How Silver Made Chinese Empires

And Unmade Them

In the previous article, we saw how China exported goods like silk, porcelain, and tea to the West for thousands of years without wanting other goods in exchange. They were content receiving just money in exchange. Remember this from that article:

From 1500 to 1800, Bolivia and Mexico’s mines produced about 80% of the world's silver; 30% of that eventually ended up in China!

But why? Why spend so many centuries manufacturing stuff to only get money in return?

The Chinese government’s obsession with money is thousands of years old, and for good reason. Unique pressures pushed the Chinese to first use shells as currency, then invent the first coins, the first paper money, move to silver, back to paper money, actively drive trade surpluses to hoard silver, and eventually cause the direct fall of at least two empires. What were those pressures? Why did they affect China so much?

That’s what we’re going to explore today.

What Makes a Currency Good?

The first currency to be widely used in China was cowrie shells.

Cowrie Shells

Shells have some positives:

They’re durable, so your money is not going to break into pieces.

There’s not an infinite amount of them: If people just used stones, anybody could create money and that money would be worthless.

They look broadly the same, there’s not a massive difference between two shells that would grant a higher price for it.

They’re reasonably easy to transport from one place to another.

But also some negatives, like for example:

You can’t divide shells into smaller pieces (if you break them, they’re just useless broken shells), or aggregate them into bigger pieces.

Shells were obtained from very far away, which made it hard for new shells to reach China, and this meant instability: What if for a long time no shells arrive? The economy grinds to a stop.

If some very entrepreneurial person figures out a way to harvest tons of shells, they can instantly become rich, but the massive amount of shells injected into the economy means suddenly people wouldn’t accept them as currency. Why would you sell your hard-earned wheat for some shells when there are millions of them entering the market?

Here, we’re starting to see that a good currency has some important features:

1. Availability

You must have enough currency for everybody to buy and sell stuff with it. If it’s not widely available, people will hoard what little there is to store their wealth, and the currency will become even scarcer. At some point there won’t be enough circulating for people to buy and sell, and they’ll have to resort to bartering, debt, or alternative currencies, all of which severely impact trade, and hence, the economy.

For example, when the Romans left Britain, the supply of bronze, silver, and gold money disappeared. Over time, the local economy lost the currency it needed to function, and people had to fall back to bartering or keeping track of debts for their exchanges.

2. Scarcity

Conversely, too much currency is also a problem. If it’s too easy to produce, you’re going to have counterfeiting and hyperinflation. So a currency needs to have just the right amount of scarcity: not too much that it’s rare, but enough that it’s not flooding the market. This usually means that supply must be controlled or be naturally scarce to prevent inflation, loss of value, or hoarding. Often, this also means it must be backed by an issuing authority (central bank) with credible monetary policy.

For example, paper money is easy to print for anybody who has a printer, so historically, paper money can be counterfeited, and this fake money can flood the market. More commonly, the government can overprint money, making it worthless. This has happened in virtually every hyperinflation of the last century or so, and some argue that it’s happening today with dollars. As we will see, this was crucial in China’s history.

3. Stability

A key feature of currency is that it can convey the price of goods over time and space, so that you know the equivalence between one good and another, like how many kg of wheat are equivalent to a cow. But for that you need the currency to be stable: If its value fluctuates wildly, you won’t know the cost of every good, and this will make people nervous, either hoarding the currency or getting rid of it as fast as they can. It will undermine the currency’s role as a store of value or unit of account.

This is one of the concerns about Bitcoin as a currency: Its value swings widely.

4. Divisibility

What if your gold coin is worth one pig, but you just need one chicken, which costs maybe a quarter of a gold coin? If you can easily cut the gold coin into 4 pieces, it will be more valuable than if it must remain intact.

So for example, shells were not great currency because they were not divisible: If you break them, you can’t put them back together, so the value simply vanishes. Meanwhile, you can cut a piece of metal in two, and still have two halves. You can mint them into a new coin if you want. Metal’s divisibility is good.

5. Durability

If your money can break, oxidize, or simply disappear, that’s not good money. It must be durable.

That’s why paper money was bad, as notes could break easily, even just by getting wet. Same thing for shells, which could shatter or be crushed. It’s also why perishable food is a horrible currency, and why grain could be used as currency more easily than fruit.

6. Portability

A currency must be easy to carry or transfer. If it’s too heavy or voluminous, you can’t easily move it around.

This is one of the big drawbacks of metal money, and why metals like gold, which were more valuable per gram, were preferable to others like iron: Iron is not scarce, so its value is low compared to its weight. Iron also has a durability issue: It rusts, while gold doesn’t.

7. Fungibility

Currency is fungible when each unit is identical in value and interchangeable with another of the same denomination (e.g., one $10 bill = any other $10 bill).

Imagine a time when people had to handle coins of different metals, sizes, and weights. They had to weigh each coin and value each coin differently, dramatically increasing transaction costs. If you know that every coin is exactly the same, you can just look at them and know how much value they represent.

8. Acceptability

Effective currency is universally accepted within the economy where it circulates. Usually, that means it’s backed by trust, government decree (fiat), or intrinsic value (e.g., gold).

People accept US dollars around the world because everybody else does, and because the US government says: “I accept dollars as a way to pay me, and I will forever.” People trust the US will be around for a long time. But many don’t accept Bitcoin or Ethereum yet, simply because others don’t, either.

So why did the Chinese obsess over silver so much? How did they end up prioritizing that type of currency over all others?

Chinese Currency Transitions

Shells

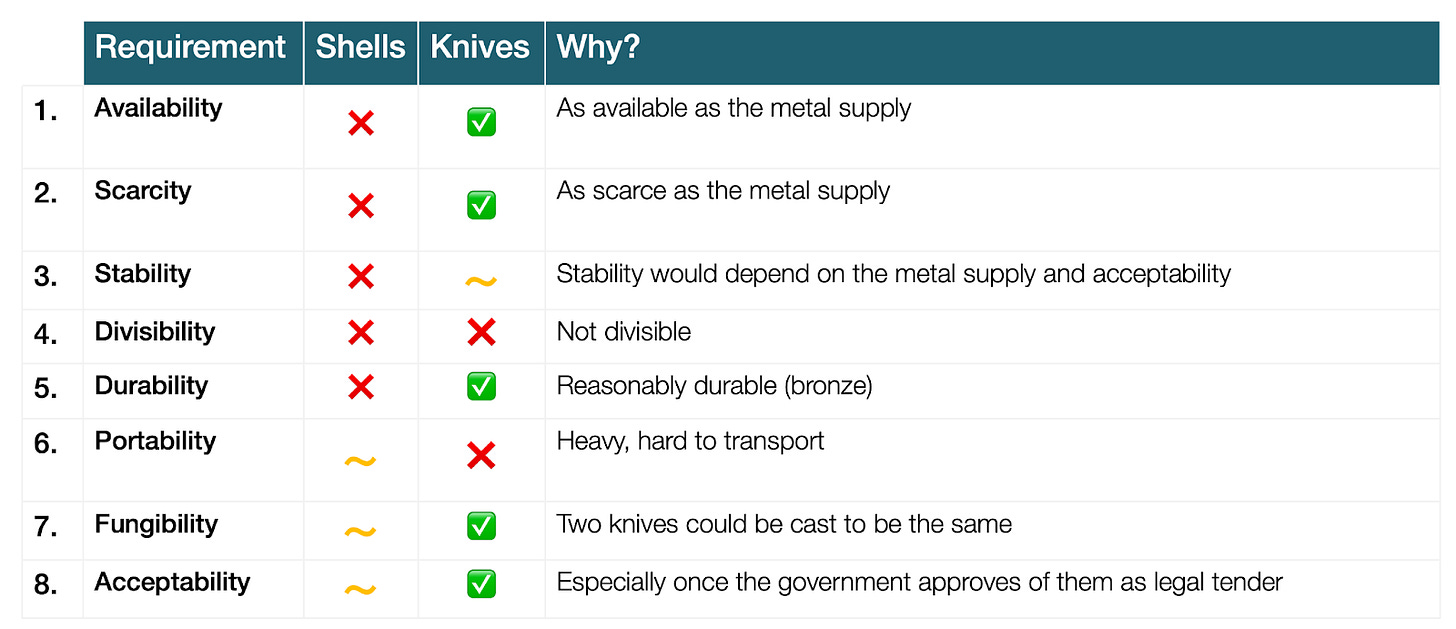

According to our factors, shells are not that great as currency:

Since China has always had a huge population, which grew earlier there than in most other regions, it quickly needed a better alternative:

The solution was… knives!

Knife Money

It’s unclear how knives became money. My guess: Knives were intrinsically valuable, and unlike shells, they were available (there are knives around, and more can be made as long as there’s metal), scarce (there aren’t infinite amounts of metal), and durable (especially if they were made of bronze). Once people started using them as a means of exchange, they standardized them, making them fungible, and eventually knives as currency became acceptable and stable, too.

The problem is that they were not divisible and were hardly portable.

Low portability came from the weight of the bronze. As for divisibility, bronze is divisible, which made it a reasonably good metal to use, but bronze in the shape of a knife was not as divisible.

So the obvious next step is to replace knives with something:

More portable

More divisible, which means different sizes representing different amounts of money. That way small and big transactions can be facilitated with different denominations.

Enter cash coins.

Cash Coins

Cash coins could have different standardized sizes to represent different amounts of value, solving the knives’ main issue of divisibility. The standardization and centralization of supply is important, because then you can know the exact amount of precious metal you are getting in a coin. If you have coins of different sizes and different purity, you lose this.

And of course, many of the coins were smaller than knives, so they solved the problem of portability for small transactions.

You’ll notice that they have a hole in the middle. Why?