Can We Build AI in Space?

This is the only article of the week. The 2nd half is premium.

Elon Musk is betting his companies SpaceX and xAI on space datacenters.

He believes that, in three years’ time, AI companies won’t have access to enough electricity to power their data centers, so only those who move the data centers to space will be able to continue growing their AIs.

The question becomes: Can you build working datacenters in space at a reasonable price?

As I ran the numbers, I realized that Musk is on to something: Datacenters in space are already in the ballpark of costs of land-based ones, and might soon be cheaper! This article will explain why.

In the process of writing it, I studied dozens of sources, including many space datacenter reports. I also wrote a tweet to gather feedback from the community—which Musk responded to. That said, as it’s my first foray into space datacenters, I’m still guaranteed to have made mistakes; I just don’t know which ones. However, it doesn’t look like they would change the conclusions. Please point out mistakes if you find them.

What Does a Space Datacenter Look Like?

At its core, a datacenter on land is pretty simple:

The GPUs1

Some other IT stuff, like memory, radiators to cool the system, connectors, etc.

A source of electricity. If you want your data center to be independent from the grid, you’ll want:

Solar panels to convert light into electricity

Batteries to store the excess electricity from the solar panels during the day and power the datacenters at night

If you want to put this in space, you need to fit that stuff into a rocket.

But that’s a lot of stuff, especially the three bulkiest elements: solar panels, batteries, and radiators. SpaceX is building Starship, a rocket that can carry 150-200 tons to space at a cost that should reach ~$100/kg. That’s ~15x cheaper than what they can do today (and 45x cheaper than the competition), but it’s still quite expensive. So you want to strip as much of that weight as you can. How do you do that?

1. 5x Solar Power

Solar panels produce about 25% of the electricity they could theoretically generate because of the day-night cycle, the seasons, and atmospheric conditions like clouds or storms. But in space, the Sun is always shining. If you have the right orbit, you can keep your solar panels lit all the time, and that provides two benefits.

First, you get ~4x more direct sunlight, because the Sun will be perpendicular to the panels all the time, and there will be no night.

Second, when solar rays cross the atmosphere, they lose about ~30% of their energy.2 Eliminate the atmosphere, and you eliminate this loss.

Add these factors together, and you get ~5x (and up to 9x) more energy from your solar panels than you would on Earth—or, in other words, you need 5x fewer solar panels (and their mass) in space than on Earth.3

2. No Batteries

If your solar panels are perfectly illuminated, you don’t need to buy and transport the very heavy batteries, which represent over half4 of the total weight. Massive win.

But how do you get your solar panels to always face the Sun?

3. The Right Orbit

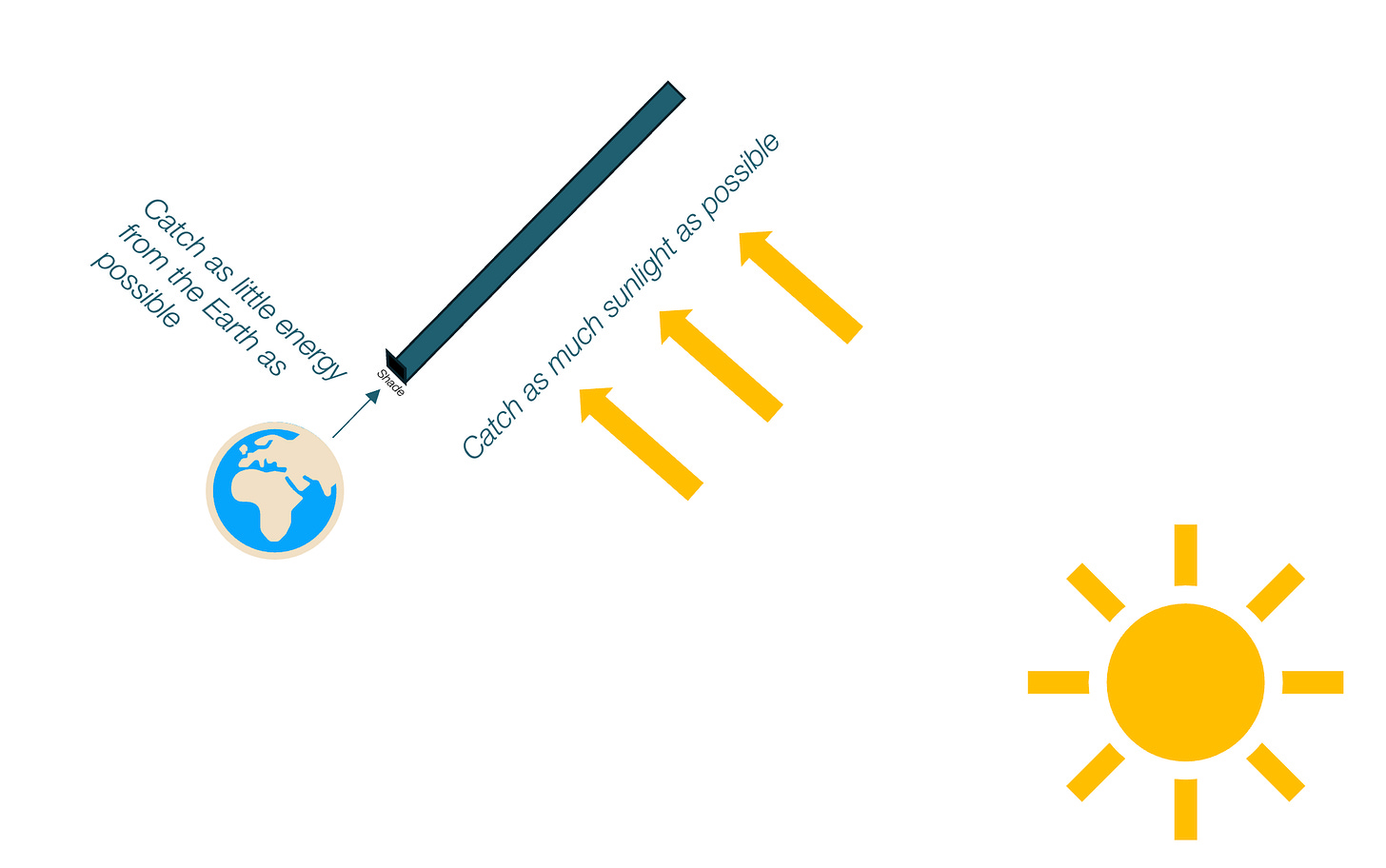

One way to achieve that is by orbiting the Earth around the poles, in what’s called a sun-synchronous orbit:

The problem with this is that it’s quite expensive to get satellites into these orbits. Normally, rockets are launched from as close to the equator as possible, in order to use the rotation of the Earth to move faster.

But if you send them into a polar orbit, you can’t use that inertia, so it’s much less fuel-efficient. It’s easier if your satellite follows an orbit that isn’t too distant from the equator’s plane.

The problem here is that the satellite ends up in the shadow of the Earth… Another solution is to send the satellite far enough from Earth,5 and not quite on the same plane as the equator, so that it won’t pass through the Earth’s shadow.

The exact orbit will need to optimize for:

100% sunlight

Closest proximity to Earth (to reduce fuel costs of the rocket to reach a distant orbit)

Efficiency for rockets from Starbase to reach

But if the satellites are far from Earth, isn’t this going to create some latency? Won’t signal take too long to come back to Earth? Yes, but it doesn’t matter:

Even if the satellites were far away, say at 5,000 km, the time for the signal to go back and forth from Earth would be 30 ms.

For most AI uses, a few milliseconds (or even seconds) of delay doesn’t matter that much. Think about how long some AI tasks take today, from seconds to minutes, and even hours!6

OK we got rid of more than half of the weight from batteries and 5xed the efficiency of our solar panels. What else can we eliminate?

4. Lighter Solar Panels

Once you’ve disposed of the batteries, the solar array is the biggest source of weight of Starlink satellites today,7 about a third of the total.

But in space, solar panels are much lighter than on Earth. A solar panel on Earth weighs8 about 10 kg/m2 or more9, while in space it can weigh as little as 1 kg/m2 or less.

That’s because, in space, there’s no gravity, atmosphere, rain, hail, dust… The panels only need to be lightly structured; they don’t need glass to protect them, aluminum frames, stiff backsheets, sturdy mounting, rails, clamps, grounding…

They do need some coating to protect against the intense solar radiation and flares, but if the satellites are close enough to Earth, they’re protected by its magnetic field, so with minimal coating, they can withstand failure rates of less than 1% per year.

Musk’s SpaceX (and Tesla!) design and participate in the supply chain of solar panels, so I assume they’ll adapt them as much as possible to their needs.

This is already quite optimized, though, so I assume there’s not too much more to do here.

5. GPUs

Now we need to optimize the weight of GPUs, but these are actually not very heavy relative to their cost. To get a sense of this, an NVIDIA GPU today costs ~$25k and weighs from 1.2 – 2 kg, while a fully-loaded system (if you add all the other costs, like memory, cooling, etc) costs as much as $56k and weighs 16 kg.

Sending 16 kg to space today is expensive ($24k), but it won’t be with Starship ($3.2k when it costs $200/kg, half that when it costs $100/kg). And that assumes all the weight of what we use on Earth would be carried to space, which is unlikely. These systems will be streamlined for weight, so that the cost of shipping the GPUs to orbit will be a tiny fraction of the cost of the GPUs. We’ll see in a moment why.

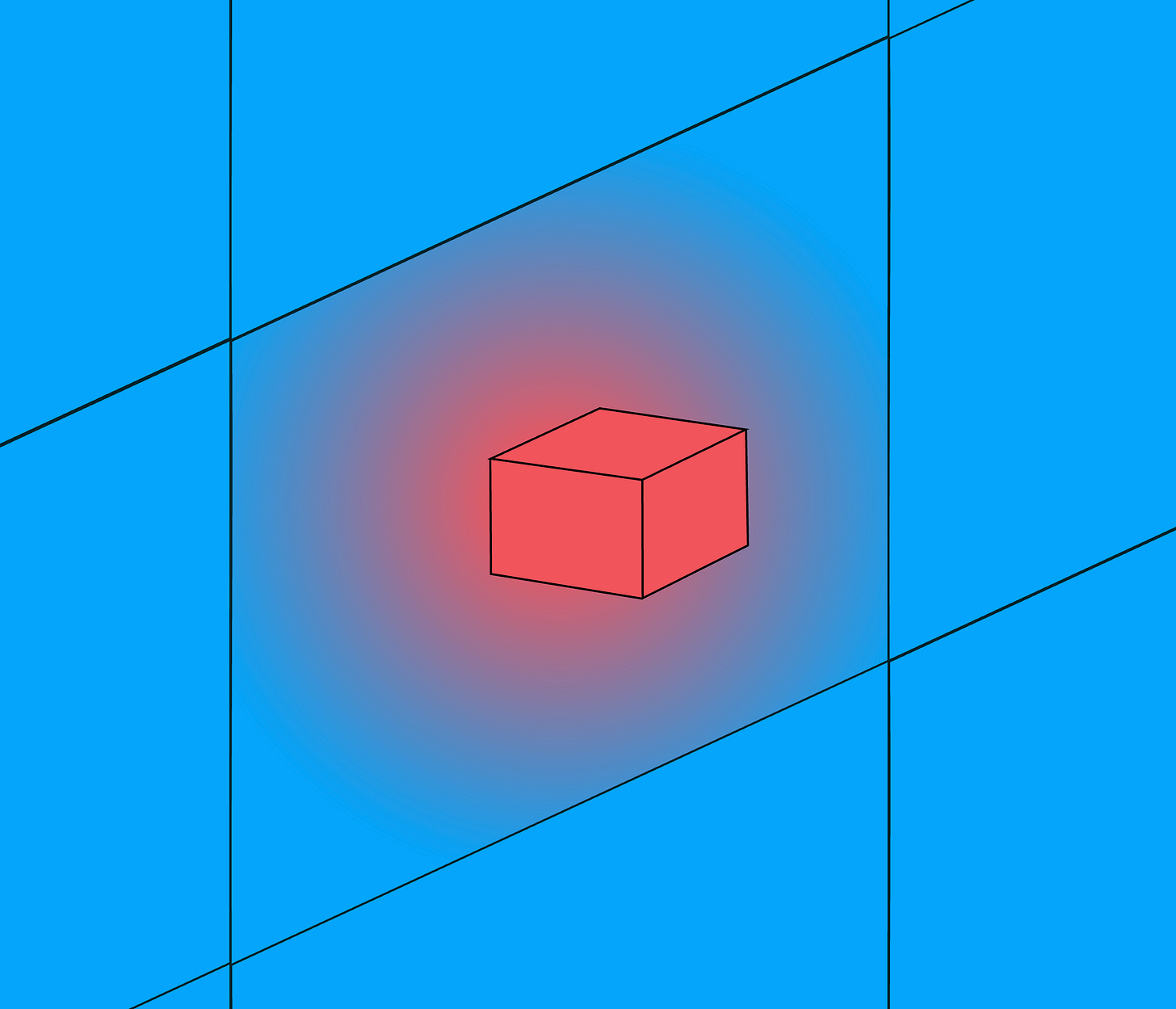

6. GPU Shielding

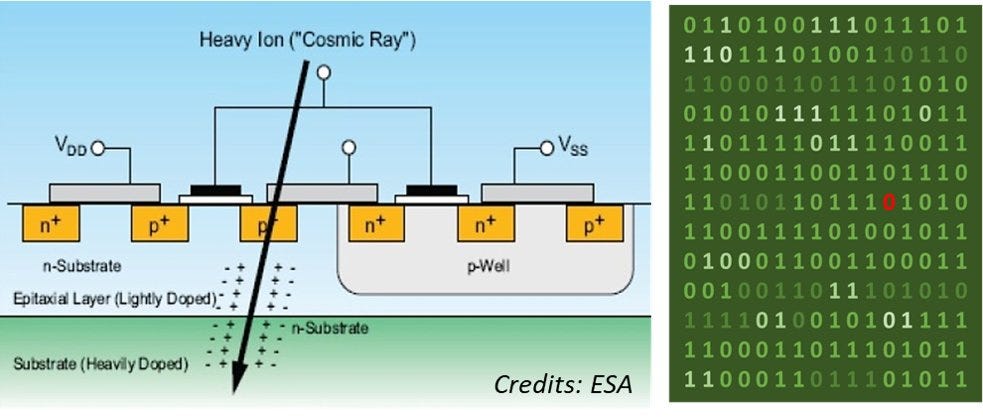

But besides their weight, GPUs face another problem in space: radiation. On Earth, we’re protected from solar electromagnetic rays by the atmosphere and our magnetic field, but these protections are much weaker in space—when they exist. This is a serious problem for computers in space today, because these rays cause mayhem in computers. As a result, they need shielding, which is expensive and heavy.

One of the issues is that electromagnetic rays flip bits and cause havoc in existing systems. For example, imagine that a computer has the following number: 1000001000001, which in decimal is 4161. If that first bit receives a solar ray and flips to 0, that number is now 0000001000001, which in decimal is 65. Imagine that you’re calculating 4161*10 and instead of getting 41,610, you get 650. Every downstream calculation will be monumentally off. Catastrophe! As a result, computers in space today require electromagnetic shields that add to their weight.

But this is not how AI works. AIs are not deterministic, they’re probabilistic. AIs have massive files with billions of parameters that each add a tiny amount to the final value. Querying a GPU is kind of like taking a poll to millions of people. Another way to think about it: In your brain, connections between neurons are constantly dying and forming. Any single one of them is not important at all. They can be severed, and everything will continue as normal.

The result is that GPUs don’t need as much electromagnetic shields as traditional computers, so this added weight can be avoided.

The rest of the software can also be adapted to this situation, tolerating random errors instead of assuming perfect calculations all the time.

Some systems, like the memory, will still need shielding, but if you’re limiting the shielding to only a few small parts of the satellite, the cost in weight will be tiny.

With this type of treatment, Google believes their chips can last 5 years in space—about the lifetime of a datacenter:10

We tested Trillium, Google’s TPU, in a proton beam to test for impact from total ionizing dose (TID) and single event effects (SEEs).

The results were promising. While the High Bandwidth Memory (HBM) subsystems were the most sensitive component, they only began showing irregularities after a cumulative dose of 2,000 rad(Si) — nearly three times the expected (shielded) five year mission dose of 750 rad(Si). No hard failures were attributable to TID up to the maximum tested dose of 15 krad(Si) on a single chip, indicating that Trillium TPUs are surprisingly radiation-hard for space applications.—Google

7. GPU Maintenance and Replacement

GPUs have a high failure rate, but you can’t swap them in space. So what are you supposed to do?

One of the measures will be to make them more tolerant to heat (we’ll talk about this next). This should reduce failure rates, especially in space.

But aside from that, most failures happen at the beginning of a GPU’s life, so if you test the GPUs on land first, you should be able to reduce the failure rate dramatically, so that your average GPUs lasts ~5 years.

8. Radiators

And now we get to radiators.

Before I started this article, this was my main concern. Radiators on Earth are very heavy, because you have the radiator, the fans, the cooling liquids… And in space, it’s even worse, because you can’t use the environment to cool off your machines! So I expected these systems to be huge, cumbersome, and prohibitively heavy.

But here’s the insight that blew my mind: Just using the front and back of the solar panels as radiators is enough to cool off the entire system! How is that possible? Here is the breakdown.

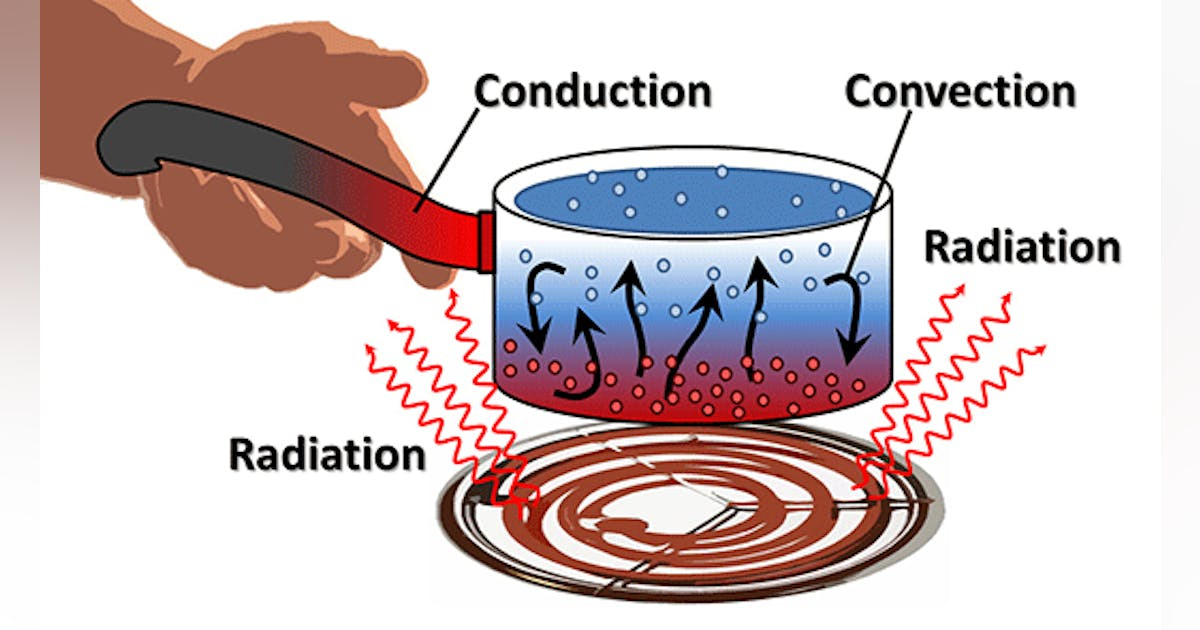

There are three ways of cooling something:

Conduction: Heat is transferred through a material, from a hot point to a cooler one. But in space your satellites are not connected to anything, so they can’t dissipate any heat out this way.

Convection: That’s like wind or water in contact with your surface, extracting heat from it. Same issue as before, there’s no wind or water in space.

Radiation: Like the heat from a lightbulb, a toaster, or the Sun: When something is hot, it radiates heat out. This is the only method you can use in space.

But it turns out that radiation is extremely powerful, because it transfers heat to the 4th power of temperature: T4!

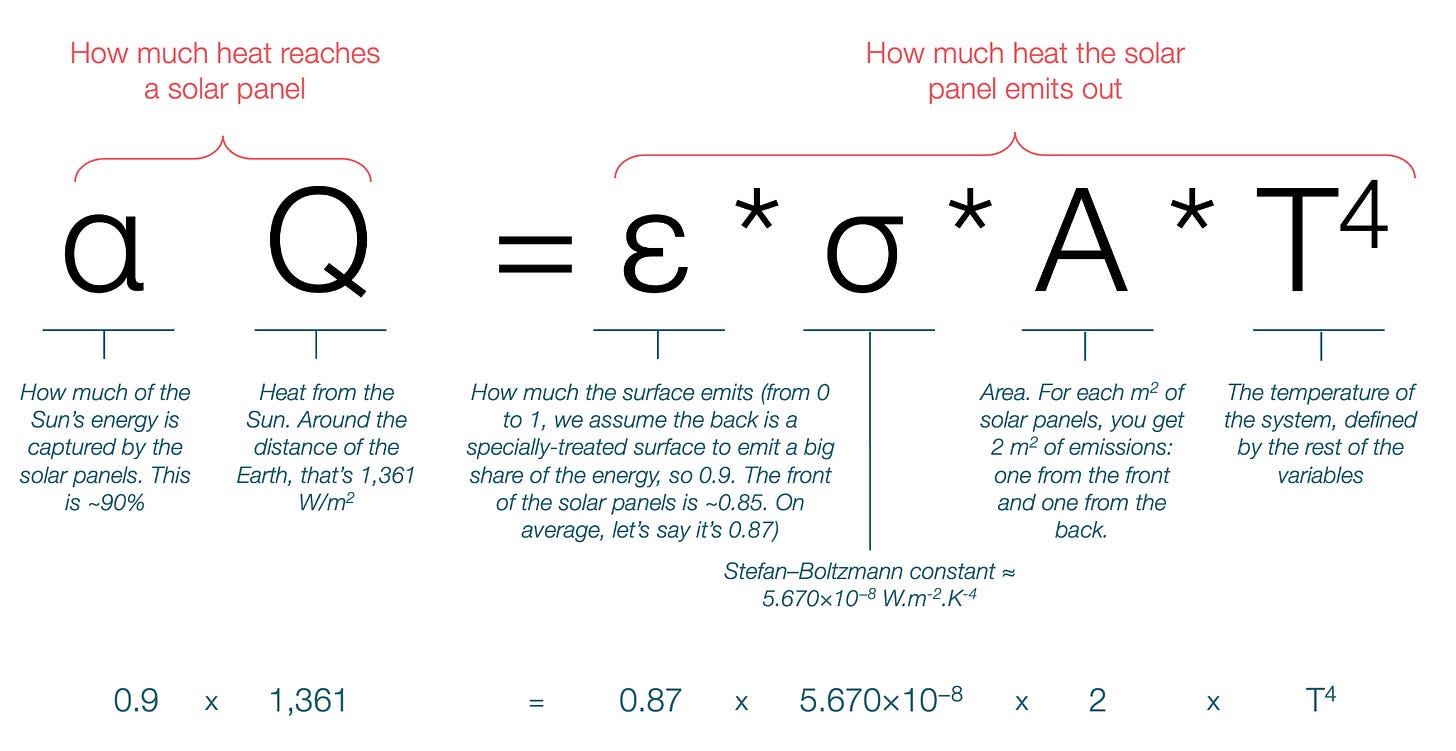

The actual formula is ε*σ*A*T4, but it’s pretty simple. The first variable (ε) is how good your surface is at emitting heat. A good radiator will be close to 1. The second (σ) is just a constant. The third (A) is the area, but we’re going to look at this per square meter of solar panels, so it’s 1, too. The last item, Temperature, is the one that matters. For a given area that is efficient at emitting heat, it’s the only component that has a massive impact.

To give you a sense of how powerful this is, if you move from emitting radiation from 20ºC to 100ºC (68ºF to 212ºF), the heat emitted through radiation is going to increase by 2.6x.11

Why is it raised to the power of four? It was never explained to me in engineering school, but according to ChatGPT, it’s because the energy of the photons being emitted grows in proportion to the temperature (one T), and these photons are emitted throughout all three dimensions (three more Ts), for a total of four Ts.

Anyway, the point is that you can emit a lot of energy through radiation, and your solar panels are enough to cool the entire thing.

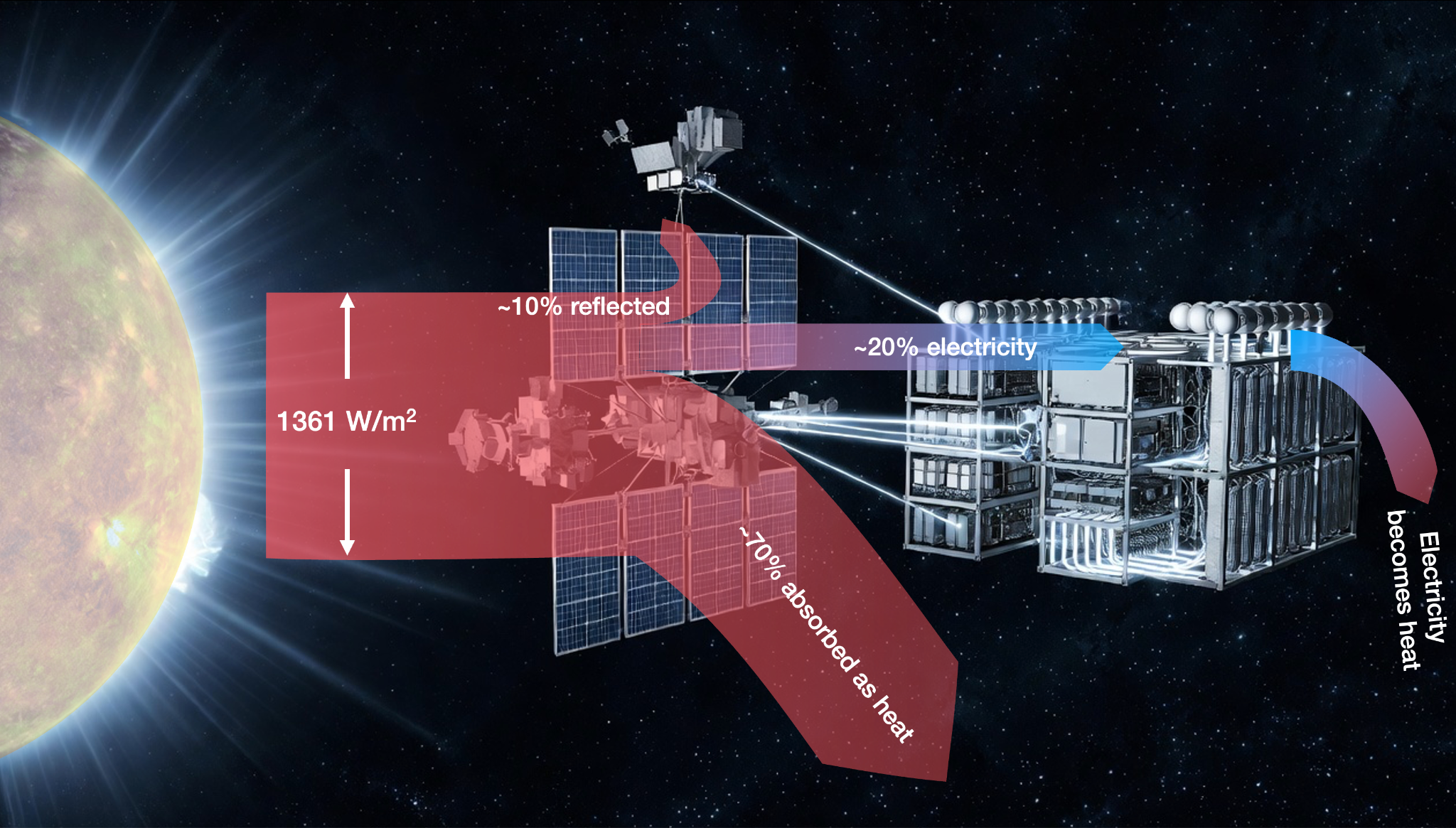

The way the datacenters work is that the solar panels get the energy from the Sun—about 1,361 W/m2. They reflect a bit less than 10% of that, so let’s say they absorb 1,225 W/m2. They convert about 20% into electricity (so ~272 W/m2) and the rest becomes heat. The electricity is sent to the GPUs, and in the process, that electricity becomes heat, too. The heat of the solar panels and GPUs must then be dissipated through radiators.

For the system to maintain a certain temperature, it must lose as much energy as it takes in, so the 1,225 Watts it absorbs per square meter must be radiated out. This happens through both the front and the back surface of the solar panels. So you have:12

That gives you T=60ºC (334 K, 140ºF)! Now this is a bit idealized. In reality, the satellites will also receive heat from the Earth, so they’ll be a bit hotter. But there are ways to minimize that heat:

More importantly, GPUs are normally cooled with heavy radiators and liquids, which xAI and SpaceX want to avoid, so they won’t perfectly dissipate their heat and will run at a higher temperature than on Earth (or the solar panels in space). Musk believes they should run at 97ºC (207ºF). For comparison, GPUs normally run at ~80°C, with a max around 88 – 93°C, but they can tolerate ~90-105°C in datacenters, so this is not too far off. Industrial- and military-grade silicon commonly stands up to ~125°C. The GPUs just need to be optimized to run at a slightly higher temperature than they’re used to on Earth.

This is another reason why it’s so important that SpaceX and xAI have merged: xAI is designing its own chips and will now start adapting them to this type of requirements.

The heat generated by the GPUs must be transferred out. It’s unclear whether this will be through radiators on the GPUs themselves, or by conducting heat back to the solar panels to be dissipated there. In any case, there will be some mass associated to that, but it doesn’t look like it will be too much

9. Bus

The bus is the thing that usually carries all the stuff a satellite actually wants in space.

In Starlink, they include the thrusters and communication devices like antennas and thrusters to maneuver. The datacenters would still need the thrusters, but the need for communication devices would be tiny. I’m not sure whether the GPUs would be lodged there or more distributed behind the solar panels for heat dissipation.

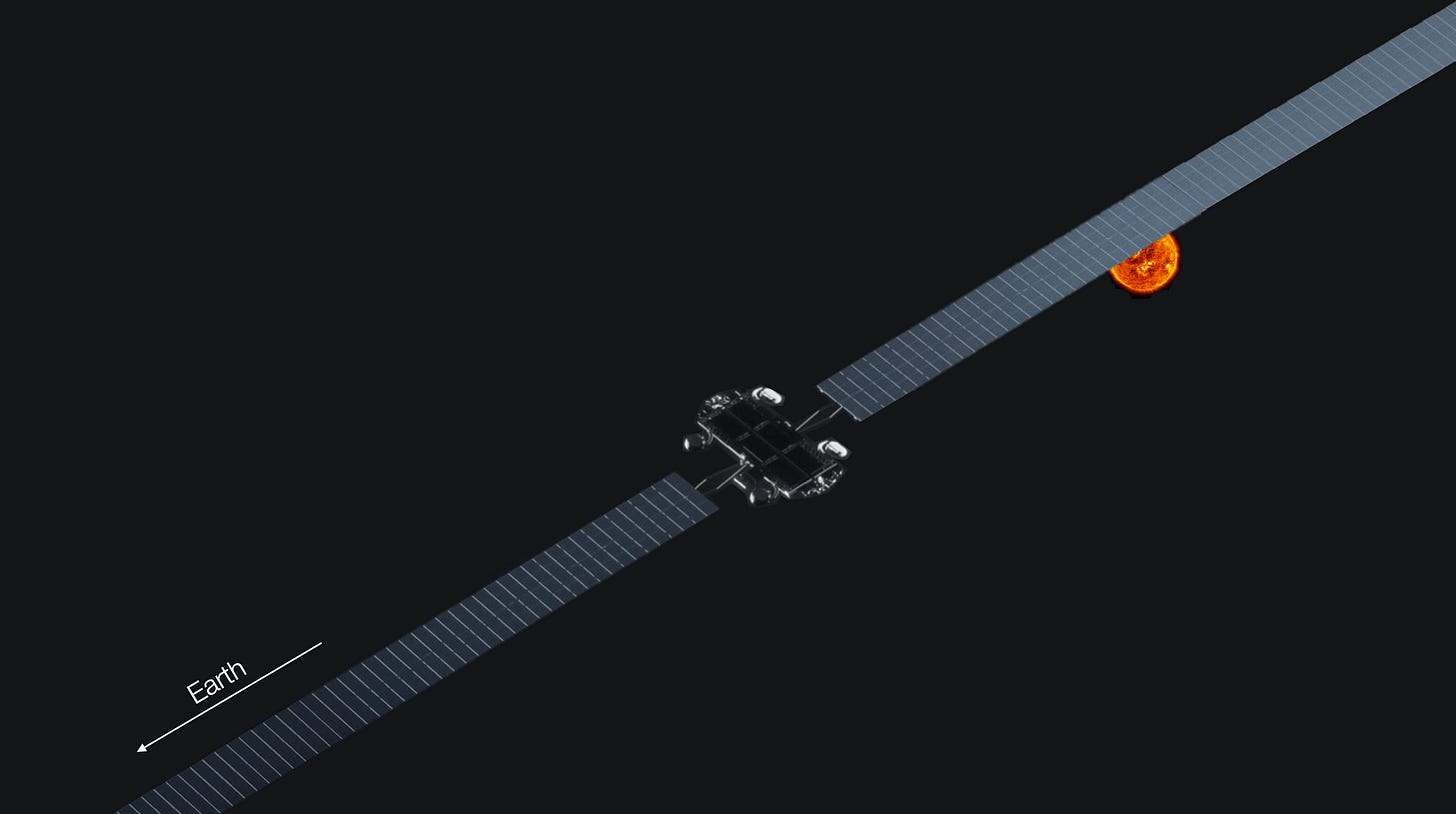

OK, so now we have a broad sense of what these space datacenters should look like:

Lightweight solar panels to gather electricity

Use their front and back for cooling

Add the GPUs and other computing systems, including the bus. Some of these parts will be shielded from solar radiation, others won’t

The system should run below 100ºC

That’s it! No radiators, no more heavy equipment!

Is this going to be cheaper than building datacenters on Earth? To answer that, let’s see what a real one would look like, and compare it to one on Earth.