How Bread vs Rice Molded History

I’ve been a bit delayed on articles the last couple of weeks. I will catch up in the coming days.

Bread vs Rice

What’s your staple, bread or rice?

This is a momentous fact, for it might have determined politics, culture, and wealth.

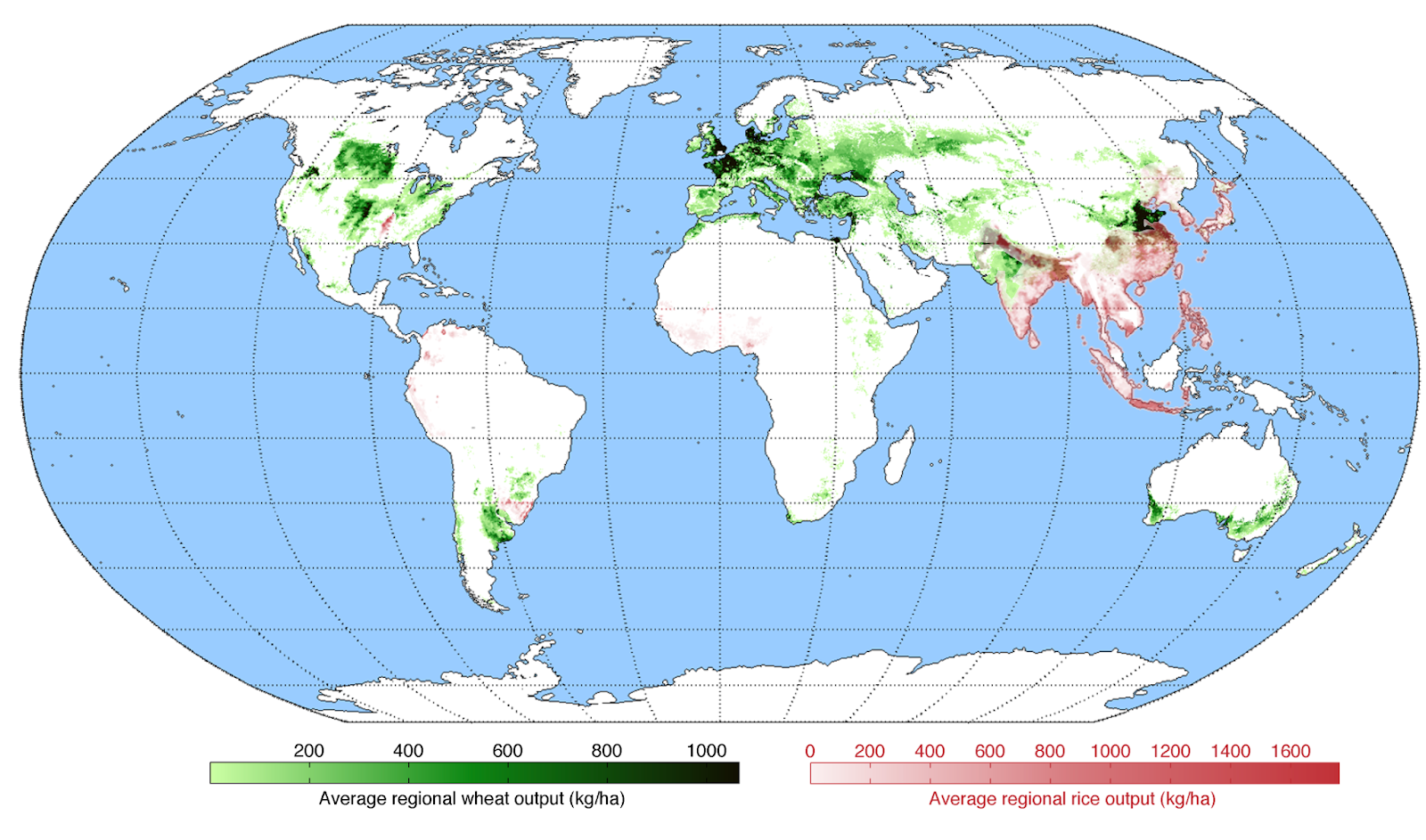

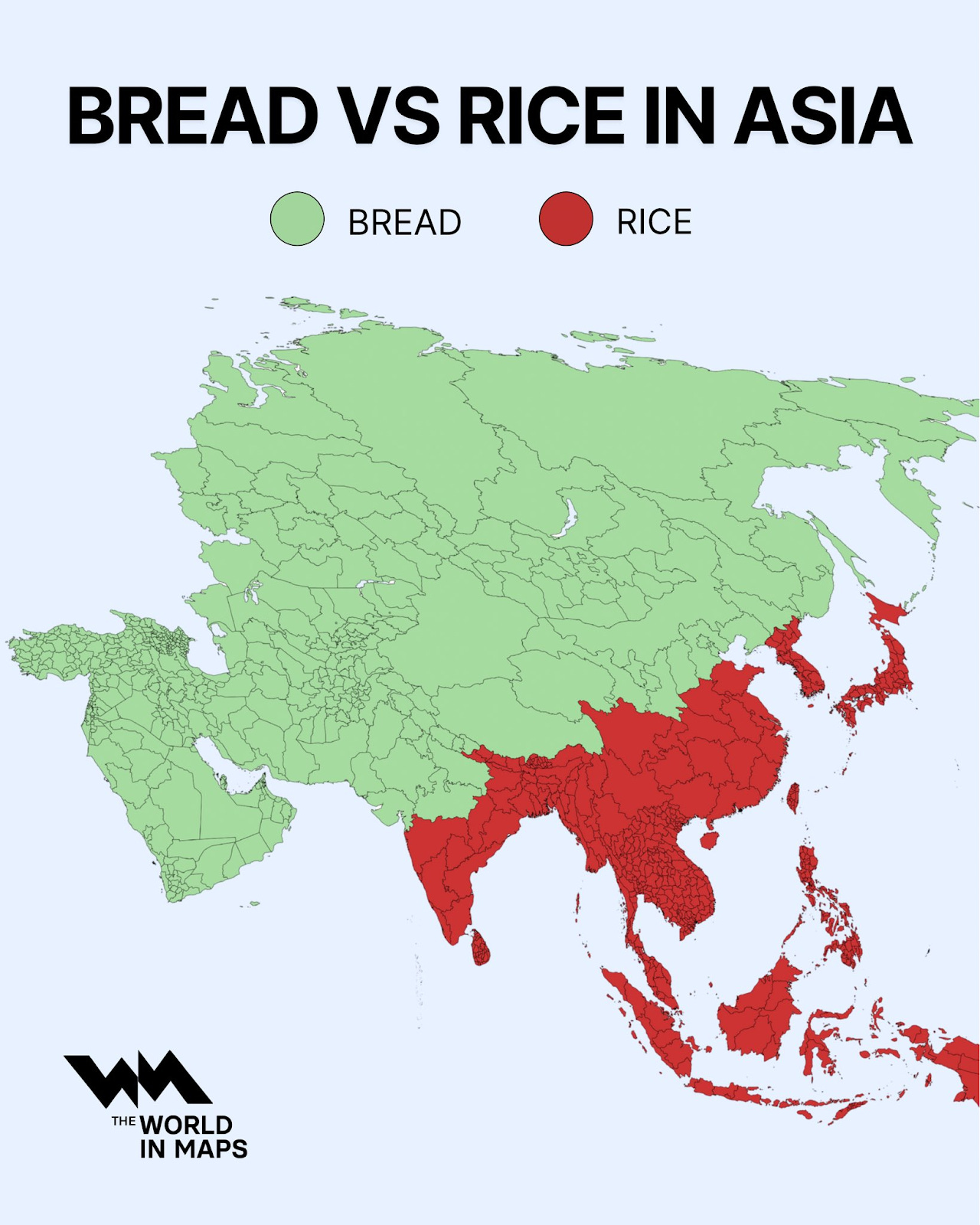

How? Well, bread comes from wheat, and rice from… rice. Here’s where they’re farmed:

Wheat and rice are not harvested in the same places. Rice and bread are the predominant food where rice and wheat are respectively the predominant crops. Here’s another way to look at the same data:

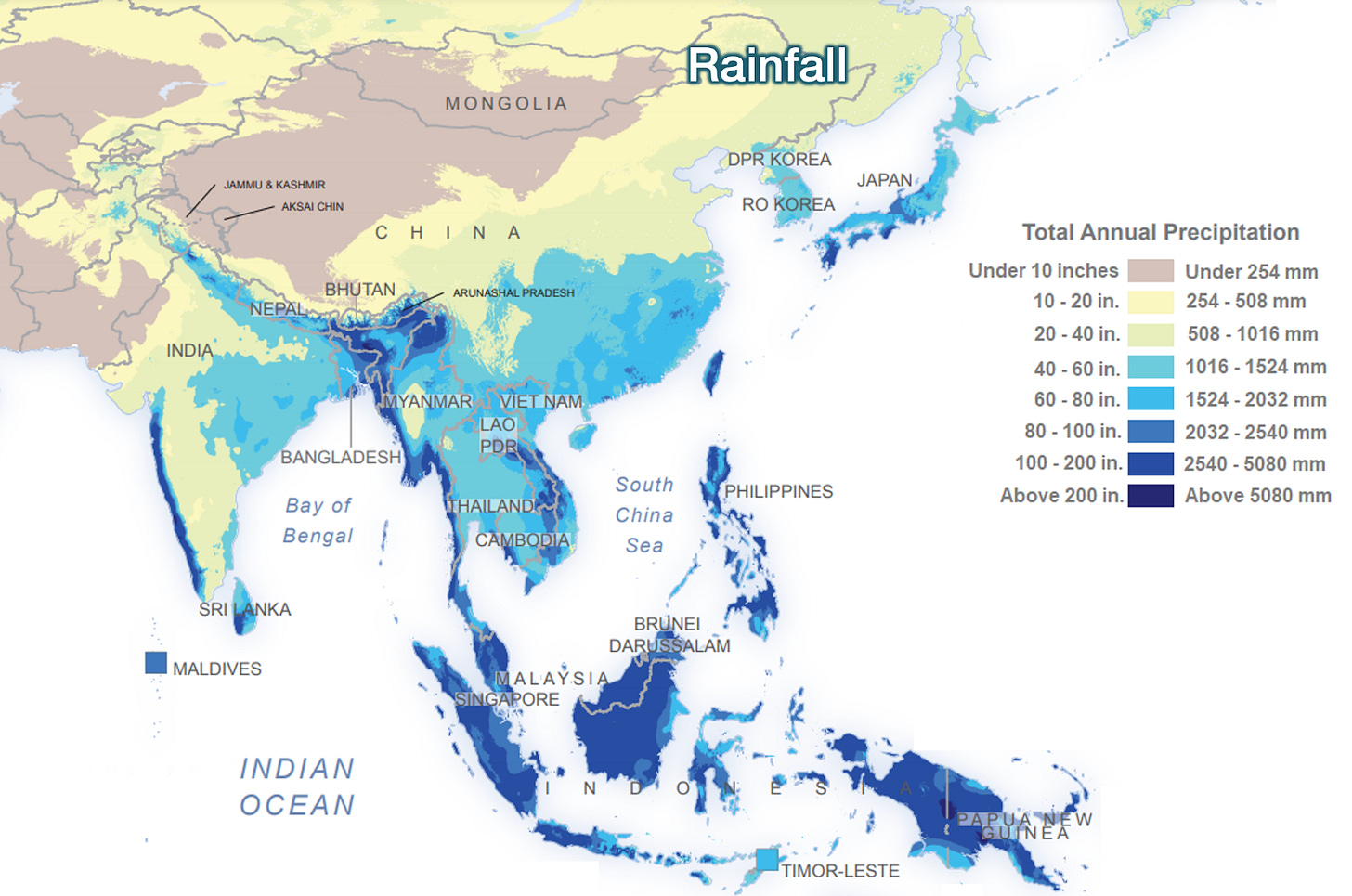

This, in turn, is determined mainly by this:

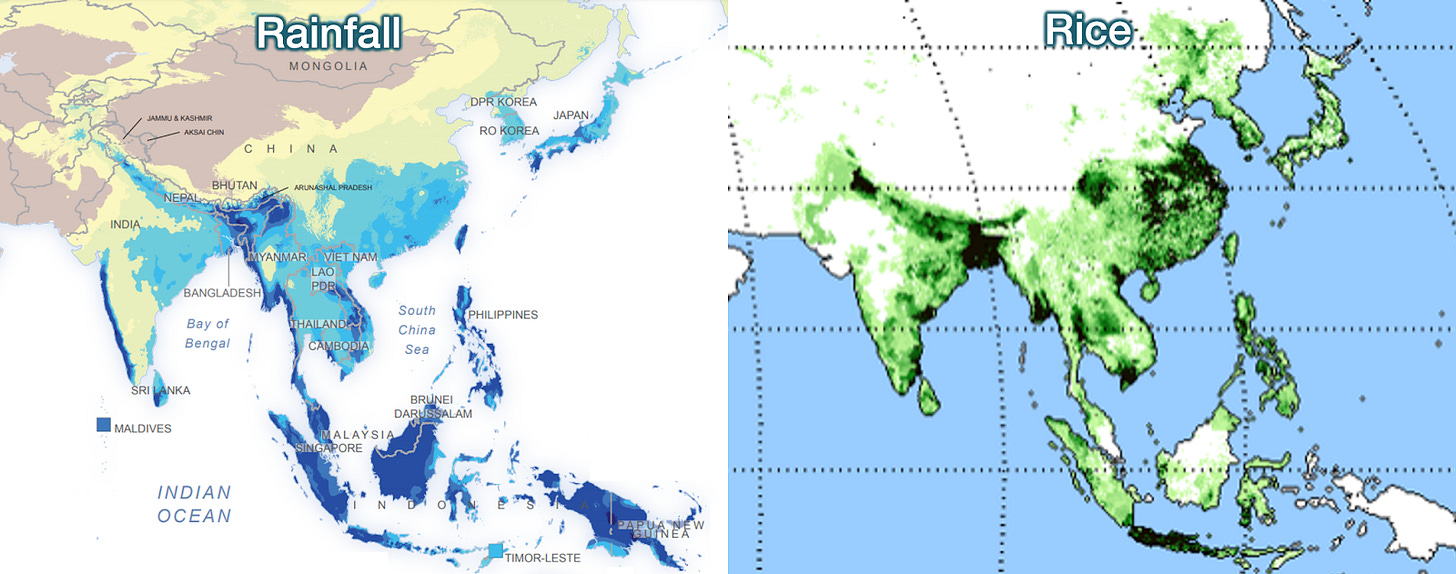

Rice crops vs rainfall, side by side:

But this doesn’t fully explain it since it also rains a lot in Ireland, for example, but nobody grows rice there. You need the heat found closer to the equator: Rice grows in hot, wet, flat, floodable areas, whereas wheat prefers cooler, drier, better drained areas.

Flooding rots wheat but can 3x the yields of rice.1 That makes wheat well adapted to hills, whereas rice can only survive on hills when they are terraced:

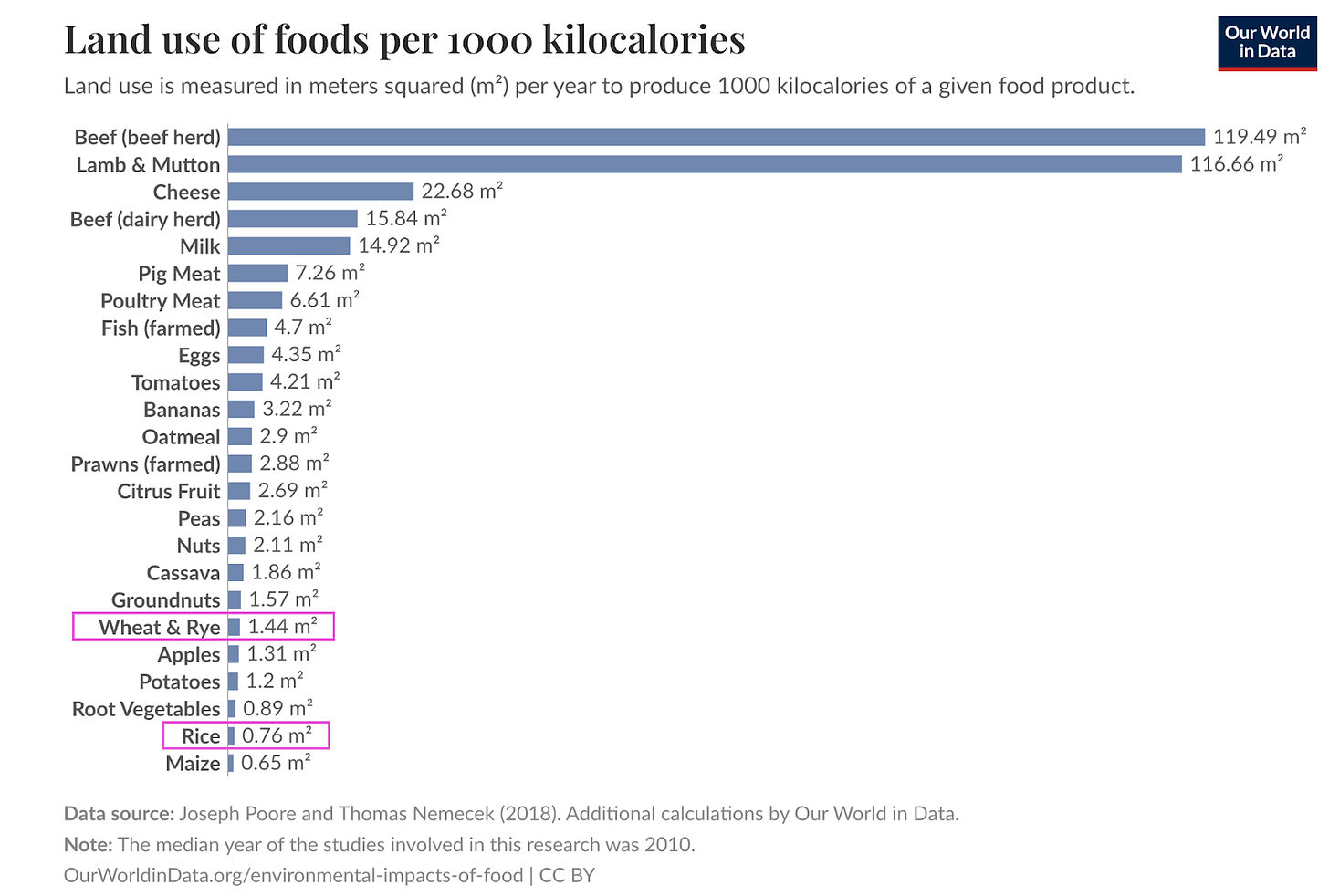

This sounds like just a fun fact, but it ain’t. Because rice generates twice as many calories per unit of area.

The Populations of Bread & Rice

This means that rice nourishes families on half the land that wheat requires.

Which means population density in rice areas can be twice as high as in wheat areas, or four times with double cropping.2 A hectare of land can feed 1.5 families with wheat and 6 with rice.

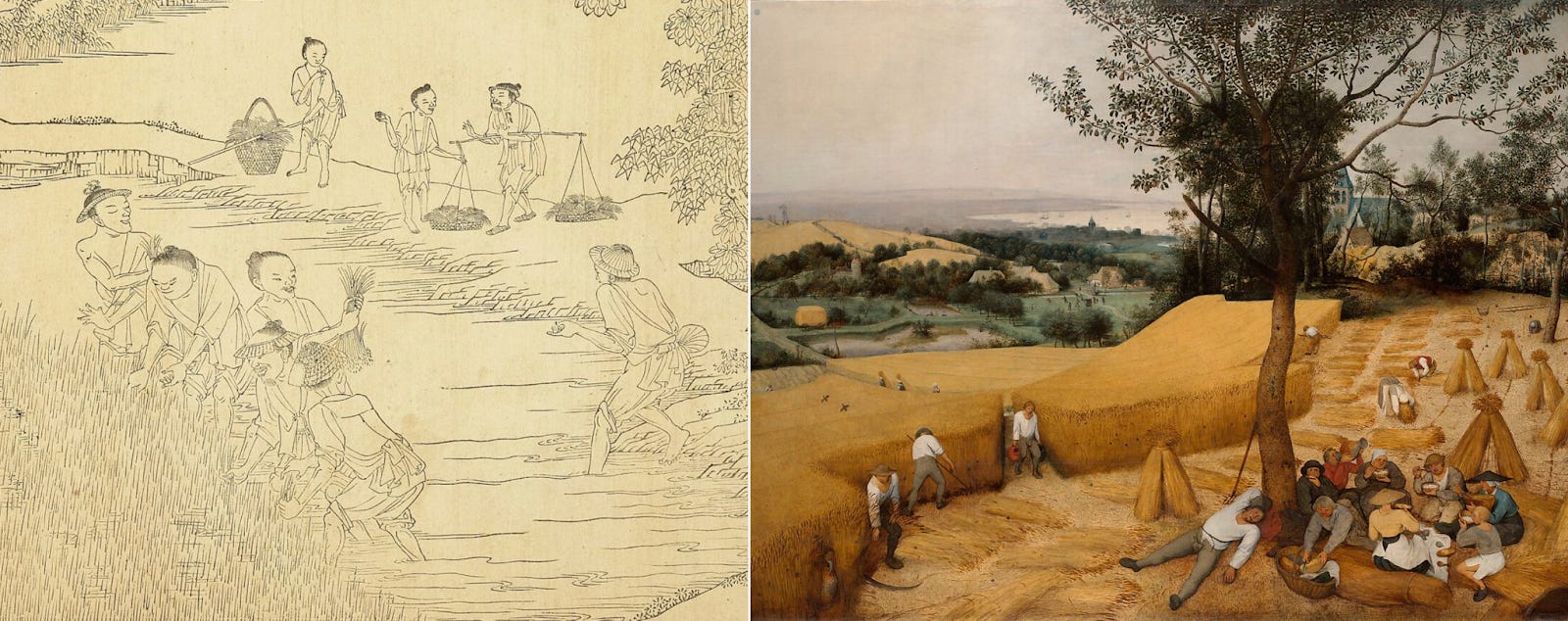

Yet rice paddies also require a lot of work—twice as much as wheat. And that work is almost year-round: preparing paddies, raising seedlings in nurseries, transplanting every single seedling by hand into flooded fields, managing water, pumping it,3 weeding,4 harvesting, and threshing—often followed by a second rice crop or a winter crop. These tasks peak during transplanting and harvest, creating critical seasons where a huge amount of work must be done in a short window of time.

Crucially, this labor cannot be delayed—if you miss the planting window or harvest late, the crop is ruined. As a result, rice farmers developed reciprocal labor exchange: neighbors help each other transplant and harvest in time. The timeliness pressure meant rice villages became tightly cooperative communities to ensure everyone’s fields were tended before it was too late.

"If one is short of labor, it is best to grow wheat" —Shenshi Nongshu (Master Shen's Book on Agriculture, 沈氏农书), 1600s.

Wheat farming historically had a more seasonal rhythm with periods of relative quiet. Wheat is typically sown in the fall or spring and then mainly just left to grow with the rain. Aside from episodic weeding or guarding the fields, there was less continuous labor until harvest time. Harvest itself was a crunch period requiring many hands with sickles—European villages would collaborate during harvest, and farmers might hire extra reapers.

These differences made these regions diverge across politics, culture, and economy.

The Divergences of Bread vs Rice

Political Divergence

The fact that wheat can grow just with rain means less investment in irrigation infrastructure, so individual families could fully handle their own fields. Decentralized states were the result of that, very obvious during Europe’s Middle Ages. That was not the case for rice, which required controlled irrigation and flooding, which means irrigation canals, dikes, reservoirs… all of which require collective effort. Neighbors upstream and downstream had to coordinate water usage; entire villages synchronized planting and flooding schedules. And let’s not forget the terracing. This can more easily give rise to hydraulic societies, highly centralized states that control and coordinate the irrigation system, as we saw in How Rivers Shaped States.5

Cultural Divergence

Maybe this made cultures more or less individualistic? Westerners are famously more individualistic than East Asians. Christianity emphasizes the value of every life and every soul, which leads to more individualistic societies that guarantee individual rights of property and life. Meanwhile, Confucianism, developed in China, emphasizes social duties, puts the interests of society at the forefront, and created societies that are much more sensitive to losing face. Could these differences be linked to crops? When your life depends on your relationship with your neighbors, you better develop a culture of group harmony, family loyalty, and consensus decision-making.

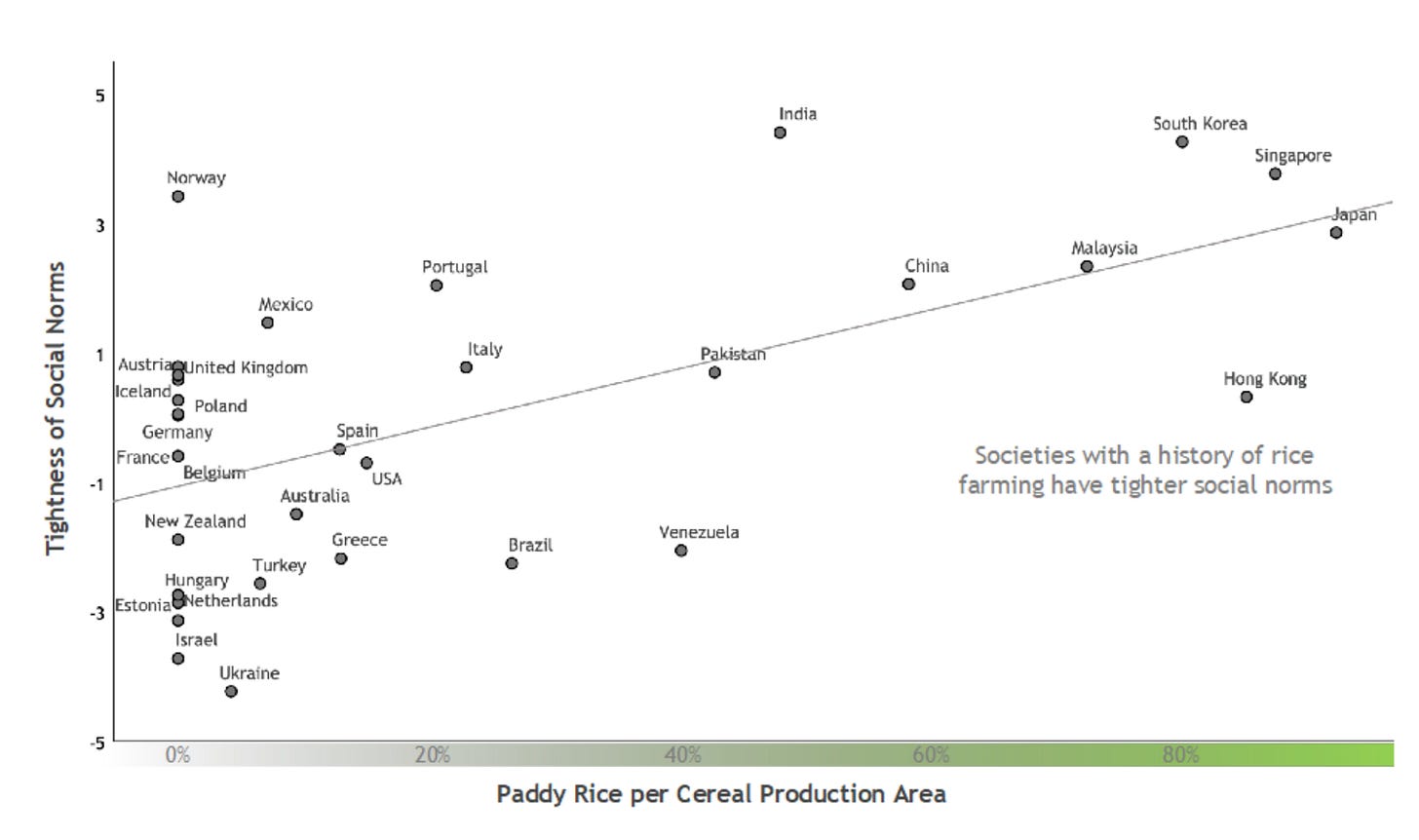

This is the Rice Theory of Culture. But is it true?

To test it, academics went to China,6 a country that is politically, religiously, linguistically, and ethnically uniform, but where the north has historically farmed more wheat and the south more rice. There, they found that:

In psychological tests, people coming from rice-farmed areas (“rice people”) were more culturally interdependent than wheat people (e.g., rice people self-inflate less).

Wheat people reason by focusing on individual elements, while rice people think more holistically.

Rice regions have tighter social norms than wheat regions.7

This comes with stronger social order, less crime, and less drug abuse in rice regions.

But also with less individual freedoms and less acceptance of immigrants. Rice regions are more likely to support authoritarian governments.

Outside of China:

Rice-farming nations had tighter social norms than wheat or herding nations.

People in rice-farming villages in Japan were more concerned about their social reputation than people in fishing villages.

Rice-farming societies tend to have less flexible, less mobile relationships.

Wheat people rate family as less important in life than rice people.

Wheat people are also more likely to think that parents have to earn respect from children, rather than respect being automatic.

Rice people treat their friends better but strangers worse than wheat people.

All this could just be correlation, not causation. Luckily, this paper found a quasi-random test, courtesy of the Chinese Communist government, who quasi-randomly assigned people to farm rice or wheat in two state farms that are otherwise nearly identical.

The rice farmers show less individualism, more loyalty/nepotism toward a friend over a stranger, and more relational thought style.—People quasi-randomly assigned to farm rice are more collectivistic than people assigned to farm wheat, Talhelm & Dong

Economic Divergence

Outside of harvest and planting, wheat farmers had more off-season time. This free time could be spent on other pursuits: tending livestock (common in wheat regions, since dryland grain and pasture were complementary), crafting tools or goods, or engaging in trade and markets during the winter off-season.

More importantly, wheat areas might have accelerated the Industrial Revolution and influenced the wealth of countries today.

When the Industrial Revolution really picked up, in the early 1800s, most available land in the Old World was already farmed. But not in the New World. Crucially, wheat doesn’t require many workers, so expanding farming in the US, Argentina, and Australia was extremely fast.

Since there was little land limitation, labor limitation really hurt, and that’s one of the reasons why American innovation massively contributed to farm labor automation: Automating the little work required could unlock thousands of square miles of new fields.

None of this was possible in the Old Worlds of China or Japan. The areas that could be opened up to rice farming, like in Thailand when new canals opened up the heartland, did get rice farming. But there, the requirement of labor was so massive that it was quite slow. Many Chinese farmers moved there, but that was not enough. The amount of automation needed to unlock lots of rice farming was too high. It was also much harder work to automate, as machines don’t easily deal with mud. All this meant that mechanization of rice farming came much later, that rice production didn’t increase that fast early on, that when it did it couldn’t easily fuel a new class of rich farmers, and that it did not locally accelerate the need for automation early on.

Takeaways

Wheat grows in drier, colder areas than rice and requires much less labor, but also produces less calories per unit of land than rice. As a result, rice areas had:

More population density

Stronger centralized states

A psychology and cultures that foster social harmony and collaboration

Meanwhile, wheat encouraged the colonization of the New World, allowed it to grow its wealth through farming fast, and accelerated the development of the Industrial Revolution, which increased the economic divergence between wheat and rice areas.

In other words, climate determined crops, which then heavily influenced our societies. Even decades after most of us have stopped farming, these effects carry into our subconscious cultures.

Does this mean these crops fully determined the history of the world? No. But they nudged it in a particular direction, like dozens of other factors that we explore in Uncharted Territories. The world is made of systems that mold us in certain ways, unbeknown to us. It’s only when we realize these influences and systems that we can reclaim them and decide where we want to take humanity.

Via this article: Dryland rice produces 1.2 tons per hectare, but flooded rice produces 5 tons (Khush, 1997). And of course, flooding eliminates weeds.

Double cropping was possible after the introduction of the Champa Rice variety, during China’s Song era, around 1000 AD. I am now connecting the dots and realizing that the population explosion that happened in China around that time, which we discussed in this China article, was at least in part caused by the introduction of this variant, as double cropping would allow for twice the amount of grain harvested! That also made the Song possible (as they only controlled the southern part of China). This population boom also caused the need for currency, which the Song solved by inventing paper money!

This great article mentions that pumping water was sometimes done by pedaling, and could take as much as 70 hours per worker. Fun fact, I once spent a summer in Burma trying to sell water pumps to farmers. We ended up building a microfinance institution.

Flooding reduces weeds, but doesn’t eliminate them all. And weeding underwater is much harder to do.

These societies were more common in high density areas like China than in low-density ones like Thailand. Also, as we saw in the article linked, it’s not the case that irrigation meant hydraulic societies. Egypt was one, whereas upstream Mesopotamia was not, because the ability to predict harvests in Egypt made taxation easy. I assume in the flat and heavy-rain areas of the Ganges, Yangtze, Yellow, Red, Irrawaddy, Mekong, and Chao Phraya river valleys, production was easy to predict, so taxation could be effectively executed, and it would lead more consistently to hydraulic societies than in the less predictable Mesopotamia. But I don’t know, so take this with a grain of salt.

This Reddit comment posits that millet was likely a more prevalent crop in China in antiquity. I don’t think it changes much, because from what I can gather, millet’s requirements and growing regions are similar to wheat’s, and northern China is mostly a wheat and bread region, while southern China is the rice country.

This is not the only, or even main determinant of tightness. Others like external threats are stronger.

Fun reading, thank you! But I would suggest you redact this sentence: “country that is politically, religiously, linguistically, and ethnically uniform,….” China is no more uniform than Spain…… maybe it’s less uniform than Mexico, but not by much….. lots of religions and cult practices exist underneath the surface as well as Taoism and historic Buddhism as well as Confucianism and lots of different language groups. Most of them are same language family as Han Mandarin but certainly Cantonese is not mutually intelligible and there’s many other languages that are similarly different.

This argument is also examined at length in the French historian Fernand Braudel's "Les Structures du Quotidien" (volume one of Civilisation matérielle, économie et capitalisme). He makes most of the same points, and extends the reasoning to maize (corn) in the new world. Traditional maize crops also yield substantial calories per hectare, but require even less work than wheat, so you have a well-fed, healthy population with time on its hands. Your land use graph above makes this point implicitly. I'm not sure the dots connect as well as they do for rice and wheat - the influence of the Black Death on labor availability in the 15th century bears mention as well - but it's definitely interesting.

I think potatoes might have been the real game-changer anyway, but those became widespread much more recently, because they originate in the new world. But they are historically cultivated in ways that are complementary to other crops, such as raised beds in Ireland prior to the famine in the 1840s. The Irish ate as much as ⅔ of their calories from potatoes in the 1830s and were among the healthiest people in Europe. This dependence is why the famine hit them so hard.