Can We See the Impact of Automation in the Economics Statistics?

Yes, but you need to look at the right place

This is the 3rd article in the Automation series. Article 1 covers what jobs will disappear, and article 2 how fast they will disappear.

Summary: There’s a bunch of reasons why we can’t see automation in the economics statistics, but the key one is that automation now mainly destroys jobs through the digital economy (soon, AI, and later, robotics) and the digital economy is very special, with high fixed costs that are going down, and near zero marginal costs. This is causing all sorts of effects in the economic data. But there’s one impact that can be seen in: inequality. This matters because if this is true, it will keep going up.

If automation will eliminate so many jobs, why can’t we already see it in the economics statistics?

This is the core argument that techno-foolish1 people use to claim that automation is unlikely to eliminate jobs. The following is a fictional conversation between a techno-foolish person and me, to illustrate their points and my take on them. I hope you enjoy it!

TOMAS PUEYO (TOMAS): I fear automation, especially AI, will destroy lots of jobs very fast and we won’t be able to create enough of them fast enough, which will drive us to lots of misery and social conflict.

TECHNO-FOOLISH (TF): “You’re such a luddite! This won’t happen. People have feared being replaced by robots for two centuries, since the dawn of the Industrial Revolution. And look at us today! An average person has access to more goods and services than the richest person 200 years ago. Unemployment is at an all-time low. Where is all this disruption we thought computers would bring? Why would this time be different?

Every time I read about this “rise of the robots” fear, I feel the urge to tear my hair out. While it makes a great science fiction story, so far there just aren’t any signs that it’s happening.”

TOMAS: I’m a techno-optimist like you. But I don’t want to be techno-foolish. Economists studying this usually look for signs of the impact of automation in four stats: unemployment, productivity, innovation, and inequality, right? So let’s look at each one. Let’s start with unemployment.

Unemployment

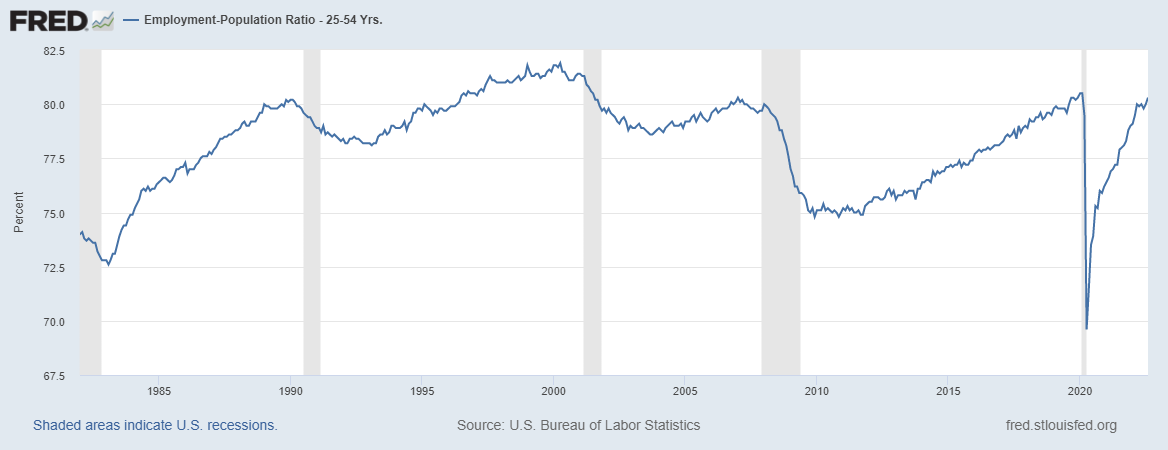

TF: In today’s America, almost everyone that wants a job has one. The prime-age employment-to-population ratio — in my assessment, the best single indicator of the labor market — is now at about the same level as at the peaks of 2019, 2007, and 1990.

TOMAS: What if we look at the data in a slightly different way? What if we go back to 1950 instead of 1980, and look at all people above 16 instead of those 24-552?

Interesting. This is not showing full employment anymore. What’s going on? Let’s break this down by men and women.

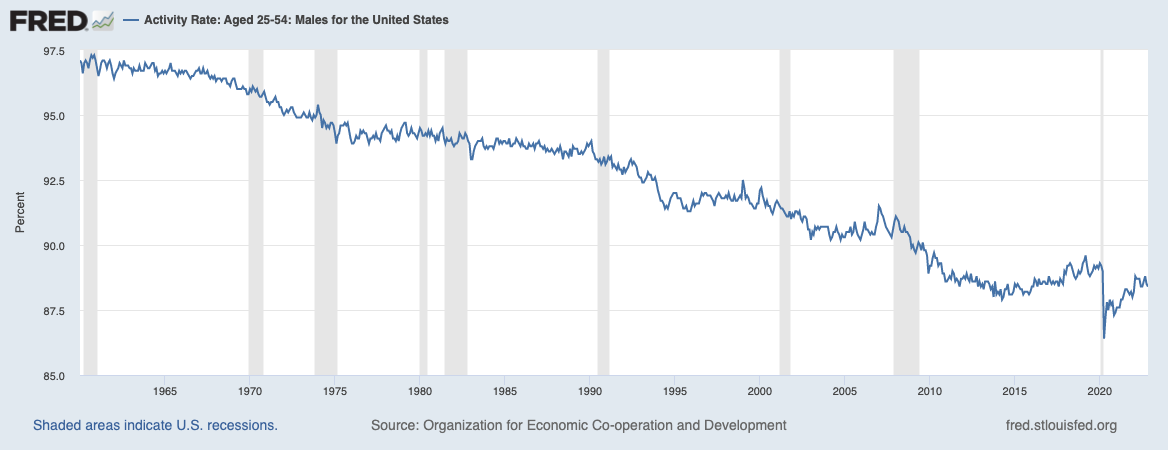

Of course, women joined the workforce in droves! This is great! But their participation rate has gone down since the 2000s… Now let’s look at men.

Ouch. 22% of men used to work but don’t anymore! This is not just a US pattern.

Here you can see the drop in participation of prime age male labor. It was at 93% in the US in 1990. The reason why it’s different from the level in the previous chart is because that one shows all males, not just prime age males. As we’ll see below, male prime age labor has gone down in the US too.

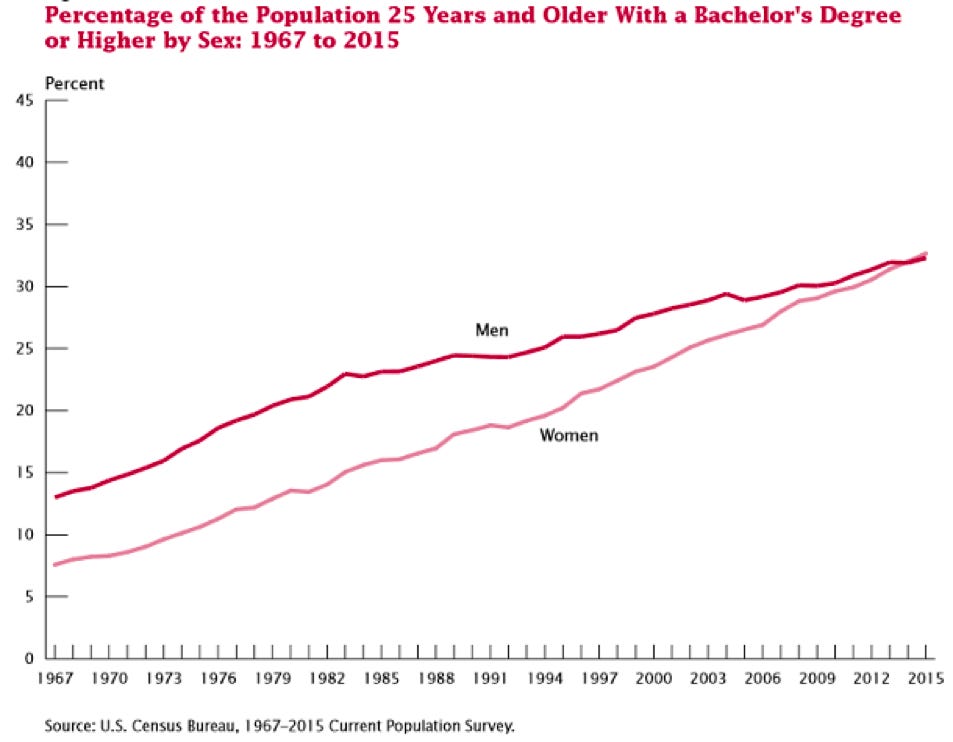

These are good trends! More females are working, people are studying more…

TOMAS: I agree. And there are many more. For example, the US population has grown 20x in the last 200 years. More population means more diverse needs, more specialization, more jobs.

Another force has been urbanization: When people move to cities, they become more productive, they consume more, and more niche jobs emerge.

Another force has been globalization: More countries participating in trade means higher global productivity and consumption overall.

Female work, education, population growth, immigration, globalization, urbanization, and many more3 have influenced work participation rates. It’s nearly impossible to look at these numbers in aggregate and tease out the impact of automation. For example, you could easily say: “Despite a unique spell of growth in which prime-age males have been improving their productivity by moving to cities and getting more education, they keep working less and less.”

Because that’s what’s happening:

If we can create completely different narratives on what’s happening based on the same data, it means this macro approach is not very useful. There are too many variables, and it’s impossible to isolate them all. To see the impact of automation, we need to dig into the details. So what exactly are we talking about when we say that automation will eliminate jobs?

TF: I agree! That’s why it’s important to dive into the details of innovation, and break down jobs into tasks.

Innovation: Jobs vs. Tasks

TF: Dozens of articles and papers have tried to weigh in on whether automation will kill jobs or not. Some claim it will eliminate 50% of jobs within decades, others that it will produce jobs. According to some economists who have studied hundreds of papers that discuss this, on balance, there will be job creation.

TOMAS: Maybe that's true. But every time I read one of these papers, I see the same flaw: They tend to look at jobs inside the companies that are doing the automating—or in adjacent companies. These are not the jobs that will disappear! The companies doing the automating will win. The losers are elsewhere.

TF: Where are jobs supposed to be disappearing then?

TOMAS: Let’s think about the industrial revolution. When machines came, artisans lost their jobs and low-skilled workers gained new opportunities working with machines and increasing their salaries. The winners were the ones doing the automating. The losers were those being replaced. What’s happening today?

When the number of travel agents halved in 12 years, it wasn’t because some travel agents invested in automation and became more productive than others. It’s because the Internet came, and companies like Booking.com or TripAdvisor eviscerated them. But we only need a few companies like Booking because they build things once and can then serve every customer on Earth. That means Booking and its competitors employ a fraction of workers compared to old travel agencies.

Google and Facebook are the big ad behemoths. Within a decade, they eclipsed printed advertising revenue, and with it the livelihoods of tens of thousands of journalists. And since Google makes 10 times more per worker than newspapers, they employ 10x fewer employees for the same level of revenue. Not a great way to create jobs…

Netflix obliterated Blockbuster, creating 130x more value per employee, and destroying tens of thousands of jobs4.

Kodak had 150,000 employees in the late 1990s. Then Apple’s iPhone came along. The nail in the coffin was Instagram, created by a team of a dozen people, and sold for $1B, for nearly $100M of value created per head. Now most of your photography needs are much better covered than with Kodak, but you also spend much less on photography. Most of Kodak’s employees were laid off, but photography has not created equivalent companies.

The same pattern happens over and over: Digital economy companies5 are much more efficient, so they destroy traditional industries. But this efficiency increases the quality of products while cutting the price. They have fewer employees, and the ones they have make more money.

WhatsApp, sold for $22B in 2014, created $400M of value per employee.

The result is that the Tech share of GDP increases.

And Tech’s productivity is through the roof, compared to other sectors (as we saw before).

These companies’ employees are so productive that they are among the best-paid. 12 of the top 25 companies in terms of median salary in the US are in Tech. Companies like Alphabet (Google), Meta (Facebook), Netflix, or Nvidia pay over $200k per employee per year as a median6!

So why are all the papers missing the impact of automation today? Because the creation of most of the good jobs is happening in the online digital economy, and the destruction is happening across other industries.

From Variable to Fixed

TOMAS: And you know what makes the digital economy special: Zero marginal costs.

Outside of Tech, most industries have a big marginal cost: Every time they serve a customer, they must pay for the manufacturing of the product, the packaging, the transportation, the retail rent, the salesperson… Each one of these activities requires people7, who cost money. This means wages for all of them.

Online digital products don’t work like this, because bits can copy digital products infinitely for close to nothing8. Tech companies spend most of their budget in building their product, which is a fixed cost. That means the founders and the few people needed to build and distribute the product (those responsible for that fixed cost) share all the value created9.

If you have variable costs, it’s very hard to compete with a company that doesn’t have them. So a very typical mechanism of automation destroying jobs is by companies turning a variable cost into a fixed cost, then reducing prices, then expanding the business, eating the lunch of incumbents, and killing entire industries.

If we look for this effect in the data, we find it:

The graph shows the evolution of average productivity, broken down by whether industries are becoming more productive, people are moving to more productive industries, or they’re moving into industries that are becoming more productive.

It turns out that the entire increase in productivity comes from industries becoming more productive. That makes sense: Tech is making people more productive. Every hour of work is producing more.

But if this increase in productivity was so good that productive Tech companies needed more workers, we would see workers move into more productive industries. This is not what we see.

What we see is workers moving to industries that are less productive. Not only that: They’re moving to industries that are shrinking in productivity (think education, construction, or healthcare).

This is consistent with the story that is unfolding here: Tech becomes more productive and employs more people as a result. But it also destroys other industries. Their employees must move into other, lower productivity industries10.

This is why many job and task analyses miss the impact of automation: The companies doing the automating employ more people. The ones suffering are in other industries. And on balance, companies engaging in automation employ fewer people than the jobs they destroy in other industries.

TF: What about other innovation statistics, like patents?

Patents

TOMAS: What company has the most patents?

And yet IBM is not a digital economy company11. Similarly, other companies with lots of patents tend to be involved in hardware more than software, which also means they have marginal costs.

The few software companies that publish patents are doing some serious fundamental research, like Google on AI. For the rest, they’ve realized that it’s hard to protect their advantage through patents, and it makes more sense to have other defensibility mechanisms (like network effects or brand, for example).

As a result, online digital economy companies publish fewer patents than their innovation and revenue would suggest.

So if you’re using patents as an indicator of innovation, you’re going to believe innovation is decreasing, even if it’s increasing.

Robotics

TF: What about robots? Robots are correlated with — and probably cause — higher employment in the companies and areas where they’re adopted. What’s happening is that companies that use more robots hire more humans (and retain their existing humans) in jobs that complement the robots. That’s exactly what we saw with previous waves of automation — people find new roles, robots increase their productivity, and they get paid more. Looking at the countries that use the most robots in their manufacturing industry, it seems likely that this virtuous cycle is happening even at the level of whole nations.

TOMAS: That is probably true. Researchers love looking at robots to measure the impact of automation: It’s much easier to quantify the investment in machines, and see how each machine impacts jobs, than to notice in the statistics what a human can create armed with a computer, an Internet connection, and a couple of software applications. The result is that most research that looks into the impact of automation of jobs is centered around physical machines and robots. But robotics have two barriers that the digital economy doesn’t have:

They produce physical products, so they have marginal costs, so they have to employ lots of people.

Robotization technology is not good enough to fully replace humans. For example, many tasks in the textile industry have proven impossible to automate. AI might change this, but we’re still in the phase of fundamental research here.

The result is that robotic automation behaves differently than computer/Internet/AI automation. For now12.

TF: It would take a breakthrough in robotics to fully automate the production process. This would definitely destroy jobs, but you’d still need the products to be packaged, transported, and sold, so robotics automation won’t annihilate broad swaths of jobs any time soon.

TOMAS: I agree. As I mentioned before, my guess is that the breakthrough will come from the application of AI to robotics, which will open up the physical, non-routine tasks to automation. I believe this will happen in the coming years, but until that happens, these jobs are safe. They’re not the ones I worry about the most imminently.

TF: OK so we agree on that one. What’s next?

TOMAS: Productivity data.

Productivity vs The Great Stagnation

The computer age is everywhere except for the productivity statistics.—Solow Paradox.

TF: Yes, our growth has been terrible in the last few decades:

Our total factor productivity (TFP)13 was growing very fast in the past, but appears to have slowed down since 1973. Shouldn’t we see it pick up thanks to automation?

TOMAS: The great stagnation theory always takes 1947 as the baseline, which sounds awfully biased since it’s just after WWII, one of the best economic times in all of history thanks to the post-war reconstruction, especially for the US given its sudden role as the biggest world power, lending money to its allies so they could buy US products.

Also, other factors can have caused this slump: the end of Bretton Woods in 1971, the oil shock of 1973, globalization, the baby boom…

The Internet economy couldn’t have caused this slump, since it started growing in the 1990s, increasing productivity then (productivity increased in the 1990s and 2000s). So that’s one possibility.

TF: Then shouldn’t we see productivity continue increasing in the 2010s?

TOMAS: Perhaps. But maybe we don’t measure productivity well.

Tech Is Deflationary

TOMAS: Sometimes, it’s healthy to raise our nose from our spreadsheets and look around.

When Blockbuster expanded internationally, it had to build subsidiaries in every country, employ locals, negotiate with national and local governments, buy videotapes, ship them, maintain them, replace them… All of these cost money on top of what they already spent, which meant higher prices.

Netflix has none of that. They built their internationalization infrastructure, and after that their international strategy is mostly translations. So Netflix actually reduced prices as it expanded internationally14.

When most of your costs are fixed, and variable costs are nearly zero, you want as many customers as possible to spread the fixed costs. You are motivated to keep your prices low or even reduce them to gain market share. The result is a world that can see Netflix for $10 per month or less, or use Google, Facebook, YouTube, TikTok, and Wikipedia for free15.

Despite these variable costs close to zero, Tech companies haven’t taken over the world yet. What has prevented them from doing so?

One element has been internal tools for things like payments, security, development, quality assurance, project management… Early on, Tech companies had to develop these things internally. But over time, SaaS companies16 have been automating them, making these tasks simpler and cheaper. The result is that it costs less and less to create a digital product.

Another barrier to the adoption of Tech products has been infrastructure like processing power, data storage, or bandwidth—the sort of deflationary products that have exponentially increased their performance while reducing their price year after year for decades. You end up with a reality-altering product like the iPhone, with its universe of apps, but barely notice either on the economic statistics, simply because they’re both deflationary.

So for the digital economy, variable costs are near zero, fixed costs go down over time, and the infrastructure they depend on becomes cheaper and better over time. The result is a deflationary industry that gobbles up the rest of the economy.

Naturally, intelligent people notice this. They realize this is the way to get fabulously rich or have a big impact. So entrepreneurs, inventors, and investors flock to it, leaving other industries, which don’t become more productive. This further accelerates the deflation from Tech at the expense of more inflationary industries.

Digital media consumes a large and growing share of our waking lives, but these goods and services go largely uncounted in GDP. That’s because the measure is based on what people pay for goods and services. If something has a price of zero, then it typically contributes zero to GDP.—Erik Brynjolfsson and Avinash Collis, How Should We Measure the Digital Economy?

TOMAS: Also, this whole process takes time.

It’s Still Early

There will be a period when the technologies are developed enough that investors, commentators, researchers, and policy makers can imagine their potentially transformative effects.—Artificial Intelligence and the Modern Productivity Paradox, Brynjolfsson et al.

TOMAS: It took 50 years for electricity to truly impact productivity. For decades, factories were organized around the steam-powered shaft. The benefits of changing steam power to electricity were low, but the cost was high.

The true value of moving to electricity only became obvious once the entire manufacturing concept was rethought from the ground up, which happened decades after the discovery of electricity and electric motors17.

We’re still in the early phases of Internet deployment. The Internet and computer technologies still account for a small share of the economy, and we haven’t fundamentally rethought how we work around them. For example, it took a pandemic to get us to work remotely. But the bulldozer of software continues eating the world.

Tech companies started with the low-hanging fruit, with the explosion of the 1990s and 2000s. Then we had cloud computing and mobile. Now we have mobile, remote work, AI, no-code, crypto, VR, soon AR. This is a trend that takes decades, not years. As these tools become more widespread and a bigger share of the economy is eaten by software, its impact on economic statistics will become more obvious.

It wasn’t until the late 1980s, more than 25 years after the invention of the integrated circuit, that the computer capital stock reached its long-run plateau at about 5 percent (at historical cost) of total nonresidential equipment capital.—Artificial Intelligence and the Modern Productivity Paradox, Brynjolfsson et al.

If we summarize what we’ve discussed so far, this is why it’s hard to see the impact of automation on economic data:

We can’t see it in aggregate data of unemployment: There are too many confounding effects.

Most of the impact in the last few decades—and in the future—is likely to come from the digital economy, which has some peculiarities.

Patents are mostly irrelevant in the digital economy.

Most research on automation pays attention to robotics and physical machines rather than the digital economy.

Tech is deflationary, so it makes sense that you wouldn’t be able to see it in productivity data.

In fact, when we break down productivity data into its components, we see that the story is consistent with the ravages of the digital economy, as productivity improves in individual industries, but is reduced by people being displaced into lower-productivity industries.

TF: You’re agreeing with me then! We can’t see the impact of automation on unemployment, innovation, or productivity data. Does it matter? Should we even worry?

TOMAS: Yes, because where we can see it is in inequality.

Inequality

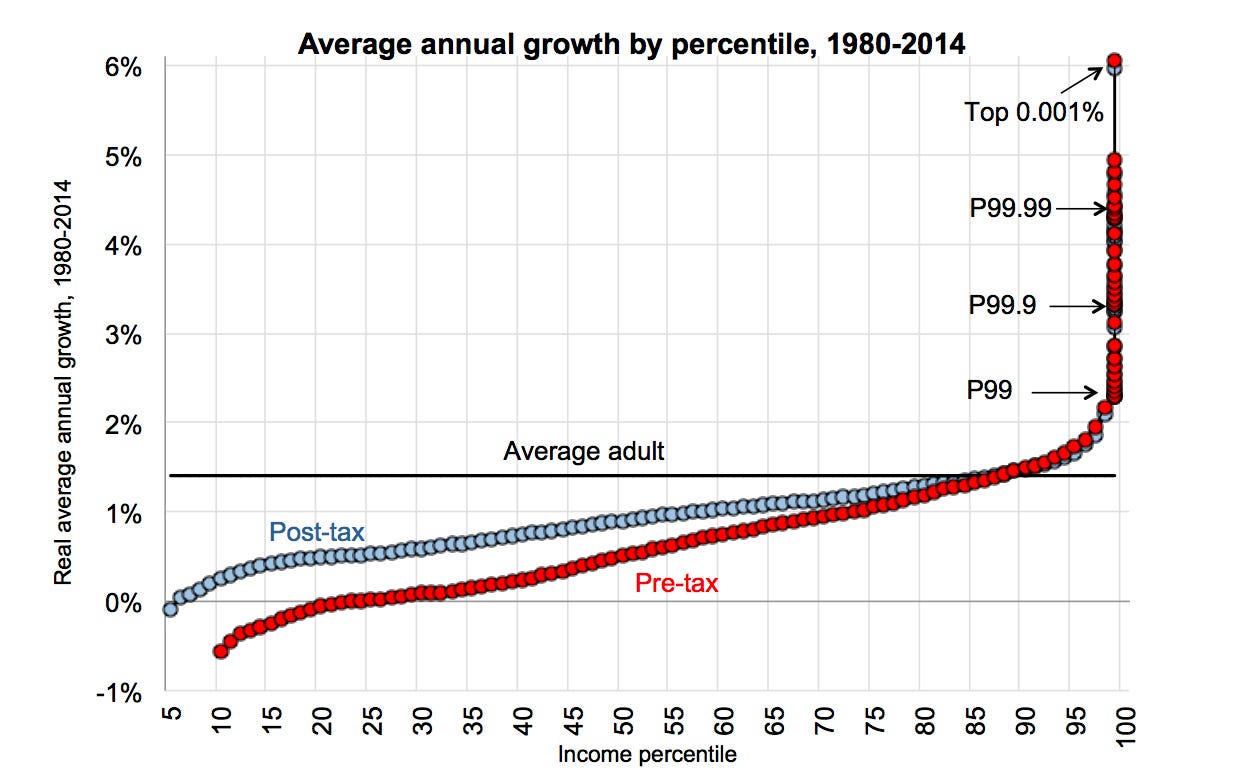

TOMAS: The story I’ve been painting suggests that the digital economy creates a few rich people while it destroys other industries and their jobs. Some people are able to recycle into better jobs, but the vast majority have to move to lower-paying ones.

If this is true, we should see inequality rising, with more high-paying jobs, more low-paying ones, and a hollowing out in the middle.

Conversely, if the digital economy is not destroying jobs, we should see inequality stable or shrinking, and plenty of new industries appearing to employ many more people. Is that what we see?

Do We Have New Jobs?

TF: We do see many more new industries employing more people. Just consider all the new jobs that didn’t exist a few years or decades ago: social-media manager, data scientist or podcast producer.

TOMAS: How many social media managers are there in the world? How many podcast producers? And why do you use these examples instead of the jobs that have actually grown with Tech, such as the over 3.5 million Uber drivers or Amazon’s more than 1.5 million workers—most of whom work in logistics?

The truth is that automation has created a lot of low-paying jobs and a few high-paying ones, while automating many more.

Here are the top 50 most common jobs in the US. 47 of them have been around for 60 years or more:

The only three new ones are, you guessed it, linked to the digital economy: software developers, support agents, and computer information analysts. In other words, two of the only three new jobs that employ a lot of people are trying to automate everybody else’s job.

Automation in the US has led to a polarization of the labor market: Middle-income jobs that used to perform routine tasks were replaced by lower-income jobs, while those at the top of the income distribution experienced significant gains, leading to an increase in economic inequality.—Why are there still so many jobs? The history and future of workplace automation. Journal of economic perspectives. David Autor.

TOMAS: And this is not just in the US. The same is happening in the OECD.

If this was true, we would see an increase in income inequality. We do.

Across OECD countries, the share of income going to the top 1% has been growing. So why can’t Skeptics see it? There are at least three reasons.

Cutting Data

TF: But for the last decade or so, wages at the low end of the distribution (1st and 2nd quartiles) have been outpacing wages at the high end.

TOMAS: I looked at the source of the data, and I think you get a clearer picture if you actually compare high-skill vs low-skill jobs:

This tells the opposite story! But I’d argue high skill vs low skill pay is closer to what we’re talking about than quartiles.

The most famous researchers on this topic, Acemoglu and Restrepo, just published a paper showing something similar. Here’s the graph, indexing salaries to 1963. We can see the big divergence since the 1980s.

Notice one more thing: These are wages. That’s the lion’s share of people’s income… But not for the richest.

Capital Gains

TOMAS: The richer you are, the more you make from your investments and businesses rather than your wages.

Calculating income just from wages will miss out on the biggest source of inequality.

Also, this is consistent with the story I shared previously: If the digital economy is one of the biggest drivers of inequality, then founders and early employees are the ones making most of the money. And how do they make most of it? Not through their salaries. Through stock and stock options. They earn shares of the companies that grow to be worth billions.

Not only that, but usually the taxation on this income is advantageous.

Taxation

TOMAS: The taxation for long-term capital gains tends to be much lower than for wages. In the US, the top income bracket at the federal level pays 37% of taxes from compensation, but only 15% for capital gains.

That said, taxes do reduce inequality.

Look at the red line. It shows that, between 1980 and 2014, the richer you were, the faster your income grew. Those in the bottom 20% actually make less money now than they did in 1980 (the red line dips below 0% at the 20th percentile). The income change really grows exponentially for the top 0.1%, and even faster for the top 0.01%, and so on. So the red line is a stark illustration of growing inequality. The blue line, meanwhile, shows that the income inequality after redistribution (taxes and social services) is much lower than before taxes: The blue line is above 0% annual growth for all workers, and is above the red line for all but the richest.

And this is true across the OECD.

For each country, the red line shows the Gini coefficient of inequality for that country before redistribution, and the blue line shows it after. We can see that the US is among the most unequal countries, but it also has a lot of redistribution.

TF: What does it matter? If inequality is tamed by tax redistribution, isn’t the system working?

TOMAS: This matters because if inequality before taxes is increasing, it means the economic system, fueled by automation, is causing this inequality. More of the same will mean more inequality before taxes, which gives those owning that wealth a bigger reason to use their wealth to reduce taxes—or to escape taxation altogether.

Summary: Why Some People Don’t See the Impact of Automation in Economic Statistics

The big story of automation in the last few decades and the coming ones should be the impact of the digital economy—with its computers and Internet and AI and mobile and VR—not robot automation or simple computerization.

The digital economy has something special to it: Because it has mostly fixed costs and not variable costs, it concentrates wealth in the few builders, not on many operators.

If that’s what’s happening, we should see the productivity of individual industries increase, while people who are pushed out of their jobs move to lower-paying jobs in industries safe from the digital economy. That’s what we’ve been seeing so far.

Another way we should be able to see this in the data is through increasing inequality. We do.

This is accelerating, because the development of the digital economy is exponential: The more it grows, the better tools appear to build digital products, the more digital infrastructure is developed, the more people are educated about digital products, and the faster penetration of new digital products becomes, destroying other jobs faster.

When Skeptics don’t see the inequality in the statistics, it’s usually because they don’t account for capital gains or redistribution.

We shouldn’t see the impact of automation in other places. For example, aggregate unemployment data: There are plenty of confounders.

Also, people need to eat, so they still need work, even if they work in worse jobs overall. So unemployment won’t be the canary in this coal mine, it will be inequality.

We can see this in productivity data, with people moving to lower-productivity jobs. That’s their only option.

And males are dropping out of the workforce too.

We can’t see the impact of automation in the economy through patent data, because patents don’t matter as much in the digital economy.

We can’t see automation destroying jobs in firms and industries that invest in automation, because these are the winners: They increase their productivity and employ more people. You need to look at the industries they replace. Those are the ones suffering.

We can’t see it in robotization because at this point, robotization would need a big jump in productivity from AI to start automating core human tasks. The action is more on the digital economy side.

We can’t see it in productivity data for several reasons: The reference of WWII is biased, the slump predates the Internet economy, there are confounding factors, it’s still early, and Internet technologies are deflationary. Oh, and it might have still increased productivity despite all of that (seen as the bump in the 1990s-2000s).

In other words: All the numbers we’re seeing are perfectly consistent with a growing automation that is destroying jobs, led by Internet technologies.

Let’s be clear: I’m not categorically stating that most jobs are doomed and we’re about to fracture society. What I’m saying is that we can’t tell yet, but there’s a serious chance this might happen.

Why does it matter?

“When labor becomes electricity, the cost of physical goods plummets18. The robotic economy holds the promise of making everything far cheaper, of ushering in an age of abundance. We just need to get to the other side of this coming economic disruption in one societal piece.”—Balaji Srinivasan.

We can’t stop technology. And neither should we try: In the long term, it makes everybody’s lives much better. But technology can create major social trauma in the short term. We can’t ignore that.

Fearing technology is naive.

But denying its job-destruction potential is dangerous.

We need a plan to solve this.

I will write about this topic in future articles, including things like:

How might inequality evolve?

How might this lead to societal collapse, and how can we avoid it?

Why should the history of the industrial revolution scare us for the next few decades rather than comfort us?

Subscribe to receive my newsletter.

Like techno-optimists, but too optimist!

I agree that the employment population ratio is a good measure of employment, and that looking at the US is enough to get a sense of the impact of automation in the world. The US is probably the canary in the coal mine anyways.

More examples include: The Green Revolution, the end of Bretton Woods, the oil shocks of the 1970s, the curtailment of nuclear energy, the Baby Boom, the subsequent NIMBYism, the emergence of cars and the car economy, the reduction in unionization…

In the process, it attracted more competition: Amazon’s Prime Video, Disney+, Apple TV… But it would take 130 Netflixes to create the same employment for the same productivity. Now it’s interesting because Blockbuster didn’t create content, whereas Netflix does. And so Netflix is not just replacing Blockbuster, but also part of the studios. All of that with fewer employees than Blockbuster alone.

I will call them digital economy companies or Tech companies as a shorthand. The most successful ones also tend to be funded through venture capital. Obvious examples are Google, Facebook, Pinterest, Snapchat, etc. Other examples also include Amazon. Although it has a lot of physical operations, the core of its value is its marketplace, and now its adjacent businesses of servers and ads. I also include companies like Uber or Airbnb, which do manage physical cars and listings, but don’t own either. Their value is mostly on the digital platform.

Tech wins whether you look at S&P500 data reported to the SEC or through Glassdoor data, reported by employees.

For now. But it looks like one of the last frontiers of automation will be robotics, unless AI can create a breakthrough here. There are also other costs, like the land for retail.

There are some marginal costs in tech. There are server, security, and payment costs for example, but these tend to be a very small share of revenue. The biggest marginal cost is usually marketing and sales, because Tech companies compete for the scarce resource of attention, so they bid up for it, to the delight of Google, Facebook, and Apple, who end up gobbling up a huge share of the value created by Tech.

This is different if there’s a marginal cost. If it’s mostly advertising, most of the spend goes to Google or Facebook, while the marketing teams share on the value creation. If there are sales teams, this typically includes a lot of people, although I assume the average revenue per salesperson in Tech is much higher than in other industries. Marketplaces are yet another type of business, where many people do make money (even if the marketplace rakes in the most value). We’ll talk about these later.

This is a long-term trend, so it doesn’t just include computers, the Internet, or AI. It also includes physical machines. We need to be careful to differentiate the different behaviors between these industries.

And hardly considered a cutting-edge innovator.

It makes sense that the forces that apply to digital products don’t yet apply to robots.

Total Factor Productivity is the improvement in productivity that can’t be attributed to more labor or capital. In other words, it’s the “other stuff that makes us more productive”. Normally it’s interpreted as knowledge in general.

They also create local content, and it turns out that people love that. But this is interesting: The local content sometimes works very well in other geographies. Also, this is above and beyond what they used to do, now encroaching not just on Blockbuster, but on local film production.

Of course, most of these monetize through ads. But ads don’t make much money per impression. The only way these services can afford to give these services away for free despite making little ad money in return is because the marginal cost of servicing that ad is near zero.

Software as a Service, companies that build these tools once, and then can sell them infinitely at near zero marginal cost.

Electric motors were invented in 1834. In 1890, there were already over 1000 electric power plants in the US. Steam power engines only peaked in 1910.

He uses “hyperdeflates”, but I’ll take a replacement license for comprehension.

Perhaps in the rise of the USA populists and violence we are already seeing the beginning of the implosion of society due to the rising inequality and the song of angry men.

I'm 68 and a geek grad from 3 letter school. On the DARPANET in 72. Seen all the tech evolution from mainframes to DEC to PCs to laptops to phones. Saw how PC based solid modeling like Solid Works replaced drafters in automotive as engineers did more and most of the whole design and analysis of parts and subsystems.

I love Noah Smith.

My observation as an active participant over 50s years in this topic follows.

A. Yes, automation eliminates jobs. Drafters, admin/secretaries, travel agents.

B. Totally agree that the variable cost of IT amd automation is incredibly low

C. Physical products still require component manufacturing, tooling, assembly and test.

D. Unfortunately the Apple et al determined that China wae an easier route than US labor (it's competitive here in Arizona, plus automation) would probably raise an iPhone variable cost by one dollar. Or 2. Meaningless actually

E. The long arc of allnof this is interesting to me:

Conclusion: Not enough work is very very bad. Coupled with today's lower work ethic in under 35 yr olds, it's gonna be a huge problem.

Meanwhile labor has 2 core issues.

1. Struggle forna living wage

2. Struggle for Healthcare payments

Solutions:

A. National Healthcare. Saves $2.5 Trillion annually of non value. Move from 20% GDP back to 10% GDP.

B. This allows worker mobility to optimize jobs and equally allows startups to hire a BigCorp talent afraid to not have Healthcare.

C. Mandatory lower working hours. Overtime is illegal. Minimum wage $20/hr.

Productivity to infinity is 1 person making 500 million cell phones in a Foxconn factory. With millions unable to be supported.

Sustainability requires deliberate UN-Productivity.