The Mental Pitfalls of COVID

Why Politicians Made the Errors they Made, and What that Tells Us About Ourselves and How to Prepare for the Future

Two weeks ago, I published the Top 25 Mistakes of COVID Mismanagement. But why were there so many mistakes? Why was the decision-making of governments so poor?

Thinking well is hard. We’re convinced we’re good at it, but humans are extremely biased1, we’re poorly trained in critical thinking, and we have few tools to help us think2. Between psychological biases and failures of reasoning, we end up making poor decisions. I will come back to this topic very frequently in my newsletter.

So let’s use the Coronavirus epidemic to identify the biggest mental pitfalls from which governments suffered during the pandemic, and learn from them to get better at thinking.

1. Not Doing a Cost-Benefit Analysis

Every single decision in your life is a cost-benefit analysis3.

What should I buy at the supermarket? Should I marry this person? Should I play with the kids or finish my work deliverable? Should I wash the dishes tonight or tomorrow? Should I lie in this conversation?

We don’t realize it because we do it mostly subconsciously. But here’s the problem with subconscious cost-benefit analyses: because we don’t make our assumptions or reasoning explicit,

We seldom question them.

It prevents others from challenging either our assumptions or reasoning.

At my job, when my teams are deciding what to work on, I ask them to make the reasoning in their proposals explicit:

What problem are you trying to solve?

What solution have you conceived?

How expensive is it?

What data do you have to support your confidence in the gravity of the problem, the efficiency of the solution, and its cost?

This is the type of debate you can have when you pull this out of people’s minds:

“How long is it going to take to build this?”

“A reasonable amount.”

“Ok but what’s a reasonable amount? A person.week? Two person.years4?”

“Oh no, probably something like the team of two engineers for six weeks.”

“That’s a full quarter worth of a person’s time. It’s a lot. Is there a way we can achieve the same goals with less time?”

Here, by making explicit the cost of a solution, it became clear that it was too much.

This isn’t rocket science. But in my experience, 99% of the time people don’t do it. Case in point, the COVID crisis.

In The Hammer and the Dance, I proposed to do the same:

This table shows potential measures that could be taken to stop the coronavirus, along with their benefit (R reduction), cost (in $), and confidence. It’s the exact same thing as a roadmap for my teams.

It’s entertaining to look at this table. It was never meant to tell people what measures to enact, but rather how to go about figuring them out. On one hand, oh how much have we learned since! On the other hand, this was clearly going in the right direction. Many of the very speculative measures suggested in the last column are still broadly valid today.

As we learned more during the pandemic, it became even clearer what decisions we needed to make, because many of the ones that worked best were also quite cheap: test-trace-isolate, border fences, masking, ventilation, and crowd limits.

Many papers carried out these analyses. Unfortunately, governments didn’t follow these steps. They got addicted to using Hammers, not realizing that they were extremely expensive and only justifiable if your goal was to completely stop the virus with cheaper measures later on. Or worse, some governments, like the US or Sweden, did very little at all.

Why didn’t they do the cost-benefit analysis? Because it wasn’t straightforward. How do you calculate the value of lives? The cost of closing a restaurant? The collateral damage of sick people avoiding hospitals for fear of contamination? How do you compare the closure of a restaurant to a reduction in privacy?

But you can actually make those comparisons. For example, whether we like it or not, lives have a price. Companies do this kind of thinking every day, for example in insurance. We do it as a society, too, by sacrificing lives for convenience when we limit speeds at 65 mph instead of 50, or when we allow alcohol sales.

The key to comparing two very different things is to put costs and benefits in the same units. Generally, money is a good unit to compare everything. If money is too hard, at least put some points instead.

Take this lesson away for yourself: Whenever you’re making a decision and you’re not sure how to proceed, write down the pros and cons and compare them. If you don’t know how to compare them, put a weight on each one of the things you value.

For example, you want to decide whether to travel to the beach or the mountain? Which house to buy? List the pros and cons (benefits and costs), rate them, put a weight on each factor, and compare them.

The point of doing these quick-and-dirty tables is not to take their results and run with them. Rather, it’s to allow you to process what really matters and what doesn’t, and also debate with yourself and others how to value each item. It’s very hard to have that conversation without an explicit cost-benefit analysis. But with this, you can this type of conversation:

“Oh, for you the comfort of House 2 is so close to that of House 1? I don’t agree. Did you see how neighbors could see through the windows? Did you hear the noise of the cars on the street?”

”I hadn’t thought about these. Let me reduce its grade from 7 to 5.”

Without a table like this, it’s very hard to have this type of conversation.

2. Not Accounting for Confidence

Every cost and every benefit has a confidence associated with it. Another word for the same thing is risk.

Let’s take masks. Their cost is quite clear: The money needed to buy them and the personal discomfort. They’re so cheap that the money isn’t a problem, especially compared to other measures. So there’s high confidence in a low cost5.

We had much less confidence in the benefits of masks. It looked like they could work: The intuition said they could work, mechanical analysis said they could work, all the countries that were successful in stopping COVID used them… But we weren’t sure.

Yet we didn’t need to be sure! If you have high confidence the cost is low, and the benefit might be high but you’re not sure, then you do it. What do you have to lose? Very little.

Compare that with vaccines.

The main benefit is protection against the virus, and the main cost is side effects. The financial cost is small enough that it doesn’t matter in comparison with the impact of the coronavirus on society.

But both costs and benefits have low confidence: Before testing vaccines, we don’t know how effective they are or what their side effects will be.

That means the cost-benefit is unacceptably risky for a new vaccine. That’s why we have trials before using them. In a situation of high costs and high benefits, you want to learn as much as possible, as fast as possible, to increase confidence in both.

That’s why I said we need challenge trials two weeks ago. The time necessary to increase confidence was calculated in months. Too much. A challenge trial is a small cost compared to that. By increasing confidence faster, we could learn the true value of each vaccine and quickly deploy those with the highest cost-benefit.

Last example: Long COVID. We still aren’t clear how bad it is. It looks like 50% of people hospitalized (that’s around 7% of all cases) have sequelae, and potentially many more. That is a society-threatening level of impact. With such a massive potential cost, even if confidence is low, you don’t want to gamble. That’s a crucial reason why a Hammer and Dance approach was superior to a Herd Immunity one.

3. Dogmatism

The opposite of cost-benefit analysis adjusted by risk is dogmatism.

When we say things like “I don’t want to wear masks because they’re against my individual freedom”, we’re saying: “There’s only one aspect of all costs, benefits and risks that matters: my personal cost of losing freedom by wearing a mask”.

Same thing with privacy when discussing contact tracing. Most of the conversation was around keeping everybody’s privacy, instead of comparing the true cost of privacy (getting movement data about a few people for a limited amount of time) against the benefits (stopping lockdowns).

It’s also true on the other side. Once lockdowns had been proven to work, governments decided to just keep using them, forgetting that the cost was huge and the true benefit was not in the immediate lives saved, but rather in keeping society completely free of the virus for months by replacing the Hammer with cheaper measures later on.

All these decisions are hard ones, with complex costs, benefits, and risks. When we only consider one cost or one benefit at the expense of the rest, and we don’t question that one cost/benefit, we’re being dogmatic, which is a sure way to end up wrong.

If you’re in a debate, try to notice when you focus on only one argument, or when the other side does the same with another argument. It’s a sure sign that one or both of you might be dogmatic.

4. Social Proof

If your friend jumps out the window, would you jump too?

As Cialdini explains in his books Influence and Pre-suasion6, one of the best ways to influence people is social proof: When you see other people doing something, you want to mimic it.

I was surprised to witness how much social proof applies to governments too. East Asian governments looked at each other, and they were broadly successful at controlling the virus. Australia and New Zealand, Western in culture but Eastern in location, were likely influenced by their neighbors too.

In the meantime, Western governments—especially European ones—looked at each other and broadly copied each other’s measures.

The first one—Italy—hesitated a lot. But once it had locked down the country, many other European countries followed.

This is the one silver lining of Sweden’s approach. It was catastrophic, but at least they should be admired for resisting the immense pressure of doing what every other EU country was doing, and doing what they thought was right instead (even if it was… very wrong).

If you’re making a decision and you notice that you’re taking into account somebody else’s experience, stop yourself. Realize you’re being swayed by social proof, and try to eliminate that bias. For example, you can look at stats to confirm whether your anecdotes are representative or not.

5. Availability Bias

If an example can come to you easily, you will take it much more into account for your decisions7.

Western governments could have used East Asian examples, but instead they just followed those of similar governments—I called this process “regionalism” in the past.

Availability bias, unfortunately, is much broader than that. You don’t just pay more attention to what’s closer to you. Also to what’s most recent or what’s more memorable: if cases go down we rejoice (even if they’re still too high), we declare victory when there’s few cases (even if we’re doing nothing to prevent upcoming ones), etc.

6. Authority

Another one of Cialdini’s favorite ways to influence: When authorities say something, we tend to agree with them: a police badge, a white doctor’s coat, a Nobel prize…

Sweden wasn’t affected by social proof, but it was affected by authority. Its politicians blindly followed the advice of their top epidemiologists, who turned out to be wrong.

The polarization that the US suffered is another example: Whatever politicians said, most followers did, questioning little, whether it was not wearing masks or vaccine hesitancy on the right, or outdoors activity bans on the left.

Don’t blindly follow the advice of experts just because they’re experts, or those in power just because they have power. Try to use your own judgment. If the decision is important, research it. If it’s too complex for you, seek the advice of more experts.

7. Escalation of Commitment & Confirmation Bias

How many countries do you know that changed dramatically their approach to the pandemic over the last year? I can’t think of any. The directions of the policies every country would follow for the entire pandemic were settled in March and April of 2020.

This illustrates Escalation of Commitment: when people start going down one path, they tend to continue going down that path. It’s intimately connected to Confirmation Bias—trying to find evidence that proves your position and ignore the evidence against it.

Compare that to the conversation that Oracle’s Larry Ellis had with Microsoft’s Bill Gates:

From my shallow experience, confirmation bias is the worst of all biases. It’s insidious because it’s the one that stops you from learning. How can you fight it?

We all have it, no matter what we do. You can’t avoid suffering from it. What you can do is catch yourself suffering from it and consciously challenge yourself. How do you catch yourself?

A big part is simply knowing it exists and that everybody has it. You will have it, many times, every day. So simply assume you’re always suffering from it. Now it’s easier: When somebody is providing arguments against your position, realize your mind is about to play tricks. It will try to find excuses to discount these arguments. Stop yourself and instead assume the arguments are right, and go from there.

Another way is to talk with your closest people about it, and to ask them to tell you when they think you have confirmation bias. They will tell you, usually when you both disagree, which will annoy you. But they will be right, since we all have confirmation bias. So take a breath and check your bias.

8. Reinventing the Wheel

“Good artists copy. Great artists steal.”—Pablo Picasso

Nearly everything has already been done. You are not original. Don’t try. The best you can do is draw inspiration from the best, and recombine them in your own unique way.

So why on earth would we wake up one morning in March, look at how Iran, Italy and South Korea had managed their outbreaks, and decide to go with Italy’s approach?

That might have been ok early on as we knew very little. But after that, it was clear which countries knew how to handle the pandemic, and which ones didn’t. At the top of the list were South Korea and Taiwan.

They’ve solved it. They know how to handle the pandemic. How on earth didn’t we just look at what they’ve done and copy it?

Don’t forget the lesson for yourself. Whatever problem you’re facing, somebody has faced it before you. Research what they’ve done, steal what you can, and adapt it to your needs. Don’t reinvent the wheel.

9. Desensitization (and hedonic adaptation, framing, storytelling, and anchoring)

“One death is a tragedy, a million deaths a statistic.”—Stalin

When the first COVID deaths started arriving, everybody sounded the alarm. As they grew, we were devastated. Each milestone a new failure: We have one Wuhan a day. One 9/11 a day. As many deaths as in WWII. As all combat deaths in the US’ history…

Every time a milestone was announced, we got desensitized. We still have two 9/11s worth of COVID deaths a week in the US. But it feels like we’re quickly leaving it behind.

Desensitization, and its nemesis, hedonic adaptation, tell us we get used to both good and bad things. For example, people prefer two 20-minute massages rather than a single 1h massage.

So how can you fight this effect? The right framing changes everything. With the right examples, the right emotion, the right facts, you can sway anybody. For example, you can use storytelling, anchoring, and pauses.

Storytelling: If we get used to the stat, let’s forget the stat and focus on the emotional experience. For example, NGOs are more successful raising money when they focus on the story of a single recipient of help rather than many. That’s also why the media always report crimes but seldom crime statistics. If they did, we’d realize crime has been going down for a long time.

Anchoring: It’s one of the most powerful negotiation tools. Humans don’t think abstractly. They tie any new piece of information to what they already know. So if you give them a number out of context, they don’t know how to assess it. That’s an opportunity to frame the number in their minds. For example, when I said “We still have two 9/11s worth of COVID deaths a week in the US”, that’s anchoring: I’m using 9/11 deaths as a comparison, because everybody considers those deaths as life-altering. It puts them in context.

Pauses: When a stimulus stops, the desensitization/hedonic adaptation resets. That’s why Europe felt the 2nd wave was much worse than in the US, even if the European Union’s 2nd wave was smaller than the US’.

It’s Not the Politicians’ Fault

If a handful of governments had failed, it would be easy to single them out.

Instead, the failure was widespread. Most Western governments failed to contain the virus.

When so many humans fail, they are not at fault. Politicians are humans. They’re flawed, biased, like you and me. Their failures are understandable.

What failed is the system. Systems should be designed to eliminate human failure. Here, they didn’t. Why have western democracies been so bad at incorporating information quickly? Why was decision-making so poor? Why were they so bad at coordinating citizens, which at the end of it is their sole function?

COVID is bad, but thankfully its Infection Fatality Rate is not civilization-threatening. Many upcoming challenges will threaten the collapse of our civilizations, from Global Warming to low fertility, Inequality or AI. If our governments have been exposed to be incapable of solving even COVID, what will they do about these more important problems?

Solving that is the ultimate goal of this blog. If you want to know more and help along the way, subscribe!

I’m sure I forgot cognitive biases. Which ones would you add?

This week, the premium subscribers-only article will go deeper in Geography Is the Chessboard of History. By looking deeper at a few regions like Spain, France, the Balkans and Germany, it further illustrates the points made in the original article. I also go deeper into some new geographic factors that determine History.

I will get back to this theme in two weeks. Then, we’re going to expand our analysis to the US, and from there to the rest of the world. If you want me to analyze new countries, let me know. I am planning on doing a special edition with a bunch more countries that people are interested in.

Before that, next week I’ll open a new topic: remote work. I like how these articles are turning out!

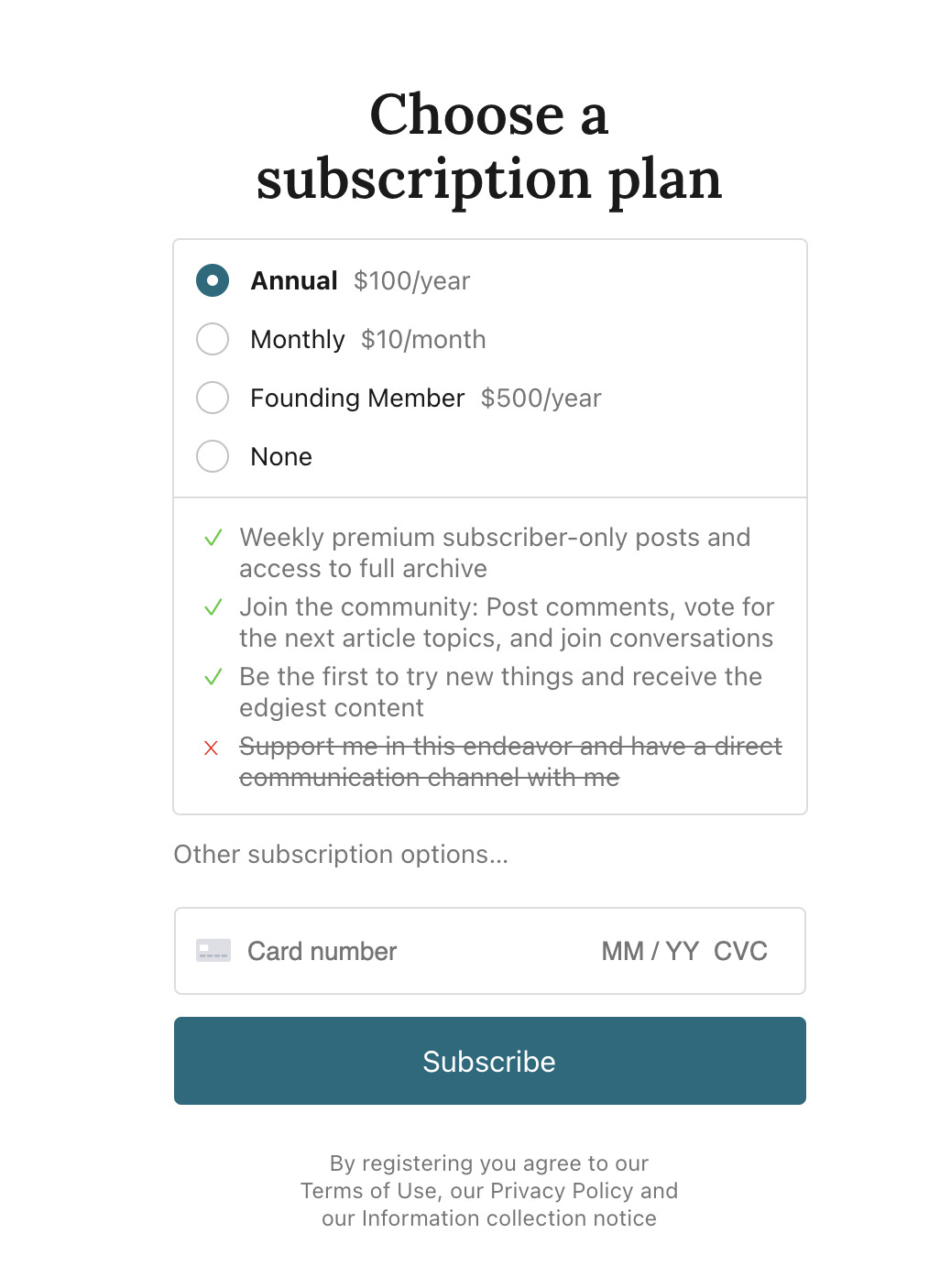

Some people ask me about the price of a subscription, so here it is. You’ll find it if you click on Subscribe.

If you want to supercharge your defense against biases, take that wikipedia page on cognitive biases and study it like it was a textbook in college. Go through the pages for each one of the biases and study them. I did it for my work as a product manager—I create online experiences for people, so I must know how they think and fail to think. It’s tedious, but it’s also a sure-proof way to learn everything you need to learn about biases.

One of my goals in life is to create a tool that can help humans think with others.

Or ROI (return on investment), if you prefer.

These are units. A person.week is a person working during a week. A person.year is a person working for a full year.

If you remember, early on the cost was much higher (the cost of opportunity, because there were so few), so there was all this debate about keeping them for healthcare professionals. Later on, the cost conversation of masks centered around another type of cost, personal discomfort. I believe that this cost is also low, since millions of people wear masks daily and don’t die from them. But others disagreed, and because this is less quantifiable, there’s less confidence that it is indeed a low cost.

If you want a primer on how to influence people, just read these books. They contain the 80-20 of what you need to learn. If you’re just going to read one, make it ‘Influence’. It’s a short and interesting read.

Or, as Wikipedia describes it, “The availability bias is a mental shortcut that relies on immediate examples that come to a given person's mind when evaluating a specific topic, concept, method or decision.”

From the notes: "One of my goals in life is to create a tool that can help humans think with others" - I am often thinking about something like that, especially in relation to the point related to the System: "Systems should be designed to eliminate human failure". I think currently we are facing the challenge related to the fact that we need to renovate our system: we have many vicious circles (like an algorithm feeding itself with wrong data) about many different topics (some things are going bad, because all the actors are doing what the system is pushing them to do, but sometimes we don't see the big picture and the consequences, sometimes we do, but we are not able to stop the circle). We need to redesign our system, but our system doesn't include a place for doing so: the possible places for doing so are affected by the system. It is time to start to think differently and the first step would be to find a space for doing so.

1932. «Franzosischer Witz» by Kurt Tucholsky (1890-1935):

«Der Krieg? Ich kann das nicht so schrecklich finden! Der Tod eines Menschen: das ist eine Katastrophe. Hunderttausend Tote: das ist eine Statistik!»