What NFTs Can Learn from Art and Luxury

And if you don’t understand NFTs yet, read this.

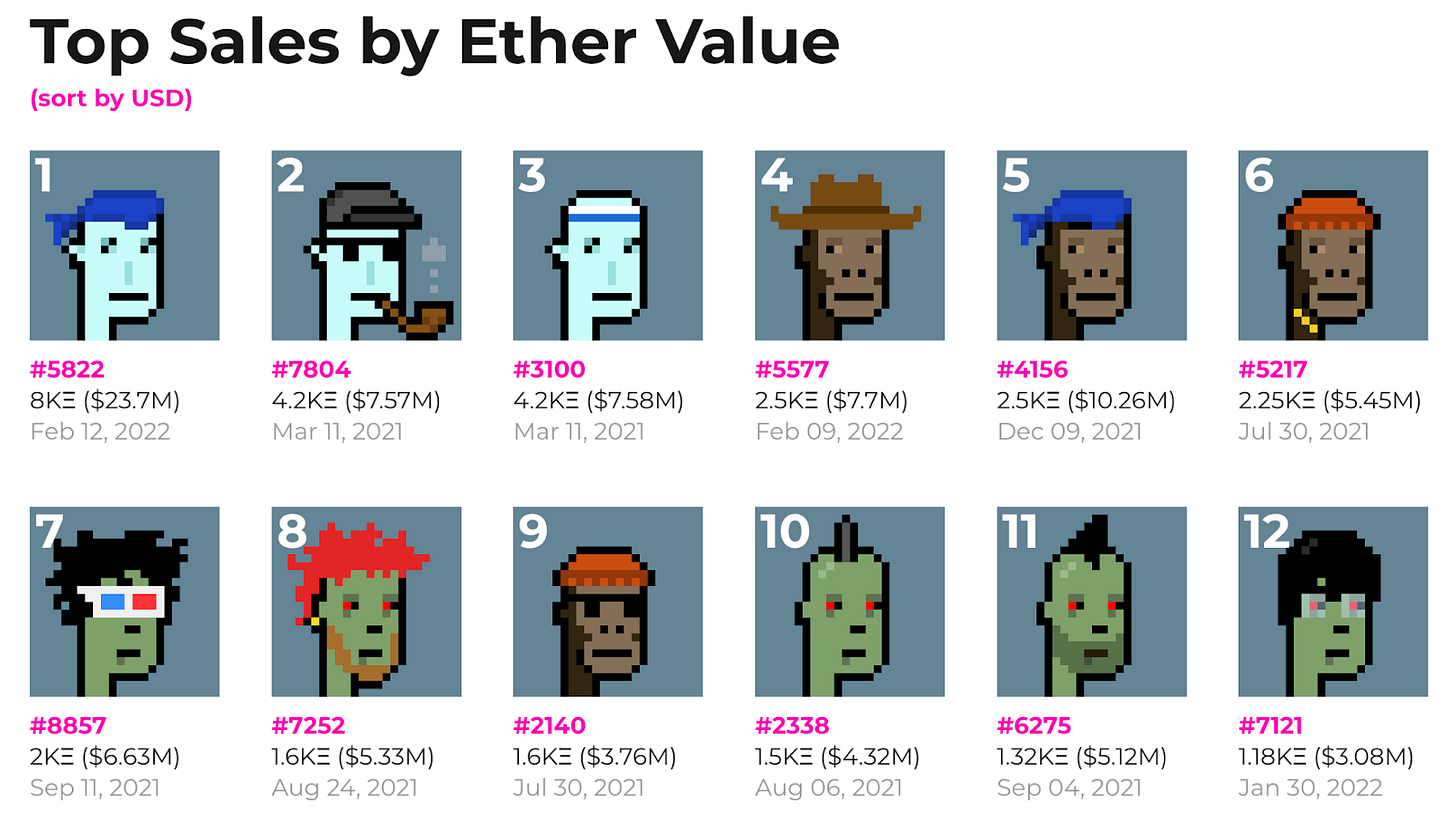

Digital images of apes have sold at over $3M a piece.

Famous people rushed to get one.

A pixelated jpeg sold for over $20M.

20-second NBA highlights sold for up to $230k. The image below, Everydays: the First 5000 Days, sold for $70M, the sixth most expensive artwork sold by any artist alive.

But over the past few months, the volume of NFT sales1 has been going down.

A tweet from Jack Dorsey—a Twitter founder—that sold for nearly $3M last year, only received bids below $300 when it got listed again.

It’s confusing. Is this market going up or down? Why have some NFTs reaching crazy prices? Is this a fad? Why was there a $40B market for them in 2021? Why are digital goods selling for more than their physical counterparts?

The reason why this is counterintuitive for most people is because what normally drives the price of things is scarcity. There’s only so much gold or wheat in the world. Only so many Picassos. So many Gucci bags. But many people want all these things. Less supply than demand means people compete for the same resources, which drives prices up.

This is not supposed to apply to digital goods. They can be copied infinitely for close to nothing (yes, even the images corresponding to NFTs2). So why are NFTs valuable? Will they move beyond jpegs into other parts of digital life? What do the makers of NFTs need to know to keep them growing?

The answer is this: NFTs are valuable for the same reason that luxury goods and art are.

The Luxury in Luxury

Think of some luxury item, like a Ferrari car, a Fendi bag, a giant mansion, a huge diamond ring, a Van Gogh, or a private concert with Beyoncé. What makes it luxurious?

It’s expensive?

Exclusive?

Exquisitely crafted?

Famous?

Traditional?

Useful and sturdy?

But which of these matter, and why?

The Value of Luxury Bags

What are you buying when you purchase a Gucci bag worth $3.4k?

First, there’s a utility value: you carry things with it.

But you could carry more things with a plastic bag.

Since a plastic bag probably costs less than $0.01, that is not what you’re buying when you pay $3,400 for a Gucci bag. That bag is functionally useless. So what is it then?

“If China can make the same goods, to the same standards, and at a fraction of the price, isn’t buying the cheaper unofficial version what any rational shopper should do?”—Alice Sherwood, The Guardian.

A second component is durability. A Gucci bag is arguably well built. It’s timeless. But 100 plastic bags are likely to last you longer with more utility than your Gucci bag. So durability can’t be it either.

The craftsmanship of a well-designed bag is also an argument that buyers of expensive bags will put forward. But it’s possible to have really good counterfeited bags sold for dimes on the dollar. If you can hardly tell the difference between the real thing and the copy, why would you buy the real thing? Yet people still buy the real thing. That means those spending $3.4k for a handbag are not doing it for the well-crafted physical asset.

“When you buy a brand, you’re investing in the dream. You know Beats who were bought by Apple? They make headphones that are good, but not amazing. People buy them for cool. You are buying quality, but you are also buying being part of a group. The designers aim to make a nice product with a nice dream. You buy it and your self-esteem will be good.”—Bjorn Grootswagers, regional director of the anti-counterfeiting organization React.

Let’s look at it from a different angle. What’s the worst nightmare of the owner of a counterfeit bag?

To be called out on the fakeness: “You bought a Gucci bag imitation? Why, you couldn’t afford the bag, but you still wanted to look cool? How pathetic!”

So the function of spending these $3.4k is social. You’re buying the bag for status, of course. So what are the components of that status?

What would happen if several homeless people were carrying Hermès bags? It would immediately devalue it. Why? Because what you’re buying is exclusivity. Only a few people can buy the bag, which makes you, the owner of this amazing and unique bag, special.

What is it about that exclusivity? For starters, owning a $3.4k bag signals wealth. Not everybody can spend that kind of money on something so functionally useless. You must have a lot of money to do it. Buying that bag is like saying: “I belong to the group of people who can spend $3.4k on something worthless and not go broke.” That’s what exclusivity means. It means that you define yourself by those you exclude. Buying a Gucci is like taking a pile of cash and burning it for all to see that you belong to the group of those who can afford it.

And why would you want to signal wealth? Because it puts you higher in the social hierarchy, which gives you all sorts of evolutionary advantages.

The Evolutionary Value of Economic Status

With more wealth, you can afford more things: more food, more help, better shelter… A person with such wealth will attract people from the other sex, because their children will have more resources and thus a higher likelihood of surviving. So wealth gives you a reproductive advantage, and you’re justified in showing it off.

It also attracts more allies, because they assume there’s more wealth where that comes from, which means more opportunities for them. So wealth attracts supporters. That means more power, which also translates to reproductive advantages.

“While ecological selection (the pressure to survive) abhors waste, sexual selection often favors it. The logic is that we prefer mates who can afford to waste time, energy, and other resources. What’s valuable isn’t the waste itself, but what the waste says about the survival surplus—health, wealth, energy levels, and so forth—of a potential mate.”—Robin Hanson and Kevin Simler, The Elephant in the Brain3.

This is a male bowerbird’s bower. How functional do you think it is to build this weird little monument? Why gather all these blue scraps? None of this is functional. They do it to show they have time to waste—which means they can spare time, a key source of wealth. For example, why are all these scraps blue? Because blue was extremely scarce in nature before plastic, so bowerbirds evolved to appreciate when a male could find a lot of blue things. It meant it was so fit that it could waste all its time finding blue stuff. None of it is used after the mating. Image source.

A guy does the same thing when he buys a big rock and puts it on a ring to propose to his girlfriend. That rock has no use. Beauty is not it, because zircons can be shinier, artificial diamonds are more perfect, and both of these are cheaper. The point of a big natural diamond is to implicitly say: “Look, I can burn $10k on a diamond because I’m so rich.” And that’s why rings with small stones are uncomfortable to wear socially.

“Someone asked me outright if it was a real engagement ring. Other people asked the same question with their facial expressions, rather than words.”—My Engagement Ring Made People Uncomfortable, Ema Hegberg.

OK, so we want to show off our wealth by spending it on things that are expensive. But then why don’t we show off by simply burning cash outright?

Flaunting

People don’t burn cash in piles. It’s a douche move. But why? Because it’s flaunting wealth.

Did you hear about the I Am Rich iPhone app?

Have you ever seen a nightclub bottle parade?

A group of scantily dressed girls carrying alcohol bottles with sparklers. Why? WHY?!

They’re telling everybody: “Please notice how these people just spent a ton of money on these bottles just so you can see how much money they’ve spent.”

How do others usually react? Some will be attracted by the wealth display. Others will be jealous because it makes them feel inferior. Yet a few others might deride them—another way to psychologically deal with the affront of being belittled.

When people flaunt their status, they make the statement that their social status is superior to yours. People are either attracted to the wealth or repelled by the flaunting.

This is the art of luxury: you’re trying to show wealth without flaunting. Show wealth without being obvious about it.

Many people will criticize somebody for carrying a Chanel bag, but that sounds less likely to me than the club bottles. The bag is still visible, but it’s much less in your face, more inconspicuous. Why? What’s the difference between a luxury bag and a nightclub bottle?

The owner of the bag has the plausible deniability that they bought it because it’s high quality: “Look at the craftsmanship. How carefully it was designed. How masterfully executed.” You don’t have plausible deniability when you’re burning cash or buying bottles at the club.

That’s the function of the good materials and finish of the bag. It’s the excuse that you’re buying the luxury good for its qualities instead of for its price.

Plausible Deniability

So when you’re buying luxury, you’re buying two things at once: something exclusive (because of its scarcity) and plausible deniability (to avoid flaunting).

A $10k diamond ring excludes all those who can’t afford it, but “the size of the stone tells me how much my fiancé loves me.” Plausible deniability: “Two months worth of salary. It’s the appropriate amount for a wedding ring, right?4” “And we all know a diamond lasts forever.5”

A person who pays for backstage access to an artist will take a selfie with them (exclusivity because of scarcity), but they do it “because I love this artist” (plausible deniability).

A Gucci bag is expensive (so, exclusive) but “well crafted, look at how well sewn it is!” (plausible deniability).

Gold is valuable because it’s scarce, but the plausible deniability comes from its properties: “It doesn’t oxidate! It’s malleable! It has industrial uses!6”

A Ferrari is very expensive, but it also has plausible deniability: “I love cars, and their XFGK engine is amazing. And it’s been my dream since I was a child.7”

Summarizing:

Luxury items are not bought for their functional properties.

They are bought primarily as a way to show off the money spent on them.

But that money must be spent without flaunting.

That’s the function of plausible deniability: excuses that can pass for valid reasons for the purchase, so that it doesn’t feel like flaunting.

This leaves a key question: what brings good plausible deniability? We can find the response in art.

Evolutionary Art

In The Elephant in the Brain, Robin Hanson argues that art has intrinsic and extrinsic properties:

Intrinsic properties are the qualities that reside “in” the artwork itself, those that a consumer can directly perceive when experiencing a work of art. They include for example everything visible on the canvas: the colors, textures, brush strokes, and so forth.

Extrinsic properties, in contrast, are factors that reside outside of the artwork, those that the consumer can’t perceive directly from the art itself. These properties include who the artist is, which techniques were used, how many hours it took, how “original” it is, how expensive the materials were, and so on. When observing a painting, for example, consumers might care about whether the artist copied the painting from a photograph. This is an extrinsic property insofar as it doesn’t influence our perceptual experience of the painting.

The conventional view locates the vast majority of art’s value in its intrinsic properties, along with the experiences that result from perceiving and contemplating those properties. Beauty, for example, is typically understood as an experience that arises from the artwork itself. According to the conventional view, artists use their technical skills and expressive power to create the final physical product, which is then perceived and enjoyed by the consumer.

The extrinsic properties, meanwhile, are mostly an aside or an afterthought; in the conventional view, they aren’t crucial to the transaction.

In contrast, in the fitness-display theory, extrinsic properties are crucial to our experience of art. As a fitness display, art is largely a statement about the artist, a proof of his or her virtuosity. And here it’s often the extrinsic properties that make the difference between art that’s impressive, and which therefore succeeds for both artist and consumer, and art that falls flat. If a work of art is physically (intrinsically) beautiful, but was made too easily (like if a painting was copied from a photograph), we’re likely to judge it as much less valuable than a similar work that required greater skill to produce.

So which ones are more important, the intrinsic or extrinsic properties? Here’s a crazy insight:

“Consider Leonardo da Vinci’s Mona Lisa, celebrated for its beautiful detail, the surreal backdrop, and of course the subject’s enigmatic smile. More visitors have seen the Mona Lisa in person—on display behind bulletproof glass at the Louvre—than any other painting on the planet. But when researchers asked subjects to consider a hypothetical scenario in which the Mona Lisa burned to a crisp, 80%8 of them said they’d prefer to see the ashes of the original rather than an indistinguishable replica.”— Robin Hanson, Kevin Simler, The Elephant in the Brain.

When you prefer the ashes of “the real thing” over something that looks exactly like the real thing (but isn’t), it’s clear that most of the value in a piece of art like the Mona Lisa is extrinsic, not intrinsic. In other words, it’s not the image that matters, it’s the certificate of authenticity.

This is what NFTs are: certificates of authenticity. You can copy the image, but you can’t copy the certificate of authenticity.

What’s the value of a perfect copy of the Mona Lisa, compared to the authentic Mona Lisa?

Something similar happens with the diamonds we were talking about. In a past life, I studied artificial diamonds from the funeral industry (you can turn ashes into a diamond for less than the cost of an equivalent mined diamond). Knowing this, when I was shopping for a diamond ring9, I asked jewelers why mined diamonds were more expensive than artificial ones even though they had more imperfections, and the conversation always went something like:

JEWELER: The imperfections are what proves they’re ‘real’.

TOMAS: I mean artificial diamonds are also real. You mean mined.

JEWELER: Yes, of course, both are real, but diamonds that come from the earth are the real thing, not some artificial thing.

TOMAS: So imperfections make a diamond valuable because they prove they’re not artificial.

JEWELER: Yes!

TOMAS: But imperfections make mined diamonds less valuable, right?

JEWELER: ...yes…

TOMAS: So let me get this straight: if a mined diamond has imperfections, it’s not very valuable. If it is near perfect, it’s extremely valuable. But if it’s completely perfect, it might be mistaken for an artificial diamond and so it wouldn’t be valuable anymore?

JEWELER: No, no! The mined diamond has a certificate of authenticity!

TOMAS: So what makes a diamond valuable is not really its perfection, but rather its certificate of authenticity?

JEWELER: It’s the combination: you want a diamond that’s as perfect as possible, because that’s super scarce, but you also want the certificate of authenticity, because otherwise it can be mistaken for an artificial diamond, which makes it common, and hence worthless. It’s the combination of the diamond and the certificate that makes it valuable.

This is what an NFT does: an image without a certificate is worthless. A certificate without an image is worthless. The value comes from the combination of the image and the certificate to prove you own the unique one.

Let’s go back to the art example to understand this better:

“Imagine that one of your friends, an artist, invites you over to see her latest piece. “It’s a sculpture of sorts,” she says. “Smooth swirls punctuated by sharp spikes. Rich pinks and oranges. Pretty abstract, but I think you’ll like it.” It sounds interesting, so you drop by her workshop, and there, perched on a pedestal in the center of the room, is the sculpture. It’s a delicate seashell-looking thing, and your friend is right, it’s beautiful. But as you move in for a closer look, you begin to wonder if it might actually be a seashell. Did she just pick it up off the beach, or did she somehow make it herself? This question is now absolutely central to your appreciation of this “sculpture.” Here your perceptual experience is fixed; whatever its provenance, the thing on the pedestal is clearly pleasing to the eye. But its value as art hinges entirely on the artist’s technique. If she found it on the beach: meh. If she used a 3D printer: cool. And if she made it by manually chiseling it out of marble: whoa! This way of approaching art—of looking beyond the object’s intrinsic properties in order to evaluate the effort and skill of the artist—is endemic to our experience of art. In everything that we treat as a work of “art,” we care about more than the perceptual experience it affords. In particular, we care about how it was constructed and what its construction says about the virtuosity of the artist.”—Robin Hanson, Kevin Simler, The Elephant in the Brain.

Remember how I mentioned at the beginning of the article that Everydays: the First 5000 Days was sold for $70M? Now it makes more sense. Making that piece was extremely hard. Beeple had to spend over a decade drawing every single day! Not only that, but Beeple was one of the first artists to play with NFTs. His first forays were quite successful, meaning that his masterpiece, the only one that would encompass all his drawings till that point, was going to make history.

That’s what the buyer was buying. History. The image might be replicable, the same way the Mona Lisa has been replicated a thousand times. But being the person who bought the first mega NFT, the result of 13 years of daily, painstaking work? You’re going down in history for that.

Here’s another example. For millennia, painters strove to discover the techniques that would make their painting come alive, as realistic as possible. Every genius would try to innovate on perspective, light treatments… And then suddenly, in the second half of the 1800s, there was an explosion of painting styles that diverged completely from this. Why?

“The advent of photography wreaked havoc on the realistic aesthetic in painting. Painters could no longer hope to impress viewers by depicting scenes as accurately as possible, as they had strived to do for millennia. ‘In response, painters invented new genres based on new, non-representational aesthetics: impressionism, cubism, expressionism, surrealism, abstraction. Signs of handmade authenticity became more important than representational skill.’”—Culture critic from the 1920s Walter Benjamin, through Robin Hanson, Kevin Simler, The Elephant in the Brain.

In other words: The representation of reality was valuable only because it was scarce. The moment it wasn’t scarce anymore (because of photography), the representation of reality itself lost all value, and people started valuing other things. Showing that it was never the image itself that was valuable, but rather its scarcity. Like the certificate of authenticity, which is what an NFT is.

This is very counterintuitive. We all look at art thinking that its intrinsic value is set, when in fact its price is determined by the scarcity of its extrinsic value: the artist, the style, the technique, the cultural resonance…

So what drives the extrinsic value of a work of art? For example, you might love one piece of art because your wife painted it. And you’d be willing to pay a lot for it. But if you’re the only one who values that—or one of a handful—the price of these pieces of art won’t increase by much.

For a painting to be very valuable, you need lots of people desiring it. That usually means they all agree on the extrinsic properties that make that piece of art valuable. In other words: there’s a social consensus on the extrinsic properties that matter.

This is crucial, because if the value of a painting is due to some social consensus of what extrinsic properties matter, then the same will be true of NFTs: their value will depend on what people agree are their most valuable extrinsic properties.

Social Consensus on Extrinsic Properties

Let’s summarize:

People want to burn cash to show their wealth.

Value is determined by scarcity. They need scarce things. Nearly any scarce thing can work.

But they need to avoid flaunting. They need plausible deniability.

Things that are acceptable to buy are thus scarce and with plausible deniability.

Social consensus drives perceived value.

This social consensus is a bit driven by intrinsic factors, but it mostly comes from extrinsic factors.

How does this social consensus emerge? First, it’s not like there are billions of artists that have found this consensus: Just 0.2% of artists have work that sells for more than $10 million, but a third of the $63-plus billion in art sales in 2017 came from works that sold for more than $10 million. This consensus happens very infrequently, and it usually comes from the very rich. What extrinsic factors are acceptable for them to consider something valuable art? Even the experts are super vague. This is a take from the most famous founder of Ethereum:

“But what exactly are these NFTs signaling? Certainly, one part of the answer is some kind of skill in acquiring NFTs and knowing which NFTs to acquire. But because NFTs are tradeable items, another big part of the answer inevitably becomes that NFTs are about signaling wealth.”—Vitalik Buterin.

Not very specific. Let’s ask another expert:

People collect NFTs for a number of reasons. It could be the thrill of discovering a promising new artist or artwork, the allure of a piece’s potential cultural value, the social status of owning something unique and canonical, or the prospect of turning a profit by reselling the work down the line.—Jesse Walden, NFTs make the internet ownable.

If you read this intently, you’ll notice all these reasons are the same: a blurry attempt at predicting what others will value10!

Many of the factors you can think of are linked back to scarcity. The death of an artist immediately increases the value of their work, not because it’s better, but because it makes it limited. Precocity is scarce. Being the first at something is scarce. The last. So what refers specifically to plausible deniability?

Luxury brands can shed some light. What, really, is the difference between every brand of watch? Of purse? Not much, besides the stories they use to define themselves. The foundation of the house. The designers working for the house. The drama. The famous people wearing them. Storytelling.

“Why are intangibles important? Why do brands bother with them in the first place? Once products start to travel further from home and into bigger markets, their producers need to give potential customers more information about them if they are to compete successfully. Because we are storytelling animals, this is often best done in the form of a backstory. Brussels lace, the uber-luxury good of the 16th century, was superior because it was spun from linen thread more delicate and beautiful than coarse English flax. The story went that Brussels lacemakers sat in damp, darkened rooms, with only a shaft of light to illuminate their painstaking work, so that the still-moist thread did not dry out, and finer and more intricate patterns could be created than would ever have been possible with thread that was dry and brittle. This story captured the imagination and kept the product at the forefront of customers’ minds.”—Spot the difference: the invincible business of counterfeit goods, Alice Sherwood, The Guardian

In art, belonging to history or shock value are also a source of storytelling value.

All of these speak to the type of brand it is, and as a result, the type of person who buys it.

The skill of a savvy critic is called discernement, which comes from French. Why is it not called discernimiento (Spanish) or simply judgment? Because critics want to signal they are good because they belong together with French tastemakers. In other words, they want to signal they are a traditional type of critic, educated in French art.

Somebody could burn cash on a Da Vinci or a Basquiat. Why do they pick one vs the other? Because it speaks to who they are. It tells others like them “I belong to the group of people who are traditional enough to appreciate a Da Vinci. I’m not transgressive, I like things to stay the way they are. The good things in life are proven.”

If you buy this bag from Hermès, at a nice $30k, you’re telling everybody that you’re rich, but also that you’re traditional, elegant, in-the-know, discreet. You won’t rock the boat. You conform to the rules of the elite.

If instead you buy this Judith Leiber for about $6k, you show you’re transgressive, modern, young, in-your-face.

Because this consensus emerges spontaneously, nobody knows what will become valuable, so art collectors look for authority figures who can validate some artwork’s value: the artist’s popularity, an association with a great collector (such as David Bowie), participation in a much-lauded exhibition.

In summary, aside from scarcity, it’s very hard to predict what type of social consensus on extrinsic value will emerge, but odds increase when a work of art belongs to history, has some shock value, has strong storytelling, is backed by some authority figure, and clearly allows buyers to express themselves.

The Bored Ape Yacht Club

You’re bored, you’re an alpha male, you have all the money in the world, and now success makes you bored? You’re welcome to my club.

Membership to BAYC is scarce. You need money, but also tech-savvinness.

Then, you need to add some storytelling for plausible deniability.

Bored Ape Yacht Club created rich and detailed iconography drawn from its founders’ personal tastes. The setting of an Everglades “yacht club” (an ironic appellation) was meant to evoke places like Churchill’s Pub, a well-worn Miami music venue that Gargamel and Goner frequented. “We were deeply inspired by eighties hardcore, punk rock, nineties hip-hop,” Goner said. “We’ve been calling ourselves the Beastie Boys of N.F.T.s.” From the scenes of an apocalyptic tiki bar on its Web site to the jaunty style of the apes themselves, Bored Ape Yacht Club felt more like the plans for a triple-A video game than an assortment of isolated N.F.T.s. The combination of sophisticated visuals, subcultural fashion accessories (shades of Hot Topic), and literary pretension made the Bored Ape universe catnip to a certain crypto-bro demographic. “We took lessons from the Hemingway iceberg theory,” Gargamel told me. “Ten per cent visible at the top, with all the scaffolding built out beneath.—Why Bored Ape Avatars Are Taking Over Twitter, Kyle Chayka

And then you make it a social club, with a “bathroom” (shocking!) to meet, because in the end it’s all about belonging to a social group.

A person buying a cryptomonkey from the Bored Ape Yacht Club is telling others: I am very rich. But I also get Web3. I understand the power of crypto. I know the current system doesn’t work. It will be replaced by something else. That is going to be decentralized, meaning the current centers of power of the establishment are about to be blown up by people like me. I want to hang out with people like me. Who else thinks like me (and is rich like me)?”

That’s why the list of owners of Bored Apes includes rappers, DJs, influencers, athletes, and the like. No politicians. No old-money billionaires. None of them belong to the elite that holds formal power11.

It also explains who might lean more towards a Bored Ape vs. a CryptoPunk. Bored Apes convey “cool social club”, whereas CryptoPunks, the original series with pixelated art, might appeal more to hardcore technologists like the founders of Shopify and Reddit.

How you burn your cash signals who you are and what group you belong to.

Takeaways

Do you think modern art is crap?

Do you enjoy art for its beauty, and don't care about who did it or in what way?

Are you perfectly happy owning copies of famous art you like?

Would you never buy a piece of art for a lot of money?

Or a luxury item for that matter?

Do you think card or stamp collectors are stupid?

If you answered yes to all these questions, you probably don’t understand NFTs, but you also don’t understand art or luxury. And yet you realize massive markets exist to cater to them. NFTs are the same. NFTs are luxury and art for the next generation.

As a result, art and luxury show us the key rules of NFTs:

Scarcity is everything. The more hardcore the scarcity, the better.

But you also need plausible deniability to avoid flaunting.

This is partly due to intrinsic factors of the NFTs, but mostly extrinsic factors.

Which scarce extrinsic factors matter emerges by social consensus, and include storytelling, shock value, belonging to history, halo effect from famous people, or endorsement from authority futures.

Their function is to signal belonging to an exclusive social group.

They reflect their identity.

For example, you can see many of these factors at play in Beeple’s Everydays: the First 5000 Days, which sold for $70 million:

He’s one, unique, famous artist. Scarce.

His piece was the result of 5,000 days of work: day in, day out. For 13 years, he didn’t stop. This is extremely hard to replicate. Baked-in scarcity.

The images themselves are not some programmatic composite. They are thoughtful. That’s scarce too.

Beeple Crap was one of the early movers into NFTs, which means buying his piece, you were buying a piece of history.

All of these made for perfect plausible deniability for a person who wanted to show they had money and believed in NFTs.

This paves the way for future NFT collections.

The Million-Dollar Question

After some of the original NFT collection mints were so successful, an avalanche of other collections appeared. That makes sense: anybody can start one. But the vast majority of the new ones are doomed to fail. Why?

There’s no intrinsic scarcity to NFT collections12. The huge advantage that early collections had was that they were early. They belonged to history. And they created a social club: you were buying a ticket into the social club of early crypto-experts. That was extremely valuable given the billions that crypto has generated. That’s gone now.

To be successful, a new NFT collection would need the following:

Clear, verifiable scarcity. You can’t mint infinite NFTs.

Compelling storytelling. It might include good characters, story arcs, origin stories for both the world and its creators, shock value, a statement piece, philosophy…

It needs some endorsements: from famous people for the halo effect, from authority figures like curators or famous exhibits13.

The harder the storytelling or the endorsements are to replicate, the more valuable the collection. More scarcity!

It must be targeted at a special group of people who are rich, tech-savvy, against the power establishment, interested enough about Web3 to buy NFTs, and who have an interest in belonging to the same group.

This last requirement is the hardest. Within the people who qualify, what’s a subset of them who don’t know each other already, yet would be very interested in signaling they belong to the same group?

I will share some thoughts on what these could be in this Thursday’s premium article: Why NFTs are perfect for political parties, religions, and NGOs; what’s the role of virtue signaling in NFTs; patronage; rights ownership; soulbound tokens; digital goods in videogames, and more. I will also explore some other ways that NFTs can be used beyond social signaling.

An NFT is a Non-Fungible Token: a digital thing (token) that can be verified cryptographically, through blockchain technology. In reality, they are today certificates of authenticity that you are the owner of something. Fungible means that can be replaced by another equivalent item. For example, one Bitcoin or one dollar are the same as another one, so they’re both fungible. NFTs, meanwhile, can’t be replaced. Each one is unique.

In the NFT, what’s unique is not the image file. It’s the certificate of ownership.

Easily one of my top 10 books.

I strongly disagree with this. Why two months? Why not four? Twenty? Two hundred? Two days? My hypothesis is that De Beers came up with this a long time ago to anchor people high.

Except they burn.

I believe its price is way above what it would be if it was only used for its industrial use cases. In any case, I’ll cover gold in a future article.

Your dream to show others your high status in the social hierarchy by owning a Ferrari.

Prinz 2013

Social pressure is still higher than my tolerance for explaining the diamond industry every time somebody looks at a ring.

Promising new artist → an artist that soon everybody will accept as having exceptional extrinsic properties.

The allure of a piece’s potential cultural value → a bet on what the culture will approve as exceptional extrinsic properties.

Something unique and canonical → something scarce, as defined by the extrinsic properties that are valuable.

The prospect of turning a profit by reselling the work down the line → a bet on what society will approve as good extrinsic properties.

Although maybe some of them were just given to these people as PR?

Like there’s no intrinsic scarcity to fiat money. Its scarcity depends on the printer, but anybody can print their own monopoly money. Which bills become valuable depends on the expectation of scarcity.

These endorsements might also come after the fact. If a group of art collectors agree that something is expensive, critics will appear to justify why they are so. These critics might then further opine on other pieces, creating a virtuous cycle of opinion authority and price increases.

Nit: fungible does not mean divisible, it means interchangeable (as in, a dollar bill or a digital payment token is conceptually an functionally identical to every other dollar bill / payment token in the world). NFTs are non-fungible because every one of them serves a different purpose (certifies a different virtual good). Or that's the narrative, anyway – nothing actually stops you from creating an NFT for an image that already has another NFT, so the "certification factor" of NFTs is actually somewhat extrinsic: what you are really buying is an entry on the Bored Ape website.

My answers qualify me as one who does not understand art and NFTs. But I have a story.

On February 27, 2022, I was performing in a comedy competition. After Russia's invasion of Ukraine on February 24, I slightly modified the ending of my standup set to show solidarity with Ukraine. As an afterthought I wanted to get a Ukrainian flag for my performance, but at that time they were not easily available yet. On the other hand here in D.C., there were many protests and some people carried flags. I saw a guy with a flag on Connecticut Ave., came up to him, and talked to him in Russian (I don't remember the Ukrainian language which I studied many years ago but never used). I asked to buy his flag. He was almost offended, he said it was his flag and he showed some dark spots which he said were a dried blood of his friends who were fighting in Donbas after 2014. I explained that I wanted to have a flag for a public performance and told him the lines I was going to use.

The guy changed his mind and he gave me the flag. He told me to take it and refused to accept any money. I said that I wanted to pay to support him in his cause. He said that there are places that need my money more than he does. I said that I'll give him the money and he can use it as best he knows. He agreed. I emptied my wallet of all my paper currency, which was over $90.

I have the flag. Today, Ukrainian flags are easily available and relatively inexpensive. But MY flag has a story behind it. And dried blood.

Victoria

P.S. When I unexpectedly pulled out the flag at the end of my standup set I received an ovation. In the end, I took the 2nd place out of 14 performers.