Why Japan Succeeds Despite Stagnation

I don’t usually do guest posts, but today is an exception. Maxwell Tabarrok is an economics researcher at Dartmouth College and author of the substack Maximum Progress. He proposed this article about the end of Japan’s stagnation, and I found it super interesting, especially as I am just studying Japan and the economic miracles of this country, Taiwan, South Korea, and China. Japan’s economy is also important to understand, as it’s the canary in the coal mine of low fertility rates. So Max and I worked together to make his article fully Uncharted Territories-like. I hope you enjoy it! I’m slightly late on articles this week, will catch up next week.

For more than three decades, Japan has endured near complete economic stagnation. Since 2000, Japan’s total output has grown by only $200B.

That’s less additional output than Nigeria, Pakistan, and Chile, even though they all started from much lower bases, and only around a fifth of South Korea’s growth over the same period.

But despite severe economic stagnation, Japan is still a desirable place to live and work. The major costs of living, like housing, energy, and transportation are not particularly expensive compared to other highly-developed countries. Infrastructure in Japan is clean, functional, and regularly expanded. There is very little crime or disorder, and almost zero open drug use or homelessness. Compared to a peer country like Britain, whose economic stagnation over the past 30 years has been less severe, Japan seems to enjoy a higher quality of life. In short:

What explains Japan’s lost decades? And how has the country still managed to maintain such a high quality of life?

Facts of Japan’s Stagnation

Before explaining why so many aspects of life in Japan succeed despite its economic stagnation, we ought to make sure that the stagnation is real.

Japan’s total GDP grew at less than 0.25% per year from 2000-2019. US GDP grew nearly 10 times faster over the same period.

Japan isn’t doing better on a per capita basis. Its GDP per capita growth is still sluggish compared to peer nations, so the picture isn’t much different than what’s shown in its total GDP trend.

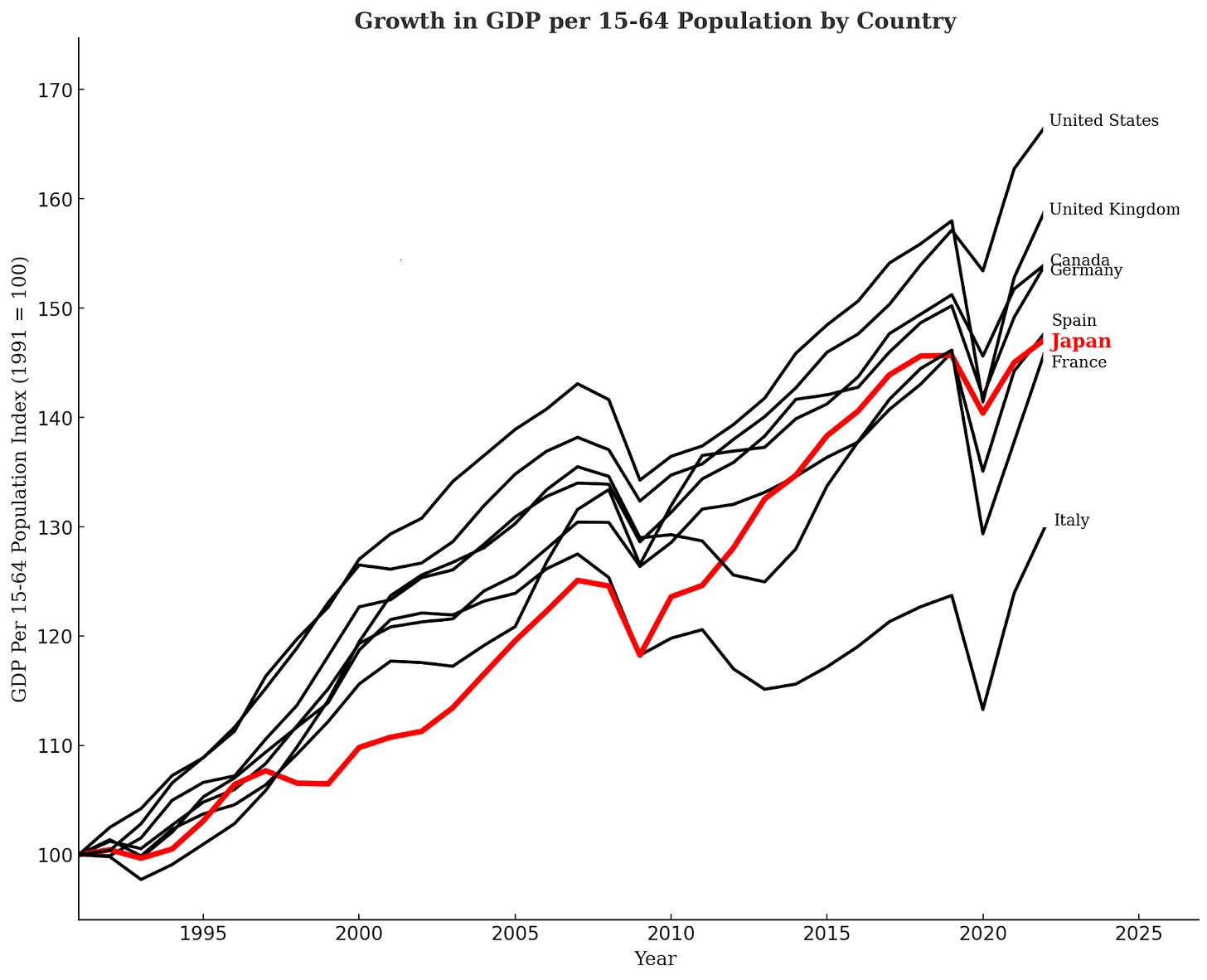

What about productivity? Per capita GDP is usually highly correlated with productivity, but it’s a particularly biased measure in this case. Much of Japan’s population is too old to be in the workforce, so dividing GDP by the entire population counts millions of people as labor input when they don’t actually work. If you instead compare Japan’s GDP growth per working age adult to other nations, it doesn’t look quite as bad.

By this metric, Japan still has lower growth than everyone except France and Italy, but it’s only near the bottom of a tight pack, rather than an outlier far behind anyone else. So is Japan’s stagnation a statistical illusion masking what is actually reasonable performance?

No, the stagnation is real.

First, even by the adjusted metrics Japan’s growth is worryingly slow. It does the best relative to the US by GDP per working-age adult, but it’s still barely 6th out of the 8 countries graphed. The countries that Japan beats or matches: Italy, Spain, and France, are not examples of healthy, high growth economies. Compared to Japan’s neighbors like South Korea, Taiwan, China, Singapore, Malaysia, or Vietnam, its growth rate is a low outlier. Casting Japan as similar to Western European economies is evidence for the severity of its stagnation.

Second, and more importantly, is that total GDP matters! Japan needs a high level of total GDP to provide for its dependent population as it balloons compared to the working few. Japan needs to produce enough to pay for trillions of dollars of debt. Japan also needs to produce enough to defend itself against potential threats like China and North Korea. Productivity alone isn’t enough to meet these challenges; total output is what matters, and Japan is extraordinarily stagnant by that metric.

Causes of Japan’s Stagnation

Japan spent over a century on the frontier of global economic growth. What caused Japan’s growth to crash in the late 90s and never recover?

Demographics

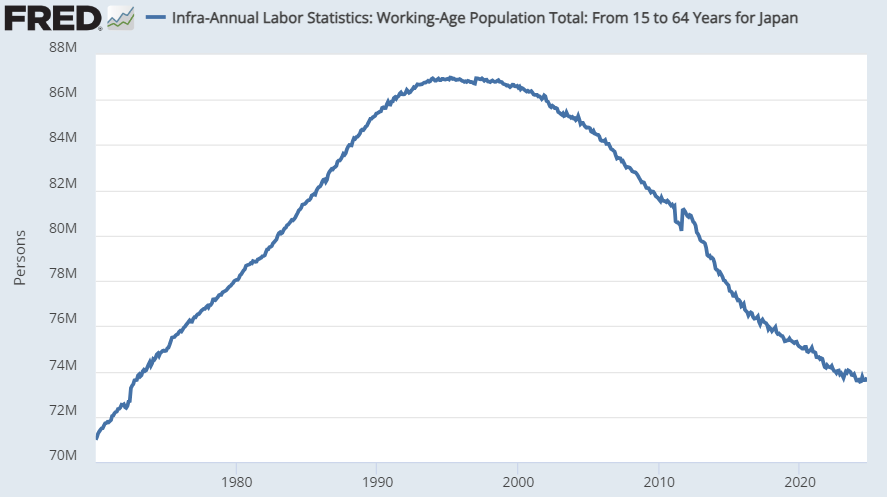

Japan’s working age population is now the lowest it has been since 1973. The 65+ population in Japan is more than half the size of the working-age population and more than double the size of the under-15s. Japan has the 13th lowest fertility rate out of 204 countries, and the 6th lowest if you don’t count city-states. It’s difficult to grow economic output when supply of labor, the most important input, is shrinking.

Japan’s demographics drag down its productivity growth, too. Productivity is ultimately a result of new technologies and ideas which come from people. Fewer people means fewer ideas in total, but it also means smaller agglomeration benefits, network effects, and returns to scale, which makes each member of the smaller population less innovative, too. Japan’s patent rate per working age person peaked in 2000, a few years after its total patent numbers and working age population peaked in 1995.

Japan’s demographics overshadow and underpin all the other explanations for its stagnation. If Japan’s working age population had stayed at its 1997 peak and productivity growth had been the same, its GDP would be 20% larger than it is today. The true cost of population decline is even larger than this because of its effects on innovation and productivity growth.

Zombie Firms

There is more to Japan’s stagnation than demographics. The challenges posed by falling population are magnified by a debt-funded resistance to creative destruction. This has kept Japan entrenched in industries where it lacks comparative advantage while stifling the emergence of new, dynamic sectors to replace uncompetitive ones.

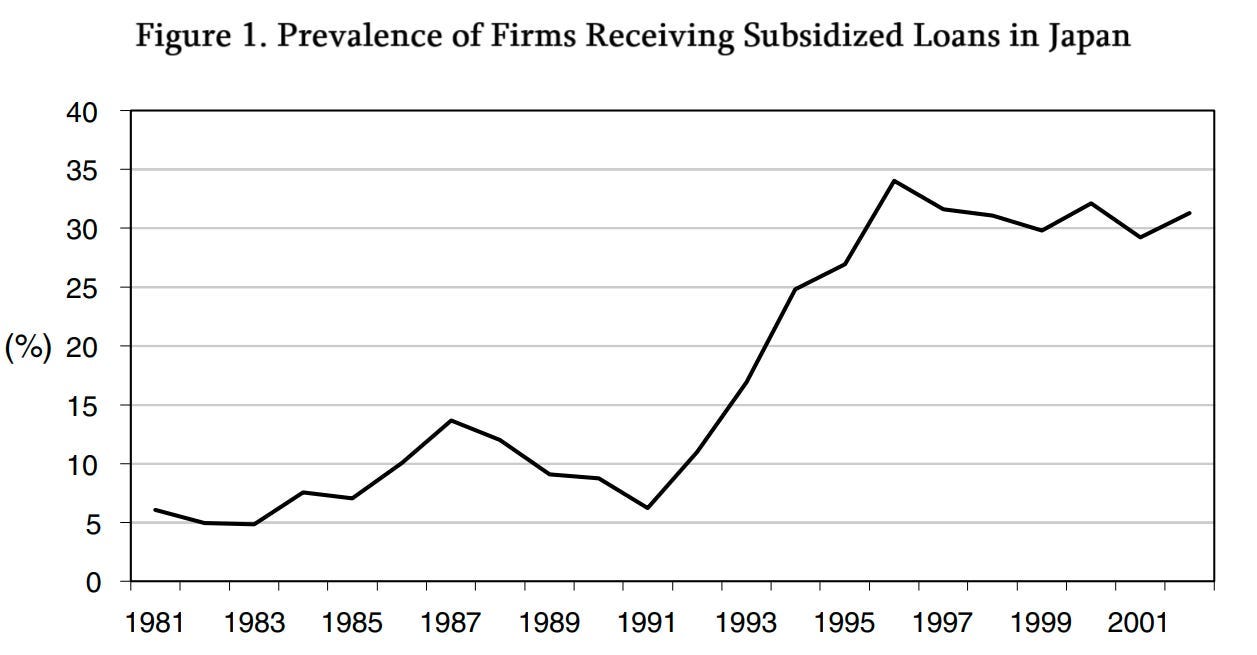

A key mechanism sustaining these declining firms is heavily subsidized debt. The practice of extending loans to failing companies is known as "zombie lending."

When a borrower fails to pay interest on a loan or goes bankrupt, their bank must classify the loan as “non-performing.” This means the bank can no longer count the loan value as an asset, and they have to set aside cash to at least partially replace the value of the non-performing loan. That leaves less cash available to loan out and thus less profit for the bank.

Alternatively, the bank can offer more money to the ailing borrower which the borrower uses to continue making interest payments on their loans. Thus, the loan remains as an “asset” on the bank’s balance sheet, even though everyone involved understands that there is little chance the loan will ever be repaid. This creative bookkeeping allows the bank to accept more deposits and loan them out to other, hopefully more profitable, ventures. A combination of explicit regulations, regulatory forbearance, and implicit social pressures among the tight-knit group of Japanese business, banking, and government leaders promote this practice of zombie lending.

The percentage of “zombie firms” i.e those firms subsisting purely on subsidized debt increased from around 7% in 1990 to more than 30% in 1996 and has stayed elevated since, coinciding with the beginning of Japan’s lost decades. For comparison, a similar measure of zombie firms in the US counted around 8% of firms as zombies in 2019. One important difference, however, is that US zombie firms tend to go out of business within 5 years. Japanese zombie firms, on the other hand, often last for decades and maintain high employment and market share.

Industries with more zombies have less churn of resources between firms; exactly the opposite of what is optimal in an industry with lots of unproductive firms. Usually, in an industry with unproductive competition, a highly productive firm will expand rapidly, but when the unproductive competing firms are subsidized by cheap debt, healthy firms grow more slowly and are more likely to exit the market altogether.

Zombie lending has lowered aggregate Japanese productivity growth by at least 30-50%. Productivity growth can be decomposed into four parts based on where it happens: Within firms, reallocation of resources between low and high productivity firms, entry of new firms, and exit of existing ones. Throughout Japan’s lost decades, the exit portion of productivity growth has been highly negative. That means that the lowest productivity firms are staying in business, and the highest productivity firms are leaving. This is a tell-tale sign of a lack of creative destruction due to zombie lending. Resources should be flowing from the lowest productivity firms to the newer, high productivity ones, but in Japan’s system, ailing firms get the most subsidies so they are able to retain workers and capital even when they make next to no revenue.

The negative exit effect decreased Japan’s annual manufacturing productivity growth by a full percentage point between 2000-2005, meaning productivity growth would have doubled without it and grown even more if firm exit had a positive effect as in most healthy economies. The other major productivity slowdown from shrinking “within-firm” growth is more directly related to Japan’s aging and less innovative population. Zombie lending also contributes to falling within-firm productivity. It prevents the death of stagnant firms and allows their innovation-stifling practices to ossify and spread.

To summarize, Japan's stagnation comes from two forces: a shrinking population, which means fewer workers to produce economic output and fewer inventors to raise productivity; and "zombie firms," kept alive by subsidized loans, which prevent creative destruction and drag down productivity growth across the economy.

Successes Despite Stagnation

Japan’s economic stagnation is among the most severe in the world, especially when compared to its world-beating growth in previous decades. Yet, Japan is still a great place to live and work. How does Japan retain these good qualities despite its poor economic performance?

Japan Gets Housing Right

A major source of economic pessimism in Western countries is high housing costs. These countries have throttled housing and most other physical construction activities with environmental proceduralism and highly localized zoning enforcement. This has led to major cities like San Francisco permitting less than 150 new units a year in a city of 800,000 people.

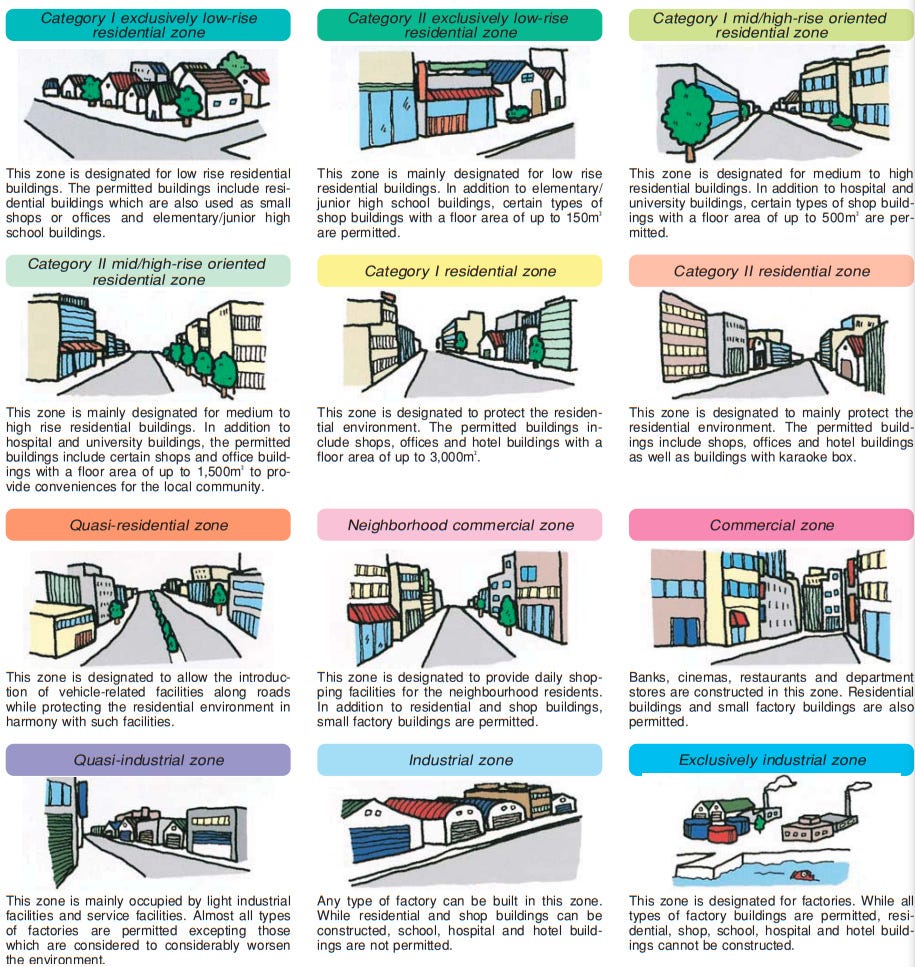

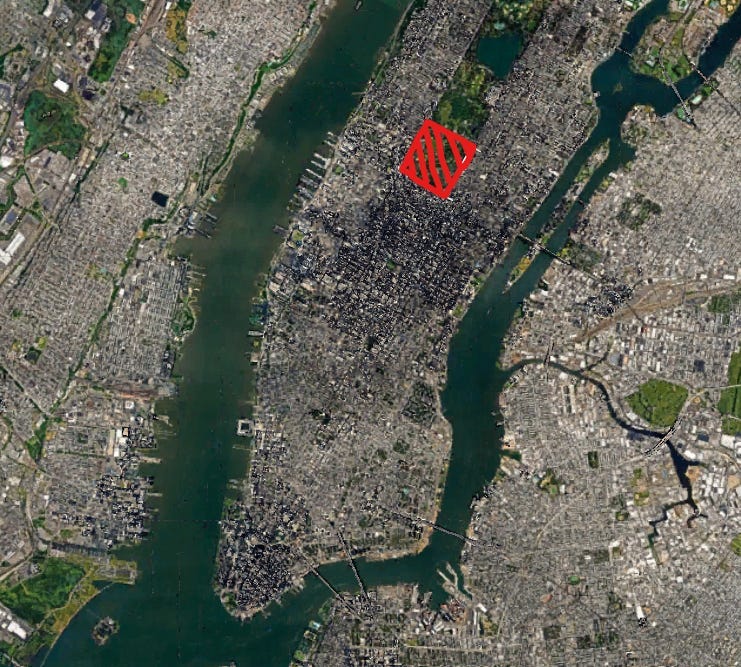

Japan’s zoning code is set at the national level and therefore tends to be much less restrictive than the local zoning codes found in the West. Its national system lays out just 12 inclusive zones, which means the permitted building types carry over as you move up the categories, allowing mixed-use development by default. This compares favorably to zoning codes in the US which often have multiple dozens of exclusive land use categories. Even the most restrictive category in Japan’s system, shown in the top left (below), allows people to run small shops and offices out of their homes. There are floor-area-ratio limits and setbacks, but they are modest, and there is no distinction between single and multi-family housing units within these limits.

For environmental permitting, Japan mostly relies on explicit standards for environmental impact, rather than a lengthy permitting process where applicants must write detailed reports about possible alternatives and mitigation measures under threat of lawsuit, as in the US. Japan does have a copy-cat National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) procedural environmental law that was enacted in 1997, but it has two important differences that prevent its evolution into the procedural morass seen in other countries.

First is explicit numerical standards for which projects must go through the impact statement process, rather than the hand-waving ambiguities of NEPA. These standards generally only include large infrastructure projects like a port extension exceeding 300 hectares. Some residential projects are covered, but only those which exceed 75 hectares in area. Only 854 environmental impact assessments have been started in Japan since the act passed, and there have been zero for residential construction projects.

Second, the completed environmental assessments are harder to sue over than in Western countries. Plaintiffs need to have a personal and legally protected injury to have standing, rather than a generalized concern for the environment as in the US. Plus, the greater specificity of when the law applies and a court that has a much more deferential attitude towards agency determinations means the lawsuits are harder to win.

Permissive national zoning and an absence of environmental proceduralism leads to Japan having the highest rate of housing construction and the lowest home price to income ratio in the OECD.

Expensive and exclusionary housing can make the most prosperous and beautiful city on earth lose 10% of its population and conversely, abundant housing goes a long way to making a place feel prosperous, even when incomes are stagnant.

Capital and Culture

Japan has two other advantages which offset the bad vibes and welfare costs that one might expect from a stagnant economy.

The first is downstream of its demographic decline and its well-designed building regulations. Japan has a rising capital to labor ratio. Essentially, this means that each worker in its economy has access to more infrastructure and machines than in the past. This is because Japan has lots of durable physical capital but a shrinking population, and it probably explains a good portion of why its per-worker productivity growth has managed to stay high relative to its sluggish growth in GDP overall. In fact, standard economic growth models predict that with an exponentially declining population, living standards stagnate to a constant level because the loss of income caused by slower technological progress tends to be offset by this rising capital to labor ratio.

Japan’s second advantage is more difficult to quantify but is likely as important as the previous factors for offsetting the costs of stagnation: Japan has high levels of trustworthiness, cleanliness, order, and peace. Japan has extraordinarily low rates of crime of all types, drug use, and homelessness. Its trains are always quiet, clean, and on time.

Most crime is committed by young men, so Japan’s low crime rate is partly explained by its older age structure. For example, in 2019 Germany had four times Japan’s overall homicide rate but after adjusting for age differences it’s still twice as large.

Japan’s social order is incredibly valuable. The annual cost of crime in the United States is around $5 trillion dollars which is 18% of GDP. Higher crime rates would threaten the high-density urbanism which makes Japanese cities so affordable and desirable.

Japan’s exceptionally orderly and safe public spheres are matched only by other countries in East Asia, so the persistence of its social order is aided by low migration rates, and especially low rates from non-East-Asian countries. Higher rates of immigration could help with many of Japan’s challenges, especially its shrinking working-age population. And increasing immigration from China and Korea doesn’t pose a serious threat to its cultural norms, though these countries have their own severe demographic problems on the horizon. But as the experience of Western European nations show, it is possible to have high immigration rates alongside low growth. Under these conditions, zero-sum thinking is both more common and more accurate, and backlash against immigration is intensified. Japan should increase its immigration rates to offset the severe consequences of demographic decline, but this immigration increase needs to be paired with rapid economic growth and ideally growth of the Japanese population so as not to threaten its valuable cultural norms.

Can Japan Reverse Course?

Japan’s highest priority should be reversing demographic collapse. Directly addressing birth rates with subsidies is a simple first step. Given Japan’s fiscal obligations to its growing elderly population, each member of future generations must contribute 50 million yen to the government on net, or around $300,000.1 Thus, the government should be willing to pay up to this amount to induce new births, and perhaps more, since this fiscal accounting does not account for the extra economic growth that extra population would cause.

The success record of fertility payments is mixed but weakly positive, though no fertility payments in the same order of magnitude as what Japan can afford have been tried. The risk of wasting money with the world’s largest fertility payments are small compared to the risks that Japan faces if its demographic decline continues.

In addition to economic incentives, cultural initiatives to promote family life are important. It’s difficult for governments to push culture in desired directions, but it’s worth trying to explicitly celebrate fertility. Other interventions in between culture and economics can be more decentralized. Put free daycares in universities so that young people have exposure to parenting and the resources to try it without removing themselves from the social circles and career paths of their friends and role models.

Fertility is Japan’s biggest challenge, but it's not the only one. Japan needs to address its lending policies, allow more creative destruction and more startup formation. The practice of banks holding onto non-performing loans should be discouraged by stricter accounting standards that force recognition of bad debt. This would free up capital and human talent currently trapped in unproductive zombie firms, allowing resources to flow to more innovative enterprises.

Japan’s success in the face of demographic collapse and economic stagnation is one way of proving the importance of housing policy and social order. Getting those things right, as Japan has, creates a foundation strong enough to withstand three decades of zero growth. But even the strongest foundation will crack under enough weight - and the combined mass of demographic collapse and zombified capital misallocation grows heavier by the year. If Japan can turn these trends around, its other advantages would do more than simply offset stagnation — they would create rapid growth and widespread prosperity for decades to come.

I hope you enjoyed the article. Let me know what you think! If you want to read more about economics, science, policy, or AI, you can subscribe to Maximum Progress here or follow Maxwell on X.

The next article, for premium customers, will be about why Japan has the zombie lending policies today, why it’s a direct result of its past success, how that is similar to South Korea, Taiwan, and China, and why Southeast Asian countries didn’t follow the same path.

Note from Tomas Pueyo: There is evidence that on average inducing one birth costs about the same as GDP per capita, which in Japan is about $34k, so Japan could definitely boost fertility with big spending.

I wonder: The whole article reads well-ish untill we reach the dogmatic part "Can Japan Reverse Course?" - why should they reverse course? Why is the demographic change such a apocalyptic scenario? They can - if they want to - go into more debt to fince this transition. The bank of japan and the yen has quite some autonomy here.

Second Point: I would even argue the housing in japan is so cheap because japan is losing roughly 800k citizens a year. Yes over-regulation seems to play a role, but for example the author completely misses the point that there is quite a high inheritance tax, making investments in housing way less profitable than in the western world. I had read somewhere that houses in Japan are considered an item similar to a car.

Third point: The author argues zombie firms are a bad thing per se. I think this can be argued with - they provide jobs, maybe bullshit jobs, but they keep people employed and these people do not have to rely on social welfare. Is that such a bad thing? One might even argue that such jobs are the future for the western world especially when we will lose jobs to AI, people will value e.g. an excellent customer service as provided in japan.

Finally the author does not really answer why fertility is in decline in japan, it might as well be due to bad conditions to raise a family, spoiling the utopian picture depicted here - i remember vaguely that for quite a while japan had the highest suicide rate in the world because of very demanding work-life culture and very rigid cultural norms.

Great piece Dr. Tabarrok.

One aspect to explore is that all that social order probably owes something to the employment stability you get from refusing to let zombie firms fail. Japanese policy makers think explicitly in these terms: the resistance to tightening lending standards is usually couched in terms of protecting employment. They may be right: the extra economic vitality may not be worth imperilling the secret sauce of an orderly society: predictable and stable career paths for the broad middle class.