Silk, Porcelain, Tea, Opium: 2000 Years of Trade Deficit with China

And how that determines the China of today

Westerners fear their chronic trade deficits with China: How long will they last? What happens when the West owes China so much they can’t repay the debt? How should we understand the current trade war between the US and China?

What we don’t realize is that this isn’t the first time this has happened. We need only look at History: The West has had deficits with China for over 2,000 years, and they have had a massive impact on world history, from the opening of global trade routes, to the establishment of colonies, colonial policies, international wars, the emergence of nation-states, the politics of present-day China and the US…

So today, we’re going to take a fascinating trip across four commodities that drove the history of the world: silk, porcelain, tea, and opium.

Silk

Here’s how much Romans loved luxury goods:

India, China and the Arabian peninsula take one hundred million sesterces1 from our empire per annum at a conservative estimate: that is what our luxuries and women cost us—Pliny the Elder, Natural History (77–79 AD).

Of these, silk was the biggest import from China. In 14 AD the Senate prohibited the wearing of silk by men!

To pay for it, Romans traded glassware, amber, wine, carpets, and other goods,2 but they didn’t make up for the value of what Romans bought from China. And in general, Chinese traders preferred money—mostly gold and silver—over other goods. Here’s the chronicler Solinus, writing in the 200s AD about the Silk Road:

From the beginning of the [Caspian Sea] coast, we found deep snows, long deserts, cruel people and places, cannibals and the most terrible wild beasts, which make this half of the road practically impassable. After [...] crossing vast uninhabited regions, the first people we hear about are the “Seres” [Chinese]; they sprinkle water on the leaves of certain trees, to make them humid so to produce a substance that will turn into skeins similar to cotton. This is called “sericum” [silk], which we know and use, which awakens a passion in women for luxury, and with which even our men dress now, leaving their bodies on display.

The “Seres” are civilized and peaceful people, but avoid contact with other people, refusing to trade with other nations. Every time they cross the river and out of their country to do business, they do not use their language, or talk; they make an estimate with a look, and stipulate a price. They prefer, by the way, only to sell their products, but do not like to buy our goods.3

The European and Middle Eastern appetite for silk was so huge that Europeans obsessed about producing silk locally, but they didn’t know how to make it and didn’t have silkworms: China had protected its near-monopoly on silk for many centuries thanks to imperial orders to execute anybody caught trying to export silkworms or their eggs. The only way to succeed was by stealing them, and that’s precisely what two Christian monks did around 550 AD, risking their lives to smuggle silkworms hidden inside their canes.

This started silk production in the Eastern Roman Empire, which would slowly permeate through the rest of Europe.

This might have been the first time Chinese manufacturing prowess caused a trade imbalance in the West that required political intervention, but it wasn’t the last.

Porcelain

It’s not a coincidence the English call porcelain “china”.

The Chinese had been perfecting porcelain for thousands of years to make it thin, strong, and resonant. No other civilization could replicate this for a very long time.

But porcelain could only start reaching Europe in the 1500s,4 which is not a coincidence either: Porcelain was too heavy and fragile for overland routes, so it needed a maritime route to reach Europe. The Portuguese found a path to the Indies circumventing Africa just around 1500. It was very much their goal to bring back luxury goods to Europe, after the Ottomans had conquered Constantinople in 1453 and closed the Silk Road to Europeans.

Chinese porcelain was so much thinner, whiter and more translucent than local wares that European nobility really prized it. Its high price and scarcity were a core part of its success, too, as it gave its owners status. The most famous was the white and blue porcelain:

But there were many types, and European nobles loved hoarding them.

Of course, the high price porcelain commanded became an incentive for Portuguese merchants to increase its import. The Dutch copied them and started trading porcelain with China, too. Soon followed the English, the French, and even the Swedes—any European country with access to the Atlantic, really. Spain did the same, but via the Pacific Ocean.

Here’s a fascinating detail: You know how nowadays Westerners design some products and then they send those designs to China for manufacture?

Porcelain is another example of China manufacturing products that Europeans craved, but again it didn’t need anything Europeans produced. Except for silver. So silver flowed from Europe to China. From 1500 to 1800, Bolivia and Mexico’s mines5 produced about 80% of the world's silver; 30% of that eventually ended up in China!

Europeans hated that flow, as the silver disappeared as fast as it was produced, so they tried to stop it. Of course, the most incentivized were the countries who didn’t have access to either silver or trade with China. This is why the Italians tried to copy porcelain in the late 1500s with Medici porcelain, although they largely failed. By the early 1700s, Germans succeeded. A few years later, in 1712, the French Jesuit father Francois Xavier d'Entrecolles published the secrets of porcelain making in Europe, which he had read about and witnessed in China. In the following decades, the local production of porcelain increased and the import of Chinese porcelain fell.

Tea

But look at what happened with tea:

It started arriving in Europe in the 1600s, and by the 1700s it had become a craze, especially in Britain and its American colonies.6

The more demand for tea increased, the more its price dropped, and the more people across the empire could afford it and consumed it, which increased the overall British spend on tea.

This trade grew so much that it became a matter of political importance. Remember: It was a tea taxation incident that sparked the American Revolution. From Lewis Dartnell’s book Origins:

The British East India Company endeavoured to supply American demand, but by the late 1760s, most of the leaves consumed in the colonies were smuggled Dutch tea, encouraged by American patriots against British taxation. To undercut the price of smuggled tea, the British parliament passed the Tea Act in 1773. This allowed the company to ship tea directly from China to America, without having to pay British import duty, and granted them a monopoly on the sale of tea in America. The tea was subject to tax only in the colonies. The colonists, however, viewed this as an attempt to foist British taxes on them. They harassed East India Company consignees, refused to accept the tea and left it to rot on the dockside, or prevented the East Indiamen from landing the product. One of the most public–and famous–displays of rebellion flared in Boston Harbour, where in December 1773 protestors boarded the ships and destroyed over 340 chests full of tea by dumping them over the sides into the harbour waters. This Boston Tea Party triggered similar acts of rebellion in other ports, including New York. The situation escalated with parliament in 1774 passing the Coercive Acts–or the Intolerable Acts, as they were known in America–designed to make an example by punishing the defiance of Massachusetts, stripping the colony of self-governance and forcing the closure of Boston Harbour until the ruined cargo had been paid for. But these harsh reprisals only served to unite the colonies against the king, and tensions continued to mount until the War of Independence erupted the following spring.

The Boston Tea Party destroyed China-grown tea bought with Spanish-American silver because of British taxes.

Back in Britain, tea’s ever-escalating trade imbalance with China became a serious economic problem, so much so that the British King George III sent an envoy to the Chinese Emperor to ask for more trade liberalization. These are excerpts of the Emperor’s response:

Our Celestial Empire possesses all things in prolific abundance and lacks no product within its own borders. There is therefore no need to import the manufactures of outside barbarians in exchange for our own produce. But as the tea, silk and porcelain which the Celestial Empire produces, are absolute necessities to European nations and to yourselves, we have permitted, as a signal mark of favor, that foreign merchants should be established at Canton, so that your wants might be supplied and your country thus participate in our beneficence.7

So what did the British do to solve the trade imbalance? Two things. One is that the East India Company sent Scottish botanist Robert Fortune to China to purchase and export Chinese tea plants in the 1850s. This kick-started tea production in India, which grew over the following decades, reducing the share of Chinese tea consumed. Here we have, for the third time, a smuggling of Chinese production know-how to reduce trade imbalances.

The other thing that the British did was introduce opium.

Opium

When the British conquered India8 in the late 1700s, they were very conscious about their trade imbalance with China, so they looked for any way to reduce it. They found the right tool in opium. They devised a plan to produce it in India and sell it in China. So the British drove local farmers in eastern India out of crop production and into poppies, from which opium is derived.

Then, the British introduced opium smoking in China.9

Initially, it was considered a medicine. It was the only available pain-killer. Then, it spread among the cool and rich. From there, it spread to the rest of society. Of course, many of those who tried it became addicts.

It took off.

The Emperor Jiaqing noticed all this so he published an edict to stop it in 1810:

Opium has a harm. Opium is a poison, undermining our good customs and morality. Its use is prohibited by law.

But the government couldn’t enforce it. When the Chinese government finally cracked down on opium in 1839, the opium trade was paying for all the tea trade and then some, so the British reacted to protect the trade and attacked China; this was the First Opium War.

Britain won and bent China's arm: It would be allowed to sell opium in China. It also took over Hong Kong.

There would be another Opium War, after which the British, and then other Westerners10 could reach far inland in China to sell opium. The deficit to China became a surplus. Over the following decades, opium addiction became widespread. By 1949, 4.4% of Chinese people were addicted. Local farmers replaced their crops with opium. Governments used opium taxes to finance themselves, and this lasted until the Communist Party had a strong enough chokehold on society and culture to finally ban opium.

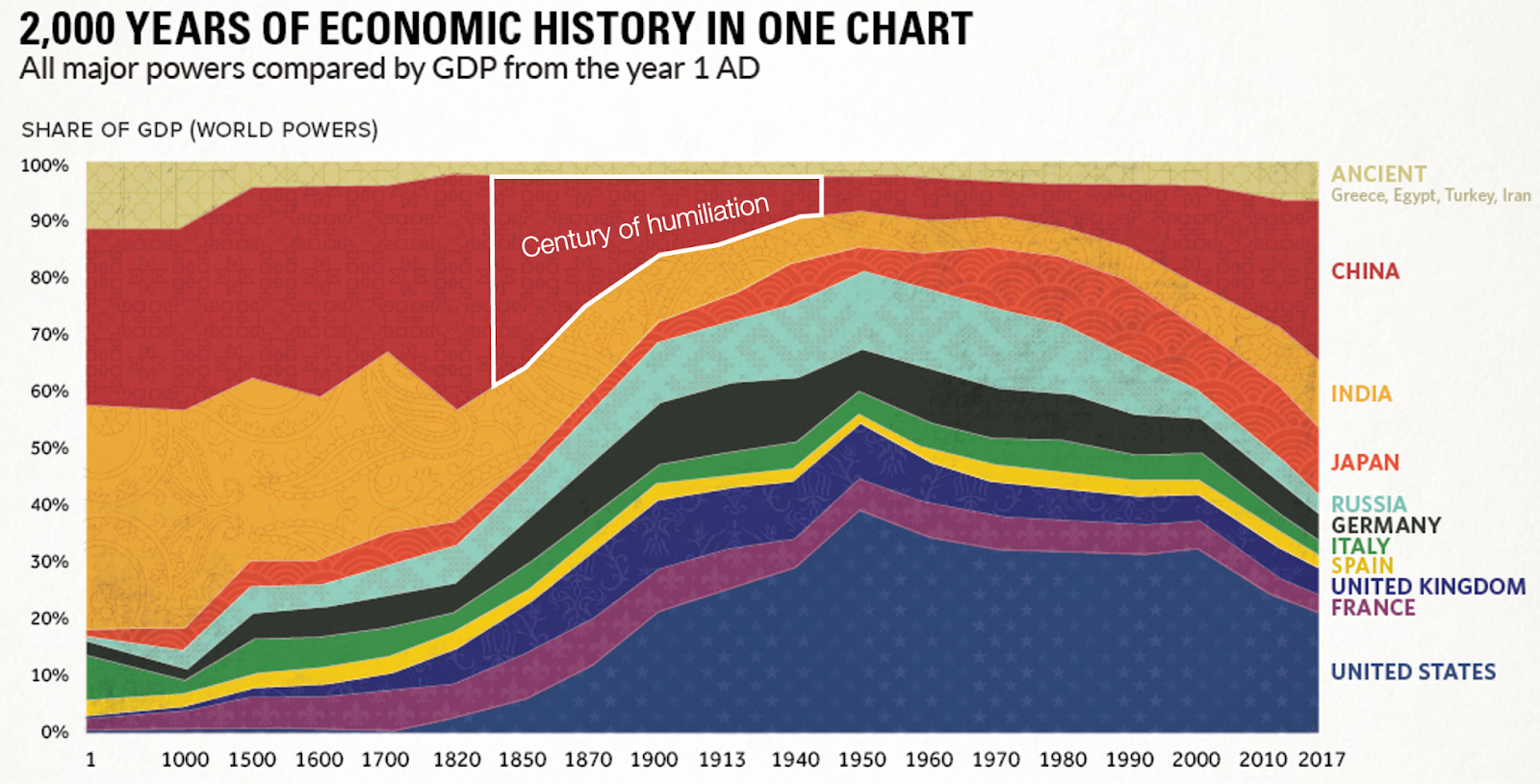

This is what the Chinese call the century of humiliation, when China went from the richest and most advanced nation of the world to a dirt poor backwater.11

China Today

This has many repercussions to this day. This century of humiliation is a core reason why China is so assertive about its growth and expansion today. It believes it should just get back its rightful place in the world, which was stolen by Western powers by force and subjugated through drug addiction. The Chinese CCP takes its legitimacy from ending this dark period of Chinese history. This is why it’s so sensitive to US power, why it builds up its military now, why education is so patriotic, why it wants to close that chapter by unifying with Taiwan.12

What can we expect from China based on this? To continue this buildup, to become stronger and more nationalistic, to never ask for other great powers’ help, to continue getting land buffers around it, and to try hard to unify with Taiwan.

As for trade, today, we’re back to a world where China is a net exporter.

Once again, China produces more than it consumes, which means it’s more interested in foreign money than goods. Once again, Western governments freak out about this deficit, which can’t continue forever.

If we follow history, what can we expect to happen in the future? Like for silk, porcelain, and tea, Western countries will likely try to figure out Chinese manufacturing prowess and replicate it in the West—exactly what China has been doing to Western countries for the past 45 years.

China is protecting its economy from foreign trade like it has done for thousands of years. So if the Opium Wars are a valid precedent, Western countries will do whatever they can to open up trade to China. This is the context for the trade war that Trump has started, except this time Chinese markets can’t be opened up with guns. Or can they? Will this eventually lead to war?

I think there’s one fundamental difference between today and previous instances: currency. For 2,000 years, China was obsessed about hoarding one thing: silver. Why? Why was silver so important? Why did China need it so much? Why couldn’t it produce it? Why isn’t it as important today as it was in the past? Has US debt replaced silver? These are the questions I’m going to answer in this week’s premium article.

ChatGPT tells me a sestertius is worth $2-$30 today if you compare food and wages, so 100M sesterces would be about $200M-$3B today. It also estimates the Roman Empire’s budget at 800M sesterces, so the spend on luxury goods would be equivalent to ~12% of the annual budget of the government!

In most history texts you read, these lists of goods are named in passing, but in reality this is where most of the interesting stuff lies. For example, where did that amber come from? Most of it was from the Baltic shores, near what is today Gdansk, Poland. This in turn was one of the sources of income and development for that region, starting with the Romans. Amber is a product of that region to this day.

There are several reports of that time that mention the Chinese’s refusal to meet or interact during trades. I find that fascinating.

Some porcelain arrived earlier than that, in the 1300s or so, via Constantinople, but the volume was extremely low at that time.

Mainly Potosí in Bolivia and Zacatecas in Mexico

Fun fact: part of this success that was unique to Britain was the hand of the government. From Wikipedia: “The British East India Company, at the time, had a greater interest in the tea trade than in the coffee trade, as competition for coffee had heightened internationally with the expansion of coffeehouses throughout the rest of Europe. Government policy fostered trade with India and China, and the government offered encouragements to anything that would stimulate demand for tea. Tea had become fashionable at court, and tea houses, which drew their clientele from both sexes, began to grow in popularity. The growing popularity of tea is explained by the ease with which it is prepared. ‘To brew tea, all that is needed is to add boiling water; coffee, in contrast, required roasting, grinding and brewing.’"

The letter is so arrogant, it’s really entertaining. It goes on, addressing why the British can’t take land for trade purposes, can’t trade with more ports, and can’t spread Christianism. I’m especially a fan of this sentence: “It may be, O King, that the above proposals have been wantonly made by your Ambassador on his own responsibility, or peradventure you yourself are ignorant of our dynastic regulations and had no intention of transgressing them when you expressed these wild ideas and hopes....”

And what are today India, Sri Lanka, Bangladesh, Pakistan, and parts of Afghanistan.

Opium was already known and used in China, just not widespread. The British spread its smoking, which made it more successful.

Originally just Britain and France, who fought the Chinese in the 2nd Opium War. The US and Russia would also get access to trade in China, and later other countries like the Netherlands, Portugal, Italy, Japan…

In terms of GDP per capita for sure. With 500M people in 1950, that was hardly a backwater in terms of overall GDP or power.

Or why Singapore is so aggressive against drugs today: It was founded by a Chinese majority, and the memory of the opium tragedy is still fresh.

The chart with 2,000 years of economic history looks much more compelling when the x-axis shows the 2,000 years on the same scale. It could even show 1 or 2 thousand years more.

The core message of this charts is not the "century of humiliation," but that India and China ruled the world economy for thousands of years. No one else ever came close. And the current situation, which we see as the natural order of things, is not as natural as we in the West think.

A fact that 99% of people here in the "developed world" are ignorant of.

Just 40 years ago, it was still common in rural area in Southern France to tend for silkworms. Teens could get some spare money from it; I know a guy who bought his first moped with silk money.