How Can Vertical Farms Become Viable?

This article was for last week. This week or next I’ll take my 2nd week off of the year.

Earlier this week, we discussed the promise of vertical farming and its main shortcoming: Right now, it costs too much. Specifically, the average costs of energy and labor are too high compared to those of water and land, which are vertical farms’ strength since they don’t waste any.

That’s why critics highlight how investments in vertical farming have crashed:

Critics also point out how so many vertical farming darlings have either laid off workers, shrunk operations, or simply shut down.

One of the biggest players, AeroFarms, had raised hundreds of millions, but then declared bankruptcy and only recently emerged from it with a much narrower scope. Like AeroFarms, Kentucky’s AppHarvest, Florida’s Kalera1, Pennsylvania’s Fifth Season, Detroit’s Planted, New York’s Upwards Farms2, and France’s Agricool all filed for bankruptcy.

Another one, German InFarm, which had raised $600M, closed its operations in nearly all its European markets.3

Bowery reached a valuation of $2.3B in 2021, but that valuation had gone down to $350M by the end of 2023 and it went through two rounds of layoffs after that.

But at the same time, vertical farming is projected to grow at 25% annually over the next few years, and the industry is thriving in some areas. How is that possible?

Playing to Its Strengths

Vertical farming’s weaknesses are energy costs, labor costs, and initial investments.

So it’s not a surprise that so many companies went down after Russia invaded Ukraine and the cost of energy soared—especially in Europe. Something similar happened with initial investments.

Initial Investments

It’s not news that investments in vertical farming shrunk in 2022: All tech investments shrunk then.

When it costs nothing to get a loan, companies that burn cash today promising lots of money tomorrow are going to borrow like crazy. But if suddenly it costs 5%-10% to borrow, it becomes so much harder.

That’s what happened to all tech, vertical farms included. Indeed, setting up a vertical farm is not cheap, as you need to make the upfront investment of the stacks, lighting, heat, cooling, sensors, water management, nutrient management…

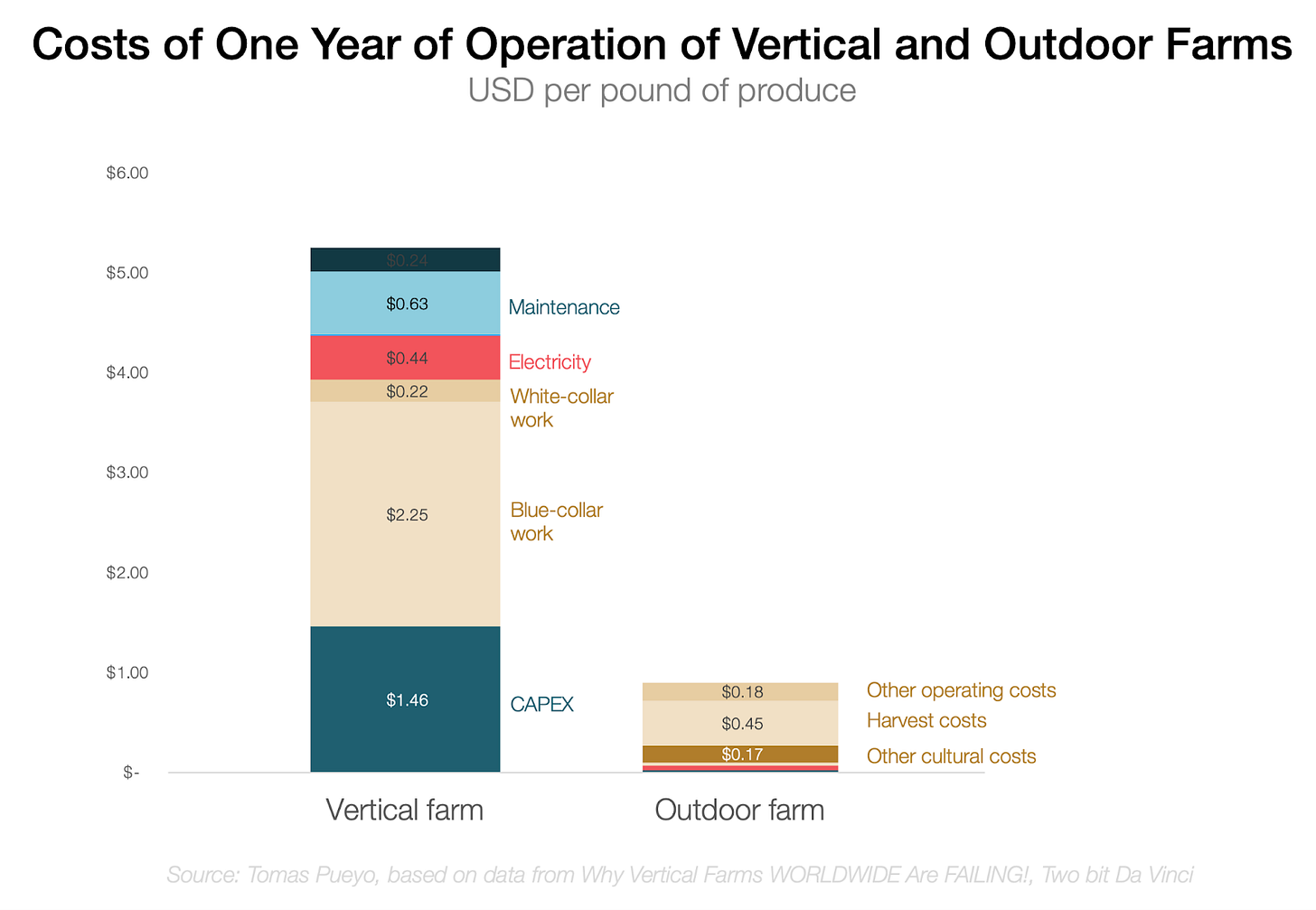

I didn’t mention vertical farming’s fixed costs in my previous article,4 but I found another comparison of costs that includes them.

I can’t find the original source for this data, and it’s highly suspicious that land and water don’t appear, so I would take this with a major grain of salt. The only point I’d take is that the initial investment and maintenance are major sources of costs, so it’s not surprising that investment in vertical farms would go down when interest rates go up.

By nature vertical farms will blossom on sunny days of low interest rates and wither in harder times of higher interest rates. That will be true until their setup costs are low enough. That’s exactly what happened to solar panels and batteries. The same will be true here.

Early Adopters

In all new industries, businesses start serving specific niches before going mainstream. These niche customers care less about costs but really value what new entrants have to offer.

A good example is Tesla: They started with roadsters because rich people didn’t mind spending $200k on a car, as long as it made them unique. Then, Tesla released the Series S, which was still expensive, but less so. Only later did it release the mass-market Series 3. Each car allowed the company to learn how to make better cars and lower production costs.

If we apply that logic to vertical farms, what types of customers will fill the first niches? They will be those where energy and work are cheap, but water and land are expensive. If only there were deserts in the world with plenty of cheap energy and human labor…

And another:

Water is much more expensive in deserts, so it makes sense that vertical farming is succeeding in rich places like Saudi Arabia, the UAE, and Israel. Saudi Arabia is an especially ideal market because it combines expensive water with cheap energy (oil) and cheap labor (lots of South Asian immigrants).

For a country like Israel, the other advantages of vertical farming besides expensive water are lots of high-quality technical workers, and a strong strategic goal for the country of becoming self-sufficient for its food.

Vertical farming is also big in Japan, but for another reason: Water might not be scarce there, but technical expertise is available and affordable, and land is very expensive since there are so many people packed into such limited living space.

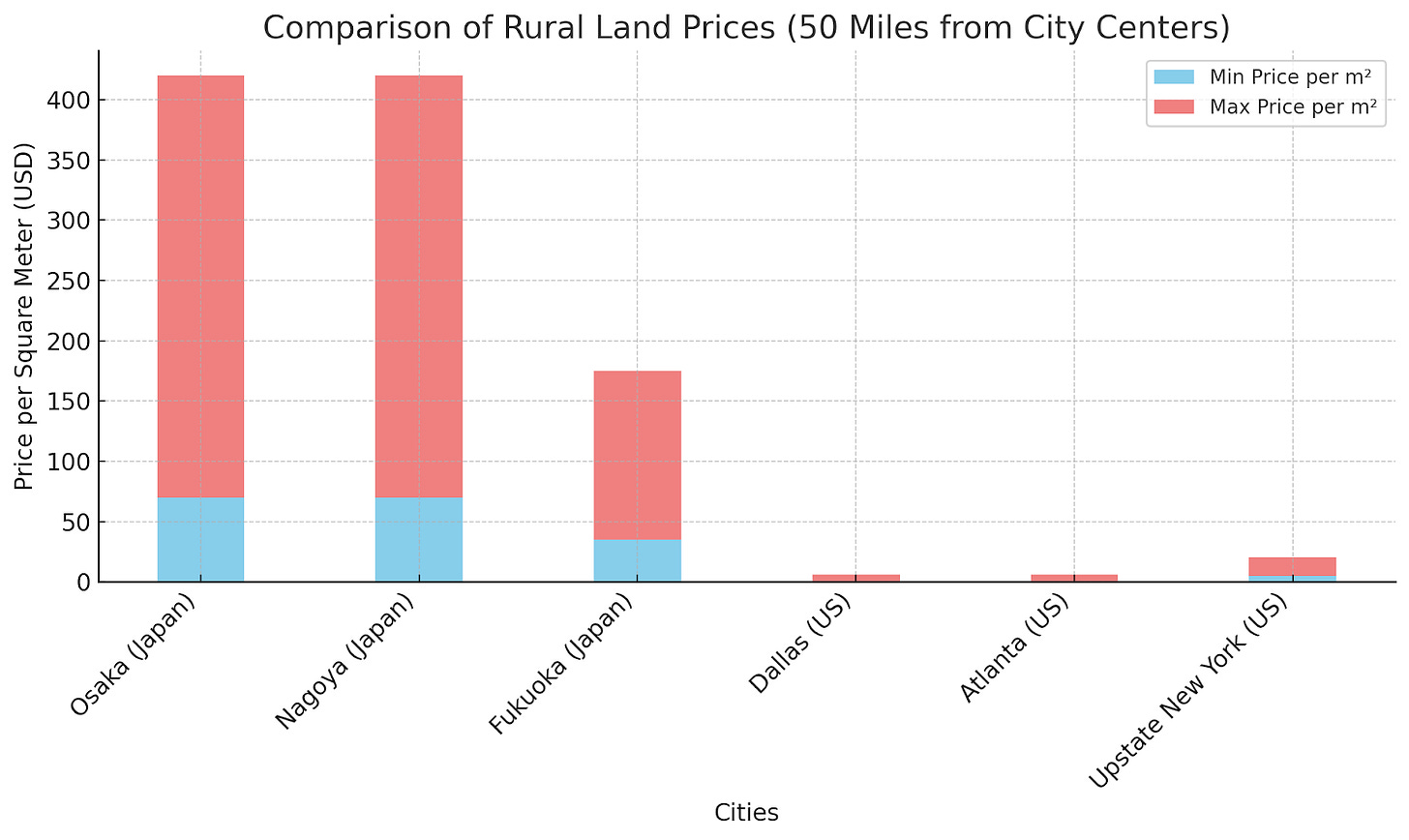

I asked ChatGPT to compare land costs in the periphery of Japanese and US cities and this is the result:

Conversely, Japanese construction is very cheap compared to the US, so building vertical farms in Japan might be much cheaper than in the US.

That might be why Japan’s Spread has built TechnoFarm, a profitable vertical farm that can produce 10 tons of lettuce per day, which is about 100x more per m2 than in outdoor farming. They achieved that by automating 70% of tasks, reducing workers by 50%, and using 97% less water than outdoor farming and without pesticides.

Another factor besides costs is revenue. Places near big markets that pay a huge premium for fresh produce are also good targets for vertical farms. It’s not a coincidence that England5, Japan6, Singapore, and the US Northeast (near New York) have seen many vertical farming startups.

Countries like Singapore, Saudi Arabia, or the UAE have an additional motivation: strategic independence in their food supply.

The UK, Nordic countries, and Canada can hardly grow their own vegetables year round because they’re too cold and dark. Vertical farms provide them with fresh produce, otherwise hard to get given long-distance transportation from growing areas.

By starting with these specific markets (deserts, dense places, places with cheap energy, places good at automating, places near big urban markets, countries that care about food supply independence), vertical farms can become profitable earlier, which then funds R&D to further automate processes and increase their yield to gain more markets.

Where exactly will these vertical farms place themselves?

Far enough from city centers to take advantage of cheap, rural land prices

Close enough to city centers to minimize transportation costs

As close to existing distribution centers as possible

We do want to be within striking distance or even adjacent to distribution centers because we need labor, we need access to trucking lanes and we need efficiency in terms of land. That’s why our future plans dictate that we will be in and around distribution centers across the United States.—CEO of Eden Green

So that’s for geography, but there’s another type of niche that vertical farms can start with in order to become viable fast: certain plants.