Pax Mercatus

I obsess about what will happen to society in the coming decades, and one of the biggest trends is the weakening of the nation state. So how can we better foresee what will happen? By understanding how we arrived where we are. That means understanding history: Why different political systems emerged when they did, and why. In Internet Will Kill Nation-States, we explored how communication technologies destroyed the power of the Church and Feudal lords and ushered the nation-state into existence. From that, we concluded that nation-states would be weakened by the Internet.

But that picture is not complete. Over the last few months, I’ve been studying this more. Why was the feudal system the rule of the land back then? What was the role of the Church in preserving the feudal system? And was the arrival of the printing press the only big factor in replacing these systems with nation-states or were there others?

These are the themes we’re going to explore in the coming articles. As we do, we’ll come to understand some other things, like how the Industrial Revolution didn’t really start when we think it did, and how the world is likely to evolve in the coming decades as we transition away from nation-states.

Why the Feudal System?

To start, we need to understand why the feudal system was prevalent in Europe in the Middle Ages, emerging little by little after the fall of the Roman Empire.

Imagine you’re the king of France, Spain, Poland, England, Russia… You reign over hundreds of thousands of square kilometers, made up of forests, mountains, and endless fields of crops. It takes weeks or months to go from one side of the country to the other, to visit the fields that grow the wealth of your country. How can you control all the land? How can you inspect it, rule it, or tax it efficiently?

This last element is probably the most important: Money is power, so kings like collecting taxes and subordinates dislike paying them. Since at the time, most wealth generated was food, subjects had a huge incentive to lowball food production. How could kings know if they had been lowballed? It was not easy. Look at this:

This is a standard medieval manor area, with the manor, the church, and the hamlet in the middle. Look at all the field stripes, the pastures, the meadows… The setup is complex. Why the stripes, specifically?

There were different types based on the owner and function, but crucially every farmer had to tend to several stripes across the land. Why? Because this mixed some good fields and bad fields and diversified the risk in case of a bad harvest in one area or the other. In other words: farmers tended to different fields because their productivity was very heterogeneous, and it was hard to predict the production of each piece of land.

If it was difficult for the locals to forecast land productivity, how well do you think the remote king could forecast it?

Now add different levels of rainfall across different valleys, different flows in the local streams, different quality of the irrigation systems, and the food production of different regions was very hard to predict. Which means locals could lowball their reported production. How could the king fight this?

The Geometry of Feudalism

As a ruler, you’ll want to put your capital as close to the middle as possible, so you can ride anywhere as fast as possible. But even then, you can’t be everywhere at once. It takes weeks or months for you and your retinue to travel to one corner of your kingdom to inspect it. Then, you need to do the same to go to another corner of your kingdom. And then yet another, and another. Kings were forced to do this! So in fact, they didn’t really have capitals. Their court was itinerant. Spain’s rulers only settled in Madrid as a capital in the mid 1500s. The Holy Roman Empire—which ruled mostly over present-day Germany—never established a capital.1

Of course, wherever you’re absent, people start lowballing. So even if you move around, you still need somebody to make sure every region is pulling its weight. You need to delegate.

Your dukes have a similar problem though. They don’t have full visibility on their land’s productivity. So their duchy is also broken down into smaller pieces that are delegated to their subordinates, such as counts or earls.2

You end up with a fractal structure—going all the way to barons and knights—that is reminiscent of management structures in today’s companies.

There are only so many hours in the day and days in the month, so the surface area that small feudal lords could cover was small. That’s how you get barons and knights, who oversaw farmers directly.

Of course, lower lords had an incentive to record as much production as possible to tax it, but then report up as little as possible.

In other words: It’s because wealth was generated across big surfaces that were hard to oversee that we ended up with this management structure.

This, in turn, made the sovereigns at the top quite weak: They could not oversee each duke, count, earl, baron, or knight. The same was true at every level. So you ended up with low-level knights and barons who were quite independent and powerful.

Through the Middle Ages and the Modern period, a series of innovations consistently weakened the low-level feudal lords and concentrated power higher and higher up the chain.

The Agricultural Revolution

We think of the Dark Ages, broadly between 500 and 1000 AD, as a time when nothing happened. That’s not true. It was just that after the fall of the Roman Empire, and everything was in disarray. Everything had to be rebuilt from scratch.

When most of your economy depends on farming, your innovations will be focused on farming. Between 600 and 1000, the plough evolved continuously, so that by 1000, Europe had the heavy plow:

The plow turns over the soil.

Pulled by oxen, it allowed farmers to plow a much deeper surface of the ground than they could before.

This buried the exhausted soil and brought more fertile soil to the surface, burying weeds so that they decayed in the ground and became fertilizer for future harvests. This increased yields, especially in Northern Europe, which had very fertile soil that could not be easily farmed because it was too heavy and filled with water, impossible to plow with more basic machines.

It also allowed the fields to be plowed only once rather than twice,3 but this required pulling much harder on the plow, which dug much deeper in the ground. Sometimes, a row of eight oxen (cows) were needed to pull the plow.

Enter horses. Systematic horse breeding stopped after the fall of the Roman Empire, and their genetic specialization decayed. But people started breeding them again, and over the centuries, they became more and more efficient. So much so, that by 1000 AD they were strong enough to replace oxen pulling plows. Before, a team of eight oxen could work half an acre per day. A team of only four horses could plow a full acre per day, or four times more. This compensated for the higher feeding need of horses.4

Another innovation is the horse collar. Before, horses pulled plows with their gait and throat.

These straps pressed on the windpipe, restricting airflow and causing suffocation. The pressure on the jugular veins impeded blood flow. The horse collar rests on shoulders, allowing the horse to pull with its hindquarters. With this, horses were able to pull three to fives times more than without it, and 50% more than oxen.

In nature, horse hooves are hardened by their daily long distance walking (up to 80 km / 50 mi) on hard ground. Domesticated horses had softer hooves because they walked much less, and Northern European soil (especially that of farms) is softer. The result was that hooves broke more easily until the horseshoe was invented and became widespread in Europe in the Medieval Era.

Put all these things together,5 and suddenly you could plow substantially more soil, substantially faster, and produce substantially more food.6

One way to think about this is as a series of energy inventions: The more energy-efficient horse could transfer more energy to the collar, which efficiently transferred it to the plow, which efficiently transferred it to the ground, increasing its productivity.

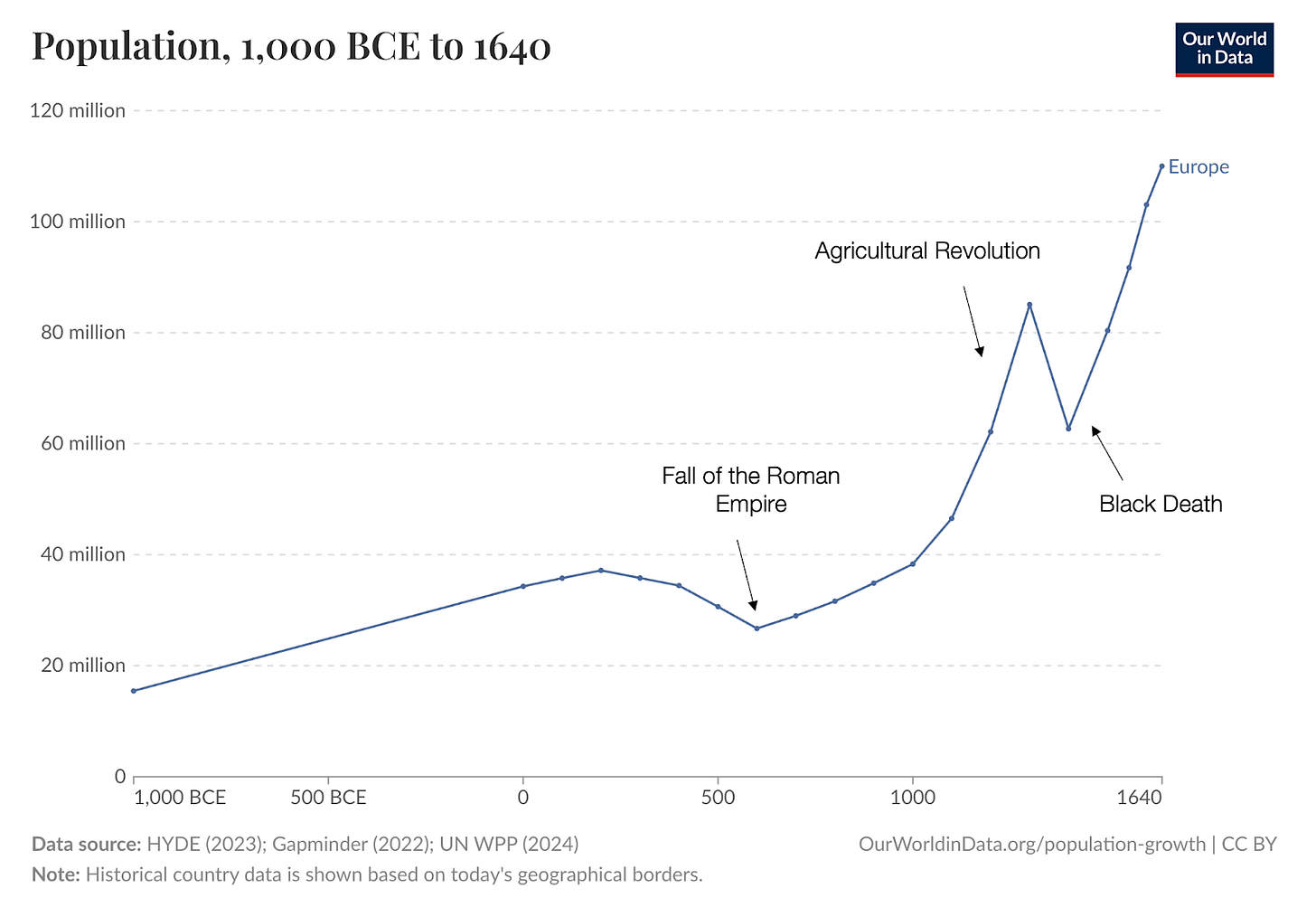

Better harvests gave us more food. This allowed us to dedicate some more land to grow fodder for the horses, which in turn had more energy to pull the plows harder and for longer, in a virtuous cycle that generated a bounty of food. Then, this happened:

The population of Europe exploded, especially in Northern Europe, where the benefits brought by the plow were spectacular given the soil. Suddenly, in many parts, there were more people than were needed to tend the farms.

This was exacerbated by other innovations, like better mills.

They existed in the Roman Empire, but their use expanded considerably during the Middle Ages.7

Mills ground grain efficiently, so that a job that took a family many hours per week on a manual quern could be achieved in minutes.8 This meant an even greater surplus of workers.

Where did they all go? To the cities.

This urbanization was extremely important. In cities, citizens could specialize their labor. This increased the overall productivity of the economy, making everybody richer. One of their occupations was especially relevant: trade.

Trade networks appeared across Europe, allowing every participant to get richer. The more trade there was, the more each city could specialize in different goods—cloth, iron, cheese, fish, you name it.

Trade created the merchant class.

And the merchant class was an alternative center of power to that of feudal lords and the Church.

Also, while farming requires surfaces, cities are points. It’s hard to oversee surfaces, but it’s easy to oversee points. They are chokepoints for the generation of wealth, which means they’re much easier to tax.

This increase in economic activity and taxability made the top lords richer than they had ever been.

The Transportation Revolution

Remember how we said horses had more energy to convey to the plow? They didn’t just convey it to the plow. They also pulled other things: barges over rivers, and carts over roads and rails.

Oxen were too slow and weak to pull all these things over long distances. Horses were twice as fast and more energetically efficient, but they weren’t sufficient to pull all the goods needed for a trading economy. However, with fodder, they could. Suddenly, they could pull ore from mines, transport goods over short roads to the river, and then benefit from the 5x to 10x lower transportation costs over navigable rivers, which frequently required horses to pull barges.

As I shared in Starship Will Change Humanity Soon, when you decrease transportation costs by 2, you multiply the distance to which you can transport things by 2, which increases the surface to which you can transport things by 4.9 In other words, you can reach 4 times more cities. Add to that the network effects of trade, where the value of a network is the square of the number of nodes, and you get an increase of 16x in the value of trade.

Combine these factors, and your value generated increases by at least 100x.10 Unsurprisingly, this explosion in trade and wealth was noticed by kings, so they invested heavily in infrastructure. This is when the development of roads, bridges, and canals start accelerating.

Here’s another illustration of this principle. The best positioned cities became extremely powerful, especially those at the confluence of rivers and trading seas. And among those, a few were very special: Venice, Milan, Amsterdam, Ghent, Hamburg, Strasbourg… What do these have in common? Canals.

When road transportation is 5-10x more expensive than water transportation, the cost of transporting goods a few kilometers inland can quickly overwhelm long distance water transportation costs. So in cities that were on rivers and on the coast and where the city itself was made of canals, the transportation advantage was so powerful that trade naturally converged there.

This, by the way, is also why nearly all big European cities are traversed by a river.

Pax Mercatus

Now imagine that trade starts growing on a river. Naturally, you’re going to have bandits trying to steal your goods. This disrupts trade and makes everybody poorer. So the king11 pushes to enforce peace in their part of the river. The more peace he achieves, the more trade there is, the wealthier the region becomes, the more money the king12 can tax, and the more powerful he becomes. Since rivers were the main axis of long-distance trade, kings started enforcing peace along the length of these rivers. It is not a coincidence that many of the strongest kingdoms emerged along the biggest European rivers.

You can see this mechanism at play: When long-distance trade becomes possible, strong players will try to guarantee the safety of trade so they can tax it. The more they succeed, the more trade there is, the more wealth, the more taxes, and the more powerful they become, further expanding their power.

At the same time, since they control an area of trade, it makes sense for them to invest in infrastructure to further increase trade, including roads, bridges, canals, river embankments, ports. The more they invest, the richer they become, investing further, and becoming even richer.

This whole process needs force to begin with, and money to invest, so only the biggest kings, who controlled the most rivers and cities, could afford these investments, further centralizing the power.

I call this process Pax Mercatus: Peace through trade, backed by force. The same thing happened in the Mediterranean, when Romans built the Pax Romana on the top of sea sailing ships. The empire was only as big as one month of travel distance from Rome—which is why they also built so many roads.

You might also know Pax Mongolica, based on the silk road that the Mongols reopened after they conquered everything from Poland to Korea, on the back of the speed of their horses. And of course, Pax Americana, the peaceful period after WW2 in which global trade exploded based on the maritime peace guaranteed by the American Navy.

We saw it somewhere else in the transition from the Medieval Era to the Modern Era.

Age of Discovery

When Portugal finished its Reconquista against the Moors in the 1400s, it had nowhere else to go but to the Atlantic Ocean. So that’s what it did. It started improving its navigation technologies until it was able to sail below Africa and reach India.

The goal was always to reach India for trade. Over time, it built a coastal empire across Europe, Africa, Asia, and America, to safeguard its trade. Spain did the same with America.

Of course, when you have trade, you attract bandits—in this case, pirates. And pirates are bad for business, so the states invested heavily into fleets to eliminate the pirate threat.

Of course, the Atlantic Trade was even more concentrated than other types of trade, because there were only so many deep water ports on the Atlantic Coast of Europe, and it was desirable to concentrate their trade and infrastructure. This graduated into another league of cities like Sevilla, Cadiz, Lisbon, Porto, Bordeaux, Nantes, London, Amsterdam…

These cities could be even more easily controlled and taxed by sovereigns than farmlands or even more distributed cities. Here you have another Pax Mercatus (or Mercapax), this time at the global level.

Except seas are open, so rival countries challenged each other’s fleets, and that continued for centuries until the British prevailed in the 1700s, creating their Pax Britannica.

From Transportation to Physical Control

It wasn’t only traders who could travel faster and for cheaper. Kings could too. They could reach far-flung regions in a matter of days instead of weeks, keeping their subordinates at bay. And if they misbehaved, they could send their armies and navies, who could quickly reach their destination, and could also be better provisioned through better logistics. It’s unsurprising that Absolute Monarchy emerged after the end of the Medieval Era.

Takeaways

So here’s what happened:

Centuries of technological development during the Dark Ages (~500-1000 AD) gave us innovations like the heavy plow, stronger horses, the horse collar, and better mills.

These innovations increased crop yields, giving more food, and the population exploded.

This created a surplus of people that didn’t need to tend to farms. So they could specialize in trades. Specialization increased the productivity per person, and hence wealth.

All these people didn’t stay on farms. They went to cities, growing them.

Cities benefit from network effects, further increasing the value created.

Cities are points, so they’re easy to control and tax by sovereigns—unlike farms, which are surfaces.

Rivers are in between: They’re lines. Harder to control, but it was worth it, because the more of these rivers that could be controlled, the more peace could be guaranteed along their length, and the more trade there could be.

This created a virtuous cycle of more peace, more trade, more taxes, more powerful kings, more peace…

Another feedback loop was around infrastructure: More taxes, more infrastructure, more trade, more taxes… Which decreased transportation costs.

Fodder and better horses also lowered transportation costs over rivers and land.

And oceanic navigation lowered it in the oceans.

Small reductions in transportation costs can generate massive wealth, so all these technologies combined caused massive windfalls across the continent.

All these virtuous cycles fed into each other, accelerating wealth creation: transportation, sovereignty, trade, urbanization…

And all this wealth could now be taxed by the biggest sovereigns. And since there was better infrastructure and lower transportation costs, they could move their armies much faster, thus increasing their control over their land.

This gave them all the control they lacked during the Medieval Era, and that allowed for the creation of huge states. Combined with the emerging concept of nations, history witnessed the emergence of the nation-state.

Berlin was just the capital of Prussia, and as such became the first capital of Germany.

This breakdown was nearly MECE, mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. Not quite, because lords could lay claims to the same pieces of land, and borderlands frequently played off lords against each other for benefits. Similarly, early on when the population was low (in the Dark Ages, about 4 people per km2), lots of land was uninhabited, especially woodland. Through the subsequent centuries, a lot of it was cleared for more farmland, creating the landscapes Europeans know today.

Before, they had to be cross-plowed too.

They needed grain as well as pasture.

There were other technologies that contributed, but this article is not an intense review of medieval agricultural technology. An example is the three-field crop rotation system, which allowed for two harvests a year instead of the single one of the two-field rotation. This reduced crop failure risks, and since one of the rotations included beans and legumes that fixate nitrogen into the ground, soil fertility increased. Additionally, this allowed for fodder for horses. Without it, you couldn’t have many horses on your field. Since the three-field crop rotation requires more constant rain through the year, it worked well in Northern Europe, but less so in the south. More here. Another technology was putting the draft animals in several rows rather than a single row, which allowed them to pull the plow more uniformly.

Fun fact: The heavy plow allowed only one pass to plow the fields, but it was also harder to turn the animals, so it made sense to make longer passes before turning. This is the origin of the long strips of farm that you saw earlier, in the plan of the Medieval manor.

Charlemagne ordered, among other things, that a mill get built in each of his estates.

I can’t find the source for this anymore. I asked ChatGPT, and it can’t give me a definitive source, although all the sources it gave me are broadly aligned. This is probably directionally correct.

A surface is the square of a line.

Let’s take 5x as the cheaper transportation cost. That means increasing by 5x the distance traveled, so by 25x the number of potential nodes reached, and 25^2=600.

Or the regional lord, or one of the cleverer bandits, we’ll talk about that in the future.

Usually it was kings, but sometimes queens. Kings for simplification.

One thing I appreciate from this article is that none of these developments were planned. They evolved out of small, local choices. It is in retrospect that we can see the forces that shaped the world. (That's not the best way to say it, but I think my meaning is clear.)

Just wanted to say thank you. This read was a blast. Really liked the easy explanation of the Dark Age transition to High medieval age and how new technology was indeed important, especially for growth in regions that were not relevant during the Roman age, but later on even more (like Northern Germany - I am from Western Germany and we have great land for agriculture here).