Climate Caused the US Civil War

The story people know about the US Civil War is that the South had slavery and the North was free. As each side expanded westward, they feared that the other side would prevail and force their solution on the other, and eventually they went to war over it.

That, right there, should give you pause: North and South? Westward expansion? Did geography have something to do with the Civil War? More than that: I think geography caused the Civil War. How?

Because of climate, the North farmed crops like wheat and barley that required very little work, and that work was easy to automate. This tended to make farmers independent, incentivize industrialization for the machinery, and push settlers west very fast, as they weren’t as limited by labor needs.

Conversely, the crops grown in the south—mainly cotton, tobacco, sugarcane, and rice—all require substantially more work, so getting lots of workers at the lowest possible cost made or broke fortunes. This is why slavery emerged here, why it was fundamental to the South’s economy, and why Southerners went to war to continue it.

Why does all this matter? It’s not just a crucial fact of US history. This has dramatic consequences today, from the roots of racial inequality, to where the Democratic party wins elections, and the relative poverty of the US South.

So let’s dive in: How exactly did climate cause the Civil War, and what are the consequences of that today?

The Slavery Race to the West

For decades, the rush westward had been fueled by one clause of the US Constitution:

The Senate of the United States shall be composed of two Senators from each State.

If one side has 50% or more of senators,1 it can block any legislation it dislikes,2 including the most controversial one at the time: slavery.

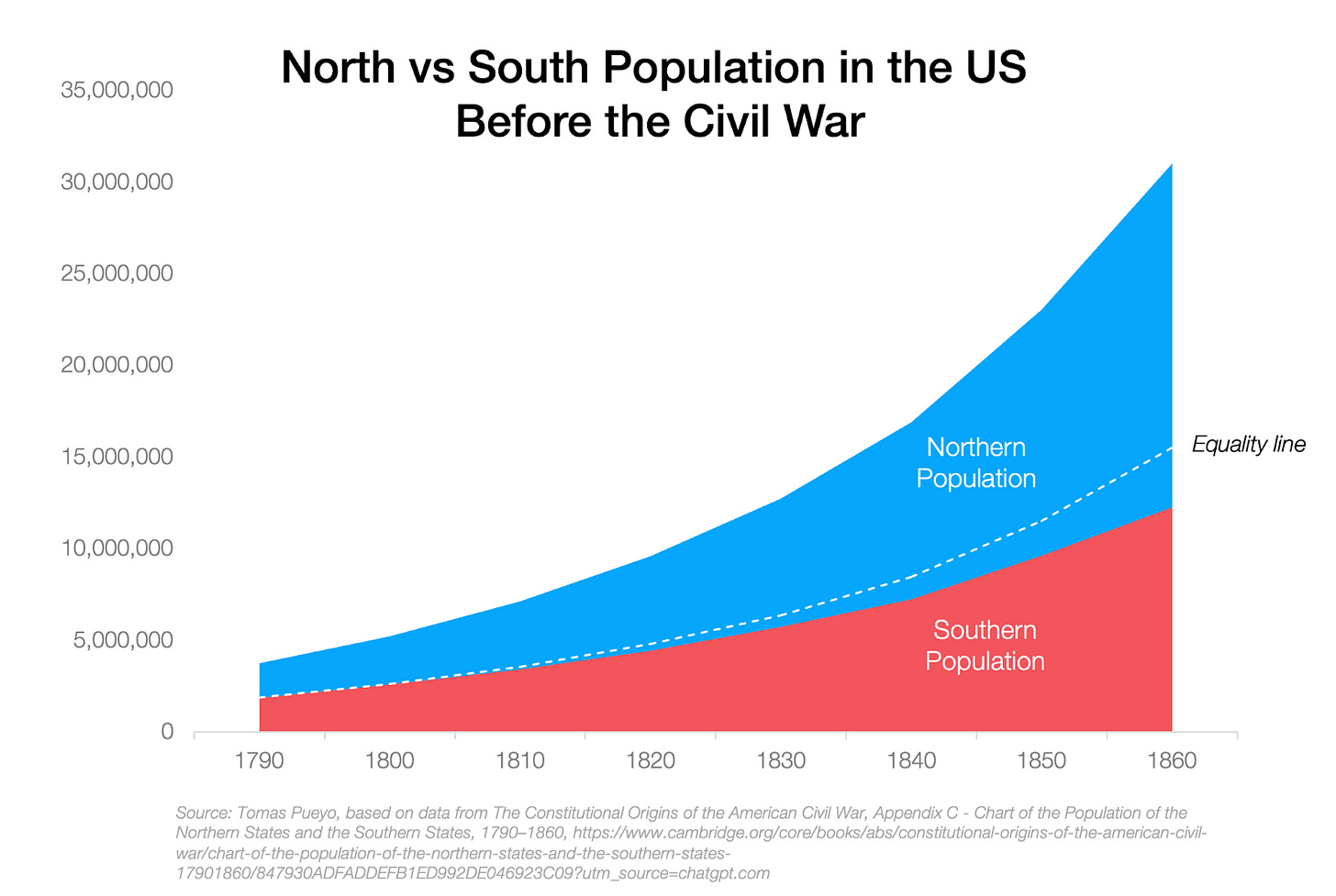

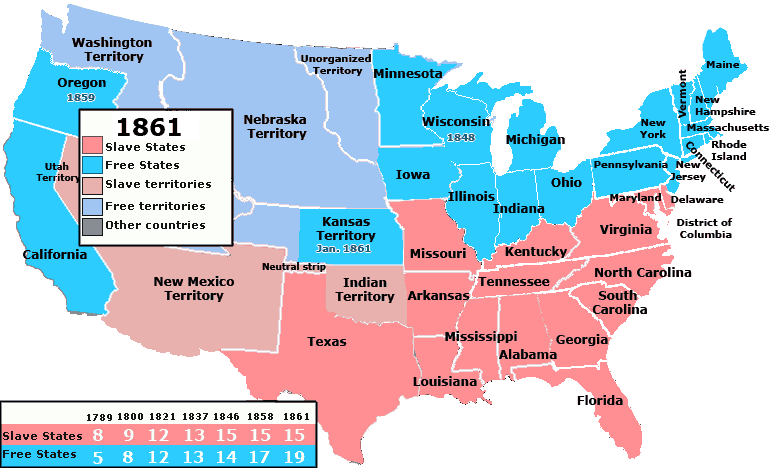

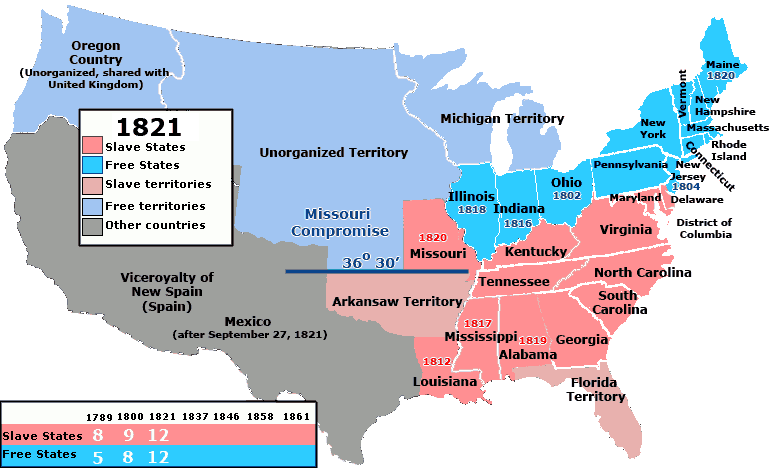

This is the evolution of free vs slave states between 1789 and the eve of the Civil War in 1861:

When the US became a country, it had more slave states than free states. But over the following decades, the northern population and its expansion accelerated. By 1820, there were the same number of slave vs free states. A bigger population in the North meant it controlled the House, but as long as the number of free and slave states was the same, the public mandate would not clearly support abolition, and Northerners wouldn’t have a majority to impose it, as Southerners could block any anti-slavery legislation in the Senate.

In 1820, Missouri wanted to become a (slave) state, but that would have upended the balance, so the Missouri Compromise was reached: The US would also accept Maine as a state, keeping the balance, and from thereon free vs slave statehood would be determined based on the 36º30’ parallel, north of which states would be free.

This bought some time, but cemented the idea that each side had to rush westwards as fast as possible to create new states for their camp, lest it lose the senate balance.3 And the South saw the writing on the wall:

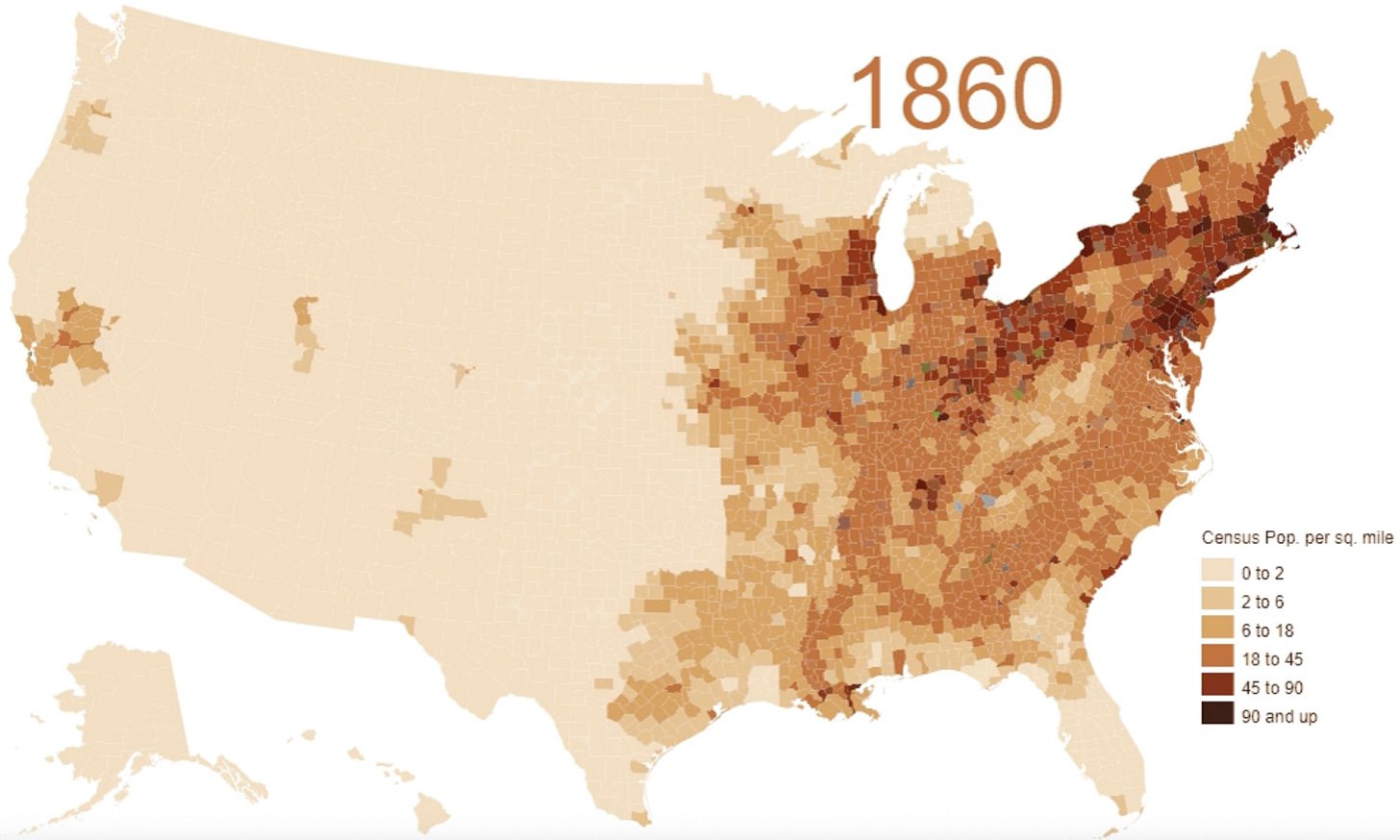

The Northern population grew faster than the Southern one. The result was this population density map on the eve of the Civil War:

The Southerners dreaded the arrival of each new census: They feared this population imbalance meant the North was going to make new states faster, threatening slavery. They were right.

By 1860, the North had three more states than the South. Lincoln campaigned for the 1860 election on an anti-slavery platform:

We deny the authority of Congress, of a territorial legislature, or of any individuals, to give legal existence to slavery in any Territory of the United States.—Platform Adopted by the National Republican Convention, held in Chicago, May 17, 1860. Library of Congress.

As soon as Lincoln won, and before he was even inaugurated, Southern states started seceding.4

All of this shows that the single most important cause of the Civil War was slavery, and it came to a head when the North’s population outgrew the South’s.

But hold on, why was the Northern population growing faster than the South’s?

Feeding the Northern Growth

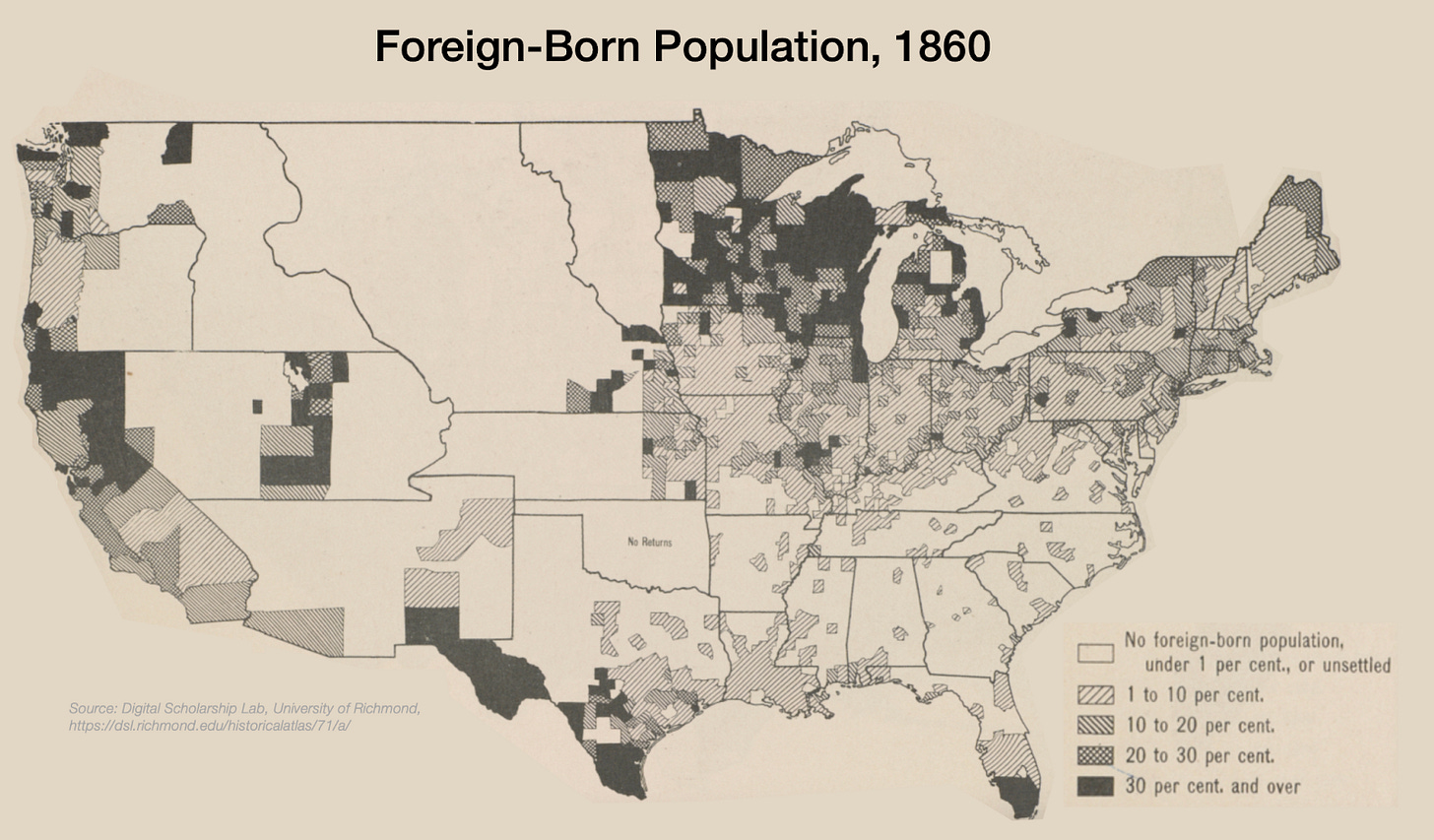

Most immigrants went to the North.

Nearly 90% of foreign immigrants settled in free states.

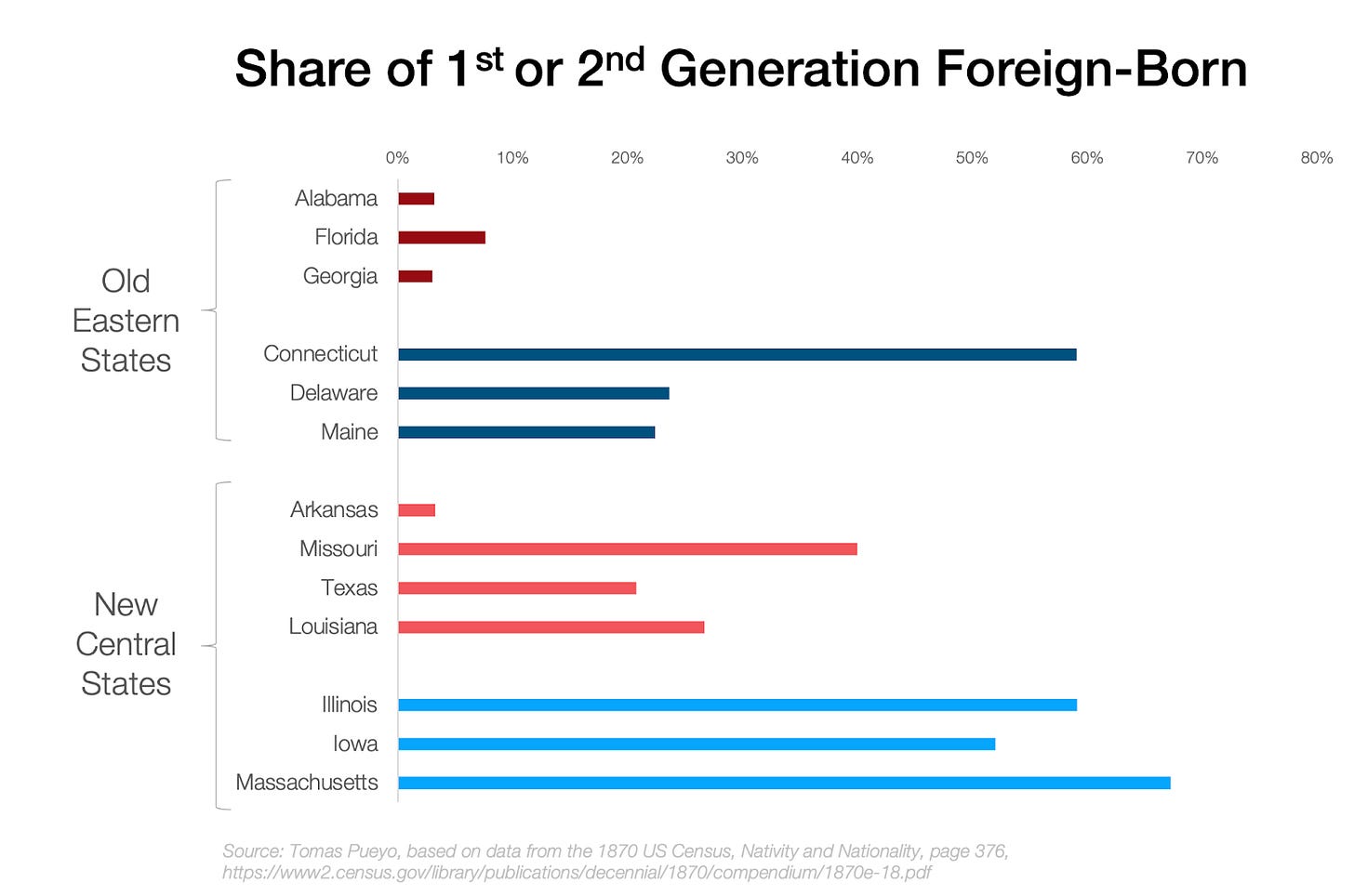

Then they had children, and those had children, and the population of the north grew faster. I spot-checked the share of population that was either foreign or had a foreign parent, and this is what it looked like:

Northern states tended to have a much higher share of foreigners than Southern states because they received much more immigration.

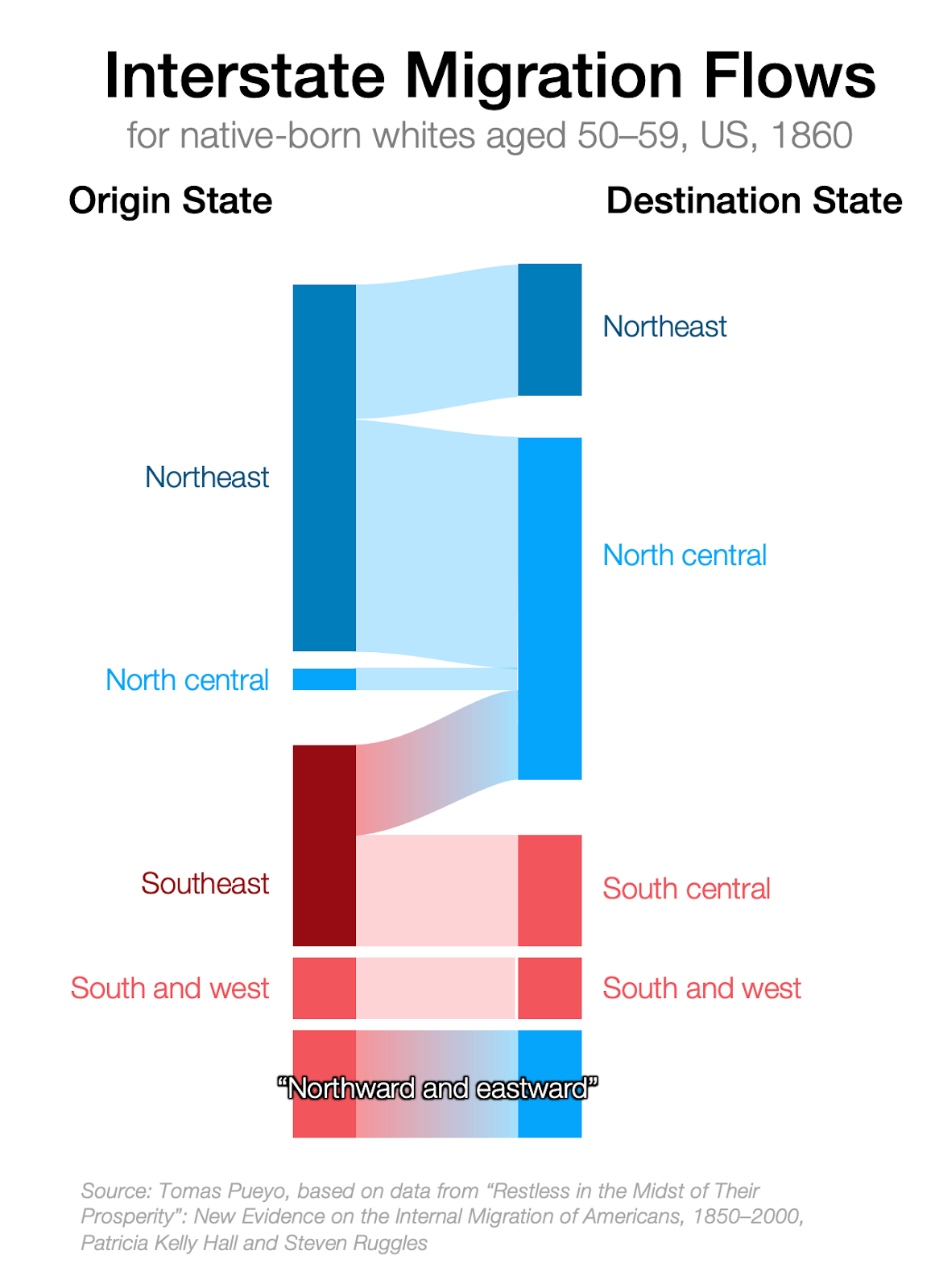

It wasn’t just foreigners coming to the US; there was also massive internal migration of Americans moving westward: Around 1850, nearly 50% of Americans had moved from their state of birth!5 But they tended to choose Northern states over Southern ones.6

So now we know the Civil War was caused by the disagreement over slavery, that it erupted when the North outgrew the South, and that this happened because foreigners and Americans moved to the North en masse.

But why did immigrants go to the North?

The Magnetic North

About 90% of immigrants7 went to the North, a majority to work in farms:

The South had slaves, which depressed labor costs, and wages in the South were lower.

The North made it easier for immigrants to own land and reap what they sowed.

The industry in the North was more diversified, so workers had options beyond farming.

Mortality was higher in the South.

And why is all this the case?

This is a map of crops in 1860, just before the US Civil War (1861-65):

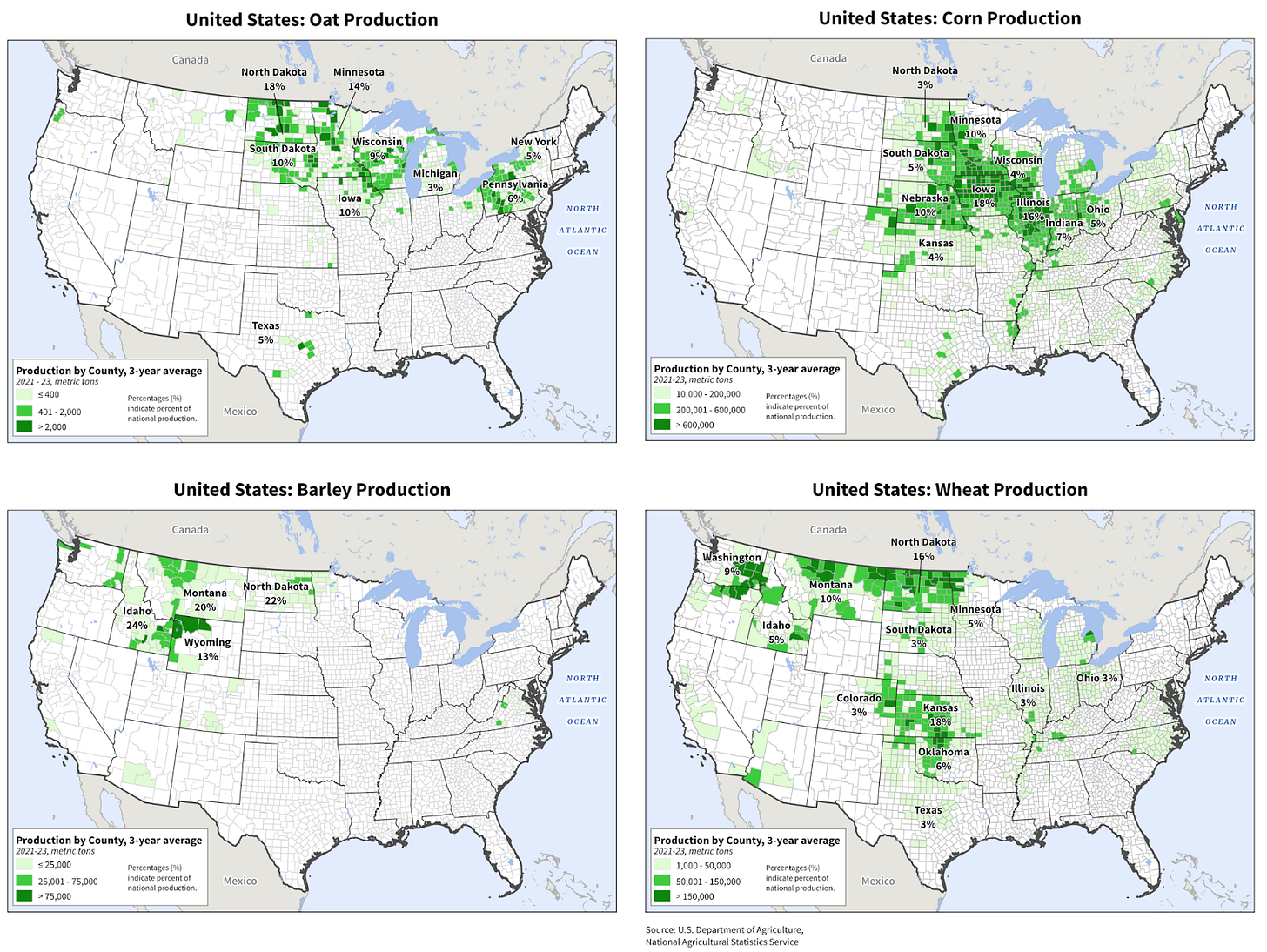

The drier and cooler North grew mostly wheat, barley, and oats.8

The warmer and more humid South grew mostly cotton, tobacco, sugar, and rice.

This is actually not that different today. These are the traditional northern crops:

And for the South:

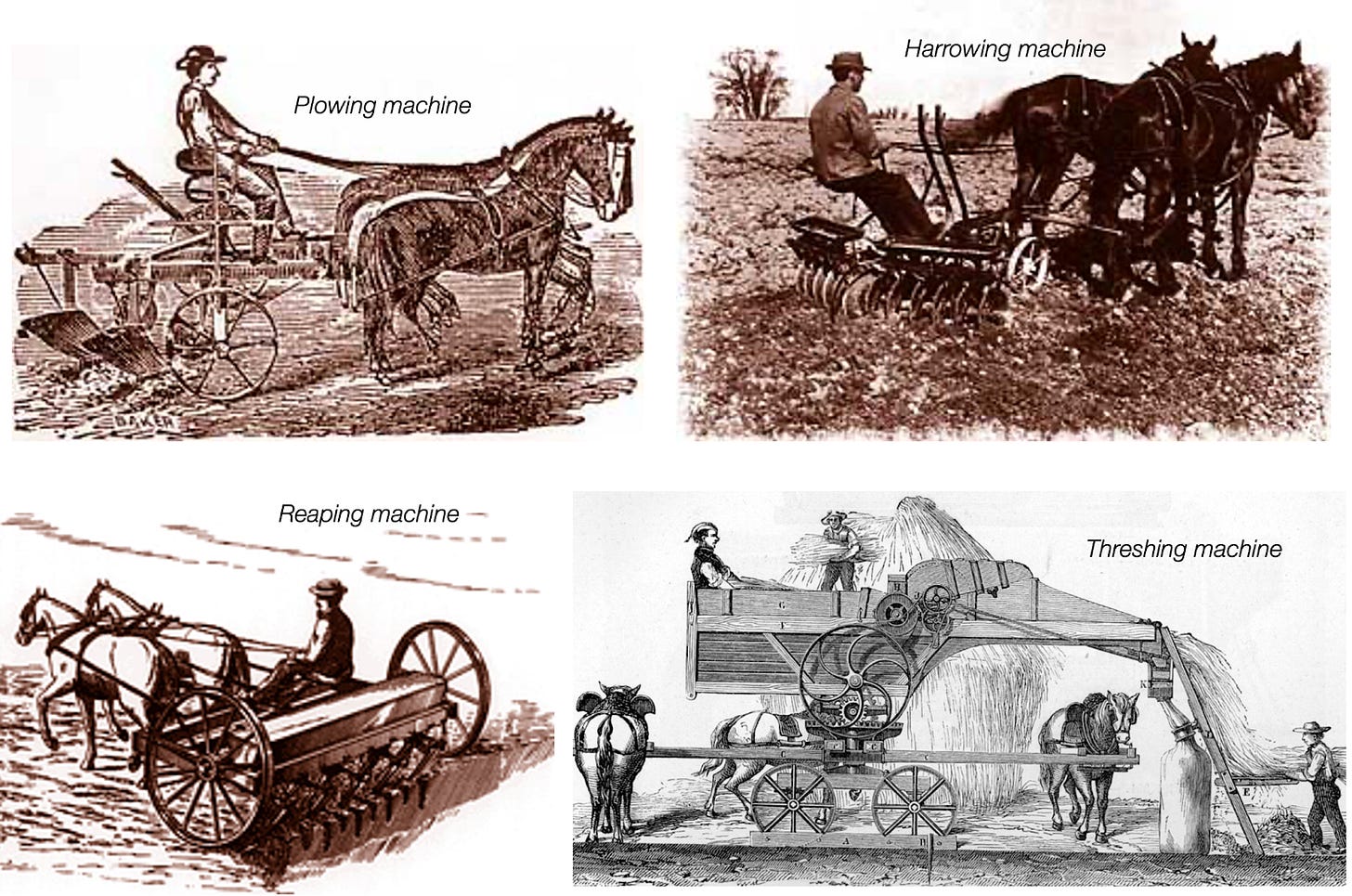

This sounds like a small difference, but it’s so momentous that we can consider it the single biggest driver of the Civil War. Why? Because wheat, barley, and corn grow in northern climates and happen to require much less work than cotton, tobacco, sugar, and rice, which grow in southern climates. This led to families taking care of small independent farms in the North and big landowners setting up plantations worked by slaves in the South.

The Crop Divergence

The Ease of Northern Crops

Raising crops generally entails three phases:

Preparing the soil and seeding

Harvesting

Post-processing.

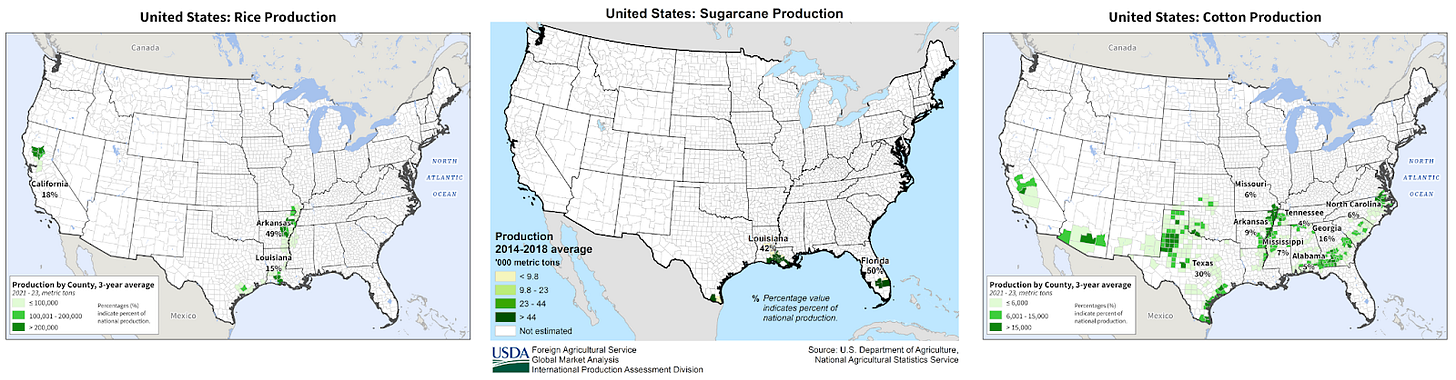

For northern crops, these processes were easy,9 and tools (and later, machines) made it even easier.

For example, preparing the soil for wheat or oats required plowing and harrowing fields, and sowing, which took about 13 hours per acre (13 h/a).

Then came reaping season, which could be done in one pass of cutting the wheat, aligning it, bundling it, and putting the bundles upright to dry. This took about 14 h/a.

Finally, you had to thresh: Extract the grain from the stalks, and then from the husk. This took about 8 h/a,10 for a total of about 33 h/a.

Luckily, each one of these steps was easy to mechanize:

Mechanization was happening through the 19th century, and shrunk the work to produce wheat from 33 h/a in 1839 to 11 h/a in 1910.11 As an example, by 1860, a threshing machine could thresh 12 times as much grain per hour as could six men: That’s a 70x improvement in productivity per hour! On average, in 1840, wheat took 33 h/a, oats 31 h/a, and corn 61 h/a.12

Harrowing Southern Crops

That was not the case in the South. Consider cotton, which accounted for over 60% of US exports in 1860.

Cotton took about 130 h/a of work!13

An acre of cotton required 4x the work as an acre of wheat.

What?!

How is this possible?

Cotton requires about 70 h/a of field preparation, and about 60 h/a of harvesting,14 so each step took much more work than the entire wheat cycle!

To prepare the land, the woody cotton stalks must first be cut, or they jam the plow. Then, since cotton likes humidity but doesn’t like the ground to be waterlogged, it must be plowed once, and then ridges need to be made to plant the cotton above the rest of the ground. Then, the ridges must be somewhat leveled so that the cotton seeds don’t fall too deep. Then, planting must be done accurately, so that the distance between plants is ideal for pickers to optimally run between them. The seed is small so it must be planted carefully near the surface. Later, as there are plenty of seeds, you get overseeding, so too many plants grow. Some need to be cut early. And finally, since it’s warm and humid, a lot of weeds grow, so fields need to be constantly weeded.

That’s just the soil and sowing work! The picking also took much longer than wheat because:

Wheat (and oats, barley, and corn) is a strong grain, but cotton is a delicate boll that must be hand-picked.

Cotton bolls don’t open at the same time, and they need to be harvested as they open, so cotton requires multiple harvest passes! While wheat, corn, oats, and barley can all be harvested together.

Also, a lot of this work could not be easily automated, because the bolls were delicate, the plants all differed in opening times, the soil was wet and uneven… Mechanization of cotton has taken much longer than wheat.15

This is the case for cotton, but as we saw, rice requires 2x more work than wheat. And that’s the easy one. Tobacco and sugarcane required an overwhelming amount of work: around 250 h/a for sugarcane16 and 300-900 h/a for tobacco,17 or 10x to 30x more than wheat! Why?

Tobacco exhausted soil quickly, after just a handful of seasons, so new farmland had to be bought and the workers had to move all the time. Then, tobacco needs to be grown in a nursery before being transplanted. Huh? Tobacco seeds are like dust, with thousands of seeds per gram. They need a very fine, weed-free, moist surface to germinate. If you broadcast them onto a plowed field, most would be buried too deep, dry out, or be swamped by weeds.

Tobacco must then be grown with precise spacing for airflow, disease control, leaf development, and picking ease.

The leaves must remain intact, so they have to be picked by hand. Then, they have to be carried to barns to cure.

Sugar cane was another highly complex crop. For example, the soil had to be plowed deep, and needed straight furrows; what you plant is last year’s cane stalks, which are bulky and heavy and must be placed one by one. Sugarcane has to be cut and then immediately crushed and boiled in sugar mills on-site, which meant you couldn’t harvest everything at once, and needed lots of coordination.

This is the result:

The Economic Divergence

In the North, a single family in a homestead was enough to handle a big farm. At most, families could live in villages to help each other, but they remained fiercely independent. They preferred owning their farm so they could improve it and invest in machinery to cultivate more land and improve yields with less work. This led to freedom, entrepreneurship, and the ability to grow rich through wit and grind. Of course people flooded to the north!

This economic path didn’t require slaves: Slavery is actually expensive because you need a management layer to coerce the slaves, and even then, slaves work against their will. Entrepreneurship and freedom remove this inefficiency, so by 1830, Northern states had virtually abolished slavery.

Meanwhile, in the south, crops needed massive amounts of work. This meant that the biggest share of costs was human labor. There was a huge incentive to lower that cost, and slavery was the answer: With paid labor, these cash crops would have been uncompetitive in the world market. A natural approach to this would have been to automate the work as much as possible, but this was impossible at the time given the requirements of these crops.18 So White landowners turned to the horrible solution that was actually available to them at the time—slavery.

In the 19th century, slaves were 2-5x cheaper than wage workers, and were probably more productive,19 so the Southern White farmers who could afford it bought land, slaves, and created plantations, as they had existed in the region and the wider Caribbean for centuries.

By the time of the Civil War, the productivity of these crops had improved enough, and the cost of slaves increased enough, that cultivating these crops with paid workers was possible. But by then, the system was locked in: The Southern farmers didn’t want to lose their massive investments in slaves and juicy profits! Their entire economy depended on these slaves, and they were willing to go to war to keep them.

Something Bad’s in the Air

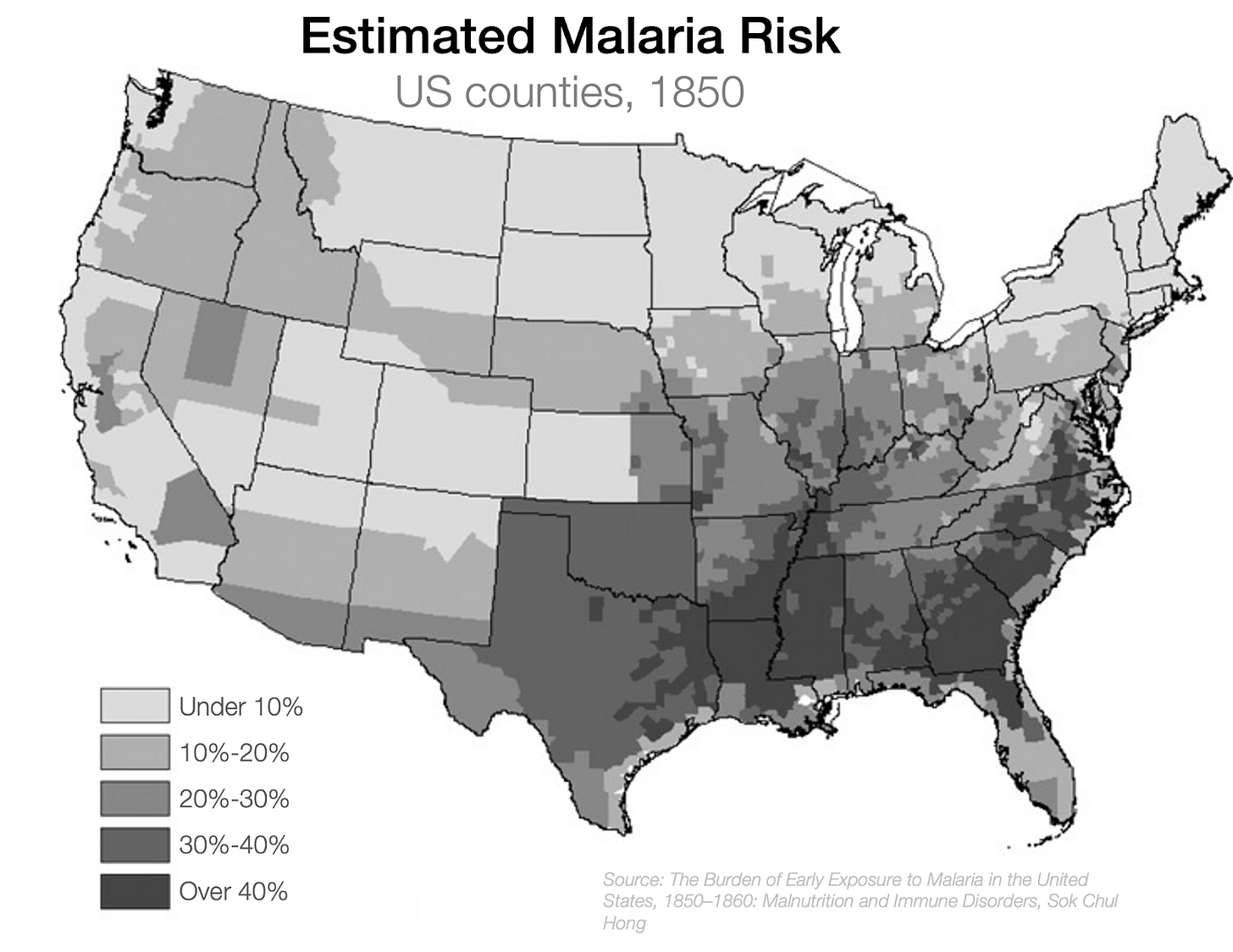

There was another reason why immigrants shunned the south: the bad air, or malaria.

Mortality was likely lowest in New England and rose as the latitude moved further south.—The Urban Mortality Transition in the United States, 1800-1940, Michael R. Haines

Malaria was pervasive in the South, because it’s hot and humid, and mosquitoes thrive there.

A child with malaria, if not killed outright, suffers stunted growth, lethargy, and decreased cognitive development. An adult with chronic malarial infection is often listless and weak.—How four once common diseases were eliminated from the American South, Margaret Humphreys

The impact can be seen by the fact that malaria eradication raised income in the “malaria-free” generation born in the next decade by 15%. Going back to the Mason-Dixon line that originally separated Free and Slave States:

Below it the Plasmodium parasite [that causes malaria] could live, and above it, the vector mosquitoes would survive, but the Plasmodium inside them would die.

Malaria was not the only disease in the region: Yellow fever and hookworm also festered there.20 White immigrants didn’t want to go there to die, especially since this was before the discovery of quinine, which allowed Europeans to move to tropical regions.

Meanwhile, Black Africans had more natural immunity to malaria specifically, and also some of these other diseases, or they had suffered some of these diseases in the past and had stronger immunity against them. So Black slaves were a better choice than Whites for working these crops in the South: They died less and had fewer down days.

Conclusion

Imagine you are a European descendant living in 1850, a hard and cruel world, but also a world full of discoveries and economic opportunities. Where would you rather go:

To the North, where you can get your own land and become rich by yourself through grinding and mechanizing your farm, or work in industries for higher wages than in your homeland?

Or to the South, where you could die of disease, and your main job option was to compete with slaves to grow crops that are hard to mechanize?

Early immigrants to the US knew this and went North. This tipped the balance of population towards the North, where slavery was not economically necessary, so it was abolished. Then, as the Northern population grew and their abolitionary stance strengthened, they pushed for imposing abolition of this abhorrent economic system on the South, who depended on it.

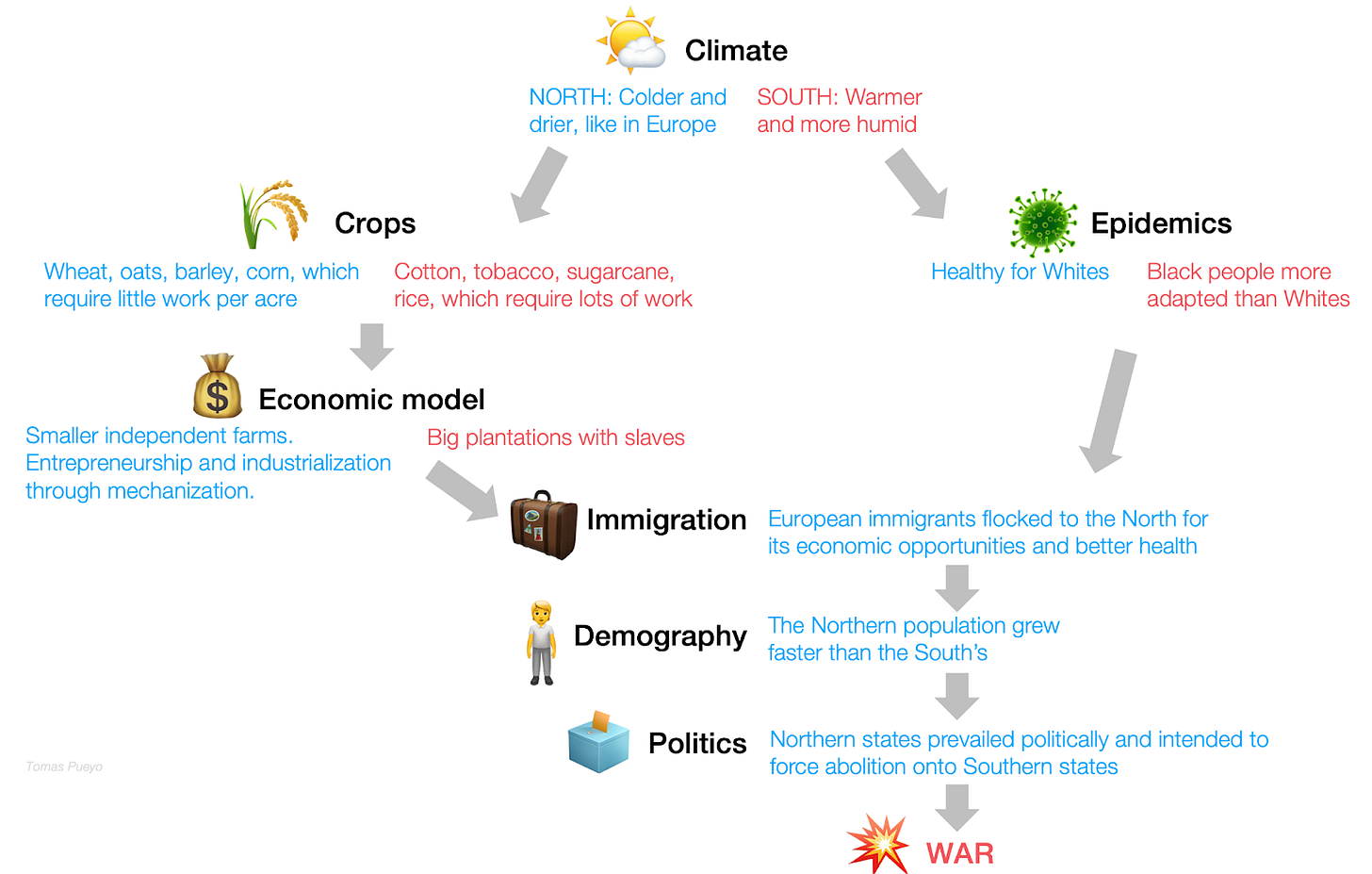

If you track the entire chain of causality, this is what it looks like:

And this is how climate caused the US North and South to enter into Civil War.

Why does all this matter? Why does GeoHistory matter, more broadly?

Because for centuries, humans have been fighting each other, blaming each other for their past behaviors and their grievances and what they are owed. Yes, slavery is absolutely abhorrent. What was done is terrible. But if instead, we see history as a mechanism, as the result of massive, hidden forces like climate and crops and economics, we can stop blaming each other for people’s terrible past deeds, and try instead to understand these mechanisms to steer humanity in the right direction, together. That’s what Uncharted Territories is about.

In fact, you can go farther: This is also why, before the Civil War, its outcome was already determined. And not only that, but the future development of the US North vs South for the following decades was also determined. For the 160 years since the US Civil War, the South has been catching up with the North due to the hindrance of its economic model, determined by climate. This is what we’re going to explore in the upcoming articles.

Since the US is bicameral, which means it has the House and the Senate, and both need to agree to approve a law. With filibustering, even fewer senators are necessary to block some types of legislation.

Bills need to be approved by the House and the Senate. The House represents population, and the Senate represents land (states). If one side has a majority in the House, but not in the Senate, its legislation can’t pass. In the Senate, a 50-50 split could be broken with the vice-president’s vote, and for some legislation, it’s a majority of 60+ that’s needed to pass the Senate.

Another push westwards in the South was the huge global cotton boom triggered by the cotton industrial revolution around Manchester, in England. But this pushed for settlement westward, not for incorporation into states.

The conflict between states on slavery had been heightening for decades: the Fugitive Slave Act of 1850, personal liberty laws, the Kansas–Nebraska Act that effectively repealed the Missouri Compromise, Bleeding Kansas (a kind of dress rehearsal of the Civil War), the caning of Abolitionist Senator Charles Sumner, the Dred Scott vs Sanford case that ruled that African Americans couldn’t be US citizens, the raids and execution of John Brown…

And 75% of working age males disappeared from their communities to move elsewhere!

This is why between the Missouri Compromise and 1860, only Florida, Arkansas, and Texas became slave states, whereas in the Midwest, Michigan, Wisconsin, Minnesota, and Iowa became states, on top of Oregon and California of course. While Texas became a state because of the war the US won against Mexico.

More Whites than Blacks, and more males than women.

Corn is more mixed. It tended (and tends) to be farmed more in the north, but could also grow south of the standard North-South line.

For wheat and oats, the first phase included plowing the field, harrowing (breaking up soil clods, leveling the field, and uprooting weeds), and sowing. The second phase included reaping, raking (aligning), binding, and shocking (putting the wheat bundles (shocks) upright to dry). The third phase included threshing (separating wheat grains from their husks and stalks) and shelling (removing the protective husks).

From this paper: Preparing the soil and sowing went from 13.6 h/a to 5.5 h/a; reaping and preparing the stalks from 13.9 h/a to 2.4 h/a. Every acre went from producing 11.3 bushels per acre (b/a) to 14 b/a, and the processing of every bushel went from 0.73 h/b to 0.2 h/b, for a total of this third step of 2.8 h/a.

From the same paper. Corn took much more time because, although farmers didn’t need to work on the ear as much (the bundle of yellow grains), preparing the land was much more time-consuming. It required field preparation, planting, cultivating, and hoeing, which took 61 h/a.

This is actually quite hard to find. The data comes from here, but different breakdowns of the tasks give different numbers. This makes sense, as there are differences in regions, in soil quality, in weather, in productivity, in varietals, in data quality… For this purpose, we don’t care exactly how many hours or work per acre were required, only why, and orders of magnitude of how much more work they involved compared to Northern crops.

After the invention of the cotton gin, working the cotton to extract the useful fiber became much easier, (so cheaper, as fewer hours were needed), so the processing went from extremely laborious to very fast and easy. This is, in fact, what allowed the cotton boom, as suddenly the cost of processing became low enough that a mass market could afford cotton clothes. This then triggered a big part of the English Industrial Revolution.

A lot of the automation in cotton farming actually happened in the 20th century. For example, forcing the blooming at the same time required breeding specific varieties of cotton and using defoliant, and it took hundreds of iterations for machines to be able to pick cotton. All these innovations converged around the 1940s, 80 years after the Civil War.

I count 32 person-days per acre, or 256 h/a, from this paper. This doesn’t include mule time.

To say nothing of the fact that automation and optimization only kick in once you’re already producing at scale.

From this paper. The paper doesn’t quote the gap between free workers and slaves, but you can eyeball the graph to get orders of magnitude. It also mentions how slaves were not less productive than free workers, and might have been more productive. Also this paper’s abstract corroborates it.

Some could also be found in the North, but the prevalence was much lower. The Mason-Dixon Line, an early Free-Slave demarcation line, was also a malaria demarcation line: North of it, malaria didn’t prevail.

Excellent piece. The South was locked into a bad economy, but it also continued to promote this model despite the writing on the wall. When Anglos started to move into Mexican Texas, they started growing cotton there as well, bringing lavery along, and where aghast when Mexico abolished slavery in 1821. The reason for Texas' push for independence was, in good part, the growing pressure from the Mexican authorities to end slavery in Texas as well. "Freedom for Texas" meant Freedom to keep enslaving other human beings". Makes the Alamo look a lot less heroic...

Great article. I think far too many people underestimate the importance of geography and food production on modern history.

One additional cause of the different economic development between the North and South is the different types of people who settled in each region. The Puritans who settled in New England and the Quakers who settled in Pennsylvania came from relatively commercialized regions in England. Same for the Dutch who settled New York. Meanwhile the Cavaliers who settled in Virginia and the white slave owners from Barbados who settled in South Carolina were from more traditional agricultural regions with unskilled agricultural laborers.

I have no doubt that the differing geographies of each colony were part of the reason why they chose to settle in different colonies, but the type of society they left behind in England played an important role as well.

https://frompovertytoprogress.substack.com/p/why-european-settlers-in-north-america