How to Create a Masterpiece

Whether you’re an artist, an entrepreneur, an investor, or any other person trying to create something unique

I’m so frustrated. I talk with many people who want to create—or just try new things—but they remain shackled to their daily lives because they just don’t dare to try. What are their excuses?

”I can’t change careers at this stage!”

”I don’t have time for a side hustle.”

“What if it’s bad? People will judge me. I have a reputation.”

So instead of grabbing them one by one by the collar and shaking them to wake them up, I thought it would make sense to just do it as scale through an article. I’m going to talk to you like I talk to my close friends in an intimate one-on-one. You’ve been warned1.

Spark of Genius

What do the following have in common:

In music, you can find Hooked on a Feeling, Ring My Bell, Funkytown, Tainted Love, It’s Raining Men, Walking on Sunshine, I’m Too Sexy, How Bizarre, Breakfast at Tiffany’s, Bittersweet Symphony, Torn, Turn Me On, Tubthumping…

In movies, Crocodile Dundee’s Paul Hogan, Star Wars’ Mark Hamill, Psycho’s Anthony Perkins, Home Alone’s Macaulay Culkin, Clueless’ Alicia Silverstone, Sex and the City’s Sarah Jessica Parker, Star Trek’s William Shatner, the creators of Blair Witch Project…

In books, The Catcher in the Rye’s Salinger, To Kill a Mockingbird’s Harper Lee, Memoirs of a Geisha’s Arthur Golden, Gone with the Wind’s Mitchell, A Confederacy of Dunces’ JK Toole, À la Recherche du Temps Perdu’s Marcel Proust, Doctor Zhivago’s Boris Pasternak, JK Rowling…

There are uncountable world-class works of art created by people who never produced anything else at that level.

On the opposite side, you have those like Madonna, Shakira, Scorsese, DiCaprio, Pixar, HBO, Hitchcock, Christopher Nolan, Kubrick, Coppola, David Fincher, Iñárritu, Denis Villeneuve, Shakespeare, Stephen King, Mozart, The Beatles, Michael Jackson, Eminem, Taylor Swift, Beyoncé, Meryl Streep… Who just churn out masterpiece after masterpiece.

Outside of art, you can see similar patterns: Most scientific discoveries are made by people who never published anything of that caliber again, like Darwin’s evolution or Mendel’s Genetics. Most successful entrepreneurs only succeed with one company.

But then you have the likes of Musk, Jobs, Einstein, Curie, Newton, Von Neumann, Feynman, Descartes, who might change the world so reliably that they make it look easy.

Why?

Maybe a hint can come from the many creators in the middle: the Wachowskis, Spielberg, Ridley Scott, Fassbinder, Alfonso Cuarón, Godard, The Coen Brothers, who might not consistently deliver. Instead, they produce a bunch of duds, and every now and then something earth-shattering2.

Another hint might come from the trajectories of one-hit wonders. Many try and try and try again for a long time, but just never succeed, sometimes destroying themselves in the process. Others just get comfy with their one hit, get everything they wanted from the performance, and never try again.

Is there a spark of genius that can sometimes catch fire, but not always? Are some people luckier than others, and turn that spark of genius into a blazing fire again and again?

If so, what’s their secret? The audience craves the behind-the-scenes tips from master creators to discover the magic: What process do they follow to tend to that spark?

On rare occasions, creators are self-aware enough that they can describe in lots of detail how they got where they are. Most of the time though, when these superstars unveil their secrets, you realize you have no clue how to reproduce it. That only adds to the mystery: Are some people just gifted with magic dust?

Measuring Genius Sparks

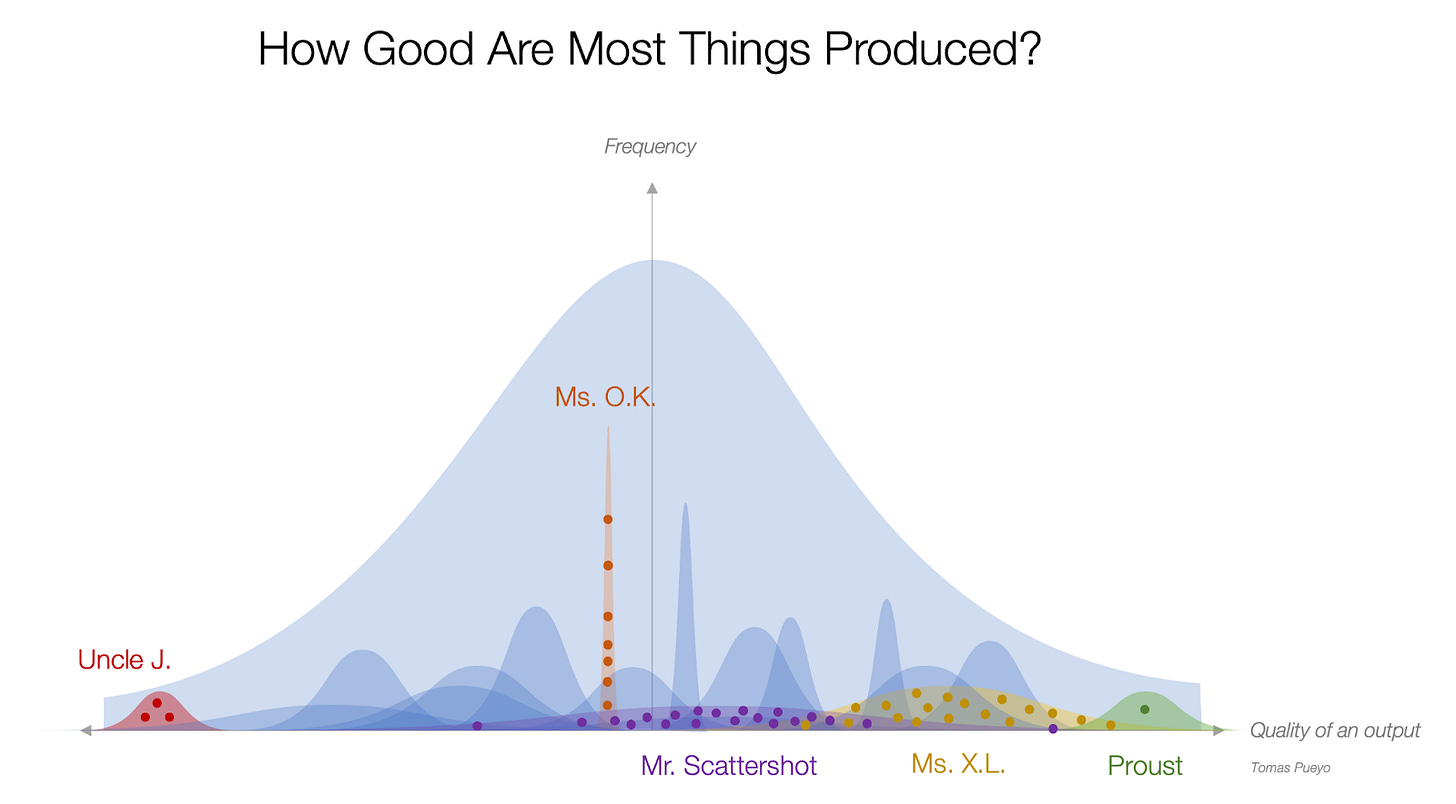

Most stuff people produce is average3. There’s a bunch of crap, a bunch of amazing productions, but most stuff is in the middle. How do you get this shape?

Different people have different types of outputs. But their quality is not consistent. It follows a distribution too. The average of the distributions of every person gives us the overall societal distribution.

Look at Uncle J on the left. No matter what he does, everything will be a failure. Uncle J deserves hopes and prayers.

On the other end you have Shakespeare. Thank god we have some Shakespeares to increase the right tail of outputs. When Newton said he stood on the shoulders of giants, he didn’t mean you and me. He meant the likes of Shakespeare. We all stand on the shoulders of giants, but a few carry other giants on their shoulders. The rest of us cheers along.

When you have Shakespeares, as a society you want to eliminate all barriers to their productivity and get them to produce everything they can.

Most of us are in the middle.

Ms OK is very consistently OK. You know what she will produce won’t be mind-blowing, but she will do it consistently. She’s dependable.

Ms XL is actually quite good. Sometimes she builds things that are good, other times amazing. Every now and then, she is known to produce a masterpiece. But she never really disappoints.

Then you have Mr Scattershot. Scattershot is all over the place. A lot of what he produces is mediocre. Some things are straight bad. But then he's been known to produce some things that have left everybody gasping4.

So what’s the spark of genius?

The truth is that Uncle J is pretty self-aware. After trying three times, he just stopped trying.

Ms OK is very consistent, and that’s valuable. She keeps producing stuff, always at the same level of quality. Ms XL is good and hard-working. Not everything she’s done is a masterpiece; sometimes, she produces some meh stuff. But she does have several gems.

Here are the more interesting ones. Now I changed on the right Shakespeare for Proust, the author of À la Recherche du Temps Perdu. He only produced one thing. After that, he stopped. It was a true masterpiece, but he was a one-hit wonder5. Ever since he published that magnum opus, people have been debating whether he was a genius or just lucky. The truth is he’s a genius—it's very hard to create something truly amazing without this genius—but a bit lazy. Selfish Proust.

And then you have Mr. Scattershot. Most of what he produces is mediocre. But nobody cares. Nobody ever cares about mediocrity. He tried and tried so many times, and he had such a diverse set of skills and tastes, that one of the things he produced was amazing. He was wildly successful. The company Rovio comes to mind here: It took them 53 attempts6 to get to Angry Birds, but once they created that, they never created anything else worth mentioning.

After creating Angry Birds they’ve just been milking it:

They haven’t created any successful new IP since. This is so hard for them emotionally that every year, they cry all the way to the bank to collect their $270 M revenue check.

What does that tell us about creating masterpieces?

How to Create a Masterpiece

To create a masterpiece, the first thing you want is your distribution to be as much to the right as you can. In other words, you should become a genius. You’re welcome.

Thankfully, it’s not the only way.

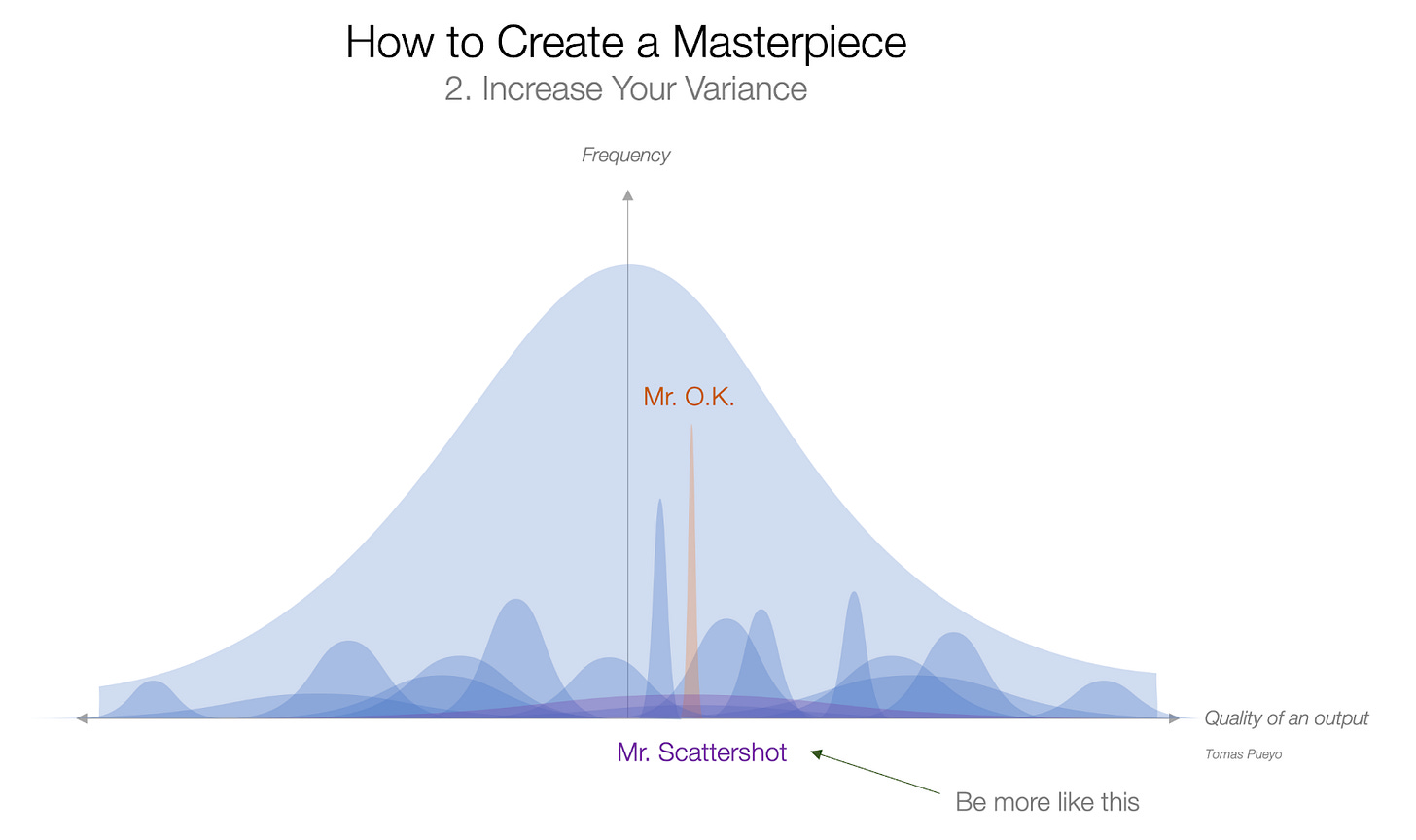

The second way is not to improve your average, but your variance.

Here Mr OK and Mr Scattershot have the same average skill, but Scattershot has a shot at a masterpiece, and OK doesn’t: Mr OK’s bell curve is extremely thin—that’s what “low variance” means—so no matter how many times he tries with this approach, he will only have his attempts fall in the orange area, and they’re going to be mediocre.

Mr Scattershot’s bell curve has the same average as Mr OK’s because both curves are centered at the same level of quality. But Scattershot’s bell is more spread—his variance is higher—so he might land one attempt to the right.

So if both are songwriters and write 50 songs, Mr OK’s songs will all be acceptable, whereas Mr Scattershot will have a lot of songs that should only be played when you need rain, and some others that move you to tears7.

So the second lesson here is to try different things. Don’t invest all your time in one single thing: it becomes too risky. What happens if you spend 10 years honing a novel and it turns out to be a dud? Better to publish early on one novel every 6 months. The first 10 might be terrible, but after that experience, you’re much more likely to have learned, and you will have taken many more shots on goal.

So here’s another way to achieve a masterpiece: quantity.

Here, Ms Perfect has a better average skill than Ms Fukit (the yellow bell’s average is to the right of the green bell’s average), and the same variance (the green and yellow bells have the same shape). And yet Ms Fukit’s track record is better than Ms Perfect’s: Look at the dots to the right. Ms Perfect has one good quality piece, but Ms Fukit has one masterpiece and two more pieces that are better than Ms Perfect’s only attempt. Why? Fukit tried more times, failed more times, and was lucky enough to land more successes.

How to Create a Masterpiece: Quantity

Mathematically, you have three levers to create a masterpiece:

Increase your average: Get better.

Increase your variance: Try different things.

Increase your sample size: Try more times, churn more quantity.

Out of these three, the third lever is by far the best, because it’s the only one that acts on all three levers:

More quantity means you’re going to learn much faster by iterating, and you will improve your average quality. You move your distribution to the right. You improve.

More quantity means you’re going to try several things, different approaches, different disciplines. That will increase your variance.

More quantity means more shots on goal.

Unless you’re lucky, the only way to create a masterpiece is by churning stuff out.

Quantity Has a Quality of Its Own—Not Joseph Stalin.

Examples

We were talking about Shakespeare before, but not everything he created was successful. He wrote at least 38 plays and over 150 short and long poems, including 13 comedies, 10 histories, 11 tragedies, 4 romances… The first few are not very well known, and not at the level of the last ones. How much have you heard about, or enjoyed Henry VI, The Comedy of Errors, or Love’s Labour Lost? The more famous ones are all in the last third of his works: Othello, Hamlet, King Lear, Macbeth…

Or Shakira. Billboard gives her 25 hits across 22 years, the last one just a few weeks ago8. But Wikipedia says she’s performed 198 songs, of which she’s a writer or co-writer of the vast majority. And before her first US hit in 2001, she had been singing and writing for ten years9.

Mr Beast was a high school failure, but he loved Youtube. He spent years analyzing everything about it. Ten years later, he has a media empire with hundreds of millions of subscribers, and is worth more than $100M. His best videos gather more than 100 million views.

I can count 323 videos in his main channel, spanning ten years. That’s one video every 11 days. For ten years.

For years, he barely had any views—and the ones he had are most probably from after he became famous. Go look at his early videos. Crap with a few thousand viewers. Does anybody care? Nobody. Quite the opposite, people are impressed of where he started and where he’s got.

Are people all over Shakira, Shakespeare, or Mr Beast to point out how shitty their early works are? When famous singers publish a new album, does the audience fawn over their breakout songs, or disallow them for the rest of the forgettable songs?

The truth is that the most successful creators:

Create a ton. Most of what they do is mediocre or simply bad. But there are many gems in there. People only remember those.

Explore many genres.

Get better over time.

And nobody cares about their failures.

An Recent Example for Myself: Java

A few months ago, when I was writing the Java article, I felt guilty.

Will my readers care about Java? Do they even know it exists?

Is it too much geography stuff?

I’m talking about freakin’ argisols and oxisols. They sound like Transformers names. Who cares about soil fertility. People will read that and click hard on unsubscribe.

I am working hard on three important article drafts in parallel, and yet here I am, at 2am, studying 19th century Dutch colonization records. What’s wrong with me?

Fukit.

I published the article, recycled it into a Twitter thread, and then this happened.

From Twitter Analytics:

That tweet got me past 100k followers on Twitter. What happened?!

This was especially surprising because I hadn’t struck a viral thread since Musk had taken over Twitter.

Since January 2022, I’ve published 1600 tweets. Only five passed one million impressions. Most of them barely got any. That’s a 0.3% success rate10. You can see it's pretty binary: Tweets are either very viral, or not viral at all.

In other words, most of the stuff I write fails to resonate. It doesn’t matter, because I have more shots on goal, I try lots of things, and I learn in the process.

Yes, But!

OK now that I have given you all these good arguments and examples, you know you can do it too. You can start that project you’ve wanted to try but always hesitated. But you still hesitate. We’ve peeled back the layer of rational excuses, and we’re left with your fears. It’s time to grab you by the collar.

I have had a conversation similar to the one below with dozens of brilliant friends who have some side field they’re interested in, but haven't had a breakthrough yet. Every time, the conversation is the same, so let me just get some economies of scale and write it down here for you all:

TOMAS: You’re very good at this thing and seem to enjoy it. You should do it!

ROUGH DIAMOND FRIEND: Yes, but I have a reputation. What if it fails?

T: Nobody gives a shit if you fail. That’s by definition! If you failed it’s because what you wrote was not worthy of people’s attention. They’re not going to point at you and think “Hahaha look at this failure!” They’re just going to move on.

RDF: Yeah but still…

T: You’re too scared?

RDF: Yes! What if they do find it?

T: Use a pseudonym.

RDF: Ah?

T: Write under another name. If I were to go back to pre-COVID, I might write everything under a pseudonym. You can’t be judged by who you are, you can’t be discriminated against—or in favor—, you’re uncancellable, and you can always opt in to reveal who you are.

RDF: That makes sense. So maybe I should start thinking of a brand name and…

T: No. Just do it. Just publish it. Just publish that song, that blog, that website, that YouTube video, that training, that pitch... Just assume the first 100 are going to be throwaway garbage. They’re going to be a piece of shit. Guess what? Noooobody cares. Nobody gives a fuck about your shitty post. You can always add the brand and the logo later. In fact, it’s better, because right now you don’t know what you’re about. You haven’t discovered yourself yet, because you haven’t seen yourself in action. Believe me, I actually did this. Before I started my blog posts, I spent six months thinking about my personal brand. That was not just cringe, it was all garbage. I had to throw it all. You know the truth? The truth is I was scared of writing. I was scared of failure. It felt productive to think of a brand. But I was just procrastinating. If you keep waiting, you will never start.

RDF: OK I have this thing that I’ve been working on, I still need to hone it, I think I will be ready in two years.

T: No. What can you publish within a month? This week? Tonight? The most important thing you have is your inertia. If you lose steam, you’ve lost everything. Just get going.

RDF: But I’m in an industry where everything takes a very long time to be built.

T: Then your #1 goal is to figure out how to get something out the door very fast to test its success. Startups might take 10 years to be successful, but you can fake your product before building it and try it in days instead of years.There is no excuse.

This is one of the reasons why I started my Substack. It forced me to write twice a week. I needed a forcing function to get 100 articles out a year. Look where that got us: Here you are, reading these lines.

Instead of getting that thing out the door.

If you’re like many, some people in your life need to hear this message. If it can help them wake up, send them this article!

There’s among many things lots of swearing. You know what you’re getting into.

You might disagree with my qualification of one or another creator. If that’s the case, feel free to share in the comments! But let’s agree that a few reclassifications don’t change the key point, that there are one-hit wonders, creators with a near 100% success rate, and lots of things in between.

By definition.

For example, if you follow Van Gogh’s career, it was a bit like that. In his case, the scattershot was due to finding the right type of output (ie painting vs. other jobs).

À la Recherche du Temps Perdu is seven books long. It still qualifies as one work, because it’s the same project. It’s like my twitter threads, but shorter. Proust’s entire project was going to be either known or not. Not one single tome was going to stand out. If that whole thing had not been successful, you and I would not know who Marcel Proust is.

Source: My bad memory from when I worked in the videogames industry. Don’t quote me on that. I don’t want somebody publishing an article in 30 years to say: “We tracked back the rumor that Rovio had created 53 games to a 2022 article from writer Tomas Pueyo, and couldn’t get further from that. Since he didn’t quote a source, we can only assume he made it up.”

I’m talking about the ones that move you to tears because they’re good here. He might also produce some songs that move you to tears for other reasons.

And I wrote this piece before the success of her collab with BZRP!

And as a Spanish speaker who knew her before that, I can’t recognize the name of any songs in her first five years. Most of the songs in the first few years after that are ok.

Even if you consider unique threads and tweets (since I write threads with many tweets) the success rate is pretty low: I have published 125 unique threads or tweets, so the success rate there is 4%.

I just want to let you know that I deeply enjoy all your content. Thank you for not procrastinating.

Thomas, the best thing about your content is that when you dig into a subject you go deep. As a fellow lover of random topics in which I can immerse myself, I have a deep appreciation for your ability to turn that process into relatively succinct and digestible output that is truly educational. Thank you!