Mexico Before Europeans

(and before the Aztecs)

Last week, I took my first week off this year. As a reminder, I take four weeks off per year. Usually, it’s hard for me to predict beforehand when I’ll take these weeks off. I suspect I’ll take another one in August.

This week, I’m looking at the long-term past of Mexico. And aside from the consistent and incredibly useful support of your editors Shoni and Heidi, today I also wanted to thank MajoraZ for their amazing support editing, correcting, and adding to this article. Go look at their content if you want to know more about Mesoamerican history!

What I thought I knew about Mesoamerica when the Spaniards arrived was mostly wrong.

Hernán Cortés didn’t conquer Tenochtitlan with a handful of Spanish soldiers, but rather with a bigger army and the help of alliances with indigenous city-states.

Indeed, local politics were a major reason why the Spaniards took control of the region, to the point where it's unclear who played whom the most between the Conquistadors and Mesoamerican kings and officials.

Some agreements that the Spanish made with the indigenous people still apply to this day.

It was reasonable for the Aztec Emperor Moctezuma II to invite the Spaniards into Tenochtitlan.

The Aztec were originally puny, but their rise was meteoric.

Before and at the same time as the Aztec and Maya, there were dozens of other similarly accomplished civilizations and kingdoms, all of whom were connected to each other via trade and diplomacy.

I thought the Maya had mostly disappeared by the time of the Aztec and the arrival of the Spanish, but they were still around then and even are today.

The word “Aztec” is contentious.

There’s an important difference between Mexica and Aztec.

Tenochtitlan was not built on a lake because it was great, but because it was a backwater.

The history of the region gives us many clues about how the ancients viewed inequality.

As we learn about these things, we’re also going to learn some amazing facts, like why cenotes and caves form in Yucatan, why the magnificent city of Teotihuacan had toilets and why it disappeared, and much more.

I find the easiest way to understand all of this is to go back to the root: What is the history of the region, and why were the Aztecs the way they were when the Spaniards arrived? So this week, we’re starting with this premium article on Mesoamerican history before Columbus.

1. The Rise of Agriculture

Cacao, maize, beans, tomato, avocado, vanilla, squash and chili were all domesticated in Mesoamerica starting around 7000 BC. They also kept turkeys, dogs, and peccaries, most likely for companionship and ceremonial purposes as well as food.1

Why does this matter? Because their cultivation is what allowed local civilizations to flourish. Without these crops, no civilization would have been possible there.

2. The First Civilization Was Between the Territories of the Aztecs and the Mayas

Remains of agriculture appear across the region, showing that these crops circulated throughout. But the first place where they created some sort of civilization is here:

The Olmecs were the true OG. There had been some proto-cultures around 2500 BC, but by 1200 BC, the Olmecs had truly emerged. To give you a sense of how ancient this was, the Egyptians, the Babylonians, the early Chinese, and the very early Greeks (Mycenaeans) lived at the same time. Super early!

Notice how this is just at the fall line of the mountains there, and always close to some rivers:

There were groups of villages and towns, and usually one predominant city in the region with a few thousand inhabitants, like San Lorenzo.2

San Lorenzo is famous for these big fat heads:

It’s unclear if these were fully-formed states, but we can see higher levels of organization emerging. For example, archaeologists think that San Lorenzo had rulers that had altars they used as thrones, and these big heads were the same altars, recarved after death to represent the rulers!

Here’s something surprising: The city didn’t have walls or other defenses, so the goal of these cities was not mainly one of protection. Then what was it? Just markets? Administration?

A clue comes from its heads, its altars, its palaces, underground drains, water channels… The public works were so extensive that locals moved an insane amount of dirt:

The core of San Lorenzo covers 55 hectares (140 acres) that were further modified through extensive filling and leveling. By one estimate 500,000 to 2,000,000 cubic metres (18,000,000 to 71,000,000 cu ft) of earthen fill were needed, moved by the basketload.

It would have taken tens of millions of trips to make it happen!

People left for La Venta, either because of war, uprising, or more likely some geographic changes like the riverbed moving. This foreshadowed later events, as around 400-350 BC, the Olmec population dropped precipitously and there would be little population in the area until the 19th century! The cause is unknown, but geography is the main suspect—maybe tectonic shifts or heavy volcanic activity. After these changes, it might well be that people just left for another, better land.

One thing that’s interesting to realize is that Olmec items appear across the region, from CDMX to Guatemala, which proves two things:

The Olmecs were not the only emerging civilization in Mesoamerica.

These civilizations were interconnected.

Soon after the Olmecs emerged, other civilizations started appearing everywhere in the region, probably because the elites of other developing civilizations adopted Olmec styles.

Here you can see some sites where Olmec stylistic influence has been recorded, including the Texcoco lake where the Aztecs eventually appeared (the lake is where you see Tlatilco and Tlapacoya on the map).

Soon, Cuicuilco emerged on the lakeshore, with its famous cylindrical pyramid, built around 800-600 BC.

The city was bigger than the Olmec centers—20,000 people. It also had defensive walls, which means that unlike cities in the Olmec region, it had to defend itself against its neighbors.

It was built around pools and streams, and crucially, at the feet of the Xitle volcano, which erupted around 300 BC and destroyed the city.

This is around the time that Teotihuacan emerged (not to be confused with Tenochtitlan).

3. Teotihuacan

Teotihuacan is among the most visited archeological sites in all of the American Continent.

It’s on the opposite side of Lake Texcoco from Cuicuilco:

In fact, Teotihuacan became the dominant center in the Lake Texcoco basin—the Valley of Mexico—due to eruptions displacing people from Cuicuilco and other sites, who then migrated into Teotihuacan. At its height between AD 200-500, it had ~100,000 denizens, around the 6th largest in the world.

But Teotihuacan grew so large because it attracted immigration from all around Mesoamerica, not just the Valley of Mexico. We know this for many reasons, one of which is that it had ethnic neighborhoods! There was a Mayan neighborhood, a Zapotec one, and many others, the way we have Chinatowns in Western cities today.

It was the first city in the Americas to be planned as a grid, and even after its heyday, this was rare in Mesoamerica.

This grid layout was so important that the locals even changed the course of rivers through the grid, some aligned to appear to erupt out of specific structures.

Teotihuacan is famous for its pyramids.

Another crazy fact about the city is that a huge part of the population lived in well-built multi-family apartment compounds.

I didn’t realize how rich the city was until I dug into it. Many houses had lavishly-decorated walls.

And some even had toilets!

Unfortunately, at the same time the Roman Empire was decaying, so was Teotihuacan—possibly for some of the same reasons: crop failures due to volcanic eruptions between AD 536 and 560.

The decay of Teotihuacan was interesting. It used to have superb monuments and sumptuous palaces along its main thoroughfare, the Avenue of the Dead. But most of its monuments and the buildings of the ruling class were sacked and systematically burned around 600 AC. There is now a complete lack of symbols of power. Other buildings were left intact. What might have happened?

Maybe an invading force killed and replaced the ruling class? But Teotihuacan was like the Olmec civilization—and many other cities in Mesoamerica: It had no defenses and no military buildings, indicating no outside threats. No traces of foreign invasion can be found. What then?

According to David Graeber in The Dawn of Everything, this was due to an uprising that eliminated the inequalities forced down by the elites and ushered in a much more egalitarian period in Teotihuacan history, which lasted until the 700s as it continued decaying.

After the fall of Teotihuacan, no city in the Texcoco Lake area predominated for centuries. Cultures like Toltecs and Chichimecas influenced the area, but none prevailed… until the Aztecs emerged.

But before we talk about them, let’s have a look at the other civilizations in Mesoamerica at the time.

4. The Maya

Most people know the Maya for the period between AD 200 and AD 900,3 and think it then collapsed. However, the Maya had existed for centuries before that… And they were still around when the Spaniards arrived! Even today, there are millions of Maya people. Why did their civilization develop the way it did, and why did the Classic Collapse occur?

The Mayan culture is world famous, for its stelae:

For its paintings:

And for its pyramids:

Pyramids again! They are everywhere, which makes sense since all these peoples were trading and interacting with each other.

There are tens of thousands of Maya sites, some of which are being discovered to this day thanks to novel methods. Aguada Fenix, for example, discovered with laser tech, shows how the Maya developed complex sites earlier than previously thought—maybe during the heyday of Olmec sites like San Lorenzo and La Venta!

We have a good understanding of the Maya because they recorded a lot of what they did, mostly through their architecture and inscriptions in stelae, but also through books.

Here’s something to make your blood boil: The Church burned thousands of Mesoamerican books like this one. As someone4 said, the Church’s book-burning in Mesoamerica is the reason we talk about the region in archaeology classes and not history classes.

Going back to the Maya, if you remember from a previous article, I mentioned that there are no rivers in the Yucatan Peninsula, so they had to be very inventive to gather water. Here you can see how the city of Tikal was structured to gather water into a reservoir.5

Indeed, Tikal was impressive:

However, Maya and most other Mesoamerican cities were less dense than Teotihuacan, with smaller urban cores and spaced out suburbs.6

The largest Maya cities like Tikal and Calakmul only matched Teotihuacan’s population when including their extended sprawl of suburbs and the nearby sites they connected. Indeed, the bigger cities confronted each other by forming coalitions with smaller cities, like Tikal vs Calakmul:

How do we know these cities were less dense, and so connected to central Mexico? Through archaeology, records of trade, and inscriptions. For example, there were political marriages across long distances, and even wars. For example, there is even evidence that Teotihuacan, 1200km away, invaded Maya cities and replaced local rulers around AD 400!

Why was Maya civilization like this? Why did it have hundreds of smallish cities that rose and fell, instead of one strong city that could dominate? I haven’t found a clear-cut answer, but from what I can gather, it comes down to geography.

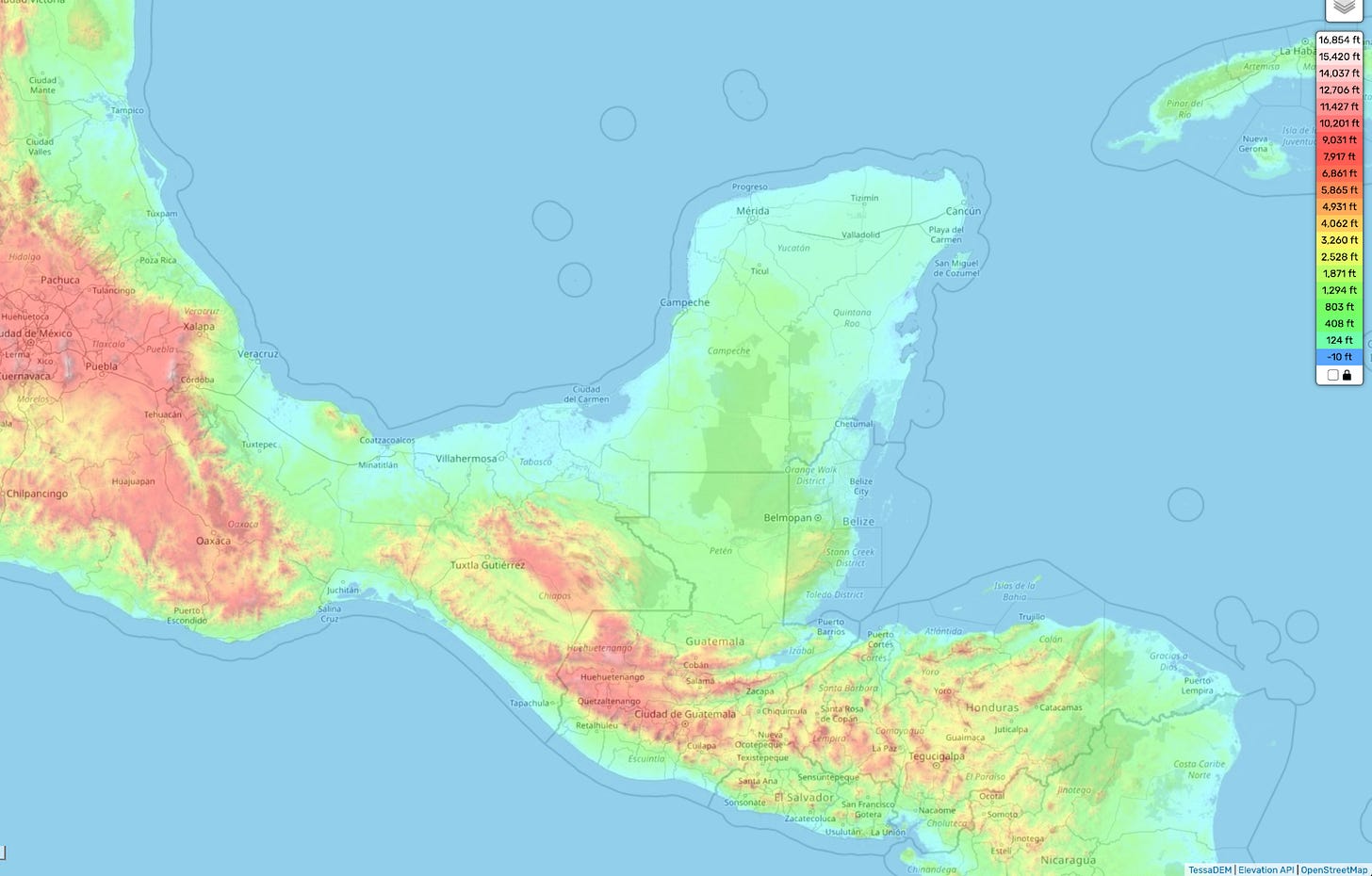

The Geography of the Yucatan

As I mentioned, the Yucatan Peninsula is flat and has no rivers. This means that every waterhole could sprout a town. There’s no river to control, nor a huge advantage in controlling it.

No river and thick jungle also means massive limits to mobility, which make it difficult to control vast swaths of territory. This was made worse by a lack of draft animals to help carry supplies and transport people. (Even in Central Mexico, without jungles, this plus the mountainous terrain limited long distance administration)

No mountains also means little mining, so fewer materials available to develop civilization, less trade, and less concentrated resources to fuel the emergence of a prevailing state.

Few rivers also means no alluvial plains fertilized with sediments, so land could be exhausted of its nutrients, and local cities would disappear.

It’s also easier for flatter lands to change substantially with climate change events. Maybe the volcanoes that cooled the world in the 500s AD also affected the Maya. Maybe other local climate events did the same, like with the Olmecs before them.

This begs the question of why the Yucatan is so flat and full of holes? Because it used to be seabed!

You can see today that it’s not just the land that is flat. It’s also the seabed:

For tens of millions of years, marine animals died and accumulated at the bottom of the sea, creating huge flat layers of shells that eventually became limestone. Except limestone dilutes more easily in water than other types of soil—especially if the water is somewhat acidic.

As the Yucatan Peninsula rose above the sea, it remained flat and covered in layers of limestone when rain started hitting it. But rain captures CO2 in the atmosphere, which increases its acidity. Acid dilutes limestone and creates holes in the ground.

This is what causes the cenotes and the underwater caves that I discussed in a previous article. These were important sources of freshwater and sacred sites to the Maya, viewed as underworld portals.

Since the Yucatan is so flat, water can’t easily flow into rivers, so instead it forms lakes. Their size depends on the balance between rain and the (very intense) heat that evaporates it.

This flat land also provides no defense against hurricanes. And hurricanes are common here!

I speculate that constant hurricanes don’t help civilization building, or for cities to remain at the same spot for millennia.

So all these reasons that might have caused a decentralized Maya civilization might also have caused its demise. It’s unclear why it started disintegrating around AD 800—, though it was likely a combination of warfare, environmental changes and droughts.

However, this was not the end of Maya civilization: the Classic Collapse mostly impacted the large sites in the Southern and Central Maya regions. Many smaller sites as well as larger cities to the North survived, or even grew! The famous site of Chichen Itza was populated into the 1200s, and the League of Mayapan, perhaps the largest Maya political network ever, nearly survived to Spanish contact.

When the Spainards arrived, there were still many towns and some cities. In fact, the last Maya city-state did not fall until 1697—after the Salem Witch Trials in colonial America!

Today, there are ~8 million Maya people, many of whom still speak Maya language and retain some traditional practices.

5. Zapotec

Here’s another civilization I knew nothing about.

The same way as the Aztecs were centered around the Mexico Valley, the Zapotecs were centered around the Oaxaca Valley.

You’ll notice this valley has a Y shape. Each of the arms hosted a different society, and they competed with each other. Eventually, a city emerged perched on a hill in the middle of the valley—Monte Alban.

Monte Alban was one of the first major cities to come to power in Mesoamerica, and may have even become Mesoamerica’s first formal bureaucratic state society. The hill it was located on provided it with a defensive location, and the city held many lavish tombs, but it suffered a decline around 600-700AC, around the time of Teotihuacan’s decline and the Classic Maya Collapse.

As with the Mayas, many Zapotec people still exist today!7

6. Toltecs

The Toltecs are perhaps the most debated subject in Mesoamerican history and archeology: They are described by the Aztecs as creators of high culture and a utopian civilization from ~AD 700-1100, but experts don’t know whether they actually existed or they were mythical!

The Toltec allegedly ruled from their city of Tollan, which might have been Teotihuacan, Cholula, or more probably on the site of Tula.

Tula was indeed a sizable city in Central Mexico after the fall of Teotihuacan but before the rise of the Aztec, and similarities between it and the Maya site of Chichen Itza seemingly bolstered the idea of Aztec and Maya accounts of a wide Toltec Empire.

So if the Toltecs were smaller, and might not even have existed, why do I mention them? Because:

Toltecs were based in yet another place in Mesoamerica, showing how many of these valleys and geographical regions hosted different civilizations

They show how connected all these different cultures were

The Aztecs considered themselves to be the offspring of the Toltecs

Takeaways

Civilizations have emerged and developed in Mexico in a similar fashion as in Eurasia. They just started somewhat later and developed more slowly, which makes sense given Jared Diamond’s hypothesis that Eurasia had many more lands and peoples to mix, compete, and share technologies, which made it evolve faster.

But that doesn’t mean Central America only gave rise to the Aztecs and the Maya. There were nearly 3,000 years of civilizational development before the Spaniards arrived. Each ecological niche sprung a different civilization, and all of them were connected, influenced each other, and fought each other.

But the special conditions of Mexico also created an interesting situation: One where a new state could emerge in a matter of decades to become a massive power. It’s time to dive into the meteoric rise and fall of the Aztecs, in the next (premium) article.

Mayas ate mostly vegetables, but the meat they ate includes deer, turkey, iguana, dog, and peccary.

Wikipedia mentions about 5,000 for San Lorenzo, and up to 13,000 including the surroundings. A paper gives a median population of a bit under 8,000.Iit's not clear if that's in reference to just the core .4-.5 km2 plateau or the wider ~ 7 km2 settlement.

This apogee of the Maya civilization is referred to as the “Classic period”.

I believe it’s /u/snickeringshadow in Reddit, a professional archeologist in West Mexico.

The reservoirs were even connected via canals with switching mechanisms and had filtration systems!

Not shown in the above renderings.

And the group that replaced them, the Mixtec.

Great write up. Not the focus of your article but Mexico is also home to the Chicxulub impact site and the ring of cenotes. Humbling to walk in the footprint of an event that wiped out 75% of life on earth. So much more to the country than costal tourist destinations.

Teotihuacan's main avenue is extraordinarily vast and long. You could fit a dozen Roman Forums in it. Anyway, thanks. Superb, pithy and oddly moving piece.