Standing on the Shoulders of Gnomes

We could have instant drone delivery.

We could have flying cars.

We could have energy too cheap to meter.

We could forget about diseases.

We don’t because we’re too scared.

Ankylosaurus Inc

Svieta stops. The lights turn back on. She turns around to face the room.

They’re looking at each other around the table. A couple of them are murmuring in the corner.

“Well? What do you think?”

All heads turn to the CEO.

“This is a fantastic idea! We should do it.”

Then the sequence begins:

“We should schedule a meeting to go over it with production. Their annual roadmap is settled, and they’d need to see how this fits into their schedule. You should talk with Mohammed.”

“I heard they’re doing something similar in Sales. They hired their own small engineering team to do it. We should coordinate.”

“The GM from Business Unit 2 has validated a new checklist for this. If we want to make this happen fast, we should get going on that list.”

Two months later, Svieta has founded her own company, Velocicaptor.

Three years later, she eats Ankylosaurus Inc’s business.

Who said the following and when:

Provide a way to instantly share digital photographs with others anywhere on Earth—but only with those who you want to see the photo.

Instagram? In 2010? No. Kodak in 1996. But Kodak had 150,000 employees back then and Instagram had 12 when they got acquired.

We consistently see big corporations replaced by startups. The BigCos are slow to learn and execute. They can’t make decisions. The startups are fast and nimble and can outmaneuver their pachydermic nemeses. Why?

There are many reasons1. But one of them is what I call Metcalfe’s Antithesis:

When you’re small, everybody is in a room and can quickly align on the big decisions. When you’re huge, you can’t do that. But people still need to coordinate with other teams. So you have incessant meetings with dozens of people, there are processes and checklists for everything, and decisions take forever.

This is our society today.

Standing on the Shoulders of Gnomes

We stand on the shoulders of giants.—Newton, quoting John of Salisbury, quoting Bernard of Chartres, probably quoting some other gnomes before him.

When Isaac Newton said he stood on the shoulders of giants, he meant that many great thinkers before him had accumulated the knowledge of humankind, and that he was just adding a little bit to the edifice.

That Great Man theory again, where science and history would be stagnant if it weren’t for these magic saviors who came to rescue us from our mediocrity.

Reality is quite different.

Romans built the Colosseum more than a thousand years before we discovered calculus. They relied on rules of thumb for their arches. These, in turn, were the result of hundreds of years of trial and error.

Every time a house fell, every time an arch crumbled, every time they passed a building that stood the test of time, ancient architects updated their rules of thumb on what worked and what didn’t.

So when Newton realized how gravity worked, he wasn’t standing on the shoulders of a few giant discoverers. He was standing on the shoulders of millions of little ones.

Another example: Shakespeare is lauded as a breakthrough writer and creator. Yet every single one of his plays was an adaptation:

This is how everything in civilization evolved. How we went from fire to cooking, from stones to tools, from plants to agriculture, from sticks to spears, trees to houses, grinding stones to windmills, horses to cars, coal to photovoltaic cells, chiefdoms to liberal democracies.

I have definitely seen this working in technology. No single person has an outsized impact on the tech products I’ve participated in. Every single person has added their grain of sand every time they share an idea, debate it with colleagues, build it with their team, test it with customers, learn, iterate, and improve. Millions of people move forward the industry, one argument, one line of code, one AB-test at a time.

This seems true of the entire economy. In most cases, companies are not a made up of a solitary genius recruiting their entourage to support them2. The vast majority of companies progress through their talent and culture, metaphorical ways to refer to people thinking and working together. Maybe you’ve seen it true in your daily experience, with all the colleagues chipping in with ideas on how to do things better? That’s us little people contributing to humanity’s mountain of knowledge.

This has always been true. Billions of people before us looked at their daily tasks and asked: How can I make this better? Some barely improved anything. Others made giant steps. Their learnings accrued into the magnificent edifice of civilizational wisdom.

Most of our progress does not come from famous scientists riffing on each other’s work. We are not a bunch of gnomes resting on the edifice of accumulated wisdom built for us by giants resting on the shoulders of other giants. Progress comes from everyday people like you and me making their work slightly better every day, and building on our shoulders the edifice of human knowledge.

We are not gnomes standing on the shoulders of giants. We are a giant standing on the shoulders of gnomes.

The Price of Progress

The first immutable rule of finance: For more rewards, you need more risk.

If you want to make a lot of money, you need to make riskier investments.

The same is true with startups. Most fail, a few survive, and a handful change the world. Lots of risk, but massive potential rewards.

This is true for all types of science and technology. The more risks we take, the more likely we are to find breakthrough innovations.

This is why your car is so safe today:

Nearly four million Americans have died in car accidents.

Society could have decided: Not a single car death is unacceptable. We won’t allow any car on the streets that can kill somebody.

If we had made that decision, we would still be using bicycles today, and cars would cost $10 million a unit.

But together we decided that the deaths of the few are worth the freedom of the many. We made our peace with road deaths, and moved along.

Car manufacturers would then analyze every accident, every death. Oh wow, this frontal crash pushed the shaft through the driver’s heart. Maybe we should design it so that doesn’t happen again.

Millions have died so you can have a safer car.

The Hidden Cost of Safety

Cars were legal because their usage had such a dramatic value. Everybody wanted one despite the risk they incurred.

But what happens in the situations where the risk is much more tangible than the learning curve? We cop out and just decide to have no risk and no reward.

Let’s stay with cars. If self-driving cars were allowed to have accidents, they would learn much faster than they do today. Naturally, we don’t want them to kill thousands of people. But maybe if we were OK with Teslas killing a few hundred people a year, within a few years we would have self-driving cars and save the 1.3 million people who die in car accidents every year in the world.

Society has made a choice it never realized: It would rather save a few hundred lives today than a few million tomorrow, because the few hundred deaths today make for gripping stories, but the avoidance of 1.3 million deaths doesn’t.

Why Don’t We Have Flying Cars?

There are a few reasons3, but the main one is that we don’t want flying cars to fall from the sky.

We might be ok with a car breakdown every 100,000 km. When they happen, the car stops working, the person parks, calls the tow truck, pays, and gets their car back. But if you have a flying-car breakdown, you fall from 100m, you kill yourself, and maybe take those suntanning below with you. People don’t like the idea.

So maybe the requirement is that flying cars only have a breakdown every 10 million km. That’s 100 times fewer breakdowns than the normal car but with a hundred million fewer global deaths to learn from. You can’t do that easily.

The result is that flying-car companies spend an inordinate amount of money optimizing the safety of their cars, resulting in a price that's prohibitively expensive, so nobody buys them, nobody drives them, the companies don't learn, they don’t make the car safer or cheaper, and nothing moves forward.

As you can imagine, the same reason explains the lack of delivery drones.

Why Don’t We Have Energy Too Cheap to Meter?

Touching this topic is a sure way to get people… go nuclear against me. So let me get this straight: I think the future of energy is probably driven by solar, wind, batteries, and hydrogen long-term storage. And later on, maybe fusion.

That said, we could already have energy too cheap to meter through nuclear fission. The costs would be lower across the board (economic, environmental, safety-wise per KWh), and the benefits huge (near free energy4). The reason we don’t is not because nuclear is more expensive than others. It’s because we’ve made it so.

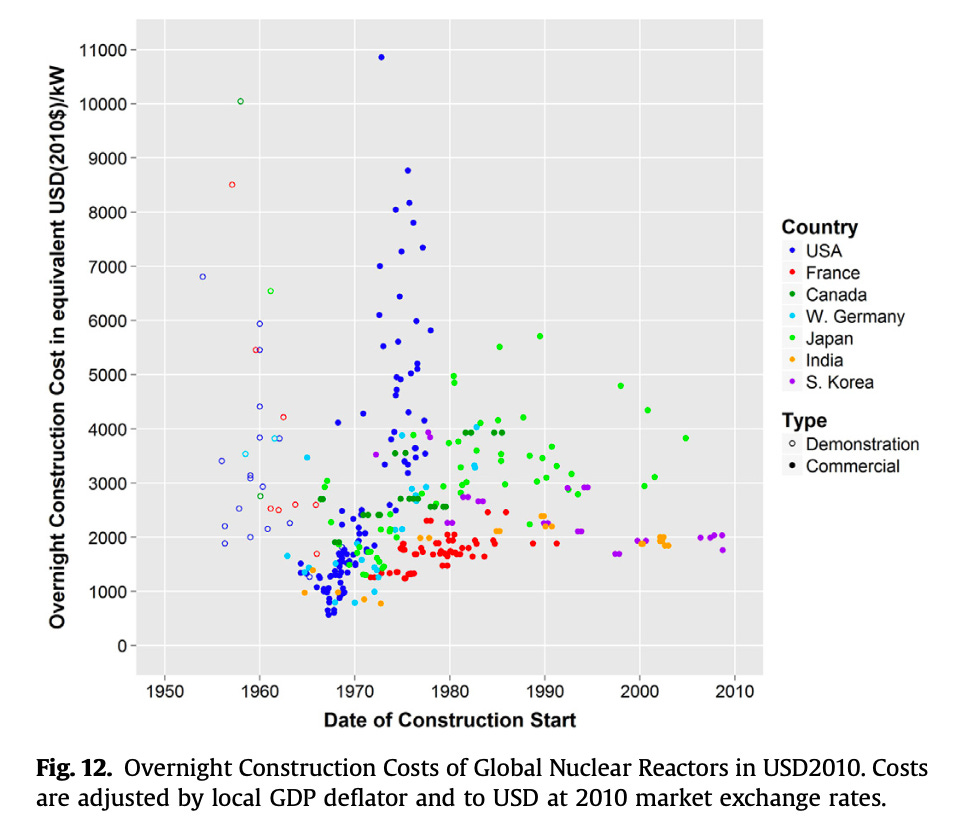

These are the construction costs of nuclear energy plants per country.

As you can see, they’ve remained fairly stable over the years for countries like France, India, or South Korea. For West Germany, they keep creeping up. And for the US, they were quite standard until around 1975. Then boom, they exploded. What happened?

Since the American Nuclear Regulatory Commission was created, they’ve approved a grand total of zero nuclear reactors. They also charge $300 per hour to review new projects. So maybe the NRC’s goal is not to approve nuclear reactors but to reject them.

We’ve decided as a society that the tangible benefits of nuclear, in the form of near-free energy, are not worth the perceived risks.

Why Do We Still Suffer from Diseases?

Right now, there are eight billion people alive. We could be monitoring their health, their pulse, their breathing, their sweating, their symptoms. We could compare that with their diseases, and realize quickly what causes most of them. Then, we could combine the treatments of every person on earth to see what works, what doesn’t, and what are the side-effects. Within a few years, we could train an AI that could prevent or treat any disease. Simply by sharing our healthcare data.

This is the task of humans today, but we don’t realize how impossible that task is:

Human doctors only see a few hundreds of patients a year, not a few billion.

They tend to see the same diseases, seldom rare ones.

They can’t read all the scientific papers published all the time.

They can barely follow their own discipline, forget about others.

They have human brains that do human processing on machine levels of data.

So why don’t we have AI diagnostics and treatments? For starters, health records.

Although the law says your health data is yours, healthcare providers frequently block your access. In parallel, are so concerned about healthcare data protection that this was one of the major reasons why they didn’t want to have zoom calls with patients or receive their emails before COVID.

I get why this world is so regulated. I really do. We need to protect the privacy of people who might have diseases that others shouldn’t know about. But current regulations overreach: We always look at their upside, never at their downside.

The downside of this secrecy, inability to freely manage your data, and bureaucracy in general is that tens of millions of people die every year of diseases we could eliminate if only all this data was much more easily accessible to medical diagnostics companies. We made a societal decision based on short-sightedness and costs without looking at the benefits. We didn’t realize the mountain of healthcare knowledge was not natural—it was built by billions of gnomes.

Thankfully, we’re making some progress in that direction. Last week, federal rules took effect forcing companies to give the power of their healthcare data to the patients. Soon, new companies will hopefully appear to take advantage of it, allowing every person’s data to contribute to medicine, allowing gnomes to build up the mountain of healthcare knowledge.

Back to Explore Mode

Explore-Exploit

You’re 24. You’ve been dating people since you were 20. Now you’re with somebody pretty good; the best you’ve met so far. But not exactly your dream partner. Should you marry?

Math has an answer for you. If you want to marry before you’re 35, no, you should not marry that partner. Why? This is the famous explore-exploit problem.

Who you choose as your partner depends on the quality of the pool: You want as good a partner as you can get. But you don’t know the quality of the pool! So before you choose somebody, you want to find out the value of the pool. This phase is called the “explore” phase.

Once you’ve established the baseline of what you can get in that pool, you want to go for as good a partner as you can attract. This is the “exploit” phase.

In the explore phase, you’re improving your learning. In the exploit phase, you’re using that learning, reaping the fruits of your work.

In this specific situation, it turns out that the mathematically optimal amount of time to dedicate to the “explore” phase is one third, and “exploit” should take two thirds. Since you want to marry by age 35, you have 15 years to find the ideal partner. One third of that (five years) should be spent calibrating the suitors. During that time, you should not commit to anybody and should keep meeting suitors instead. That’s the “explore” phase. But after that, starting at 25 years old, you should commit to whichever suitor is better than the ones you met before. That’s the “exploit” phase: You’re exploiting the knowledge you gained about the pool of suitor, now you know what a good suitor is, and you just need to find the best one. No more learning, just executing.

Civilization’s Explore-Exploit Problem

Today, society has decided that it’s not in the “explore” phase anymore: Whether it’s drone delivery, flying cars, energy too cheap to meter, diseases… We don’t want anybody to run any risk. We don’t want to learn. What we want is to take advantage of the learnings of billions of people before us, but we don’t feel comfortable doing the same for the billions coming after us.

We approved this without realizing what we were doing. Without realizing that every year we live today, we’re safer, but it comes at the cost of our own future and that of our children.

We left the explore mode sometime in the 20th century. We’re hindering our progress with needless rules. We should get back to it.

And yet many of the regulations we’ve enacted in the past are great. Environmental protection is important! Safety is important! How do we know which rules to eliminate?

The first set of rules to eliminate is that we should let people take the risks that only apply to them.

Let People Take Risks

The supplements industry is unregulated in the US. And it’s massive. You can buy anything that doesn’t claim direct health benefits.

But you can’t take any drug you want. For example, it’s very hard today to take drugs that are in research. But when people have terminal diseases, what sense does that policy make? Why wouldn’t we allow them to take all these drugs? Best case scenario, we find great cures. Worst case, they die and we all learn.

The difference between drugs and supplements is simply the health improvements claims. But maybe the regulation should not be “You are allowed to sell your drugs freely as long as they don’t claim a health benefit. If they do, they’ll undergo a massive process of approval”. Instead, maybe it should be: “The objective data supporting health claims needs to be extremely clear on any drug package”. What would be the role of the government in drug regulation then? Maybe:

If drugs have no evidence in favor or against them, there’s nothing to rule.

If they make a claim, it would need to be backed by evidence. Governments should codify this evidence to make it clear and simple to buyers what they’re buying.

If a substance is proven dangerous, they should ban it.

The same thing is true for human-challenge trials. We didn’t have them for COVID vaccines in 2020. Why? If somebody wants to willingly infect themselves to advance science, what sense does it make to prevent them from doing so?

Healthcare-data companies can’t improve their algorithms for lack of access to data. Why are we so aggressive about healthcare-data protection? Shouldn’t it be easier to anonymize and share healthcare data? Shouldn’t people be able to easily share their data with companies for research—with the right compensation? Why is that so hard?

Balance Social Risks Today with Technology Rewards Tomorrow

It’s slightly different when a risk is taken on behalf of others. For example, drone delivery: What happens with their noise? What happens if a drone falls on somebody and kills them?

But what happens if it doesn’t? If we play it so safe that we work for ages on improving drones in a lab instead of in the wild? Then we will never have drones, the same way as we wouldn’t have cars today.

There are plenty of regulations against drones that make it really hard for them to operate and learn. Should we have ways that these new technologies can quickly get approved for testing in different municipalities? Should the media pay so much attention to accidents when they happen?

Invest in Tomorrow

When we spend more on people’s retirement than their education, we’re not leaving the world better than we found it. We’re deciding as a society that the enjoyment of our elder years matters more than preparing our children’s future.

Here’s another example: Charles Jones, an economics professor at Stanford5, has found that high tax rates hinder innovation, because these rich people lose an incentive to innovate or might leave to innovate somewhere else. For instance, increasing the top marginal tax rate from 50% to 75% would raise 2.5% of GDP worth of tax income, but reduce innovation (and thus GDP) in the long run by 7%, hurting living standards overall.

If we want to improve the world of the future, we need to continue contributing to the edifice today.

Takeaways

The edifice of human knowledge was built by billions of forgotten people, each adding their little grain of sand, one idea at a time, one unlucky death at a time. We now enjoy that edifice’s penthouse and decided to stop adding to it. Sometimes for good reason, others because of short-sightedness, many times by fear.

As a society, we should stop being crippled by fear of what we can see, and start paying attention to the value of what we can’t. Progress takes failures. If we’re not OK with failures, we don’t make progress.

We’ve moved into exploit mode without realizing it. It’s time to get back to balance explore and exploit modes. It’s time to take more risks.

Clay Christensen’s The Innovator’s Dilemma explains it well.

Some are. Tesla and SpaceX, Apple, or Pixar are arguably the brainchildren of Elon Musk, Steve Jobs, and John Lasseter. But these are famous in large part because they’re exceptions, and because humans love their Great Man theories. In most cases, it truly is a massive team effort.

I’ll write about it in the future. I visited the Kitty Hawk company last year and it was fascinating.

I will write about this in the future, I promise!

Disclaimer: He was my macroeconomy professor in grad school.

While I am sympathetic to some of the points here, I would have to respectfully disagree.

The reason we don't have a lot of these things is not because of bureaucracy and heavy regulations. Or because of low tax rates.

1945 - 1971 was the golden age of capitalism and innovation and the top tax rate was as high as 91 percent.

Since we have steadily cut tax rates, especially for the wealthy, we've not gotten increased innovation. We have gotten increased hoarding. Which is not surprising because it's easier to make money from monopoly rents and stock buybacks than from productive innovation.

This is true even for the ostensible entrepreneurs who purportedly care only about changing the world, as evidenced by the fact that as they and their companies grow richer, they adopt the mindsets of the companies they replaced. People do risky things like try to change the world or an industry because it's usually their only option to make something of themselves and a legacy. When that is done to a degree, they revert to basic human laziness and caution, like us all.

And it's simply untrue that politicians and the public are excessively risk averse. In the noughties and early years of the last decade, silicon valley was championed everywhere. Indeed, several of these companies only got so big because the government didn't want to tamper with innovation.

It is only now after the dreams they promised have soured that people are now pushing back.

It's the same thing with self driving cars and medical data. The careless disrespect and disregard Uber had for the transportation industry and the manipulative ends to which Facebook used consumer data among many other examples is why people are so cautious.

They are cautious from experience and they have every right to be. Nothing in the last two decades has merited the reckless and manipulative optimism these companies have sold to us. Unless that changes, there is absolutely no reason for people's attitudes about promises of new 'innovation' to change as well.

I think a main thing that currently limits flying cars and delivery drones is the amount of noise they produce. We have flying cars, in common parlance they are called helicopters. And they are loud.

Think of how many neighbours you have within 100 metres of your house. What if even 1 in 10 starts using flying cars?

Maybe someone will invent a more quiet version. But you inherently have to move a large amount of air to stay up in the sky.

About that 1 breakdown in 100,000 km: an average car will cover that distance in about 7 years. It is not good if you have a fatal accident on average once in 7 years. Count me as one of the people who does not like this idea. That said, for our current generation flying cars this is solved by requiring that they can land using auto-rotation. The rotor is designed in a way that during a descent it somehow is still able to create enough lift to be able to pick a landing spot and survive the impact, even without power.

Incidentally, a well known but underexploited way to substantially improve our health is to actually start using bicycles instead of cars whenever it is feasible. We’re leaving a couple of years of extra life expectancy on the table right there.

It is always a balance. Tolerating the amount of people that get killed in traffic in the US is dumb. There are countries that get maybe 1/3d of that death toll per capita, and they have basically the same humans in the same cars as the US. But on the other hand I agree that we have to be honest with how safe or dangerous self-driving cars are. Should we compare them with the current situation on the road, or with the goal of zero fatalities? Maybe we should expect that self-driving cars become as safe as air travel (i.e. still much safer than travelling by road). Not sure what’s up with self-driving cars at the moment. I would have thought that we would have self-driving on motorways by now.