Should Everybody Learn English?

“The value of a network grows exponentially to its size.”—Reed’s Law

I became American last month.

Thank you.

As a proper new American, I immediately started wondering: “Should everybody just start speaking English already?”

In the Book of Genesis (am I a proper American or what?!), when humans spoke the same language, they decided to build the Tower of Babel and reach the heavens. God didn’t want that, and His response was to divide people by having them speak different languages. Unable to communicate, they couldn’t build the tower, and scattered. As He had wanted. That’s the first reference I know about strength in numbers, when the whole is stronger than its parts.

Better collaboration understates the value of speaking the same language. To really understand the power of one common language, we need to pick up the phone and call Theodore Veil, the former chairman of AT&T.

Network Effects and the Cost of Not Speaking the Same Language

This is what Veil said in AT&T’s 1908 annual report:

He was publicly stating that AT&T was a natural monopoly, and that it would keep growing pretty much no matter what the company did, because the network effects of telephone networks were so strong.

Nowadays, CEOs are a bit more cunning. Just a bit though. This is Mark Zuckerberg in internal emails debating network effects in the acquisition of Instagram:

Less than one hour later:

All of these people are talking about the magic of network effects. As Metcalfe formalized:

Two people can only have one connection. Three people can have three connections between them. Seven people can have 21 connections… The number of unique connections they can have grows proportional to the square of the people.

Language Network Effects

Imagine you belong to a group of 100 people called EN. Imagine the value of being able to speak with the rest of the group generates for you $10 per year. Since you can talk with 99 other people, you generate $990. The same is true for all 100 of you, so the group generates a total of $99,000 per year.

Imagine that another group, called FR, also has 100 people in the same conditions. They make $99,000 per year too. Both groups, together, generate $198,000.

Unfortunately, EN and FR don’t speak the same language, so they don’t talk to each other and barely trade. If each person only generates $1 for every person from the other group, both groups only add about ~$20,0001.

What if, instead, they both spoke the same language?

Now every relationship adds $10 instead of $1, and everybody’s income doubles instead of increasing just 10%.

In a more intuitive way, if two populations speak the same language, they will interact more, trade more, learn more from each other, and both will be better off.

This is backed by science. Researchers found that increasing the linguistic similarity between two languages by 10% increased their trade by 5%. It’s not the only benefit. Speaking a language makes you more likely to work at, migrate to, and invest in countries and companies of that language. If you speak Hungarian, you have nowhere to go or invest besides Hungary2. But if you learn English, the world is your oyster3.

And the network effects are probably even more valuable, because ideas compound. One group might have the wheel, and another might breed horses. But connect the two and you suddenly get carriages, which are much more valuable than both ideas alone.

That’s not to speak about other types of value. For example, learning a 2nd language can increase an individual’s wages between 5% and 20%. The biggest increase measured in that study was for people learning English. Also, global translation and interpretation costs account for $40B.

Speaking the same language doesn’t just add a bit of value to the population. It explodes its opportunities.

This Is a Recent Problem

Up to very recently, the diversity of the world’s languages was not a problem.

Go back to the 1400s Europe. Latin was the common language in the Church and among some other elites. Outside of that, there wasn’t such a thing as “English”, “French” or “Spanish”. Language was a continuum across the continent, from present-day Belgium to Portugal for Romance languages, or from Scotland to Austria for Germanic ones. Why? Because most of your communication was with people from your village, your valley. That’s who you shared the most language with. Maybe sometimes you’d talk with people from a village a few miles away. You both had quite a similar dialect, but not quite the same. One valley farther, they spoke yet a bit differently. And so on as distance grew.

That worked as long as in your daily life you mostly talked with those physically around you. The printing press changed that. Now, you had to print a book in a certain dialect, not in a hundred different dialects. So all the people who spoke similar languages converged towards those in which books were published. That’s how more defined languages started appearing in Europe: there was a new function for them, that of reading and writing a shared language.

As long as you mostly interacted with your compatriots, your mother tongue was all you needed. For centuries, people barely even needed that. Consider that in 1861 Italy, only 2.5% of people spoke what we now call Italian. Today, just about 53% of Italians speak it as their first language at home. Its spread went hand in hand with the formation of the country at the end of the 19th century and accelerated with mass media and education in the 20th century.

That is changing again now. With the internet, now you don’t just need to understand Italian books and RAI TV shows. Internet is a window to the content of the entire world. Be able to only read Italian and you are limited to a few million pages and speak with a few tens of millions of people. But speak a common language and suddenly the people and content you can access are multiplied by 10 or 100. The allure of speaking a common language is unlike anything the world has ever seen. The network effects are just kicking in.

If the benefits of speaking the same language are now overwhelming, the key question becomes: what language should we all speak?

What Language Should We All Speak?

Maybe we should all just agree to learn whatever language is most spoken already?

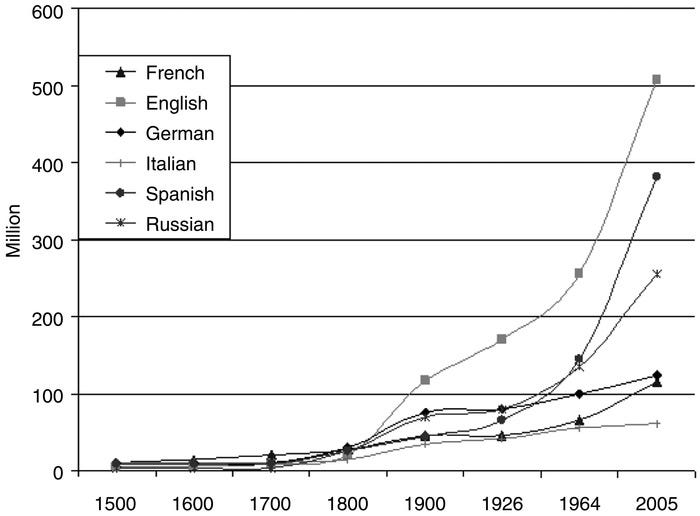

This chart has three issues. First, it shows people, not wealth. You’d rather speak the language of people with money, so you can make more money too.

Second, the graph shows native speakers only. Let’s add all the people who speak the main languages:

Third, the chart doesn’t consider S curves.

Chinese and Hindi only grow at the speed of the Chinese and Indian population.

Meanwhile, native English speakers have been growing faster in number than other European languages.

These are just native speakers. It looks like English (as a 1st or 2nd language) is the fastest-growing major language in the world4.

This graph’s underlying data shows linear growth. I couldn’t find a better source though. So take it with a grain of salt.

Unsurprising, because most of those learning a language are learning English.

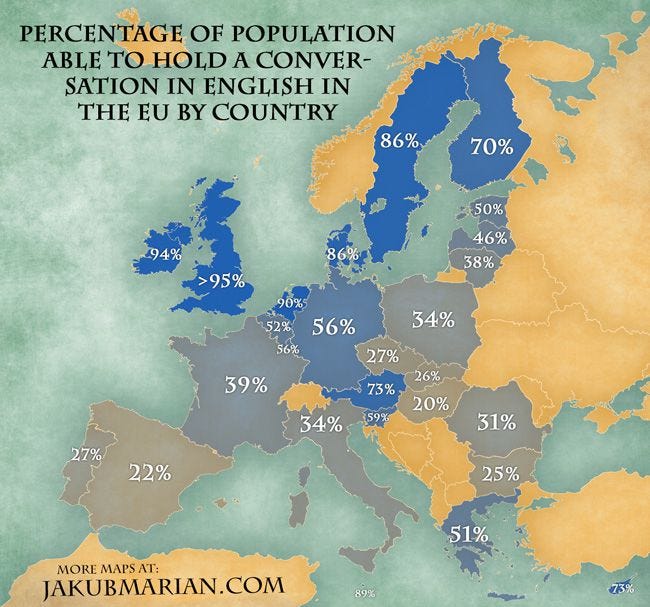

That’s why English is reasonably well-spoken in so many countries.

And think that those who learn English tend to be those who need to connect with other people internationally, which means they tend to be wealthier and more productive, furthering the predominance of English.

It helps that English is also the language that is official in most countries, by far. This matters, because the more countries you have to influence to change official languages, the harder it becomes.

Since English became the lingua franca of the world just as the Internet exploded, an overwhelming amount of Internet content is in English.

"There is virtually no descriptive parameter or indicator for the international or global rank of a language which, if applied to today's languages worldwide, does not place English at the top"—Ulrich Ammon, German sociolinguist, hypercentral language

This trend is self-reinforcing. It only gets stronger over time. Think, for example, about science, where 95% of papers are written in English. If you want to participate, you have to speak it. If you don’t speak it, you must learn it. All the time you spend learning it, you don’t spend it on the science. But the English scientists don’t have to learn it, so they can spend that time on the science, giving them a further advantage, which translates into more English-speaking science, and making English that much more prominent.

All these sources of English’s dominance are probably why, if you ask Europeans, 70% think they should be able to speak a common language, and 67% think English is the most useful one (the second one is French at 25%).

It probably helps that so many already speak it.

Speaking English is an S curve, and its invisible asymptote is all mankind.

How Dare You, Turncoat Tomas? Language Diversity! It’s Important!

Yes. Keep your language. Just learn English on top of it.

And realize that it’s a matter of time before everybody does.

English is not just the language of Anglo-Saxons anymore, just as Latin was not exclusive to Rome after its fall. They both transcended politics to become everybody’s languages. Let’s not allow nationalist chest-thumping cloud the vision of an unavoidable future.

But There’s Been Other Linguae Francae and They Disappeared!

Latin, Phoenician, French, Spanish… Many languages have been lingua franca at some point, and then weren’t. Why wouldn’t it be different with English?

English is special because, unlike other linguae francae (latin insidiously popping back its head in here), it got its status at the very moment we all became connected to each other through the British and then American hegemonies of 19th and 20th centuries.

If another empire suddenly emerged to overpower English quickly, maybe this could be reversed. The only candidate is China, and it won’t grow enough. So we will all learn English. When America loses its predominance, we will all keep using English the same way that Latin was the lingua franca of Europe for 1000 years after the fall of the Roman Empire.

What’s a scenario where English doesn’t become that lingua franca? If suddenly humans discovered the galactic community and we learned everybody in the Milky Way speaks Klingon. Then there’s no way we could impose English as the galactic language, so we would all have to learn Klingon. That’s the only way I see the inevitability of English as the lingua franca of the world.

Unless...

How to Break the Network Effects: Interoperability

The whole argument so far is that network effects are hitting English, and that makes it the inevitable language.

But Network Effects can break. AT&T did have a monopoly on phones until it didn’t, because it was forced to break up, and because of interoperability.

We won’t break up English (what would that mean?). But we could make it interoperable. What happened with phones is that a company could initially prevent other companies from reaching its customers. That’s where the network effects hit: If a company has 50% of customers, and the only way to talk with them is to also be a customer, you will sign up for phone service with that company, even if it’s more expensive.

Interoperability meant you had to allow phone calls between users of different phone companies. The moment that was possible, the network effect vanished, and you just signed up for the cheapest, most reliable phone company.

This is, in fact, how you break network effects: make the nodes interoperable. What would it mean to make English interoperable? We would need a device that translates perfectly and immediately between two people speaking any two languages, no matter the languages.

You already have a very good device like that at your fingertips. If you’re using Google Chrome, right-click on this page and click “Translate to...”. It uses Google Translate, which is a very good instant translation service. It’s not like being a native speaker of other languages, but it allowed me to efficiently read about other countries’ COVID lessons throughout last year. With such tools, I don’t need others to write in English.

You don’t need everybody to write everything in English online, but also offline.

And that’s not limited to writing. You might soon not need English simply to speak with others.

If we can all speak any language and understand any other person, regardless of what they speak, the cost of learning English might be too high for too little reward. People might stop learning it. We might simply use these interoperability devices.

How far are we from technology being good enough to achieve all of this? For the basics, it’s nearly there. Translation and interpretation software might miss nuances, intonation, and similar details, so still some communication is lost. At least in the short term. But technology will keep getting better.

At this point, the question of whether we all end up speaking English or not is a race between the speed of humans learning English and the speed of interoperability technology becoming good enough.

How Can We Use This Information?

For everybody:

If you don’t speak English yet, start learning it (I know some of you use Chrome’s translation tools to read these articles).

If you or somebody you care about have kids, make sure they learn English since they’re very small. If they don’t have proper exposure through formal training or conversation, simply put English shows on TV5.

You can bet on technology becoming good enough soon for instant translation and interpretation to be widespread. Be on the lookout for these technologies, and start using them.

Don’t be afraid of foreign language sites. Use Chrome’s instant translation (or any equivalent).

You can bet on the world sharing more and more of the same culture because we all communicate more seamlessly.

For English speakers:

Don’t be anal about foreigners speaking proper English. See it as a privilege that they are learning your language. Remember, they’re making all the efforts, and you’re there pontificating while reaping all the benefits.

Be especially lenient with exceptions. They’re the hardest to learn and they are in fact a waste. They prevent people from learning English faster. Somebody wants to say she leaded a team? You go girl!

If your kids already know English, the best candidates to learn another language are Mandarin (for obvious reasons), French (because that’s the other fast-growing language thanks to the growing African population), and Spanish (although it isn’t growing as much, LatAm is a core target for American companies).

For professionals:

If you’re a translator or interpreter, learn another trade.

If you work in a tech company, embed these instant translation tools so that people can interact with each other across boundaries.

For example, if you work in a search engine like Google, figure out a way to show search results from other languages as if they were in the language of the query.

For politicians:

If you work in education or relevant governments, push for English to be taught. This is especially true for places like the European Union or India, where English is already there, and the benefits from spreading it further are huge.

If you’re an American politician, you should finance English-learning abroad. The business case is trivially easy to make, and it will reinforce America’s power as a country that doesn’t need to learn English and that masters the language that everybody speaks.

If you work at the European Union, stop wasting billions of euros in language-to-language translation, acknowledge English has won, and act accordingly. It doesn’t matter that the UK left. It’s not their presence that made English the lingua franca. It’s two centuries of English hegemony during the entire globalization era. Stop feeling like your home language is threatened. It’s not. Europeans can learn more than one language. Of course, still allow any citizen to address the European Union in their language, but between politicians and bureaucrats you should just speak English.

If you want to break network effect monopolies (eg, Facebook), don’t break them down. Just make them interoperable. Instagram grew originally on top of Twitter. Zynga grew on top of Facebook. Force these big companies to allow smaller companies to use the social graph, and their monopoly power will disappear instantly.

For investors:

If / when such a law passes, you might consider immediately selling your stock in the biggest companies that are compelled to become interoperable6.

Meanwhile, you can bet on the market for learning English to keep growing.

What other takeaways can we draw? Leave your ideas in the comments!

Each member of A now gets $99 more every year. Since there are 100 members in EN, that’s $9,900 generated in EN, and the same in FR, for a total additional $19,800.

Sorry Hungarian friends. I had to pick on somebody. I picked you because I like you and I know you won’t be offended.

In reality, the value is higher than that, because the value of the network is not all the individuals you can talk with, but all the groups you can talk in. There are many more possible groups than people. This is Reed’s Law.

I can’t find detailed data on the evolution of the number of speakers of English as a second language, so let me know if you find some.

There’s millions, from Peppa Pig to PJ Mask or Paw Patrol for the young ones—which I’m most acquainted with given my children’s age.

This is not investment advice. This is for informational, educational, and entertainment purposes only.

I usually love your articles, but this one is lacking a leg, so to speak. Yes, English dominates in the technological and commercial spheres globally but languages are more than that. They are intrinsically related to culture, food, music, a way of thinking, a logic, so to speak. These are things that might not have a high economic value (and that is debatable), but have a high emotional value. When companies seek people to work abroad, they are not only looking for people who speak English, but for people who understand and can relate to the cultures they will be working with and that, my friend, usually comes with learning or knowing the local language. I am in the middle of moving from the US to South Africa for work reasons, and I cannot write as extensively as I would like to. I was born and raised in Mexico and became a US citizen around 20 years ago. Congratulations on your American citizenship. I speak four languages and have passive knowledge of a fifth one, and I suspect you do too. I am a translator, and I still have to see the day when apps like Google translate will be able to translate a patent application. What I have seen in the over 20 years that I have been living in the US (intermittently because we frequently relocate abroad for work reasons) is a push to make the world monolingual, in English of course, and that will most probably never happen. I have a 14 year old daughter who was bilingual English-Spanish when she came to the US for the first time when she was 9 years old. She is now starting 9th grade, and the ability to speak and write Spanish has reduced substantially (she can still understand and read because we speak Spanish at home). You will probably face this situation yourself as your kids grow older in the US (unless you are rich enough to keep them in private, truly bilingual schools and out of the public system average schools). Making people monolingual, in English or any other language, at this point in time, works to their disadvantage, both socially and economically. Deep friendship bonds develop by sharing, among other things, a common language and culture. I have experienced this repeatedly over and over during my time abroad. Yes, learn English, but as a second, third, fourth or fight language. Advocating for English as the main language is not realistic, and leaves one half out of the equation: The cultural aspects and benefits different languages brings to those who speak them. I wish I could write in more detail, but I just do not have the time now.

I'd like to supplement this information: IF you're an English speaker and only speak English, start learning another language now. Like, today. Portuguese or Spanish are extremely good options.

And, if English are your second language, start learning a new one, like, today. Portuguese and Spanish and maybe Hindi are good options.

Why? Because culture. Because literature and music and richness of thought. Knowing more languages and being able to speak to more people in them carries infinite rewards.