GeoHistory Magazine | Q2 2025

Each quarter, we apply the UT lens to the world’s chaos to extract clarity. Today, we’re looking at all the interesting GeoHistory themes that have emerged recently. This is not meant to be read cover to cover, but rather for you to jump to the topics you’re most interested in. Today:

The Economics of Space

Starbase

Trade Wars

Phantom Maps

Druzes vs Syria

Forgotten civilizations in the Sahara?

A humorous and revealing map of Brazil

The volcanic fall of the Roman Empire

Poland vs Russia

English as the Lingua Franca of the world

Mountains vs flatlands

Why do we see what we see, and not other types of light?

An 11 meter painting that reveals a lot about China’s past

Influencer strategy, 120 years ago

We were right about global taxes

The Economics of Space

In No Room for Deep Space, we saw that the economics of space mining are quite bad, because there aren’t that many rare minerals easily accessible in space, and space mining is too expensive. If there were a very valuable element to mine in space, its quantities would need to be such that it would flood the market, crashing prices, and making the entire venture senseless. We saw a good example of this recently.

As far as I can tell, the original source of this claim is this Forbes article, which quotes no source or calculation. My interpretation is that scientists claim this is mostly a metallic asteroid with 10 quadrillion tons of mass. To give you orders of magnitude, that’s about 10 million years of iron production on Earth.1

Journalists speculate that if we brought this asteroid back to Earth, the quantity of metal available would be of gargantuan value: Iron is worth $424 per ton, nickel $14k, and gold $75M, so as long as it’s mostly metal, the asteroid would be worth many quintillion dollars, regardless of its composition.

At current metal prices.

But of course, these metal prices would crash if we had such an asteroid available to mine. In fact, if it were indeed very high grade ore, virtually all metals it contains would become nearly worthless overnight.

That said, this makes me think this could actually be a valuable project for the world, if we figured out a cheap way to get this metal to Earth. Yes, those metals would become worthless, making the venture a money-losing proposition, and killing many mining industries in the process. But what would happen next?

Nearly all products that use these elements would suddenly drop in price. Across the world, many expensive things would become cheap, as their cost converges towards that of energy and logistics. Demand for these cheaper products would skyrocket. It would usher in a new era of abundance. What would that look like?

Steel would become even more ubiquitous. Housing would contain much more steel. Big infrastructure like bridges, electric grids, ships, robots, rockets, and airplanes would drop in price. Mining would shrink, and with it, its ecological footprint.

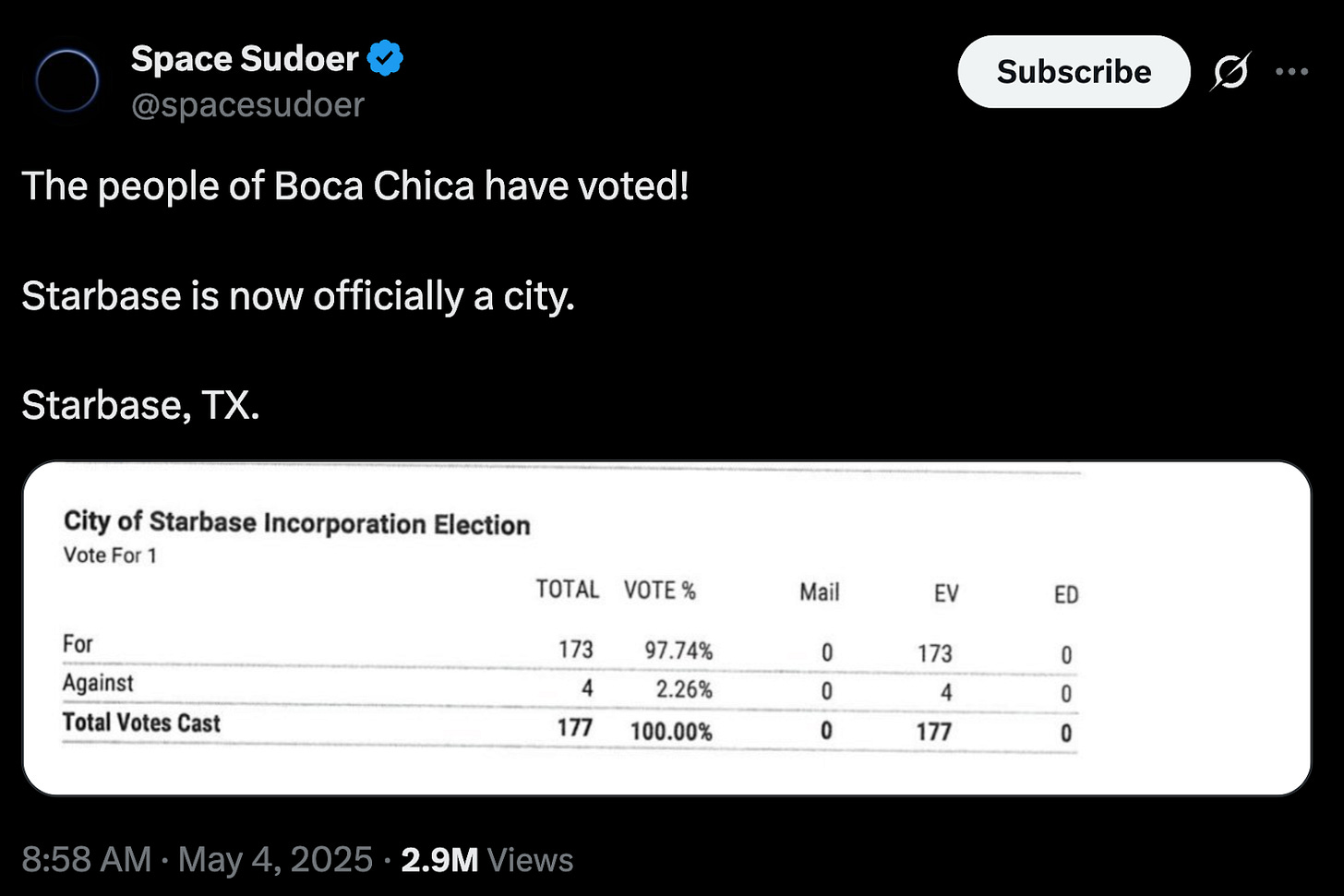

Starbase Is Now a City!

Since we’re talking about space: On January 16th of this year, we said Boca Chica should become a city. It became one in May!2

Trade Wars

The Japanese Mistakes that China Avoids

In What Asian Development Can Teach the World, we discussed how Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea navigated the world economy after 1945 to become rich countries. There were three key strategies:

Redistribute land so that farmers are owners, care more about the output, and farming yields increase.

Support and protect core private industries, under the condition that they must win in internationally competitive markets. Kill the companies that can’t win internationally.

Intervene in financial markets so that people’s savings are used to finance point #2. Liberalize them little by little, once the industrial giants are well established and the economy can compete globally. Avoid too much debt and too much consumption.

Very clearly, China has been following this path. This is why Chinese people can’t invest abroad, why the stock market there is stifled, and why the government let the real estate bubble collapse, while at the same time propping up industries like drones, batteries, and solar panels. Internal consumption used to be discouraged.

In this interview, Kenneth Rogoff (the former Chief Economist of the International Monetary Fund) highlights what happens when you have 1 and 2, but too quickly move to #3. This happened to Japan when it signed the Plaza Accords in 1985. Seven years later, Japan’s real estate and stock market bubbles burst, the country plunged into a generational crisis, and Japan has not recovered since.

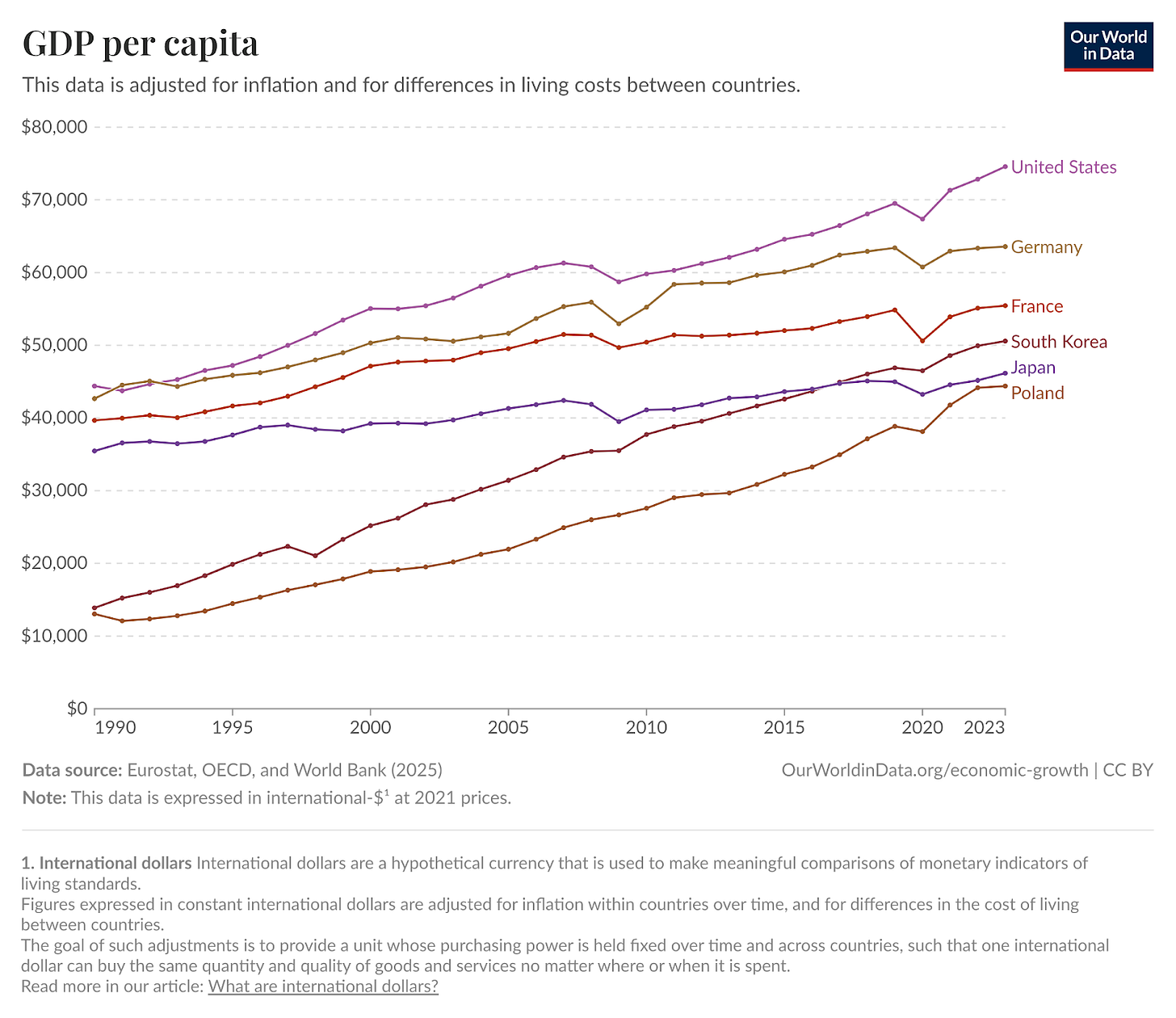

According to Rogoff, Japan could be 50% richer than it is today if it hadn’t followed that path. A country that was richer than the US will soon be poorer than Poland.

What happened? The Plaza Accords came from US pressure on Japan to strengthen the Yen quickly. Otherwise, Japan was exporting too much; it was too competitive. The US also pressured Japan to liberalize its financial markets.

The yen doubled in value in three years. This caused a trade reversal, with exports crashing and imports spiking, and lots of companies suffering heavily. To offset the economic shock, Japan slashed interest rates and flooded the economy with cheap credit.

This meant that Japanese banks had plenty of cash and a liberalized market; they went on a lending spree. They poured money into real estate and stocks with little risk assessment. Japan's stock market became worth more than the US stock market despite having half the population. The total value of Japanese real estate was 4x that of all US real estate!

When the bubble burst in 1991, banks were left with massive amounts of bad loans. The entire financial system crashed, creating a "lost decade" of deflation and stagnation, and Japan has yet to fully recover.

This is helpful context for understanding the trade war between the US and China, and why China doesn’t want to increase the value of its currency. That’s probably one of the reasons why the US prints a lot of money, in a process that depresses the USD’s relative value and boosts its exports.

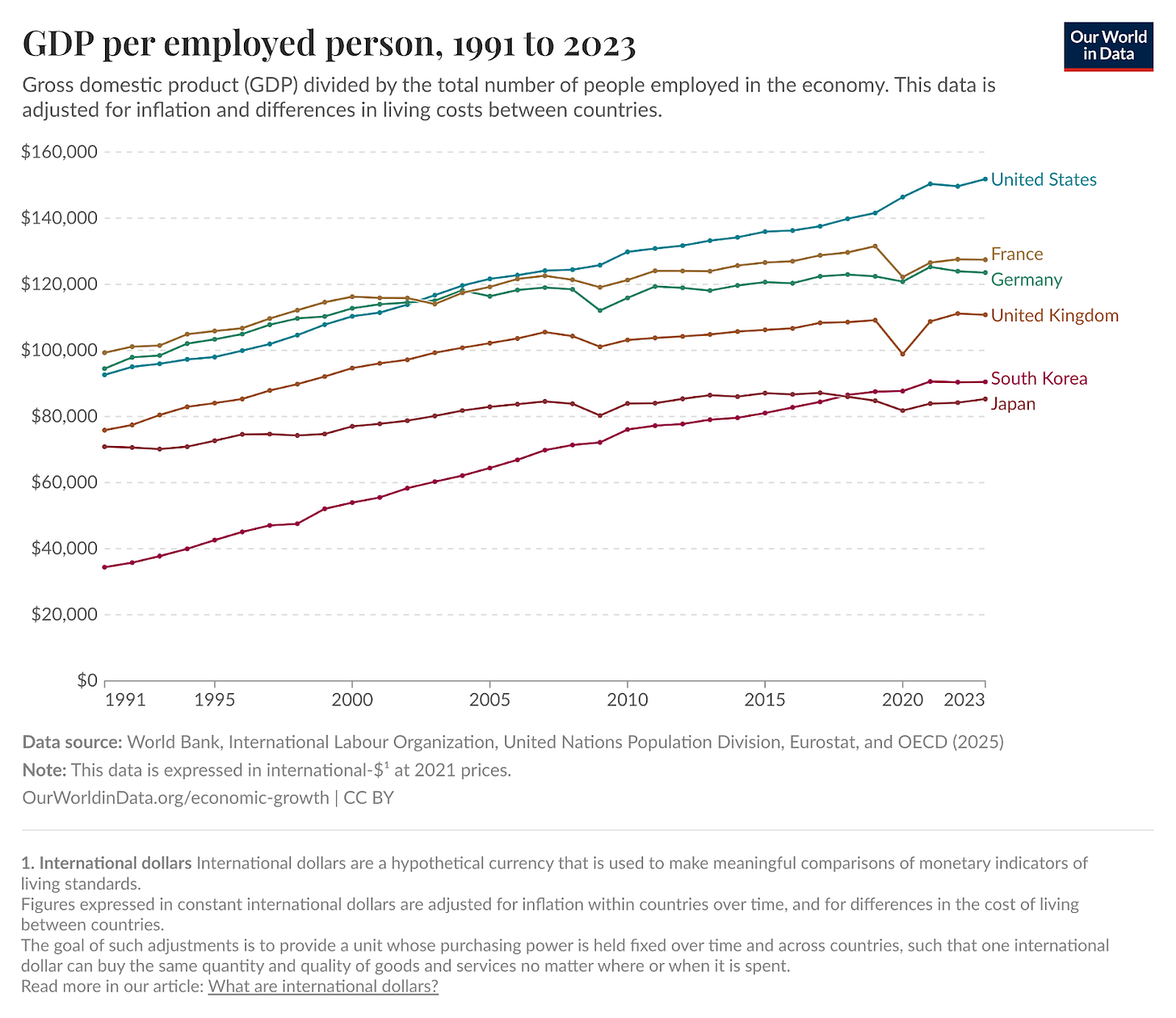

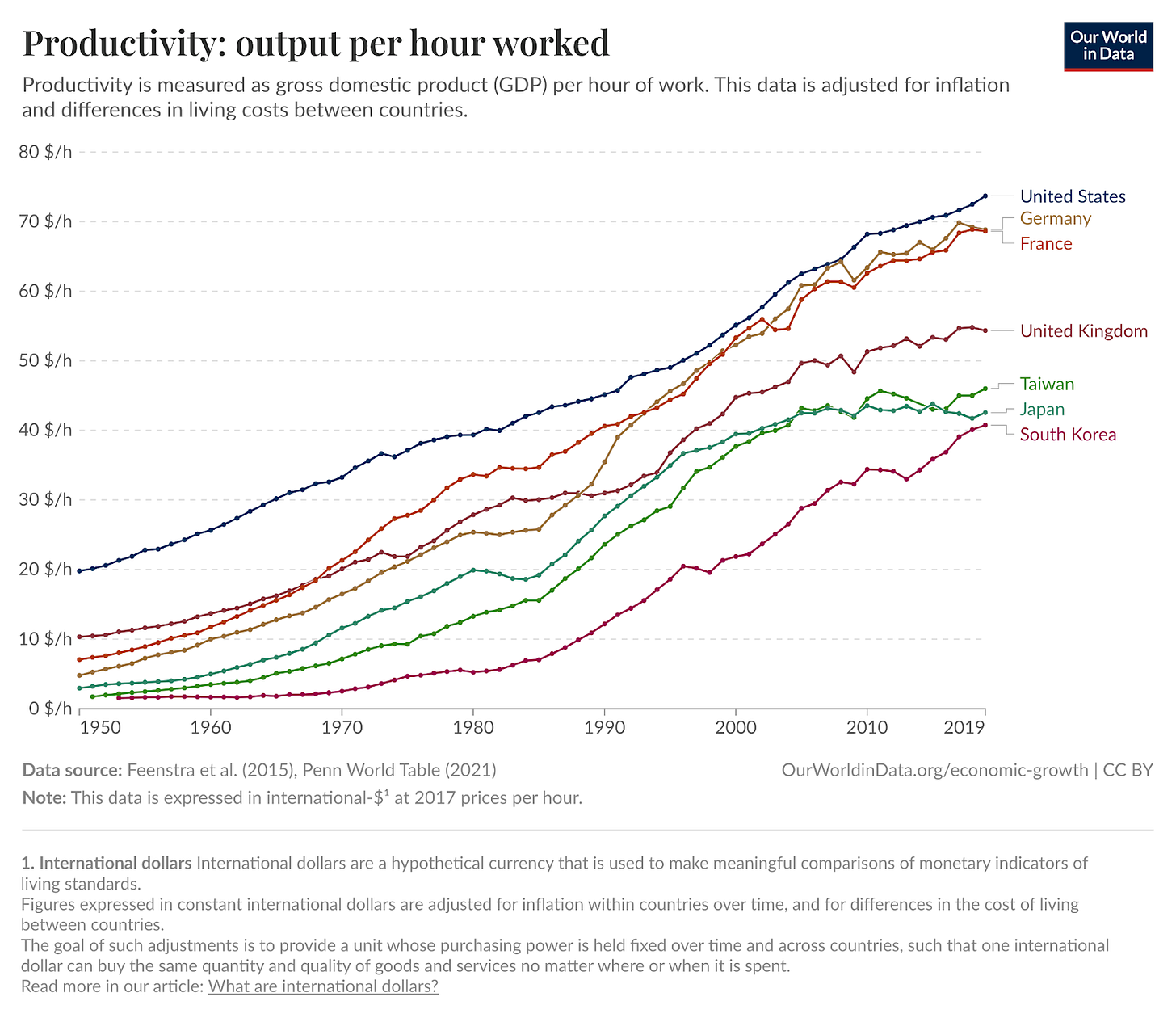

And this is not just a fertility or aging issue; Japanese workers are just less productive:

Even if you only look at productivity per hour worked:

Do Tariffs Work?

One of the tools Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea all used to protect their industries was tariffs. But this is easier said than done: Tariffs can cause a lot of harm. Did these countries’ tariff approaches work? Or did their economies grow despite them?

These countries prioritized infant industry protection, to protect young but important industries. Their governments had used the example of Germany and the US, which had used tariffs just as they had heavily industrialized. But according to this paper, tariffs didn’t help. Instead, they generally:

Reduced labor productivity

Made more, smaller companies

Raised prices

Employed more people

Created more value internally

How? By weakening foreign competition, more local companies could exist, create value, and employ people, but that’s because companies that weren’t very productive could survive. This lack of productivity was reflected in higher prices.

My shallow take on all of this is that protectionism for defense and infant industries is still valuable, but should be avoided for others. It also means that it makes sense to tax downstream products rather than upstream:

Don’t tax things like ore, steel, cement, or heavy machinery, unless you want your country to develop it (whether for geopolitical or economic reasons).

The closer a product is to end consumers, the more sense it makes to levy tariffs:

They hinder consumption (so people do more saving, which can be reinvested in growth)

They don’t hurt other industries downstream

Phantom Maps

We’ve done phantom maps of Poland and Germany. I stumbled upon this phantom map of ex-Yugoslavia, showing how illiteracy strongly correlated with Ottoman control:

Did mountains influence Ottoman presence, which in turn determined literacy?

Next:

Druzes vs Syria

Forgotten civilizations in the Sahara?

A humorous and revealing map of Brazil

The volcanic fall of the Roman Empire

Poland vs Russia

English as the Lingua Franca of the world

Mountains vs flatlands

Why do we see what we see, and not other types of light?

An 11 meter painting that reveals a lot about China’s past

Influencer strategy, 120 years ago

We were right about global taxes