Not Sustainable ➡️ Abundant

The solution to pollution is neither dilution nor reduction

The solution to pollution is dilution.

That’s what people thought in the mid 20th Century.

Then, we realized it wasn’t.

I grew up in a world where fish in the sea were being decimated.

Where forests were burning.

Where oil was extracted at breakneck speed.

Where CO2 accumulated dangerously in the atmosphere.

Where cropland invaded forests and drove animals to extinction.

Where rivers became sewers.

Where cities sank as we drank their water tables.

Where garbage became mountains we just hid with a skin of mud.

Where plastics colonized the oceans and then colonized our brains.

That’s when Gaia appeared.

Gaia

Gaia, we were told, was weak. She was delicate. She had finite resources that humans were depleting at an ever-accelerating pace. She was a unique and beautiful blue marble to protect from the dangerous actions of her parasitic host, which was spreading like an infection that had started gangrening her limbs and would eventually kill her.

If you have a world with finite resources, you want it to be sustainable. You need to protect these resources from depletion. You need to stop the disease, the gangrene. You need to halt humans’ propensity to keep growing and consuming.

That’s what sustainability is: Keep what is there.

It implies: Shrink your population, shrink your consumption.

The motto had changed.

The solution to pollution is reduction.

But then I started studying each one of these resources, and the role of humans in depleting them, and the more I learned, the more my intuition for the world changed.

The Dramatic Changes of the World

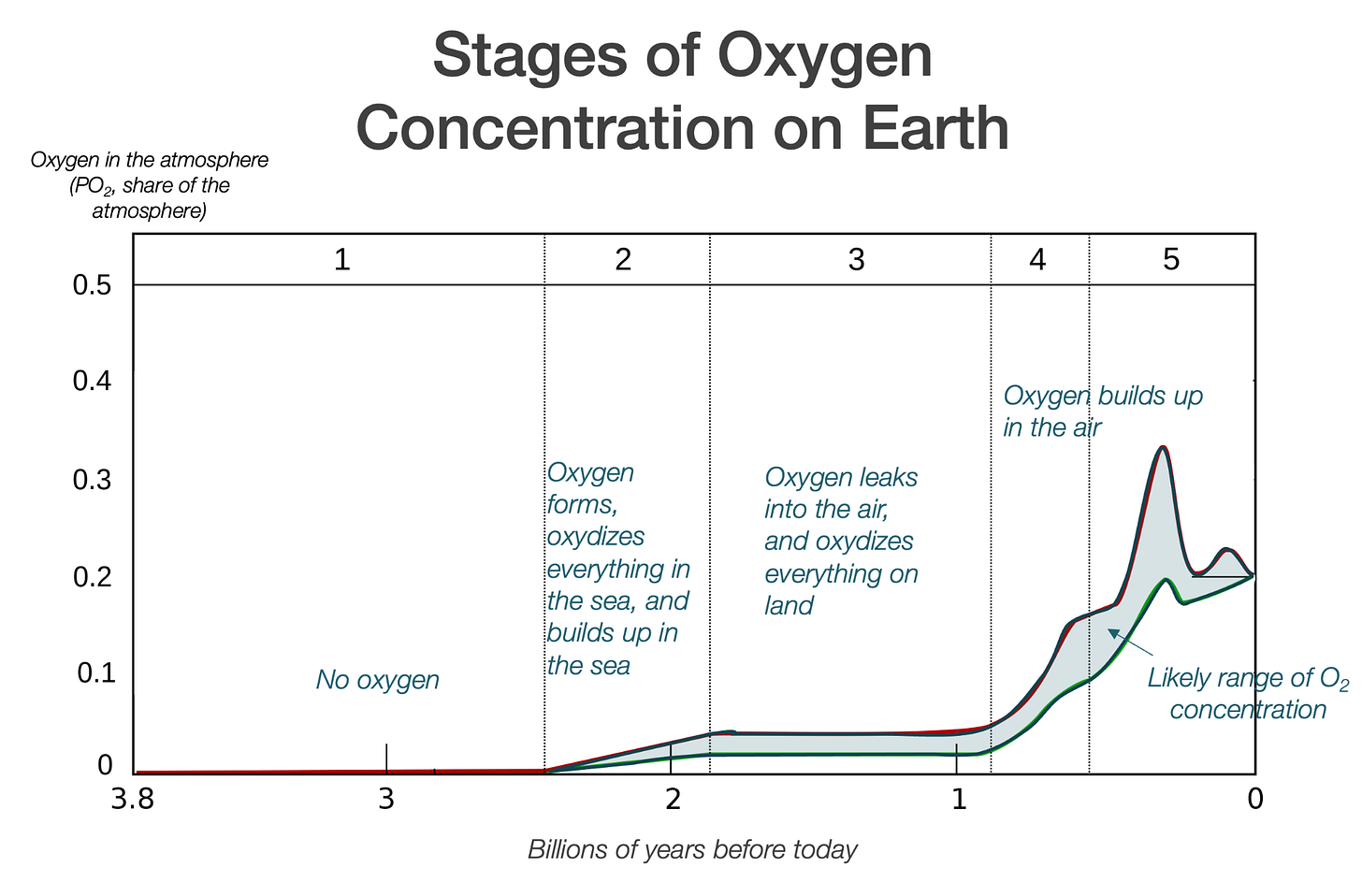

I discovered that, in the beginning, the atmosphere had no oxygen. Then, cyanobacteria and plants started releasing oxygen in a completely unsustainable way:

First, this oxygen oxidized the seas and the earth’s crust, literally changing the composition of everything we see today. Oxygen is a highly aggressive gas, and it attacks everything it touches. That red dirt everywhere on Earth? It wasn’t always red.

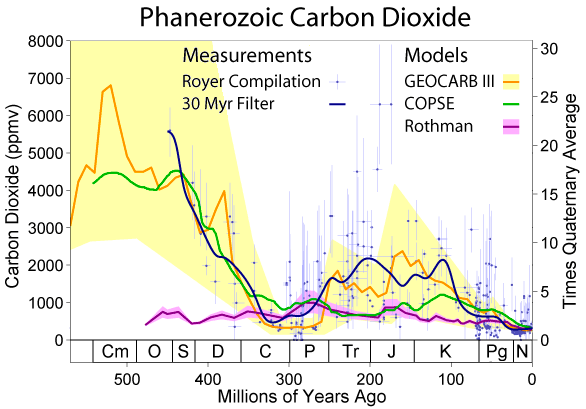

As oxygen accumulated, CO2 was catastrophically depleted.

Plants need CO2 to live, and yet 99% of it has been depleted from the atmosphere! How would we have reacted if we had seen this depletion happen during our existence? We would have panicked: CO2 is disappearing! We’re releasing too much of this toxic O2! This is all unsustainable!

Even things we consider immutable are changing all the time. When the Earth formed, days didn’t last 24h, they lasted 4 – 10h! This means a year may have had over 2,000 days! And that’s after the proto-Earth and Theia collided, forming the Earth and the Moon!

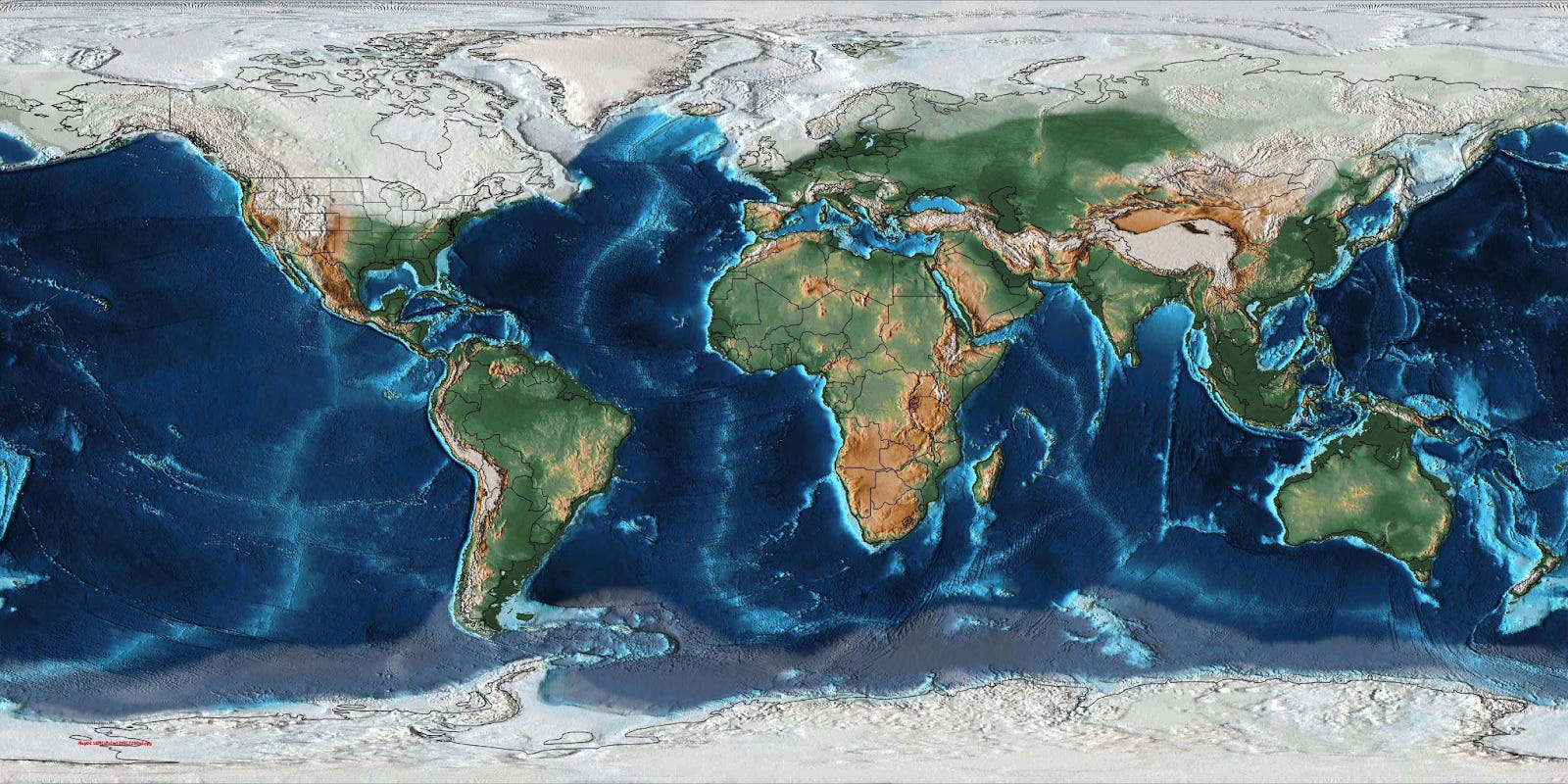

This was a world where continents were nothing like today.

And this is in just 150M years!

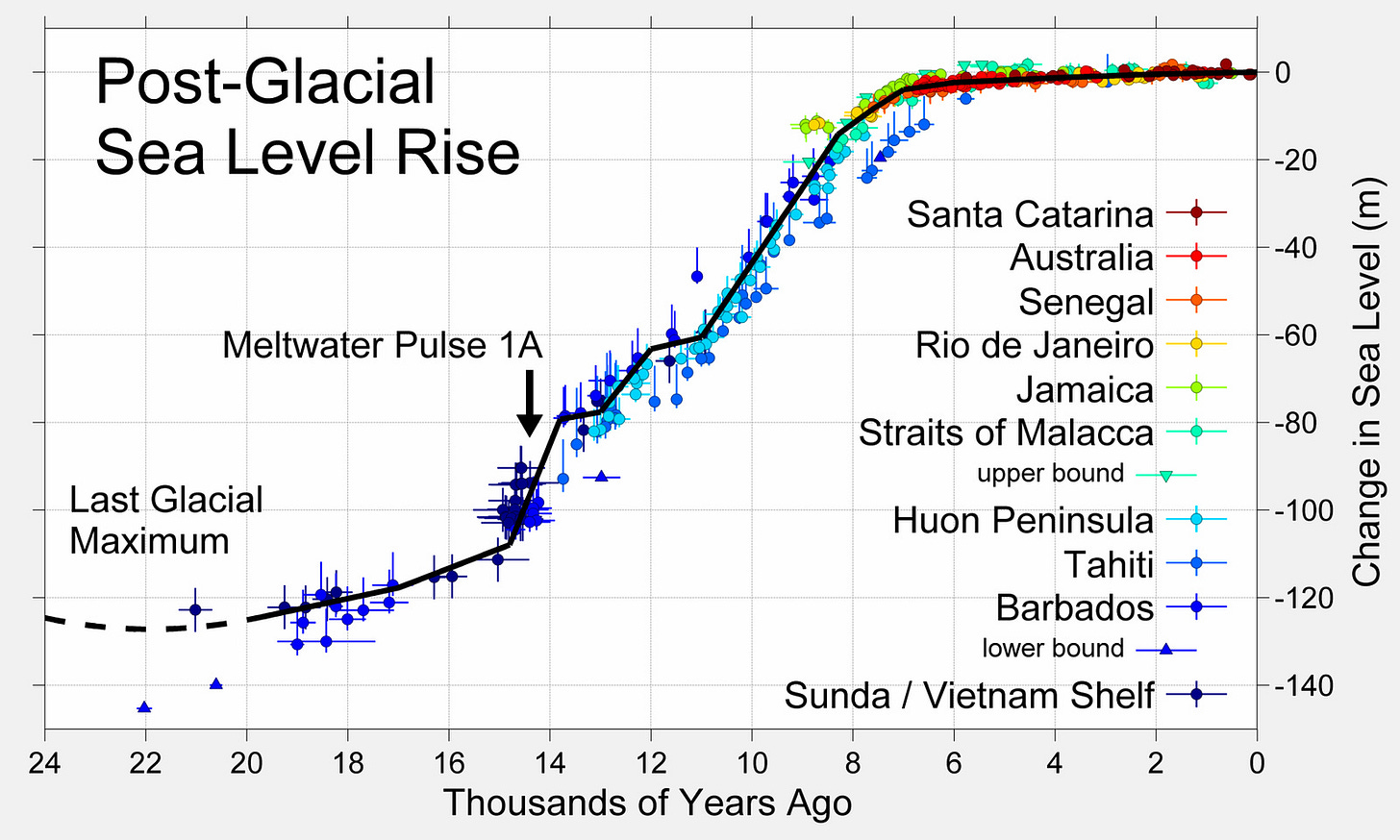

And yet these geological changes aren’t all ancient. Sea levels were 120 m lower just 20k years ago!

Of course, that’s because at the time, a huge chunk of the Earth was frozen.

But that’s not the most frozen the Earth might have ever been. That could have been during its Snowball Earth period, about 600M years ago.1

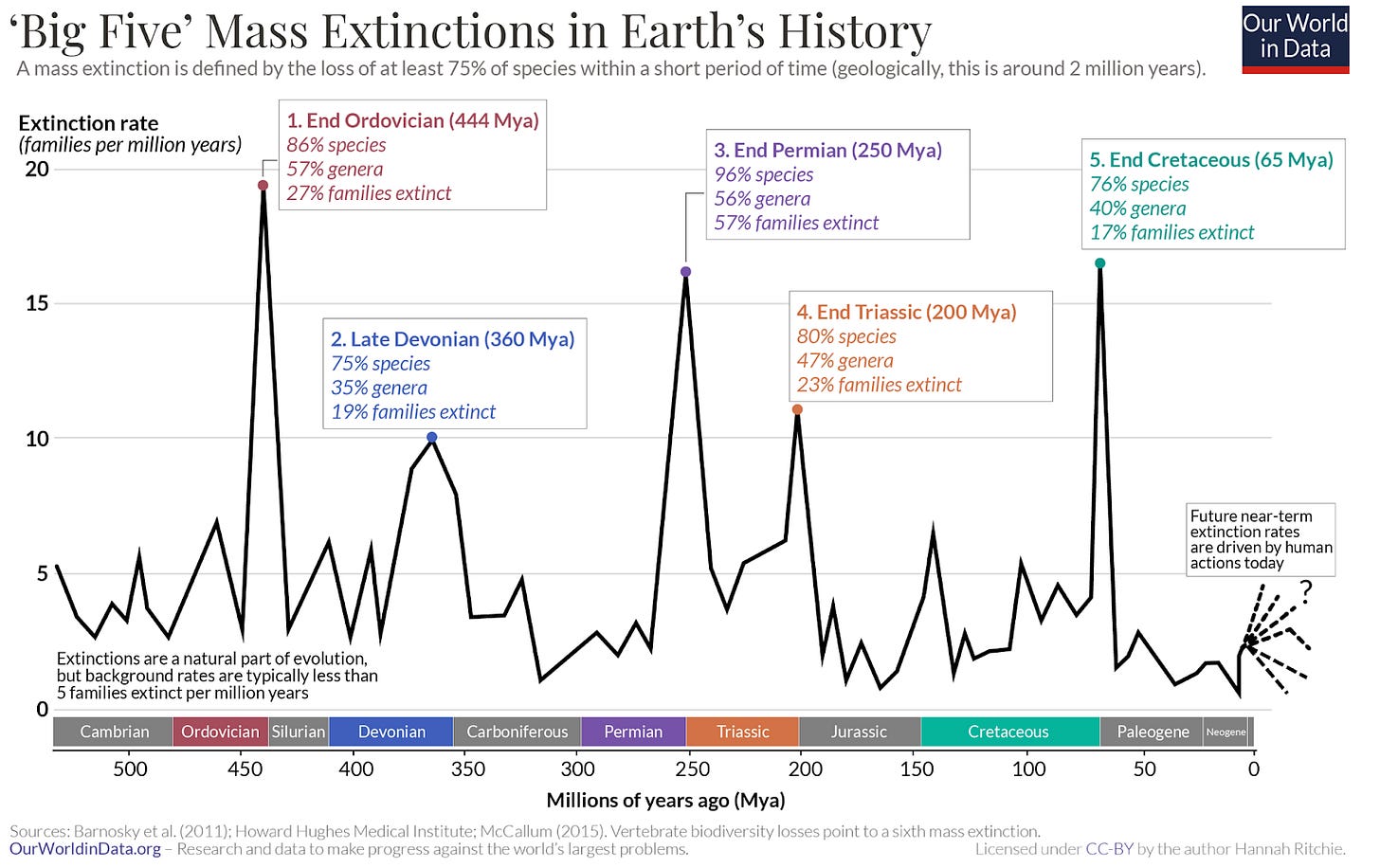

The Earth is a world where species have disappeared in five mass extinctions already, in an ongoing cycle of destruction and explosion.

Dinosaurs came and went.

There have been mammals bigger than the T-Rex.

But humans have driven huge mammals to extinction.

Humans have witnessed a green Sahara turn dry, oceans come and go, rivers shift, forests appear and disappear…

And yet, despite all these cataclysmic changes, despite these brutal forces that completely transformed the face of the Earth, here we all are, with our forests and our animals and our oxygen and our CO2 and our electromagnetic field. The Earth is not a delicate ecosystem; it is an engine, a mechanism with enough sunlight and heat and water and atmosphere for life and humans to thrive.

In this world, the most beautiful thing has emerged: intelligence. First, prokaryotes, followed by eukaryotes, and then vertebrates, and little by little, the complexity of life and intelligence exploded, reaching mammals, apes, and now humans. With humans, brains were good enough that they started improving intelligence faster than evolution. First through culture, then societies, books, media, the Internet, and now AI. Humans now shape sand to capture light and think, so that they become God.2

From Chaotic Cataclysms to Controlled Engineering

In our ignorance, we had no clue how to optimize nature. But with our capabilities, we now can. The world is a chaotic system we can improve.

This difference is crucial, because a delicate system must be preserved, while a complex mechanism can be optimized. A system that must be preserved is one that has a limited amount of resources. That’s what sustainability means: there’s only so much we have, so we should make sure we keep as much as we can untouched. There’s only so much we can use, we must make do with what we have.

But that’s not the reality. The reality is that there is so much on Earth that we can get substantially more from it than we have.

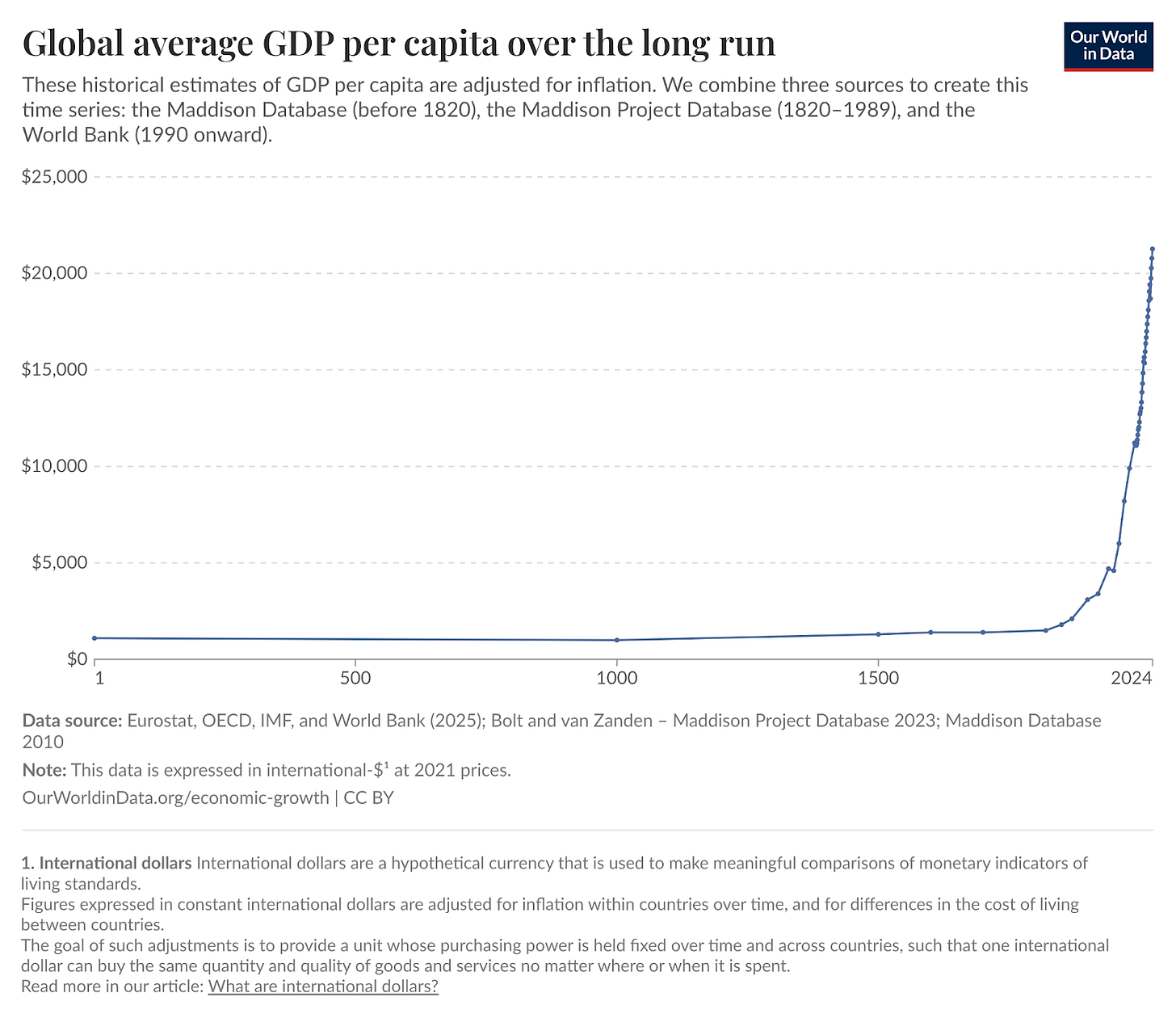

We can see it with GDP per capita, which increases all the time, showing that our ideas get better and better, and they allow us to make more with less.

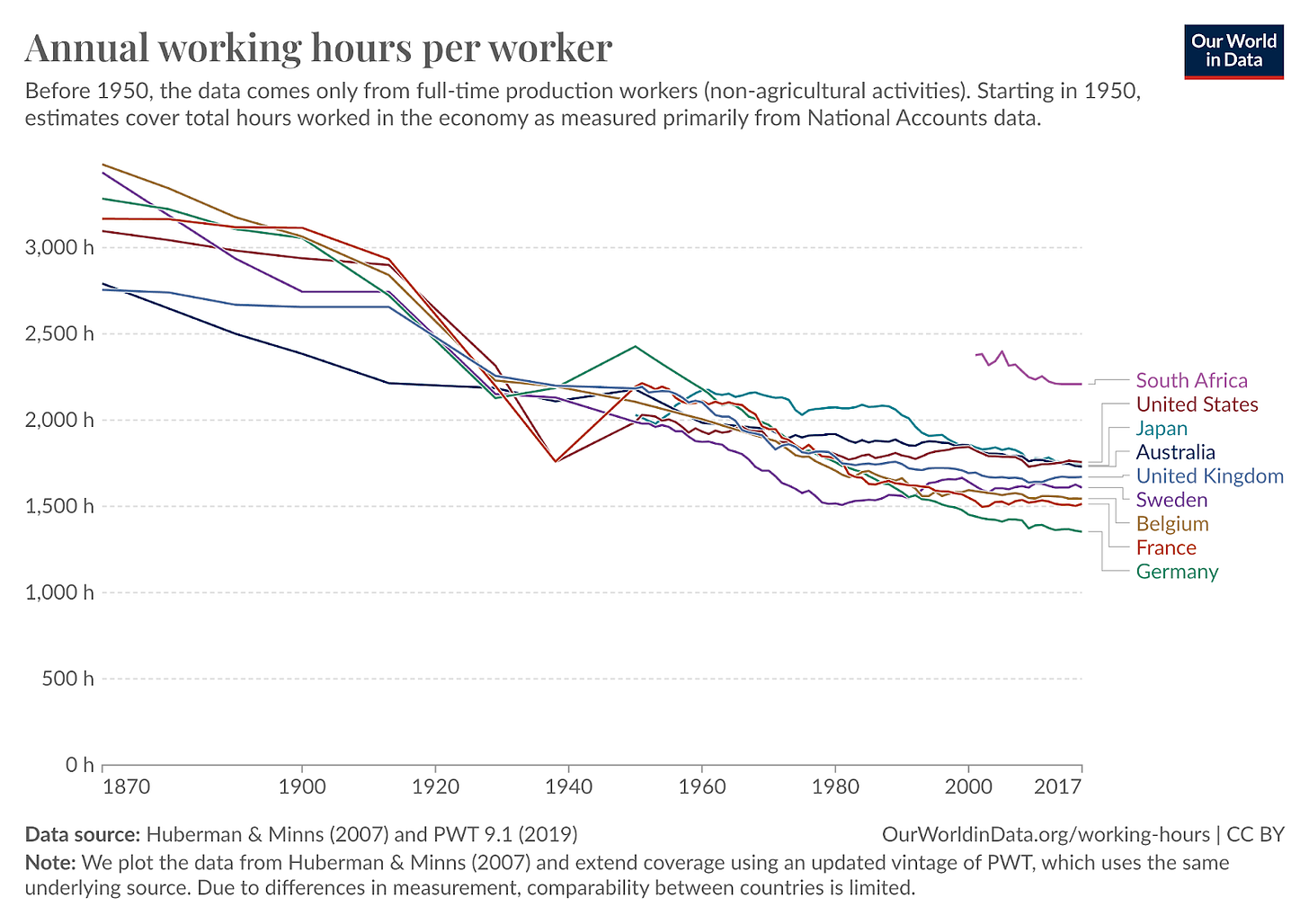

We do that while working less.

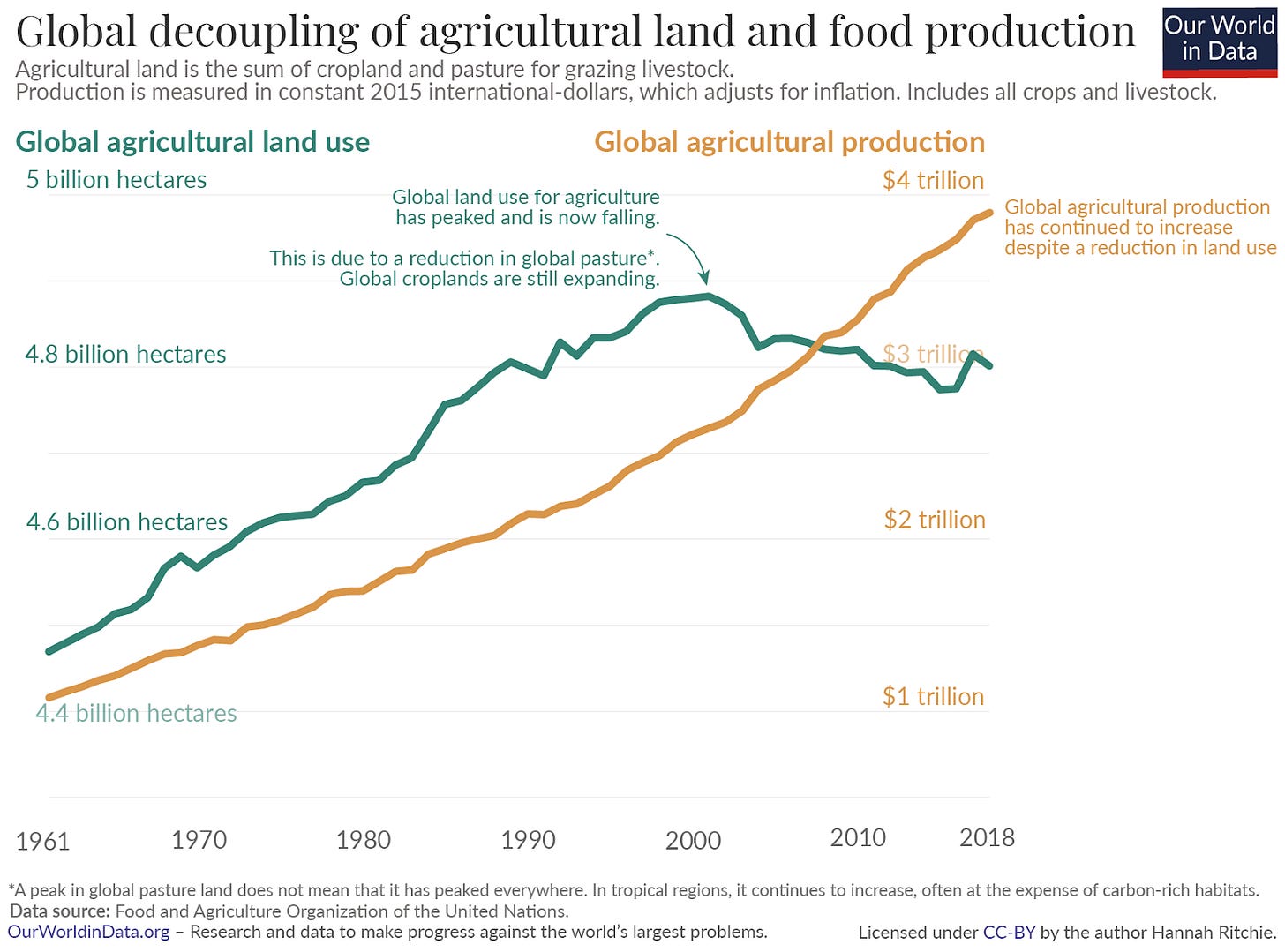

We produce more food with less land.

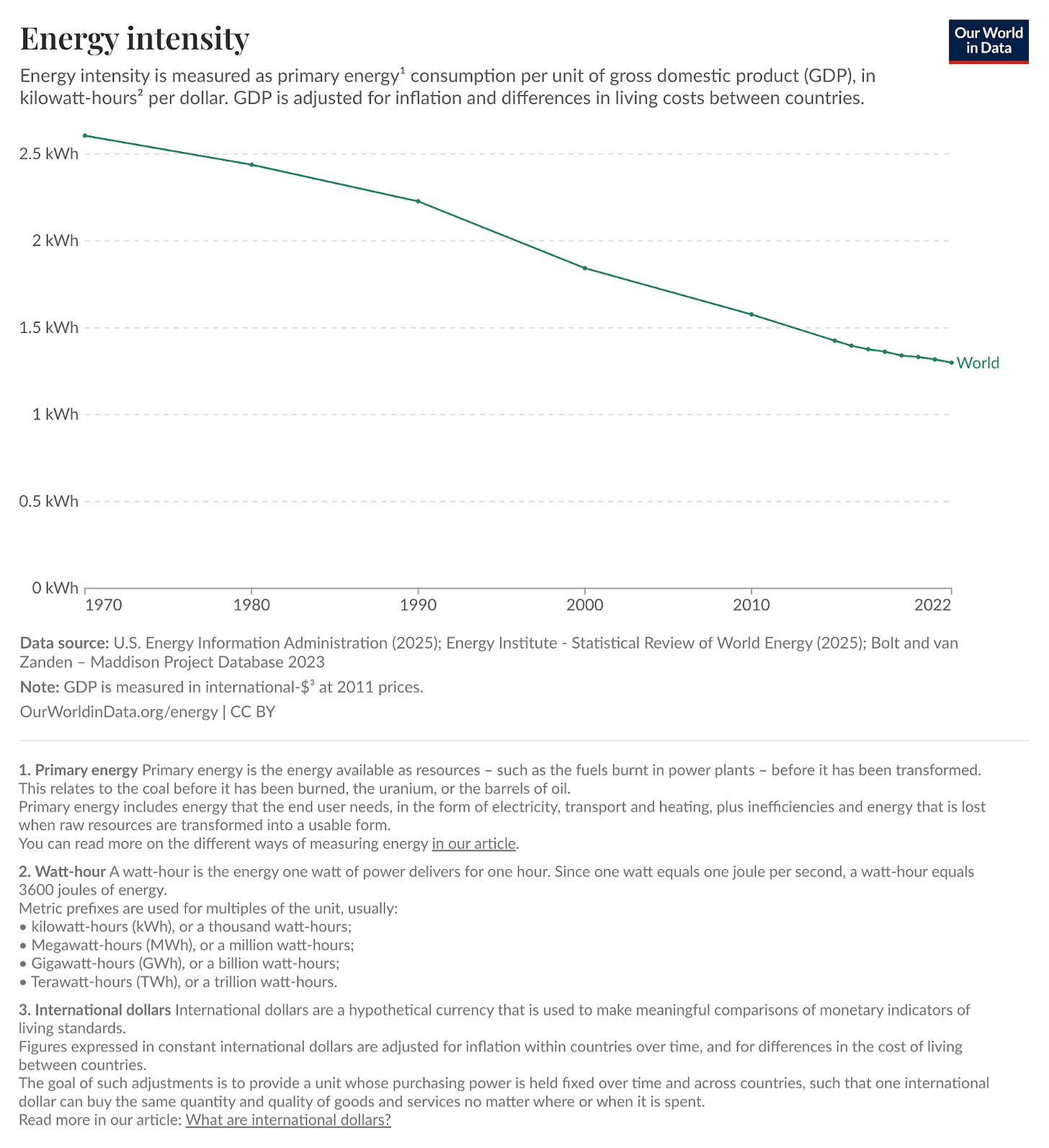

We generate more and more wealth with every watt.

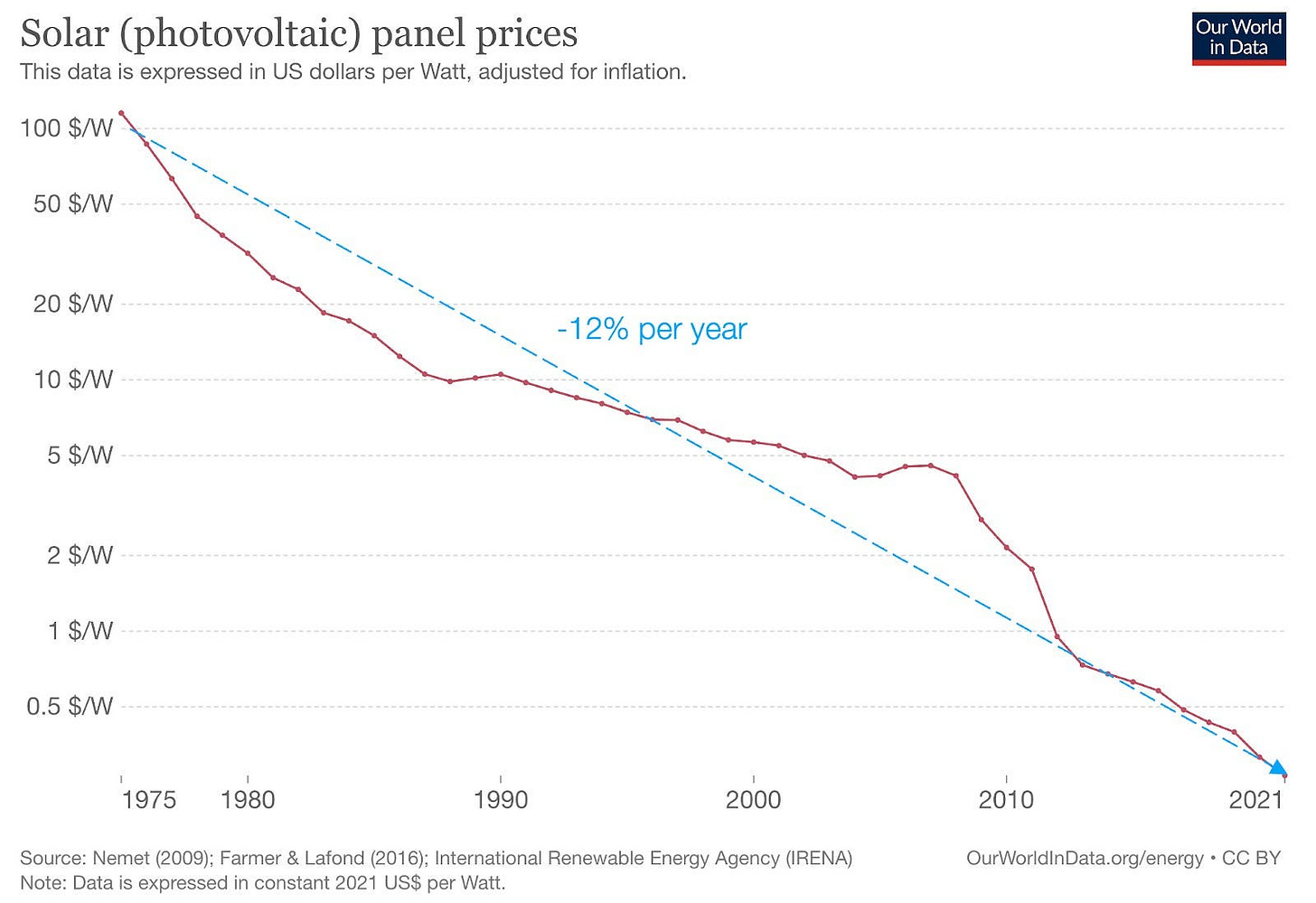

Solar panels are getting better all the time.

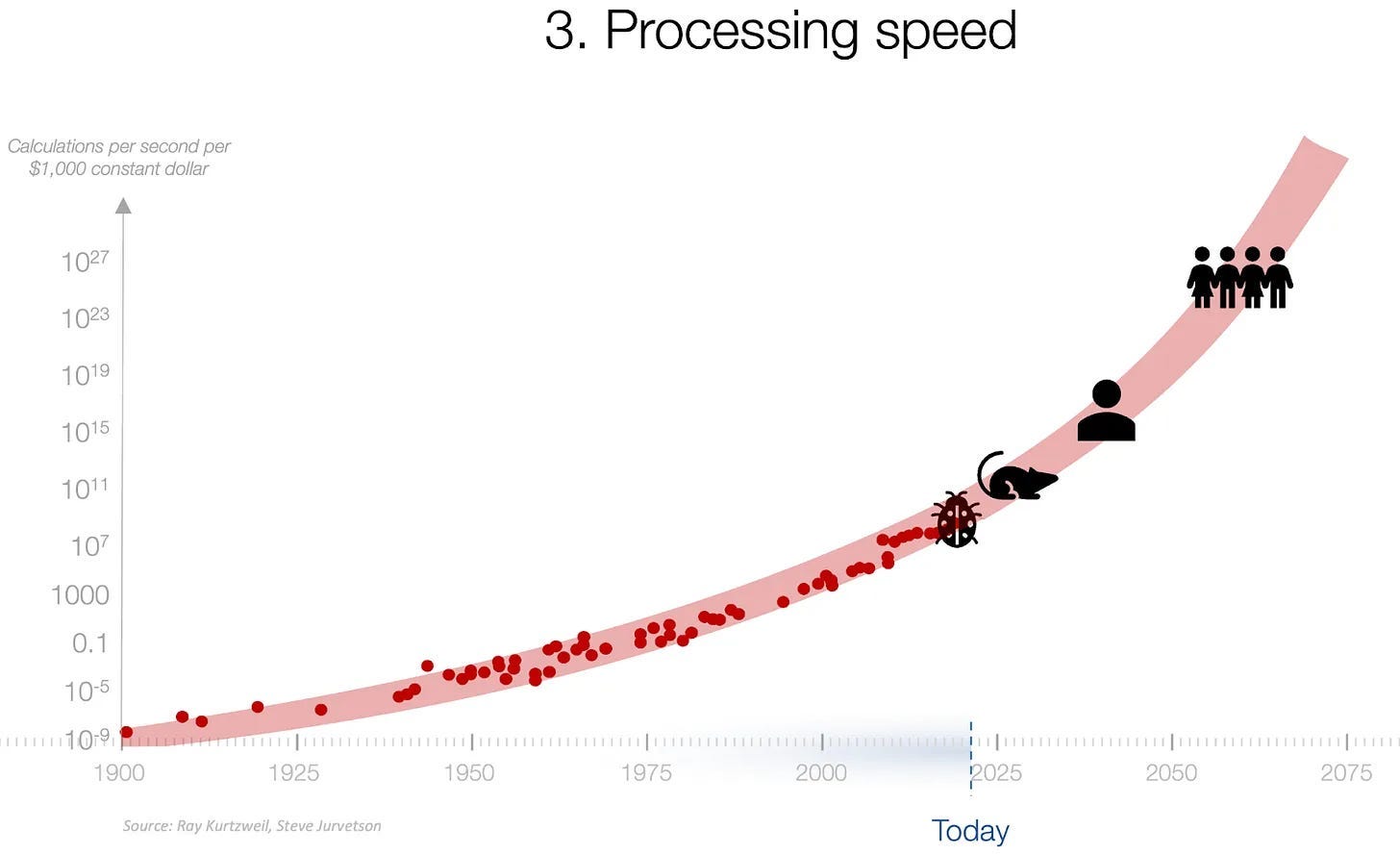

Every two years, we double our capacity for intelligence, and this is accelerating with AI.

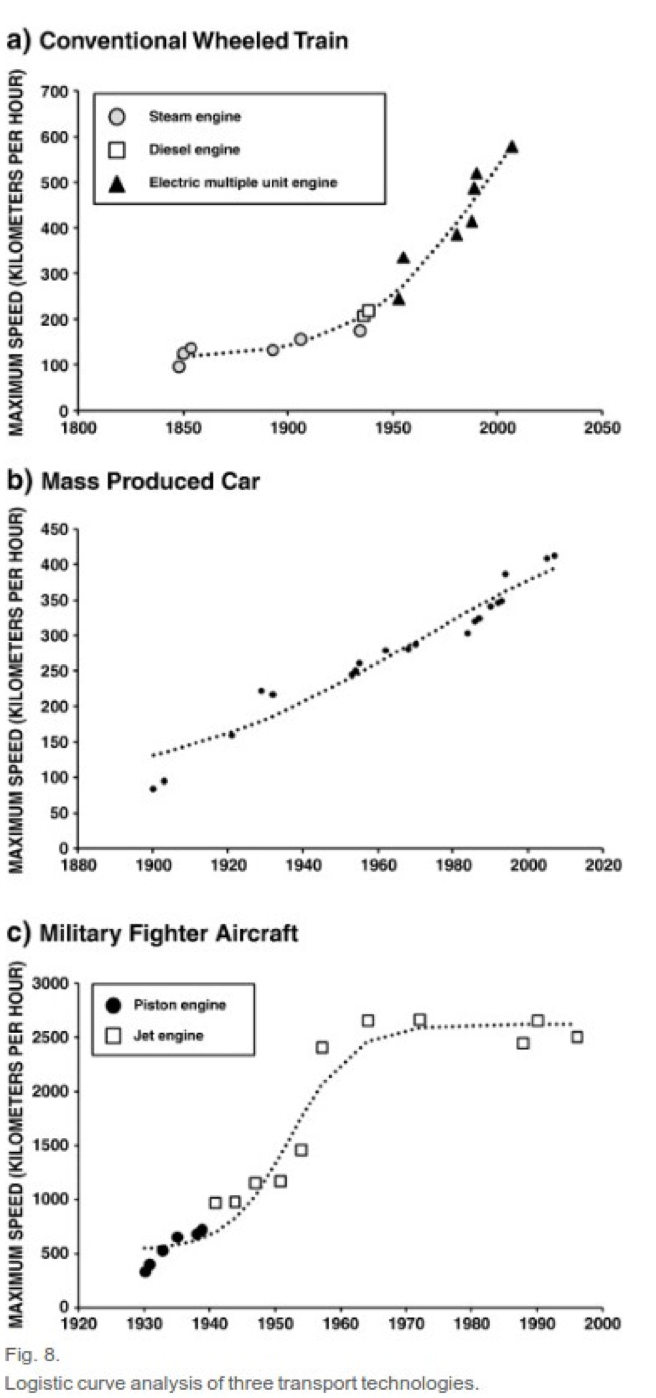

Transportation speeds get better.

We see it with every system in the world: If we are free to optimize it, it gets better, and we get more with less.

That’s what abundance is: We can create a world of plenty. We can take what exists and make much more with it. Our only limit is our intelligence.

Why, then, are so many people fearful of running out of everything, of exhausting the Earth?

The Fear of Ourselves

Part of it is our evolution: We evolved in a world of scarcity. That’s the other side of the coin: We can only get better because we were worse. As we evolved, we never had enough food, we never had enough shelter, enough water, enough safety. And so when we see resources, we crave them, we protect them, for fear that we will exhaust them—or worse, somebody else will take them from us.

Another reason is history: We used to love technological progress.

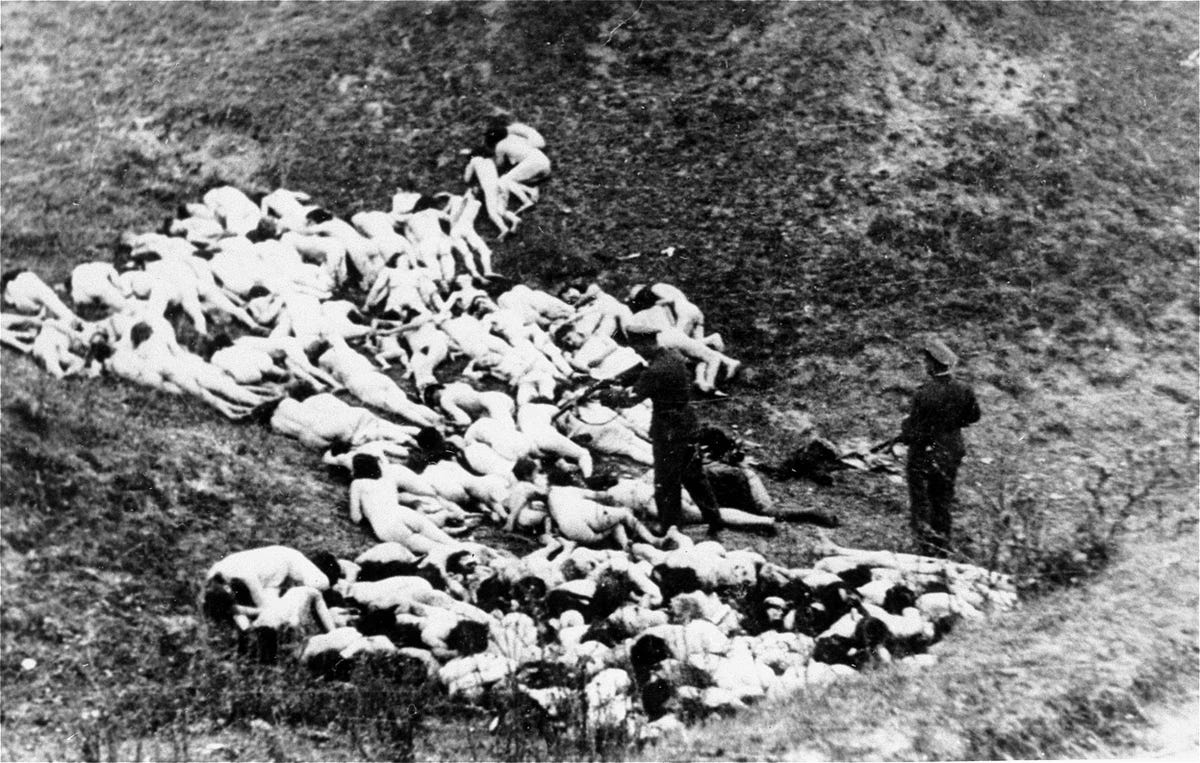

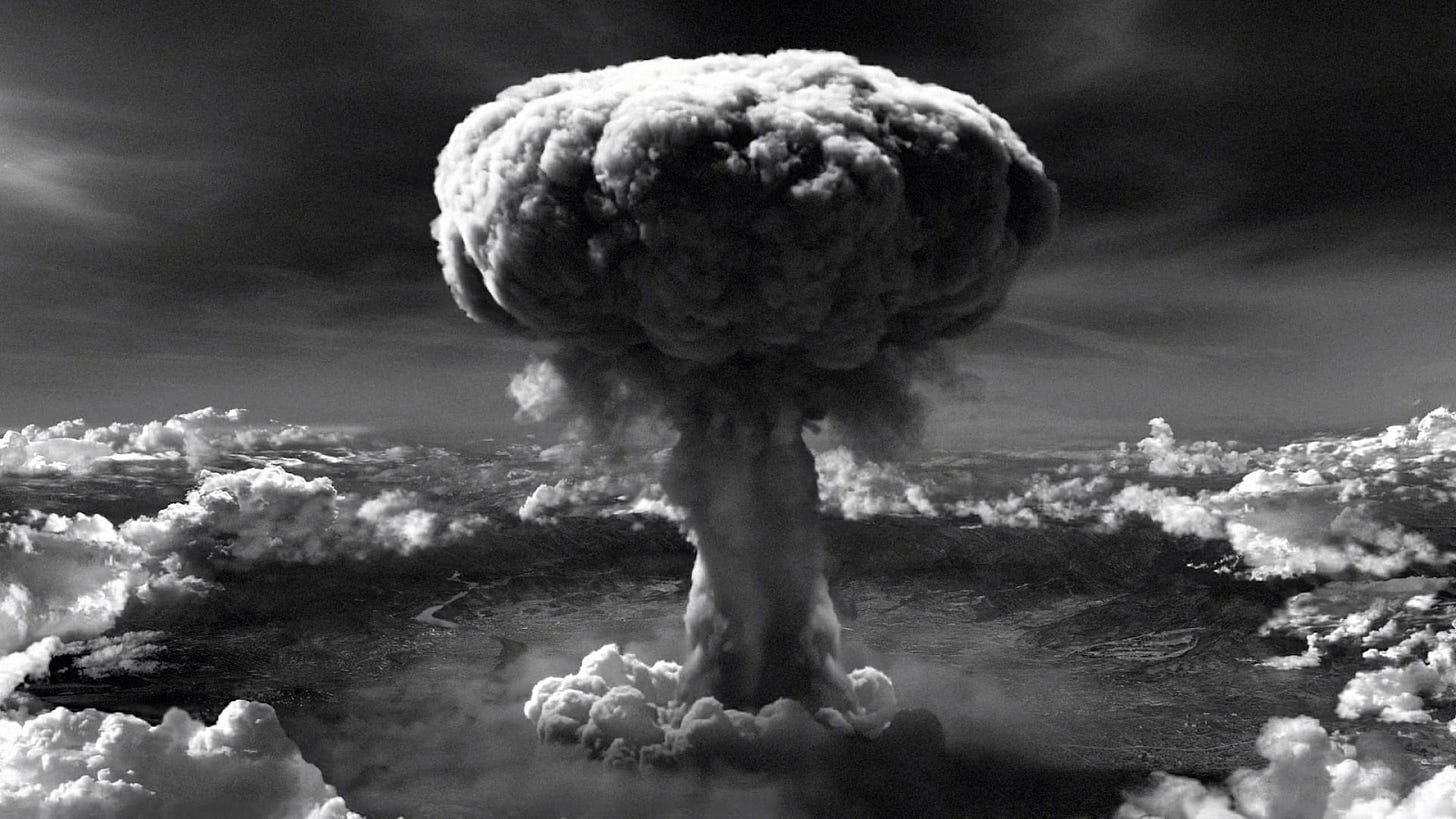

But then, we used it to kill each other.

WW1 was bad, WW2 was worse.

We discovered the power we held, and we grew scared.

And we saw it in the environment, too. As we followed the motto of The solution to pollution is dilution, we dissolved all our pollutants in nature until we realized that it was not, in fact, the solution.

Sustainable ➡️ Abundant

Since then, we’ve overcorrected. That’s good! Humans work like a pendulum, overcorrecting over and over again until we reach the optimal point. That’s why forest area is increasing in Europe.

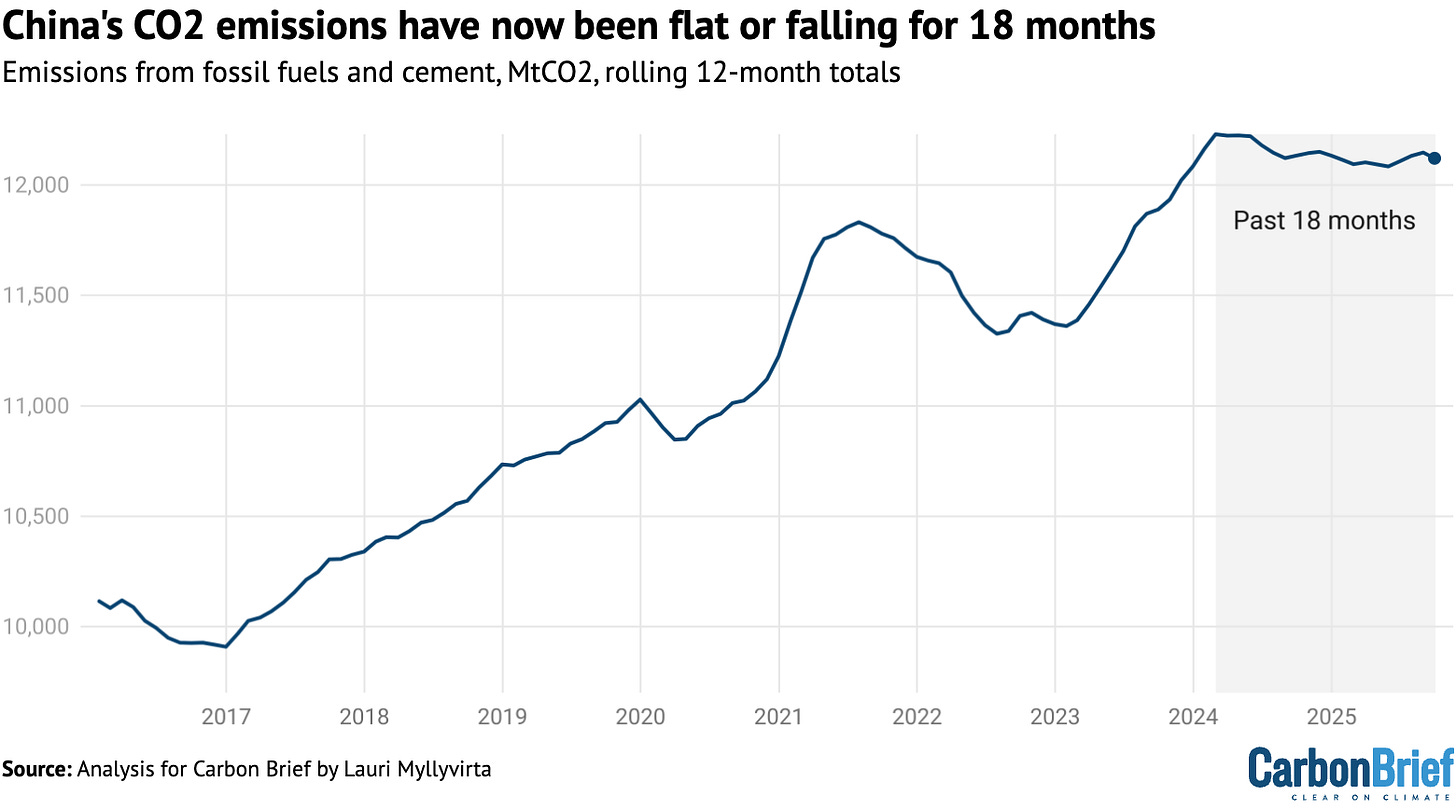

That’s why China might have reached peak emissions.

From a chaotic planet evolved life.

From life evolved intelligence.

Intelligence birthed humans.

Humans accelerated intelligence.

We created culture.

We created societies.

We created the Internet.

We are creating gods.

The Earth is no longer a chaotic system with limited resources that we barely understand and which we must protect to make it sustainable. It is a machine that we understand pretty well, that we’re getting better at improving every day when we treat it as a system.

Fishery depletion is not a problem of eating too much fish. It’s a problem of eating too much wild fish.

CO2 emissions are not a problem of too much fossil fuel burning. They’re a problem of rapid temperature increases, which can be reversed.

Fresh water scarcity is not a problem of drinking too much. It’s a problem of getting the water from unsustainable underground wells instead of from the sea.

The Earth is not a stable goddess, it’s a system, and it has changed dramatically over its history—much more wildly than we’ve ever experienced.

As we mindlessly tinkered with the planet, our excesses surfaced these mechanisms. We thought the answer was “Don’t touch it!” But that lesson is outdated. “Sustainable” is defeatist because it says “I don’t know how this works, I can’t know, just don’t touch it.” It’s a bit like an old religion that tries to placate the gods.

But all this tinkering revealed the mechanisms of the Earth. Now, we know much better how it works. And that’s why we can finally optimize for abundance. We can engineer the world. We can have more food, more forests, more money, more people, more animals, more houses, more nature. But only if we strive for abundance instead of sustainability.

The solution to pollution is profusion.

Currently a hypothesis

Solar panels are made primarily of silicon, which is basically sand. That’s also the main component of transistors and chips, which make our computers. And we’re using computers to build gods: artificial superintelligence (ASI).

I wanted to add a comment to your story.

For thousands of years obsidian was traded over long distances. It was in many ways to human being prior to 5,000 BCE what oil is to us now.

There was a crisis around 5,000 BCE. Readily available sources of obsidian had become depleted. Obsidian became scarce and, consequently, expensive.

Humanity did not become extinct. Tools made of copper were used as a substitute for those made of obsidian, Then bronze. Then iron. Then steel. We haven't looked back.

The moral of this story is that we should worry less about depleting resources on which we depend and considerably more about discouraging or outright preventing the innovation that encourages substituting depleted resources with those we still have.

There are so many natural systems that we barely understand, especially in the field of health and medicine. And there are so many incentives to flatten the models we do have and oversimplify how we intervene in these systems, often causing harm.

For example, we only just confirmed a decade ago that Pitocin, the synthetic hormone that hospitals give almost all birthing mothers to prevent or treat hemorrhage or in higher doses to induce or intensify labor, obstructs mother-baby bonding, causing postpartum depression. Oops!

Evolution spent all this time figuring out how to make the birth process jumpstart maternal instincts and motivation, especially for mammals, and especially for comparatively premature human infants. And then we go and mess up those hormones and make motherhood harder and less fulfilling. Then we wonder why people don't have more kids.

And hospitals probably won't change those protocols, because the non-pharmaceutical ways of boosting the brain's endogenous oxytocin that drives labor, prevents hemorrhage, and causes bonding are expensive or impossible to implement in hospitals. They basically amount to making sure the laboring mother feels at home and constantly supported in person by safe, snuggly, and familiar people, not bothered by unfamiliar places or people, lights, noises, paperwork, or hostility. Those things are what make hospitals operate efficiently, but they're what tank endogenous oxytocin production and labor progress and safety. That's why, in developed countries, and for low-risk mothers, home birth with a licensed midwife is safer than hospital birth. Regulatory capture is why home birth midwifery is not more common in the US.

Of course I appreciate the field of medicine in general, including prenatal ultrasounds, screening tests, Pitocin used to stop hemorrhage when it does occur, etc., all of which home birth midwives also do as a matter of course. High-risk interventions like Pitocin or C-sections are sometimes the best solution, they're just used more often than ideal because we're sabotaging labor earlier in the process.

My point is that some complex natural processes, like labor, are poorly understood, poorly taught (unlike midwives, OBs are surgeons foremost and have typically never witnessed an entire labor without drugs), and very inconvenient to scale for financial efficiency. Birth is my area of expertise, but I'm going to remember Gell-Mann and infer that there are many other such systems that we could inadvertently mess up.

Evolution has figured out some things that we haven't. We can certainly make some improvements - maternal and infant mortality is lower now than it was 10,000 years ago - but we need to always refer back to nature to make sure we're preserving the good as well as we can while preventing the bad. That requires ongoing scientific inquiry and a foundational respect for nature.