Venezuela’s Excrement

Why the country is rich only in oil, yet destitute and authoritarian today

Ten or twenty years from now, you will see, oil will bring us ruin.—Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, Venezuelan minister primarily responsible for the creation of OPEC (along with Saudi Arabian minister Abdullah Tariki), 1976

The world is in shock after the US took Venezuela’s leader Maduro, and the takes keep piling up, but they each focus on a tree rather than the forest. Why? What does it all mean? What will happen with Venezuela and the Venezuelans? Was this a legal or legitimate action? How does that affect the US, Russia, and China? How does it rewrite the rules of the world?

At the heart of all these questions is one thing: oil. So today, we’re going to look at Venezuela’s economy, why it’s mostly centered around oil, and why it has caused the situation we’re in. In the next article, we’re going to look at the ramifications.

Venezuela: Yesterday vs Tomorrow

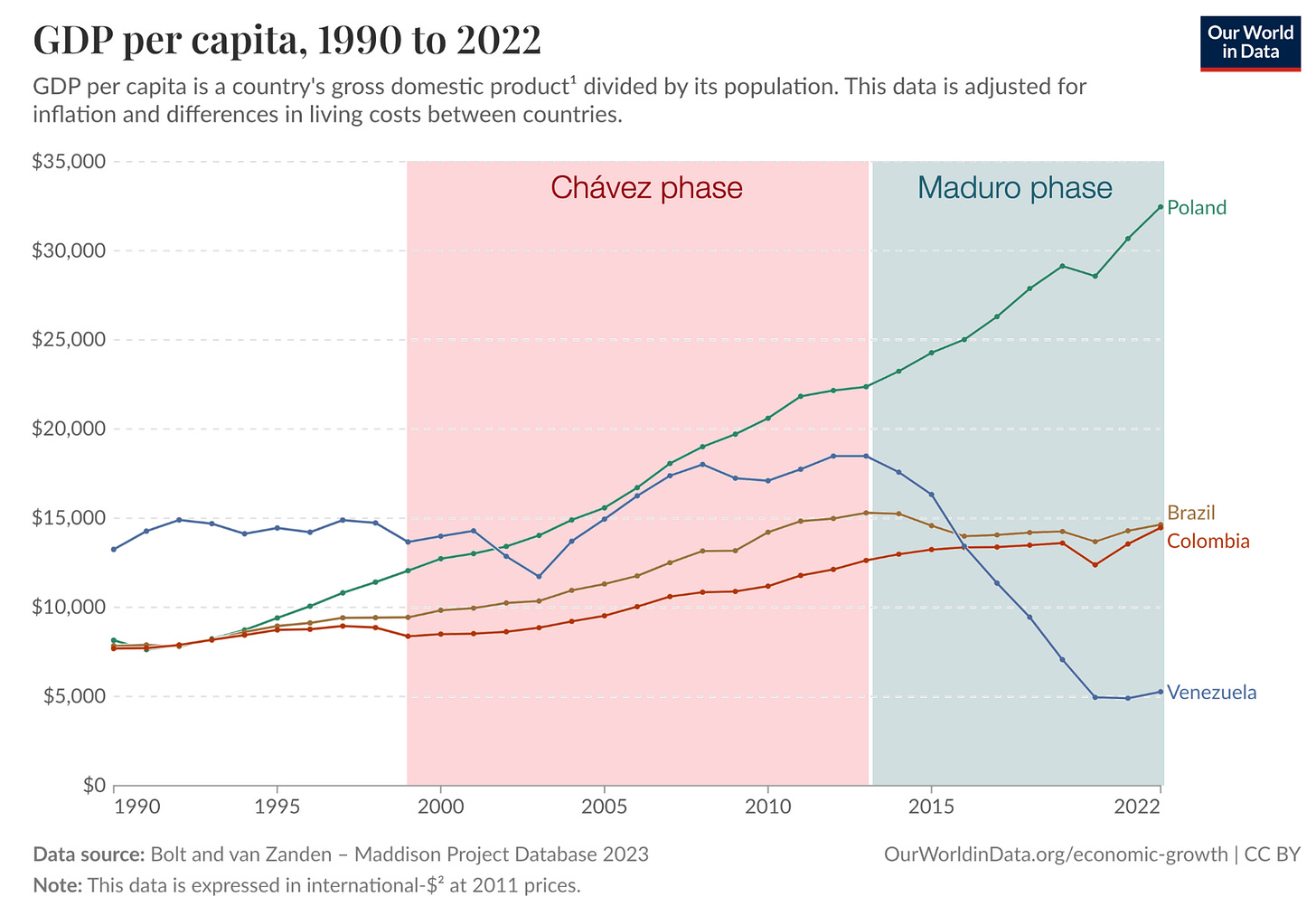

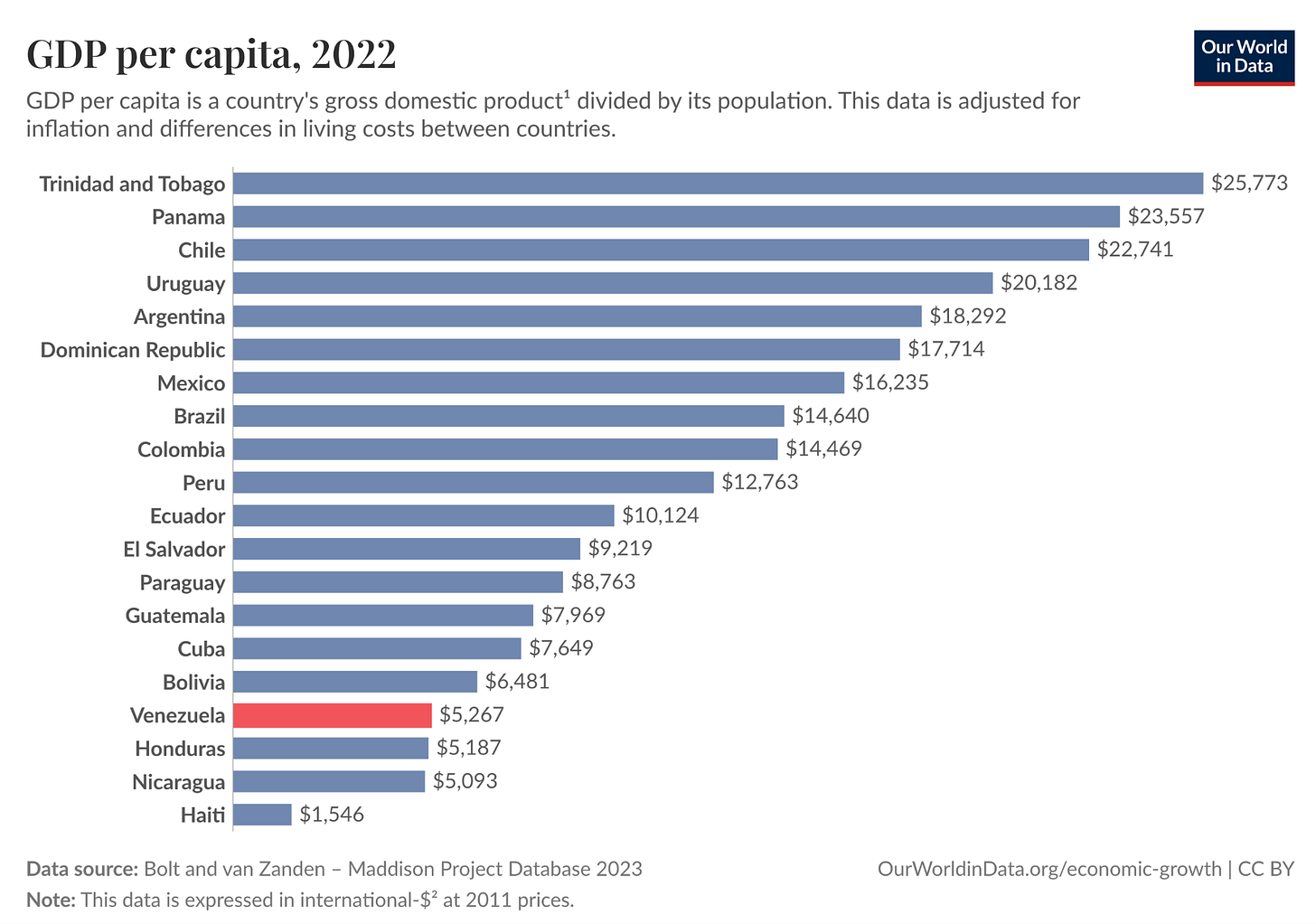

When Chávez took power in 1999, Venezuela was one of the richest countries in Latin America.

Now, it’s among the poorest.

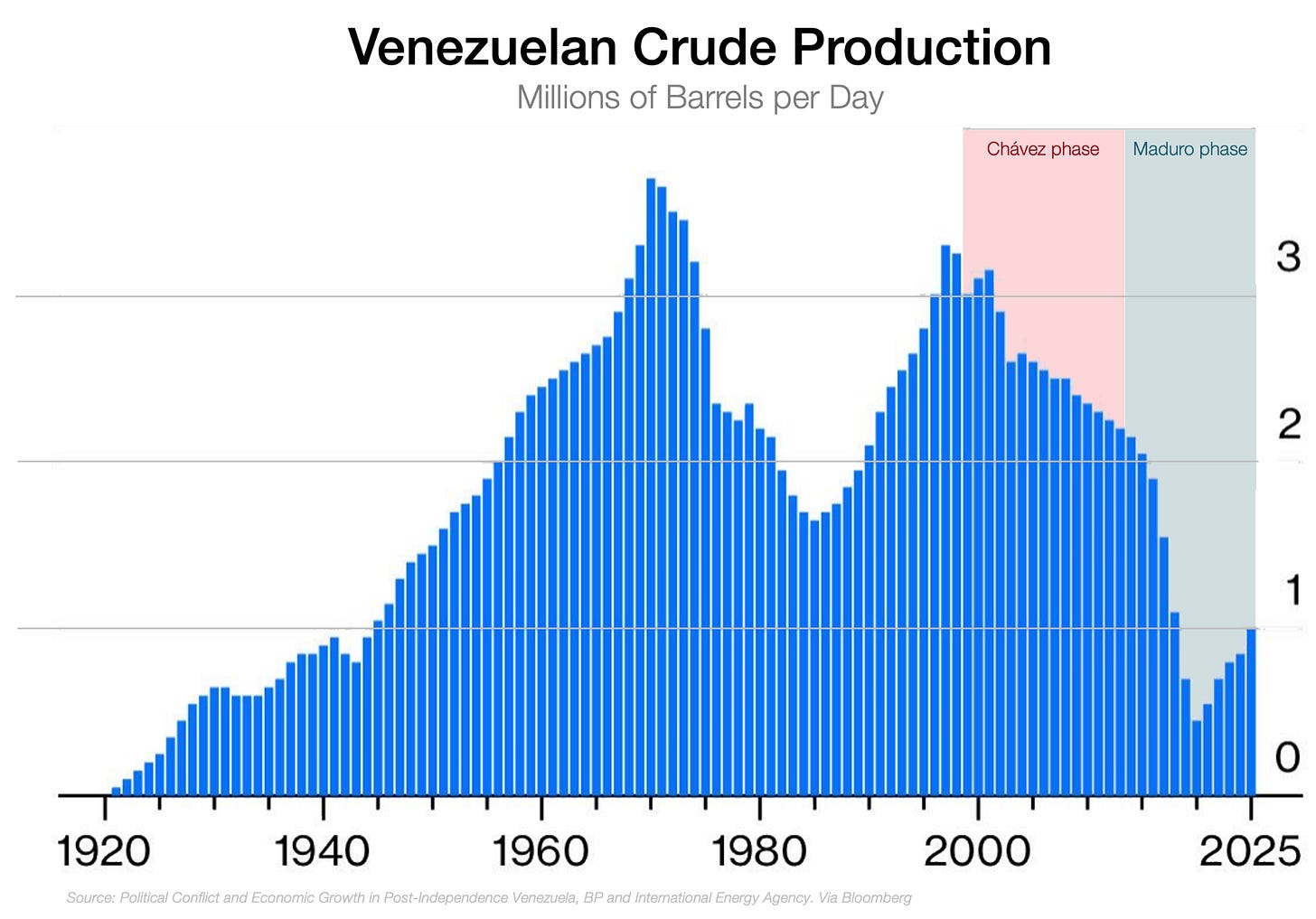

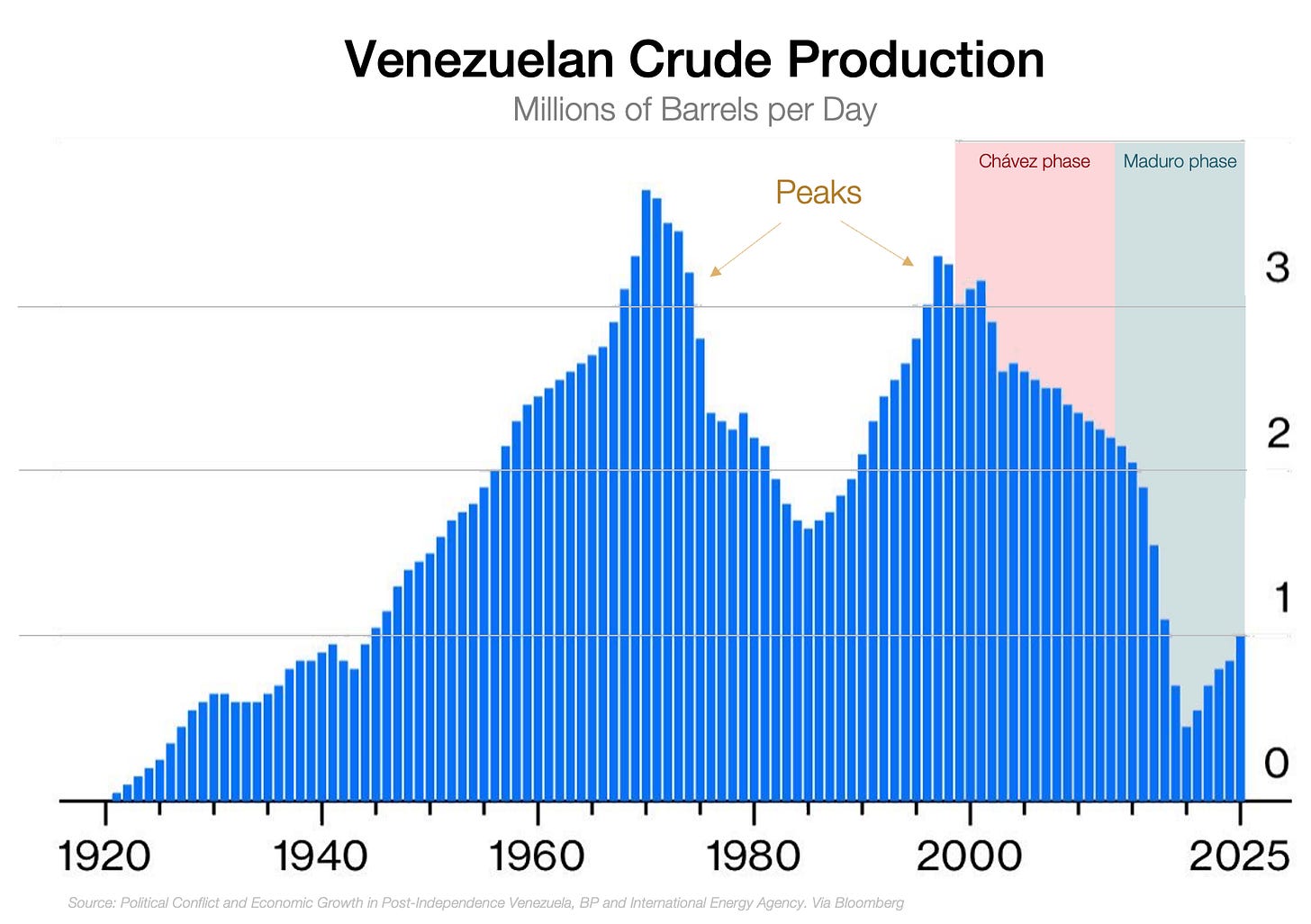

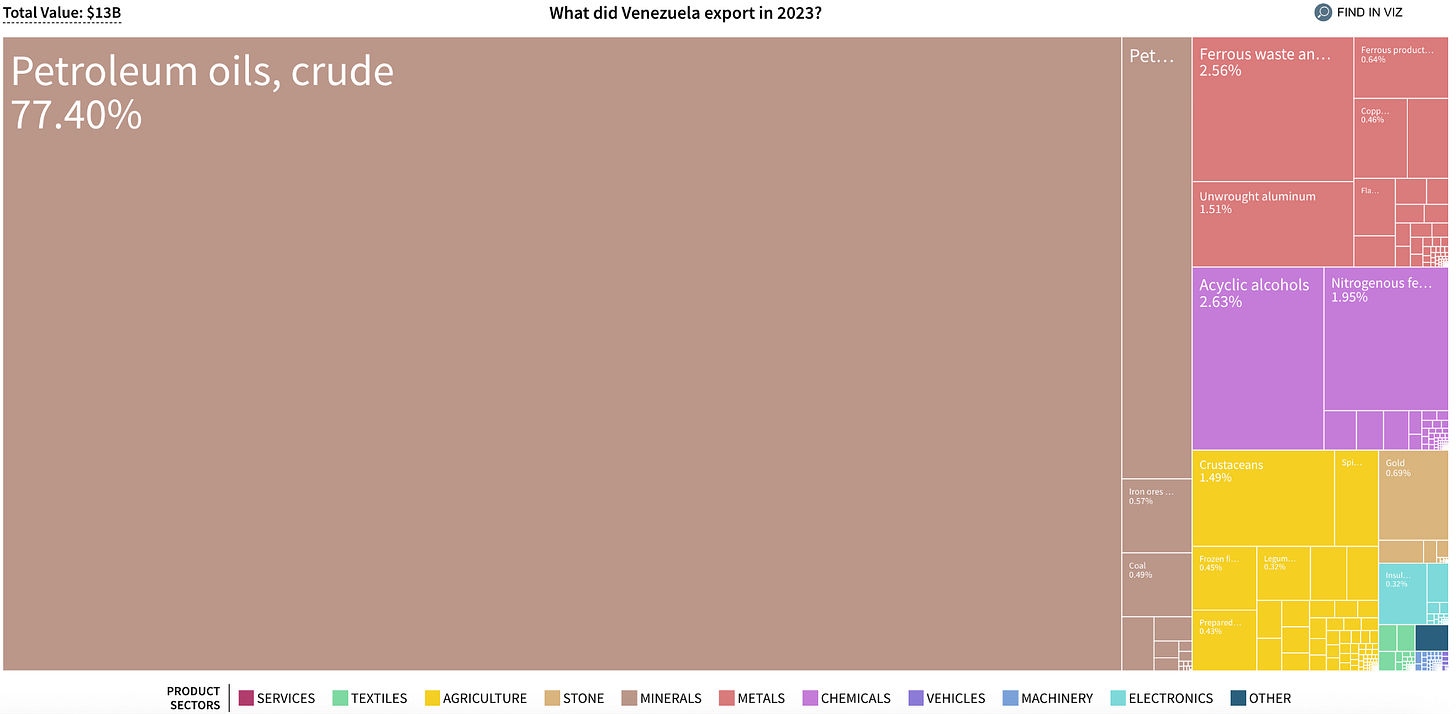

This is, of course, due to oil. Venezuela used to produce a lot, and now it doesn’t.

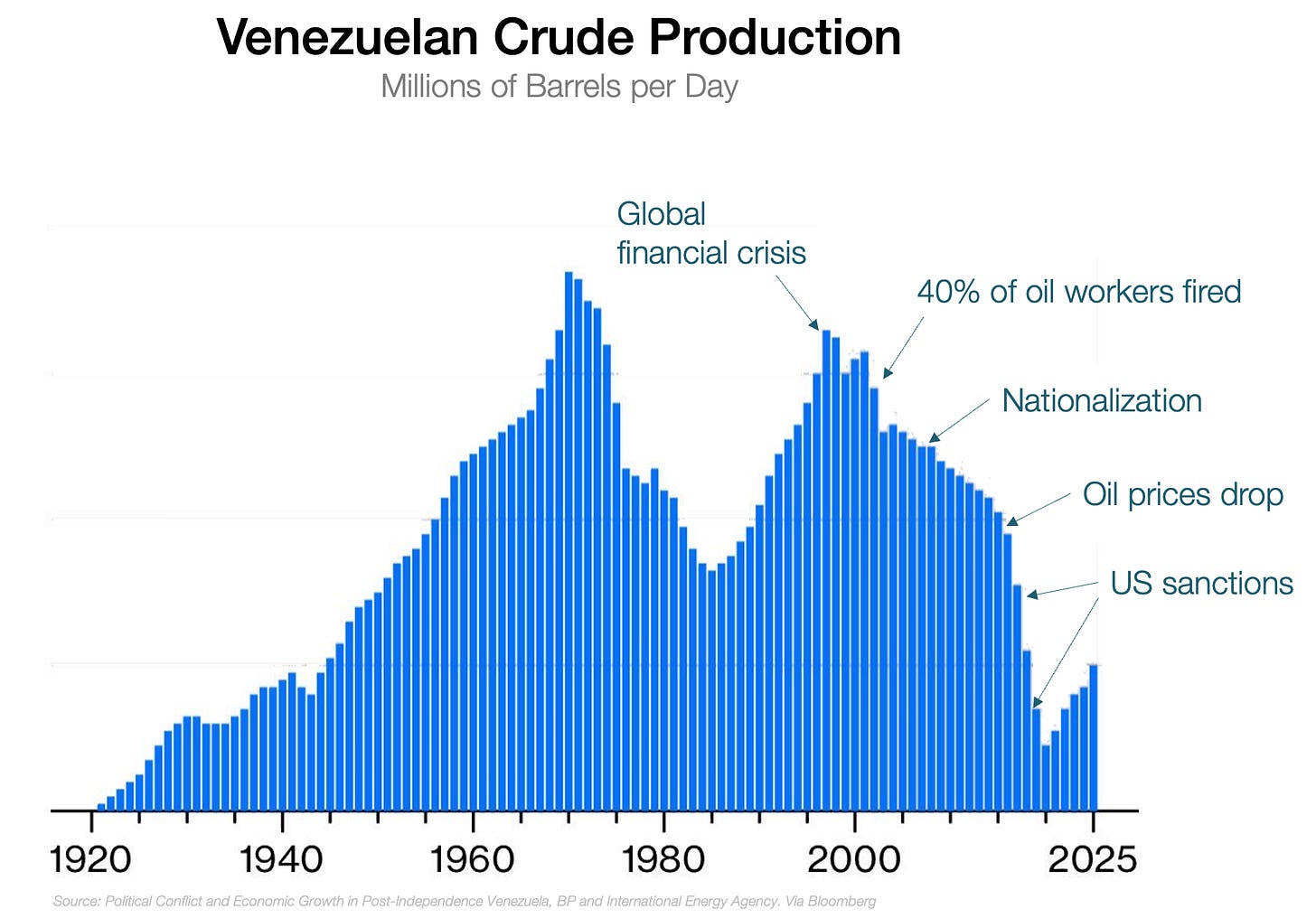

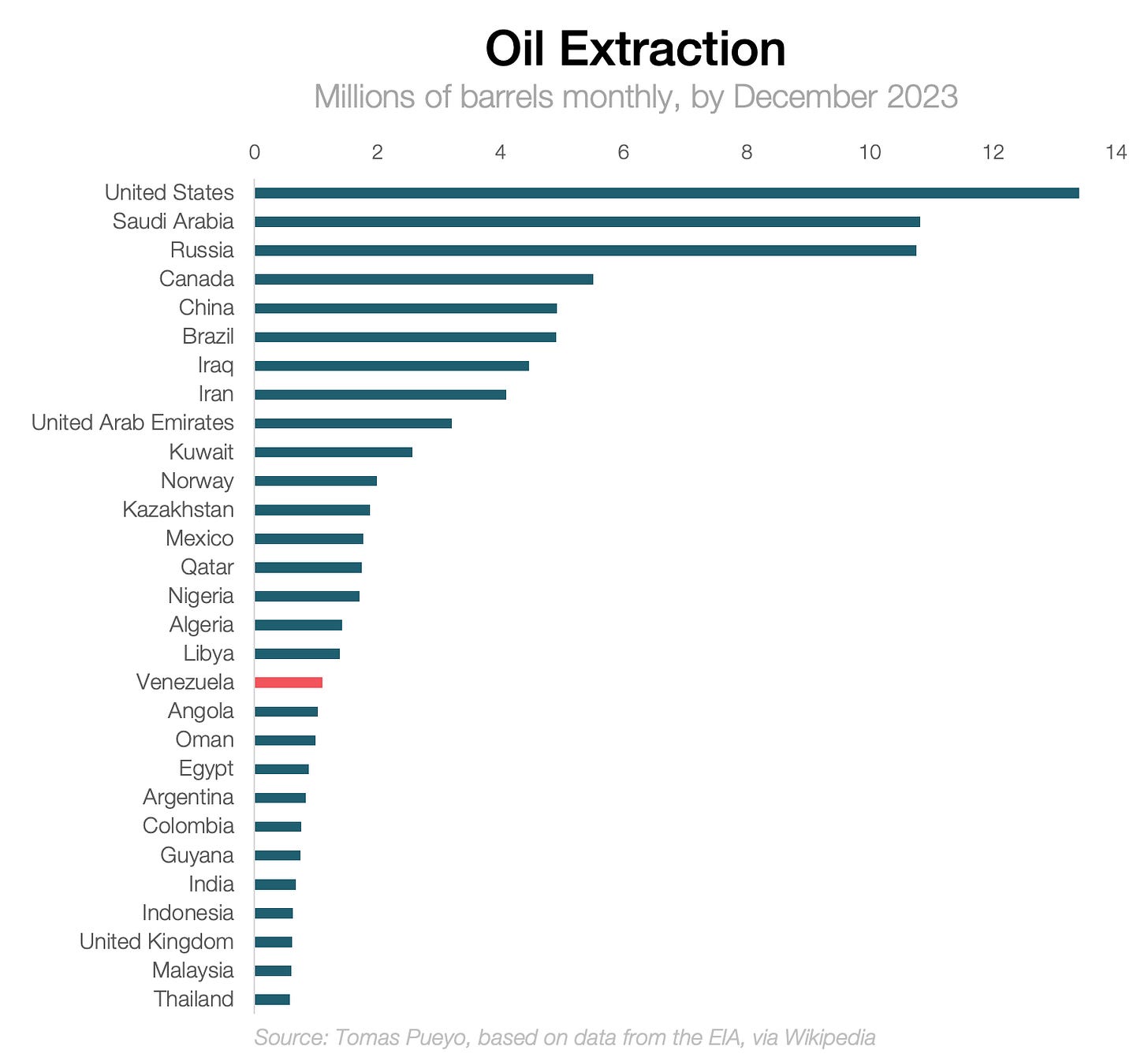

It was among the biggest producers in the world, and look at it now:

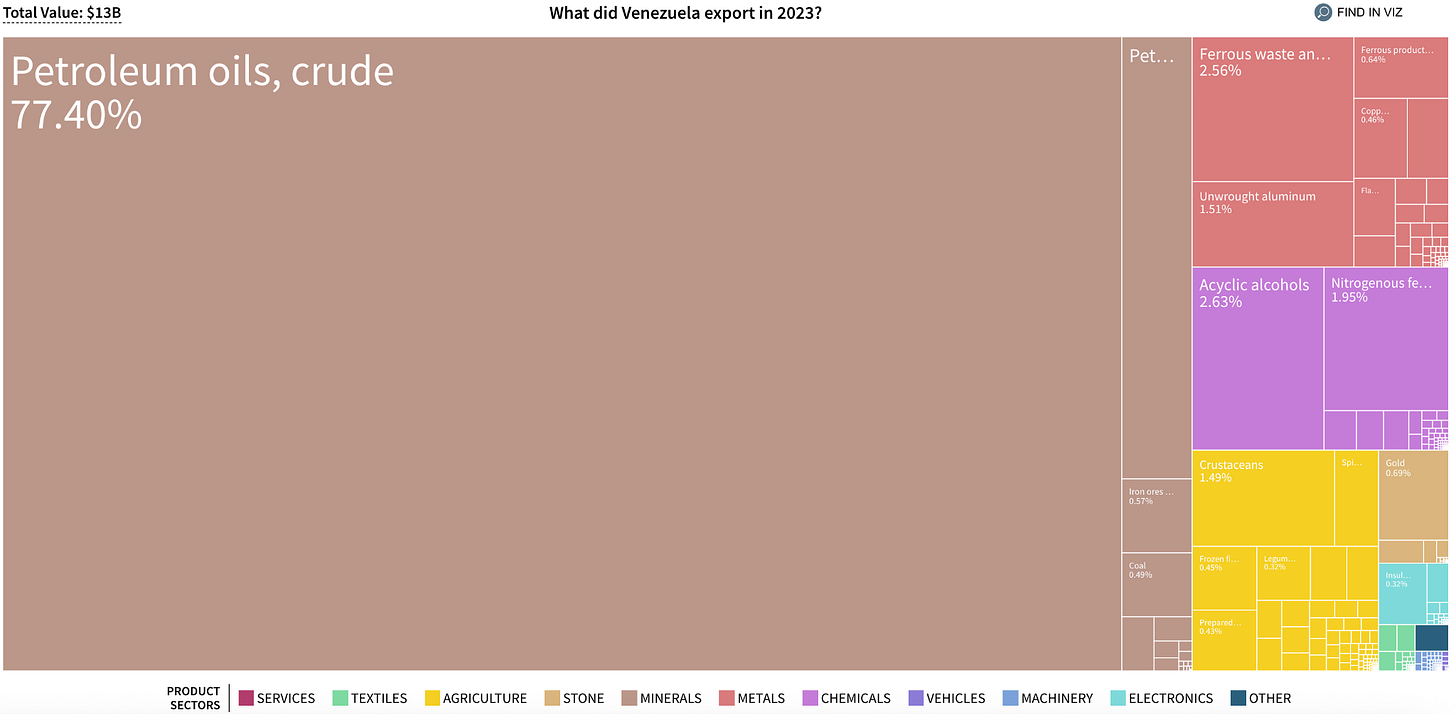

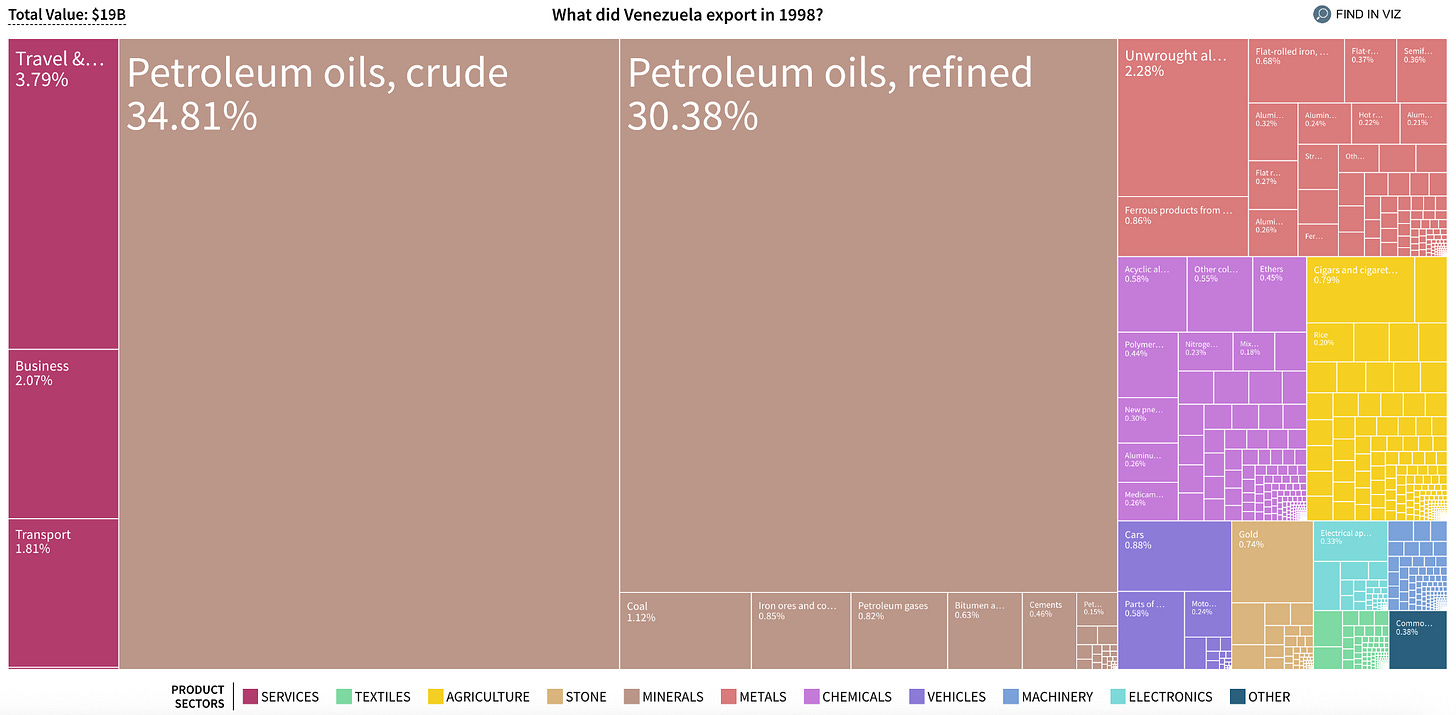

And Venezuela is extremely dependent on oil. In 2023, over 80% of its exports were oil and its derivatives:

There’s a reason for this: The Venezuelan economy was not well developed outside of oil because its geography is unforgiving.

Venezuela’s Difficult Geography

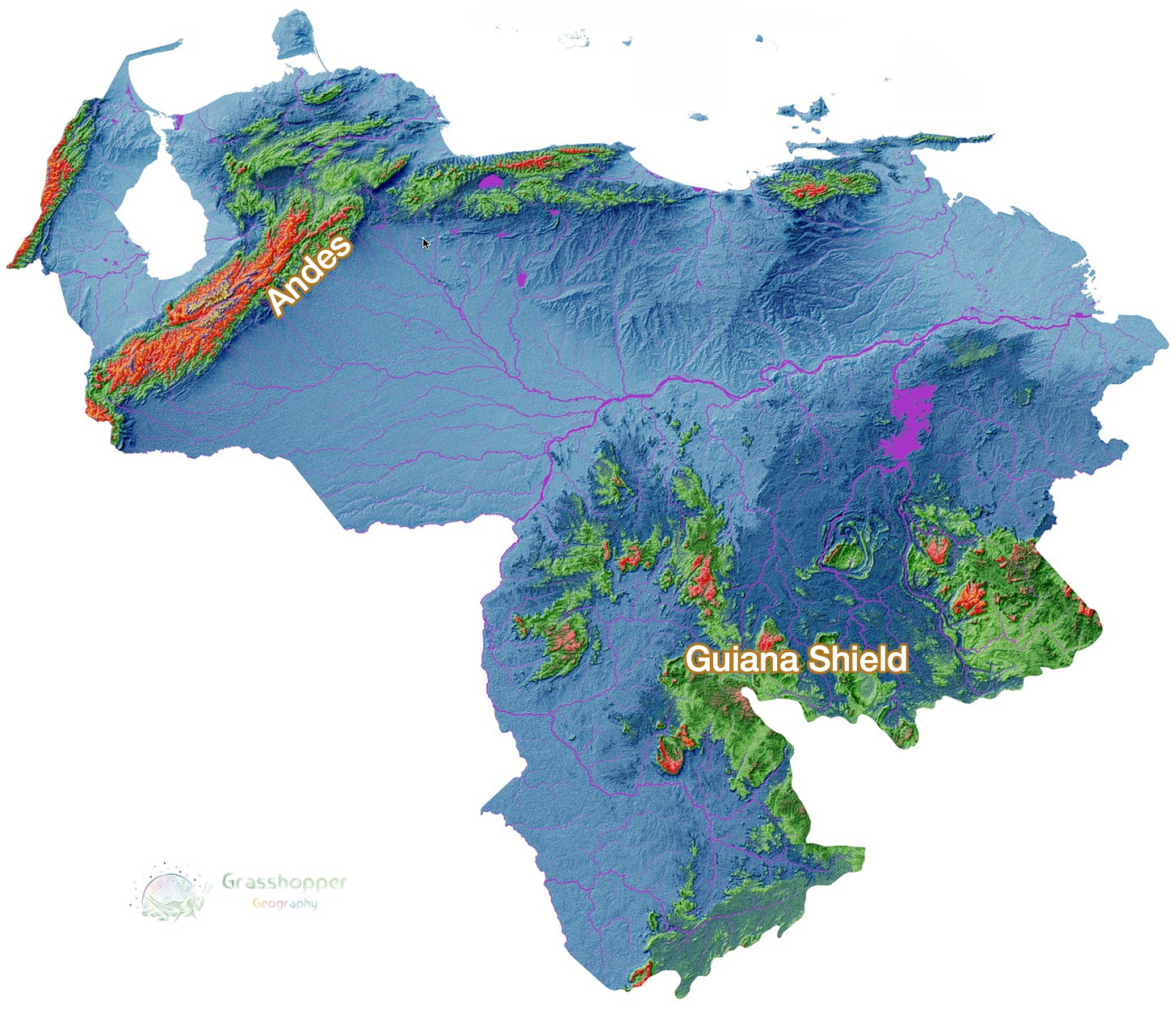

Here’s an altitude map:

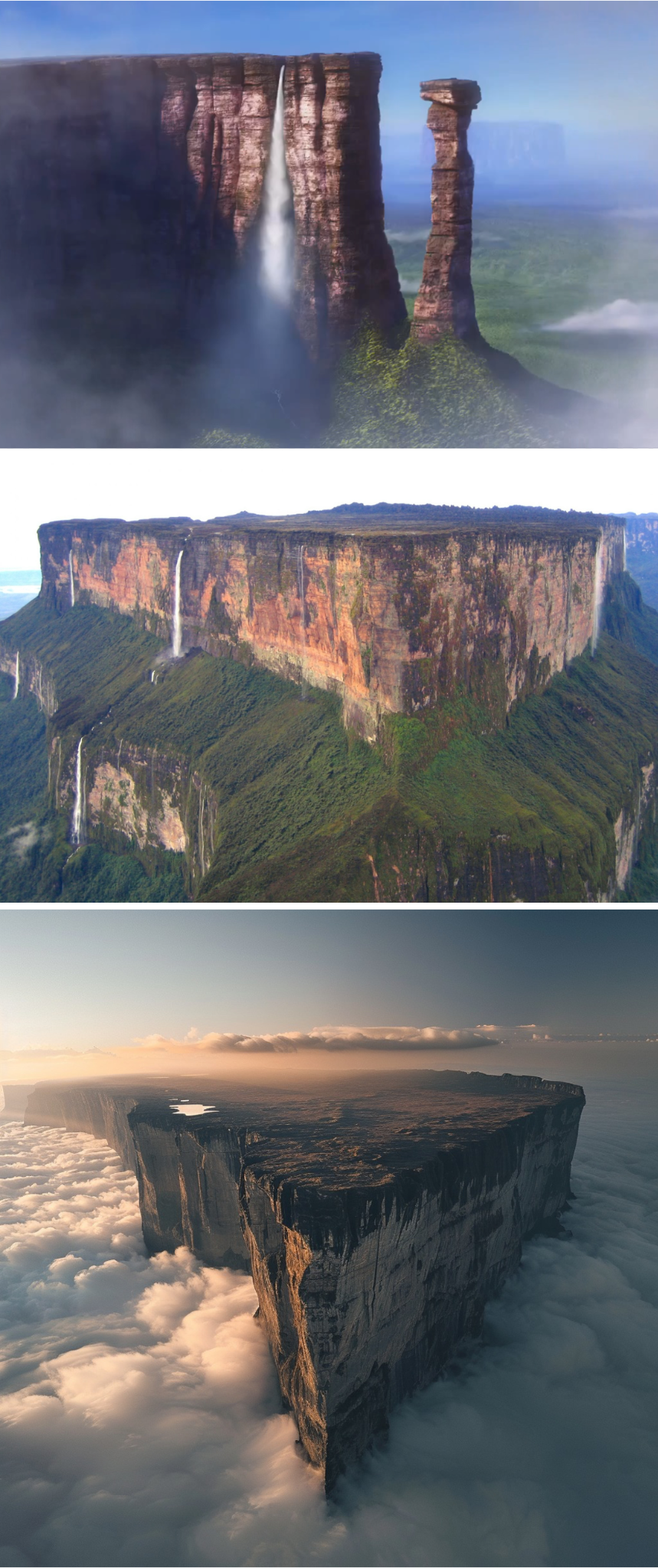

Venezuela is mostly flat, with two big mountain ranges: the Andes in the northwest (extending up the north coast), and the Guiana Shield in the southeast. That shield is where you can find the famous Tepuis:

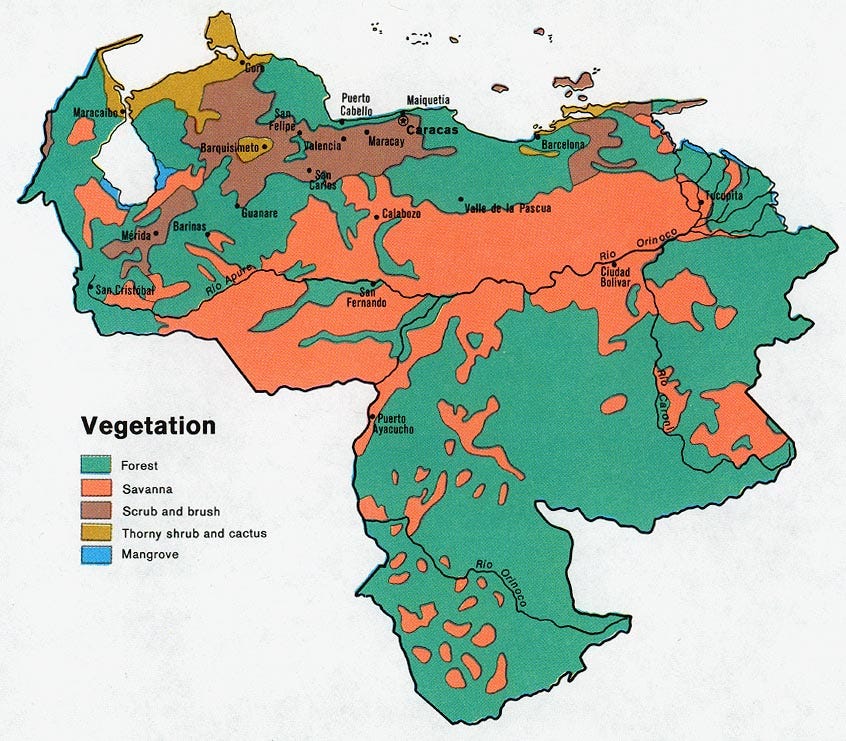

And since Venezuela is just above the equator, half of it is covered by jungle. Here’s a satellite map:

Here’s what the jungle looks like:

The vegetation:

The savanna in the middle is the Orinoco River Valley, what Venezuelans call the Llanos.

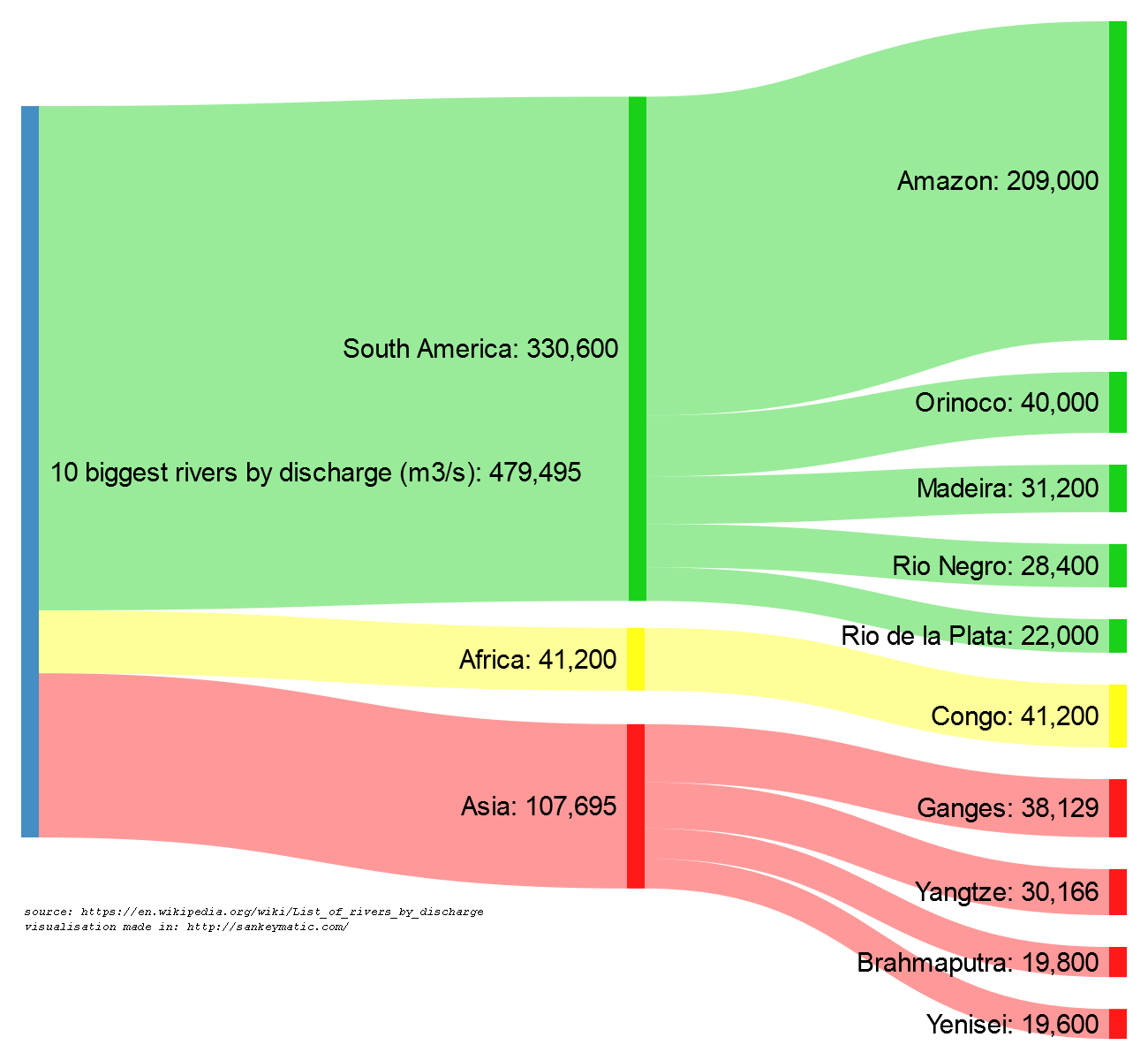

People don’t realize how big a deal the Orinoco is: It’s the 3rd biggest river in the world by discharge volume!

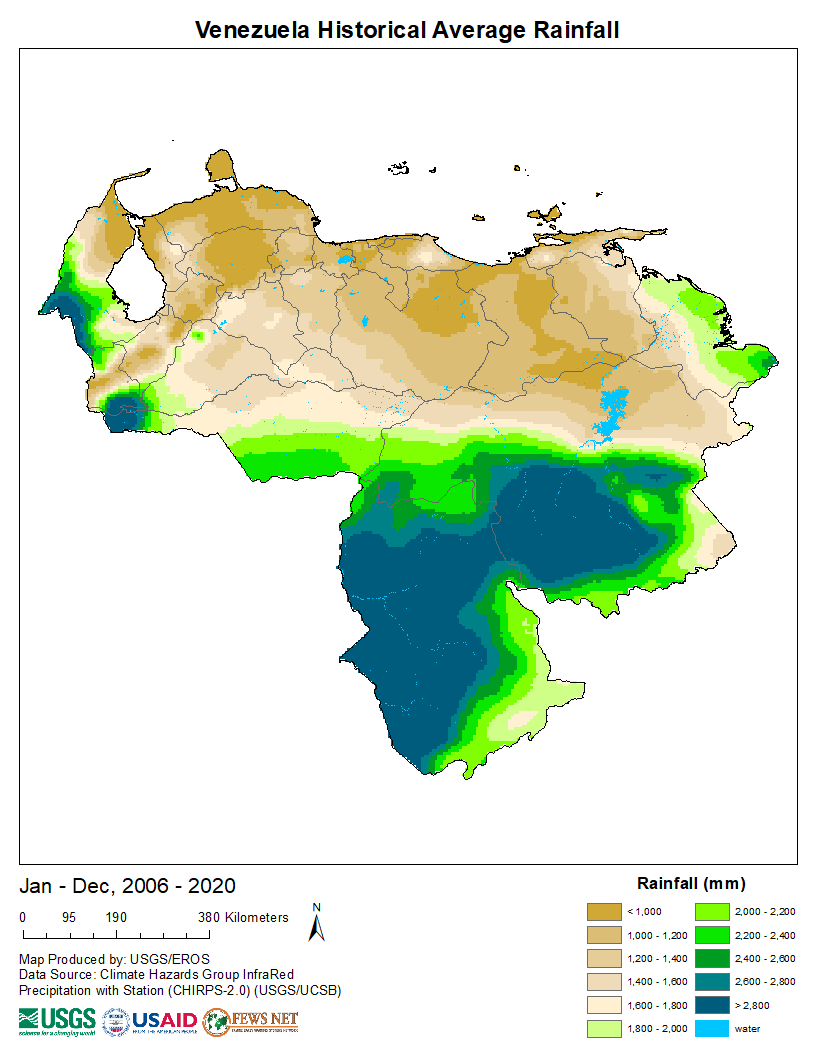

That’s because the same equatorial rains that feed the Amazon also feed the Orinoco, through the funnel formed by the Andes and the Guiana Shield.

On paper, that valley looks great because it’s flat, it has a river to bring sediments, and there’s some rain, but not too much, so soil leaching is limited.

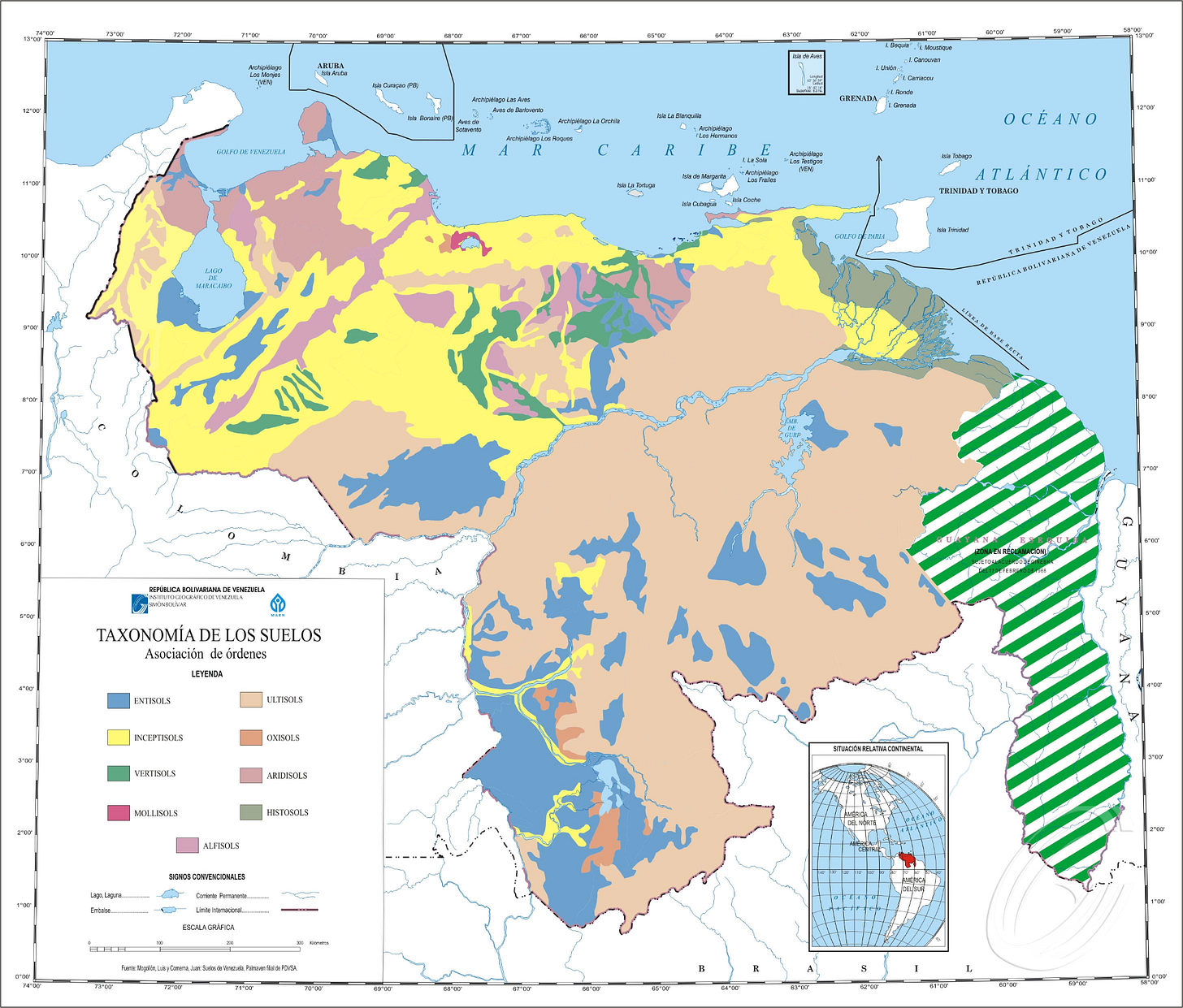

Unfortunately, the soil is terrible:

This is because the Guiana Shield is super old and close to the equator, so it’s been stripped of nutrients for eons, and any sediments that are deposited in the Orinoco Valley from there don’t add much fertility (hence the infertile ultisols, in brown on the map above). It’s also why the Andes side of the Llanos is a bit more fertile (yellow).

Brazil is in a similar situation, with old, infertile land. But they’ve spent billions improving it, and now they’re an agricultural superpower. Venezuela has not made a commensurate investment in its savannas.

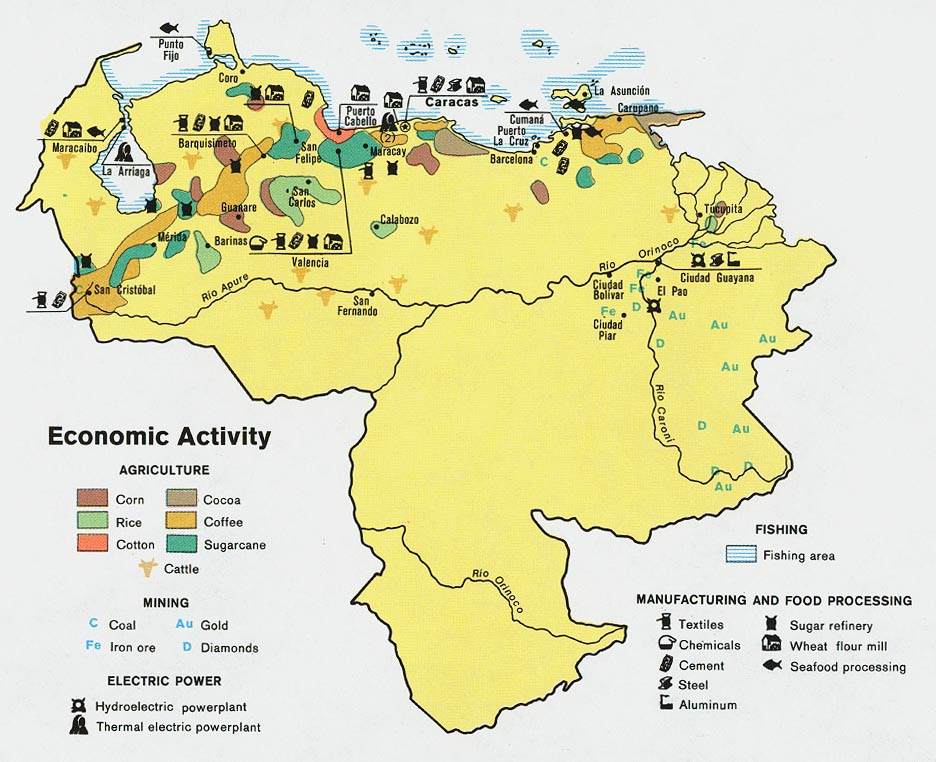

The result of all this is that most of the economy was historically concentrated in the northern mountains, while most of the Llanos is pasture for ranching:

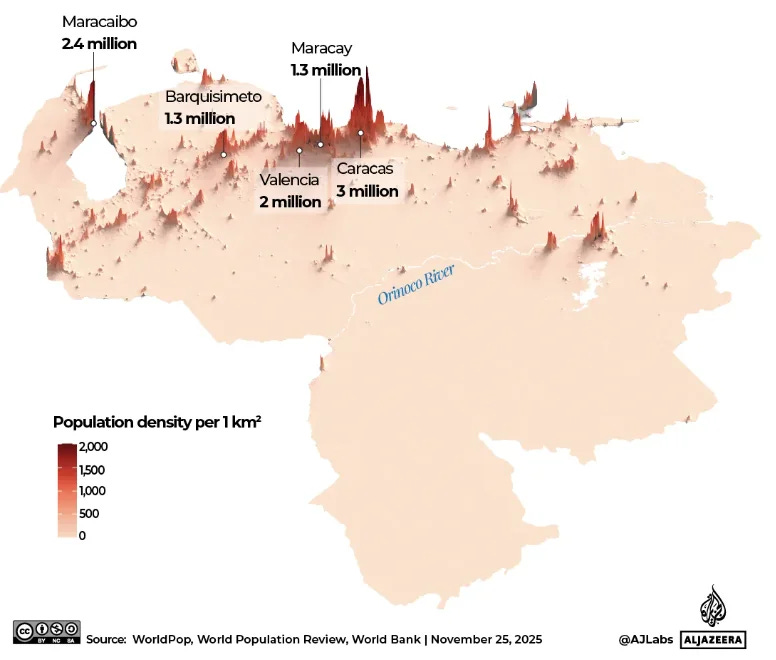

The population, like the economic potential, also concentrates in the Andes, in the valleys nested between mountains:

Here you can see a map of population density:

The people escape from the hot, humid, low-lying, infertile flatlands:

This is how Caracas ends up 900 – 1400m above sea level:

And why most of the Whites are on the mountains, while the jungle has a much denser indigenous population:

Of course, this is the tropical mountain trap we’ve discussed: Mountains are better suited for human settlement in hot climates, but mountains bring other challenges: Very expensive infrastructure, less trade, less communication, more poverty.

If we quickly summarize, Venezuela has:

Lots of hot, humid jungle, which is nearly impossible to settle densely.

A hot savanna with bad soil due to millions of years of leaching, and which hasn’t received the investment needed to fertilize it.

The mountains, where most of the economic activity lies, which is disadvantaged because of high transportation (and hence trade) costs.

Luckily, Venezuela has a lot of oil.

Venezuela’s Oil

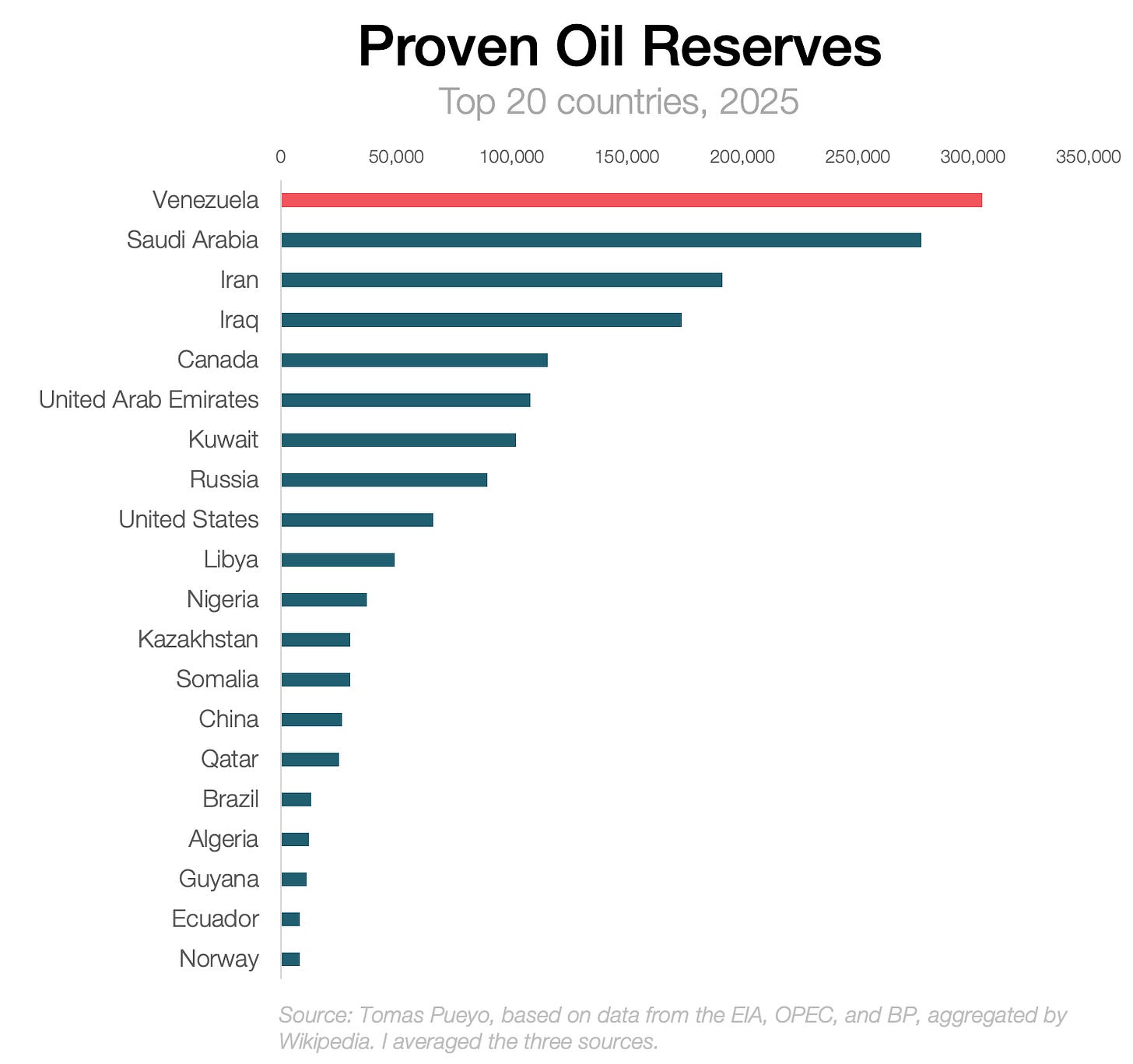

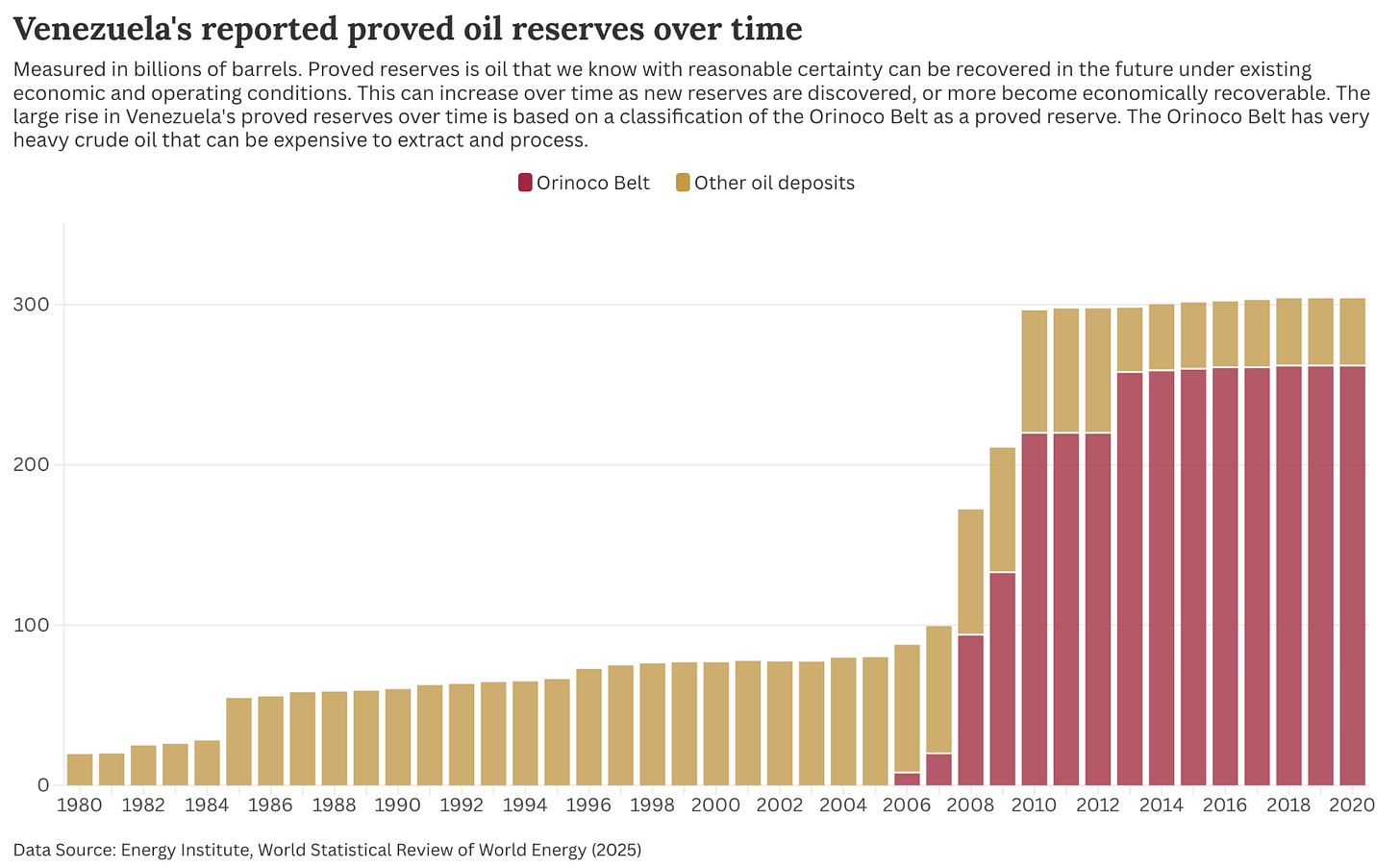

When I say a lot, I mean a lot.

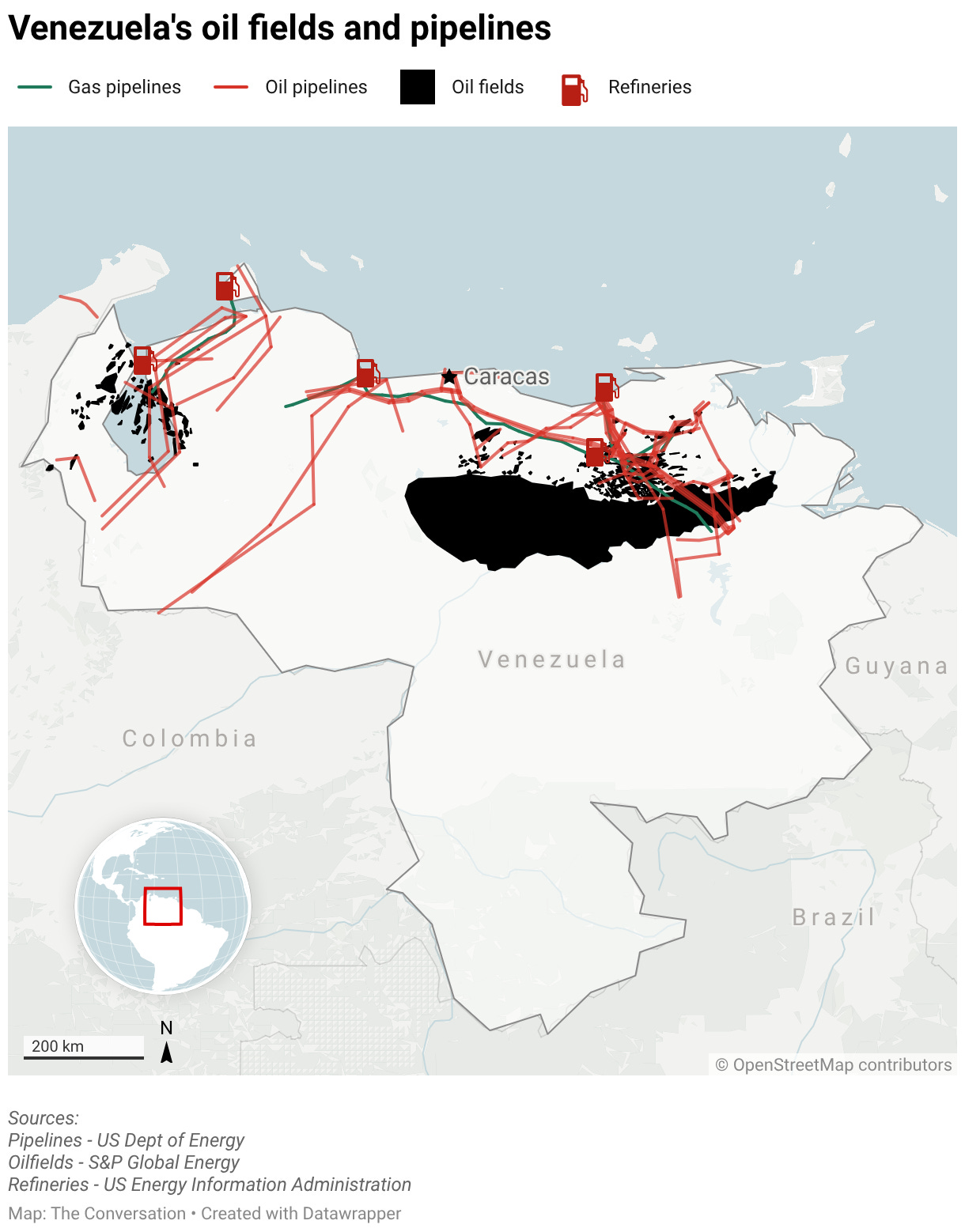

And where are they? Do you notice something?

There are a few reserves in Lake Maracaibo to the northwest, and more in the Orinoco Valley. The vast majority of these reserves is in the Orinoco Valley, and their discovery is reasonably recent.

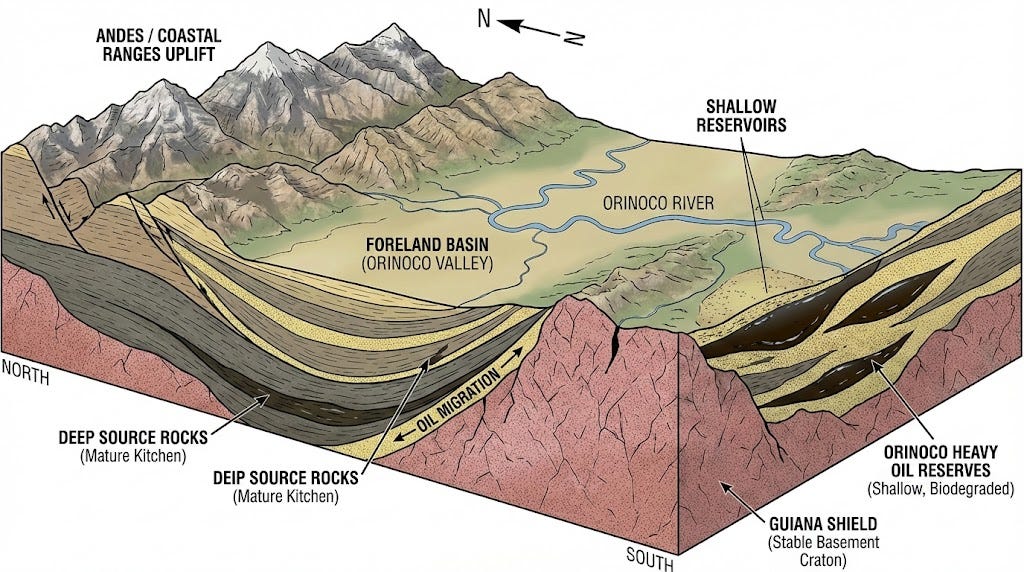

These regions have so much oil because they used to be shallow seas:

Shallow seas mean lots of animals, which fall to the sea floor over millions of years. Sediments from the Andes and Guiana Shield later covered these layers of dead animals, increasing the pressure and temperature, which create oil and gas.

But how did the Orinoco oil fields become the biggest oil reserve in the world? As the Pacific and Caribbean Plates hit the South American Plate, mountains rose, and the oil basically flowed southeastward until it hit the Guiana Shield.

This movement trapped the oil in the sands of this region close to the surface… Close enough that rainwater could filter in and carry the lighter types of oils away with it. Also, temperature dropped enough, and this was close enough to the surface, that bacteria ate some of the oil—the parts it could, the lighter oils.

The result? Yes, Venezuela has the biggest reserves of oil in the world, but that oil is very heavy and in sands.

This matters a lot: It’s why Venezuela is currently poor.

The Impossible Oil

Remember this graph?

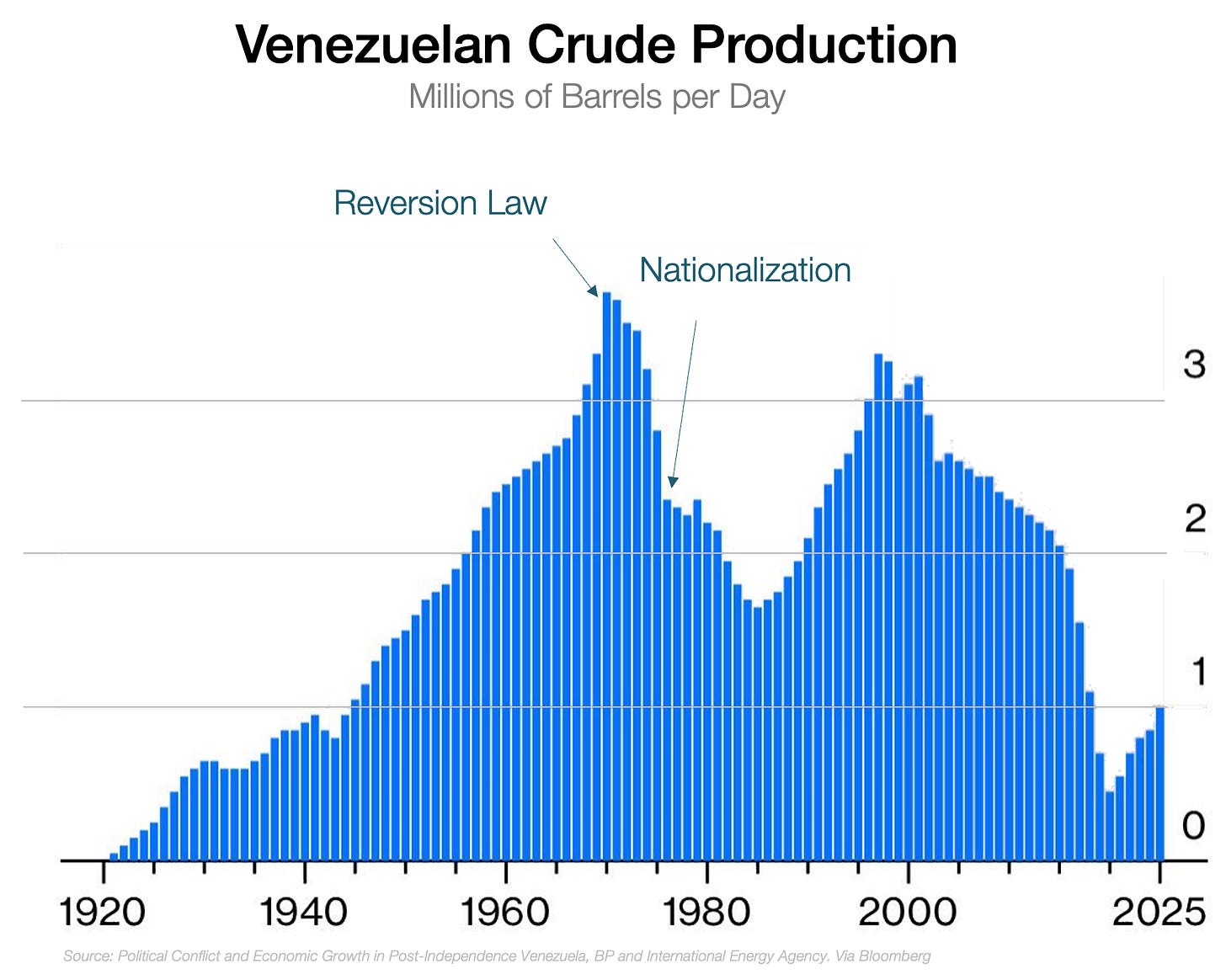

Notice it has two peaks, one in 1970, and the other in 1997. Why?

In 1971, the Venezuelan government nationalized the gas industry and passed the Law of Reversion, which stated that all the assets, plants, and equipment would revert to Venezuela without compensation upon the expiration of the concession, slated for 1983. Knowing that they were about to be nationalized, and that they would lose their investments, oil companies stopped investing. In 1976, Venezuela simply nationalized the industry.

It’s worth stopping here for a second. Between the 1970 peak and the trough in the 1980s, Venezuela reduced production by about 2M barrels per day, worth $200B today.

Eventually, the Venezuelan oil company recognized that the heavy oil sands were very hard to process and that it couldn’t do it alone. It invited big international oil companies to work together in joint ventures. As those companies came back, oil production started growing again.

After the 1997 financial crisis, demand for oil plummeted, and with it oil prices. As they reached $9, the price of oil was so low that it was above the cost to extract the expensive Venezuelan oil, so all investment was cut, leading to production shrinking a bit.

But then Chávez took office in 1999, and serious problems started again:

He fired 40% of the Venezuelan oil company’s workers in 2002 during a strike.

He diverted money dedicated to oil investment into social programs.

In 2007, he expropriated the oil companies once again.

Chávez died of cancer in 2013, so he never witnessed the consequences of his mistreatment of the oil industry. His successor, Maduro, did:

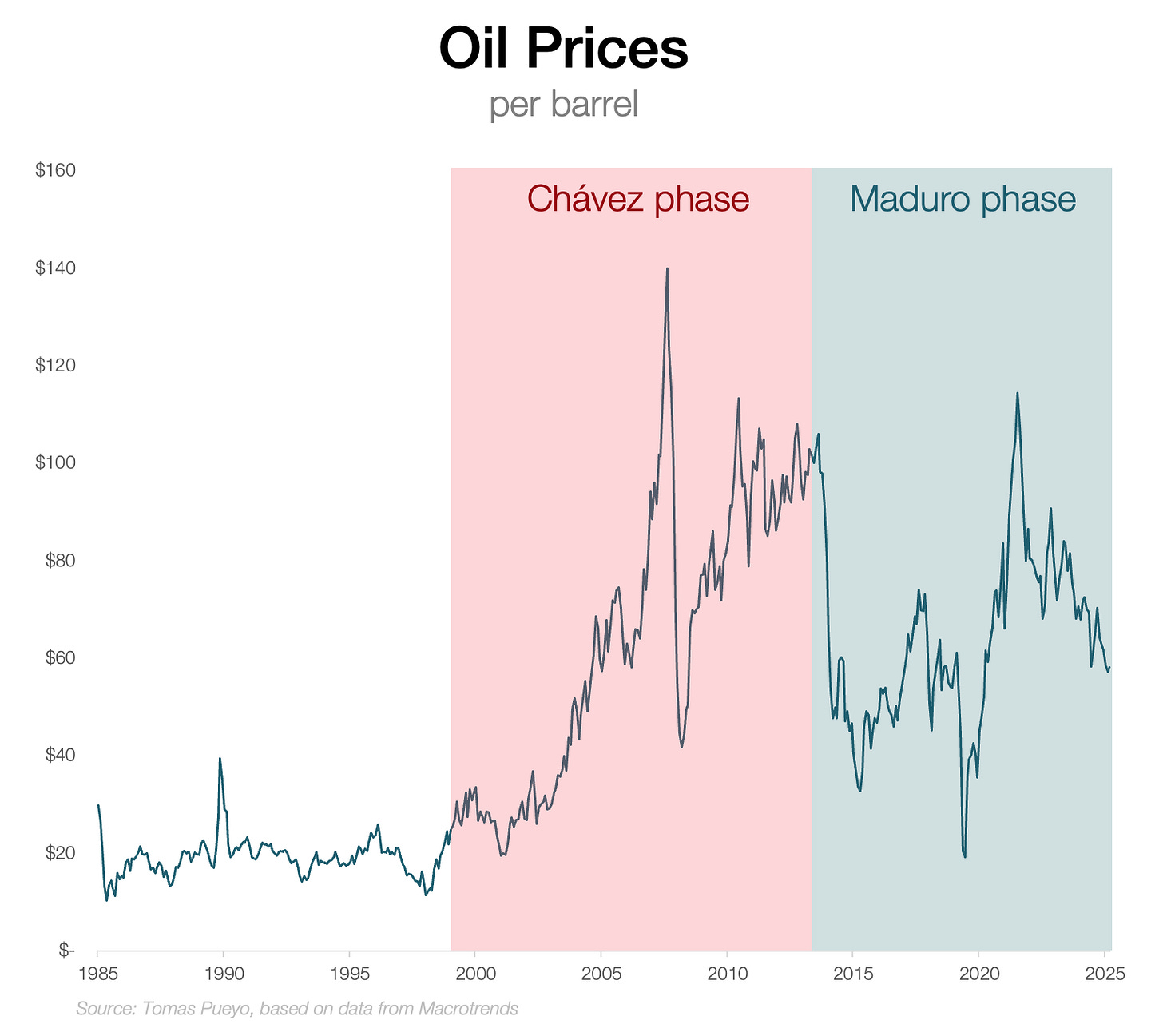

Just as Chávez died, oil prices crashed, making many of the expensive heavy oil sands economically unviable, especially without the know-how of big international oil companies. So the volume of oil that Venezuela could extract dropped, too.

After two decades of mismanagement, Venezuela’s oil industry is in tatters, and it’s very difficult to turn it around.

But it gets worse!

Resource curse

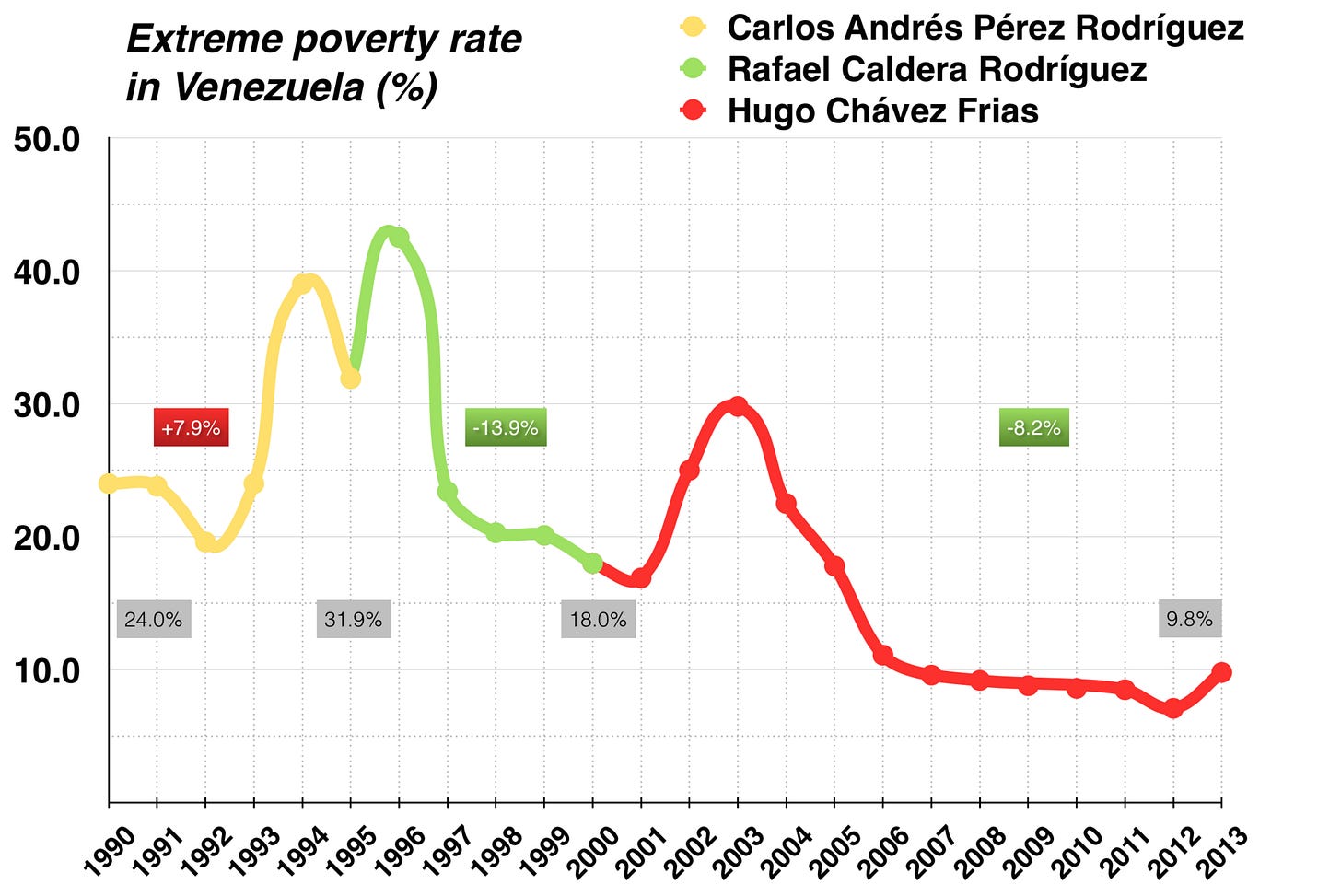

Venezuela is the typical victim of the resource curse:

A country discovers a resource that’s valuable and easy to extract and control.

So the government takes it over and milks it.

It can afford to waste money, so it does. Waste increases. Corruption increases.

Prices in the country rise. Other industries become uncompetitive and die.

Let’s start with exports. On the eve of Chávez’s power takeover, crude used to be 35% of the country’s exports and its derivatives another 32%, adding up to 67%.

In 2023, over 80% was oil and its derivatives, most of it crude, as the refining know-how had vanished from the country.

But note also how other exports shrank even more, due to the resource curse: They were crowded out by bad political management and the weight of the oil economy. You can nearly tell the entire history of Venezuela’s socialist authoritarian experiment with these four charts:

Chávez:

Took over the country when it was producing a lot of oil.

He was lucky to catch the entire upswing in global oil prices.

Thanks to that, the country’s GDP expanded. But risk was increasing, as the economy grew more and more dependent on oil.

Government spending outpaced oil income, and as a result the country was running deficits.

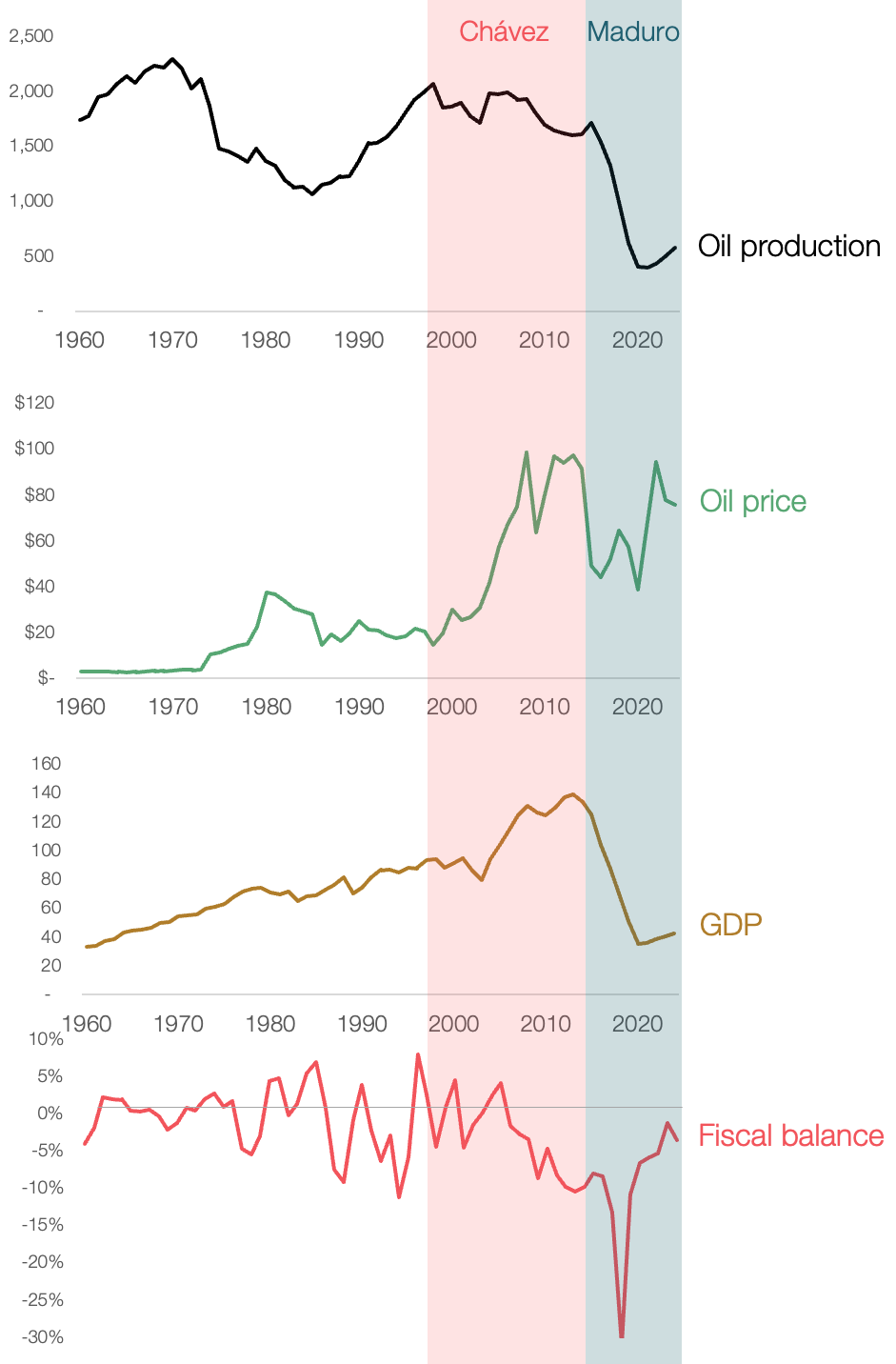

To be clear, some of that spending was beneficial for many people. The poverty rate went down quickly:

But this approach is always short-term. Just as Maduro took over:

Oil prices crashed.

Which accelerated the drop in oil production.

Together, these two tanked oil income.

In an economy almost entirely dependent on oil.

And the government ran massive deficits.

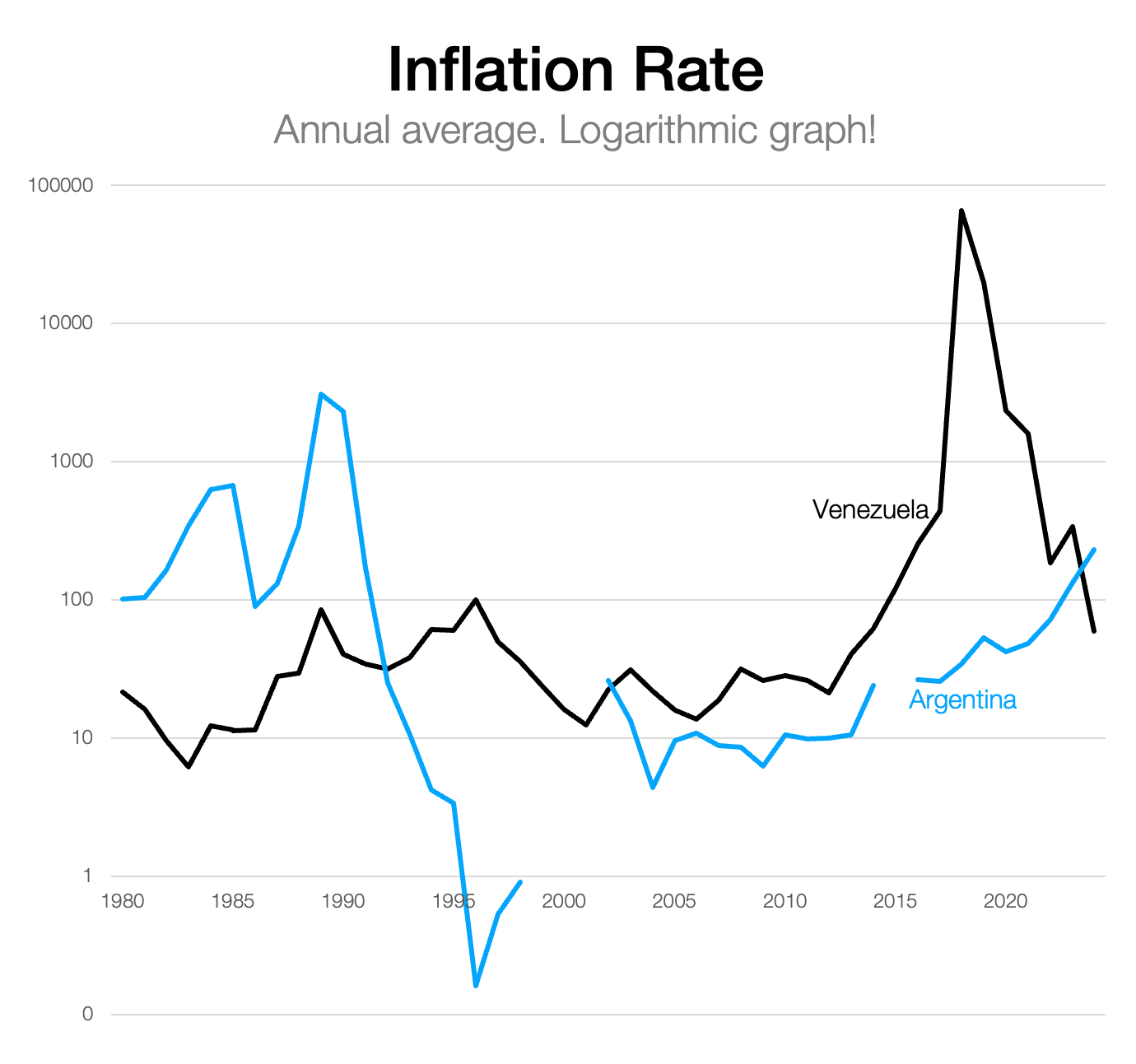

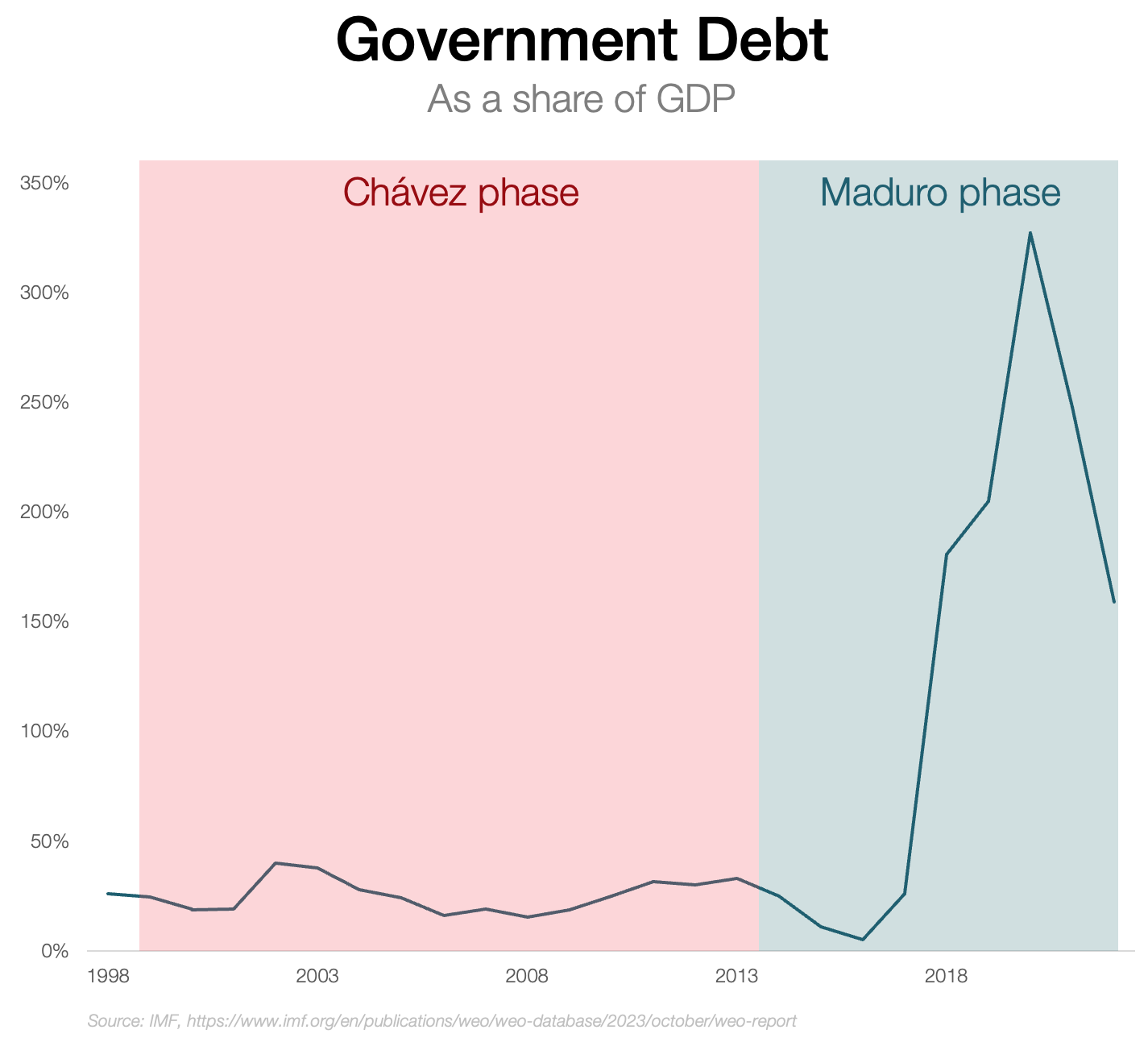

And what happens when you run massive deficits? You have to either reduce costs, issue debt, or print money. Since reducing costs is anathema in a socialist country, it issues debt.

But that works in the short term too, until the country defaults, after which nobody wants to lend money anymore.

Without income, with high expenses it didn’t want to slash, and no way to get more debt, the country did the only thing left: print money. Here’s a chart on inflation:

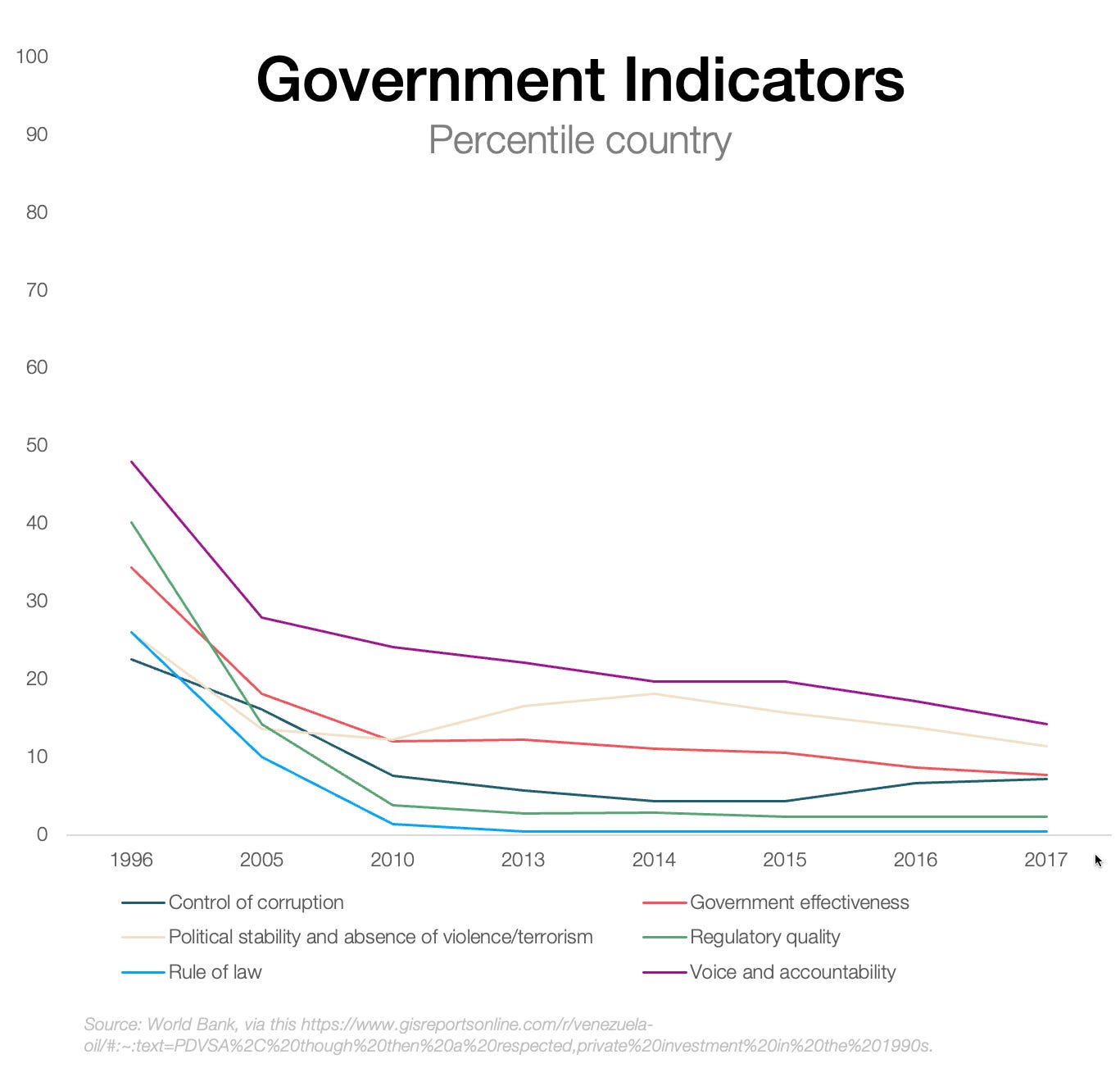

The resource curse is not only economic, but also of governance:

Let’s put some color to that, with the words of Jeff Kazin, the head trader of the US food multinational Cargill in Venezuela:

Cargill was/is the leading producer of critical staple ingredients such as flour, pasta, vegetable oil, and rice in Venezuela. I [had] a front row seat to the damage a kleptocracy did to innocent people.

The government took over our “minute rice” facility at gunpoint because we were “gouging” the nation’s poor. The government was never able to run the plant. It never ran again. It was returned years later with no equipment inside.

There are 1000’s of generals in the army. They are each given a slice of the economy to loot. The large number of generals made it difficult to organize a coup against the regime.

The government opened grocery stores and sold staples below the cost we sold them to the government. In theory they used petro oil money to lower grocery prices. Our regular grocery outlets were forced out of business. When the government demanded we sell them products below cost we simply had to shut down. The populous became ever more dependent on the government handouts.

Dollars: We needed dollars to buy raw materials like wheat from places such as the US and Canada. The government periodically allocated dollars that could only be spent on raw materials and freight. Eventually, only local companies willing to pay bribes received dollar allocations. Several facilities closed due to lack of raw materials.

My employees liked working for Cargill. The office was an armed compound with access to a gym, high-speed internet, global communications, and a weekly box of basic staples. Cargill provided a safe and secure environment, if only during working hours.

Employees became very close to others inside their apartment buildings. Going out on the street among a desperate population was not advisable.

I needed wood pallets for feed. We tried to export wood pallets to swap for grain. We refused to pay the bribes required to export the pallets.

I once tried to set up a closed-loop wheat-planting to flour-mill supply chain.

The seed wheat was stolen for food.

When we tried to ship seed wheat in containers via US donors, there was no way to get it out of the port without it being stolen.

Livestock: Our feed business completely collapsed. Even if you could raise a pig, you could not defend it from being stolen. Armed people were hungry.

Employees: In the end, my highly skilled team, along with other highly educated people, chose to leave. Cargill often found jobs for them in other Latin American countries. The regime was more than happy to see well-educated people leave. Helping these employees secure high-quality, stable jobs after fleeing remains one of the best things I ever did in my career. No one remembers millions in trading earnings.

This is a short list. In my opinion the first money spent needs to happen now and it needs to be food. The US is already on the clock. The current regime does not care if it starves the population. The orgy of theft will accelerate if they believe their days are numbered. VZ should be an outstanding customer of US-grown agricultural products. Rice, bread, wheat, vegetable oil, etc. Feed the people first.

Jeff Kazin

Former head trading Cargill

Hence pictures like this:

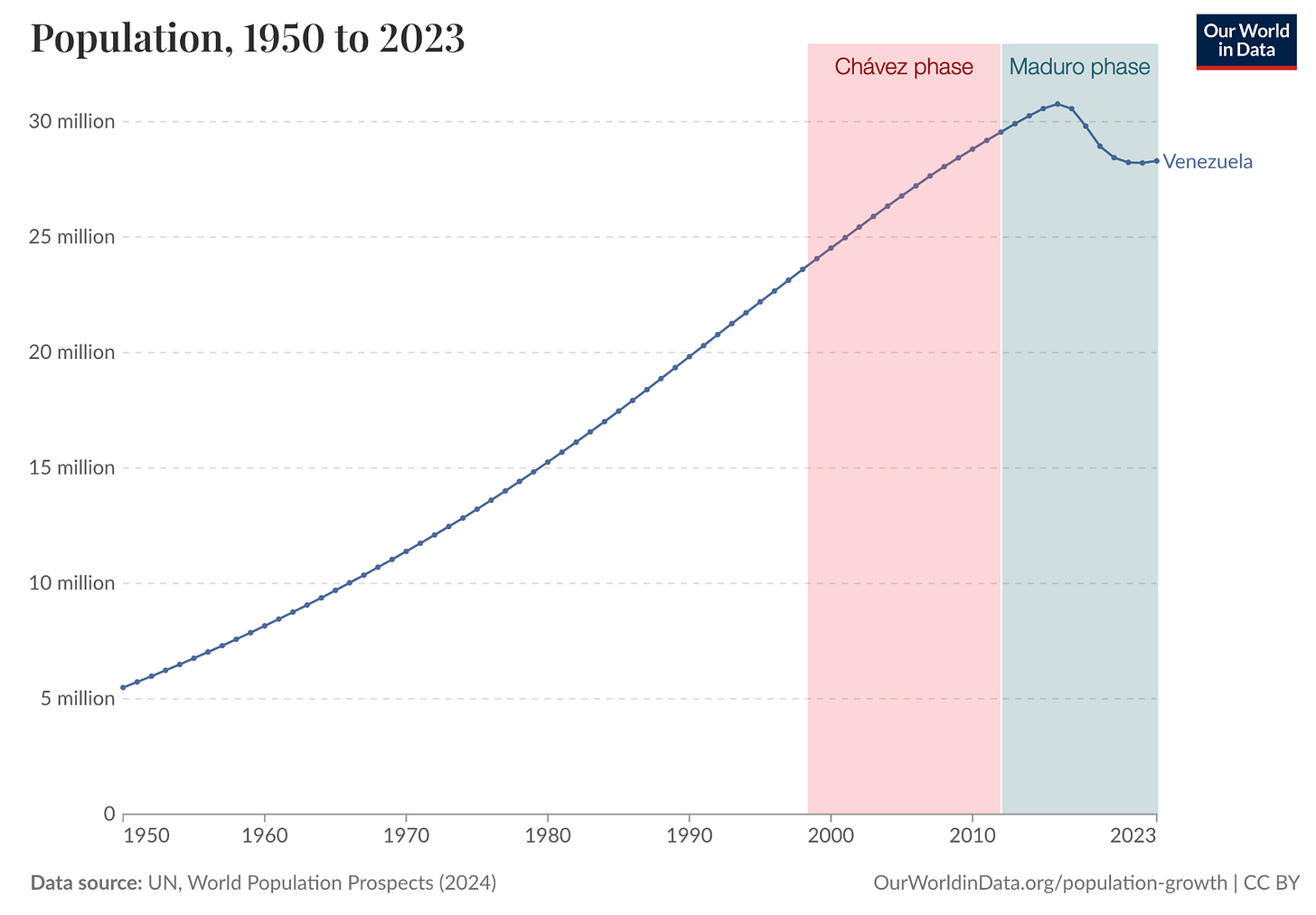

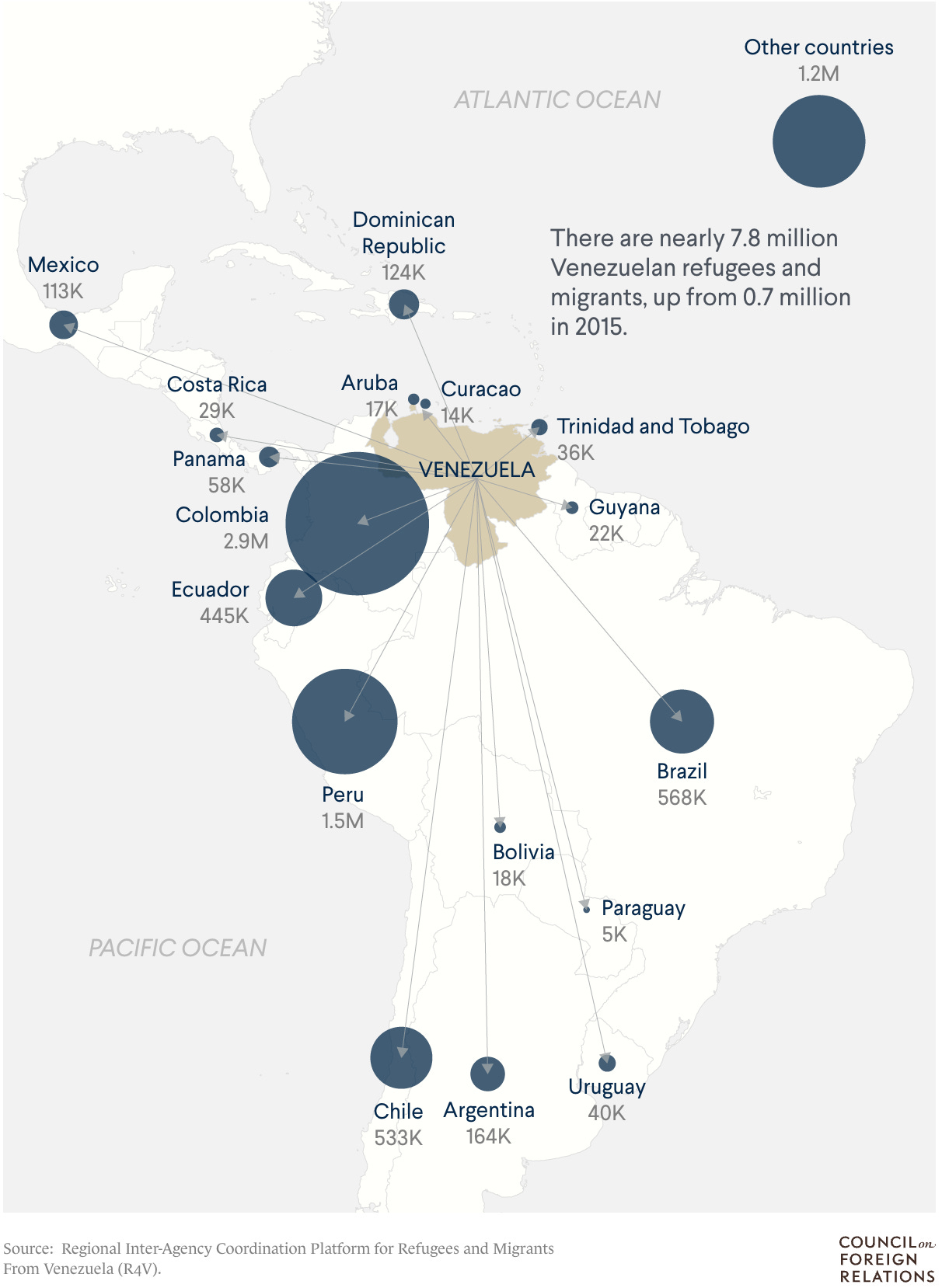

So of course, with this economic and political situation, a lot of people left.

They mainly went to countries across Latin America:

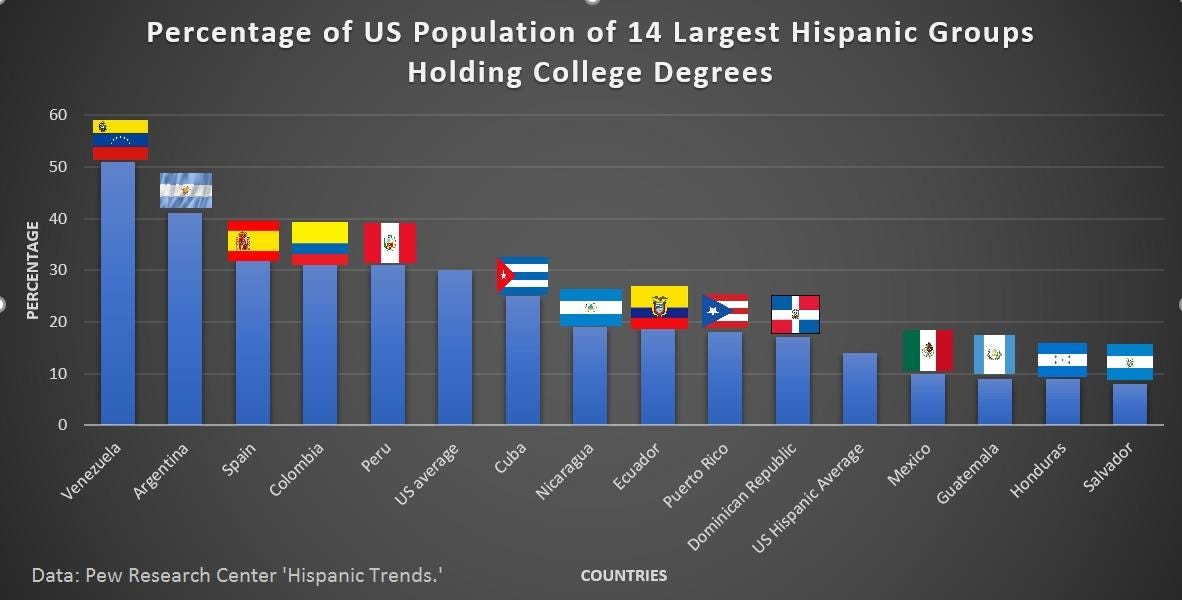

What’s special about Venezuela is that a huge chunk of its emigrants were elites.

This is why communism never works:

The government takes from those who produce to distribute to the rest

Because people don’t like when the government takes their assets, the government must become authoritarian to force the expropriations.

Those producing the most leave, to avoid both expropriations and authoritarianism.

Because those producing most left, production diminishes, and everybody is poorer eventually.

The rest has no incentive to work, as there’s no benefit in it.

Once the country has become authoritarian, the gun owners become the new elites and loot from the rest.

In effect, communism replaces productive elites with looting elites.

All this reminds me a lot of Argentina:

It also had a big resource that depended on international markets—agricultural products.

The government also took as much control of it as it could, to milk the cow.

It also overspent socially during bonanza years.

This also meant huge deficits in years when international commodity prices were down.

Which ended up with debt defaults and heavy inflation.

The Devil’s Excrement

So if we look back at what has happened with Venezuela:

The country’s geography is pretty bad, with infertile tropical jungle and savanna, and people crowded in the mountains, which increases all costs.

It has one massive asset: oil.

But that oil is hard to get and refine, so it’s expensive and requires foreign expertise.

Oil resulted in a textbook example of the resource curse:

A destruction of other industries

Terrible mismanagement and poor governance

Mismanagement pushed out foreign oil companies, so Venezuela’s oil output shrank along with its value added: refined oil exports became crude exports.

When international oil prices crashed, Venezuela lost both volume and price, so its income tanked, and with it the entire economy.

Since state expenses didn’t shrink proportionally, the country entered into deficit, then debt, then default, then money overprinting, and hyperinflation, finalizing the total destruction of the economy.

In such a clusterf*, the elites escaped, brain-draining the country, and further destroying its economy.

Oil is the devil’s excrement.—Juan Pablo Pérez Alfonzo, Venezuelan minister primarily responsible for the creation of OPEC (along with Saudi Arabian minister Abdullah Tariki), 1976

This is the context needed to really understand what’s happening in Venezuela today. In the next article:

What will happen with Venezuela and the Venezuelans?

Was Maduro’s capture legal or legitimate?

How does that affect the US, Russia, and China? Greenland, Cuba, Taiwan?

How does it rewrite the rules of the world?

Just a point that should be important to mention. Things started to go wrong in Venezuela in 1983, when the full economy collapsed during the Venezuelan Black Friday. After that came all the austerity measures and the collapse of the banking system in the 90s. When Chávez took over, in 1998, Venezuela was already in a pretty bad situation; then the Chavismo made it even worse (which seemed impossible at the time).

PS: You do mention it in the article, but I think it might be relevant from the start (and then clarify later).

A single export country with a history of authoritarianism and coups fails to diversify, allows rampant top-level political and economic corruption, fails to initiate timely public-sector investment and stimulus, elects and maintains back-to-back dictatorships, fails to reign in rampant inflation, and is economically crashed by import sanctions from the world's most powerful nation...

...and they thought it would work?

You can't make socialism-capitalism cake* work in that situation. The government will always become increasingly desperate to ensure it maintains control, and strongman authoritarianism always results.

* Socialism-capitalism cake: Supporting your people with a basic welfare system to keep people from falling through and becoming resentful, and encouraging a top layer of diverse, mostly-free-market capitalism, kept reasonably fair through regulations, to encourage productivity and innovation.

Too much government involvement and you get soul-crushing authoritarianism and a stangant, inflexible society, regardless of political alignment. Too little government involvement and you get another Gilded Age with robber barons, zero-sum-game wealth and poverty, and society-destroying monopolies.