Why Is Fertility Down, and What Can Be Done About It?

An Interview with Lyman Stone

This is the 4th article on fertility. Today, I share the first part of the interview with Lyman Stone, edited for brevity and clarity. The second part will come in the premium article this week1.

Here are the articles on fertility so far triggered by my conversation with Stone:

Here are some of the topics we cover in this one:

How many kids did ancient societies have?

Why Greece and Rome were outliers in size, and why Romans stopped breeding

Why the oldest surviving cultures are heavily pro-natal

How lower fertility spreads from rich to poor countries

The court case that single-handedly dropped fertility in the UK

Why fertility keeps going down in developed countries

What happened in Greenland to demolish its fertility overnight

The role of Disney and Instagram on all of this

How much it costs governments to increase fertility

How can they nudge it in one or the other direction for free

Why society should have more babies, and how that improves the environment

Why the degrowth movement is racist, and why promoting fertility reduces racism

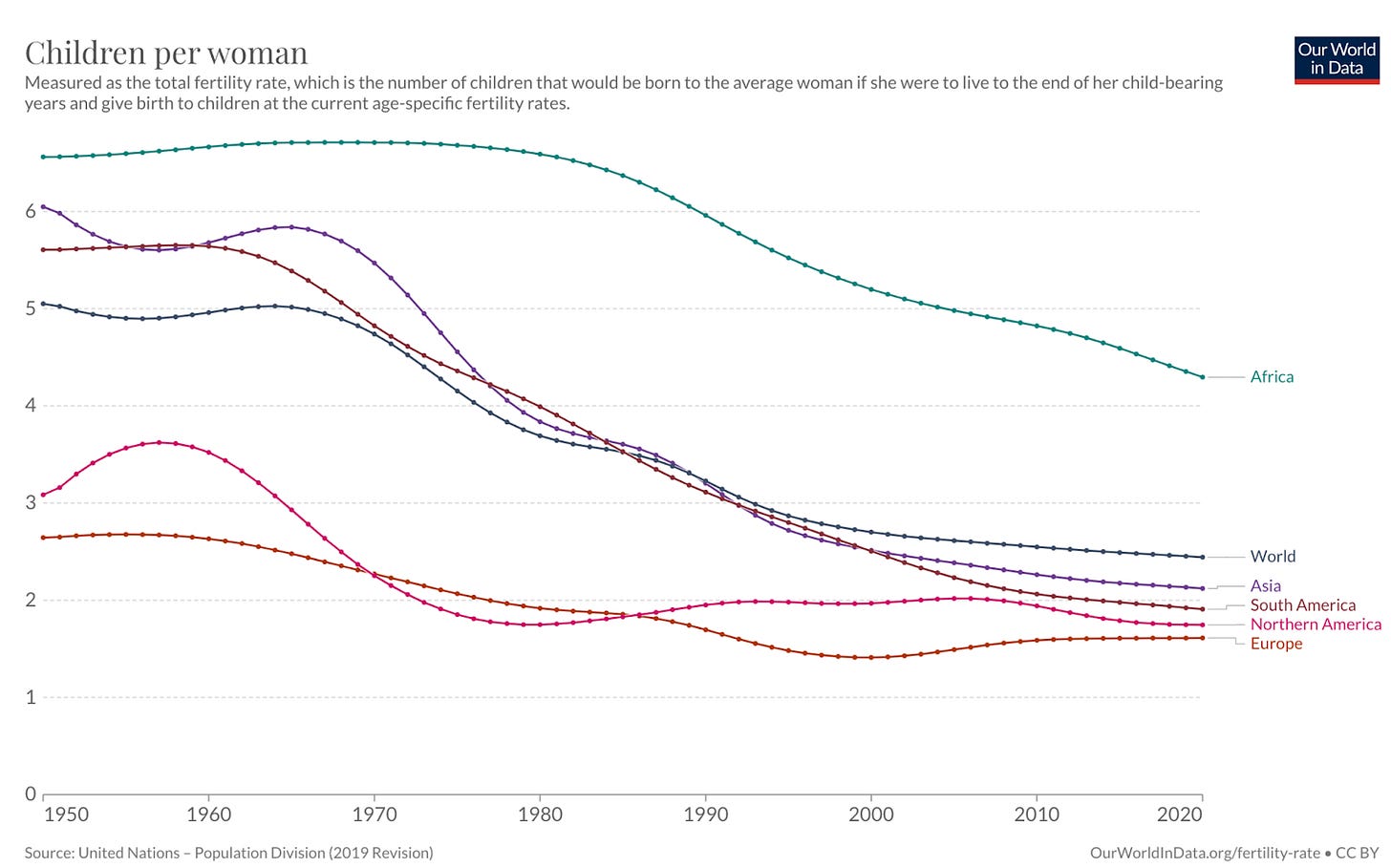

TOMAS PUEYO: Across the world, fertility levels are going down.

This is happening in nearly every country in the world: fertility is either below the replacement rate of 2.1, or going there.

I can’t find a single country that was below 2.1 that has been able to go back above 2.1. If this is true, the population of the world is going to start shrinking in the next few decades. Here are my questions:

Is this really happening?

If it is happening, what are the main drivers that are causing this?

Has anybody been able to revert this? And if so, what lessons can we apply to other places?

LYMAN STONE: You have to step back 500 years.

TOMAS PUEYO: I love it!

LYMAN STONE: Demographers used to think that, around the world, 500 years ago, most cultures had what’s called “natural fertility”: no control of fertility. People were having babies as often as they had sex divided by nine months.

We now know that's not true. That's not what the pre-modern world looked like. In fact, there were pre-modern societies with fertility rates as low as 2.8 and as high as 12. There was a lot of variation. But what is true is that:

It was fairly difficult to control fertility—it took more effort than it does today.

Fertility tended to be higher and nowhere was it below 2.8. After you account for child mortality, the average family size, the average number of surviving children was probably ~3.

TOMAS PUEYO: That survival is to puberty, right?

LYMAN STONE: Yes. Pre-modern societies sometimes had periods of very rapid growth, they would breed to the maximum food capacity of their economy, but then they would hit various kinds of natural limits on their growth, often related to low agricultural productivity, and then they would tend to decline again. You got these boom-bust cycles in growth throughout.

TOMAS PUEYO: How did that work? Were there massive famines?

LYMAN STONE: You have what are called the “classic Malthusian positive checks”: things like famine, or reduced nutrition that increased susceptibility to disease, or as people felt more resource strain, they tried to avoid having children.

Another example: If men need to have a certain level of resources to get married, and there’s few resources around, the marriage gets delayed. That reduces the amount of time to have babies. In a lot of pre-modern societies, we do see quite a late average age of marriage for men in particular. There's lots of ways pre-modern societies reduced fertility, sometimes intentionally, often not intentionally.

Another example: with delayed marriage, males begin to have more sex with prostitutes, which leads to more venereal disease, which leads to greater biological infecundability…

There were some exceptional pre-modern societies that could reach a very large scale. The city of Rome reached a million people, for example. And there's a pretty strong argument that the population of mainland Greece was around five or six million, which it doesn't reach again until the 20th century.

These were large, sophisticated civilizations that used long distance trade to increase their local carrying population capacity. But these are exceptions. In most cases, classic Malthusian positive checks were at work in these societies.

Then, about 500 years ago, modernity started changing things.

Most people think the first way modernity influenced fertility is through better living conditions, but the first major impact was instead changed values and attitudes: you get the enlightenment, you get the Renaissance, you get these things to start to change how people think about the world.

[This part of the interview is what spurred the article from two weeks ago. If you’ve read The Twin Revolutions of Politics and Fecundity, you can skip it.]

The earliest documented fertility transitions—I actually hate this characterization—push fertility below 2.5-3. There are two of them that happen more or less simultaneously: France and Massachusetts. And as you know, these two regions also went through a unique historic moment at the end of the 1700s: revolutions. Why? What do they have in common?

The root of both fertility transitions is secularization: the first wide-scale popular secularization in human history.

For example, we get clear evidence from wills and bequests in France that the areas with most secularization were also the areas with the biggest fertility drops. In Massachusetts, we see lower Church membership over the 18th century.

So we see there's the secularization of society that leads to a greater desire for small families, greater acceptance of limiting family size, and the emergence of modern individualist norms.

What happens in Massachusetts and in France over the course of the 18th century? Revolution! As a demographer, it's not wildly surprising: the same places that give rise to the demographic transition are also your first two hotbeds of revolution. I'm not saying that the change in the age ratio caused the revolutions. I'm arguing that both these political revolutions and their demographic change were causally related to an underlying shift in values.

That shift in values has probably happened before in many times and places, but it may have been maladaptive so it didn't survive. But the 18th century also saw another important shift: industrialization, urbanization, the start of modern economic growth—which allowed way more growth than was possible in the past. These two things together, smaller families and high economic growth, could become adaptive, survive, and spread throughout the world, and that's what's happened.

TOMAS PUEYO: How is lower fertility adaptive in an industrialized world?

LYMAN STONE: You can imagine why low fertility is not very adaptive in a pre-industrial world, right? Lots of children die, so you need to have a lot of children for a group to persist. High fertility is highly adaptive.

But low fertility obviously is adaptive as well, right? If you suppress your fertility, you have more resources for yourself and for the smaller number of children that you do have. It's a quality-quantity trade-off. Under certain circumstances, suppressing fertility is properly adaptive.

To add to the problem, sometimes what’s optimal for the individual is not optimal for society as a whole, and vice-versa. We actually see this in the historic record.

Famously, the Roman emperor Augustus cannot get Roman elites to breed. He just can't get them to have babies. Why? Because those elites realized that it was highly adaptive to only have a few babies. But Augustus said: “Yeah, it's adaptive at the individual level because you don’t split your inheritance as much, but for the empire it’s a catastrophe because we really need loyal Roman elites to populate the exploding number of bureaucratic positions around the empire.”

So there’s a tension between what’s optimal for society and what’s optimal for individuals. In some societies, as a family, there was a rational reason to have many children; in others, it might have been rational to have only a few.

But it was probably catastrophic at the society level to adopt the habit of having few children at a wide scale. And this is why almost every old cultural value set in the world is explicitly pronatal.

People have this idea that having babies is deeply hardwired in our genes.There is some evidence for genetic roots of fertility preferences, but the reality is that every single long-lasting culture that we know is interventionist: explicitly, overtly pronatal.

They actively try to create norms and encourage childbearing, which to me suggests that cultures have developed in conflict with alternative anti-natal visions, right? When you see that every culture in the world has a really explicit position on an argument, you shouldn't just assume that they never argued that position in the past. It probably happened a lot. One side of that argument (having few kids) was not highly adaptive in the past, and didn't get passed on.

But today, it’s not the case anymore. Child mortality is lower. The amount of resources, status, and advancement that is foregone by having a large family is exponentially larger. So the advantages of suppressing fertility at the individual level are probably much bigger, and more people do so.

In particular, economic growth is becoming more and more dependent on very complicated knowledge and human capital intensive processes that require more intense child-rearing inputs. It takes more years to train an engineer than a farmer in a subsistence farm, so you need more inputs to sustain their level of productivity.

TOMAS PUEYO: Yes, at the individual level this might be optimal. But it sounds to me like at the societal level the math would probably favor more quantity.

LYMAN STONE: This is the big argument. In the historic timeline that we have experienced thus far—the last 200 years of industrialization—quality gets favored (and I hate these terms, quantity and quality. Quality means a kid who gets more years of education, not actually a higher-quality kid). As our society has gotten more sophisticated, the returns to investment in human capital are much higher.

It’s called skill-biased technical change. Our society has changed in technical ways that favor more skills, but more skills require a lot more parental inputs for children to acquire them. And that means that if you have a lot of kids, that your kids are basically less competitive. They do less well in life. No parent wants that for their kids. There's also other norms involved here, but that's the explanation for why this becomes highly efficient and adaptive at the individual level: skill bias. Technical change means that even if parents want a big family, they are forced for the wellbeing of themselves and their children to play this quality game.

And then, societies that invest in educating their children become richer, more prosperous. They develop even faster technologically, and because they become richer, individuals and other societies look at them and say: “I want to be like that!”

And this leads to the spread of something called developmental idealism. Developmental idealism is the idea that people in poor countries look at the rich countries and they say: “Gosh, we'd like to be healthy, wealthy, and prosperous. Maybe democratic. How do we get there? Maybe we should have fewer babies.” And that’s the story that's been told to poor countries.

Is this story true? I would actually argue it's not true, but it’s the story that's been told to them: if you want to develop, if you want to get healthy, wealthy, prosperous, maybe democratic… If you want to be modern, you have to moderate your family size.

TOMAS PUEYO: This is fascinating. I have never heard of developmental idealism before. It leads me to two questions.

First: Does this just happen? Or are there stakeholders that push this narrative?

Second: What is the evidence on developmental idealism?

LYMAN STONE: Yeah, these are great questions, and they actually go together.

There’s a broader set of theories called ideational roots of demographic change, which believe that demographic changes are largely driven by changes in ideas. Obviously, we can never fully separate ideas from economic circumstances, but to the extent these are separable, ideational theory suggests that ideas are the most important factor influencing demographic change.

But what ideas? Which ones drive the most important demographic changes, and in what direction? Developmental idealism is a theory advanced by Arland Thornton, according to which development is idealized, and people assume they need to reduce their family size to achieve it.

People observe the wide disparities in health, wealth, prosperity around the world, and they want to improve too. There's some exceptions, but that desire is close to universal. What is much less universal and much more controversial is that, to achieve that development, you also need to adopt all these other trappings of modern society: you should have two children, your children should be highly autonomous, you should accept divorce, marriages should be based on love, not arranged; remarriage should be permissible, but not required, etc.

There's actually good survey work on this, asking people around the world a battery of questions about developmental idealism. What we find is:

Adoption of it is strongly correlated with exposure to Western mass media.

It does predict lower fertility.

We also have a lot of other studies looking at specific events that caused dramatic shocks in developmental idealism. For example, there’s this court case in the United Kingdom, in the 1870s, that changed public taboos around talking about family size limitations almost overnight. Wherever this court case was covered, fertility fell way faster and it happened immediately.

There are other cases like Quebec, where I live. Quebec still had a high and stable fertility through the 1960s, but within 10 years it went from 3-3.5 children per woman to below 2.1. How did it happen in just 10 years? Well, it was at the same time as the Catholic church was booted out of its public role. The nationalist movement took over Quebec politics, and you got this rapid promotion of an idea of development that the Quebec nation needs to enter modernity. We need to develop, which means get rid of the Church, industrialize, and adopt the small family ideal. When you talk to people today in Quebec, this is what they say, it’s developmental idealism: the Quebec nation needs to seize modernity and adopt small family sizes.

As I said, developmental idealism is just one theory of ideational change and how it works, and it's not universally accepted among demographers today, but it has a decent amount of evidence for it. There's a debate about exactly what ideas matter. We talked about secularization as one of these ideas. There's another theory called the second demographic transition that says it's actually about individualism writ large.

Regardless, these ideas spread. But how did they spread? Who spread them?

One is self-interested actors in wealthy countries. They have an interest in propagating ideas that are friendly to their values. A Marxist would tell you that Westerners push individualism and liberalism because the modern family is amenable to capitalist expansion.

Another is that the West came to dominate the rest of the world, so Westerners chauvinistically just assumed that history was linear everywhere, and the other countries would become like them, one way or another.

This is the core of the developmental idealism theory. Westerners didn't want to promote the modern family. They just assumed that the modern family was a vital part of economic development, so they just propagated it almost out of benevolence. This is the NGO—Non-Governmental Organization—argument that we're going to help a country develop by improving contraceptive access, assuming that adopting a more Western family norm is an important part of becoming healthy, wealthy, and prosperous.

This is empirically debated. Some people argue with good evidence that these changed family norms really are super important for becoming healthy, wealthy, and prosperous. Other people also argue with decently good evidence that it isn’t true. These aren't bad faith arguments. These are good faith arguments among people who are all well-intentioned.

The debate comes down to: are individual autonomous agents in traditional societies freely seeing a better vision of life and choosing it for themselves because they really like TV, soap operas and that lifestyle? Or has the West pushed these ideas?

I should mention that, sometimes, IMF—International Monetary Fun—loans and World Bank development programs have demographic conditions like: “You have to lower your fertility rate to a certain amount, if you want a loan.” Sometimes, it’s explicitly conditional.

You can also think of the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs) or the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). All have these goals like “Get unintended pregnancy to this, get teen pregnancy to this.” Nowhere do they say: “Try to make the fertility rate match what people say they want.”

The MDGs, the SDGs… They don't care what locals actually want. They're set on objective, developmental criteria, without any reference to what locals may desire for themselves2. So the debate comes down: How do you interpret this change in ideas? Is it the progress of liberty? Or is it ideological colonialism?

This is very debated. I, of course, have my personal view on this, which I have not hidden very well: this ideological spread has elements of deception and coercion by richer countries against poorer countries. And I don't think that this spread of ideas is purely people making well-informed rational choices, choosing to adopt a Western family norm purely because they think that fewer children is good in itself. I think, often, people adopted this smaller family size as a tool to become healthy, wealthy, prosperous.

If you talk to another demographer, they'll say: “We invented vaccines, antibiotics, and good sanitation, so mortality went down, so people didn't need to have as many kids, so they didn't. That story is called the modernization hypothesis and it used to be what everybody thought. It was THE theory.

But very few demographers believe this theory anymore. Because, empirically, it turns out to be a bad explanation of the timing and speed of changes that we observed.

Material circumstances do matter to some extent. And, indeed, I said before that small family norms existed in the past, but because of material conditions, they could not survive.

Material conditions today have made its spread possible, so they matter. But they’re a necessary condition, they’re not sufficient. They have a supporting role. Material conditions make it possible for this ideological change to finally break through and do its thing.

So this is the story that explains the transition from 3-12 babies before modern times to the current 2: improvements in medical technology may admit that having fewer children no longer led to your society rapidly declining, and so the norms around small family size and individualism and the autonomous agency and all these things were able to spread without being self-defeating. They led to greater economic growth, which led to those societies being admired and propagating their views to separate societies.

That doesn't explain the last 20 years. What we've seen in the last 20 years is that fertility rates have kept going down in countries that have been rich for a long time. They're already as healthy, wealthy, prosperous as anybody can imagine, and yet their fertility rate just keeps falling. And it's not because child mortality has improved. What on earth is happening?!

This is one of the key reasons why a lot of demographers no longer strictly accept the core version of the modernization hypothesis: assuming that improvements in sanitation and returns on education for material gains explain the drop in fertility is not enough. They don’t explain what has happened in so many countries recently.

To explain the recent drop in fertility in mature economies, you need either recent changes in material conditions that were fairly rapid or you need ideational changes that happened relatively fast, too.

I would argue both of these things have happened. On one side, you do have ongoing ideational changes. People are getting more and more convinced of developmental idealism. They are more and more individualist and secularized.

There's another theory: transcendental communities, explained in detail in the book Birth Control and American Modernity from Trent MacNamara. It argues that people have children to the extent that they see themselves as a member of a transcendental community, an intergenerational project. It might be religion, nation, family line, human species… whatever. But to the extent that you see yourself as a link in a great chain of generations of some community, which is transcendental, you have kids. If you don't see yourself that way, you don't.

Maybe there's been a continuing change in transcendental communities. Religiosity is declining in a lot of countries. We are also seeing increased intergenerational political differences (note from editor: eg, Millennials against Boomers), which might mean there's more intergenerational tension, so fewer people say things like, “Well, grandma really wants a grandbaby.”

Maybe that's what has happened: a weakening of transcendental communities. But I will be honest: while I do think changes in ideas are really in the driver's seat for the historic demographic change, I don't think they usually operate so fast as what we've seen recently.

They do sometimes, but not usually. I gave a few examples like the UK in the 1870s or Quebec in the 1960s. But they're atypical. Usually, when you see rapid change like this, they’re caused by material circumstances. They can be facilitated by ideational changes, but they don’t tend to be the main driver.

My favorite example of this is Greenland in the 1950s or 1970s I believe. Greenland had a fertility of around six kids per woman, and in the space of eight years, it fell to two. What happened!?

Well, the Danish government—which owns Greenland—said: “Greenland is backwards and primitive. We need to fix it. We need to free the Greenlanders from their backwardness of primitiveness.” So they built a small number of giant apartment blocks. They set up tons of health clinics. They brought in tons of colonial administrators. And they basically moved all the local Greenlanders out of their traditional villages into the new towns. This was rapid, possibly not totally voluntary urbanization. If you wanted to get the new health services, the new jobs, the new education, you had to go to the towns. Of course they also tried to eliminate the Greenlandic language and move everything over to Danish.

There were comic mistakes like the apartment buildings that the Danish government built. One of them, Blok P, was so big that it housed 1% of Greenland’s population.

In these apartments, fishing gear didn’t fit in European-sized wardrobes. Coagulated blood clogged up the drainage because fishermen used the only available reasonable place to carve up their catch: the bathtubs. The doors weren't wide enough for people with Greenlandic coats to walk through them. Classic stupid colonialism. It's really awful.

The Greenlanders hated this. It’s what created the Greenlandic independence movement. It was wildly unpopular among Greenlanders, and led to a huge increase in alcoholism and things like that.

What happened is that fertility fell very rapidly. But it wasn't because Greenlanders all suddenly became convinced of developmental idealism. In this case, it was clearly material effects.

TOMAS PUEYO: What specifically in these material conditions led to the drop in fertility?

LYMAN STONE: Several things:

First, the rapid expansion of alcoholism resulted in fewer high-quality male mates. And stable, pair-bonded unions are the most fertile social condition for humans.

Second, they made a rapid expansion of sterilization and IUDs as the preferred form of birth control. You know, it's hard to get people on the pill, you have to maintain a constant supply of drugs up to Greenland… “What if we just offer people tubal ligations and IUDs?” So they were paying people to adopt them, telling them: “This is easy, get this now. And if you want more children in the future, you can just have it reversed.” And then, weirdly, it was really hard to find a doctor to reverse it3.

Third, generally catastrophic social dislocation is bad for fertility. Think of what happened in the Soviet Union after its collapse. Soviet male alcoholism goes through the roof, everybody's out of work. What happened to fertility? It crashed. And it’s not just that families can’t afford babies they want to have. They just want fewer babies. Desired fertility rates plummet.

So what's happened in the last 20 years in a lot of countries? It reminds us of Greenland:

We had the Great Recession. That's a coordinated economic shock that hit everybody all at once.

At the same time, we had major technology shocks around social media that allowed social norms to change rapidly.

At the same time, we had this long standing shift replacing blue collar jobs with skilled work. A lot of legacy, low-skilled work just fell apart during the recession. If you look at enrollment rates in higher education, the number of young people who just extended their time in higher education during the Great Recession is extraordinary.

If you combine all these factors, you see young people had their life course massively interrupted. They experienced a degree of economic instability that many people thought was a thing of the past. They suddenly saw that all these blue collar jobs disappeared: now, you have to get educated to get a job. Suddenly, it took much longer to get a stable job: more internships, more fellowships, more apprenticeships…

Add to that housing insecurity because of the subprime mortgages crisis, housing construction plummeted. Critical housing shortages are growing the cost of housing around the world, and factors into childbearing.

If all these economic issues were happening but our culture said: “You really need to have babies! Babies are central to a good life!” Maybe we would see more political will to fix these problems: “We need to make stable jobs so people can have babies. We need to make good housing!”

That’s not what we see. “You can't have kids? Here's the Instagram ad to go on a nice trip to the wine country. You don't have kids? Maybe that's good for the environment. You don't have kids? Well, you're not childless. You're child-free.”

I’d argue that, in the 20th century, ideation was in the driver’s seat of the drop in fertility, and material circumstances were riding shotgun, in an enabling role.

I think in the last 20 years, we're in a different situation. Recent material circumstances have hammered a whole generation’s experience of family formation. At the same time, we have ideologies stepping up to say: “It's okay, you don't need to fight back against this material change. Just accept it.”

Right now, fertility preferences are still high in almost every country. People want two or more kids, even in countries like Japan and Korea where people only have one kid on average, people say they want 2 to 2.5. My worry is that, over time, these ideational factors will legitimize the adverse material circumstances and lead childbearing desires to drop. That would be dramatic.

Most countries that implement pro-natal policies see birth rates go up by a bit. But when places with low fertility desires like China implement pro-natal policies, they're seeing their fertility rate fall even more.

We are reaching a situation where crappy economic circumstances for young people can turn into a durable trap. And there's a theory around this called low fertility traps that I believe in.

TOMAS PUEYO: If I understand correctly, the low fertility trap is a situation where poor material circumstances lower desired fertility, and if ideas don’t push fertility up but instead adapt to that level of fertility dictated by poor material circumstances, the long-term desire for kids drops. Am I hearing you correctly?

LYMAN STONE: Yes. You can imagine a circumstance where adverse circumstances persist for so long that ideas reset to ratify or legitimate what began as undesired circumstances, right? This is an adaptation story.

And so after that, while you might be able to engineer new circumstances to create new norms, that's very hard to do, and nobody knows how to do that yet.

TOMAS PUEYO: Let's talk about that. What I'm hearing you say is that there are two different aspects of fertility: how many kids you want, and how many kids you have compared to the ones you want.

Ideas impact mostly the first (the number of kids you want) and material conditions impact mostly the second (how many you end up having compared to the ones you wanted).

You’re telling me that we have tools to do both?

How can societies increase the desire to have kids?

How can they help parents have the number of kids they want?

Keep reading with a 7-day free trial

Subscribe to Uncharted Territories to keep reading this post and get 7 days of free access to the full post archives.