Is Venezuela’s Oil Worth the Hassle?

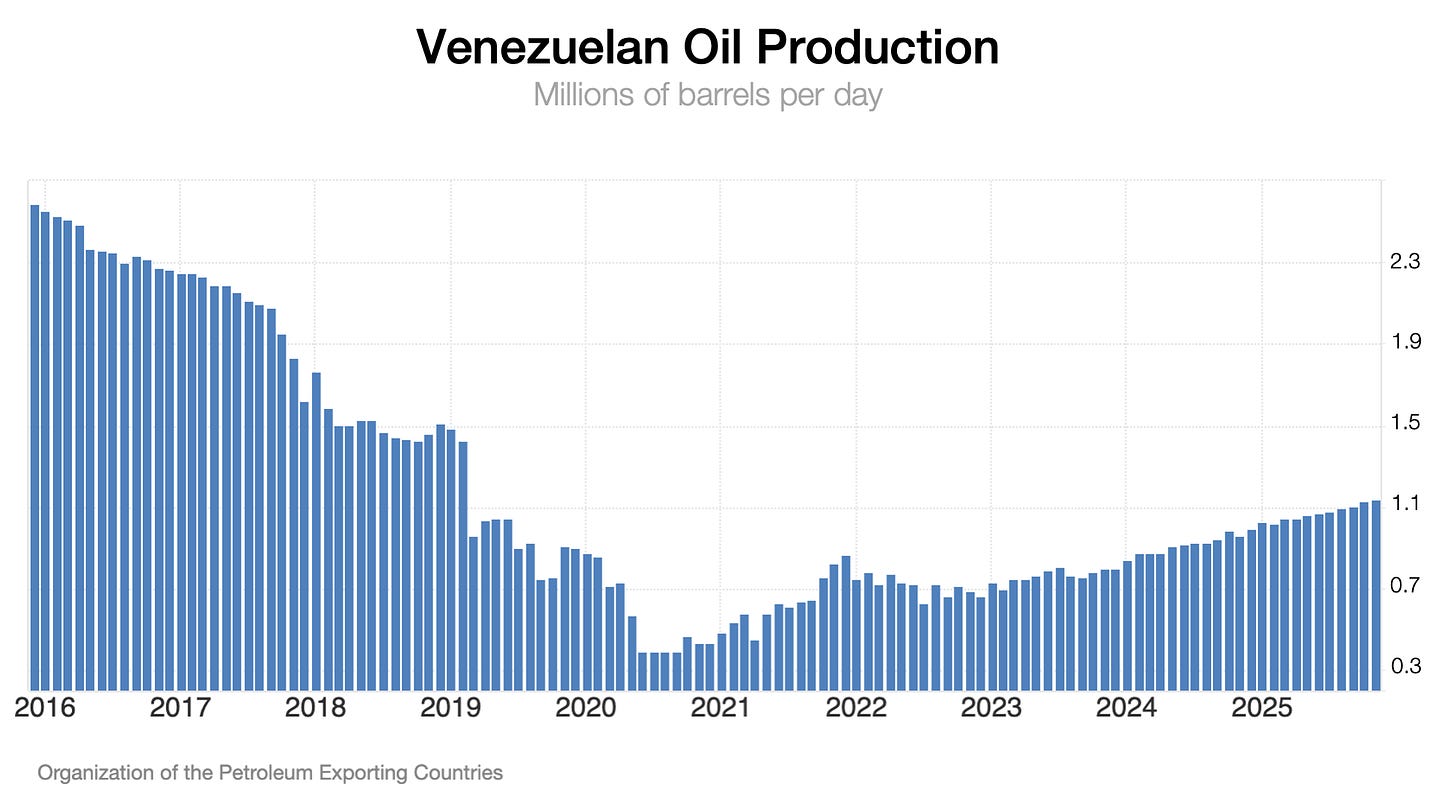

Trump claims that the abduction of Maduro is all about the oil: capturing it for US use, while keeping competitors from its benefits. But how realistic is it? This depends on how much oil can be extracted from Venezuela. Today, it’s ~1.1M barrels per day.

Venezuela’s Oil Today

A barrel of oil is currently worth about $60:

But Venezuela’s oil is worse quality than most, so it sells for cheaper, ~$8 less as of today, or $52.1 Let’s assume that continues.

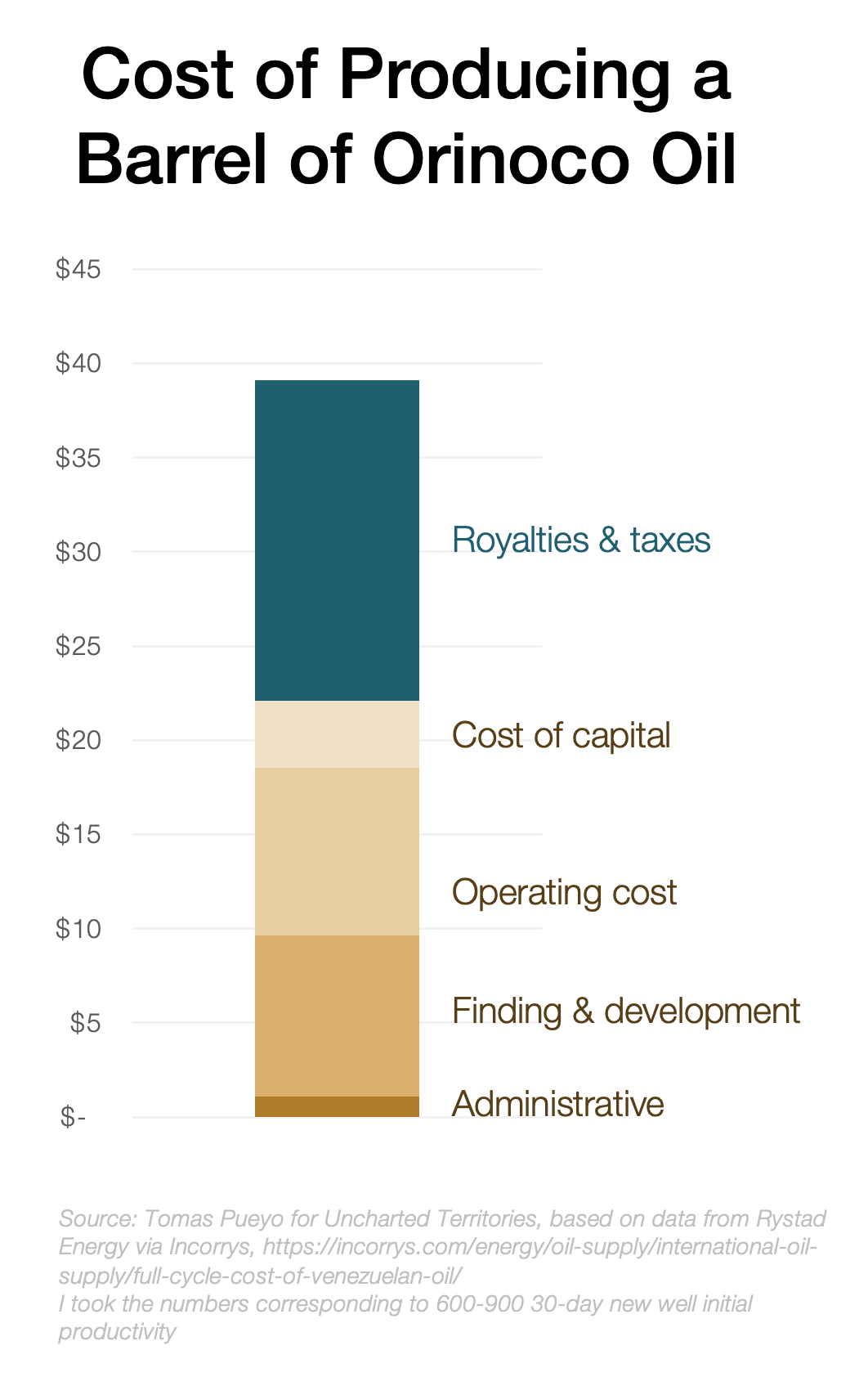

But how much does it cost to extract a barrel of Orinoco oil and transport it and treat it to be sellable?

So of these $52, about $23 are hard costs, and each barrel yields around $29 in profit.

For 1.1M barrels per day, that’s ~$32M per day, or ~$11.7B per year. That’s how much money Venezuela could earn from its oil.

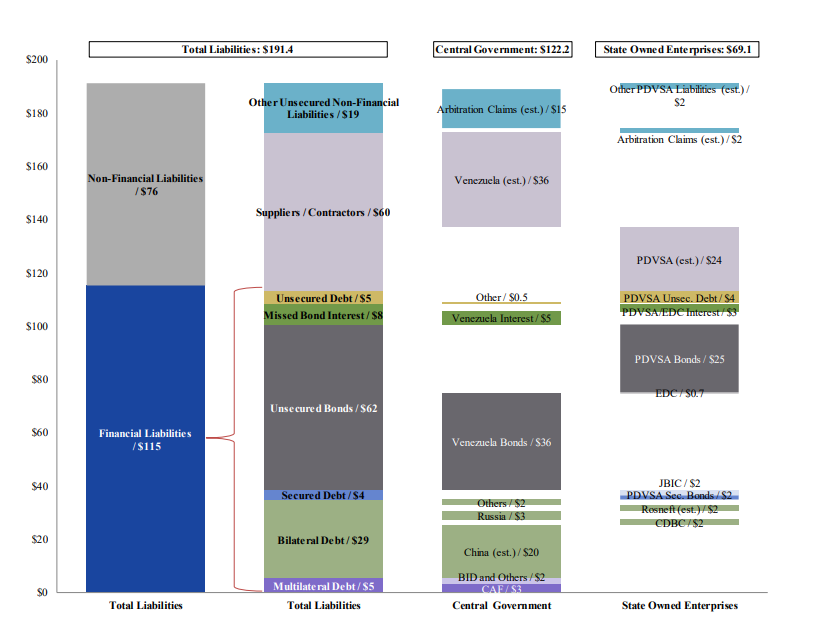

Compare this to the current situation in the country:

The Venezuelan government’s last budget asked for ~$20B, or almost twice the revenue that can be obtained from oil production.2

Venezuela owes ~$200B, or nearly 20 years worth of production!

ConocoPhillips alone is owed $12B, about a year’s worth of all of Venezuela’s oil revenue!

So either the US makes no money from Venezuela, or it plunders the oil and leaves Venezuelans to starve and die—won’t happen—, or it invests to decrease costs and increase production.

Now, decreasing costs is very hard because, as we saw in the previous article, the oil is superheavy. As Nigel Harris said in this comment:

In Saudi Arabia, all you have to do to extract the oil is drill a well, and control the resulting flow of oil and gas, which comes bursting out of the ground under its own geological pressure. Let the oil sit in a tank for a short while, and the gases bubble off (and are captured for use as fuels) and the water and sand settle out. The oil is ready to transport by pipeline and ship, and is of a quality readily handled by almost any fuel refinery in the world.

The oil [in the Orinoco Valley] is extremely dense (heavier than water), extremely viscous (like pitch or molasses) and extremely dirty (over 5% sulfur and masses of metals like vanadium). The only deposit like this elsewhere in the world is Canada’s Athabasca oil sands.

To extract the oil, you have to first pump large amounts of steam into the formation, to melt the hydrocarbons, then use electrical pumps at the surface or in the bottom of the well, up to a kilometer deep, to lift it to the surface. Once there, the “oil” is far too viscous to transport by pipeline or ship, and far too heavy and dirty for most refineries to tackle. So it is diluted by mixing with a much lighter crude oil, or the “condensate” liquids from a gas field, or refined naphtha (a solvent which you can buy as “white spirit” in UK DIY stores). The resulting diluted crude oil (DCO) is exported as Merey blend. This is still one of the heaviest, dirtiest crude oils in the world (16 API, 3.5% sulfur, high acidity and metals content), but it flows just well enough to be transported if kept warm, and some of the world’s more complex refineries can handle it, and make transport fuels from it, although usually alongside other lighter crudes.

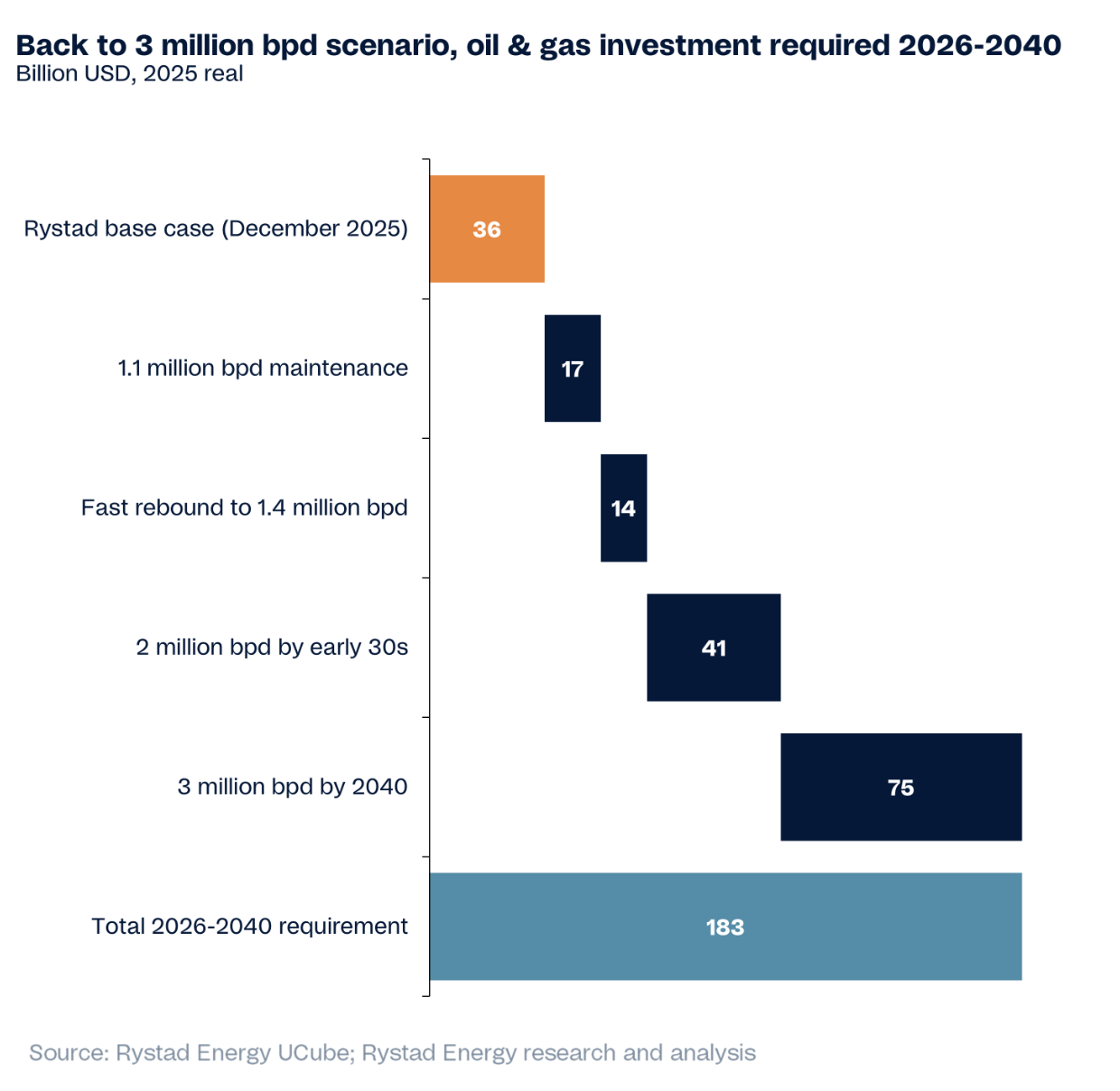

So the only way to increase Venezuela’s oil revenue is by producing more crude. The problem with that is the investment required is massive.

Increasing Venezuela’s Oil Production

The two best estimates suggest it would take tens of billions to maintain the existing infrastructure, and tens of billions more to go beyond that.

Why? Because we would need to build more refining capacity, more export terminals, more tankers, more oil pipelines, more electricity generation to power the steam to dilute the heavy oil… The investments for final refining would certainly happen on US soil, but all the rest would have to happen in Venezuela.

In the graph showing the cost of a barrel of oil, we had sections for Finding & Development and Cost of Capital. That is what would normally cover these costs. But that’s $12 per barrel today, so adding 1M barrels per day would only pay for ~$4B per year. Not enough to cover the tens of billions of upfront investment needed. So the margin that the government keeps after all this investment would shrink.

That’s assuming oil companies want to do this. But why would they? They’ve been stripped of their Venezuelan investments not once, but twice!

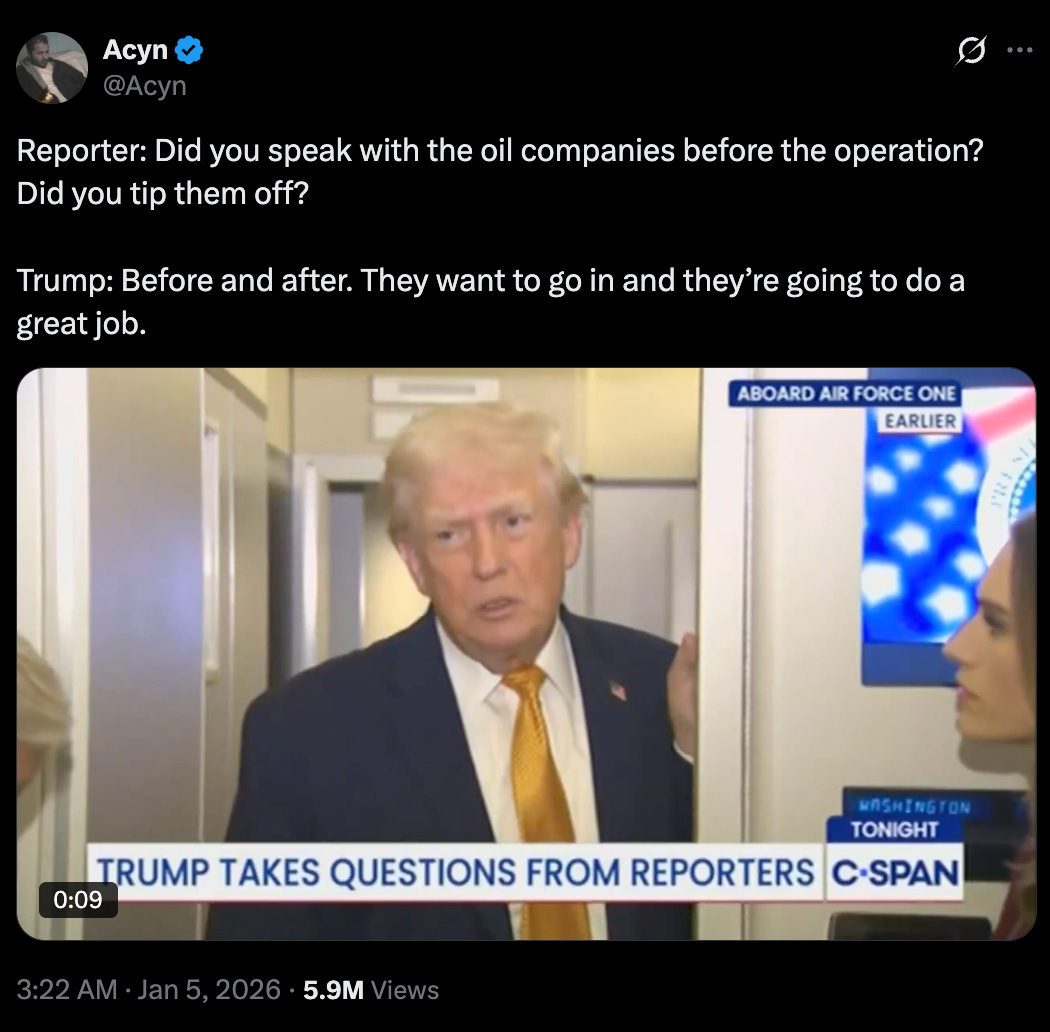

That’s why Trump met with oil executives a few days ago to get commitments to invest $100B into Venezuelan oil, and why the executives answered lukewarmly.

We have had our assets seized there twice and so you can imagine to re-enter a third time would require some pretty significant changes from what we’ve historically seen and what is currently the state. Today, it’s uninvestable.—ExxonMobil CEO Darren Woods.

For these companies to invest that money, they would need assurances that they will be able to pump oil for decades without their investments being nationalized again.3

Which means that this is only going to happen if the US can guarantee the rights of US oil companies in Venezuela for the next few decades…