Why is Java So Weird?!

Java has a larger population than Russia.

And this is not just a story of “there are plenty of people in Asia”. Java has a bigger population than Japan! Even by Asian standards, Java is just extremely densely populated.

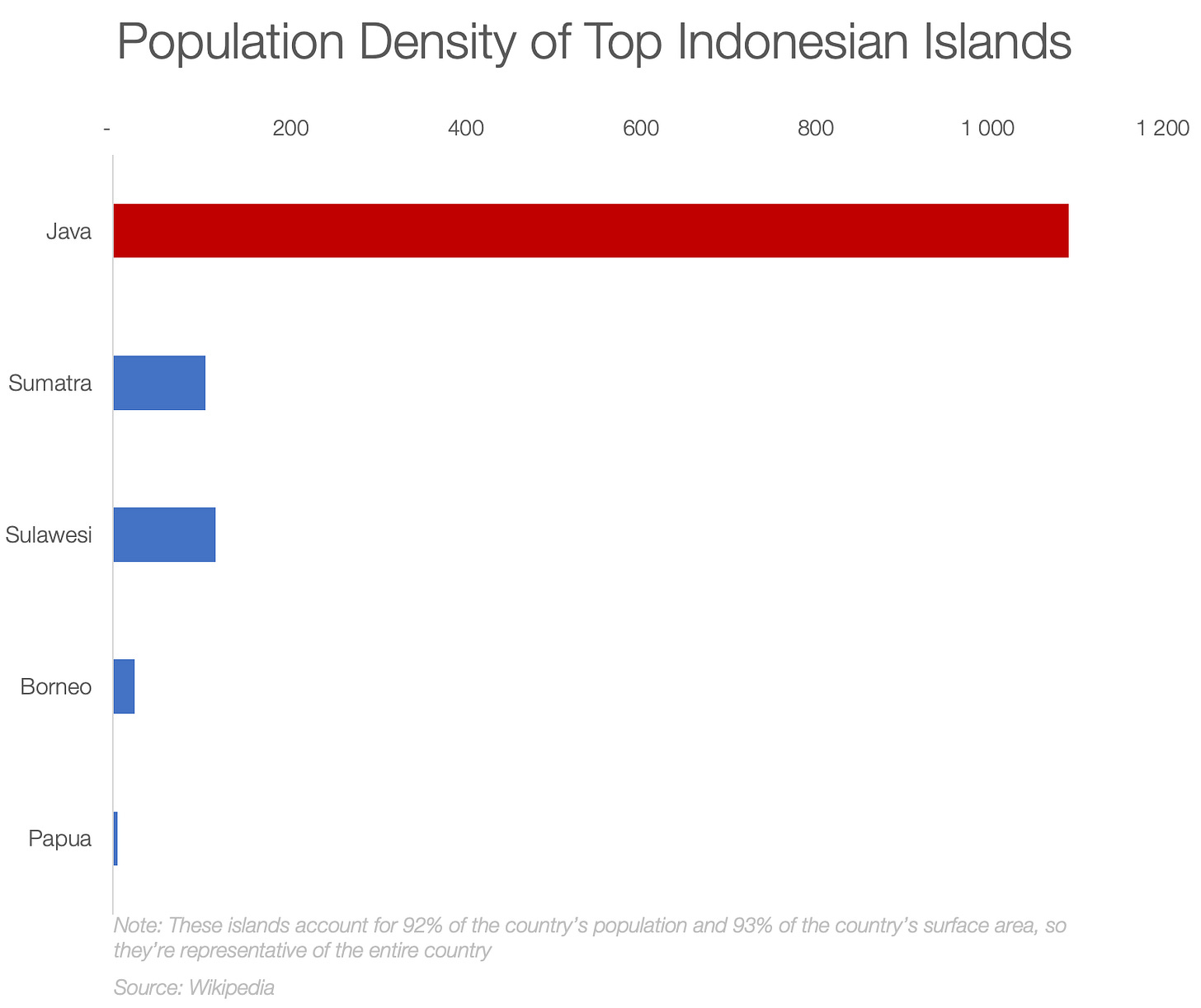

Java’s population density is 1,100 people per square km.

This is 3x the density of Japan or the Philippines, 7x that of China, 30x that of the US. It’s nearly the density of Houston, Texas. For an entire island! With volcanoes!

Even weirder: Its neighboring islands in Indonesia are not that densely populated.

Compared to its big neighboring islands, it’s 8x more densely populated than Sumatra and 30x more than Borneo1!

Why!? What made this island so special?

Is it because it has amazing flatlands? No!

Java is full of volcanoes!

And Sumatra, Borneo, and West Papua all have much larger flat plains!

So basically 55% of Indonesians are crowded in a small volcanic island.

When you zoom in, you can see that the Javanese live everywhere but on the volcanoes!

Compare with Sumatra. Barely any light in comparison.

Sumatra has flat terrain and rivers, while Java has volcanoes, and yet Java is the one island bursting with people. Why?

The Common Explanations

You would imagine there are articles written on the topic readily available on the Internet2. That’s what I thought early on. But all the answers were superficial, none of them were detailed, and most seemed fishy. Here are the more common explanations:

“Java has many volcanoes and… something something fertile land. More food, more people.”

“Java’s location is strategically good, and that gave it a big advantage historically.”

“The Dutch… something something colonial period.”

“Indonesians migrated en masse from other islands to Java.”

And a few more.

So which one is it?

Volcanoes?

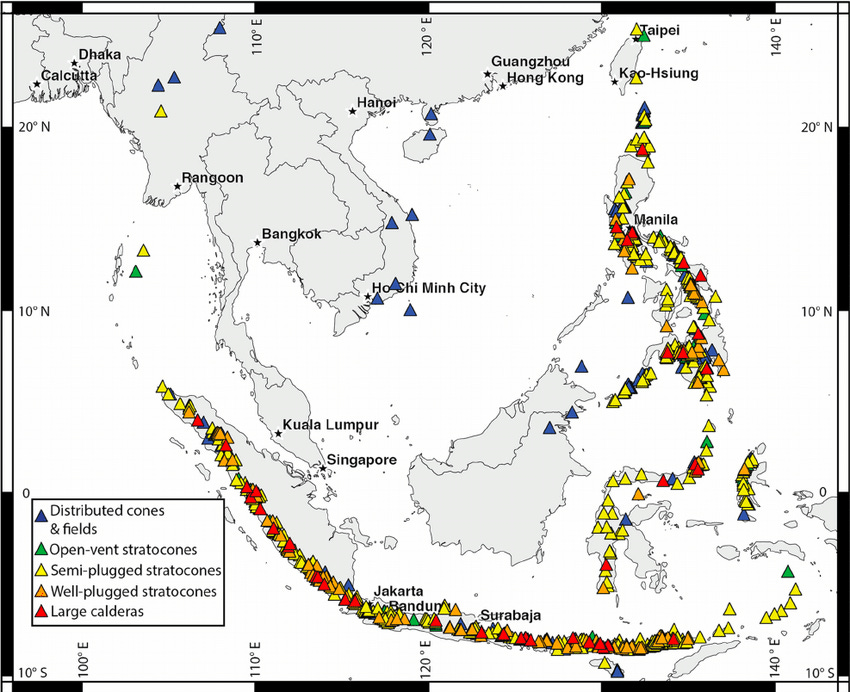

Indonesia has a LOT of volcanoes.

This is because Indonesia belongs to the Ring of Fire, the region around the Pacific Ocean that has lots of tectonic activity that causes volcanoes and earthquakes from New Zealand to Japan, Mexico to Chile.

So this would be the story:

There’s lots of people around the ring of fire: Indonesia, the Philippines, Japan, Mexico…

That’s because volcanic soils are very fertile because they have plenty of minerals, brought by the lava.

This makes sense in theory, but I’ve always had questions about this.

First, you can have fertile terrain, but it’s not like lava is constantly renewing the land. These volcanoes are active, but they’re not covering the soil every few years with a new layer of lava. They erupt every few hundreds, thousands, or millions of years, and when they do, they don’t cover the regions where they are. Wouldn’t intensive agriculture exhaust them, the way farmers have to fallow ground after some harvests to let it build up its nutrients again?

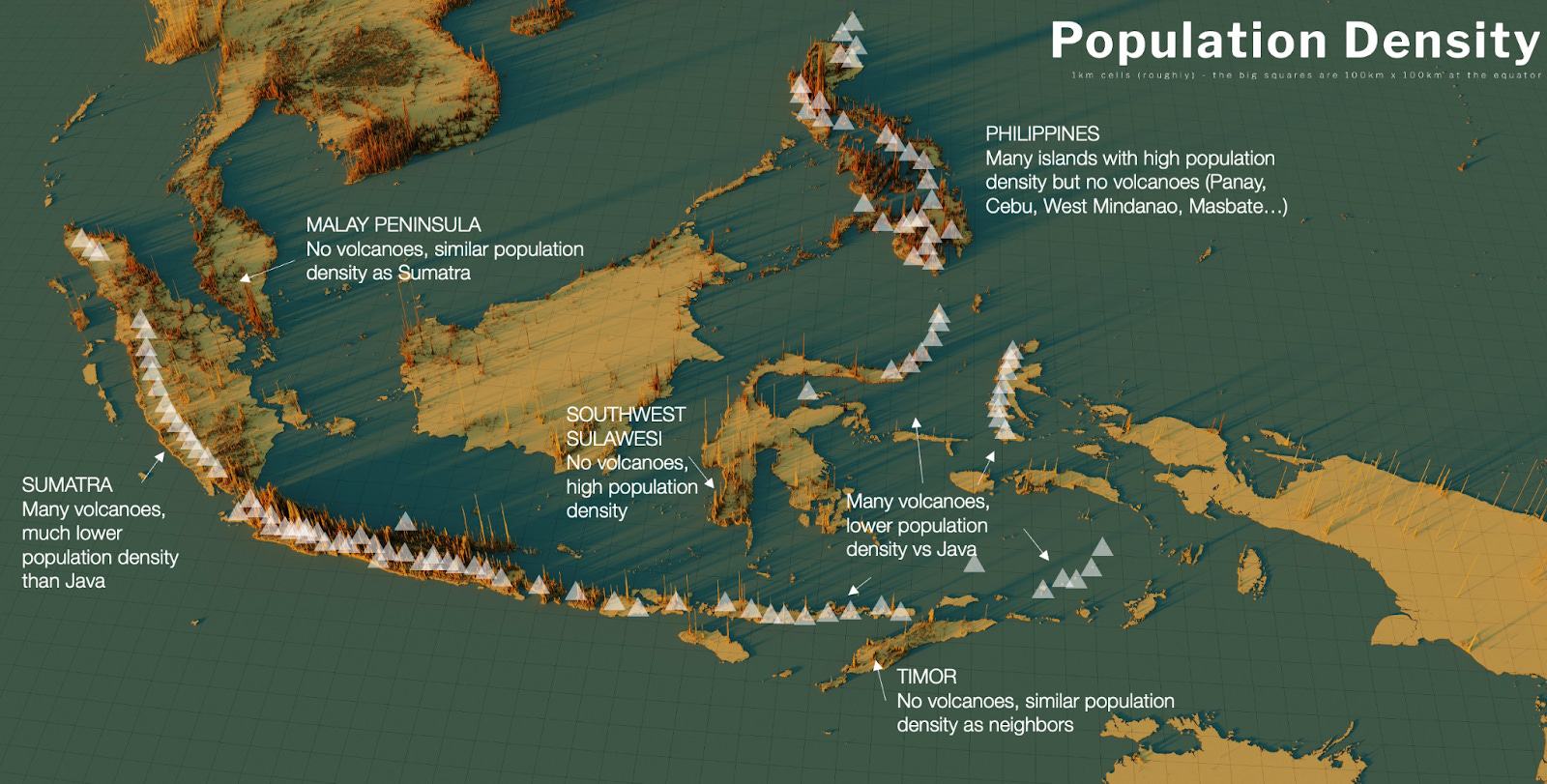

More importantly, if this volcano thing were true, shouldn’t all the volcanic areas be fertile and sustain a big population? We’ve seen this isn’t true: Yes, Java, the Philippines, and Japan have plenty of volcanoes and big populations. But the Indonesian islands of Sumatra and the north of Sulawesi also have plenty of volcanoes, and have smaller populations. Same for Papua New Guinea and New Zealand. Let’s overlap the population density map we had before with the volcanoes map:

What you see is that the volcano theory probably has something to it, but it can’t be the entire story. There are too many places where it doesn’t fit!

Maybe the humans have had a big impact too?

Human Footprint?

Is Java on a key trading route?

Trade

Not compared to the much more important Sumatra, which sits on one of the most important shipping routes in the world, the Strait of Malacca.

Singapore sits at the pointy southern end of Malaysia, and sees all the traffic passing there, while the island of Sumatra, on the Indonesian side, sees very little of it.

So trade has not translated into a big population. Is there a historic reason why Java is so populous? You’d imagine that it has a longer history of civilization than other lands in the region to justify this massive population, but that’s not the case.

An Accelerated History of Indonesia

The Srivijaya Empire was the first to pop up, based in Sumatra, not Java.

But their center of power was on Sumatra, not Java.

The Srivijaya would later spread to other islands, including Java around the year 1000.

Over time, Java would grow in importance. The Javanese Singhasari emerged from there and expanded all the way to the Asian Continent.

They would later be succeeded by the Majapahit around 1300.

No local empires appeared after that. Local kingdoms would fight each other for hegemony, with an increasing presence of Muslim kingdoms on the coasts, through the influence of trade.

While Muslim influence grew on the west of the archipelago, European influence started increasing in the east. By the mid-1500s, the Portuguese popped in, but as a small country focused on spices, it didn’t try to conquer much more than what was necessary to maximize trade. Spices were more common in the smaller islands in the middle of Indonesia, called the Moluccas, now Maluku islands (between Sulawesi, Timor, and New Guinea).

As other European countries learned about Portugal’s spices, they got into the business too. At that time, the local kingdoms were too strong for a set of trading ships coming from far-flung European countries to be easily subdued.

Over the following decades, the Netherlands would slowly conquer the whole region, fighting with local kingdoms, and on the European side first with the Portuguese, and then with the British.

Until it gained its independence in the wake of World War II.

So Java is not on the most important trade route of the neighborhood, and it got settled late. It didn’t have the most valuable spices. The position of the island is not much more strategically relevant than that of Sumatra, Borneo, or Sulawesi. This lack of uniquely valuable strategic position is still true today, which is why the government recently decided to move the capital to Borneo. It can’t be because of some strategic position or historic reason from ancient times. What about migrations? Was there a policy at some point to push people into Java? No, the opposite.

The Transmigration Program

Since the early 1800s, there have been policies to resettle Javanese people on other islands. They were started by the Dutch government, but continue to this day.

About 25% of Sumatra’s population settled there as a result of this policy3! Immigrants from Java also account for 16% of Kalimantan’s population (reminder: this is the Indonesian side of the Borneo island).

Migrations didn’t push Java to be populous. If anything, they had the opposite effect. Maybe we can find other explanations by looking at comparative population growths.

Javanese vs Indonesian Population

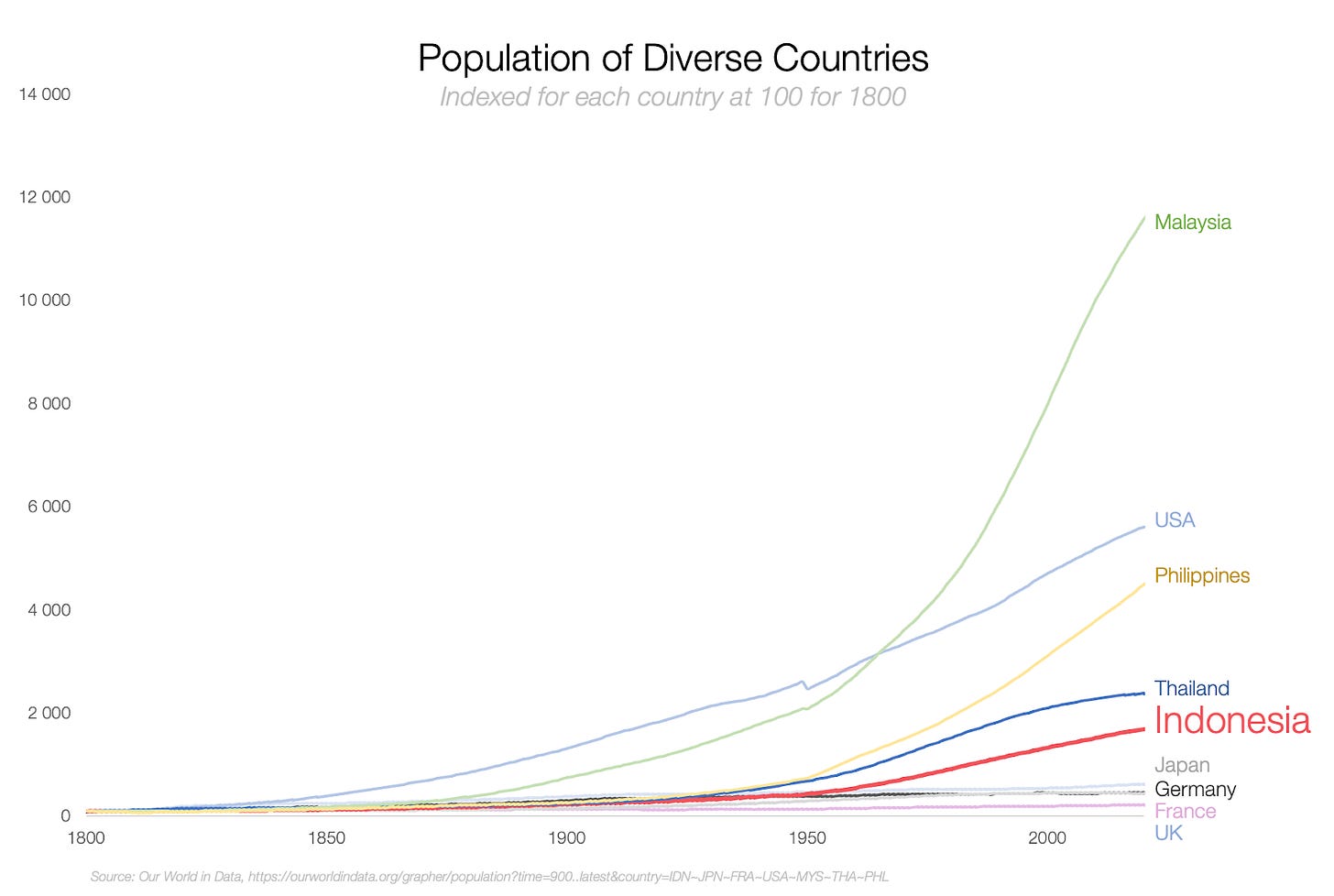

Before 1800, Indonesia’s population was smaller than those of countries like France, Germany, or Japan, and about the same as in the UK. Its growth then accelerated dramatically and passed them. Out of the sample on the graph above, only the US was smaller than Indonesia and became bigger—mainly due to European immigration. So did Indonesia grow uniquely fast starting in the 1800? Not really.

The populations of neighbors like Malaysia, Thailand, or the Philippines have grown much faster than Indonesia’s since 1800. Based on these two graphs, we can conclude that:

Indonesia was more populous than its neighbors in 1800.

The population of the entire region then grew fast. Indonesia did not stand out.

Is this also true of all of Indonesia’s islands? No!

Java was already populous in 1800, and only grew more so during that century, increasing its share of the Indonesian population. This means that Java was growing faster than the whole of Indonesia, so it was probably growing as fast as other fast-growing Southeast Asian countries.

This means that Java was more populous than other Indonesian islands before 1800, and kept growing faster than them after 1800, reaching 80% of all the Indonesian population at the end of the 1900s. Despite transmigration, Java’s population kept growing. Whatever caused Java to be populous is a force that was true before 1800 and has kept going to this day

Our biggest conundrum is still intact: Why is Java so much more populous than Sumatra?

It can’t only be the volcanoes: Both islands have approximately the same amount.

It can’t be for historic reasons: Sumatra is better positioned for global trade, and has a longer history. Java’s strategic position is not much better within Indonesia, compared to Sumatra, Sulawesi, Borneo, or other smaller islands.

It can’t be migration, because if anything, people were pushed out of Java and into Sumatra.

If Java has something going on for it, it must be such a strong force that it overpowers everything else. Since people are produced by food, let’s go back to that: What could cause Java’s food production to be so much higher than Sumatra’s?

Food

The only way you can sustain so many people in such a small area and against history is if you have some massive advantage to produce food locally. Indeed, Java is a food production machine. Most of the island is either volcanoes, cities, or farmland.

It’s mostly rice, which is good, because rice is one of the most calorie-intensive staples there is, together with corn. And since rice needs many people to harvest it, it makes sense to have many children per household, since they can be fed and help in the harvest.

What is the production in other parts of Indonesia?

Ah.

There’s a heavy overlap between rice-producing areas and population densities across islands, and it doesn’t look like volcanoes are the only thing going on here.

Java produces 75% of Indonesia’s rice (for 57% of the population). Sumatra only produces 15%, and Sulawesi 10%4. Why is there no more rice in Sumatra? It must be linked to the fertility of the fields, right?

My experience in agriculture is close to zero. Undeterred, I spent an inordinate amount of time looking at maps of soil fertility in Indonesia, so you don’t have to. I then compared the fertility of different soils, which was quite hard since I couldn’t find readily available data. So I asked ChatGPT to give me a hand. The results match the intuition, but given my shallow experience, my confidence on the section below is medium-low.

Depending on the map of Indonesian soils you look at, you get different terms for the soil. But their fertility is consistent across maps:

In Java, nearly all the soil is very fertile. A good chunk of it is andosols, which comes from the volcanoes, which means it’s young soil that hasn’t lost its nutrients through millions of years of leaching. That means it can support lots of crops for a long time. It also has luvisols and nitosols, both of which are fertile5.

Meanwhile, soil in Borneo is mostly acrisol6, which is not fertile at all. It corresponds to the red areas. You also find oxisols, similarly not fertile.

In Sumatra, you find a lot of acrisols too in red. There are also oxisols, not fertile at all. The purple part is dystric histosols, which is constantly wet and full of peat, and not fertile at all either. Interestingly, the main city of Medan is placed on andosols. Outside of Medan, the highest population density on the island can generally be found near the volcanic area, on the west coast.

What we’re finding is that, indeed, the volcanic soil is among the best in the world for agriculture. What I didn’t realize early when researching this early on is that it’s so good that it can sustain over a century of high agricultural production, feeding literally over a hundred million people now, and remain fertile. Not only that, but also it’s not just lava that makes it productive. Ash does that too. And since there’s a lot of ash falling on Java all the time, maybe this helps maintain the fertility.

In Sumatra, the volcanic regions are also andosols, and also reasonably fertile, with a sizable population. But Sumatra has a lot of land that is not fertile at all—those acrisols, utisols, and oxisols. Why?

First, let’s understand the volcano part.

There are lots of tectonic plates pushing against each other in the region.

In Java and Sumatra, the oceanic plate is subduing below the islands, creating volcanoes and earthquakes, but also mountains.

In Java, nearly all mountains are volcanoes, but not in Sumatra. But mountains are not as good as volcanoes for soil fertility, so the Sumatran mountain range is not as fertile as the Javanese volcanoes.

More importantly, the rest of the Sumatra island is not volcanic! And neither is Borneo. Both are in the middle of the tectonic plate. Borneo doesn’t have active volcanoes. Its mountain range was formed hundreds of millions of years ago, which means the soil has been eroded and leached of nutrients for a long time.

And Sumatra and Borneo are both on the equator, which creates a very special type of environment. Lots of sun is good for plants. The heat also creates evaporation, which then translates into rain. A lot of it. It would leach the soil of its nutrients if it weren’t for the fact that plants and trees grow so fast. So what happens is that plants grow, die, and before they can convert into soil, their nutrients are consumed by other plants, or washed away. In any case, no nutrients are fixed on the land, and as a result it’s quite poor for agriculture. It works for plantations that are based on trees—and this is why Borneo and Sumatra together produce more than half of all the palm oil in the world: Trees can grow there and avoid erosion, but you can’t harvest full plants.

And the waters are shallow between Java, Sumatra, and Borneo, which means that in lowland areas, water just never leaves, or even comes from the sea. This happens in the eastern part of Sumatra, which makes it impossible for crops to be grown unless the regions are drained.

Fun fact: The land between these islands is so flat that just a few tens of thousands of years ago, as Homo Sapiens were spreading around the world, Java, Borneo, and Sumatra were all part of the same landmass, Sundaland.

Takeaways

So this is why Java is one of the most densely populated places in the world, while neighboring Sumatra and Borneo have much smaller populations:

Java and Sumatra are on the border of a tectonic plate. This means a lot of volcanoes.

Java

But Java has more volcanoes and fewer other types of mountains. This means lots of very fertile land that can sustain a lot of agriculture for a long period of time.

The Javanese grow lots of rice with that fertile land, which feeds its huge population.

The Javenese also need big families to tend to the rice fields, so natality has always been encouraged. Fertility of land have bred fertility of humans.

Sumatra

Sumatra has a decent amount of volcanoes, which have produced its most fertile soils that support its population.

But Sumatra also has many more mountains that aren’t volcanoes, whereas Java is nearly exclusively volcanoes. These mountains haven’t generated fertile land around them.

And the rest of the land is not fertile at all.

Part of the lack of fertility is because it was formed hundreds of millions of years ago, and its nutrients have leached since, without being very replenished by its volcanoes, which are less active.

Part of it is because it lies squarely on the equator, which means it has a massive amount of rain that continuously leaches any remaining nutrients, a process that agriculture only accelerates.

Part of it is because its lowlands are drowned in water.

Borneo

Meanwhile, the island of Borneo has all the problems of Sumatra and none of its assets:

It was formed hundreds of millions of years ago.

It has a big, old mountain range in the middle with no volcanoes.

Equatorial rains leach its soil.

As a result, it doesn’t allow for much agriculture on its land, except for some tropical plantations7.

The proper name is Kalimantan, which is the Indonesian side of Borneo. From now on, I’ll use the name Kalimantan, unless I specify otherwise, for clarity.

Sometimes I use ChatGPT to find some obscure concepts that are hard to put together with Google, but here ChatGPT was awfully wrong. I guess there is too much speculation and not enough facts on the Internet to have trained ChatGPT better.

15.5M Sumatrans are migrants or descendants of migrants from Java, out of a population of about 60M in Sumatra.

Borneo doesn’t even make it to the figures.

Depending on the source, you can also find inceptisols and mollisols. All of them are very fertile, and all of them seem to be the result of the volcanic activity in the area, combined with other geological effects.

It does have mining though, and its position is strategic enough that Indonesia has decided to move the capital there.

Tomas - Boy do I have the book for you. It turns out that none other than Clifford Geertz wrote a whole book (one of his most influential in fact) on exactly this subject. Like, literally exactly this subject. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Agricultural_Involution

Basically you are on the right track that it has to do with the social demography of rice production in that specific environment. You can go grow rice in a labor extensive (slash and burn) or labor intensive way (paddy based). Java and Bali are the most populated regions of Indonesia and they both are organized around sawah, or paddy based production. It turns out that rice responds to manual labor better than any other cereal crop. In other words, rice yields go up with the intensity of labor inputs, not literally infinitely but it can seem that way (think about people standing in a paddy transferring individual shoots of rice into the ground at very careful intervals and then tending that tiny paddy obsessively over months). Over time, as the farms get subdivided down through family succession the pressure on individual units of land to produce enough rice to sustain a nuclear family goes up. The response is to have more kids so that you can pour more labor into the paddy so that you can squeeze more rice out of it. More kids means more subdivision through succession, and so on and so on over many many generations.

As an Indonesian that live in Java Island. I approve this article.👍

Adding to that, Javanese people have a very polite character (not in japanese polite sense). Helping each other even stranger. If you go to java and ran out of money. You still going to survive because their hospitality.