Internet Will Kill Nation-States

Like Other Information Technologies Have Shaped Political Systems Before

This article covers some insights I shared live on Austrian TV this week when I spoke at the European Forum Alpbach. For some reason, at one of the dinners of the conference, the organizers thought I belonged to the table with Mr President Van der Bellen of Austria, Mrs President Sakellaropoulou from Greece, Nobel Laureate Joseph Stiglitz, and other very illustrious people. I’ll take advantage of the organizers’ glaring mistake by sharing in this week’s premium article the speech, some additional thoughts about today’s topic, and my take on the conversations I had there—on podcast form! Trying something new. Subscribe if you’re interested.

The speech was about the end of nation-states: how information technologies have been the main drivers of political systems in the past, how the current information technologies—internet and blockchain—will end the power of nation-states, and what will replace them.

This week I’ll cover the first part of the speech: how information technologies have been major drivers of the types of political power in history. Next week, I’ll cover the second part: how I believe our current information technologies will shape political powers in the coming decades.

I hope you enjoy it!

We love telling ourselves that our political systems were crafted by great people coming up with novel ideas, wise founding fathers, patriots revolting against the establishment.

There’s a bit of that. But humans believe they have more agency than they actually do. In reality, what we do is more determined by our context, by systems that drive our actions. We are like pawns on a chessboard.

I find it much more interesting to ask: what underlying systems cause our current society? And if the systems change, how will our society change?

We’re in the first decades of such a massive change. Internet and blockchain are upending everything we know. They will eventually kill the most powerful establishment: nation-states. And I’ll prove it to you by talking with Rigobert.

The 15th Century Shock

It’s January 1st, 1500. Rigobert, a European nobleman, has invited you to his second-tier manor to celebrate the new year.

There’s no clocks, so you’re not sure when it’s midnight. But while eating the desserts, you start pondering the critical juncture in history you’re witnessing: “We’re in the middle of the millennium. What a time to be alive! How do you think the political system will evolve in the next 100 years?”

“What do you mean?” he responds, quizzically—and a bit inebriated.

“Well, you know, currently, the main powers are the feudal system and the Catholic Church. How do you think their power will change in the coming decades and centuries?”

“I’m not sure I follow. What’s the feudal system?” he asks.

“The political system we have. You know, knights, barons, counts, dukes, kings…” you respond.

“And the Church has priests, bishops, archbishops, cardinals, all the way to the Pope. Yes.” he answers matter-of-factly.

“So how is that going to change?” you reiterate.

“What do you mean how it’s going to change? Who will be the next knight? I don’t know, that’s always changing. Sometimes it’s one family, sometimes another.”

“No no no, the entire system!” you correct, exasperated. “You know, for example, before there were Romans, no lords or Church! Then they replaced the Romans!”

“Ah!” he exclaims, finally understanding. “Nothing! That’s impossible! We’ve had this system for, what, a thousand years? It’s not going to change. Ever!”

You couldn’t blame him for thinking this way. He’s known the feudal system all his life. So did his parents, his grandparents, his great-grandparents, and every ancestor in the books. The same is true for the Church.

Over the centuries, dozens of movements protested the Church1. Every time, the Catholic Church learned about them, and systematically crushed them2. The result was always the same: the heretics and their writings were burned, and the Church remained almighty.

Then, suddenly, this happened:

The Protestant Reformation splinters the Catholic Church. Why? Why not one of the dozens of protest movements before? What’s the difference between Martin Luther’s successful reformation in the 1500s and Jan Hus’ Hussites in the 1400s?

To understand this abrupt change, we need to understand how information traveled up to the 15th century.

You can see a village of people as an information processing unit. Every person is a node that talks with each other. There’s only a few people in the village, though, so they’re a small processing unit. They only have very few links with the outside world:

Bigger villages have a representative of the secular power, such as a knight or a nobleman. They also have a priest. Both belong to a hierarchy, with whom they communicate. And there’s a bit of communication with other villages every now and then through parties, trade, or the occasional traveler.

But other than that, these are very secluded places, with few news, few new thoughts coming from outside, few people to exchange ideas with.

This follows a fractal structure, with bigger and bigger lords and clergymen in bigger and bigger cities.

In fact, the aristocrats and the clergy have their own fractal hierarchies, with one big difference:

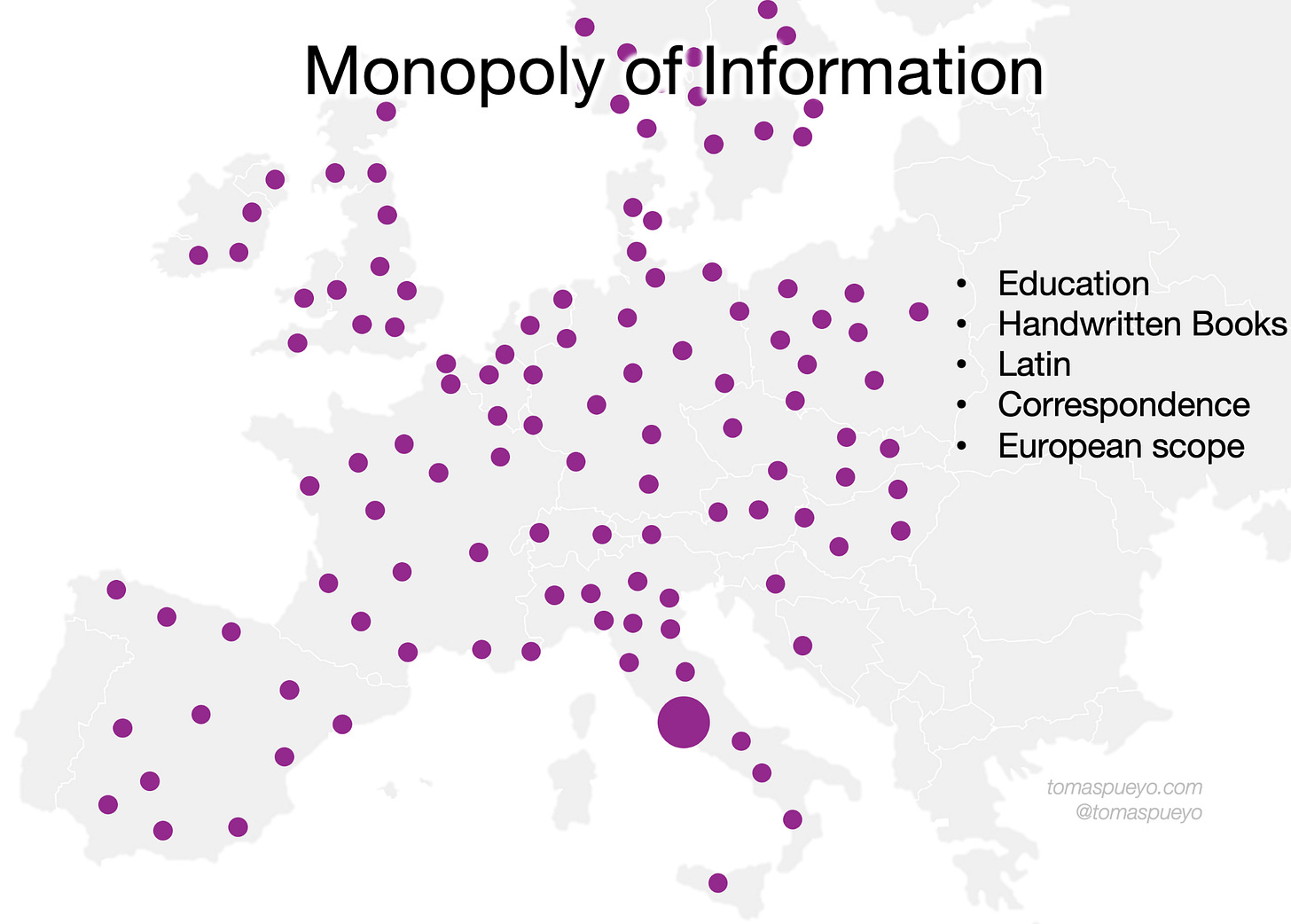

The clergy is substantially better communicated than the aristocrats or the rest of the people. Why?

The clergy was generally educated. They knew, among other things, the local vernacular, latin, and could read. Since the commoners didn’t speak Latin anymore, they couldn’t read the Bible directly, so the clergy became gatekeepers of the relationship with God. The clergy also exclusive had access to handwritten books. They strengthened that with confessions, which gave them access to everybody’s secrets. They corresponded with each other at a European scale. With that, they knew what was happening anywhere and could help each other in a way nobody else could. They had a monopoly on most information and were connected like a vast pan-European network of nodes.

This monopoly of information is at the root of the power of the Church, which was the biggest, uncontested power of Europe for nearly 700 years, between around 800 and 1500.

Then came the printing press.

Thanks to Gutenberg’s printing press, Martin Luther could print his 95 theses.

Thanks to the printing press, Martin Luther could distribute this document broadly and start the Reformation. Within a matter of years, everybody knew about his theses. They had traveled across Europe, with every copy conveying exactly the same message.

Before that, during Jan Hus’ time, the way most people communicated about the problems of the Church was by talking. They gathered at the university, in squares, traveled to see each other. If a priest wanted to have a more lasting impact, he would spend weeks writing down by hand his thoughts, copy after copy. Frequently, people read these books to an audience, to increase the books’ bandwidth. But books took one year to be scripted. So people didn’t write many. Jan Hus was lucky to get a reference in a written book. Probably posthumous though.

With the printing press, all of this changes.

A new network emerges:

From the scope of a village to the scope of a continent.

From a few dozen nodes in each village—which loosely connected to other villages—to hundreds of thousands (or millions) of nodes connecting their ideas to each other.

Each node had access to vastly more information than before: instead of having connections to nodes in their village only, they were connected to nodes everywhere in Europe.

Before the printing press, every manual copy of a book added errors and noise. So older versions were always better. The printing press brought perfect replicability of the ideas, and everybody had the same level of access to these ideas34.

After the printing press, books in fact got better over time: readers would send feedback to editors, which would be incorporated into new editions.

Before the printing press, ideas were forgotten periodically, when those who remembered them died, and until somebody rediscovered these ideas in old books. With the printing press, the ideas were replicated so much that people didn’t forget them anymore. That enabled a catastrophe-proof, continuous build-up of knowledge.

People shifted from being listeners to being readers. Learning no longer required the presence of a mentor; it could be done privately. People talk of celebrated auto-didacts such as Tycho Brahe and Isaac Newton who learned primarily by reading. That would have been nearly impossible before the printing press.

Censorship became a booster of information rather than a hindrance. Before the printing press, censorship was easy. All it required was killing the “heretic” and burning his or her handful of notebooks. But after the printing press, it became nearly impossible to destroy all copies of a dangerous idea. And the more dangerous a book was claimed to be, the more the people wanted to read it. Every time the Church published a list of banned books, the booksellers knew exactly what they should print next5.

All of this caused the Church to lose its grip on power, and alternative sources of power to emerge. The main one was Nation-States, whose emergence was also caused by the printing press6.

As I discussed in Should Everybody Learn English7:

Go back to the 1400s Europe. Latin was the common language in the Church and among some other elites. Outside of that, there wasn’t such a thing as “English”, “French” or “Spanish”. Language was a continuum across the continent, from present-day Belgium to Portugal for Romance languages, or from Scotland to Austria for Germanic ones.

Why? Because most of your communication was with people from your village, your valley. That’s who you shared the most language with. Maybe sometimes you’d talk with people from a village a few miles away. You both had quite a similar dialect, but not quite the same. One valley farther, they spoke yet a bit differently. And so on as distance grew.

That worked as long as in your daily life you mostly talked with those physically around you. The printing press changed that. Now, you had to print a book in a certain dialect, not in a hundred different dialects. So all the people who spoke similar languages converged towards those in which books were published.

Books were published in the cities that had the most writers and potential readers, because that’s where you could get most books and where it was easiest to sell them.

But the writers tended to come from the most populated areas, and publishers wanted to publish books for the most populated areas, so they could sell best. The result was that the vernacular from those areas ended up printed, and that’s what everybody read, which meant more people could read it over time. So, gradually, languages started standardizing around the centers of knowledge—which tended to be the most powerful cities. And this is how you go from a slow gradient to more dramatically differentiated languages.

You can still notice this by the existence of so many dialects and languages in Europe. I’ll go deeper in this topic, as well as the conflict between languages and dialects in Europe, and what they mean for nation-states, in the premium article this week.

Once spheres of distinct languages were created, they tended to exchange many more ideas with the people who shared their language. Whereas earlier on people were either hyperlocal with their vernacular or European in scope with Latin as a lingua franca, now people exchanged ideas primarily with those who shared their emerging regional language. That created a common identity: same language, same ideas, more contact, same feeling of brotherhood. That eventually resulted in a national sentiment: people wanted to be ruled as a unit with those they felt were so similar to them. This was one of the main drivers of the nation-state.

So the printing press at the same time undermined the power of the Church and enabled a new power to emerge, that of nation-states. If our friend Rigobert had realized all of this would happen, after centuries of stagnation, and caused by a small invention, this would have been his face.

And you couldn’t blame him, because he didn’t have access to books, so he didn’t know that this pattern repeats in history.

Yeah, that’s right. The printing press was neither the first time, nor the last time, that an information technology changed politics.

For example, look at these four guys8:

What did they have in common? Why did totalitarianism appear in the 20th century and not in the 19th or the 18th century?

Because of this:

Broadcasting

You can’t talk to a hundred thousand people gathered in a square without a microphone and speakers. You can’t ram your propaganda down people’s throats without a broadcasting system like the radio. And without this reach, you can’t create a personal connection with the millions of people who have to follow you.

Totalitarian states use all the broadcasting technologies they can to brainwash: they take over radios, newspapers9, books publishing, cinemas, education10...

Nation-states were the ones influencing broadcasters’ talking points. These in turn influenced what citizens heard.

This information goes mostly in one direction. Citizens in the 20th century didn’t tell broadcasters what to say. Broadcasters didn’t tell the government what to say. Broadcasting is a one-to-many, unidirectional technology.

Without broadcasting, you don’t have the totalitarian systems of the 20th century. So it’s another technology that enabled a political system.

There are many more examples. I’ll cover two in the premium article: writing and speech. But the short is that:

Speech enabled the first human settlements.

Script enabled kingdoms, churches, and empires.

The printing press enabled nation-states.

Broadcasting enabled totalitarianism.

Big information technologies open the door to new political systems.

If we want to figure out how network technologies like Internet and Blockchain will change the world, we need to understand how the nature of previous technologies determined the emergence of new political systems.

Coordinating with speech is best if many people can hear you at once. That limits the size of your group to a few hundreds of people. You can get immediate feedback though, so you can become close to those you talk with.

But because it’s ephemeral, you must use couriers to send your messages far away. These are unreliable: it’s best if people hear about you directly. So the geographic scope of speech is limited.

All of that means that speech would create small, tightly-knit groups limited to a small geographic area.

Script allowed to convey ideas farther in time and space, which allows for a bigger geographic footprint. It also allows to start accumulating knowledge in a much more reliable way, since knowledge can travel across generations. It allows to put things on paper, which enables trust, without which it’s impossible to cooperate at a big scale. So script allowed for loose groups of people who could connect as far as their transportation system could take them within a reasonable amount of time.

The printing press allows for very quick dissemination of knowledge, so growth can speed up. Initially, it was impossible to control the printing press—the Church tried—, so the spacial units around book printing became nation-states.

As technologies got better, more broadcasting technologies appear, and nation-states took over their control and used these tools to build themselves up. This radicalized their populations, and could even unify nations spread across states (for example, Hitler could annex Austria), but it couldn’t create new nations, or expand the current ones.

Given all of this, what can we guess about the future? How will Internet and Blockchain direct the evolution of political systems?

Crafting the 95 Theses of the 21st Century

Let’s start with Internet:

Internet

The key to internet is that it connects everybody that nation-states don’t split out. Wherever Internet reaches:

Many more nodes connect with many more people. Now you don’t have a few inputs from nation-state broadcasters. You have inputs from millions of people all over the world.

That means much more value will be generated.

There will be an explosion of ideas and of their diversity.

There is so much value in consuming the content that the rest of the world generates, that people will learn English. It will become a lingua franca to ease this exchange of ideas11.

The slower a country is to make its citizens learn English, the slower it will grow.

As English takes hold, a new global identity will emerge, the same way as the printing press formed a national identity.

Bifurcation of worlds, at least in the short term: the same way that broadcasting was harnessed by some countries for totalitarian evil, but in others they became a 4th estate that acted as a check-and-balance against governments, so will some countries decide to use the Internet for a totalitarian direction, while others will embrace its openness.

If totalitarian states can survive, like North Korea, they can remain independent for a long time. The big question here: will China take that path?

But if we trust the arrow of history, the winners are those who create the most wealth. Since totalitarianisms will reduce the value of the network, they are doomed to disappear sooner or later.

Since information disseminates at the speed of light, the scope of our political systems can outgrow the Earth. What about the Solar System?

Emergence of new gatekeepers, like broadcasters, who control some pieces of the network.

What else?

Blockchain

Some of you might be surprised to see Blockchain here at the same level of Internet. I’m still struggling with this concept, but the more I study it, the more it looks like the role of the Blockchain will be as important as that of Internet itself, because the technologies are so complementary.

What Blockchain allows is decentralization. It kills gatekeepers.

You don’t need gatekeepers anymore to get anything done. Governments, banks, insurance companies, universities, schools, music companies, real estate, notaries, energy management… All lose power. Every information industry that has gatekeepers will lose them, because they’re inefficient: they limit the level of information exchange that can exist, and always skim a bit (or a lot) at the top.

In that regard, Blockchain is more similar to other types of information technologies: money and capitalism. We’ll explore them in another article.

The Learnings from the 95 Theses

On the surface, Martin Luther’s theses sound a bit pointless to us: such an obscure disagreement about unimportant theological details! Nothing further from the truth. The parallels between the 95 theses and our situation today are illuminating:

The 95 theses recognize who is the supreme power of the time—the Church—and attack it. Today’s equivalents are nation-states.

They focus on corruption. Whenever somebody becomes a gatekeeper, they invariably take more than they need, just because they can. 500 years ago it was the Church’s corruption; today it’s the corruption of nation-states.

It attacks the blood of the Church: money. That’s also why the Church felt so threatened. The equivalent for today? Taxes.

One of the cornerstones of the theses is how the Church doesn’t have a monopoly on deciding who had repented enough. That was a relationship between people and God. In that regard, the theses were pushing for decentralization. Today, this decentralization is best represented by Blockchain.

The fact that the 95 Theses’ debate is completely pointless to us, but was so important to the people living 500 years ago, tells us that the same thing will happen to us. What matters to us today about the current political system—nation-states, how they relate to each other—won’t matter to people in 500 years. That means patriotism will slowly die.

The theses were presented as a debate, which was facilitated by the printing press. The equivalent today would be Internet debate.

What all of this is telling us is that we’re in a momentous transition. We can barely fathom what will happen. What we do know is that the major force that drove politics for the last 500 years, nation-states, are about to disappear.

The same way that Martin Luther wrote 95 Theses challenging the power of the day, so do we need 95 Theses today to explain the failures of nation-states and how network technologies will replace them with something better.

I’ve laid down a few of these principles, but there are many more. What else should the 95 Theses of Information Networks contain? My next free article will lay out my ideas in much more detail. I’d love to incorporate yours. So please, leave them in the comments!

And if you want to go deeper in today’s topic, subscribe to receive the premium articles. The next premium article will have:

My speech from Austrian TV.

A small podcast with my take on the conversations I had there, with people like Nobel Laureates and presidents of nation-states.

A few in-depth analyses:

How speech and writing influenced the political structures of their times.

Languages and dialects in Europe, and the tension between them.

Some thoughts on why the printing press might have been a key reason why Europe beat China in arriving at the Industrial Revolution.

A moral argument for global English

Why all Romance languages are contiguous in Europe, except for Romanian.

The parallel between the 95 Theses and Russian interference in Western politics.

That we know of, and probably many more that we don’t.

Sometimes without too much effort, other times calling for crusades and creating local inquisitions.

Before the printing press, the word originals referred to the ancient ones, the good ones, the ones with pure ideas. After the printing press, the word took another meaning: originals become those who have novel ideas.

From The Information Age and the Printing Press:

"Scribal culture revered the ancients because they were closer to uncorrupted knowledge—that is, knowledge not yet corrupted through the process of scribal transmission... Print culture, because it allows for cumulative advance of knowledge, views the past from a fixed distance."

This section heavily quotes this amazing paper on the impact of the printing press: The Information Age and the Printing Press.

The printing press also was a key trigger of other megatrends. For example, the Renaissance. With the printing press, finally, humans could build knowledge on top of each other. From The Information Age and the Printing Press:

"Scientific data collection was born with printing" and new contributions became part of a "permanent accumulation no longer subject to the cycle of rapid decay and loss. Copernicus compared the ideas and data of Ptolemy, Aristotle and others; noted their errors and inconsistencies; and published ‘De Revolutionibus Orbium Coelestium’ in 1543—starting the Scientific Revolution.”

The images are new.

Not gals. Worth pondering.

During the early modern period—after 1500—, it was impossible for the Church to control the printing press. But as we get closer to the 20th century, new technologies of control, such as better guns, cars, trains, phones, or electricity allowed for a much easier time controlling it. So the printing press, like all other broadcasting technologies, fell under the power of the nation-state.

As I’ve said before, you haven’t been taught history. You’ve been taught propaganda. But we can go farther: the education system is best understood as a broadcasting technology to foster the nation-state. I’ll go into that in a future article about the future of education.

I wrote a full article on this here: Should Everybody Learn English?

All this reminds me of a feeling I put into words four years ago, just before the french presidential election.

I was trying to prevent someone to vote for the far right, and while talking, I realized I felt closer to the German citizens who did a sit-in to say to french people "please don't go that way, please stay in the EU with us", than to my fellow Frenchmen and women who were about to vote for the far right.

I effectively felt closer to people from a country I've never been to, than to my compatriots.

Closer ideologically, culturally, and even emotionally.

Because we share more values and could communicate in English anyway, so our first language is not even a question.

I think that's when I realized I didn't really relate to the idea of nation-states anymore. Being french/german/american today says less about someone than their values and vision of the world.

I worry about how it's gonna evolve though. Nation-states are not gonna go without a fight, and in the end we still need a place to live. Are countries gonna split in smaller entities ? (not sure that'd be a good sign and done peacefully) Are people gonna be allowed to move more and immigration laws will losen up ? (seems unlikely right now considering the rise of the far right in a lot of places)

Curious about your thoughts on this.

The parallel with Luther's 95 thesis is interesting and your endeavor of building 95 new thesis is ambitious! But upon re-reading your article -yes, your articles are dense and packed with information- it seems to me you presuppose the "killing of the Nation State" by Information Networks as a good thing. However, I would argue that although the current system has many flaws, thanks to Nation States we have some redistribution of wealth (of varying degrees depending on the countries), we have infrastructure (hospitals, roads), public school systems, social security nets. Thanks to strong Nation States, we are starting to see legislation seriously taking into account environmental issues. With no Nation Sates, who would "police" the acceptable behaviour? Who would enforce much needed emission/gender quotas? Who would build the roads that connect small towns? Who would pay for scientific research that has not immediate economic return? Are new Information Networks offering a better solution to these problems? Because what we are seeing now, is that the rise of these Information Networks are, on the contrary, offering a worse system for the majority: bitcoin being used mostly for money laundering and narco payments; social networks being used to spread fake news, conspirationalist theories, propaganda; decentralization used to evade tax-paying... by the wealthiest individuals and corporations, destroying the middle class; bitcoin mining (again) being super energy consuming. Do we really WANT to suppress the Nation State to supplant it with a deregulated system where the only interest taken into account is the private interest? Are gatekeepers superfluouse? Bad per se? How do we make sure the change of paradigm works better for the majority? If you manage to articulate in your new 95 thesis a way to incorporate the "general good", it would be the most powerful blueprint.