Cathedrals of the 21st Century

What Will They Be?

If you visit any European city, odds are you will go see the cathedral.

They were designed as social gathering spaces.

These are majestic buildings, so expensive that their cost frequently absorbed all productivity improvements in the surrounding economy.

A lot of that money was spent intricately decorating their exteriors.

And interiors.

They were built to inspire awe.

These decorations told stories about Christianity: Jesus, the apostles, the history of the Church, important local events…

At a time when stories were mostly spoken, cathedrals were one of the only other ways that people could follow them.

So cathedrals had a public gathering component, but also educational and display components.

Unbeknownst to many today, cathedrals were not just meeting places for religious purposes:

When a service was not in progress, [people] would meet their friends here, bring in their dogs and their hawks, arrange trysts, eat snacks, etc. The poor might even bed down for the night in the gloomy recesses. Stalls clung like limpets to the walls of the building. At Strasbourg, the mayor held office in his pew in the cathedral, meeting burghers there to conduct business. Wine merchants, perhaps employed by the chapter itself, even sold their wares from the nave of Chartres – selling inside the church, they were exempt from the taxes imposed by the count of Blois and Chartres.—Source.

And these cathedrals had a single sponsor: the Church.

Each diocese wanted a bigger and better cathedral, to show how much better they were than their neighbors. But you can only do that when you have so much power you can control local economic output.

That’s why most famous cathedrals were built between 1000 and 16501—the height of the power of the Church, which was pushing to enshrine its values.

So cathedrals were beautiful buildings that changed the skyline of a city because some sponsor spent a lot of money to signal the values of the time and so that the public could gather and connect.

Put this way, we can see that each period has its own “cathedrals”.

Cathedrals of Times Past

Ancient civilizations had pyramids, which were also usually beautiful buildings that changed the skyline of a city because some sponsor spent a lot of money to build them for social gatherings and to signal the values of the time.

There are a few differences, of course:

Pyramid makers did not know how to build big, empty, vertical spaces that didn’t crumble so they just piled matter up.

They might not have always been built for social gatherings and rites.

Like cathedrals, the values they fostered were also spiritual, but they had a strong secular component: to celebrate and enshrine the power of the ruler.

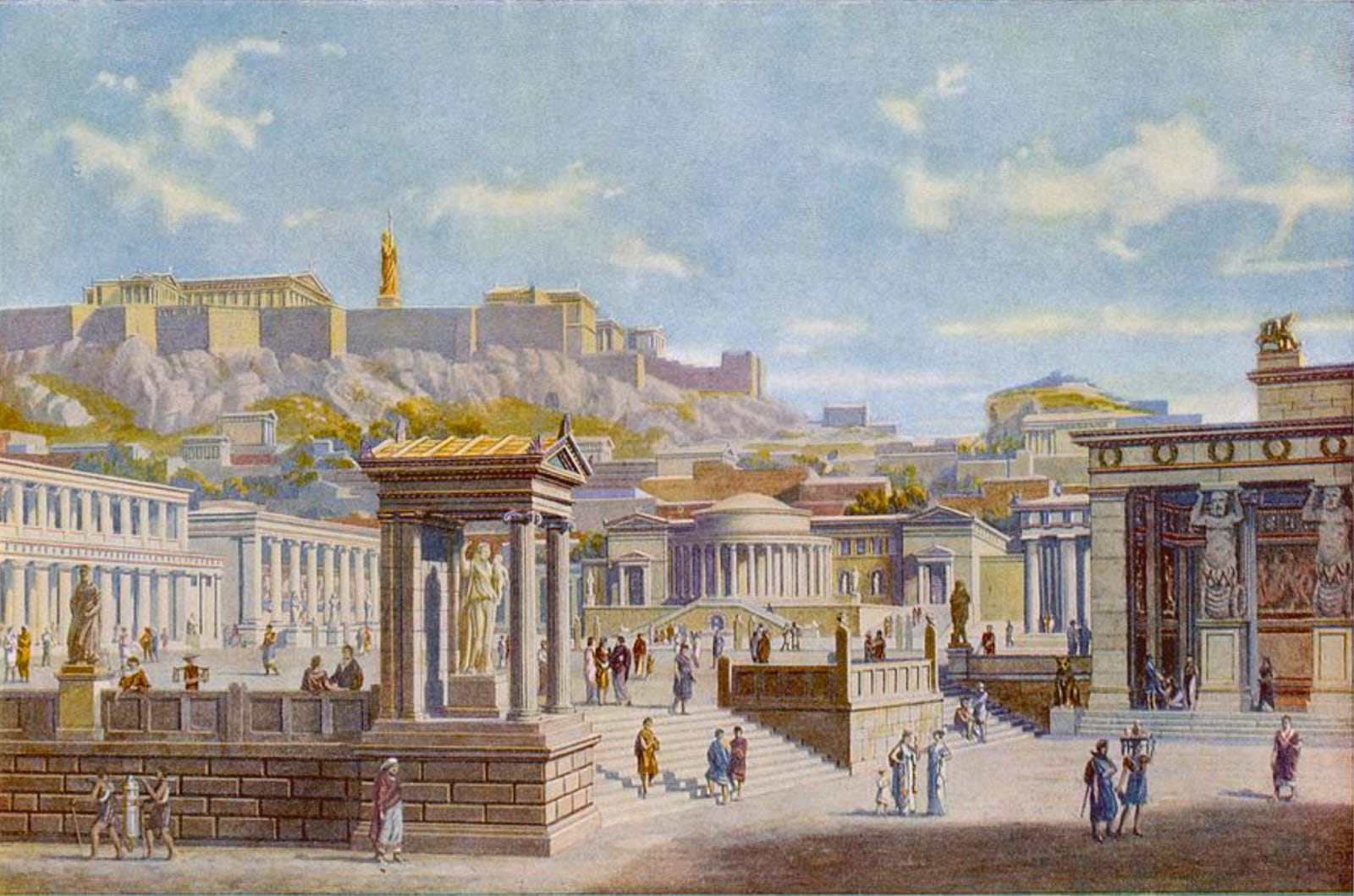

Later on, Greeks and then Romans had temples.

This is also true in other parts of the world.

Ancient civilizations had other types of “cathedrals” too. They had theaters.

Like cathedrals, these are beautiful buildings that changed the skyline of a city because some sponsor spent a lot of money to signal the values of the time and so that the public could gather and connect. In this case, however, the main value to promote was less spiritual and religious, and more emotional and artistic. The builders wanted to push the intellectual boundaries of their time.

Forums also achieved that goal, albeit with a philosophical and political slant.

In Athens, the agora and pnyx (“ekklesia” in Greek, does that sound familiar?2) were places for the public to gather, discuss, and make political decisions.

But they also had more ludic “cathedrals”, like amphitheaters and baths.

These were meeting places, to enjoy some rest and entertainment, to display wealth, to see and be seen, to talk with friends and neighbors.

Sometimes, they were inconceivably massive:

Medieval Cathedrals

The idea of forums and academies would evolve into universities, cathedrals of knowledge also originally sponsored by the Church.

Of course besides the Church, one of the biggest centers of power has always been the State, and the heads of state have always wanted to project their power. They also sponsored beautiful, expensive buildings that changed the skyline of the city for social gatherings and to signal the values of the time. In medieval times, the secular power was represented by castles.

Unlike cathedrals, mainly focused on software3, castles had a very important hardware function: defense.

Most of their budget was dedicated to adding defensive features, so the budget left for decoration was smaller. Still, the wealthiest nobles wanted their castles to represent their power.

And of course, castles were defined as social gathering spaces, where administrative and market functions happened in peacetime, and soldiers and civilians gathered for protection in wartime. Since warring was a constant threat in feudal times, these buildings represented the values of the time.

But as religious and feudal times faded into the modern period, castles and cathedrals were replaced by palaces.

Modern Cathedrals

Palaces concentrated a lot of the power that had been split between castles and cathedrals.

Sometimes, they retained some defensive function. But frequently they lost it, with specialized fortresses and defensive walls built elsewhere.

These beautiful palaces projected the power of their patrons, represented the values of their time (the power of absolute monarchy and high nobility), and served as social gathering spaces for court and aristocrats, but also for administrative purposes.

But this was also the time of global discoveries and trade. As the new values of trade and capitalism emerged, so did their cathedrals: the trading houses.

Venice, Lisbon, Sevilla, London, Antwerp, Amsterdam, Hamburg…

The wealth this trade generated was reflected in the guild and trade houses of their sponsors.

And of course, in the buildings for port trade.

Everything changed in the 1800s.

Industrial Revolution Cathedrals

While Napoleon smashed European monarchies, on the ground and in minds, the ideas of nations, republics, and equality spread across the continent, and new cathedrals reflected these new values.

Sometimes, the buildings reflected the changing values: new uses for existing buildings that represented past values.

But many times, previous political cathedrals were not available or suitable, so new ones were built from scratch, usually better suited to their purpose and more magnificent than their predecessors.

This is the time of the Industrial Revolution, brought about by the steam engine and its main use, the locomotive. Train stations became new cathedrals of the value of productivity and efficiency. People gathered in them to board trains, but also to admire the stations.

Of course, the steam engine also facilitated manufacturing, another cathedral of its time, although one where functional optimization prevailed over beauty and awe, so fewer astonishing manufacturing plants survive to this day.

Theaters, opera houses, and museum buildings picked up the baton of the arts.

As the 20th century began, these values evolved again.

20th Century Cathedrals

In many aspects, the 20th century continued the trend of the 19th century: more parliaments, more theaters, more opera houses, more museums. But new cathedrals emerged to reflect the values of the time.

In transport, airports took over from train stations.

Big manufacturing plants representing gathering places for industry were replaced by skyscrapers—gathering places for services.

The display of capitalistic values from wealthy sponsors won’t be lost on people, with names like the Sears Tower or the Chrysler building.

Sports arenas emerged, echoes of ancient circuses that channel young males’ violent impulses that are dampened by prevailing peace.

We can also probably count casinos and malls into 20th century cathedrals.

So the uniquely 20th century cathedrals have been airports, skyscrapers, sports arenas, malls, and casinos. They represent the importance of transport, capitalism, and entertainment. The best ones were beautiful buildings that changed the skyline of a city because some sponsor spent a lot of money to signal the values of the time and so that the public can gather and connect.

Then what will the cathedrals of the 21st century be?

To answer that question, we first need to understand why cathedrals have such an effect on us. What’s their psychological purpose?

The Psychology of Cathedrals

One psychological aspect of cathedrals is direct and obvious: The bigger and more beautiful, the more they give status to their sponsor. Building a cathedral is like burning cash: It shows you have a lot of money.

But pushing the standards of beauty also shows you have refined taste.

Gothic? More space and light to convey the awe of God.

Baroque? Fill your Church with ornaments to counter the austerity of the Protestant Reformation.

Chinese porcelain? You value trade and the exoticism of China.

Arabesques? You are not an iconoclastic infidel.

These are all signaling goals. But signaling is just using symbols. Is there more than that, though? Something that taps into fundamental human nature?

The Innermost Cave

In The Hero with a Thousand Faces, Joseph Campbell explains that in most mythological stories, the most important moment of a story is when the main characters get their key insight, and that usually happens in a cave. Why?

His interpretation is that caves are surreal. Your senses betray you. Light disappears; the echo distorts voices; water trickles down the walls; cold and humidity invade your skin; dangers can lurk anywhere. This feeling of otherworldliness heightens attention and makes events memorable.

Cathedrals achieve the same goal. Their colossality, their mesmerizing decorations, the echo from their tall stone walls, the cold that hits you when you enter, the general shadow pierced by colored lights… All of them are designed to induce you into this heightened sense of presence, like a trance.

It’s clear that’s what they’re trying to achieve because of the events that take place inside. Prayer is guided meditation, where you repeat litanies over and over to enter a state of trance. The voice of the priest and the monotonous words are not a bug, they’re a feature. The highly structured ceremony, the colors of the clothing, the symbols, the silence, the murmurs… All are there to foster this otherworldly sense.

You can see similar processes at play today in places like courtrooms or parliaments, albeit more subdued: They are big, solemn, sound is controlled and there are ceremonies, serious uniforms…

But you can also apply the same principles and end up with a completely different setting and experience: nightclubs.

The Saturation of Senses

Think back to a time you were in a nightclub.

They are dark caves, but instead of silence punctuated by the echo of solemn chants, the air moves to the sound of booms. You can’t hear yourself think. Personal spaces dissolve as you move your mouth close to somebody else’s ears, as your body feels the warmth of other bodies, as the gentle touch of a stranger’s hand becomes intimate while you look into their eyes.

The flashing lights blind your eyes and paint a blurry impression of people’s faces. The blackouts and lightsparks with the beat of stroboscopic light are like juxtaposed snapshots of reality, veiled by smoke and foam. Alcohol and drugs melt senses and social codes into a jungle where rules are suspended and forbidden instincts are unleashed.

In some extreme cases, even more senses are saturated, as you submerge your body into the warm water of bath clubs or the dust invades every inch of your skin at a Burning Man rave.

So cathedrals are places designed to show their creator’s opulence and power, but they’re also designed to alter our senses, to throw us into alternate worlds, so that they can open us our minds to change. If that’s the case, what will these places be in the 21st century?

That’s what we’re going to explore in this week’s premium article.

The Peace of Westphalia in 1648 marks the end of religion as the main power in Europe, substituted by states.

“Ecclesiastical” means “related to the Church”.

The ideas entering people’s brains

There is a small but symbolic missing, the Sagrada Familia in Barcelona. It could be that its completion by now... we don't really know, but it could mark a turning point in architecture, a return to decoration after a long period of buildings that were far too refined.

Nice piece. More impressive than cathedrals themselves is the process of cathedral building, which spans generations, technologies. I’ve led to Wikipedia as a 21st-century cathedral of knowledge. https://revkin.substack.com/p/why-wikipedia-works-even-for-climate