How Elon Musk Defies the Laws of Gods

How He Decides on Vision, Strategy, Products, and Marketing by Reasoning from 1st Principles

I’m trying something new today: I’m combining both the free and premium articles into a single one with a paywall. Let me know what you think!

If the email is too long, Gmail will clip it. Click on the title to read it on web!

Elon Musk is TIME’s person of 2021.

As TIME puts it:

The richest man in the world does not own a house and has recently been selling off his fortune. He tosses satellites into orbit and harnesses the sun; he drives a car he created that uses no gas and barely needs a driver. With a flick of his finger, the stock market soars or swoons. An army of devotees hangs on his every utterance. He dreams of Mars as he bestrides Earth, square-jawed and indomitable. Lately, Elon Musk also likes to live-tweet his poops.

Famously, Musk is known for reasoning from first principles, as opposed to reasoning from analogies. This reasoning is what has led him to where he is: why he focuses on what he does, and why he succeeds at it. So let’s first understand 1st principles vs. analogies, and then we’ll see how Musk applies them.

Analogies vs. 1st Principles

Analogies

Our ancestors didn’t know the Earth was a rock in space orbiting the Sun. But they knew the sun was going to come up tomorrow: it had done so every day for as long as they could remember.

Our ancestors didn’t understand nutrient absorption. But they knew herbivores would keep grazing, carnivores would keep hunting them, and herbivores wouldn’t hunt carnivores back. These rules had been in place for as long as they could remember. They weren’t going to change.

Romans couldn’t calculate whether a new structure would stand or crumble. They didn’t know about material tensility. With their numbers system, they barely even had math1. And yet some of their structures are still standing to this day. They had noticed which ones remained standing and which ones crumbled, and kept applying those learnings.

Most of our knowledge is based on analogies. We look at what has happened in the past, we generalize the rule, and we apply it to the future. From Merchants of Risk:

In many industries, people study precedents well: doctors learn from previous cases, lawyers look at jurisprudence, soldiers study the history of war...

Other industries have learned to do that more recently. For example, now you have 724 Marvel Universe movies because they are proven to work, there are precedents that they will make money.

You’ve probably heard adages like Don’t reinvent the wheel or Steal like an artist. When something works, adopt it. Don’t question it.

This is what we do for most things in life. We look at how others do things, what happens then, and we just do the same thing.

But sometimes, applying what’s already proven doesn’t work. Or it could work much better. What do you do then?

1st Principles

Under 1st principles, you go down to the building blocks of the world, to fundamental rules that govern everything. From there, you rebuild the entire tree of knowledge, reasoning step by step everything humans take for granted. In the process, many of the conclusions you reach will be the same as other humans. But in a few cases, you might realize most humans were wrong, and that’s where you find room to innovate, to be right where others are wrong, and to take advantage of that arbitrage opportunity.

This is an example of 1st principles applied to architecture:

“An analogy: to go from medieval castles to skyscrapers, we don’t just iterate on stone towers; we leverage fundamental scientific advances in both materials and structural engineering. That includes testing out structures as needed to check that the theory actually works, but the goal there is understanding, not just making tall test-towers. Tall towers might provide useful data, but they’re probably not the most useful investment until we’re near the end-goal. Most of the iteration is on e.g. metallurgy, beam loading under controlled conditions, not on tower-height directly.”—johnswentworth, The Plan

In 1st principles, you don’t have certainty: you can go back to 1st principles and revise one of your conclusions based on new information. Black or white doesn’t exist anymore, it’s all shades of gray.

This is what science is. It’s not a series of conclusions about the world. It’s a way of thinking. In science, gravity is true until it’s proven false, and general relativity is right. Then relativity is proven wrong by quantum mechanics.

Reasoning from 1st principles seems exhausting. You need to rethink everything you’ve ever heard from scratch? And if you were wrong in a deep part of your tree of knowledge, you need to revisit the entire branch structure rooted in that flaw?

It isn’t as exhausting as it seems. There is a lot of work to do when you discover a new field of knowledge, but that is fascinating work! Finally figuring out the way the world really works. Then, you simply need to be humble enough to realize that you can always be wrong. When you do find one way in which you’re wrong, that’s great! You get to build a better model of reality.

What’s the Benefit of 1st Principles?

Musk explains 1st principles like this:

I think generally people’s thinking process is too bound by convention or analogy to prior experiences. It’s rare that people try to think of something on a first principles basis. They’ll say, “We’ll do that because it’s always been done that way.” Or they’ll not do it because “Well, nobody’s ever done that, so it must not be good.” But that’s just a ridiculous way to think. You have to build up the reasoning from the ground up—“from the first principles” is the phrase that’s used in physics. You look at the fundamentals and construct your reasoning from that, and then you see if you have a conclusion that works or doesn’t work, and it may or may not be different from what people have done in the past.

In science, this means starting with what evidence shows us to be true. A scientist doesn’t say, “Well we know the Earth is flat because that’s the way it looks, that’s what’s intuitive, and that’s what everyone agrees is true,” a scientist says, “The part of the Earth that I can see at any given time appears to be flat, which would be the case when looking at a small piece of many differently shaped objects up close, so I don’t have enough information to know what the shape of the Earth is. One reasonable hypothesis is that the Earth is flat, but until we have tools and techniques that can be used to prove or disprove that hypothesis, it is an open question.”—Elon Musk, The Cook and the Chef, WaitButWhy2

One way Steve Jobs put it:

When you grow up, you tend to get told the world is the way it is and your life is just to live your life inside the world. Try not to bash into the walls too much. Try to have a nice family life, have fun, save a little money. That’s a very limited life. Life can be much broader once you discover one simple fact. And that is: Everything around you that you call life was made up by people that were no smarter than you. And you can change it, you can influence it, you can build your own things that other people can use. Once you learn that, you’ll never be the same again.

Nobody knows anything, including you. That is liberating: you can question everything, and see for yourself who is full of it. That then allows you to innovate.

When most people cook, they just follow recipes. Since we don’t quite understand why the steps are what they are, in that order, and with those ingredients and quantities, we follow them blindly. Our experience tells us that if we don’t do that, our food is going straight to the dog. That’s being a cook.

Not everybody cooks that way. Some people gather enough experience that they start recognizing patterns. They realize butter can be replaced with oil, the heat doesn’t need to be that high if you cook for longer, etc. These are still cooks, but they’re figuring out a few things on their own.

If you push that to the extreme, you get the chef. A person who doesn’t follow recipes. She understands what the recipes are trying to do, knows the underlying chemistry, and can invent something completely new from the ground up. The chef, of course, thinks in 1st principles.

If you use this metaphor for life, this is what you get:

Those who go deep to understand the underlying drivers of a discipline can then innovate, create from scratch, rethink everything. They can reach limits nobody else reached before them.

That’s the benefit of thinking in 1st principles.

The Danger of 1st Principles

But being a cook is easy! Just take a recipe and follow it. You can forecast that the recipe will work because it has worked for others. And if you do it once well, you have an even better precedent, and can increase the confidence of your forecast for the next one. In other words, you can predict a good dish coming from a recipe that you’ve tried and enjoyed.

Upgrading from cook to chef takes years of studying and experience. Only then, once you know the fundamentals, can you innovate, can you come up with new concoctions that you can forecast with confidence will work.

So this is the first danger of 1st principles: it takes years to practice, and if you’re overconfident, you’ll apply bad 1st principles and perform worse than with analogies.

For example, the fields of mathematics and physics are full of first principles. We have a good sense of the core laws. But in medicine, we know very little. Most of what we know is empirical: “We tried this, it worked, we tried it again, it worked again, so we assume it will keep working.” This might be somewhat informed by first principles, but it’s mostly reasoning by analogy. Those who only reason with 1st principles in medicine might come up with theories that are completely off. Those who then follow them are much more likely to make mistakes.

In many industries, where you’re dealing with very complex phenomena, you don’t really understand them, so you’re better off simply doing again what has already worked. Areas like biology, psychology, or sociology are good examples.

Precedents are especially useful in complex, chaotic situations that are hard to understand. Look at COVID: one and a half years in, and there’s still debate around masks, vaccines, lockdowns, treatments… If you go into the detail of each one of these debates, the nuances are indeed quite complex. Studying it all is awfully hard. But you don’t need to go into all this nuance. If a bundle of policies works over and over again, you can adopt the bundle wholesale as your starting point.

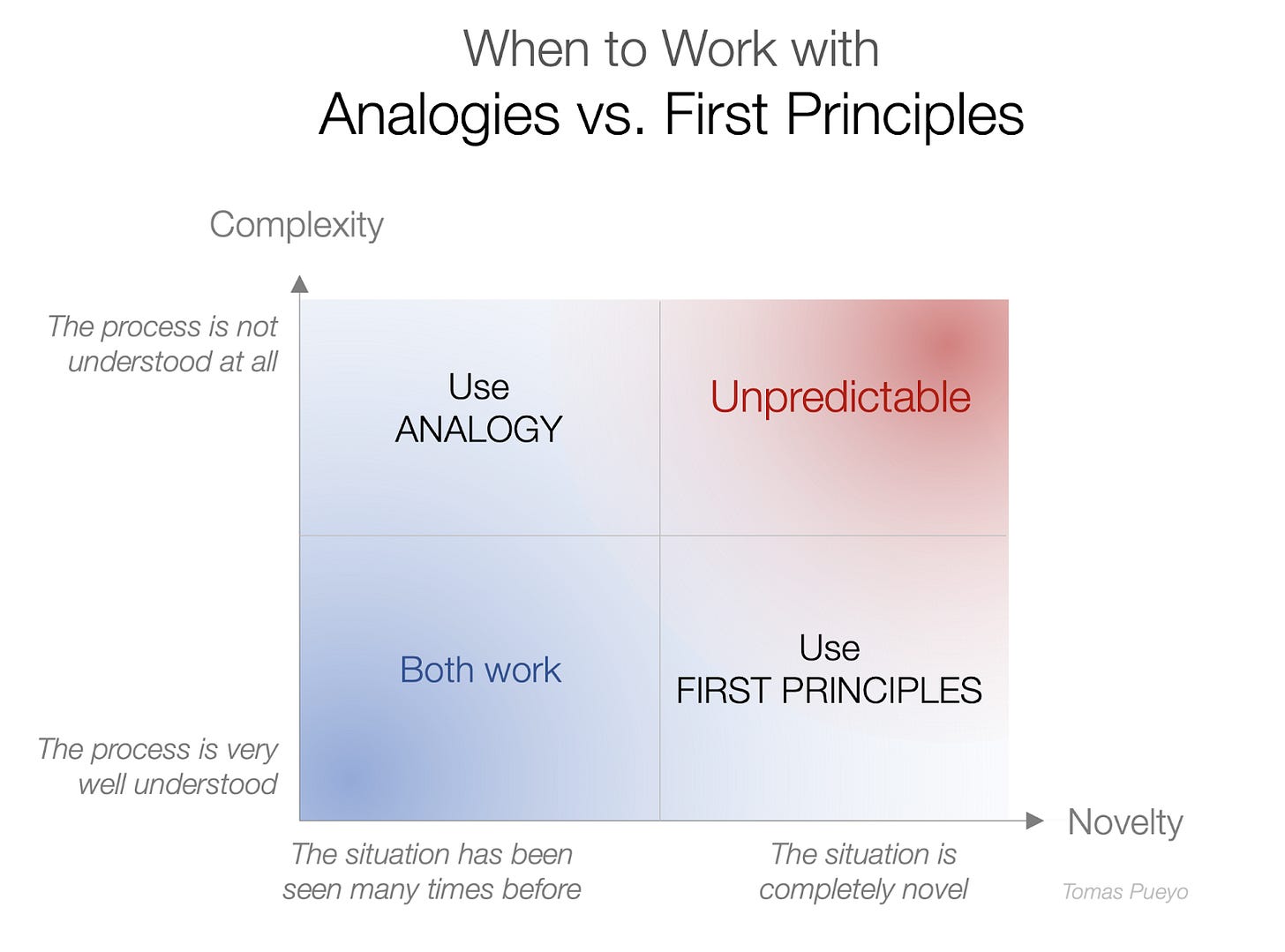

If something is very repeatable and so complex that you don’t understand it well, use analogies.

If a situation is novel but you understand its drivers really well, you can apply your 1st principles rules.

The best thinkers are not dogmatic. They do both. They usually start with analogies to get the lay of the land. Then, they go deep to understand where they can apply 1st principles instead. As they develop their 1st principles, they reach useful conclusions but also figure out their limitations. They apply analogies in the areas where they don’t fully grasp the 1st principles.

They will also compare both results, those from analogies and those from 1st principles. If these results are aligned, then their confidence in their conclusion increases. If not, then they need to understand why. Time to study more.

Reasoning from 1st principles is then dangerous and hard. But if done well, it can bring benefits others can only dream of. This is what Musk has done. How has he applied his 1st principles specifically?

How Elon Musk Applies 1st Principles to His Priorities

In this section, we’ll learn how Musk has used 1st principles to pick the companies he wanted to build3, and how he’s used 1st principles to create the right strategy, amazing products, and successful marketing campaigns.