture.

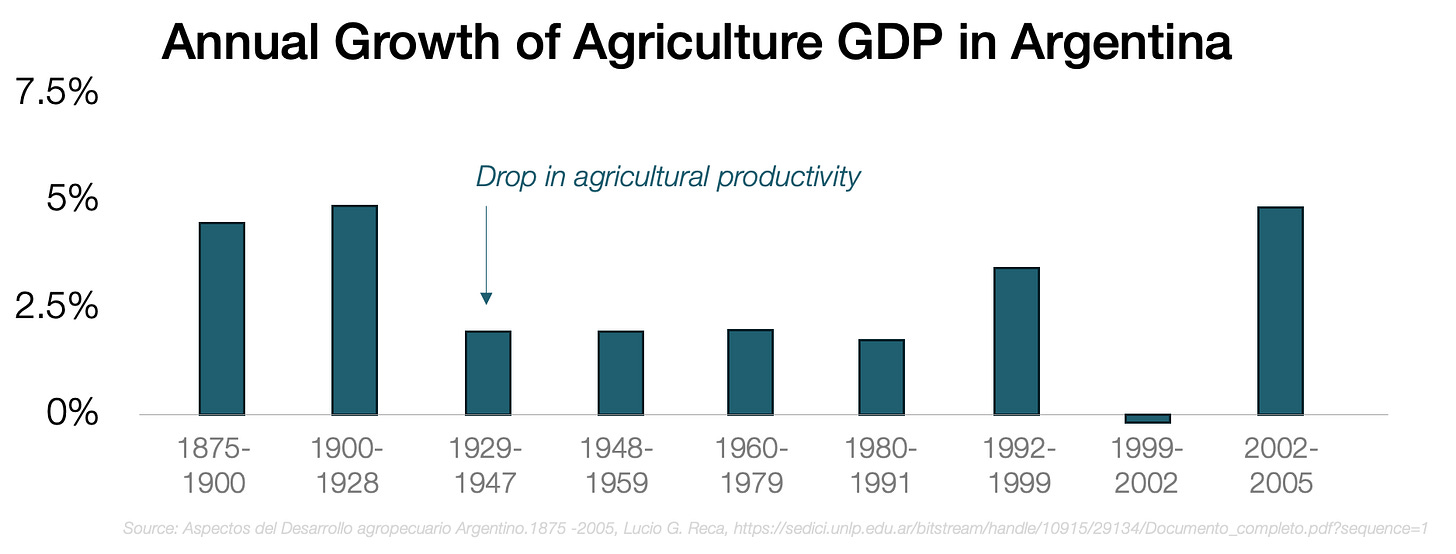

It’s fair, then, to say that most of Argentina’s economy was agricultural during the country’s apogee, so the original problem in Argentina’s economy must be linked to it: Somehow, Argentina’s agricultural productivity slowed down, and the economy never fully moved on from its dependence on it. Why?

The Success of Argentina’s Agriculture

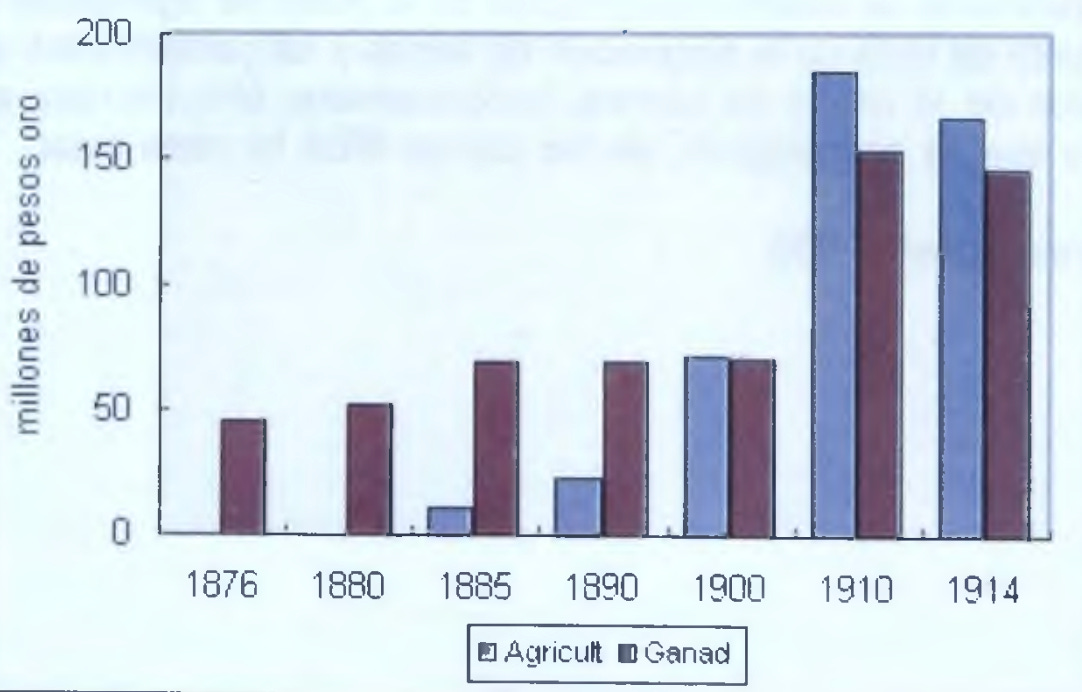

Argentina’s economy went through a massive economic boom starting around 1880.

Compare that with this:

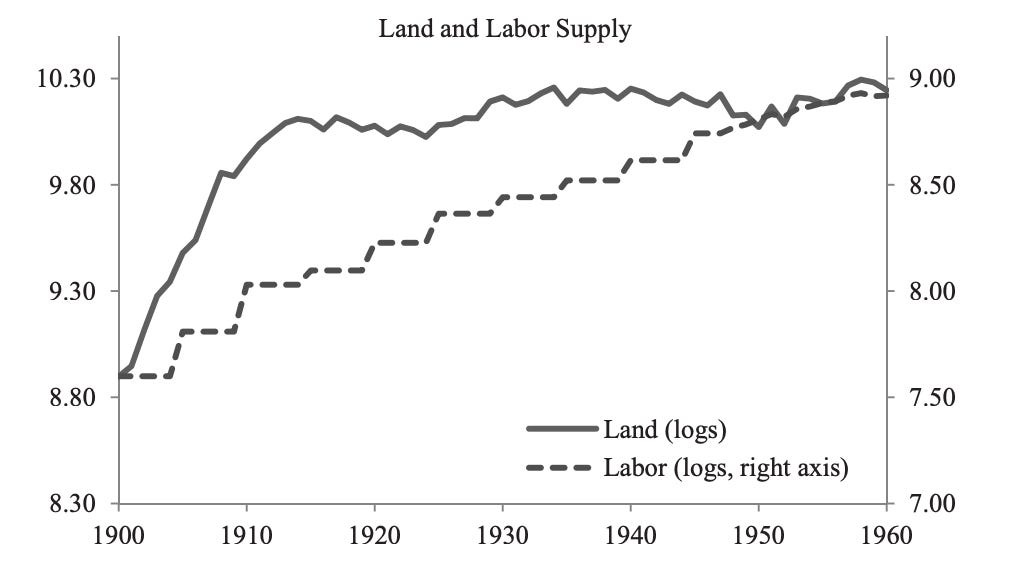

Crop production boomed in the late 1800s: Wheat acreage increased by ~5x between 1890 and 1910.2 93% of the increase in agricultural production until 1930 was due to the addition of new arable land. But that growth decelerated heavily in the early 1900s:

Why? A big factor was land:

So what happened is that, in the late 1800s and early 1900s, there was a massive agricultural boom in Argentina, and people raced to convert new land from pasture into cropland. This lasted until the 1910s, when all the good land was taken.

This growth in cropland until the 1910s was furthered by other factors:

A wave of European immigrants arrived to work the land and the cattle

Landowners bought agricultural machinery

They also sourced genetically superior cattle

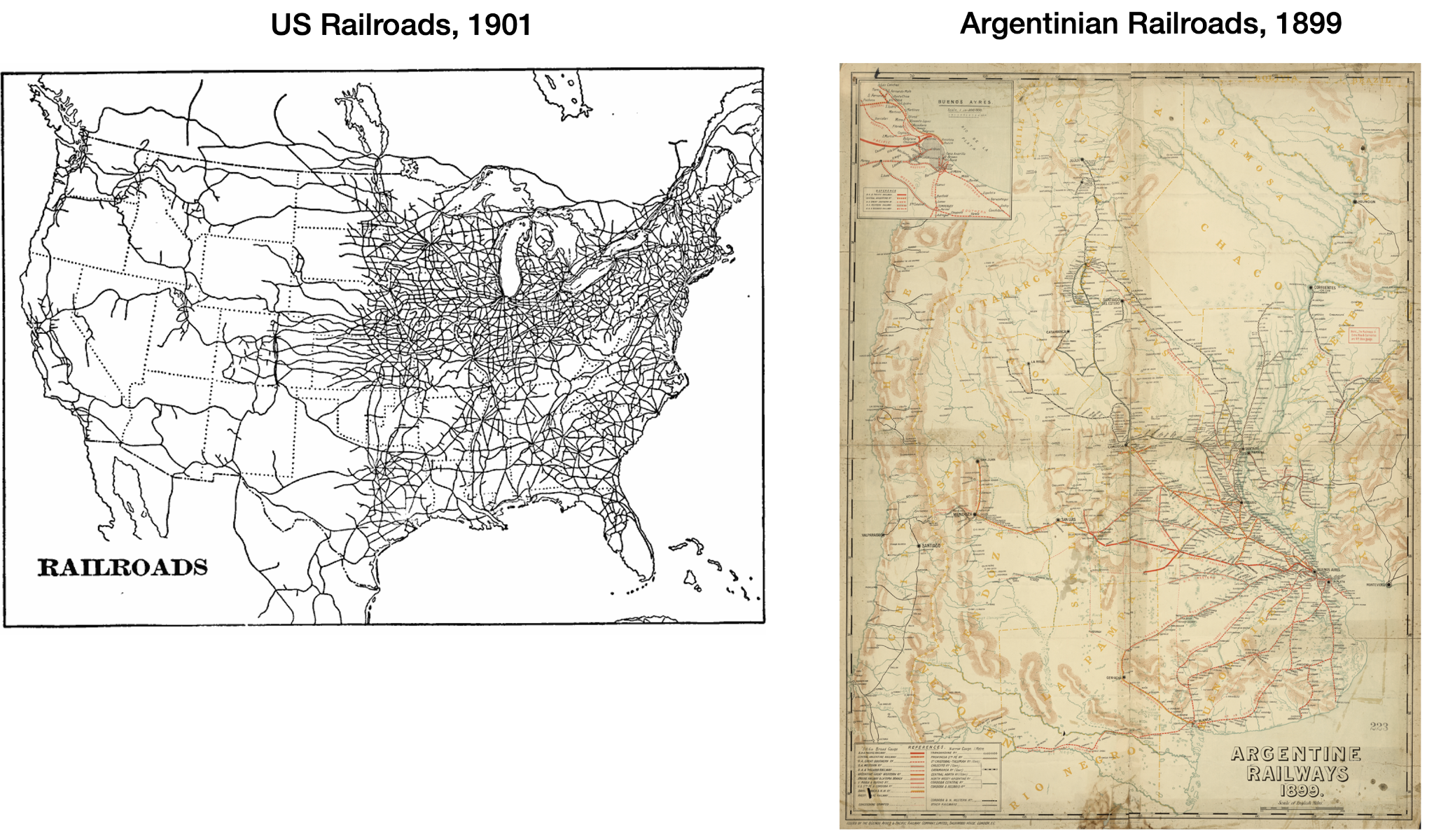

Argentina built its railroads around that time

Refrigeration technology started appearing, after being invented in the 1860s in the US

Steam boats and bigger ships allowed for cheaper transportation of cargo overseas

The combination of these last three reduced the cost of transportation from ~40% in the 1880s to ~10% before WW1.

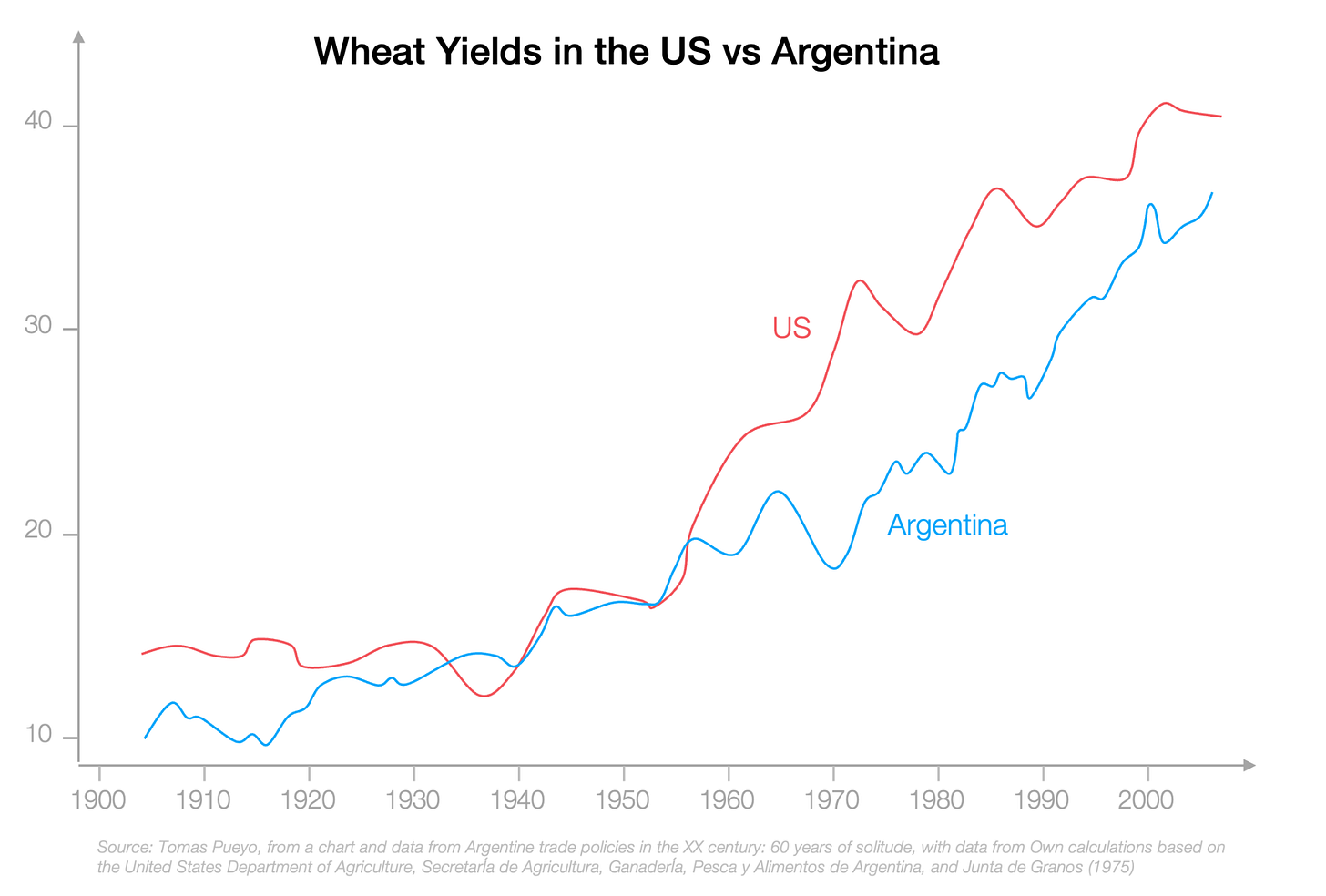

So more farmers with better machinery produced more crops, while better cattle produced more meat, leather, and wool, all of which could now be transported more cheaply to Buenos Aires, and from there to the world. On the eve of WW1, Argentina’s exports per capita were 2x those of the US! By the 1920s, these developments rendered Argentina’s agricultural yields similar to those in the US.

Dig a bit deeper, though, and differences between the US and Argentina become apparent:

Why were Argentinian crop yields lower than the US’s until the early 1900s?

By the time Argentina started planting crops, the US had been doing it for centuries in the East Coast and in the Midwest. Why so late in Argentina?

Argentina had a much longer tradition of ranching than farming. Why?

I mentioned that Argentina started building its railroads in the late 1800s. By then, the US was already criss-crossed with railroads. Why the disparity?

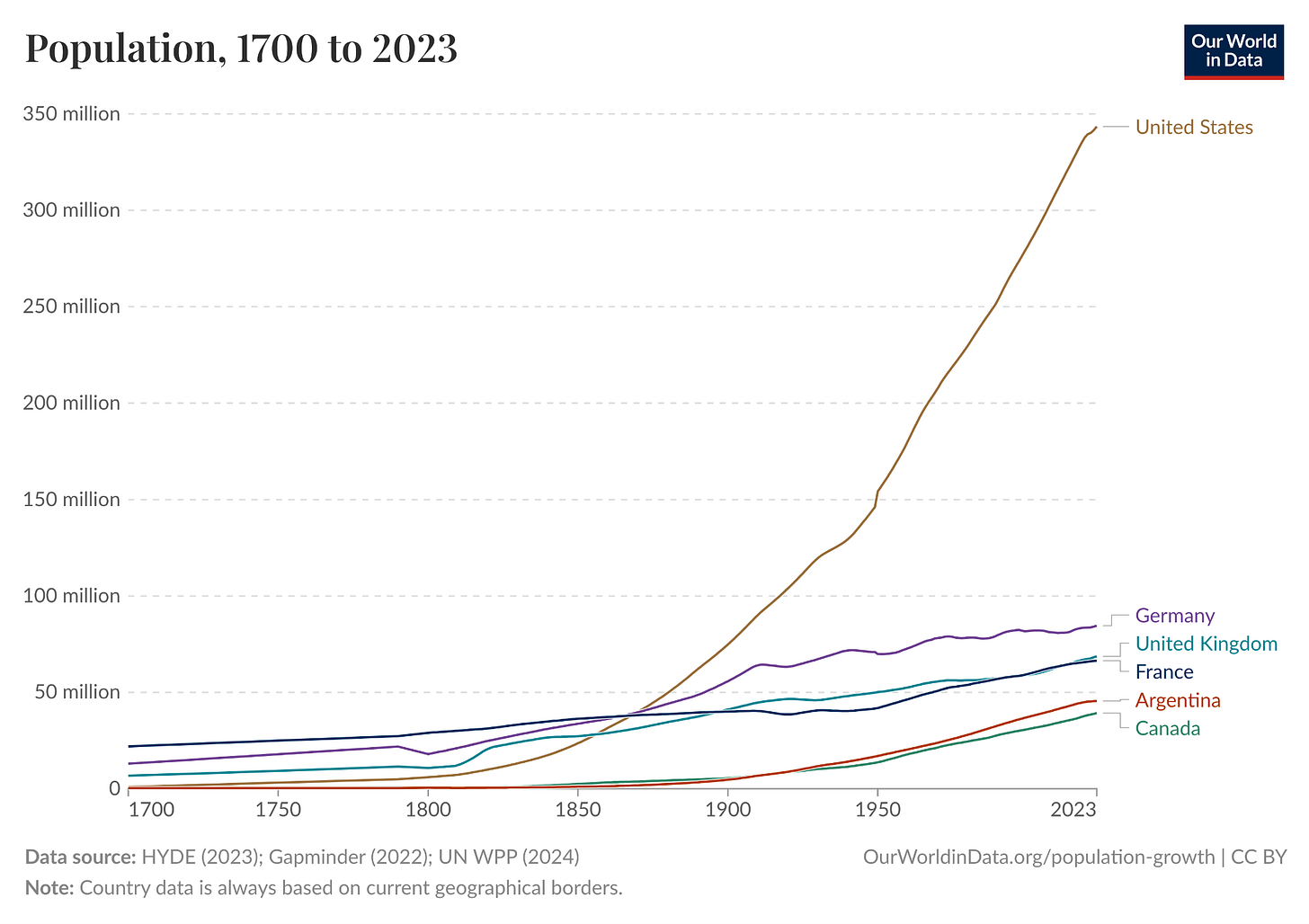

The US’s population had been growing dramatically for over a century by the time Argentina’s started growing. Why?

Argentina’s agricultural land was more concentrated than in the US. Why?

The US was in full Industrial Revolution by the late 1800s, when Argentina was still agrarian. Why?

Answering these questions will get us closer to understanding why Argentina is poorer today than it could have been.

The Grass Ceiling

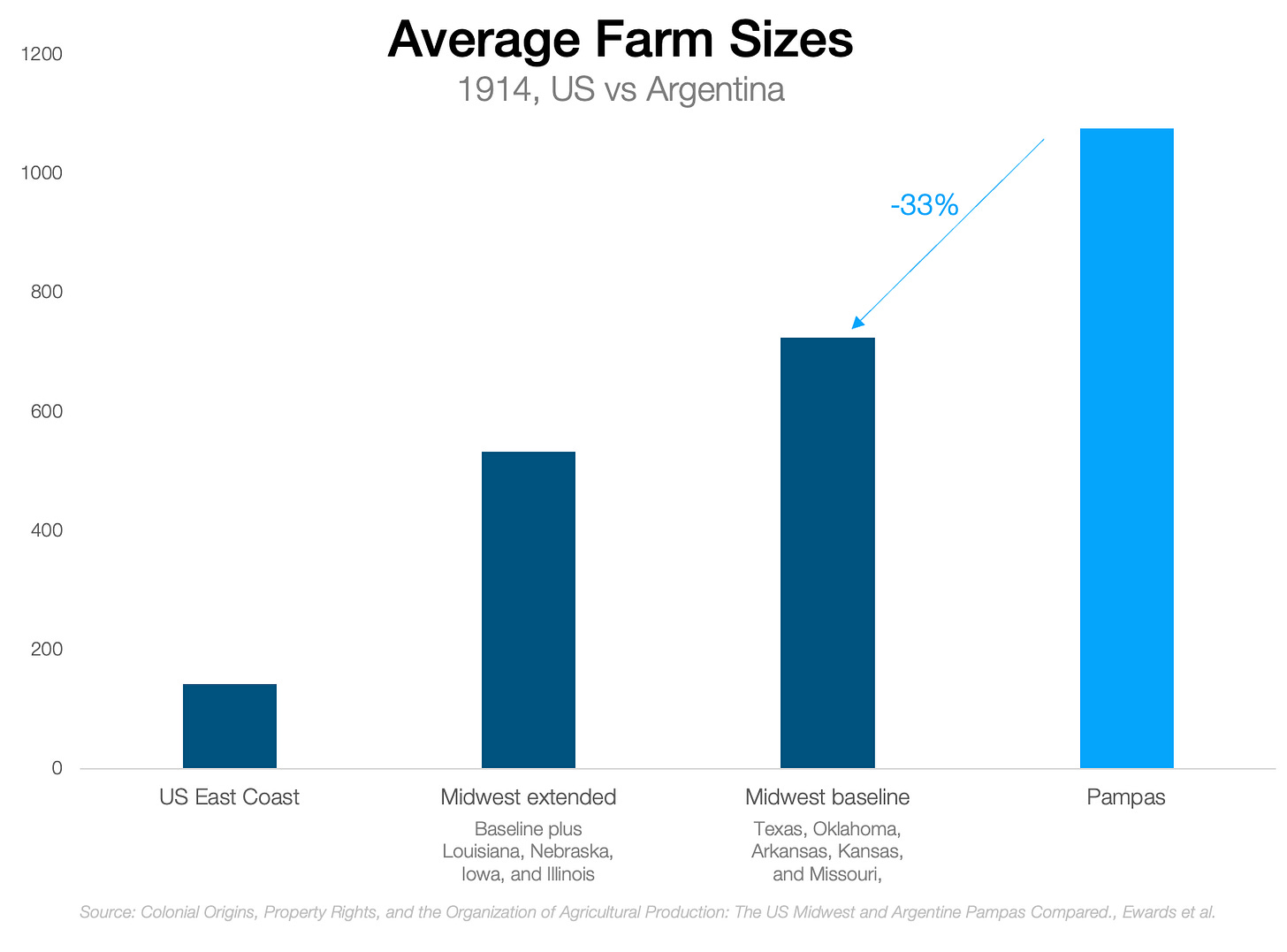

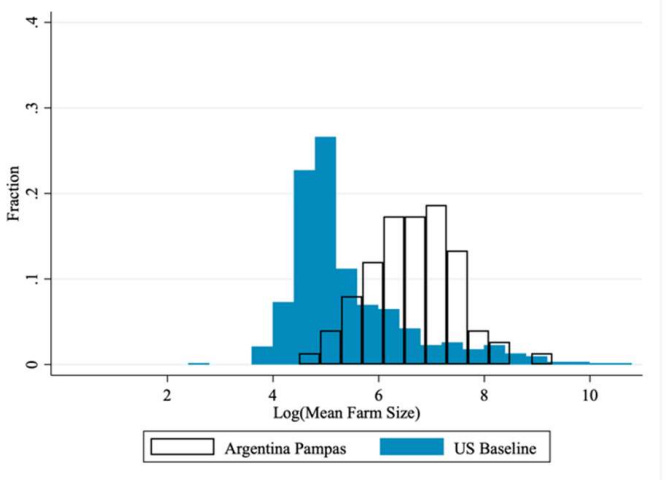

By the early 1914s, the average farm in Argentina was much bigger than in the US or Canada.

Just 2.5% of landowners held half of Argentina’s farmland! Why? The typical answer to this is:

“Institutions!”

Hold on, not so fast.

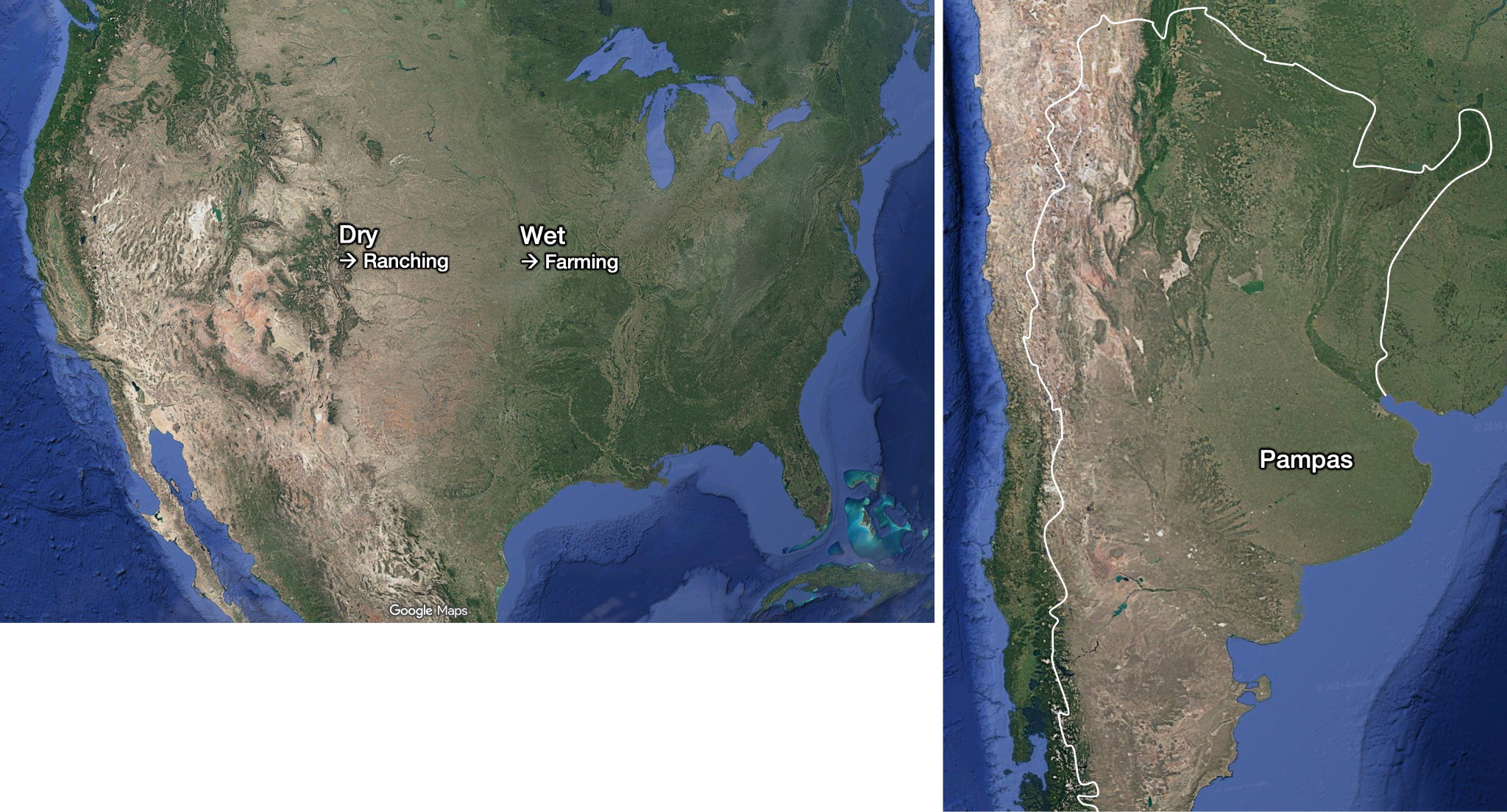

US East Coast farms were small, but those in states like Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas, or Missouri were much bigger—just 33% smaller than those in the Argentinian Pampas. Why? The climate in the Pampas is most similar to the climate in these Midwest states.

The rain in the Pampas region is more like that in the ranching part of the US Midwest:

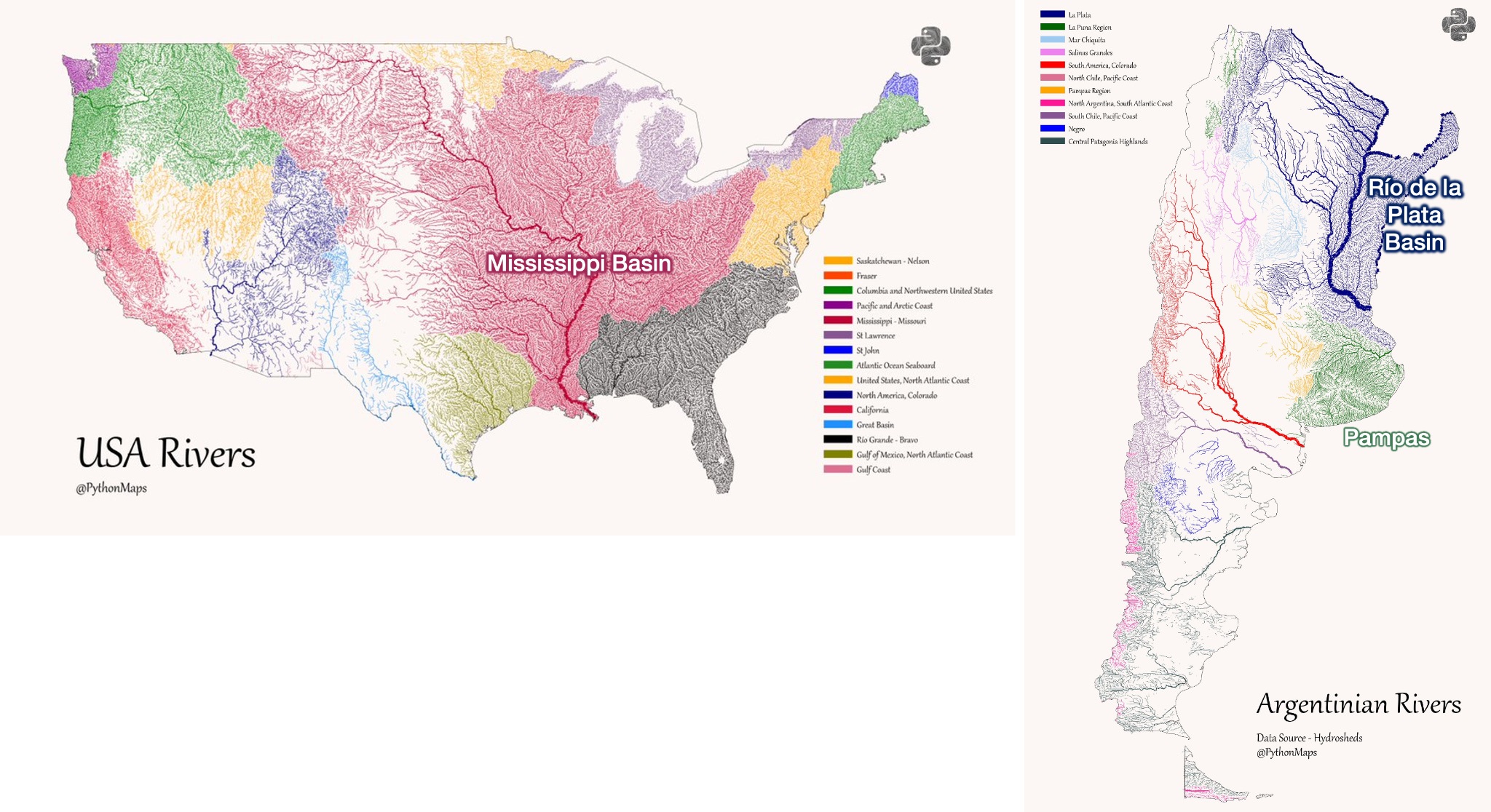

Also, whereas the Mississippi Basin irrigates the US Midwest, the Rio de la Plata Basin doesn’t irrigate the Pampas, which must rely mostly on rain for agriculture.

Less rain means less irrigation, and a harder time growing grains, but enough for grasses, which begets ranches.

Of course, this also meant that the Pampas didn’t have the navigable waterways of the Mississippi, which meant grain couldn’t be easily transported by boat to the sea. In fact, there was no easy way to transport grain to the coast because there weren’t even railroads in Argentina until the late 1800s. The only way to transport food production to Buenos Aires (the port to the world) was by making the food walk—that is, to have cattle. But as we mentioned before, cattle could hardly be exported because meat couldn’t be refrigerated until the late 1800s.

Additionally, as we just saw, the big wave of immigration into Argentina started late in the 1800s, so there weren’t many farmers to take care of farms anyway. Ranching requires fewer workers per acre, so it was a much more reasonable solution in a world of near-infinite land and limited people.

Ranches have economies of scale: The bigger the ranch, the more cattle heads, and the fewer cowboys / gauchos needed to take care of them.

So these are most of the reasons why Argentina had lots of ranching and little crop production until the 1800s. We’re just missing one.

The Great Land Grab

We saw that the majority of the farm size gap between the US and Argentina was due to geography, but not all, as Argentinian farms are still bigger than in the US region where they’re biggest. This paper suggests that the other cause of big farms was institutions: Spain and the UK had different ones, and they transposed them into Argentina and the US respectively.3