Do Masks Work?

Recently, I stumbled upon some chatter against masks, and I thought it would be useful to dive into it for a couple of reasons:

Should we update our beliefs?

What can we learn about knowledge1 from this debate?

This article encapsulates the debate:

Here are some choice quotes2:

The most rigorous and comprehensive analysis of scientific studies conducted on the efficacy of masks for reducing the spread of respiratory illnesses — including Covid-19 — was published late last month. Its conclusions, said Tom Jefferson, the Oxford epidemiologist who is its lead author, were unambiguous: “There is just no evidence that masks make any difference,” he told the journalist Maryanne Demasi. “Full stop.”

But, wait, hold on. What about N-95 masks, as opposed to lower-quality surgical or cloth masks? “Makes no difference — none of it,” said Jefferson.

When it comes to the population-level benefits of masking, the verdict is in: Mask mandates were a bust. Those skeptics who were furiously mocked as cranks and occasionally censored as “misinformers” for opposing mandates were right. The mainstream experts and pundits who supported mandates were wrong. In a better world, it would behoove the latter group to acknowledge their error, along with its considerable physical, psychological, pedagogical and political costs.

This is not the only piece that makes similar claims. Why is this debate so contentious? What does the science say? I wrote a Twitter thread on this that went viral.

But twitter threads are not a great way to be nuanced. This article is an in-depth and nuanced look at the studies, along with some criticism of my take, and my takeaways.

Jefferson et al. Main Results

This is the study that the articles reference (long version here).

This is a Cochrane systematic review. This is a strong point, as systematic reviews take in much more data, and the fact that it’s Cochrane reduces many of its potential biases. And it keeps results from 78 studies. Impressive!

Now let’s look at the studies themselves. The first thing I note is this:

Only 6-7 studies will be highly relevant, because before the COVID pandemic, masking awareness and education was too low for people to take them seriously, or for scientists to have enough quality data. Their following sentence probably suggests this is a reasonable bias:

Additionally, this Cochrane meta-analysis looked at the impact of many NPIs (non-pharmaceutical interventions), including masks, washing hands, and similar things. The actual number of studies that refer only to masks and were released after COVID had erupted is just two: a Bangladeshi one (Abaluck 2022), and a Danish one (Bundgaard 2021).

If we look at these two studies, what is the takeaway?

The Relevant Studies

Abaluck et. al. 2022

The Bangladeshi study looked at 350,000 people. It distributed masks, trained the population, got support from community leaders, and reminded people about the importance of masks. This increased proper mask usage from 13% in the control to 42% in the treated villages early on, and then this difference shrunk over time, but it was always at least 10 percentage points higher in the treated villages than in the villages without any intervention. The number of COVID cases in these trained villages went down by 12% after controlling for other factors, and it was statistically significant3.

This is reasonable:

Masks don’t work standalone. Properly wearing masks is what reduces infections. So they made a huge effort to increase proper mask wearing.

Masks have community-level effects. So you can’t really test individuals. You need to test communities. Nobody else has ever done this for COVID masks as far as I know.

It’s conservative. In the treatment group, only 42% of people wore masks properly, so the 12% is an underestimation of what masks could achieve.

What this is telling you is that masks that are properly worn (at least somewhat reasonably) do reduce the odds of getting infected4.

Bundgaard et. al. 2021

Bundgaard 2021 was a Danish study during the height of COVID in April and May 2020. That said, this was during lockdowns, so there were few infections. This reduces the statistical power of the study.

They trained 5,000 people to do social distancing, and randomly told a group to also wear masks (and gave them free masks) and didn’t do it for a control group. This was clever, as it also controlled for “any intervention” (all people had an intervention that included at least telling them to do social distancing). COVID infections were lower by 18% in the group wearing masks (and by 42% when looking at non-flu/COVID respiratory viruses). None of these were statistically significant, so we should not weigh this study too much, but it adds some valuable info.

These suggest masks work, right?

Why Do We Disagree Then?

What this means is that all the other studies from before COVID probably saw on average no impact of mask wearing, or even negative.

Their results about masks vs no masks are summarized in this table:

This is a bit intimidating, so we’re going to break it down. You can see three sections (1.1.1, 1.1.2, and 1.2.3), with studies measuring:

Flu/COVID-like illnesses

Laboratory-confirmed flu or COVID

Lab-confirmed other respiratory viruses

We recognize our two preferred studies, Abaluck (Bangladesh) and Bundgaard (Denmark). Bundgaard, interestingly, is the only study that looked at lab-tested non-COVID/flu respiratory viruses (3rd section), and saw a whooping 42% reduction in them—albeit with small numbers, so we should take it with a grain of salt.

So which ones of these other studies should we pay any attention to? We can tell by the column titled weight. I interpret this5 as how much weight the authors of the review put on each study when they combined them. A weight of 50% means that the risk ratio6 of that study counts for 50% of the total risk ratio.

What we can see is that there are two other relevant studies: Aiello 2012 and Alfelali 2020. Together with Abaluck and Bundgaard, they account for 87% of the weights in this section about masks vs no masks. OK, let’s look at them!

Alfelali 2020

Some interesting facts about this study:

It's from 2020, but it looked at data from 2013 through 2015, so that’s not great in my book.

It only has 7,700 subjects. This is not a lot. If 1% of people get infected, that’s just 77, or about 38 per group. Just a random variation of 5-6 people would completely throw off your results.

The subjects were Hajj pilgrims who were given free masks to wear over four days, along with instructions. The pilgrimage to the Hajj is usually five to six days as per the study.

They counted that a person wore a mask during a day if they wore any mask during that day! Even for one hour.

The control group got nothing, so there was no control for “any intervention”. What produced the results? Was it the masks, or the fact that somebody talked with these people?

They then tested all these people with PCRs, and didn’t see a positive impact. The opposite: People with masks appeared to have gotten 40% more infections.

So what was the conclusion of the study?

This sounds reasonable to me. Imagine you’re a pilgrim to the Hajj.

It’s pre-COVID, so nobody had much education about masks, their importance, how to wear them…

You might have social pressure against wearing them: Why is this guy wearing a mask, is he sick?

More importantly, it’s not right to cover your face:

Keeping your face uncovered is a part of the "ahraam" (dress code for Hajj) as applied by most Muslims. If you breach the protocol you have to pay a penance. So highly unlikely that pilgrims followed protocol at all.—Mansoor

You spend a full week with millions of other pilgrims, sharing everything, in close quarters, under the heat and the pressure of other people.

How well will you wear your masks?

So the authors of the study disregard their results. But our Jefferson et al. study doesn’t! They take it at face value! Under what world do you look at these results and conclude: “Yep, masks probably increased infections by 40%”?

The latest hypothesis about this is that people get overconfident wearing masks. But… Did these Hajj pilgrims really get overconfident wearing masks? What did that make them do… hang out with even more pilgrims?

What this study really did was to prove that giving away masks to people without any other training, in hardcore situations, and against public customs won’t reduce respiratory virus infections. That sounds reasonable to me.

Aiello 2012

The Aiello study was on 1,200 students across several campuses in 2007-2008. Not so great: an old study, with a few 20 year old students, who probably didn’t care that much about masks. Here were the results, from the abstract:

A significant reduction in the rate of flu-like illnesses was observed in weeks 3 through 6 of the study, with a maximum reduction of 75% during the final study week. Both intervention groups [masks and masks plus hand-washing] compared to the control showed cumulative reductions in rates of influenza over the study period, although results did not reach statistical significance. Face masks and hand hygiene combined may reduce the rate of ILI and confirmed influenza in community settings. These nonpharmaceutical measures should be recommended in crowded settings at the start of an influenza pandemic.

In other words, this bad study supports mask mandates!

If you look into the details, it does look like the study saw an increase in infections in the masked group:

Why, then, the discrepancy?

It’s extremely non-statistically significant: 0.52 when it should get at least to 0.05.

This comes from the fact that there were a grand total of 31 people ill in the masks+handwash group, 46 in masks only, and 51 in the control. About a third of that after doing PCR tests. In other words, just a handful of people more here or there (very reasonable with chance) would completely throw off your results.

When paired with hand washing, the drop in infections was high and more significant (still not a lot).

These college students wore masks for less than 2h a day.

Every statistically significant result (those with a little “e” to their right) show a positive impact of masks (with handwashing). Those are disregarded.

When looking at lab results instead of illness, results are the opposite.

Why Do We Disagree?!

Why do we disagree then? What is going on?! How can you base a meta-analysis on a gazillion studies, of which only four studies are relevant, one is self-described as inconclusive, the other three support that masks work—of which one is huge and highly relevant—and yet conclude that masks don’t work?!

So I went back to the table with weights:

OK so here’s what’s happening:

First section: flu/COVID-like illnesses

They give a weight of 41% to the Bangladesh study. They then give the same weight of 41% to the terrible studies of college students and Hajj pilgrims! Despite the Bangladeshi study:

Having 40x more people

Is post-COVID

Included a control for “any intervention”.

Very surprising.

Here’s what the Jefferson et. al. scientists had to say about the low weight of the Bangladeshi study. Explains a lot:

This accounting magic throws the probability of mask protection to a range between -16% to +9% infections, which means “The impact is so low that it’s not different from chance. Yeah, you counted 1,000 college students and 8,000 pilgrims from 15 years ago with the same weight as a fantastic megastudy of 350k people…

And we’re not done. Now look at the 2nd section.

Second section: lab-confirmed flu/COVID

The average risk ratio there is 1.01, which implies masks increased flu/COVID by 1%. Infection protection ranges from -28% to +42%.

How is that possible?

They don’t count the Bangladeshi study! Because it didn’t measure infection with PCR tests… But of course! Because it had 350k Bangladeshis in it!

Meanwhile, the Hajj and college students studies weigh over 50% of this result!

And the Danish study only 27%. Incredible!

This is especially outrageous, because the Hajj study resulted in a 40% increase in the measurement of flu. Do we really think that the masks increased these pilgrims’ chance of catching a respiratory virus by 40%?! I might be biased, but I can’t conceive how a reasonable human being would reach that conclusion. But that’s what they put in their study! Unashamed, they mark down a +40% infection rate for mask-wearers. Wow. Take that out, and the results of the entire Jefferson et al. study flip.

But we’re not done! They’re also adding another study, MacIntyre 2009, with a weight of only 6.6%, but which recorded an increase in infections of 150% with masking. It single-handedly flips the results, from a -10% reduction in risk rates with masks, to +1%. Wow, what happened? How did masks increase infections that much! I WANT TO KNOW!

Let’s look into it.

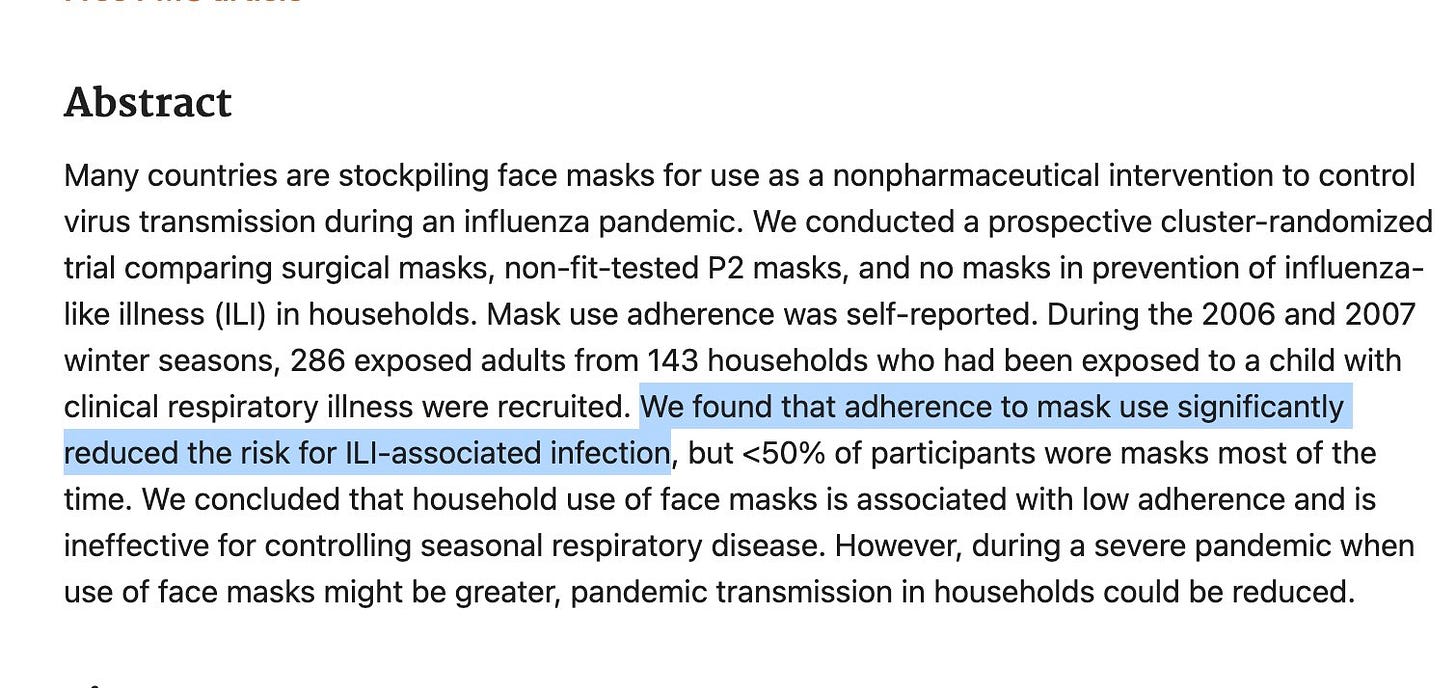

MacIntyre 2009

This study is a 2006-2007 (!!) study of 286 ppl (!!!) in the Australian healthcare milieu, where a grand total of 17ppl (!!!!!) were infected, and where, as far as I can tell, masks were overall good?

We found that adherence to mask use significantly reduced the risk for infections associated with influenza-like illnesses.

Wow. These are true magicians! They took a study that claims that mask adherence significantly reduces the risk of influenza-like illnesses, and then twisted it to say masks increased risks by 150%! But where do they get that figure? Thankfully, a Twitter reader gave me the tip:

You got to read the table to appreciate it:

In other words, if five people in Australia 15 years ago would have tested positive instead of negative in a pretty poorly designed study, the entire Jefferson et al. analysis would be flipped.

But this still doesn’t explain why their numbers are opposite the study’s own conclusions. You need to dig deeper… It turns out the study authors also asked for mask compliance. They then controlled for that, and looked at what happened to the infections of those properly wearing masks. Here’s what they found:

Proper masks reduced infections by 74%! And this result is the one statistically significant number in the study! But the authors decided to disregard it. Why?

I’m guessing the logic: “When you’re looking at whether masks work, you have to also consider adherence. No adherence? Masks are worthless.”

But this logic is circular! Yeah, if you tell people that masks don’t work, they will not use them properly! How can you ignore evidence showing that masks, properly used, do work?!

The lead author of the MacIntyre 2009 study, Raina MacIntyre, has an opinion on this.

Talking about masks, she thinks there’s “overwhelming evidence they work”. About the Jefferson et al. study:

The Cochrane review combined studies that were dissimilar — they were in different settings (healthcare and community) and measuring different outcomes (continuous use ofN95 vs intermittent).

This is like comparing apples with oranges. If wearing N95 intermittently doesn’t protect but wearing one continuously does, then combining studies that use it in these different ways may suggest N95s don’t work.

I reached out to her to see if she has any further opinion on the Jefferson et al. use of her study. I’ll get back to you if she responds.

Why These Weights?

This begs the question: Why did the researchers use these weights?

Apparently, they used an inverse-variance weighing method. This is a statistically accepted approach for combining studies, but it will work better for some situations than others. A situation that I think it’s very poorly adapted to is one where a single study is much bigger than smaller ones—exactly our situation7.

This obscures the more important point though: Why would you give any weight to poor studies like the Hajj one, where even their authors say the study didn’t test what they intended to test? As Alex Siegenfeld explained in this study:

The studies that did not find statistically significant effects prove only that masks cannot offer protection if they are not worn.

Summary

Summarizing, this is what they did:

They took a lot of studies, so it looks like there’s a lot of them (78!), with a lot of people (over 600k!).

For masks, only five studies really matter.

There’s the amazing Bangladeshi study, which is the really good one.

That Bangladeshi study accounts for more than half of all the people in all the other 77 studies, but somehow only accounts for 40% of the weights of one of three sections.

They add a Danish one, which sounds good.

Then they take two studies (college students and Australian healthcare) whose authors claim their studies support masks, and use their data in a way that contradicts they authors’ conclusions, even if it’s logically unreasonable, since proper mask usage was probably extremely low.

Then they add a another study (the Australian one), where they disregard the one statistically significant result they had, but use instead one that is not statistically significant, doesn’t control for poor mask usage, and hinges on 5 people not getting sick.

You could take these last three studies and completely disregard them. Or give them a very very low weight. But that’s not what they do. Combined, their weight is higher than the weight of the Bangladeshi study! From what I can tell as of now, this is because the statistical method they use to weigh these studies is biased towards smaller studies8.

The authors create three sub-sections to treat masks, suggesting that each section is equally useful, when in fact two are not statistically significant. The only one that matters is the one that takes into account the Bangladeshi study. That one shows a positive mask impact, and it would be statistically significant if the Hajj and college students studies were disregarded.

When we say there are lies, damn lies, and statistics, this sounds like a prime example. The authors don’t make up data. But data is not reality. Data is messy. Transforming data into insight is hard, and requires choices. If these choices are biased, so will the result be. Here, the bias is at several levels:

Picking some data and not other, as in the MacIntyre 2009 study.

Taking into consideration studies that shouldn’t be, like the Hajj study.

Splitting the results into three sections to muddy the results of the only strong one.

Using an inverse-variance weighting method, which likely penalizes bigger studies.

Taking these muddy results, and making bombastic statements about them that contradict the study itself.

For me the issue is not as much the bias. Bias is human. We need to account for it.

It’s the confidence. Data is hard. We need to simplify it and make it clearer to the public. But not with overconfidence. This is not how science works, and it’s not how society should work.

I hope you enjoy this article. If so, click on the Like ❤️ button, it helps to get it discovered by others on Substack. Even better, if you think anybody can benefit from reading it, please share it with them. It helps grow this newsletter, and it helps me dedicate more time to it.

In this week’s premium article, I will look at the criticisms of this article and tweets, as well as go in depth into the biases part. Later this year, I will rate my COVID predictions from a year ago. Subscribe to receive these articles if you haven’t yet.

If you want to read more about this study’s biases, you can go to this article.

More precisely epistemology, but it took me over 30 years to understand that word, so I assume most people are in the same boat as me.

I always lightly edit quotes for understandability. My goal is to make the quoted person look better.

Which means it might be more or less than 12% in reality, probably between 6% and 19%, and it’s very likely that it was more than 0%.

The 12% is not huge, but it exists, it’s good, and remember that only 42% of people adhered to proper mask usage. It’s in the poor mask usage moments that infections tend to spread, inflating infections for mask wearers.

The study is over 350 pages so I don’t have time to read it all… And neither should the vast majority of people who are not working on this full time. Looking at Twitter’s response to my thread on the topic, it looks like I’m among those who’ve made the deepest reviews of this meta-analysis, which is scary. Has anybody read that study front to back?!

The comparative risk of wearing masks or not. A risk ratio (RR) of 1.21 means mask wearers are 21% more likely to get infections.

I’m still looking into this, and will have an update to this in the premium article.

Again, I am confirming this.

I seldom really learn from a blog or podcast, but in the case of Tomas Pueyo every encounter with his thinking has been memorable. Thanks Thomas.

I read the article in the NYT with interest and shared it with my sister (MD) and daughter (grad student in public health), and we were very puzzled. The conclusions and headlines didn't make sense or feel right. I shared your write-up, and it answered a lot of our questions.

I really appreciate the work you have done here and wish the NYT would have been more careful before giving the author such a public platform.

Bravo and thank you!

And this is one more example of the truly excellent work you do.