Who Owns the Megaphone?

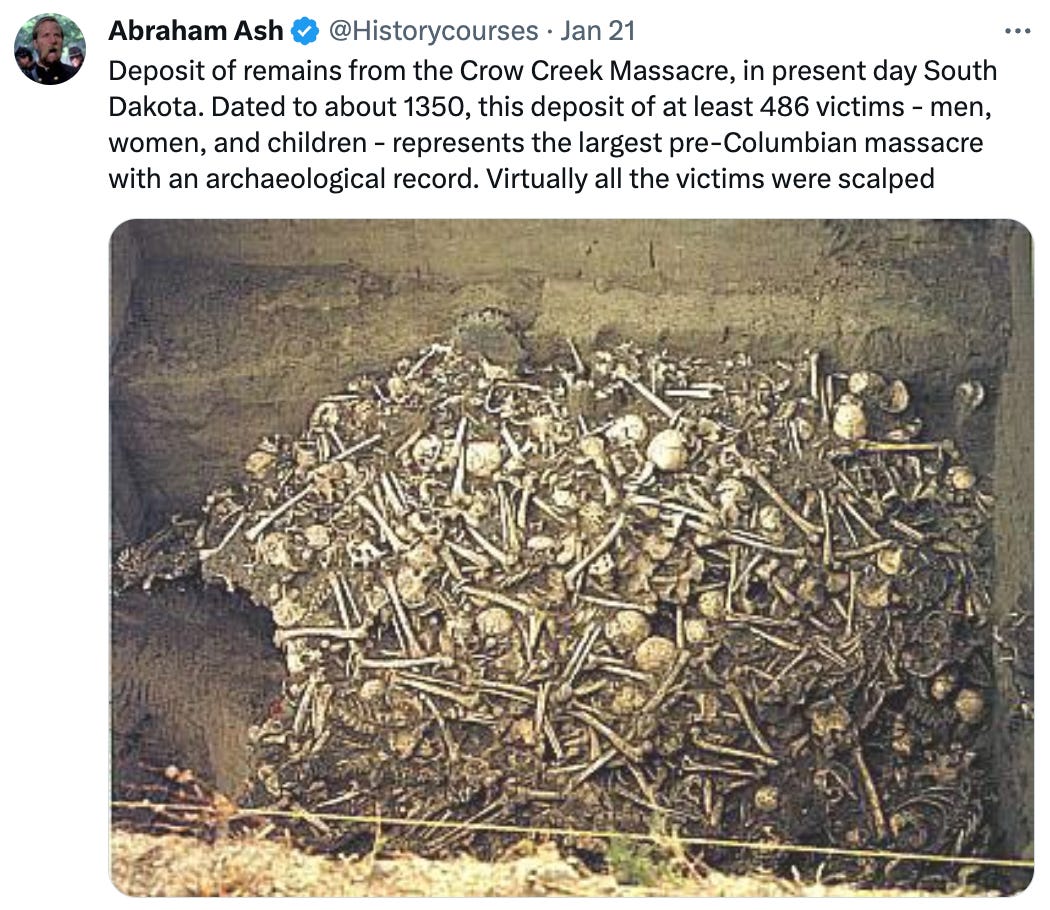

Since Elon Musk bought Twitter, I’ve suddenly started seeing stuff like this:

This stuff is anathema.

This is forbidden.

This is the kind of stuff that got Adam and Eve kicked out of Eden.

And yet here we are, witnessing blasphemous research.

Is any of it true? I don’t know. I’m skeptical of claims like these until I dive into them. I started studying them independently. I’ll talk about them to premium subscribers only—they’re too polemic.

So today, we won’t talk about the content of these claims. What really surprises me goes one level above: How come we get to see these claims at all? And what does it mean for society?

I did not see this kind of thing before Musk bought Twitter. If this is true for many other people, then the change in ownership of a social media network has the potential to change public opinion—and hence the arrow of society.

The Arrow of Speech

We imagine free speech as this perfect market of ideas; it’s nothing but.

Society has obsessed about who captures and biases this market of public opinion for thousands of years.

The Greeks had it easy: They managed their affairs by gathering a small group of elite men in a single room. But even they were obsessed about obfuscation of the truth. They pondered at length over rhetoric, populism, manipulation, logic, and truth. They knew that emotion and manipulation could mask the truth. For example, thanks to his rhetorical skills, Socrates was influential enough to be formally accused of corrupting the minds of the youth of Athens. He was sentenced to death to censor him.

In the Middle Ages, the Church had a monopoly on information because it had a near monopoly on education, Latin, and the Bible. Like gorillas at the door of a club, only priests could give you access to God, so you’d better obey. This created a pretty uniform culture in Christian Europe that could force kingdoms to go to war overseas.1 In the freakin’ Middle Ages!

The Church controlled the megaphone.

The Church’s control went beyond that. Through the Inquisition and other means, it could control even what specific individuals said. But it didn’t bother with this too much. It didn’t persecute blasphemy unless it started picking up steam. What gave the Church power was not so much control over speech, but control over the megaphone.

And then the printing press appeared and within decades obliterated that monopoly.

Books

An explosion of thought followed, birthing the Enlightenment, the Scientific Method, Protestantism, and wars of religion. The Church didn’t have enough control over the presses, and hence new ideas spread like water splashed on marble.

Why did Protestantism appear in Germany and not, say, France? Because back then, Germany was part of the Holy Roman Empire—which, according to Voltaire, was neither holy, nor Roman, nor an empire. Indeed, the emperor had little power over its fiefdoms.

One territory would have printing presses in favor of one faction, another in favor of another, books could flow from one to the other, and soon you had uncensorable information flowing everywhere.

Consider what happened in France around that time: The king got scared of Protestants and in 1535, he enacted an extreme statute forbidding all printing under threat of hanging and closing all bookshops. Nevertheless, books flowed from Germany and Switzerland. The statute couldn’t be enforced, so it was disregarded.

The fact that the Church had an index of forbidden books that Catholics were not supposed to read tells you all you need to know about its ability to suppress heretical books: It couldn’t, so it had to resort to asking others to enforce the ban for them.

This was not true in other places. In China and the Ottoman Empire, governments had enough power to ban printing presses. The result is2 that from 1500 onwards, the Ottoman Empire and China decayed while Europe surged ahead.

This doesn’t mean that the Truth bathed Europe in its warm light. Disinformation spread like wildfire. Take the Malleus Maleficarum.

Written by a clergyman, it was supposed to explain how to identify and capture witches. Publicly denounced by the Church—and even forbidden—it nevertheless became popular, and many other similar works appeared later, like Flagellum Daemonum, A Discovery of the Impostures of Witches and Astrologers, or Compendium Maleficarum. These types of works fueled the witch trials.

Misinformation was not just about witches. Here’s one about biology and nature:

And here, Mercurius Bellicus reports Charles I’s death… one year before it happened.

This chaotic process, however, turned out to be better than the monopoly on speech. For each Malleus Maleficarum, we had books like Christopher Columbus' Letter on the First Voyage, Nicolaus Copernicus' De revolutionibus orbium coelestium, outlining heliocentrism, and the Encyclopédie.

The cheaper and easier it was to set up a press and to fill it with content, the easier it was for ideas to spread—both information and misinformation.

The reduction in the cost of supply fostered an increase in demand. People became more literate.

With cheaper supply and higher demand, production of books exploded.

As book costs went down, another business model became viable: news.

News

Journalism emerged in the 1600s. To give you a sense of what people thought about fake news back then, this is the subtitle of England’s Licensing of the Press Act of 1662: “An Act for preventing the frequent Abuses in printing seditious treasonable and unlicensed Books and Pamphlets and for regulating of Printing and Printing Presses.”

News was always easier to control by governments than books, because news presses need to print recurrently for the same newspaper. This means that special interests could sway public opinion, if those in power let them. In 1600s England:

“A king's messenger had power to enter and search for unlicensed presses and printing. Severe penalties by fine and imprisonment were denounced against offenders.”3

The press was gradually freed in England when the Licensing of the Press Act was not renewed in the late 1600s, searching for illegal presses was outlawed in 1765, and news taxes were eliminated during the 1800s.

France was slower to adopt freedom of the press. Up until the 20th century, the government tightly controlled all media to promulgate propaganda to support the government's foreign policy of appeasement to the aggressions of Italy and especially Nazi Germany. There were 253 daily newspapers, all owned separately. The five major national papers based in Paris were all under the control of special interests. Many leading journalists were secretly on the government payroll. The regional and local newspapers were heavily dependent on government advertising and published news and editorials to suit Paris.

Although the US has a 1st Amendment that theoretically protects the media from government interference, there have been serious levels of censorship throughout its history, including in the 20th century. Propaganda during WWI and WWII was rampant, and what newspapers could print was heavily restricted.

But the 20th century saw a new technology that would push the boundaries of news further.

Radio

The radio created the first modern political debate, and it helped people like FDR, Churchill, and Charles de Gaulle liberate the world in WWII.

For centuries, people had read politicians’ words. But radio made it possible to listen to them in real time. Politicians’ personalities all of a sudden started to matter more. The way their voices sounded made more of a difference. And their ability to engage and entertain became crucial components of their candidacies.—Source.

Radio also created the sound bite, making us somewhat dumber. More importantly, it allowed people to hear words directly from those who spoke them, partially disintermediating journalists.

Some people took advantage of that: The radio offered its share of misinformation, like the panic caused by Orson Welles’ War of the Worlds. But radio conformed to political powers better than the press had: Radio frequencies are scarce, and the equipment to broadcast is not cheap. So it’s easy to regulate. The result was that governments took control of the media and imposed rightthink:

Mainstream radio was created in the early 1920s and rose to prominence such that in 1930, about 50% of US households had one.

Here’s what Goebbels, the Nazi minister for propaganda, had to say about it in his speech The Radio as the Eighth Great Power, which he gave in 1933, just after the Nazis took power:4

Napoleon spoke of the “press as the seventh great power.” Its significance became politically visible with the beginning of the French Revolution and maintained its position for the entirety of the 19th century. The century’s politics were largely determined by the press. One can hardly imagine or explain the major historical events between 1800 and 1900 without considering the powerful influence of journalism.

The radio will be for the twentieth century what the press was for the nineteenth century. With the appropriate change, one can apply Napoleon’s phrase to our age, speaking of the radio as the eighth great power. Its discovery and application are of truly revolutionary significance for contemporary community life. Future generations may conclude that the radio had as great an intellectual and spiritual impact on the masses as the printing press had before the beginning of the Reformation.

It would not have been possible for us to take power or to use it in the ways we have without the radio. It is no exaggeration to say that the German revolution, at least in the form it took, would have been impossible without the radio.

We live in the age of the masses. The radio is the most influential and important intermediary between a spiritual movement and the nation, between the idea and the people.

Then, Nazis proceeded to take control of all stations, started filling the content with propaganda, and built cheap radio receivers so that everyone could hear it. From 1933 to 1944, the number of radio stations shrunk by 75%, and the share of stations directly controlled by the Nazis increased tenfold.

The Nazis forbade listening to foreign-sourced content under penalty of death. This is how important control of information was—but it also tells you how much control Nazis had over that—little. You can’t control the airwaves, so even they had a hard time fully controlling the narrative.

TV

That said, radios are more easily controlled than books, and TV stations are even more so, with significantly higher costs for set-up and content creation.

People’s thoughts were constrained by what the government wanted us to hear. By the mid-20th century in the US, the Big Three networks (ABC, CBS, NBC) accounted for most of the TV viewership in the country. Having only three networks, it made sense for them to cater to the widest audience—that is, the political center. Government oversight was also easier. These meant power concentration in TV led to civil debate.

But TV rightthink also limited freedom of thought.

Most people think that the Internet broke this, but that’s not completely true. In the US, the Fairness Doctrine broke it first:

The Fairness Doctrine was a US policy that required the holders of broadcast licenses both to:

Present controversial issues of public importance, and

To do so in a manner that fairly reflected differing viewpoints.

It took Americans 35 years to abolish it in order to foster free speech. This reversal gave birth to beacons of democracy like Fox News and CNN, and as cable news erupted and radio was freed, so did polarization.

The Internet exploded this trend, making everybody an unbridled content creator. Social networks gave anyone the ability to reach millions of people.

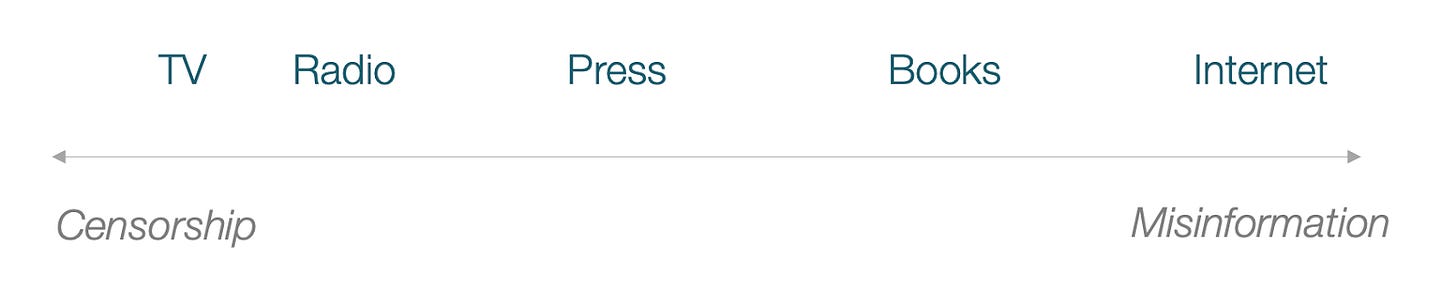

If we look at all these examples, then, it looks like you have to choose the lesser of two evils: censorship or misinformation:

But maybe there are ways to get the best of both worlds?

Rules of Engagement

You don’t want to give any leeway to the government on what speech it can or can’t ban, because it will eventually abuse that power. Things like “speech is banned if it’s morally reprehensible or of poor taste” or things like that are a recipe for disaster.

We’re seeing this in the UK today. Section 127 of the Communications Act of 2003 says you can go to jail if you send by means of a public electronic communications network a message or other matter that is grossly offensive or of an indecent, obscene or menacing character; or if you post content to annoy, inconvenience, or needlessly cause anxiety to another. Needless to say, this is a door wide open for government abuse, And how many people does that represent? Over 1,000 per year. They have said things like:

“Crap! Robin Hood airport is closed. You’ve got a week and a bit to get your shit together otherwise I’m blowing the airport sky high!!”

“If there is any consolation for finishing fourth at least Daley and Waterfield can go and bum each other #teamHIV.”

Should we ban this type of poor-taste joke? Or is social enforcement good enough? Who stops the government from deciding that “grossly offensive” is anything that doesn’t abide by rightthink?

So government rights of censorship must be limited. But they are not zero. Falsely screaming “Fire!” in a theater—or more broadly, inciting imminent physical harm through speech—is illegal. We agree that child pornography is illegal. There are limits to free speech, and the world is better for it.

Was the Fairness Doctrine good or bad? The rule was “talk about important stuff by covering both sides”. It sounds like a harder rule to abuse by the government. It certainly looks like the type of censorship in 1960s US television was less destructive than that of the Nazis. Was the Fairness Doctrine good because it gave freedom of speech while setting up rules of engagement?

European countries go further and ban Nazi propaganda, terrorism propaganda, and even pro-Palestinian propaganda. Is it good or bad? On its face, it looks good. But maybe the terrorists of today are the liberators of tomorrow. The Arab world definitely thinks this is the case in Palestine. Should we prevent Hamas’s ideas from spreading at all? Or should we expose them for what they are?

Then there’s what’s legal vs what’s moral. I feel more free talking in Europe than the US: The US has its own kind of censorship—social censorship.5 This relates most to culture wars, but sex is arguably more blatant. Americans get alarmed about things like nipples and adultery in a way that leaves most Europeans dumbfounded. This extends to their social networks, whose ban on any borderline sexual content is a way to export American prudishness to the world. Is that OK because it’s private so it’s subject to market forces? Or waiting for market forces to act might allow a young human to be educated by pernicious forces? What if Disney bans poop? Disney has been around for a century, and its impact on society is huge—especially young children. Do parents need to be on top of all Disney and Youtube content, approving and countering the content of their children at every step? Isn’t the point of that content to give parents time?

We have centuries of experience in mass media and still can’t figure out the right answer. With social media and the Internet, how should we think about this in the 21st century?

21st Century Censorship vs Misinformation

The Bezos types have always bought the Washington Posts of their times. In fact, it was way worse a century ago:

Newspapers reached their peak of importance during the First World War, in part because wartime issues were so urgent and newsworthy, while members of Parliament were constrained by the all-party coalition government from attacking the government. By 1914, Alfred Harmsworth, count of Northcliffe controlled 40% of the morning newspaper circulation in Britain, and 45% of the evening. He eagerly tried to turn it into political power, especially in attacking the government in the Shell Crisis of 1915. Lord Beaverbrook said he was, "the greatest figure who ever strode down Fleet Street." A.J.P. Taylor says, "Northcliffe could destroy when he used the news properly.”—Source.

What’s different now is that we have social networks, which use network effects to amass a massive amount of power. And not just in one country, but across many.

So how much of a problem is it that Musk owns Twitter? Is it good that he is more lenient about misinformation, or should he censor more, the way the previous management did? Or should he influence Twitter in a different way?

For example, current algorithms optimize for engagement. But engagement optimizes for emotions. So Twitter naturally incentivizes rage, fear, and hatred. Nobody coded these things into the algorithm. They’re just a result of our human biases. So should Twitter management push the tool towards a more reasonable direction? Should it encode rules of engagement in virality?

Instead of doing that, Twitter has released Community Notes, which uses the audience itself to fact-check the content. This is working quite well. Is that the right rule of engagement—give an opportunity for debate to emerge? Do we hinder the right solution by asking the government to overcensor?

I am glad I’m getting to see the papers I mentioned at the beginning. They are shocking, but Truth is good. If they are true, I want to know. For example, if it’s true that there are IQ differences in races, then we should know, because our democracy and capitalism are not designed for that. They’re designed for a world where anybody can do anything if they only try hard enough.

What about TikTok? How much of a problem is it that the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) controls it?

Apparently, TikTok is limited to 40 minutes a day in China and is focused on educational and patriotic content, while the West receives all the most addictive content without limits.

They make their domestic version a spinach version of TikTok, while they ship the opium version to the West.—Source.

Do we want to give the CCP power over public opinion in the US about the Israel–Palestine conflict? We spent years decrying a few ads from Russian bots on Facebook, but we find it perfectly normal that the CCP indoctrinates the youth of the Free World for three hours every day?

What about OpenAI? 15% of Americans use ChatGPT. But it’s famously woke.6 I stumble upon its righteousness in about 20% of my searches, which prevents me from doing unbiased work. If you push this to a massive scale, is ChatGPT going to make humankind more woke? Is this right?

Or maybe OpenAI won’t be able to monopolize speech, and its self-censorship will hinder its growth, so that other AIs appear with less bias. This is what Google’s Gemini and Twitter’s Grok seem to be doing.

I don’t have an answer to all these questions. Here is where I’m landing so far:

As a rule of thumb, sunlight is the best disinfectant. More freedom is generally better.

Banning speech that fosters imminent violence is reasonable.

I don’t know what other rules of engagement are reasonable in every situation.

The Fairness Doctrine seemed to be reasonable, hard to hack, and conducive to productive debate. Should we apply it again?

I would be interested in exploring rules of engagement like the Fairness Doctrine for social media. But what would they look like?

Past examples of censorship are quite bad, like how the Church suppressed growth in Europe, or how Germany fell into Nazism. Today, what the UK does to Brits on Twitter sounds unreasonable. We should not give the government many powers to censor speech.

Oligopolies in mass media are dangerous. We should avoid them.

This is especially true in mass media, where the owner can substantially influence the editorial line.

This is less true in social media, where the owner is not the poster.

I’m interested in social media tools that allow for debate rather than making single opinions viral. Community Notes is the way to go.

That said, we should be extra wary of bad actors substantially influencing speech. It is madness to me that Free World countries give the CCP an open door to fill the minds of its youth. We should ban this type of influence, even if it’s only algorithmic. We can’t let China own the megaphone.

What do you think? What should we do?

I will write about some of the “forbidden topics” in the coming weeks, only for premium subscribers. Subscribe if you want to read those articles.

The crusades

The printing press is not the only reason, but it is one of the big reasons for all of this.

I often edit quotes to keep the original spirit but make them clearer and more focused on the topic at hand.

But at least there’s little risk of government overreach.

E.g. jokes about white men and Jews are OK, minorities and Palestinians are not.

What a great way to open the debate!

I hesitate to write before letting this information sink in a little deeper...

Just one thought for the moment : I reduced my use of social network precisely because the algorithms lead me to extremes. I wish they would do the opposite : draw me towards people who, like me, search for compromises over conflict. A Twitter of Grey VS black or white.

Absolutely GREAT article. I especially loved the survey of free speech vs control of speech going all the way back to the Greeks. Also a minor note about how TikTok (controlled by China) "is limited to 40 minutes a day in China and is focused on educational and patriotic content, while the West receives all the most addictive content without limits." What does that remind me of? Oh, yeah, the Opium Wars. What goes around comes around??