The Tree of Knowledge

How to Learn, Teach, Connect, Innovate, and Lead More Effectively

What’s the number one thing that holds us back?

What prevents many speakers from convincing their audiences?

Why is it hard to learn completely new disciplines?

Why are experts so bad at explaining things?

Why do students who fall behind have a very hard time catching up?

Why does radical innovation seldom work?

Why do old people have a hard time learning?

Why do people seldom change religions?

Why is confirmation bias the worst part of human psychology?

How can we learn faster?

Knowledge Is a Tree

Knowledge is like a tree. In the trunk, you have the core beliefs, the most basic ways you understand the world. Many of these things are even subconscious, such as the desire to survive, an understanding of gravity, or knowing that the sun will rise tomorrow morning.

From this trunk come branches, from branches come twigs, and from twigs come leaves. Each layer builds on the knowledge from the layers below.

For example, you might have a branch of personal finance, on top of which grow a few smaller branches: your savings management, your housing goals, your understanding of the economy…

Some twigs grow from the economics branch. For example, one about supply and demand, another one about currency, another one about GDP, and another about state intervention. Leaves then appear from these twigs, such as inflation or quantitative easing.

Every person has their own tree of knowledge and builds it up over time. It has some fundamental pieces of knowledge closer to the trunk, which branch out into more and more specialized knowledge, until they reach the leaves, at the limits of their knowledge.

This has a few consequences. The most obvious is that new knowledge always grows first as leaves. It’s always at the edge of what you know, and it’s flimsy when you first learn it. This is why, early on, when you’re learning something new, you’re not too sure about it.

But there’s much more.

Reinforcing Learning

The more you reinforce some piece of information, the stronger it becomes. It’s like adding more and more leaves to a twig. Each new successful leaf strengthens the twig, which strengthens the branch, which strengthens the trunk.

That’s why repetition is so important to learning. Why doing lots of exercises helps, why looking at a problem from dozens of points of view helps to reinforce your understanding.

One of the most successful and fastest-growing educational companies is Quizlet1, ranked number 233 for internet traffic out of all websites worldwide. They offer flashcards, which students upload to repeatedly revise questions and answers. This sort of rote memorization is useful, but it’s just highlighting the same leaf over and over again.

A better way to learn is to add a cluster of leaves, exploring slight variants on the same topic. By thinking about all these slight variations, you understand what drives the core concept. This is what engineers do in machine learning when they train algorithms with reinforcement learning.

Sheer repetition is so powerful that it can make a belief seem true, even if it isn’t. The mere exposure to a thought over and over again will make you think it’s true.

It’s one of the reasons why politicians and influencers try to make up anything that gets them on the news. The more their face is familiar, the more we like it, the more we trust it, and the more we think what they have to say is true. This is certainly the way Trump became elected against all odds.

This repetition effect is so strong that even correcting a fact can reinforce it! When you do that, you have to name that fact. And that fact repetition can dig it in. That’s why when Nixon said “I am not a crook”, people thought he was one.

Saying “crook” planted in people’s brains the image of Nixon referring to himself as a crook, and that mentally came before the denial of the statement. That reinforced the thought that he was, indeed, a crook. Even if he was just negating it. He should have learned from another Republican president and say instead “I’m the most trustworthy man in the world. Nobody’s more trustworthy than me! Trust me”

Connect New Knowledge

Can a leaf grow out of nowhere? No. It needs to be connected to a branch. The same is true for knowledge.

For example: how well do you understand this?

Although transaortic septal myectomy is the preferred method for septal reduction for obstructive hypertrophic cardiomyopathy (HCM), many centers and surgeons have little experience with the procedure due to reluctance of some clinicians to refer patients with HCM for operation. Indeed, concern regarding residual left ventricular outflow tract (LVOT) gradients and risk of iatrogenic ventricular septal defects has led many cardiologists to use alcohol septal ablation as first line therapy for obstructive HCM refractory to medical therapy.—Transaortic Septal Myectomy for Obstructive Hypertrophic Cardiomyopathy, Anita Nguyen, MBBS and Hartzell V. Schaff, MD.

Odds are you didn’t understand a thing. That’s because most of us know nearly nothing about this topic, so when we are faced with new pieces of knowledge, new leaves, there’s no branch to connect them to, and the leaves fall to the ground. We are missing a complete branch system on cardiology and surgery to make sense of this information.

Falling Behind

This is one reason why it’s disastrous when a student falls behind. It means they were not able to incorporate new leaves into their branch system. The further the class moves ahead, the bigger the distance between the student’s branch system and the new leaves. Eventually, there comes a point when the new leaves all fall to the ground because the student can’t figure out how to connect them at all.

At that point, the student disengages completely and questions whether their inability to learn is their fault (“I’m dumb, that’s why I can’t make sense of this”). This is such an uncomfortable feeling that the student will try to avoid it by thinking about something else. Sometimes, their self-image of failure will be unacceptable, so they will create an alternative identity they can hang on to. For example, think of the rebel who decides they don’t want to engage in class.

If this is true, the way to help students who fall behind requires two interventions: one about knowledge, and one about identity.

Their more basic knowledge is too flimsy. They need to reinforce it. So they must go back, identify all their knowledge holes, and rebuild and reinforce them.

Their identity must be shifted again. They must believe that they’re good at learning. Their learning must be celebrated, and their identity as learners must be celebrated.

The celebration should not be about them knowing, but about them learning. If you celebrate somebody knowing something, they will build an identity about knowing things, and it will be harder to prove them wrong. But if instead you praise their learning ability and effort, they will develop a growth mindset.

Crisscrossing

“Inosculation” is a term that you’ve probably never heard before. It’s a completely new leaf that is quite scary. So let’s connect it further to your existing knowledge tree branches: inosculation is when trees or branches merge together.

Tree branches connect to other branches of the same tree. Sometimes, they can even connect to branches of other trees. Even trunks can connect to those of other trees.

Inosculus comes from osculatus, which means “kiss” in Latin, from “os” (mouth) and “culus” (like a diminutive), which means “little mouth”. It's close to “inoculate”—which is also about mixing organisms—but it adds an “s”. Inosculation.

Why am I telling you this? To illustrate how hard it is to add a completely new leaf to your knowledge tree. Do you think you will remember the term inosculation? Probably not. But the more I talk about it, and the more aspects of it I explore, the more likely you are to remember it. I am connecting the leaf of inosculation to as many branches as possible. I am inosculating inosculation2.

This is the point of inosculation: branches and twigs don’t just branch out indefinitely. They also connect to each other. Knowledge is even more interconnected. Inflation is not just connected to economics and personal finance. It might also be connected to your relationship with the bank, with your loss of purchasing power, with the decision to buy a house, with the hardships of paying a mortgage, with the tensions you might have with your partner because of it…

You don’t develop your knowledge tree only by adding leaves. The more these leaves are connected to different twigs, the more these twigs are connected to branches, the more all of these are connected to each other and to the rest of the tree, the sturdier they will all be, the better you will understand the new concept, and the more you’ll be able to build new concepts on top of it.

Sclerosis

It looks like kids’ knowledge grows super fast, like a young tree.

Compare it to the growth of an older tree.

Trees go from a seed to a small tree within weeks. Impressive. As they grow, however, their growth rate slows down. You can’t double your size every few weeks forever. The older they are, the slower they grow, until they don’t grow at all. They remain fixed in time. Nothing changes.

Knowledge is like that. It grows super fast early on. The bigger its branch structure, the more information it can absorb. But at some point, the structure is too complex, too stiff, too sclerotic, too ankylosed. It doesn’t allow for new data, new learning.

“Science progresses one funeral at a time.”—Max Planck.

It doesn’t need to be this way.

Exponential Growth

Some trees, like Giant Redwoods, grow their height for decades, even hundreds of years.

The same is true for knowledge. An old person will not grow his knowledge on a relative basis as fast as a young person. He can’t double his knowledge every year. But he can add as much knowledge on an absolute basis: with all his knowledge branch structure, it’s much easier to add information to the fringes, if only he makes the effort.

Not only that. What the older tree does is add a much greater volume of branches and leaves, much faster.

General Sherman Tree (in the Giant Forest) - widely considered to be the world's largest tree - may also be the fastest growing. They found that the diameter of the tree had increased about three inches during the forty years years since careful measurements were made in 1931. Three inches of diameter in forty years may not sound like rapid growth until one remembers that the General Sherman Tree is 272 feet high and more than thirty feet in diameter - well over one hundred feet in circumference. Layers of new wood one millimeter thick spread over a surface this broad and this high, means that during the last forty years the General Sherman Tree has added enough new wood each year to construct a five or six room house. Source.

An old tree might not add much height, but it adds volume, and it strengthens the existing trunk and branches every year, adding one ring after another. Just like giant sequoias, older people can add new knowledge across lots of disciplines they are already familiar with, and every time they do, they strengthen what they already know.

Learning something completely new is harder for an old person than a young one, but not as much as people think. Old people are just not used to learning completely new things anymore, and that’s what makes them uncomfortable. The loss of the habit.

That’s for your own knowledge. Now what happens when you’re talking with another person?

The Wars of Knowledge Trees

Your tree is unique. Some branches might look similar to those of another person, but nobody has the exact same branch structure and leaves as anybody else.

When two people talk, they come at the conversation from their very different trees. It’s a miracle we can understand each other at all. But in many cases, that is just an illusion. As we talk, we build new leaves in our tree, the other person builds their own leaves, and we *think* they’re the same, but not quite. Even when they look alike, they are connected to a vastly different tree. This creates many different barriers to communication.

Connecting Trees

What would happen if Marie Curie met Kim Kardashian?

The professions of these two amazing women are based in two completely different branch systems: Physics for Marie, Social Media Influence for Kim. Not only that, but each one of them has spent much of their time at the cutting-edge of their field, building new leaves all the time, taking for granted the more basic parts of their discipline.

KIM KARDASHIAN: You can’t believe how much dough we made through our mobile game when we funneled customers from our Insta.

MARIE CURIE: Dough? Mobile? Funneled? Insta?

KIM: Oh yeah, I forgot. So we published this game on mobile and…

MARIE: What’s a mobile?

KIM: Right. So now phones are mobile. You can walk around with them and they work.

MARIE: Wow! And you play games with them?

KIM: Yes. I have my own character and…

MARIE: What do you mean? Do you speak on the phone to everybody who wants to play?

KIM: Ok, Marie. Tell me about radioactivity.

If one tried to explain their branch system to the other, she wouldn’t know where to start:

There’s an entire branch system to build. So much work!

The way the expert learned that system is probably not the best way to teach it. The expert must craft a learning experience different from the one she went through.

And she needs to do that while perhaps having lost empathy for the newbie, since they haven’t been in their shoes for ages.

The rest of the tree is different for the expert and the newbie. How is the expert meant to connect a new discipline to an existing branch structure if they don’t even know the existing branch structure of the newbie?

That’s why teaching is so hard. Most people come at it from their own experience, their own tree structure, and try to explain that. You can’t do that. You must start from the branch structure of the other person.

That’s why all communication disciplines tell you to start by understanding your audience. You need to figure out the structure of their knowledge tree first. Then, you craft a message that resonates with that tree, that the audience can easily connect to their existing branches. And from there you can build up the entire new knowledge structure, branch by branch, leaf by leaf.

Relationships: Empathy

You know how much people say you should listen before talking? That’s what it means, really. If you talk before listening, you push your ideas without understanding how they will land on the other person. You can’t have empathy.

If instead you listen to others, you can adapt to their needs. That’s why people love it when others listen. They appreciate that the other person is making an effort to recreate their knowledge structure. From there, they will be better positioned to help.

Relationships: Talking Past Each Other

Another problem happens when two people have different branch systems about the same topic.

Because they’re on the same topic, they have some branches and leaves that are similar, but many aren’t. And the way they’re connected doesn’t make sense to the other person. So what usually happens is that these two people talk past each other:

“No you don’t understand, you should think about it this way!”

“No, this way!”

The way to solve this is the same: to jump off into the other person’s branch system, and build it for yourself. And little by little, you will connect that person’s branch system inside of yours.

If it makes sense and it all connects, perfect! You just enhanced your branch system!

If it doesn’t, you’re now in a position to point out the other person’s weaknesses in their branch system. And THAT they will listen to. Because they know their system, if they want to improve they usually realize the incoherence.

Now they’re open to listening to your take on the problem. And because you have now worked within their system, you are acquainted with theirs and yours, you know where each one is strongest, and you can rearchitect them. And you can do it in a way that is comprehensible to the other party, because you can start with what’s right about the other person’s tree structure, and build up from that.

Innovation vs. Familiarity

Something similar happens with innovation. As reader Rob Hoeijmakers reminded me, the famous 20th century designer Raymond Loewy—behind designs such as the logos of Shell, Exxon, TWA and BP, the Greyhound Scenicruiser bus, Coca-Cola bottles, the Lucky Strike package, Coldspot refrigerators, the Studebaker Avanti and Champion, and the Air Force One livery—introduced the theory of MAYA: Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.

But Loewy felt that his sensitivity to the familiarities of his consumers connected to a deeper layer of psychology. His MAYA theory—Most Advanced Yet Acceptable—spoke to the tension between people’s interest in being surprised and feeling comforted. “The consumer is influenced in his choice of styling by two opposing factors: (a) attraction to the new and (b) resistance to the unfamiliar,” he wrote. “When resistance to the unfamiliar reaches the threshold of a shock-zone and resistance to buying sets in, the design in question has reached its MAYA stage: Most Advanced Yet Acceptable.'—Hit Makers, Derek Thompson

With the right balance, people will be able to recognize the innovation, put it in context, tie it back to their knowledge tree, and then build the new knowledge structure on top of it to recognize the innovative part.

Think about the first years of the Internet or Blockchain. Most people didn’t know what to do with them. These innovations were too new, so it took decades for people to understand their potential and fully exploit them.

Meanwhile, a Tesla car or a SpaceX rocket are familiar enough that people can understand exactly what their innovations are.

Remember that when you innovate: figure out what you should reuse, what wheels you shouldn’t reinvent, and focus the innovation on a few specific parts.

Leadership: Pacing and Leading

Why can’t people agree on religion and politics? Because their knowledge structure is fundamentally different. Each side is focused on replicating their own knowledge structure in the other person’s brain.

A much better way to influence others is to understand them first, to see things from their side, and then bring them back to yours from there.

Successful leaders know this. That’s why they follow a tactic called pacing and leading:

“Pacing builds trust because people see you as being the same as them. After pacing, a persuader can then lead, and the subject will be comfortable following.”

Scott Adams, Win Bigly

Only Nixon could go to China. It was easy to convince Democrats that meeting with China was a good idea. It was hardline conservatives who opposed it, so it was them that Nixon had to convince. By showing that he hated commies, he paced them: he was on their side and thought like them. Republicans could rest assured that, whatever Nixon would do, he wouldn’t be soft on communism. So when he went to China, when he led the Republicans into establishing relations with China, it was acceptable to them. Only Nixon could go to China.

Trump did very much the same thing with Republicans. That’s what his followers meant when they said “he says it like it is”. He’s one of us. He thinks like us. He is not scared of that. Therefore he must have our back. And once he paced Republicans, he could lead them into… uncharted territories.

Pacing shows that you mirror people’s knowledge tree. You are like them. That makes it so much easier to then lead them.

Relating: the Inefficiency of Meeting New People

You’re at a party. There’s a person that looks interesting. You want to meet her. But what do you say?

YOU: Hi! Did you see how cold it was today?

HER: Hi! Yeah, onion strategy!

YOU: Always bring your layers!

HER: …

YOU: …

YOU: So, what do you do?

HER: I’m an accountant.

YOU: ...

HER: Hummm… What about you?

YOU: A project manager.

HER: …

YOU: …

YOU: So, what hobbies do you have?

HER: I hike and I hang out with my friends. What about you?

YOU: Hm I like videogames and painting.

YOU: Anyway, let me get a drink for my friend Lindsay.

HER: YOU KNOW LINDSAY?!

You: Yeah, I’m Lindsay’s best friend from college.

YOU: NO WAY!! I’m Lindsay’s best friend at work!!

HER: NO WAY!

Why is meeting somebody new so nerve-wracking? Because the mental work you’re doing is extremely hard.

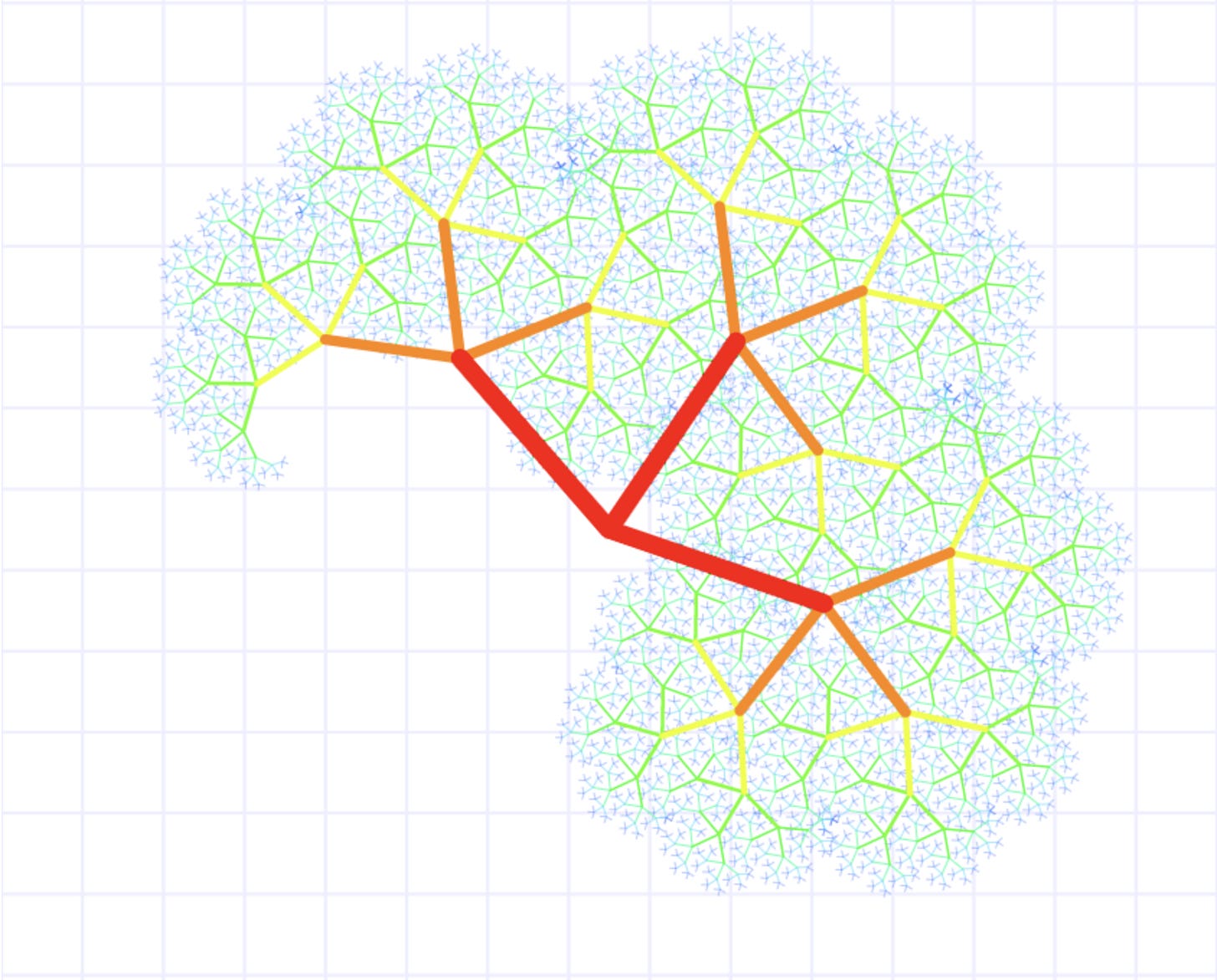

Imagine this is your tree of knowledge, with your areas of interest in darker blue.

Your interlocutor and you have no idea about each other’s trees, and your goal is to find in as few seconds as possible an area of both of your trees that is very interesting to both of you. How are you supposed to do that?

You’re going to make guesses based on what’s most commonly known and interesting to other people.

So you will start talking about topics that might not be very interesting to either—but which you know people tend to be interested in, at least a bit. Or you might even talk about something you’re not interested in at all, simply because others tend to be somewhat interested in that. Hence talking about the weather.

But this is the knowledge and interest map of the other person:

You should be talking about Lindsay immediately, but you don’t, because it’s not a typical interest. Instead, you will be frantically exploring the more common interests people have, wasting both of your times.

If you had a map of the other person’s knowledge tree, colored by interest, you could easily figure out what to talk about. But we don’t carry our colored knowledge trees around, so we’re forced to use the highly inefficient, sequential system of talking to touch on lots of topics until we find something mutually interesting. Naturally, you start from the pieces of people’s life that take most of their time and interest: work, family, hobbies… But it’s still inefficient.

I came to this realization when I was having dinner with the Presidents of Greece and Austria. We were a dozen people in a small, cozy restaurant in the Austrian Alps, but I didn’t know anybody else. Obviously, thousands of people try to talk with country presidents, so their tolerance and interest for engaging with new people must be extremely low. So when I started talking with them, I felt like I was trying to figure out as fast as possible what topics we could both relate to, which was doubly hard because as presidents they can’t say what they think, which makes their conversation bland…

Needless to say, it didn’t go too far, which I found it to be a pity, because of course these people must be interesting! And I want to believe I might have something interesting to share with them. But the inefficient process of sequentially exploring topics we might be interested in didn’t get us to find these topics in a reasonable amount of time.

This happens all the time when people are trying to find a couple, for example. That’s one reason why scientists developed 36 questions to fall in love, so the process of getting to know each other could be as efficient as possible to create intimacy. Maybe I should have tried those questions with the presidents...

Takeaways

Let’s summarize:

Knowledge is built up through layers. You need more basic knowledge before you can access more advanced knowledge.

You can’t learn things that are too far removed from your knowledge tree.

If somebody doesn’t understand something, it usually means they’re lacking some other knowledge, not just the thing they’re trying to learn at that point.

The best way to learn something is to connect it to something you already know.

Ideally, not just one thing, but many. The more disciplines you connect something to, the more branches you will build across, and the stronger your new knowledge.

You need to repeat something over and over to learn it well.

Even better, explore different aspects of it.

Anybody can learn very fast. It’s not just kids.

Most misunderstandings come from the fact that your tree is different from other people’s trees.

The best way to teach other people, or to debate with them, or to help them, is to recreate their tree inside yours. You do that by listening and asking questions. Then you can build your additional knowledge structure on top of theirs in their mind.

When communicating, as well as when innovating, make sure you always remain familiar.

Before you lead, you must pace.

Meeting new people is a race to find the most interesting overlap areas between your knowledge trees as fast as possible.

Now, do you remember that word meaning branches or trees coming together?

Today we’ve covered why your knowledge is like a tree and how you can use this metaphor to improve your interactions with others. In the paid article this week, we will cover something even more important: How do you change somebody’s existing beliefs, somebody’s knowledge tree? How do you change yours, which is probably your biggest obstacle to personal growth?What happens when the tree you’ve built is wrong? How can you learn from a mistaken foundation? Subscribe to read it.

As of October 2021

Very meta.

Thank you for listening to the feedback of those of us who are avid readers and "get" visual charts & graphics, but have a much harder time with audio only presentations and, particularly, the back and forth of a podcast. You have an amazing gift for communicating in a style we reading/visual folks can really sink our teeth into. Just because podcasts are "in" right now does not mean we will simply move over to that format. Our brains don't work nearly as well to absorb information delivered solely via audio, so we will 'tune out', thereby missing out on all the amazing insights and perspective you have to share.

Excellent summary! If I may add anything, I would try to make a distinction between facts and opinions. Our knowledge relies on both. Ideally, we should filter out opinions (or confirm them as facts if possible) to strengthen our knowledge tree. Not everybody goes in depth, pursuing a reality check on everything, or even question the information they are fed with. Lately, the line between fact and opinion is even more blurred by the unmanageable amount of information that we are daily bombarded with... people are tired and unwilling to get to the bottom of things and the confirmation bias conveniently fills the gap that would otherwise lead us to cognitive dissonance (we unconsciously tend to avoid it altogether). We want clear and consistent information. We need to take decisions based on that information. The bias creeps in to give us some reassurance and spare us of uncomfortably changing course when new data conflicts our old beliefs. Here is the point: our knowledge tree can be strengthened into a fact-based ground or into a shaky, biased, opinion-based soil. Communication is nearly impossible without a common understanding of the facts. Even if you travel back someone's twigs and branches to understand his thought process and values, you may have to literally dig to the roots for the ground truth. If, beyond the roots, you find a shaky soil of unverifiable beliefs, you may never be able to communicate efficiently with that person. Sadly, many of us are already there. We take sides and entrench ourselves without leaving space for new branches to reach out into different realms, we even prune the twigs that go into uncomfortable topics contradicting our old trunk's principles.

Further questions:

How do we change people's minds when they refuse to acknowledge reality and learn? This is a heavy burden and education plays a fundamental role (but we have to update our education system first). Who will change the education system? For sure, not those who don't understand the problems. Who is in charge? How do we get in charge people that are willing and able to make the change? What is the critical mass in our leadership that would flip the switch to the right position? How much time we have until things go worse (hope not as bad as "unrecoverable"...) and how do we get there? I do not have good answers, but please keep bringing up the problems that you see so people can read and learn. Not yet enough people (far below the critical mass) with high visibility to get traction at larger scale, but all transformation must start somewhere, even from a small seed... or a few.

Thank you!