What Asian Development Can Teach the World

The Magic Development of Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and China, and What That Tells Us about US Tariffs, China’s Future, EU Protectionism, Japan’s Zombie Debt, Southeast Asia’s future, and More

I’m planning a trip to Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and Singapore. I would love to meet with academics, business leaders, cultural leaders, and politicians, to understand the countries better and portray them accurately when I write about them. I’m especially interested in South Korea and its recent cultural explosion. If you are such a person or know someone I should talk with, please reach out by sending me an email (reply to this newsletter), DM me on Twitter, or fill in this form!

This week, I decided to merge both my articles into one. Enjoy!

A couple of weeks ago, we talked about why Japan’s economy hasn’t been growing lately, most notably because of its zombie loans. But their existence is linked to why Japan is rich in the first place. If you understand this, you can understand a lot of why some Asian countries are rich while others are poor—and see how this might apply to other countries in the world.

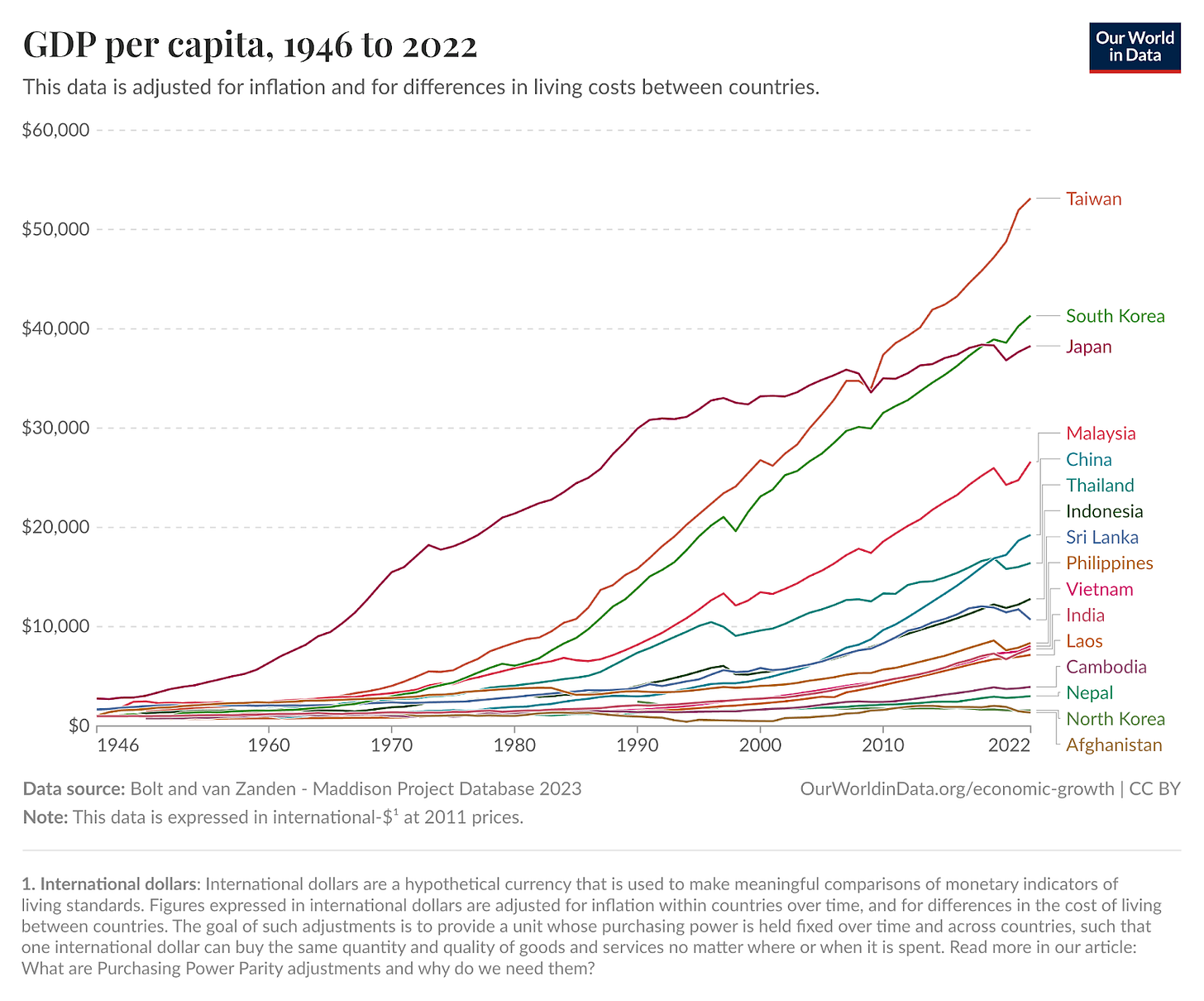

This is the GDP per capita of most East and South Asian countries.

There’s a clear group of outliers: Japan, South Korea, and Taiwan. The rest of the countries are half as rich or less, with Malaysia in between. Why? Japan was already richer, but after WW2, South Korea for example was poorer than the Philippines, Sri Lanka, or even the Congo! What happened?

In How Asia Works, Joe Studwell gives a thorough explanation. It’s because the rich ones did certain things right at the right time. Malaysia did them only half right—hence why it’s poorer. China is following in the same footsteps as JP TW SK, and that’s why it’s getting richer. And if other countries follow the recipe, they will become just as rich. Today, we’re going to explore the recipe, why timing matters, and what this tells us about the world today and Asia in particular.

So what’s the recipe? These successful countries did the right thing, in the right order:

Land reform

Technological learning through manufacturing

Financial support

Three Steps to a Rich Country

1. Land Reform

What’s the best size for farms: big or small? It depends on two factors and one key insight.

The key insight is that the more you work on a farm, the more food you produce per unit of land.

It becomes intuitive when you compare these two images:

The small plot on the left is very intensely worked, and produces an incredible amount of food. Every plant is tended carefully, watered with love, protected from the environment. Every pest is controlled, every weed removed. Spacing between plants is perfect. They are laid in different layers. This plot produces lots of food. Meanwhile, the farm on the right is not as productive per unit of land. But since it’s so big, it produces enough food that overall it can make the farmer rich.

To put numbers on this, Studwell calculated that an intensively-worked garden in the US might produce $16.50 per m2 per year. A commercial farm would produce $0.25/m2.y, so 66x less!

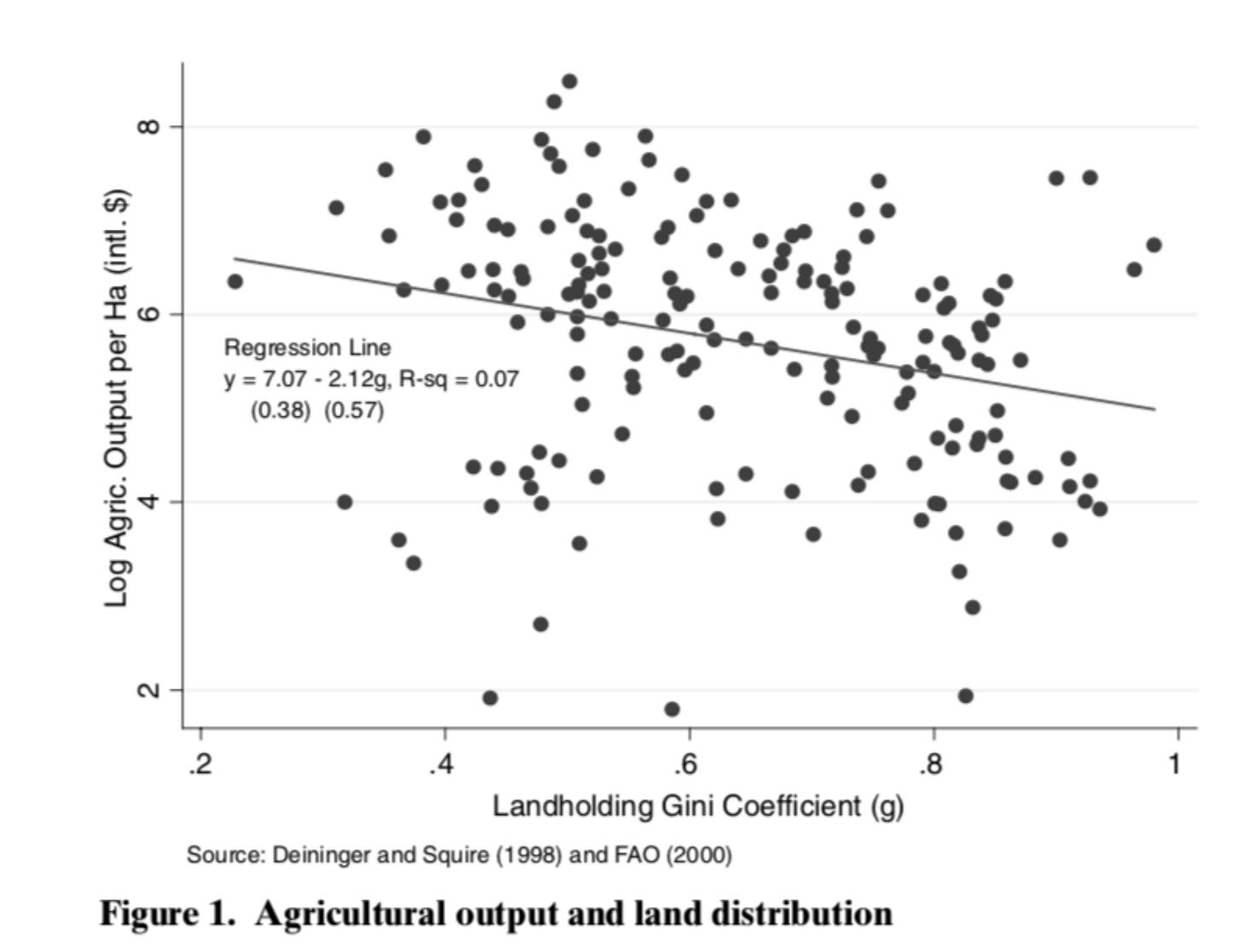

Here’s a graph showing this type of relationship:

So when your land is scarce, you have plenty of people to work it, and you have little money to invest in tractors and the like, you should move towards the type of farm shown on the left. If you are rich, have plenty of land, and are short on potential farmers, you should lean towards the big industrial farm.

In the 20th century, East Asia was poor and very populated, which made the land scarce. That put it squarely to the top left of this graph: It needed small plots very intensely worked. The problem is that land was concentrated in very few hands. As Studwell remarks, in one region of the Philippines, 17 families control 78% of farmland. Overall, the top 10% of owners own 50% of the land. This is a natural evolution of farming, because if one family is very productive and saves lots of grain and another one isn’t and doesn’t, at some point when there’s a bad harvest, the unproductive family will need to sell the land to eat, and the rich one will buy it. Keep doing that over a few generations, and the rich family accumulates more and more money to buy more and more land, and the rest become tenants—hired hands.

The problem is that these hired hands don’t own the fruits of their labor, so they don’t work as hard. The yield of the land goes down. That doesn’t matter too much to the landowner, because he has plenty of land and can buy more. Of course, he forces tenants to work as hard as he can. But beyond a point, it makes more sense to focus on accumulating land than on forcing tenants to work harder.

But the state is not the landowner. Unlike the landowner, it can’t easily expand by buying new land. It has a fixed amount of land, so it wants it to produce as much food as possible to make money.

So what’s the solution? Redistribute land.

By giving the land to the families who work it, you give them incentive to work it hard and produce more food:1 They’re going to keep the literal fruit of their labor!

Of course, the problem is that existing landowners don’t want to give their lands to their tenants, and they have plenty of money, which means plenty of power, and they usually block this land redistribution. So it takes very special circumstances for land redistribution to happen.

These circumstances arose in Japan, South Korea, China, and Taiwan just after WW2.

It was easiest in China: Land redistribution was the biggest proposition of the Communist Party during the civil war that ravaged the country from 1945-49. Later, China made land communal, though, and all the value of this land redistribution was lost.

Taiwan was similar. The Kuomintang, the party that lost the Chinese civil war, had already concluded that it had to redistribute land in Mainland China. When the party escaped to Taiwan and took over power there, it was not very connected with the local landowners—who had been pretty cozy with the Japanese who occupied the land anyways. So the Kuomintang had no ties with the landowners and forcibly redistributed the land.

Japan and South Korea were a bit different. In Japan, they redistributed land in 1868, during the Meiji Restoration, when the Tokugawa government was toppled. Eventually, land concentrated and was again redistributed after WW2, when the US basically told2 the Japanese what to do after their full surrender. In South Korea, the Communist threat (which would lead to the 1950-53 civil war) incentivized the SK government (nudged by the US) to redistribute land: In 1949, it forcibly bought land from landowners and sold it below market to farmers.

Meanwhile, in Thailand, Malaysia, Indonesia, and the Philippines, this redistribution didn’t happen: They tried, but the laws and implementation weren’t as good, and landowners kept their lands. This is the result:

Why does this matter?

In Taiwan, 56% of the population worked in agriculture just after WW2. In Japan, it was about 50%. Perplexity tells me it was 60-70% in South Korea. In other words, more than half of these countries’ populations were agricultural, so it made sense to optimize their output. That was best done by getting the people to work the land intensively. All three countries did that, and this led to huge increases in crop production. Part of their harvests fed each country’s population, but some were sold abroad, which brought currency to the country and funded the state’s next endeavor.

2. Manufacturing with Export Discipline

Once a country is well on its way to producing lots of food and exporting some of it, which brings money back, it’s time to start investing in manufacturing.

Manufacturing is great because you can take low-skilled workers—like the infinite farmers available in these countries after WW2—put them on a machine, and suddenly, they produce a lot more value.

Timing is important: You need to do this after the land reform for three reasons. First, you need lots of workers, who will come from farms. So you need these farms to have been producing for some time, and the families to have grown. Second, you need capital to buy the machines. A few years of crop exports will get you that. Third, as farmers move away from farms and into cities for manufacturing, you need to increase farm productivity, which means buying tractors, seeds, fertilizer, etc. This creates demand for these types of industries.

But if you just spend money on machines, you’re going to burn it: Foreign companies with decades of experience are much better than you at manufacturing stuff, so they will outcompete you: They will produce better products for cheaper. So you need protectionism early on: High tariffs on the industries you want to protect, so they have the internal market from which to grow and learn, which then gives them a chance at building their own expertise. There are other ways to support the domestic industry as well, like cheap loans or direct involvement from the government to thwart foreign competition.

Of course, if you don’t do anything else, the local champions will live cozily behind the import tariffs for foreign industries, extracting rents from their dominant local position. So you need to make sure there’s competition, and then somehow force them to improve continuously, to increase their efficiency and productivity. How do you do that?

With export discipline. The benefits to local champions must be conditional on their exports increasing every year. Why? Because you can’t game exports. If you are exporting more every year, it means you are world-class and getting better. It means at some point you’ll be able to stop supporting these industries and they’ll keep growing as global champions.

Conversely, if domestic companies are not at the cutting edge, you must cull them: Withdraw cheap loans, state support, and even push to sell, merge, or enter bankruptcy.

In this situation, how do you make your industries learn at light speed? How can they get to the cutting edge of technology? You still need to learn from the best. So deals are made between foreign companies and domestic companies (frequently supported by the government) for technology transfer. This can be done in many ways, such as hiring foreign experts, paying consulting fees, offering royalties, limiting sales of foreign companies into your domestic market, conditioning domestic presence with tech transfer, forcing joint-ventures between foreign firms and domestic ones…

Another important aspect is that, for heavy industry, you need the entire value chain to work really well. Back in the mid-20th century, that meant steel and coal, because without them you couldn’t build cheap cars or other manufactures.

Taiwan, South Korea, Japan, and more recently, China, all did these things:

They heavily subsidized local industries

They focused on heavy industries, including coal and steel

They forced internal competition

They culled losing companies

They implemented high tariffs and other ways to limit foreign competition

They conditioned all support on the growth of exports

They did all this some time after land reform

They facilitated technology transfers

This is the result:

All these countries are manufacturing export superpowers.

Meanwhile, none of the other countries in Southeast Asia did this. The one that tried most earnestly was Malaysia, but it failed in many regards. For example, it didn’t push for technology transfers, nor for export discipline. That’s why its exports are fairly mixed between manufacturing and natural resources:

Meanwhile, Indonesia exports an even higher percentage of raw materials:

3. Financing

You’re a lender. You have three options. Which will you choose?

Lend millions to farmers who will buy a tractor and fertilizer and seeds and will hopefully pay you back if the next few harvests are all great.

Lend billions to industrialists with no experience, so they can lose a big chunk of that money for a decade or two until he finally makes his company competitive. Hopefully.

Lend a few hundred thousand to average citizens so they can buy a house, which you can recapture if they can’t repay—in a market where prices will keep climbing because everybody can access mortgage financing.

The greatest incentive for the bank is in lending money to the real estate buyer—or for simple consumption. These loans pay back handsomely with lower risk than the other kinds. Except this is bad for the country overall! The country wants productive land and industries, not expensive real estate. So the state must force banks to lend to industrialists (and farmers, but mainly industrialists, who need it the most).

These loans have to be cheap, so banks must be forced to lend at very low rates—in many countries, negative real rates.

But where will banks get the money? From the farmers who are now richer than they used to be. Of course, if banks are lending to industries at a loss, it means they can’t pay savers much. Savers must lose money when they put it in the bank. Why would they do that then? Because they have no other option.

So countries must have capital controls and prevent things like stock markets or ubiquitous mortgages. The lack of stock markets has the additional benefit that industrialists can’t finance themselves through market stock and bonds—they’re forced to go through banks, which means they depend on the state, which will tell them what to do.

Japan, South Korea, Taiwan, and China all had capital controls early on, no stock markets, negative interest rates for savings, and cheap loans to industrialists. Meanwhile, Indonesia, Malaysia, Thailand, and the Philippines didn’t, and they experienced real estate bubbles and suffered greatly during the East Asian financial crisis in 1997.

Timing

One fascinating aspect of this theory is that it doesn’t work to follow one single policy forever—which is the common belief of organizations like the International Monetary Fund or the World Bank. Instead, countries must have a dynamic approach to their policies.

They must start with land reform to get people working and produce cash.

Then, they should push industrial development with protectionism.

But at some point, they need to liberalize them all. Once farms can invest in capital and professionalize, and industries can compete internationally, the market should decide the winners and losers: Whichever firm is most productive should win. But not before they’re ready!

This is what Japan, Taiwan, and South Korea have developed well:

Redistribute agricultural land to increase yields and get the surplus of population working hard.

Support industry to make people even more productive. Protect it from foreign competition, but push it to prove itself internationally.

Fund this industrialization mainly by capturing citizens’ savings.

As these tricks get you close to first-world levels of wealth, unwind these measures and liberalize the economy.

But can other countries do the same? Here are my thoughts on:

China’s past development and what it will do next

Trump’s tariffs

if Javier Milei can pull Argentina out of stagnation

What the EU should do to develop its Internet industry

Whether Japan can escape its long stagnation

The economic future of Southeast Asia