How to Become the Best in the World at Something

With skill stacking, you don’t need to be at the top to be extraordinary

This article is dedicated to all the people who ever dreamed of achieving something

special.

How hard is it to become an NBA player? Most of them have been honing their skills on the basketball court practically since infancy: years of countless practices, camps, and games to improve their shooting, ball-handling, passing, defense...

As you can imagine, the success rate for becoming an NBA player is remarkably low. There are 30 teams of about 15 players each, for a total of roughly 450—not a ton of people, especially given that over 500,000 young men play youth basketball in the US.

Fewer than one in a thousand will make it to the pros.

So let’s be realistic.

You aren’t going to make it to the NBA.

You will not become the president of the United States.

You will not be the world’s greatest writer, nor the top chess player, nor the most masterful public speaker.

You will never be the best in the world at any given skill.

There will always be someone working harder.

There will always be someone with greater genetic gifts, or more luck, or both.

Put in another way, the more you progress on any given skill, the harder it is to stand out further.

So trying to be the best at one thing isn’t the smartest path to success. Instead, you should put your effort into mastering a combination of skills. The solution is skill stacking, a concept popularized by Scott Adams. Here’s how it works.

The Basics

Years ago, a friend of mine was about to take the GMAT1. He was hoping to get into some of the top grad schools, and nailing this test was a key step in the process. His first-choice school, Stanford, would only accept the top 6% of applicants. That meant he needed to score in the 94th percentile to have a shot at getting in.

The day of the test, he was trembling. He sat in front of his computer in the test room, looking at the clock. One minute left to start. Twenty seconds. One. Begin.

After four intense hours, he finished the test. As he sighed in relief, a red alert started blinking furiously on the screen. YOUR RESULTS ARE IN.

He scored in the 90th percentile on the math portion, and in the 95th percentile on the verbal portion. Does that mean I’m in the 92nd percentile?! Oh nooo! He was dismayed. His heart sank. Those scores wouldn’t cut it. Goodbye, Stanford.

But then he looked closer. He saw something else: His overall score was in the 98th percentile. What?! How was this possible?

Most math-minded test-takers are bad with words, and the word-loving ones can’t quite hack the fractions. So while my friend’s score wasn’t the best in any one section, it was among the best when these sections were considered in combination.

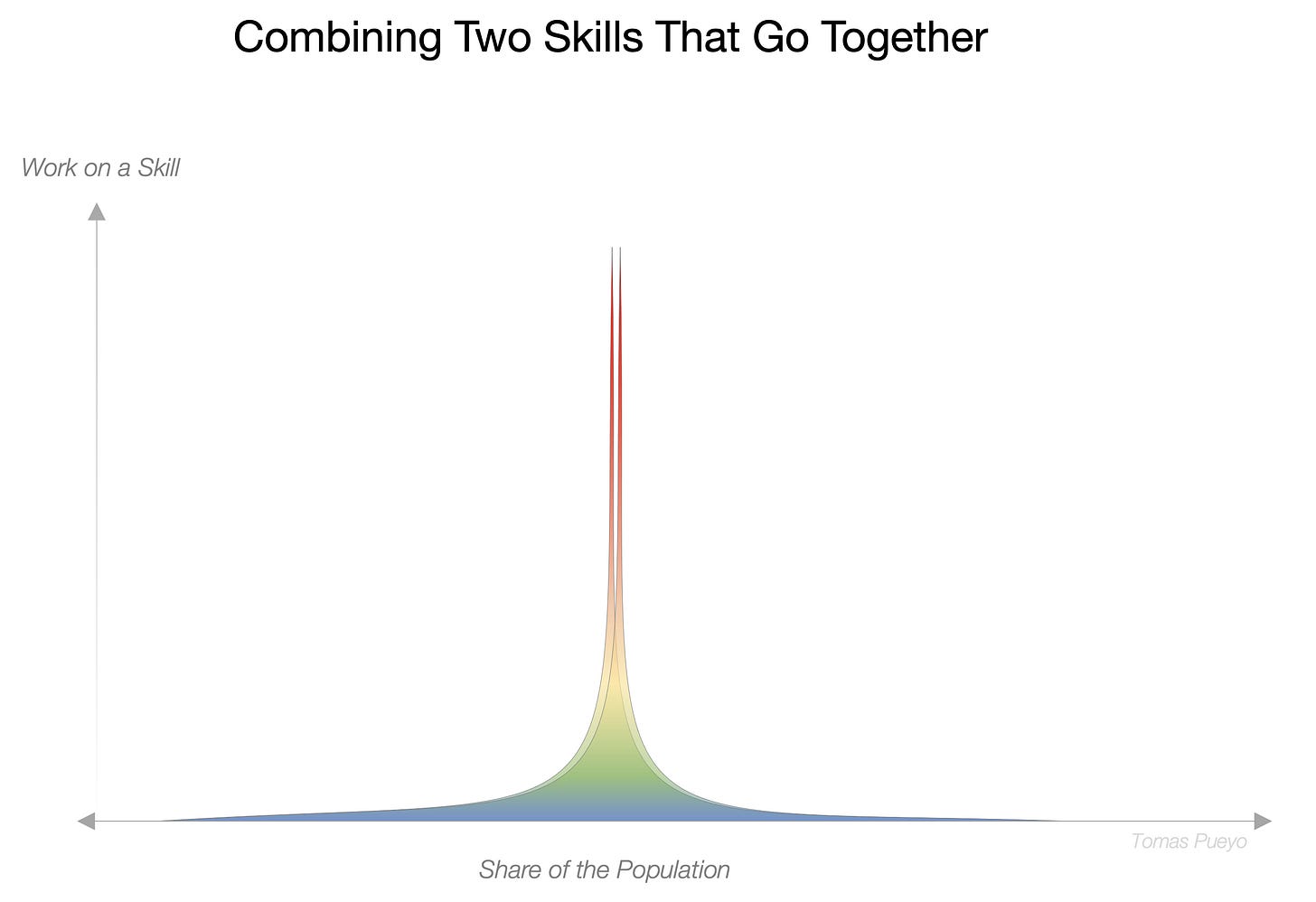

This is how skill stacking works. It’s easier and more effective to be in the top 10% in several different skills—your “stack”—than it is to be in the top 1% in any one skill. Take a look at this chart.

Let’s run some numbers on this. If your city has a million people, for example, and you belong to the top 10% of six skills, that’s 1,000,000 x 10% x 10% x 10% x 10% x 10% x 10% = 1. You’re the number one person in your city with those six skills. Bump that number up to 10 skills? Boom, you’re the best in the world at that combination of 10 skills.

Ideally, the skills wouldn’t just be unique, but also complementary. Imagine someone who is reasonably good at public speaking, fundraising, speech-writing, charisma, networking, social media, and persuasion. Who is this person? A successful politician. The most successful politicians don’t seem to be off-the-charts amazing at individual skills, do they? But they check off the right boxes that allow them to thrive.

This principle applies across all fields. A writer can be just about the best prose stylist there is, but probably won’t find as much success as the person who is a reasonably good prose stylist, a strong self-promoter, a pretty fast writer, an engaging public speaker, and has the interpersonal skills to connect with important people in the publishing industry.

Skill Stackers in Action

Self-help guru Gary Vaynerchuk is a great example of a skill stacker.

He has 9 million Instagram followers, 2.5 million Twitter followers, over 3 million YouTube subscribers, and an active blog that people read as if it were holy scripture. On these channels, you’ll find content that is solid but not exactly mind-blowing. The magic that sets Vaynerchuk apart is his skill stack: The fact that he’s not just a good writer but is also savvy on social media and business, good at public speaking, and great at personal branding is what makes him one of the top self-help gurus in his field.

The principle applies to Steve Jobs, too. At the heart of Jobs’ skill stack was a passion for design, be it fonts, packaging, or architecture. He was obsessive about the look and feel of his products. He was never the best in the world at design, but over time, he developed a keen understanding of winning design principles. He later combined his various design skills with deep insight about what people want, tech knowledge, a strategic mind, salesmanship, an ability to extract everything from his employees, and entrepreneurial skills. Together, these skills helped him form a company that was focused on advanced technology and beautiful design.

Like these, thousands are succeeding through their skill stack, like the musician who loved coding and ended making a living by creating apps for musicians, or Dinara Kasko, an architect who loved baking and ended up building an empire on top of architected desserts.

What Is Your Special Skill Stack?

How can you apply this to yourself?

In discovering your own skill stack, consider the combination of skills. You want them to be related in some way, but not too similar. For example, if you’re in the top 1% in journalism, also being in the top 1% in writing skills isn’t going to be a big differentiator. Most top journalists are good writers. What’s different about stacking is having skills that not only work together but also are varied enough to make you stand out.

The best skills to choose are those that don’t tend to go together, but complement each other well. For example, engineers aren’t known to be great public speakers, so those who are have a huge professional advantage. (This is what’s called “covariance” in statistics. The math about the number of skills above assumes skills are completely independent.)

My own path to skill stacking led me to give a TEDx Talk titled “Why Stories Captivate”.

When I was a child, my father, who worked in advertising, told me everything he knew about storytelling. I took that passion with me, reading about how to craft stories throughout my life. Later, as an engineering student, I wanted to understand how things are made. However, when reading about storytelling structure, I noticed experts just gave recipes on how to craft stories without explaining why. Thankfully, through my job designing online products, I learned a lot about psychology and experience design, which led me to connect the structure of stories with how our brains work. Finally, a decade ago, I started going to Toastmasters to learn about public speaking because I was so afraid of it.

I’m one of a bunch of people in the world with enough knowledge about storytelling, design, and psychology to make a connection between all three. But of those people, only a few have an engineering mindset to deconstruct the problem. And of the very few who can do that, only a tiny fraction are good enough at public speaking to convert the theories into a TEDx Talk.

Let’s collapse the vertical axis and look at it from above.

Even if I’m not in the yellow-red area in any of these skills, very few people overlap in all of them.

Something very similar happened in 2020, when my COVID articles exploded virally. I’ll cover that in the premium article this week, along with more details on how to pick the skills for your stack.

The Takeaway

Stop trying to be the best at one skill. You’re setting yourself up for some serious disappointment. Instead, ask yourself: In what niche do I want to stand out? What combination of skills do I need to be unique in that niche?

If anybody ever told you to stop following your passions, to stop being a “Jack of All Trade, Master of None”, tell them it’s “Jack of Some Trades, Master of One”.

It’s not about being great at any one thing — you just need to be pretty good at an array of useful skills that, when combined, make you truly one of a kind.

Thank you for reading my article today. It is deeply personal, as I, too, dreamed one day of something weird:

I dreamed that an engineer as charismatic as an asparagus like me could one day contribute back to the world through impactful communication. I spent the following decade on my communication skills. When my COVID articles passed 60 million readers in 2020, I was rewarded with more impact than I could ever dreamed of.

Sometimes, when we’re in a dark place, spending weeks on something others disdain, all we need is a little encouragement, a friendly little tap on the back, a voice who tells us: “You’re not that crazy. You’re allowed to dream your weird dreams.” If you, or someone like you, ever feel like they need that little nudge forward, send them this essay to tell them: “There’s more weirdos like us. Keep fighting.”

I published the first version of this article right before the pandemic. It got nearly 300,000 views.

I stacked skills to write articles like this one and the COVID pieces. In this week’s premium article, I’ll go over the skill stack I developed and how I did it.

I will also answer all the questions I’ve gotten since, such as what types of skills you should you pick to become the best in the world at something. I’ll also cover how to develop these skills efficiently, how to think about skill covariance, when to follow the advice “follow your passion”, where the same concept of skill stacking appears in other areas, what other benefits there are from skill stacking, and the importance of Epistemic Trespassing. Subscribe to read it!

Translation available in Arabic.

It’s a reasoning test that most business schools ask you to take to consider broadly your intelligence and/or your willingness to work very very hard to ace it.

Another very insightful piece, Tomás; thank you. It is going straight to my 14 year old daughter who, in her first high school year, is currently struggling with a lot of these issues.

I am surprised you did not mention languages, though. I know you speak three, at least. Being fluent in several languages gives you not only more possibilities of communicating, but also a deeper understanding of how different people think, and how their thinking differs, and thus of adapting your messages to different publics.

Knowing different languages is closely related to understanding cultures. If the US lost the war in Afghanistan (as did previously the USSR, and the UK), it is mostly because they were not "culture literate," to say it some way, in Afghan culture. Being able to understand and adapt to different cultures is a skill that can be paired to amplify any other you might have.

Secondly, as a woman, while reading your piece, I kept thinking: "In a way, he is talking about what we know as 'multitasking'." Women are excellent at being good in different domains, because we are always multitasking. From cooking (which is chemistry and physics), to psychology (children), to running a home (management). I suspect many women have known this all along. You just have presented it in an academic format (I guess these are your storytelling skills at work).

It is said that Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz (a Mexican nun, and a genius of the 17th century) once remarked: "If Aristotle had known how to cook, he would have discovered many more things than he did."

So yes, having different 'niches' definitively takes you to the next level. Wanting to be No. 1 carries a lot of frustration. Wanting to be better every day is probably more rewarding.

Your post today resonates deeply, for me, with something I've been thinking about for many years. There's a famous essay by Isaiah Berlin, "The Hedgehog and the Fox", whose point is that one of the most profound differences that divide human beings is between foxes and hedgehogs. It all starts with an obscure fragment by a Greek poet, Archilochus: "The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing". The poet seems sympathetic with the hedgehog: imagine a fox meaning to kill and eat a hedgehog. She tries many different strategies, but every time the hedgehog rolls up in a ball of spikes, and the fox is frustrated.

Berlin doesn't take sides but classifies writers and thinkers according to this criterion. By instinct, I take sides with the foxes. I think I am a fox myself. Maybe not a very clever one, but a fox nevertheless.

It seems to me that from your angle, foxes have a significant advantage over hedgehogs. What's your opinion?

For completeness, below you find a lengthy quotation from Berlin's essay:

"There is a line among the fragments of the Greek poet Archilochus which says: ‘The fox knows many things, but the hedgehog knows one big thing.’ Scholars have differed about the correct interpretation of these dark words, which may mean no more than that the fox, for all his cunning, is defeated by the hedgehog’s one defence. But, taken figuratively, the words can be made to yield a sense in which they mark one of the deepest differences which divide writers and thinkers, and, it may be, human beings in general. For there exists a great chasm between those, on one side, who relate everything to a single central vision, one system, less or more coherent or articulate, in terms of which they understand, think and feel – a single, universal, organising principle in terms of which alone all that they are and say has significance – and, on the other side, those who pursue many ends, often unrelated and even contradictory, connected, if at all, only in some de facto way, for some psychological or physiological cause, related to no moral or aesthetic principle. These last lead lives, perform acts and entertain ideas that are centrifugal rather than centripetal; their thought is scattered or diffused, moving on many levels, seizing upon the essence of a vast variety of experiences and objects for what they are in themselves, without, consciously or unconsciously, seeking to fit them into, or exclude them from, any one unchanging, all-embracing, sometimes self-contradictory and incomplete, at times fanatical, unitary inner vision. The first kind of intellectual and artistic personality belongs to the hedgehogs, the second to the foxes; and without insisting on a rigid classification, we may, without too much fear of contradiction, say that, in this sense, Dante belongs to the first category, Shakespeare to the second; Plato, Lucretius, Pascal, Hegel, Dostoevsky, Nietzsche, Ibsen, Proust are, in varying degrees, hedgehogs; Herodotus, Aristotle, Montaigne, Erasmus, Molière, Goethe, Pushkin, Balzac, Joyce are foxes.

Of course, like all over-simple classifications of this type, the dichotomy becomes, if pressed, artificial, scholastic and ultimately absurd. But if it is not an aid to serious criticism, neither should it be rejected as being merely superficial or frivolous: like all distinctions which embody any degree of truth, it offers a point of view from which to look and compare, a starting-point for genuine investigation."

Isaiah Berlin. The Hedgehog and the Fox: An Essay on Tolstoy's View of History. Princeton University Press.