How Ancient Metals Started Civilization

What was the first metal humans used? You probably won’t guess it.

What did the first metals have in common? It will blow your mind.

What metal promoted the first intercontinental trade?

How did this lead to the first civilizations?

How did its replacement usher in a radically new world?

The stages of human civilization after the Stone Age are the Copper Age, Bronze Age, Iron Age… Why these materials? Why did the Copper Age come first? Why did the Iron Age come later? What came after that? Why did we discover some metals before others? What did each enable? How did the order of metals we discovered influence human history?

These are the questions we’re going to answer today: How metals shaped our early civilization—because they determined the types of tools humans could use, and the civilizations we could build with them.

The Earliest Metals: the Natives of Group 11

Ready for the first metal humans discovered and used? Gold!1

Whaaaat!?

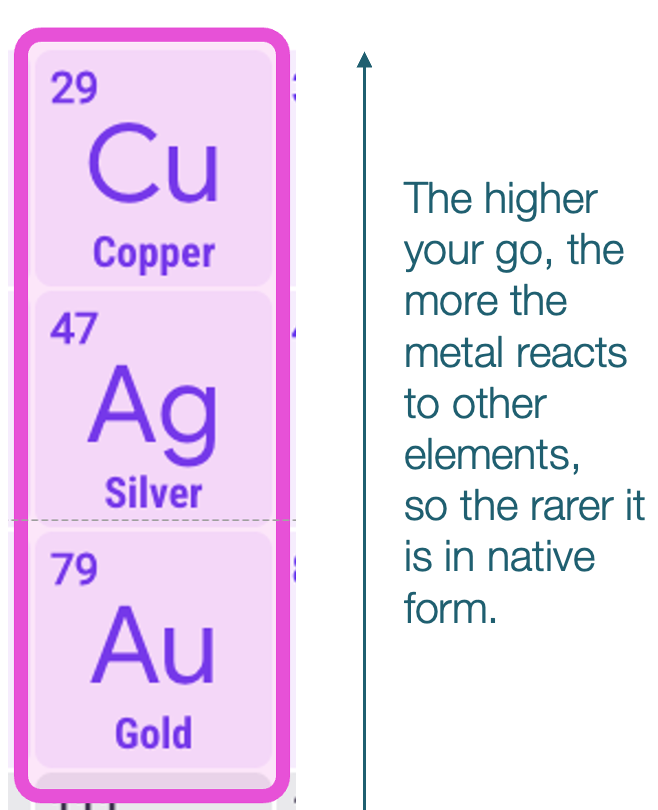

OK here’s another crazy fact: The first three metals that humans discovered were gold, silver, and copper, probably in this order, and here’s how they appear in the Periodic Table.

After your head explodes, you should put it back together and wonder: IS THAT A COINCIDENCE?? I think not. I can hear your brain gears turning: What do they have in common? How did that make them the first metals? How did that determine the history of humans? And then: Oh God, is Tomas going to mix history, geography, physics, geology, and chemistry again? Why yes, yes I am.

But fear not, for I will hold your hand through these scary landscapes and by the end of this article, not only will you better understand the history of humanity, but you’ll also learn some physical and chemical properties of crucial metals for humanity: gold, silver, copper, lead, tin, bronze, iron, and steel.

What the first three have in common—gold, silver, and copper—is that all are native metals: You can find them in their pure form in nature!

Gold

How come primitive tribes carried gold as jewelry and not other metals? Here’s a clue:

Here’s another one:

Yes, ancient humans just stumbled upon gold! What a crazy gift from nature! A metal that is valuable because it’s malleable, doesn’t oxidize, is found in nuggets, with a distinctive shiny yellow color to make it easy to find, and a heavy weight to help separate it from rocks in a pan!

How is that possible? you wonder.

In the Earth’s crust, liquid magma separates materials through different temperatures and pressures. Since gold is so stable, it doesn’t mix well with other materials, and when liquid with a high concentration of gold solidifies, gold veins appear.

Once rocks with gold veins are pushed to the surface, erosion carries the other elements away, which are:

Easier to mix with common elements like water, oxygen, silicon…

Lighter, so easier to carry away.

This leaves behind the gold, which is inert and heavy. This is why people find gold nuggets in small mountain streams: Gold doesn’t travel too far, but it can be carried downstream by violent torrents that erode the materials around it. It tends to accumulate in quiet spots in rivers that follow turbulent sections.

So that’s why we had gold first. What about silver?

Silver

The first difference between gold and silver is that silver tarnishes.

This made it less common than gold early on, because it bonds very easily with sulfur. To form in its pure metallic form, it needs to be in an environment completely devoid of sulfur, or with agents that take the sulfur out and precipitate the silver back into its pure form.2 These are uncommon, but they exist, and form silver in small wires, sheets, and nuggets.

Given its rarity, early on it was just decorative, until we discovered how to get more of it from ore. We’ll see later when that happened.

So gold and silver were, paradoxically given their actual scarcity, some of the earliest metals to be discovered and used by humans. And what did they do with them at the time?

Gold has always been the perfect store of value, because it’s available, yet very scarce, it’s durable (it doesn’t oxidize), malleable (you can shape it easily, so you can easily mint it into coins, and it’s divisible), portable (valuable enough that it contains lots of value per gram, so you can carry lots of value with you), fungible (two pieces are the same), and it looks beautiful, with its shiny yellow color… The other reason why it was so valuable depended on how many hours of work did it take to produce one kg? The more work it took, the more value a metal could store, and gold was still very rare in native form.

However, gold is too heavy and malleable to be a tool or a weapon, so people had no actual use for it except as a store of value… That’s why gold was used as jewelry and for other decorative items: a perfect way to display your wealth.

Silver is similar, but early on it was much less abundant, and less durable because it oxidizes lightly, so it was much less widespread as a decorative element.

Copper

Like gold and silver, copper also exists in native form.

But we said before that native silver was rarer than gold because it binds to other elements more than gold. Well, copper binds to other elements even more than silver.

So we ended up in a situation where, although copper is much more common as an element than silver, and silver more common than gold, their native form is the opposite, so the order of human usage and discovery was the exact opposite!

In other words, gold was the first metal to be known and used precisely because it’s so noble: Since it doesn’t interact with other elements, it accumulated in nuggets that could be easily identified.

Meanwhile, not only is copper rarer than gold or silver in native form, but it’s also much lighter3 and harder than the others, which meant it was more coveted for tools and weapons.

So when we stumbled upon a way to make more copper instead of picking it up from the ground, we paid attention.

The Origins of Smelting

Most metals react too much with other elements to remain in native form. They aren’t pure. They might mix with oxygen and form oxides, sulfur to make sulfides, silicon and oxygen to make silicates…

Some of them are pretty nice, like malachite.

So people used these pretty materials among other things as pigments, some of which they used to decorate their pottery.

They already had kilns, big ovens that could reach high temperatures to turn clay into pottery, tiles, and bricks.

When they added these pigments, they might have seen copper form! Copper melts at 1,085ºC, which is higher than fire pits (400-600ºC), but a temperature some prehistoric kilns could reach. Under these temperatures, the carbon from the wood (for fuel) would bond to the oxygen, hydrogen, and other elements in the ore, and extract them. Liquid copper would be released.

Maybe ore like malachite or azurite found itself in kilns as a pigment, or maybe for some other reason, or maybe it was another type of copper ore. In fact, all of the above probably happened in different places at different times. The result was ground-breaking, though: For the first time, humans could make metal.

And this metal was extremely useful, because it’s hard enough to work as a tool like simple hoes or sickles, it could be shaped into pipes and cauldrons, it can have an edge to become a knife, sword, or arrowhead… So the discovery of copper dramatically improved agriculture, cooking, and violence, which led to a population boom and the ability to wage war.

Copper is also reasonably stable (because it’s in the Group 11 we saw before, along with silver and gold), so it could work as money, enabling more trade, wealth accumulation, and the payment of wages necessary to wage war at scale.

In other words, copper made kingdoms possible. That’s why it’s called the Copper Age.

But before we could move into the next age, we needed another couple of metals.

The Bronze Age: Group 14

Lead and tin were the next two elements to be discovered.

From Pliny’s writings it appears that the Romans in his time did not realize the distinction between Tin and Lead.—Stannum Tin

Why were these the next metals? How come they were the first non-native metals to be discovered? Because you can make them in a normal fire pit!

Lead

Lead is very common in the Earth’s crust, but it’s not a very stable element. It frequently bonds with sulfur to form galena.

Lead melts at 327°C. A wood fire easily reaches 600–800°C. When galena found itself in a fire pit, it became lead!4

My guess is that humans discovered this thousands of times over their history, much before they discovered how to smelt copper. It might have kick-started the technology of smelting.

But lead is not very useful because it’s heavy and way too soft. It couldn’t work as a tool or as a hand-held weapon.

Instead, we used it to cast figurines and amulets, for cosmetics. Later, for early plumbing.

Lead is the heaviest stable element that exists, and this weight was handy for other uses. One was as a weight or a token, super useful for accounting and hence management. The other was as bullets for slings.

However, galena frequently has another metal in it: silver. As we learned to smelt lead, we learned to extract silver. Soon, the value of silver in galena passed the value of lead. This probably had a couple of consequences:

After we discovered the process of cupellation to separate lead from silver, the latter became more widespread. This allowed it to become a currency, and to facilitate international trade.

Because silver justified the smelting of galena, lead became a dirt cheap byproduct that could be used for anything worth using it for. In fact, more than a byproduct, it was a waste product. Because it was so cheap and malleable, it was used for plumbing and cooking vessels in Ancient Rome (and as an additive in wine!), and led to the theory that lead poisoning was one of the causes of the fall of Rome.5

One of the reasons that definitely contributed to the fall of Rome was the exhaustion of silver mines. Like for Chinese empires.

Back to lead. Given its early use, maybe it was the first metal humans worked with heat, and maybe that gave birth to metallurgy, which eventually led us to copper. We don’t know yet. What we do know is that another metal with some similarities to lead was the ticket to the Bronze Age.

Tin

Tin is a puny thing. Like lead, tin is malleable, reacts readily with other materials, and has an even lower melting point, at 232ºC. But tin is more brittle than lead, and much less common in the crust (generally in the form of cassiterite), so I assume random discoveries of the metal would have been uncommon, and when they happened, not found very useful. Tin did not lead to the emergence of metallurgy.

But in some copper mines, tin can be found in the same place as copper. Both metals would go into kilns at the same time, forming bronze by accident. And bronze is very useful.

Compared to copper:

Bronze is much stronger and harder. It doesn’t bend or deform as easily, enabling better weapons and armor. While copper axes dulled immediately and blades bent instead of cutting, bronze weapons endured in battle, providing an incontestable advantage to those who weaponized it. Tools lasted much longer, increasing food production.

Bronze melts at lower temperatures, 950-1000ºC instead of 1085ºC, and is very fluid, making it very easy to work. Mass standardization by pouring it into molds became possible.

Oxidized bronze is stable and protects the metal underneath. Copper oxide is flaky. That means bronze weapons and tools lasted longer.

Bronze springs back, while copper doesn’t and fatigues early. Bronze is useful for gears and springs, enabling mechanisms, while copper was worthless for that. Hinges, nails, clamps, joinery elements, valves, fittings for boats and wagons… all became possible with bronze.

In agriculture, bronze allowed us to cut trees for farmland, break heavy soils with stronger plows than wooden ones, use tools for much longer, and create irrigation systems.

Militarily, bronze enabled long, sharp swords, spears able to pierce shields, durable armor, standardized weaponry for entire armies, and so professional warrior classes, territorial expansion, centralization of force… The birth of empires.

In urbanism, it enabled large architecture, as bronze tools were able to cut stone and wood in a way that copper couldn’t. Palaces, temples, huge stone monuments, and even big buildings were impossible before the Bronze Age.

Transportation was also much easier, because without tools to work stone, you couldn’t have stone roads. Copper also doesn’t produce durable axles, properly drilled wheel hubs, rim bands for wooden wheels, pins, clamps, and rivets that hold under impact… All key technologies for wheeled carts. So no roads and no wheeled carts without bronze.

And we know how crucial transportation technologies were to the formation of empires.

This is an even better example: Without bronze, you don’t have seafaring ships. Stone and copper tools can’t cut cedar or oak into planks, so the size of ships was limited to the diameter of trees. But bronze tools could, so suddenly ships became much bigger. This is when civilization starts expanding in the Mediterranean. There are no Phoenician, Greek, or Roman civilizations without bronze.

These ships also allowed water transportation, which was the only way to transport heavy goods like wood, copper… or tin.

And tin had to be transported from afar, because it’s quite scarce.

Since bronze became vital for development and survival in war, tin became survival. So trade became survival. The scarcity of tin drove trade.

And with it… cities and kingdoms. OK hear me out, because this is nuts: This paper from 2024 argues that the first civilizations emerged not where farming was most productive, but… Where trade between farms and mines could be controlled!

The scientists looked at where the most fertile land was, for agriculture. They looked at where the mines of copper and tin were. Then, the cheapest paths from one to the other. Finally, which of these paths had the fewest alternatives. The idea was: Farmers need tin and copper for bronze tools (and weapons). They will buy these minerals from the mines, so the paths between them become juicy places to make money. If people on those roads tried to abuse their power by robbing or taxing too much, trade would just move elsewhere… Unless it simply couldn’t. These spots were the most likely to have strong cities and states. And that’s indeed what they found!

So although lead and tin are not great metals per se, their early discovery thanks to their low melting point ushered us into a golden age of civilization, maybe by showing us how to smelt ore, by providing the silver we needed to power our economies, and by allowing bronze, which allowed us to get beautiful architecture, better agriculture, stronger armies, faster transportation, international trade, and the emergence of cities, kingdoms, and empires.

The next and final step in this evolution was propelled by iron.

The Iron Age

During the Bronze Age, very little iron was used because we didn’t know how to make it. So the only iron we had came from meteorites, like in Tutankhamun’s dagger.

Why wasn’t iron used early? Mainly because its melting point is much higher than copper, at 1,538ºC vs 1,084ºC. Copper could be smelted with much earlier kilns.

But between 1,500 and 1,200 BC, the Hittites in Anatolia (modern-day Turkey) started building bigger furnaces that reached higher temperatures. Metallurgists likely discovered it accidentally while smelting copper, using iron-rich rocks to help the copper melt. Eventually, they realized the “waste” material left behind could be forged into a new metal. Soon after, iron spread widely.

But why did it spread? Iron is harder to smelt, you also can’t work iron cold, and it’s actually softer than bronze! What’s the point, then?

A tip comes from when iron became widespread.

You see that transition from Bronze to Iron Age? You know what happened at that time, 1200 BC?

During the Bronze Age Collapse, around 1,200 BC (about when the Trojan War took place), dozens of cities were burnt, destroyed, or abandoned; sea invasions took place, maybe caused by droughts or volcanic winters.

The cause and effect are not clear, but the key to untangle this mystery is that iron is everywhere. Virtually all places on Earth have some iron ore nearby. This has radical consequences:

No need for long-distance tin trades. So if barbarians broke these trade lines, people could fall back on iron.

Conversely, anybody could now build iron weapons, so maybe it’s this wide availability that triggered the invasions of the Bronze Age Collapse.

This combines with another killer feature: With the right amount of carbon and metallurgic treatment, iron can become steel, which is stronger and lighter than iron and bronze and doesn’t oxidize as much!

And it’s actually pretty easy to make steel by accident: The same way that copper was first created copper. Remember how burning wood or charcoal releases carbon, which bonds with several elements? Well, steel is just iron with carbon.

So although iron is harder to smelt and process, and not as useful as bronze, it’s virtually everywhere, and its brother steel is much stronger and stable than bronze.

Remember all the consequences we mentioned before about bronze? Iron and steel turbocharged them:

Deforestation on a Massive Scale: Cheap iron axes allowed humans to clear dense forests into farmland.

Better agriculture: Where bronze tools were a huge expense before, farmers could now buy iron agricultural tools much more cheaply, leading to more food and bigger populations.

Mass-Armies: In the Bronze Age, equipping a soldier was expensive, so armies were small and elite. Iron allowed kings to equip thousands of peasants with shields, helmets, and spears, changing the scale of warfare forever.

Long-distance trade was not centered around tin anymore.

Construction became cheaper and sturdier, with nails, hinges, chains, tire bands for wagons, better tools for mining, for construction, for woodworking…

As the supply of wood shrunk after clearing forests, the demand increased because furnaces required lots of wood, both for high temperatures, and because the charcoal resulting from wood was the key source of carbon to form steel.

Takeaways: The Bends in History

Paradoxically, the first metal humans likely handled was gold, because what makes it so valuable (mainly its stability) also makes it the most widespread native metal in nature. Alas, gold is not that great as a tool.

Those are the same reasons why the other native metals followed, why silver was likely the second, and why copper—although uncommon in native form—became so valuable: It was scarce in native form, but unlike the other metals, it could be used as a tool.

Lead and tin are also not very useful as tools because they are so malleable, but they melt very easily. This might have spurred the innovation in smelting technology that produced much more silver, which in turn enabled currencies, and for economies to flourish.

More importantly, it (or pottery kilns) might have allowed the discovery of the smelting of copper, and with it, bronze. Bronze was a game changer because, unlike other known metals at the time, it was hard enough to make effective tools. This radically transformed civilizations: For the first time, agriculture, construction, and war could use good tools at scale. Populations exploded, urban centers flourished, armies expanded.

But bronze required tin, which was scarce. So international trade became crucial—a trade that was enabled by bronze, without which seafaring was impossible, and roads and carts inefficient. This, in turn, birthed the first kingdoms, which were mainly city-states sitting at the right place to control the trade of tin between mines and agricultural regions.

Iron is harder to extract and work with, but it had two killer features that accelerated the development of civilizations: harder steel for better tools, and widespread availability. As iron and steel spread around the world, civilizations bloomed.

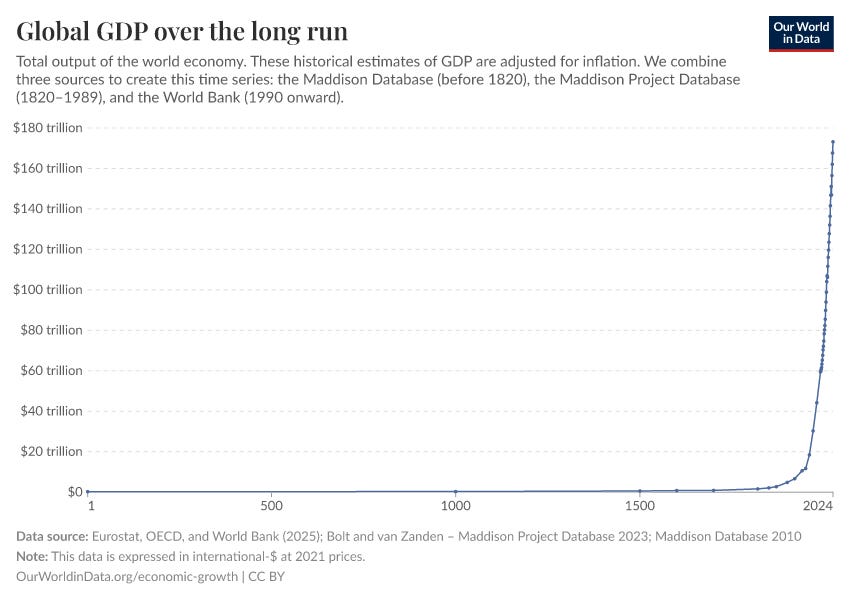

All this made me think of this graph:

What I don’t like about it is that it suggests that humans were poor AF for eons, until 1800 arrived and suddenly we became rich.

But whenever I look at historical developments, it’s obvious that progress is an unrelenting arrow. It’s just that technologies took substantially longer to develop. Sometimes they were forgotten and had to be rediscovered, others they compounded too slowly. But the arrow of development is unmistakable; we’ve been following it for millennia, and now it’s about to take us to the heavens to meet our hand-crafted gods, with tools we’ve built from sand6 and sunlight.

Small amounts of natural gold have been found in Spanish caves used during the late Paleolithic period, c. 40,000 BC. Gold artifacts made their first appearance at the very beginning of the pre-dynastic period in Egypt, at the end of the fifth millennium BC and the start of the fourth, and smelting was developed during the course of the 4th millennium BC; gold artifacts appear in the archeology of Lower Mesopotamia during the early 4th millennium BC.— from Wikipedia

Silver sulfide (Ag₂S) breaks down when sulfur is oxidized, and silver precipitates (becomes metallic Ag⁰) when dissolved Ag⁺ is reduced.

Look at the small number to the top left in the periodic table. It conveys how many protons this element has. Each time you add a proton, you also add some neutrons and electrons, all of which contribute to the weight of the atom. As a result, copper is 17% lighter than silver and 115% lighter than gold.

With heat, it first loses its S atom and takes an O atom. The fuel in the fire would release a C atom, that would then bind with the O in PbO, and Pb remained in pure form.

While Romans did have high levels of lead in them, the lead in the pipes was not the cause of the lead, so not the cause of the fall of the Roman Empire. Water ran constantly in Roman waterworks, and it tended to be alkaline, forming calcite that protected the lead from reacting with water. Lead poisoning happens nowadays because our plumbing stops water, and only in acidic waters.

Silicon!

“Iron” refers both to a fundamental chemical element — the metal that built our infrastructure — and to a vital mineral for biological organisms. In metal form, it enables construction, tools and machinery; in biological form, it underpins oxygen transport, energy metabolism, and many crucial cellular functions. Good old Fe

This was one of your best!!

Very, very interesting. I didn't realise the Bronze Age lasted for roughly 2K years before Iron came on the scene.

Maybe AI will make it cheap enough to be able to feed bronze-age stories into it so that I can watch a documentary about that era, as the movie studios don't seem to go anywhere beyond Troy, I think.