Why Is Argentina Poor?

The root of its economic mismanagement

Encuentra este artículo en español debajo del inglés.

Javier Milei’s party just won Argentina’s legislative elections. Why? How can we understand his policies? Will they lead to Argentina’s return to wealth and greatness? Or will they lead it straight back into yet another cycle of mayhem? Should he do anything differently? To answer these questions, we need to understand why Argentina is poor today.

But doing so is one of the hardest tasks in economics. Argentina’s poor performance is among the most discussed topics in international economics. So I have tried to synthesize what research tells us, and I found an illuminating way to doing it was comparing the development of Argentina with those of Japan, Taiwan, South Korea, and China (covered here), because all these countries did very similar things but ended up with dramatically different outcomes. This helps us isolate the few differences that probably caused Argentina’s demise. In any case this is such a complex issue that I’m certain to have made mistakes. If you find any, please correct me in the comments or by responding to this email.

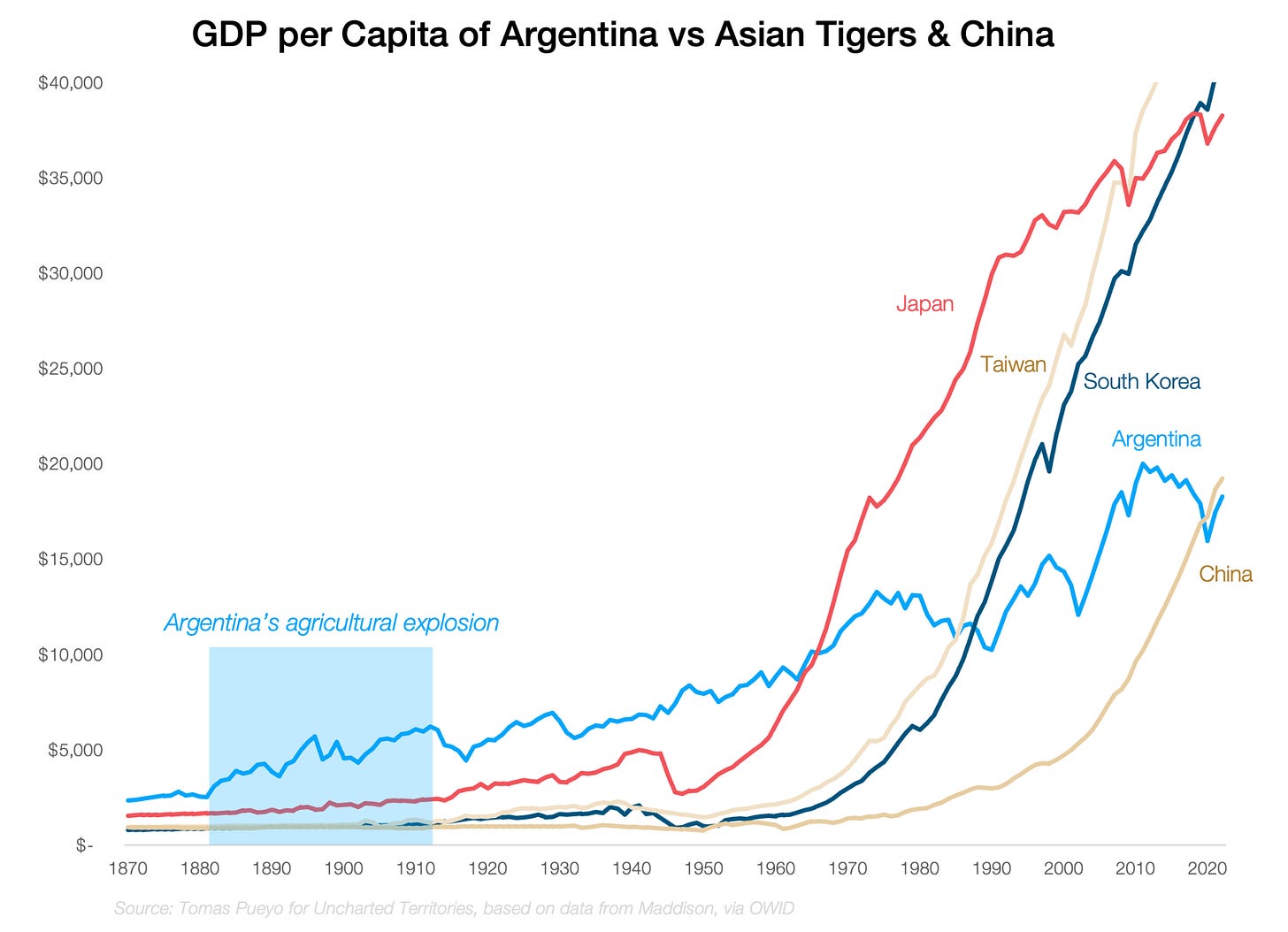

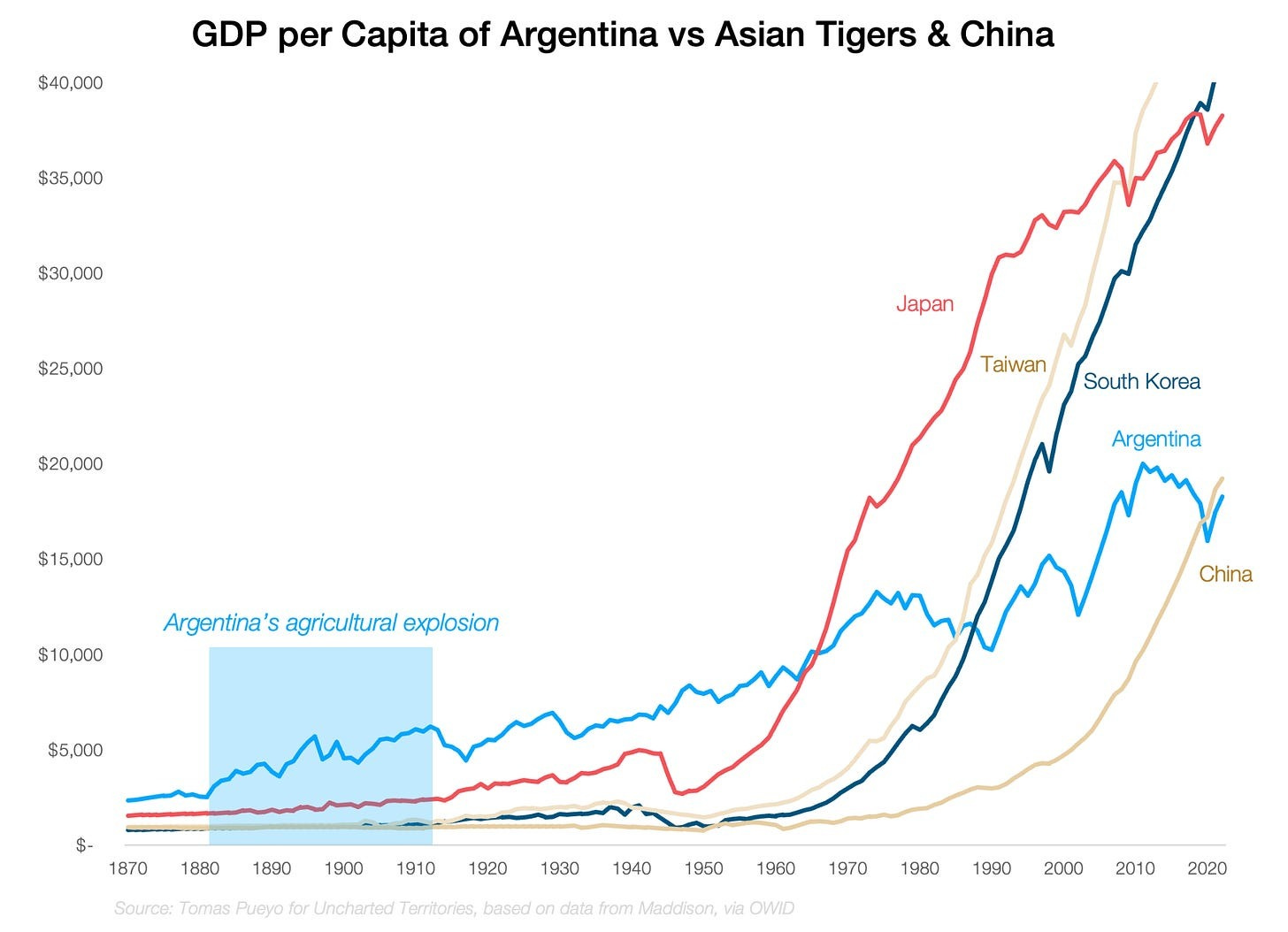

Around 1900, Argentina was 2x richer than Japan, and over 4x richer than Taiwan, South Korea, and China. But all these countries are now richer than Argentina. Why?

This is a much more interesting story than it appears, because the similarities between these countries’ economic policies are uncanny. But there are a few crucial differences that caused the Asian countries to grow while Argentina stagnated. So let’s look first at what the Asians did, and then compare with Argentina, to see where everything went wrong and why.

How Asian Tigers Developed

I explained it in detail here, but here’s the summary.

1. Agriculture

The land in Taiwan, Japan, and South Korea was concentrated in few hands. The first thing they did after WW21 was to redistribute it. This gave many people jobs and increased farm productivity, because farmers now owned the farm and its products, so they tried to improve both: They invested in machinery, better fertilizer, better grain, they didn’t overwork the land…

As farm productivity increased, these farmers were able to save money. Productivity increased enough to feed the country. The governments taxed farmers, but also frequently subsidized them through minimum prices for their crops, help procuring fertilizer, seeds… There was little food export, but what existed was heavily controlled and taxed.

Thanks to this, each country developed a broad base of farmers, increased their savings, and earned foreign income.

2. Industry

Once farming worked, these countries started redirecting the surplus to industries to develop them. They picked a few key industries and supported them in many ways:

They frequently applied import taxes to the foreign competition of protected industries. This is called infant industry protectionism.

They reduced their taxes.

They gave them cheap loans.

They got import licenses so they could import, and do so with limited taxes.

Crucially, they only did this to the companies that were growing fast and were able to compete internationally. Those that couldn’t compete stopped receiving cheap loans and were pushed to merge or fail.

3. Finance

Where did the money come from for these cheap loans? From the farmers (and other citizens), who couldn’t invest their money wherever they wanted. Real estate and stock markets were not accessible to them, and neither could they freely place their money abroad. They were forced to put the money in the bank with low interest rates. That’s the money that was then lent to industrial companies.

Also, the exchange rate was kept low, and inflation suppressed:

Exports were left untaxed, so there were a lot of exports. They brought foreign currency to their home countries (usually USD). They spent some in international markets (fertilizer, seeds, machinery…), and the rest they sold to buy local currency.

The central banks bought the USD. They printed local currency to buy it.

This would have led to inflation, so they sterilized this by emitting low-interest debt and forcing banks to buy it.

Foreign investment was limited. Since foreigners have foreign currency and sell it to buy local currency, they tend to appreciate the local currency. By limiting their investments, they limited this local appreciation.

Wage growth was kept low. Trade unions were pushed to accommodate this. This kept inflation at bay.

How Argentina Went Sideways

1. Agriculture

We saw in our two previous articles that Argentina’s geography is outstanding, and the country capitalized on it in its 1880-1910 agricultural boom:

Farmland expanded quickly

Many cattle ranches were replaced with crops, with the help of rapid mechanization and immigration2

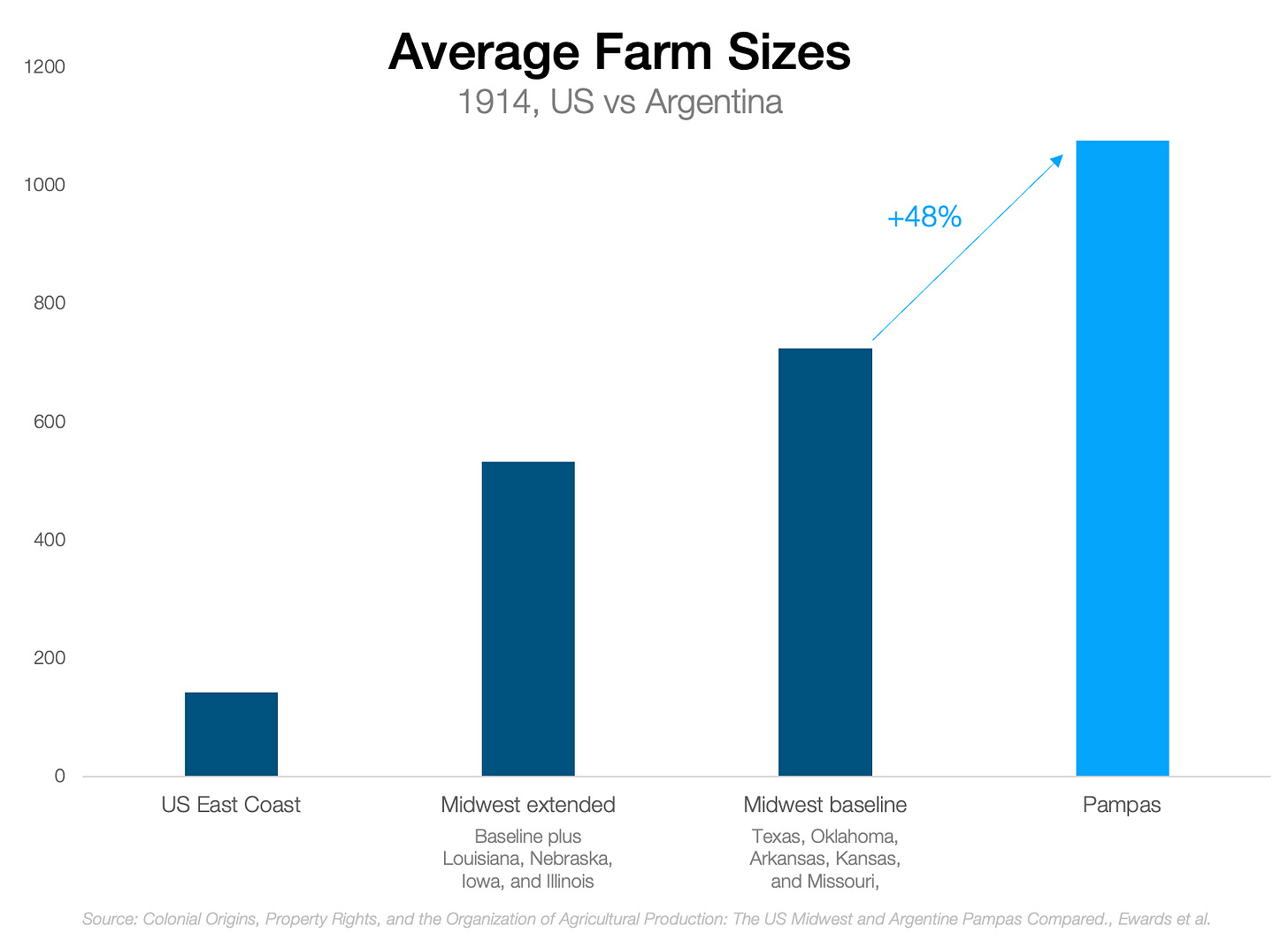

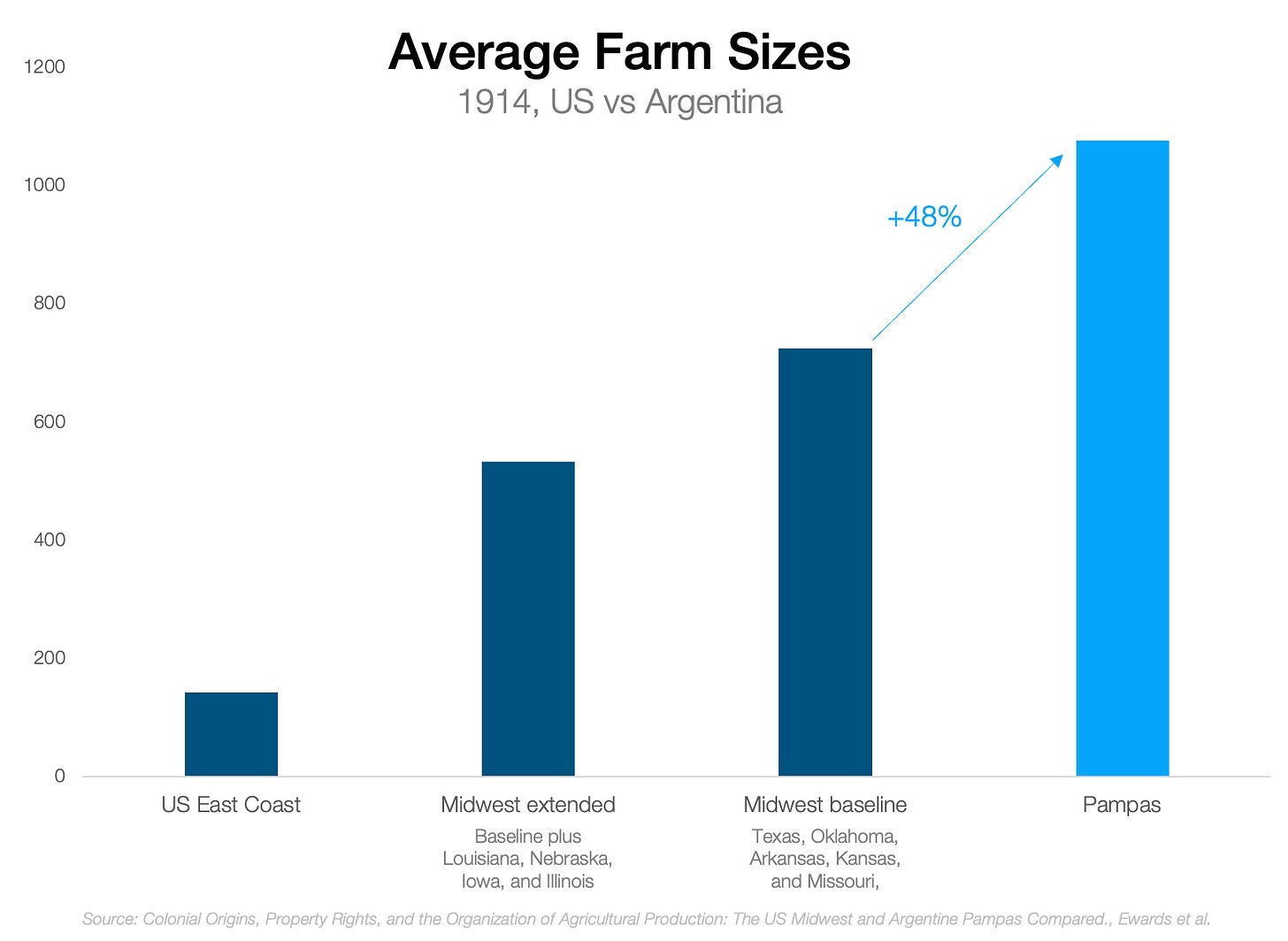

But here’s the original sin of Argentina: Farms remained highly concentrated.

This didn’t impact land productivity too much at first, because the landowners had an incentive to maximize their production and thus their exports.

However, since land was so concentrated, there wasn’t a broad base of farmers who could benefit. A few landowners gained outsized economic, social, and political power.3

This rising inequality caused a political backlash that didn’t happen in the Asian Tigers. This political pressure pushed governments to tax farming in a less productive way than Asian Tigers had.

Recall how Asian Tigers also taxed agricultural exports, but there were few, and they used most of that income to reinvest in farms. The biggest redistribution from agriculture to industry was indirect: by forcing farmers to save at the bank their wealth, which was then lent to industries.

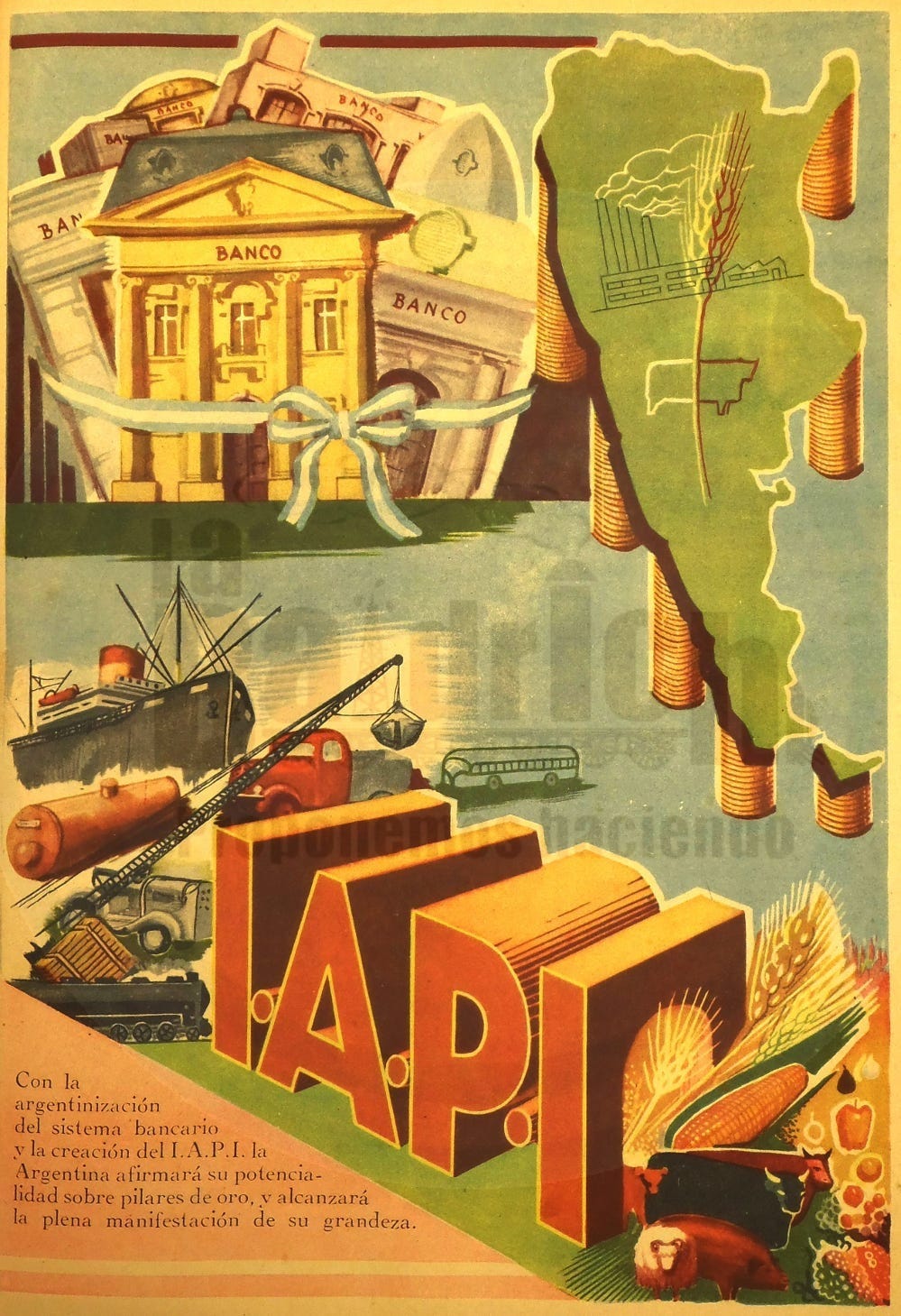

Instead, Argentina simply taxed agricultural exports. For example, the IAPI (Instituto Argentino de Promoción del Intercambio) had a monopsony on agricultural exports (it was the sole buyer by law).

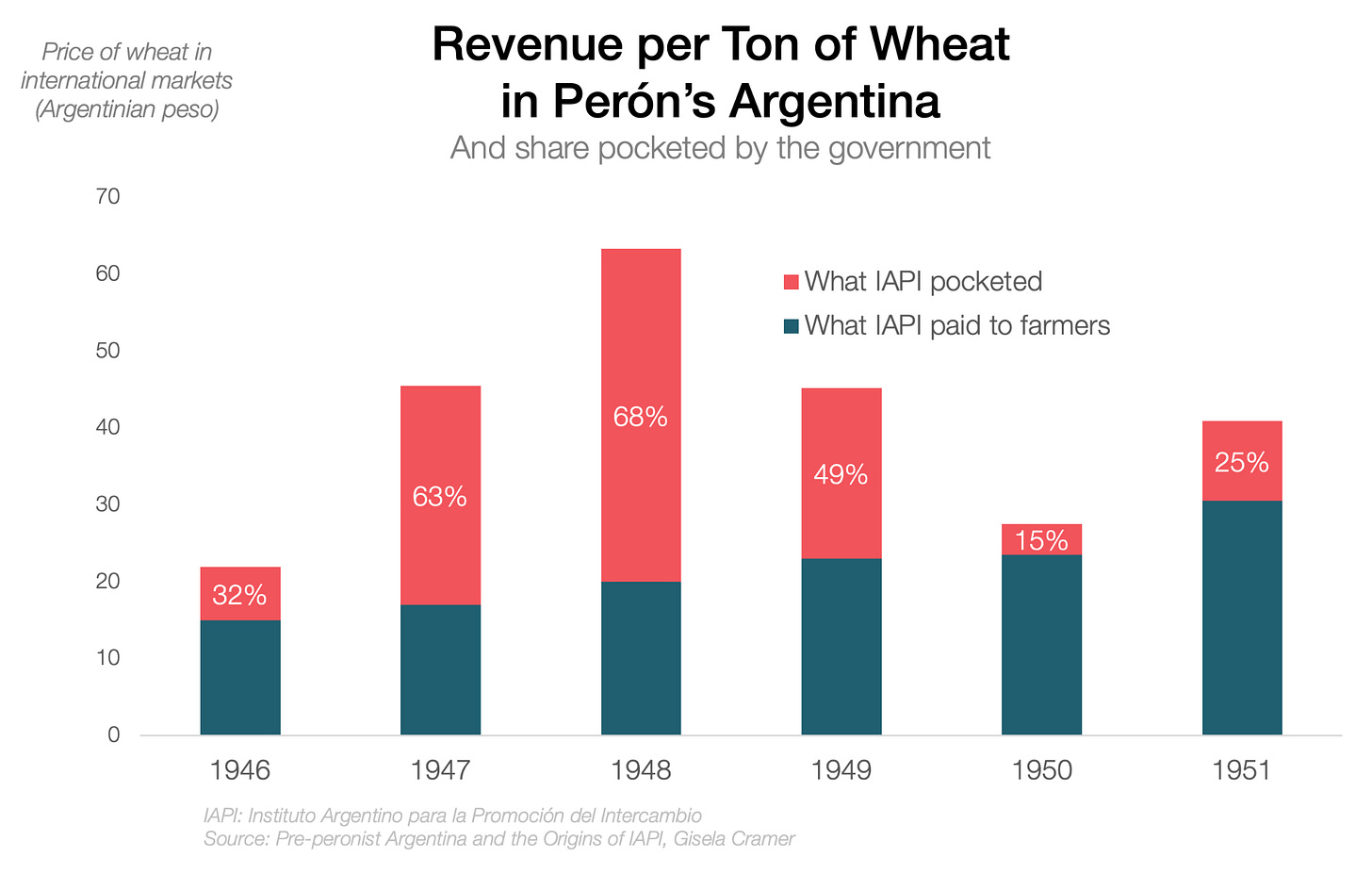

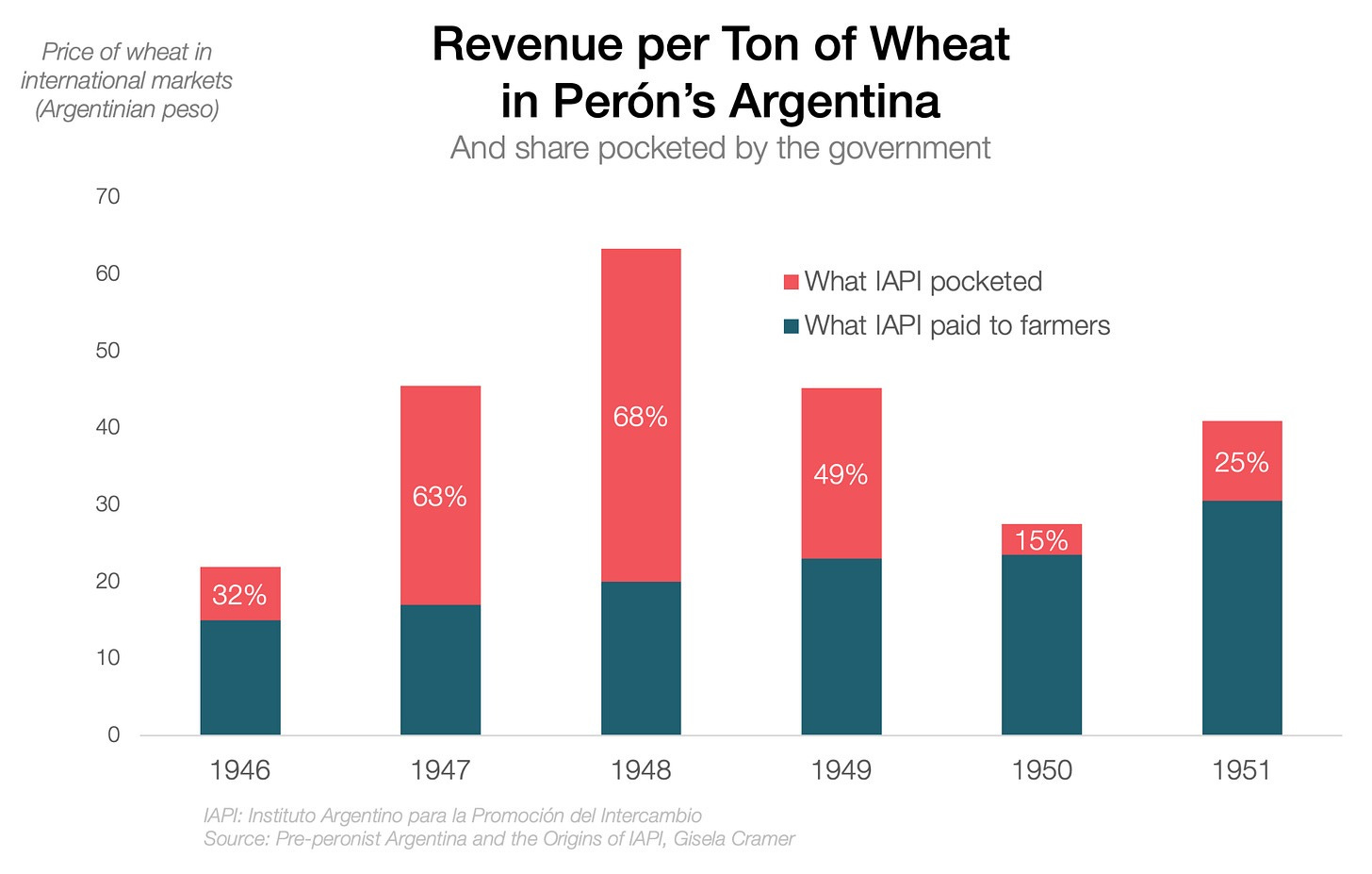

In the 1950s, Argentina’s government bought all Argentinian beef and grain from farmers at a price well below market: up to 60-70% cheaper than world market prices. Then, it sold them in the international markets at a much higher price, which had increased thanks to higher demand after WW2. It pocketed the difference. On average, that was 44% of revenues from wheat between 1946 and 1951, and 40% for corn.

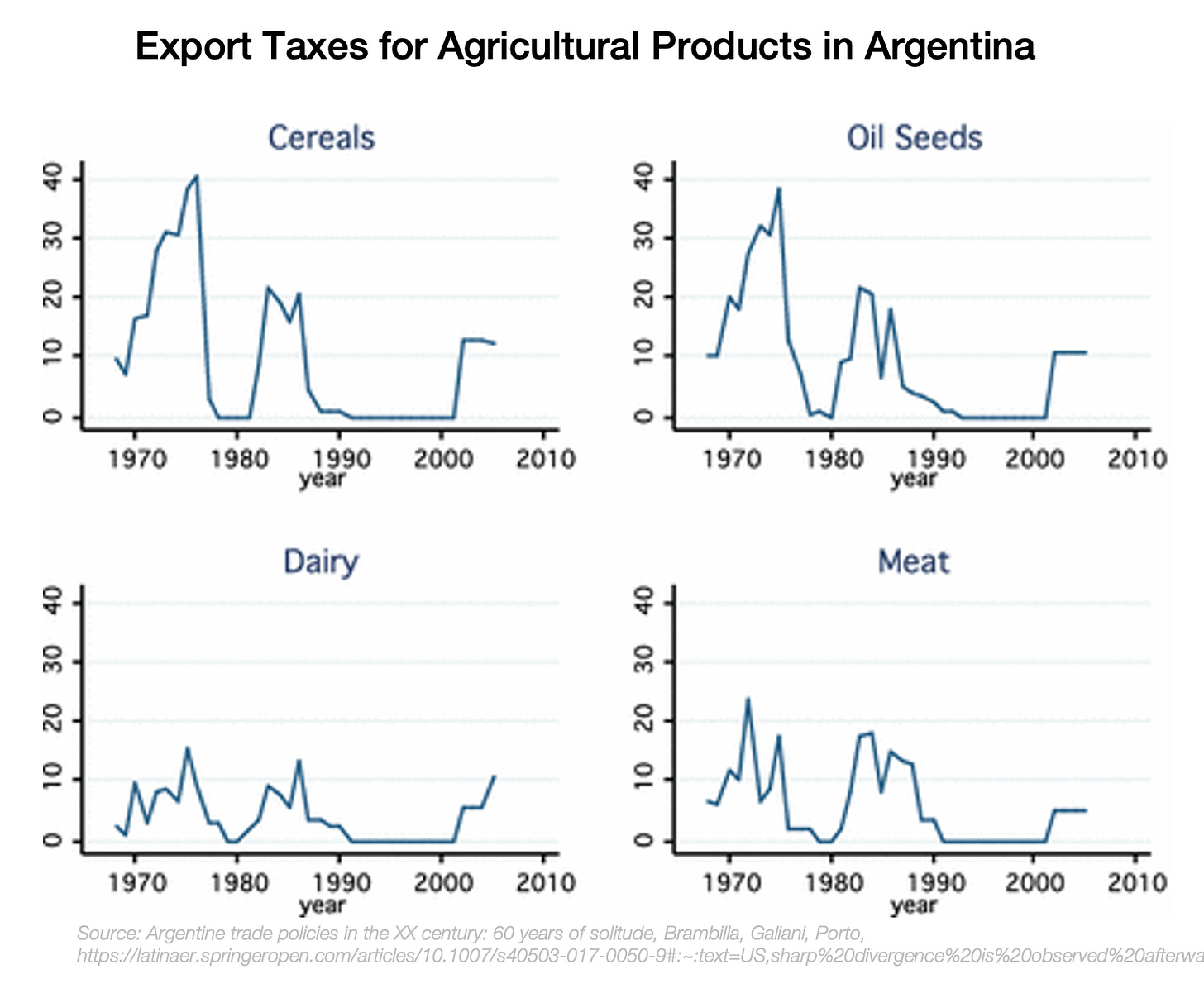

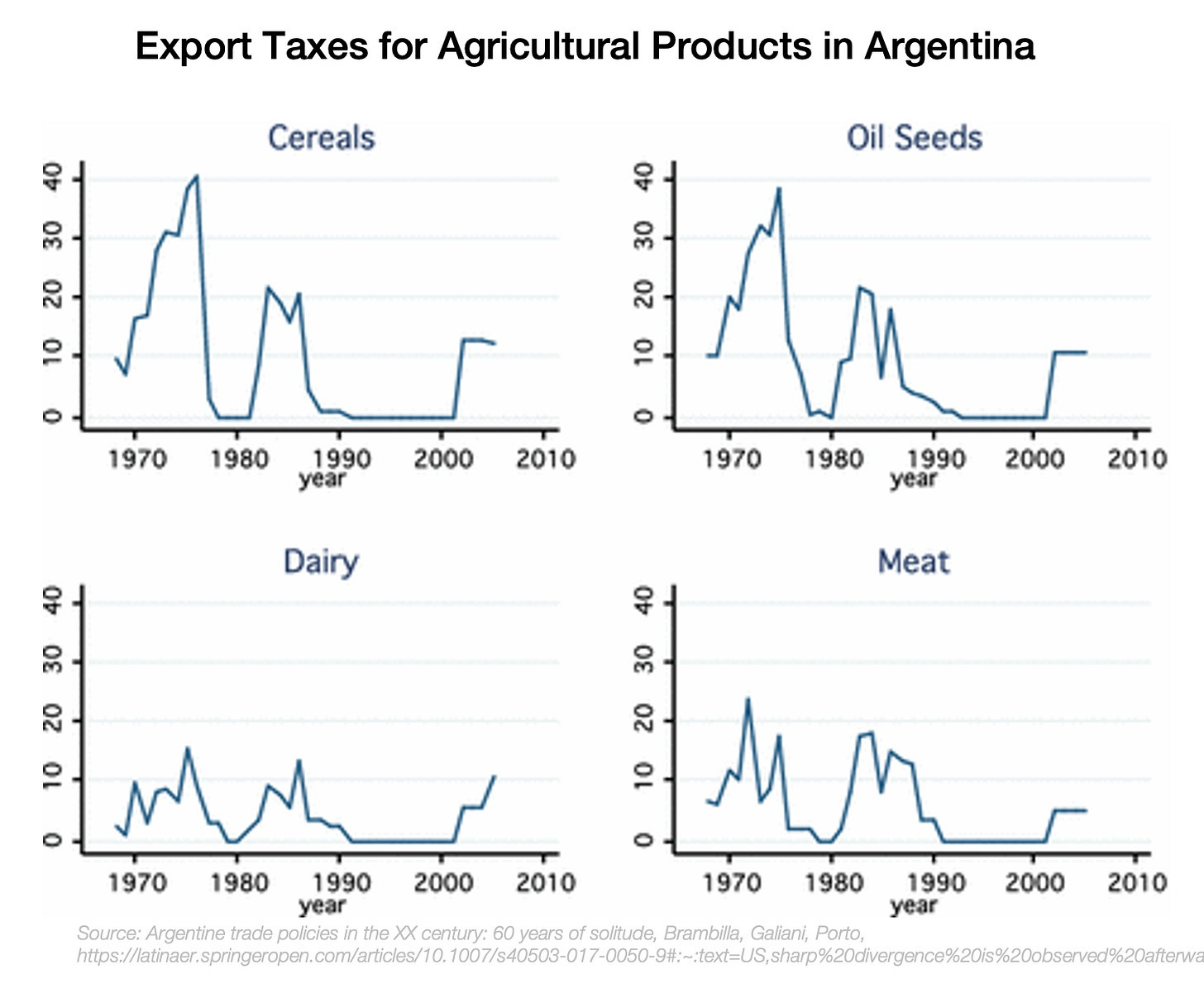

These taxes went down over time, but have been a recurring reality in Argentina’s history.

Heavily taxing exports is much worse than what the Asian Tigers did, because it disincentivizes investment. Imagine that you can produce a ton of wheat at a cost of $80, and you can resell it internationally at a price of $100. This gives you a nice profit of $20, which you can use to reinvest in expanding the business. But if the state taxes you at 30% of revenue, now you can only sell your wheat for $70. Suddenly, your entire operation is unprofitable, and you go bust. Even if your cost was $60, this is bad: You go from a margin of 40% to 14%, so many previous investments become unviable.

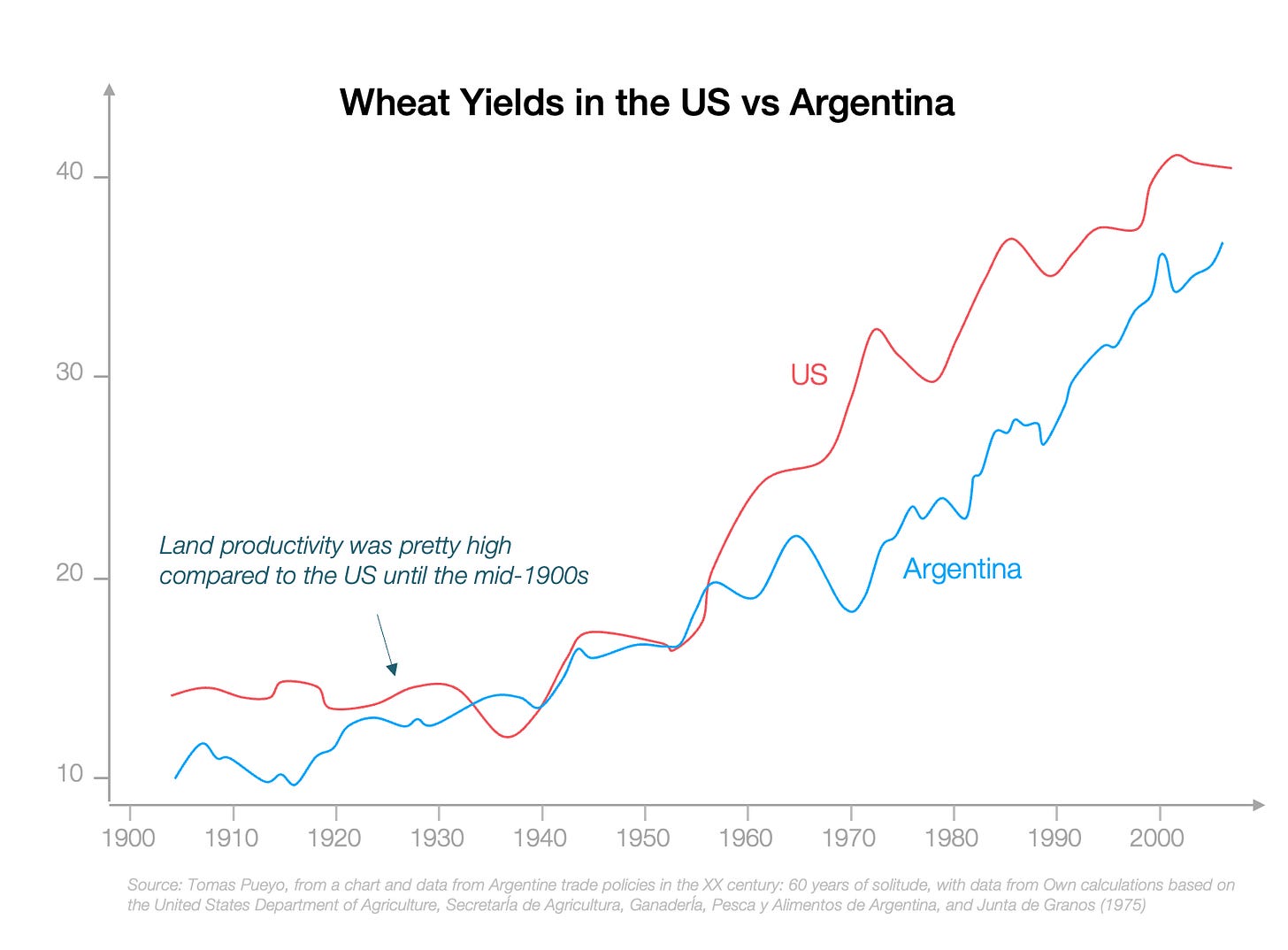

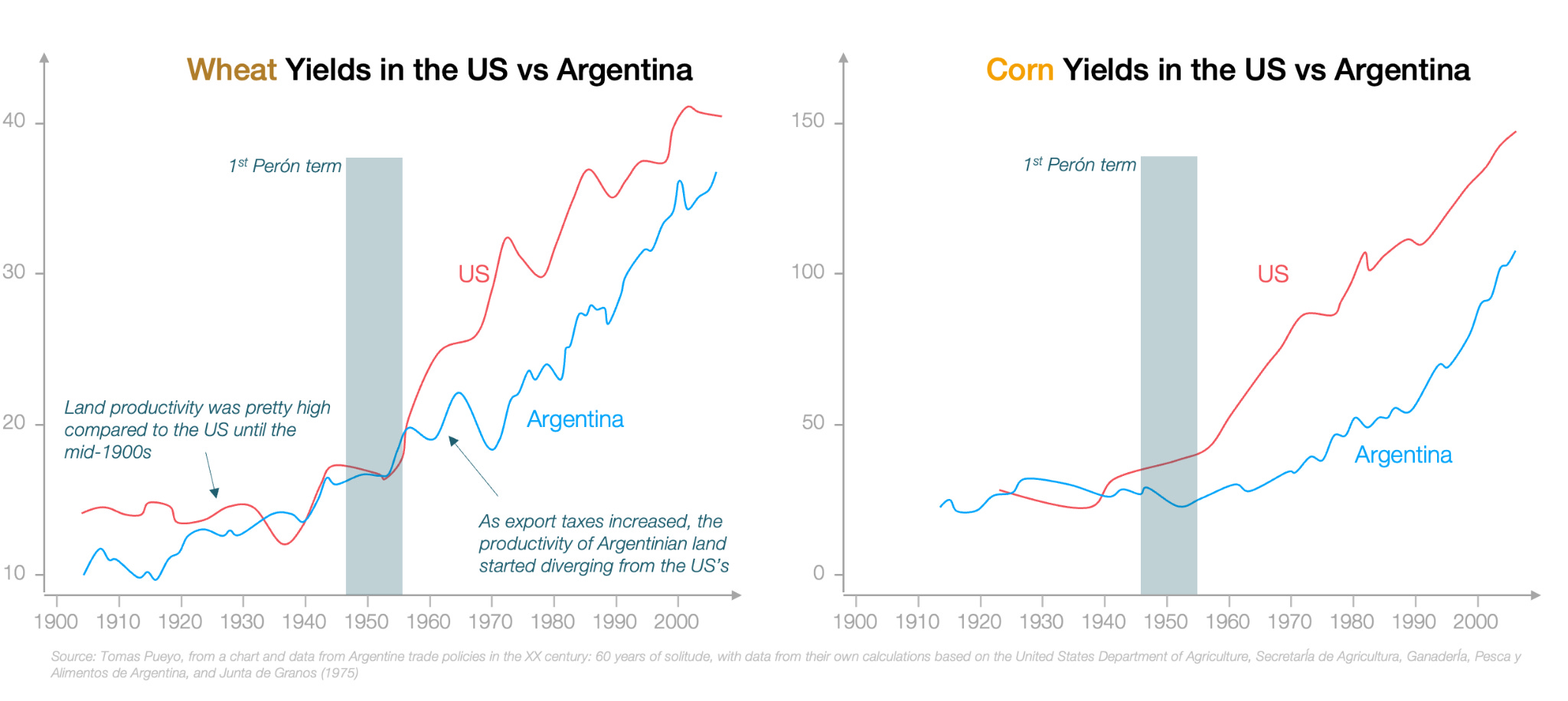

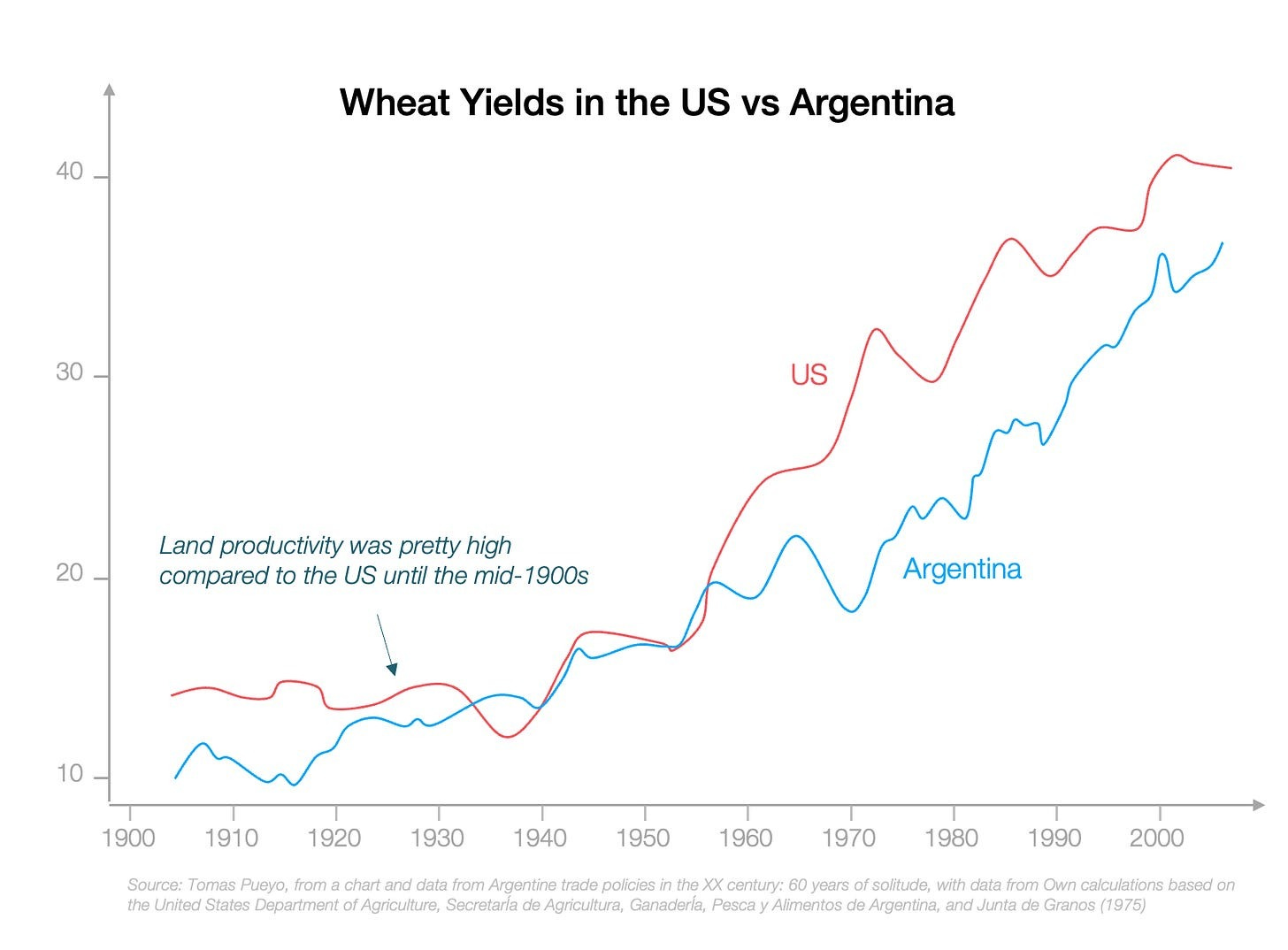

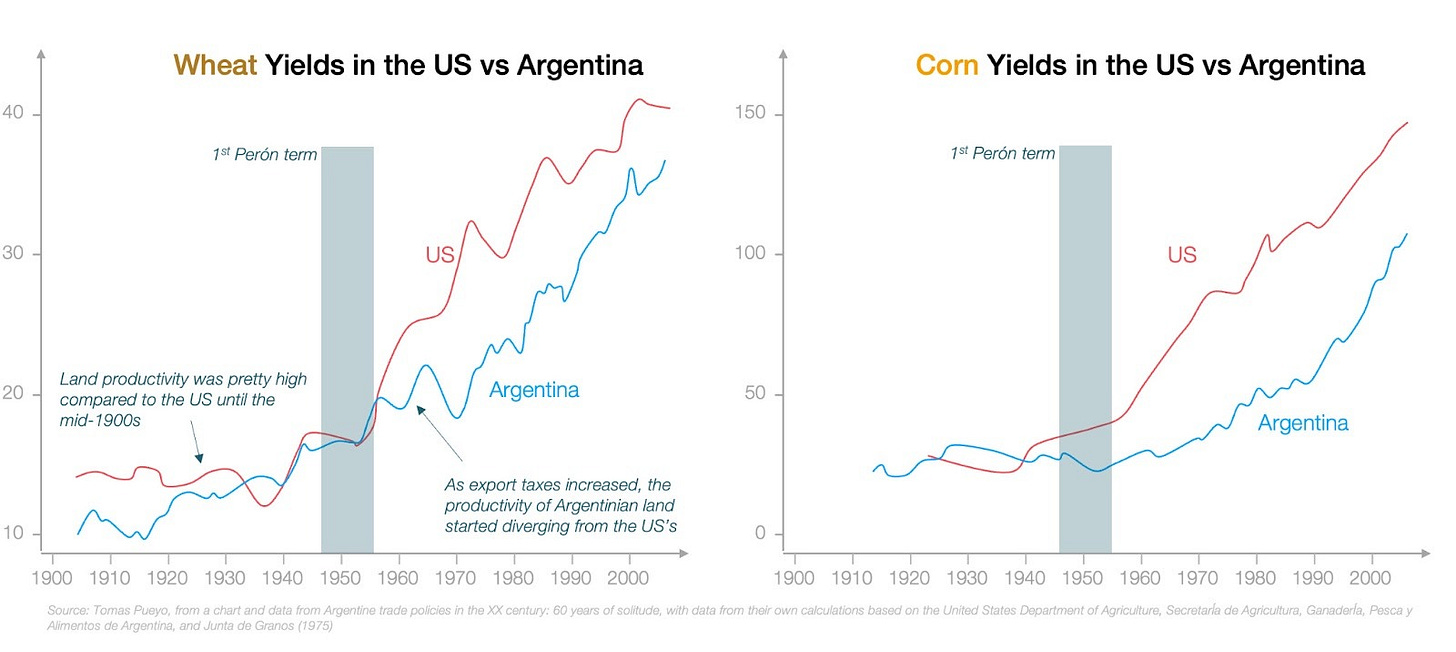

This reduces both production (and so exports), and investment. Indeed, Argentinian agriculture suffered from this, which we can see in the graph of wheat & corn productivity from before the export tax was introduced during Peron’s first term, when yields were still competitive:

2. Industry

How many Japanese, Taiwanese, and South Korean industrial brands do you know?

How many Argentinian ones?

Yep. The Asian Tigers succeeded where Argentina failed. Why?

Recall how the Asian Tigers protected their infant industries with cheap loans, low taxes, import taxes against the competition, etc? Argentina did something similar, import substitution. But with some crucial differences that changed the outcome entirely.

Argentina made a lot of money through agriculture, but only in booming international markets. During the world wars and the Great Depression of 1929, demand crashed, and with it commodity prices and Argentinian incomes. Without foreign currency, the country couldn’t afford imports anymore during these hard times, which meant no more manufactured goods. So it concluded it had to produce stuff by itself—substitute imports with local industry.

Notice the subtle difference here, though: This was not about increasing industrial exports. It was about replacing industrial imports. This changed the mindset completely, from one where local champion companies had to aggressively improve their productivity to compete abroad, to one where local champions were protected from abroad.

Why does this matter? Because exports are impossible to fake. If you win in world markets, it’s because you’re the best. But if you win in local markets… You’re simply good at getting Daddy State to protect you and your lack of productivity against internal and external competitors. The Argentinian state used:

Import barriers, such as tariffs or quotas against international competitors

Cheap loans to local industrial companies

Different exchange rates for agricultural exports and industrial imports, so that industries could buy at a discount

State-owned companies

Subsidies, such as below-cost electricity or train transportation

Tax exemptions

All of these tools were similar to those used by the Asian Tigers. The difference was how they were used.

Export Discipline

This is by far the most important difference. These aids were not conditional on winning in global markets like in Asia, so most of these companies simply stayed in the local Argentinian market, protected from competition. They kept prices high, and lived off the rents.

Meanwhile, the rest of the country had to pony up more cash to buy the same appliances that would be better and cheaper from abroad. Terrible.

Economies of Scale

Export discipline has another advantage, which is that an exporting company has a huge potential market. This is especially important if there is a high upfront cost. Imagine you want to make steel. You need a massive factory to do it, so you better have a market that can buy millions of tons to amortize the upfront cost. If your market is small—like the Argentinian market—you will never have enough customers for economies of scale, and your costs will always be too high.

Car factory costs in Argentina, Brazil, and Mexico were about 60% to 150% higher than in the United States.—Import Substitution in Latin America, Baer

The paper industry (excluding newsprint) had 292 plants of which only 25 had a capacity of 100 tons daily, which is considered the minimum economic size. In the chemical industry, too, there are a great many instances in which there is a wide gap between the plant sizes most frequently found in the region and the sizes constructed in the industrialized countries.—Import Substitution in Latin America, Baer

Spray and Pray

Each time you give a cheap loan, subsidize a cost, or increase some import tariff, it costs the state money. They’re like a tax on everybody else. So the state needs to be extremely thoughtful about it. It can’t prop up local players in every industry, it needs to pick the few key industries it’s going to support, and focus all its resources there.

Usually, this is done in industries that are core for the future of the country. In the case of Japan and South Korea, they both went for steel as a key input to then produce heavy industries such as car companies. Now you know Toyota, Nissan, Mazda, Subaru, Hyundai, Kia… But you might not know the powerful Nippon Steel or the South Korean Hyundai Steel4 or POSCO.

Within the industries Argentina decided to play, it should have found the winners and supported only those, pushing the others to die or merge. It’s easier to support one big company than a bunch of small ones. For example, Argentina had over a dozen car companies,5 which is good to start but you need them to merge!

In Argentina, excessive diversification, unused capacity, large inventories because of import controls, and difficulties in obtaining outside finance explain the high price level in the heavy electrical equipment industry.——Import Substitution in Latin America, Baer.

Comparative Advantage

It’s not enough to pick a few industries. The focus should be on only the ones where Argentina had a competitive advantage. You can’t be good at everything. Pick your battles. For example, given its agricultural might, could it have pushed for agricultural manufacturing companies? It had Vassalli, Senor, Pauny, Zanello, and Araus.6 Could it have produced the Argentinian John Deere with more support?

What other industries could Argentina have picked? Meat-packing and cold-storage processing? Railways? Shipbuilding? Metallurgy, nuclear, precision instruments?

Instead, it supported electronics companies like BGH, Newsan, SIAM, or Philco. But electronics is a very low-margin industry in which Argentina has no competitive advantage and you need exports to reach sufficient scale to bring down costs. As is, Argentinians had to spend much more to get their worse TVs, and in the process spend up to 1% of GDP subsidizing the industry!7 Another example is textiles and apparel. Do you really want to compete with the Indias and Bangladeshes of the world and their rock-bottom wages and no margins?

High Compensation

Speaking of wages, the Asian Tigers kept wages low for a long time to keep overall production costs low. They did so, among other things, by working with trade unions, who understood that they needed a long period of low wages to become competitive, and only then could they increase wages.

Argentinians held the opposite view. They grew up experiencing high inequality from agricultural exports, so they wanted to tax them to redistribute wealth to the people. Industrial production (and exports, when they existed) were seen as yet another source of money to tax. The exact opposite mindset as in Asia, with resulting higher wages, higher costs, less competitiveness, and a lack of global champions.

Employers were forced to improve working conditions and to provide severance pay and accident compensation, the conditions under which workers could be dismissed were restricted, a system of labour courts to handle the grievances of workers was established, the working day was reduced in various industries, and paid holidays/vacations were generalised to the entire workforce. Perón also passed a law providing minimum wages, maximum hours and vacations for rural workers, Sunday rest, paid vacations, froze rural rents, presided over a large increase in rural wages, and helped lumber, wine, sugar and migrant workers organize themselves. Perón established two new institutions that increased wages: the “aguinaldo” (a bonus that provided each worker with a lump sum at the end of the year amounting to one-twelfth of the annual wage) and the National Institute of Compensation, which implemented a minimum wage and collected data on living standards, prices, and wages.

From 1943 to 1946, real wages grew by only 4%, but from then to 1948 (under Perón), they grew by 50%.

Subsidies on energy, food, housing, and transport had the same effect of increasing effective compensation.

Let’s take housing: The Perón government built hundreds of thousands of houses. That sounds good, but there are many problems with this:

We can see this as everybody in the country putting money aside to buy a house for a few. Who gets those houses? Friends of politicians? Are the recipients the most deserving? Those who need the houses the most?

Where does this money come from? If it’s not a sustainable source (hint: agricultural booms and busts are not), it’s a recipe for disaster.

The cost of building additional housing goes up (since the government is now outbidding the private market for builders), making it harder for everybody else to get a home. When you want everybody to get a home, the first thing you should do is focus on lowering all types of building costs.

All these things (housing, holidays, retirement…) are great objectives for a country to have, but it was too early to have so many. Employees can only earn as much as they produce. When they are not very productive (that is, early on in a country’s path to development), what these measures achieve is increased costs for industries, to the point where they become uncompetitive and either disappear or must be subsidized by the government—that is, the government taxes the productive parts of the economy (here, agriculture) to subsidize high standards of living for industrial workers, who are not productive enough to pay for themselves.

Trade Unions

How did Argentina get to such a problematic situation where wages outpaced productivity? One key factor is trade unions. About 40% of legal workers are unionized in Argentina, and these unions have outsized power.

In general, I think the best way to improve the position of workers is full employment, as competition between employers will drive up worker conditions. However, sometimes this process is not optimal, and trade unions can help balance power between workers and employers. But the key there is balance.8

There was not enough balance in trade unions in the US in the mid-20th Century, which was the main cause of the deindustrialization of the Rust Belt: Industries left for the South, much less unionized, and with cheaper costs. Something along those lines happened in Argentina.

But where did the power of Argentinian trade unions come from? Before taking power, Perón was the Secretary of Labor. There, he allied with trade unions. It’s thanks to them that he rose to power. Since his power base came from trade unions, he took care of them, and they took care of him. The most obvious way lies in the concept of Personería Gremial: Each industrial sector only has one legal union! And they’re all under the purview of one union, CGT! Can you imagine the level of power CGT has?9 Then, Perón made collective bargaining universal and state-enforceable.

Of course, such power concentration translated into political power and a revolving door between politics and unions that led to corruption.

As of today, Argentina still has stricter employment protection legislation than other Latin American countries.10

None of this happened in the Asian Tigers. South Korea and Taiwan were the most radical (they both fought Communists in their respective civil wars) , and their government controlled unions, which had limited power. Unions also existed in Japan, but under government supervision. A crucial fact is that trade unions were much less centralized. For example, in Japan, each company has its trade union. This means two things:

Unions are much weaker, but strong enough to face the employer

They’re tied to the future of the company, so they’re very interested in the company succeeding and don’t care about country-wide economic development.

Lower Agriculture Productivity

The high cost and low value of local agricultural machinery was especially hurtful to Argentina’s golden goose—agriculture. If farmers had been able to buy international machines, they could have increased their productivity massively, which would have resulted in more exports and wealth for the country. But import substitution made it impossible.

Back-Integration Resistance

Asian countries supported fundamental industries like steel. This matters because once you are competitive in something like steel, you have a competitive advantage in integrating vertically—building stuff down the line more cheaply, like cars. It takes time and effort, but the Asian Tigers did it by inviting foreign companies into their countries and making sure there was technological transfer between foreigners and locals.

Argentina frequently supported import substitution for consumer goods. Here, the incentives are the opposite, because if you’re producing consumer goods, you’re probably importing lots of machinery and materials from abroad. If you start making these machines and materials yourself, you’re likely going to make them worse and more expensively, which is going to make your consumer goods crappier. So firms pressured the government to avoid developing domestic intermediates.

If the government had pushed, maybe Argentina could have integrated vertically, but it didn’t, and the country didn’t capture entire value chains.

As you can see, this is quite a damning list of differences. No wonder Argentina has no global industrial or consumer champions!

3. Financial & Fiscal Management

That already sounds like a lot of mistakes. But we’re not done! It’s time to talk about the financial and fiscal ones.

Lost Land Productivity

Remember how we talked about the export taxes on grains and beef? This might be good or bad, depending on how they used the money. The downside of such high taxes is that farmers might underinvest: There is less surplus to buy more land, fertilize it better, acquire more machinery, build better irrigation systems… Returns on investment are lower. So taxation like this reduces long-term production.

Asian Tigers frequently intervened in the international sale of their countries’ crops, but they also reinvested a lot of that money in the agricultural sector, so crop production in the long term improved. In fact, these countries might have better funded their agriculture with these taxes than without, as this forced investments in farms that farmers might have preferred to save or invest elsewhere.

This is not what Argentina did, though. From what I can tell, it did invest some money to support agriculture, in things like ports and grain elevators, but most of the money didn’t flow back into agriculture. That’s probably another reason why farm productivity started diverging in Argentina vs the US.

Low Return on Investment

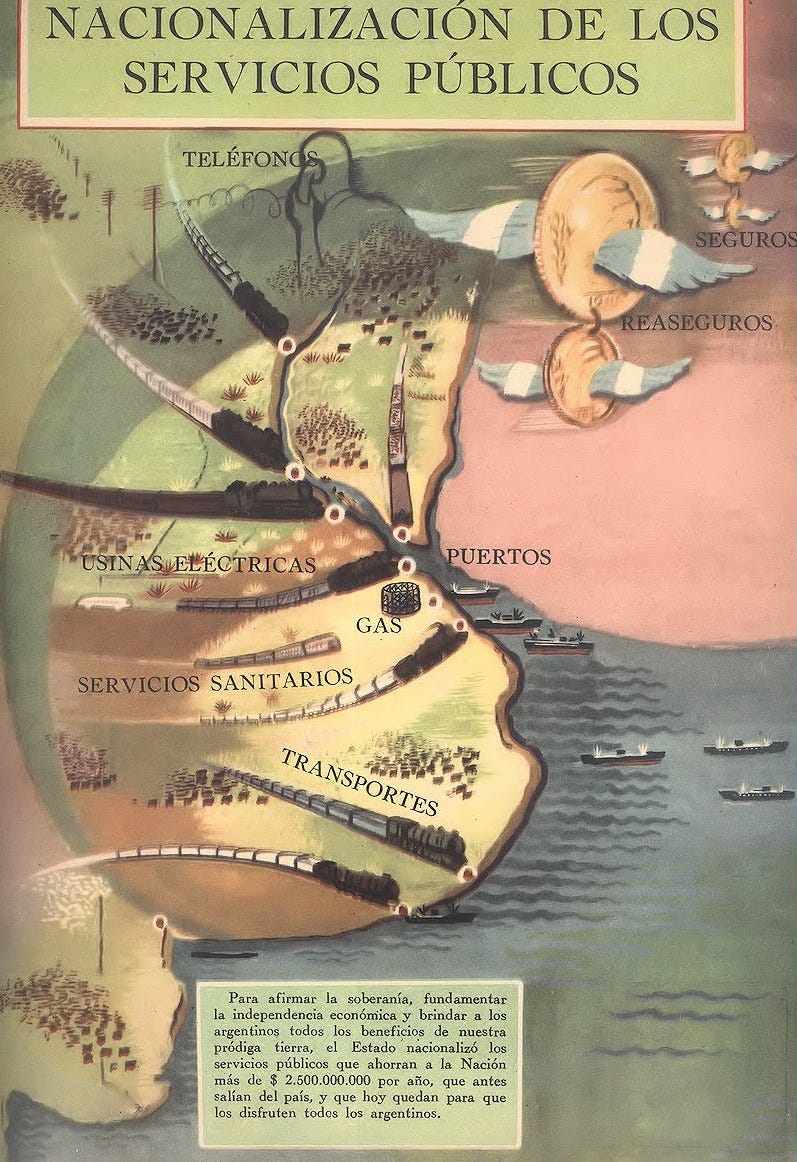

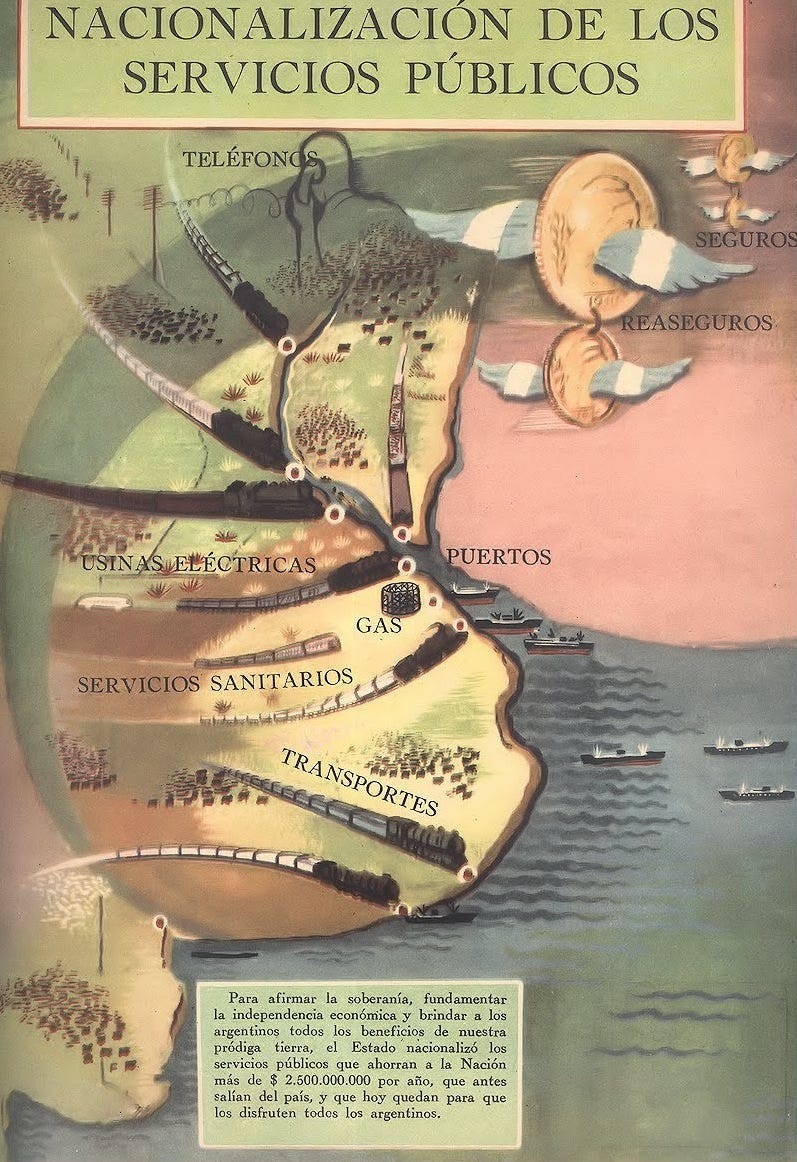

So how did Argentina’s state spend that surplus? Among other things, it invested in the country:

It paid the national debt

It nationalized the entire banking system, including the central bank (which was previously controlled by the UK)

It nationalized the railroads

It created a merchant fleet

Public works expanded access to potable water and sanitation

It invested in coal and petroleum exploration, built the first gas pipeline, and developed power plants, hydroelectric dams, and oil refineries.

Some of these were good investments. For example, paying off the national debt allows for future debt. Building energy infrastructure reduces the cost of energy and creates energy exports, both of which are amazing for the country. It’s pretty important to control your own central bank.

Others are dangerous. If you nationalize most of the banking system, you:

Eliminate the insights from bankers on the ground

Lose the incentive to find the best places to allocate your money

Both of which lead to lower return on capital.

It’s not just the financing that might be problematic, but also its magnitude. During the first Peronist terms in the 1940s and 50s, the Industrial Credit Bank financed 52% of all industrial activity, with peaks of up to 78% in 1949! This is way too much money, too concentrated in the government, which leads to waste and corruption.

South Korea and Taiwan also nationalized the banking system, but they were able to keep a good financial allocation because the government was less corrupt and more technocratic. Argentina was too prone to populism and corruption, and its banking system was not as efficient. Many loans went to political allies rather than to strategic and efficient industrial champions.

Foreign Direct Investment

Taking over foreigners’ investments in your country is a fantastic way to make sure they don’t invest anymore.

Since Argentina grew during the UK’s apogee, most of its foreign investments came from the richest country at the time, the UK: its railroads, maritime trade, banks… This financing was crucial for Argentina’s development, but it had its downsides. For example, Argentina had a nascent wool and clothing industry in the 1800s, but when the British arrived and financed railroads, one of the goals was to reach far inland with their cotton products. The local clothing industry collapsed.

As the UK lost power during the World Wars, it wasn’t in a position to keep financing Argentina. This, coupled with the high share the UK already controlled,11 meant Argentina was not a master of its own financial destiny, which was another factor for populism: Perón accused the UK of imperialism, so when the banking system was nationalized, the goal was not “let’s judiciously invest this money” but “let’s do what we want with this money, independently from what these former imperialists wanted us to do.”

Government Spending

(As opposed to investment)

Remember the high wages we discussed before? This quote is from just after the 2nd Perón term:

In Argentina, the excess of public spending over revenue has for the most part not been used for productive expenditures, but rather for unproductive ones—that is, salaries of public administration employees or the operating deficits of state-owned companies.—Radio announcement of the new economic plan through national radio and television in Argentina after the coup, IADE, from the new Minister of Economy, Martínez de Hoz, April 2nd 1976.

Wages, civil servants, pensions, subsidies… These high costs were one of the biggest sources of public deficit, and not just under Perón. For example, in 2008, the state subsidized 77% of the private pension funds’ beneficiaries. The point of private pensions is very much that citizens are carrying their risk, not the state!

Overspending during Booms

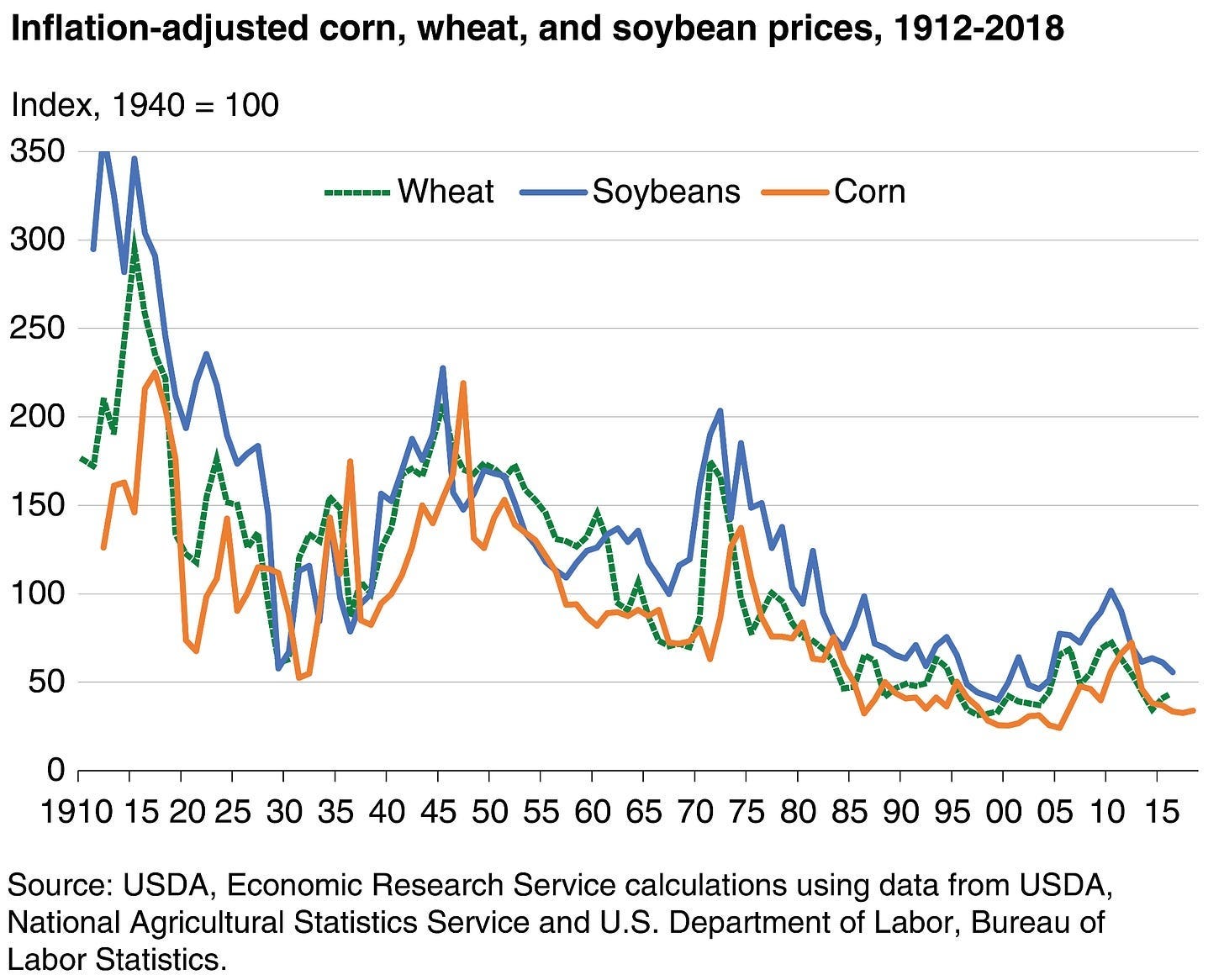

Investing so much money from boom times also causes a problem of timing.

Norway is another country that makes a lot of money when international markets are booming, because it sells lots of oil. But it doesn’t let the money from its surpluses flood the economy. It keeps it in a sovereign fund, which invests around the world, and it only uses its real returns to fund the government (about 3% of the fund every year). This completely smooths out government spending across decades,12 so when oil prices tank for a few years, the country barely notices it.

Argentina didn’t do that. Given the massive exposure to commodity exports, and the brutal price swings they have in international markets, Argentina had a huge surplus in bonanza years. It overspent during these booms, as we saw with the huge list of projects Perón undertook.

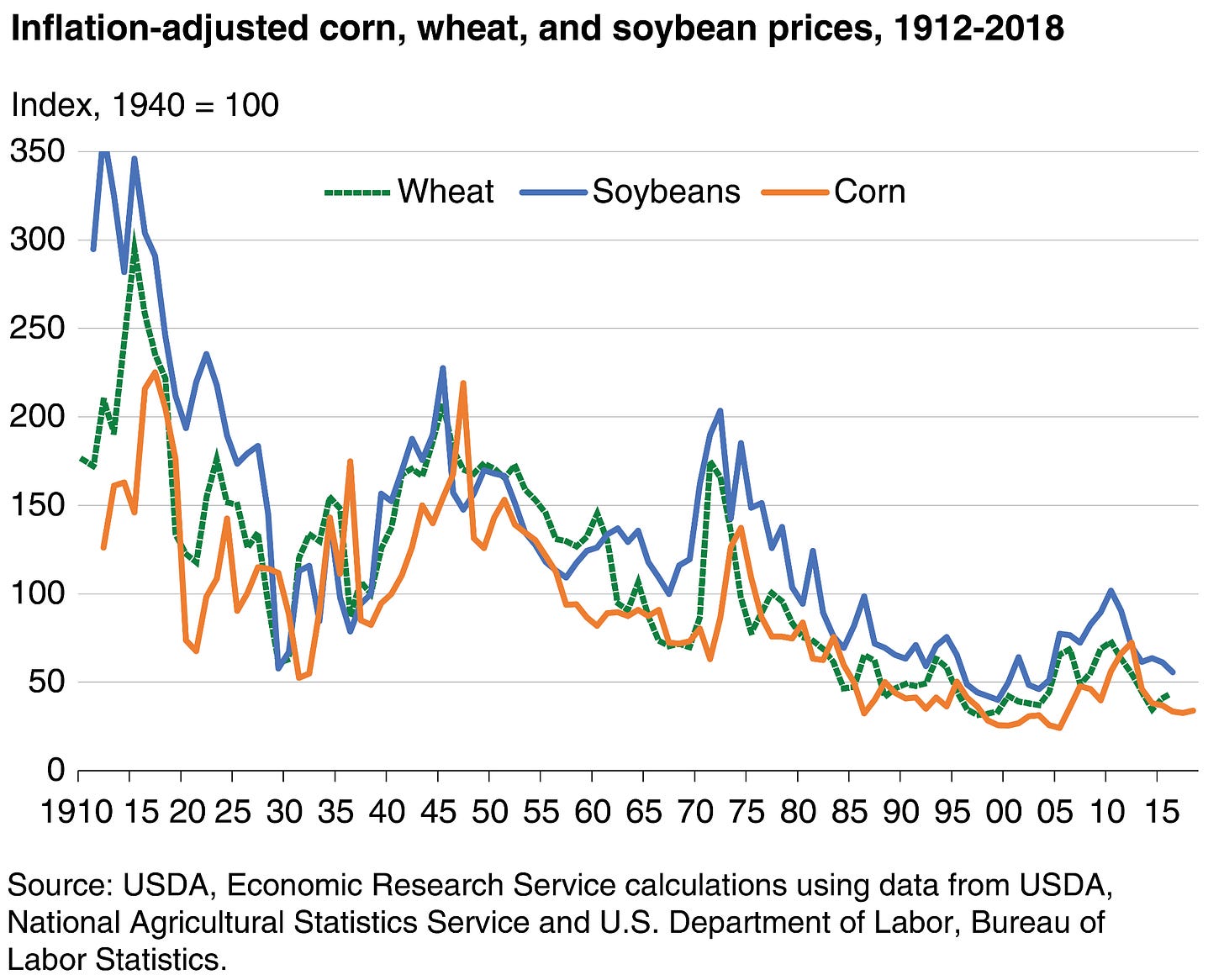

The same thing happened in the last Perón term (1974-1975). Look at the spike in commodity prices:

Between 1972 and 1975, the number of public employees increased by 24% (in the 10 years before that, they increased by 7.4%, so 90% more slowly). This had lots of negative consequences.

One was further lowering the return on investment. For example, if you build houses over 10 years, the flow is steady, builders can predict how much they’ll make, they can invest in the long term, hire employees, increase machinery, and keep prices low. But if all that investment happens in a couple of years, they don’t have time to increase their capacity, so they simply ask for a much higher price. This means less bang for the buck.

Peso Overvaluation

Another consequence of overspending during booms is an overvaluation of the local currency, common in countries that export commodities:13

Exporters in a country sell some commodity in the international market, and make lots of dollars14

The government taxes a big chunk

The government wants to spend this in its country, so it sells the dollars and buys the local currency

This increases the value of the local currency

This makes other types of exports more expensive, so these shrink

The only way out of this is sterilization, which has its own problems.15

Another way to put it is that, during a commodity boom, the government spends much more in the local economy, increasing local prices and salaries. With higher costs, local companies (which compete for the same local resources) are less competitive abroad.

Remember what Asian Tigers did instead? Central banks bought the dollars from exporters and kept them, buying US treasuries and keeping them in their vaults. If they had sold them in international markets to buy local currency, they would have strengthened their local currency. By avoiding that, they allowed industrial exporters to sell for cheap.

Argentina could have chosen to do that, but it didn’t due to its original sin: its agricultural inequality. Wealth redistribution became a political issue, especially since Perón. The government systematically taxed exports and would immediately redistribute the proceeds through the high wages we discussed earlier, plus other ways of injecting cash into the economy (pension increases, civil servants…).

Inflation

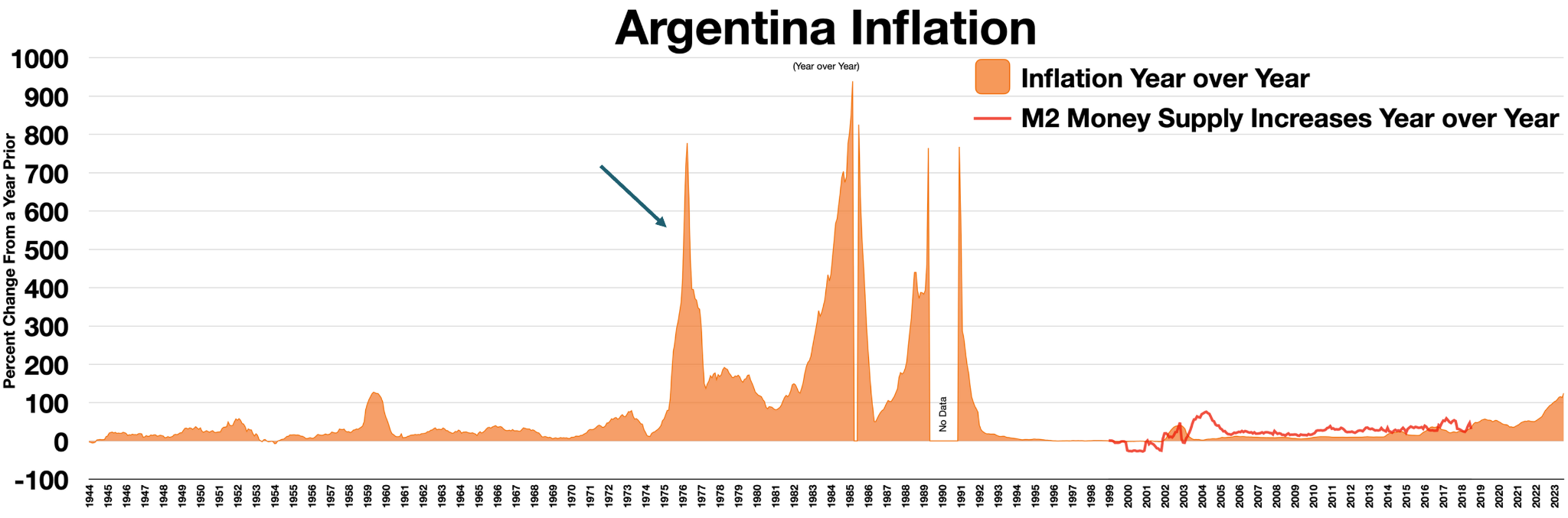

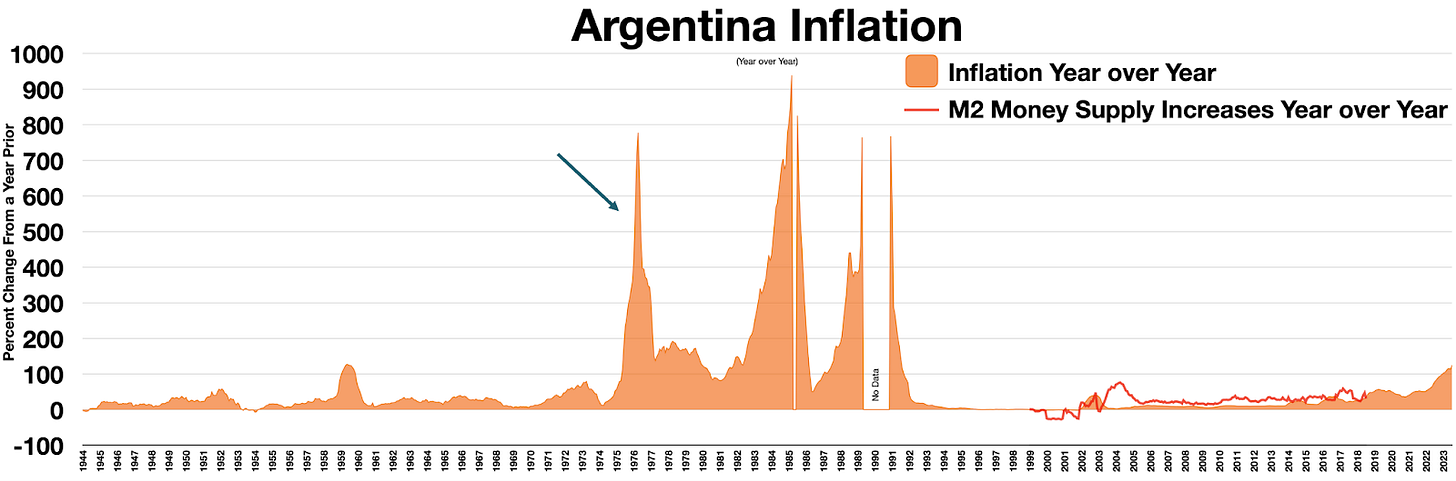

The overvaluing of the peso during boom times is also one of the sources of Argentina’s famous inflation cycles. Remember there was an increase in commodity prices in the early 1970s? Look at Argentinian inflation just after that:

Why the inflation spike?

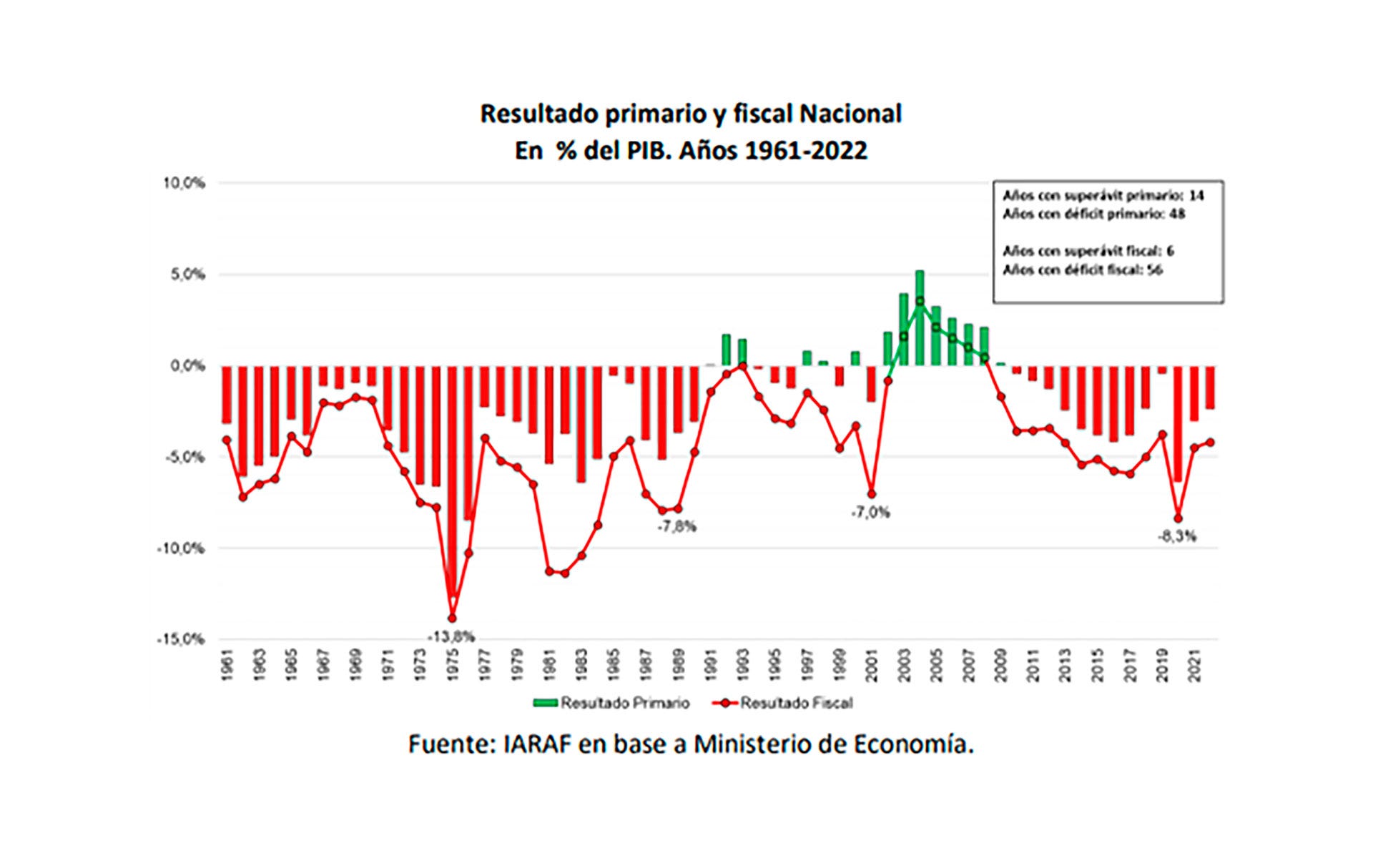

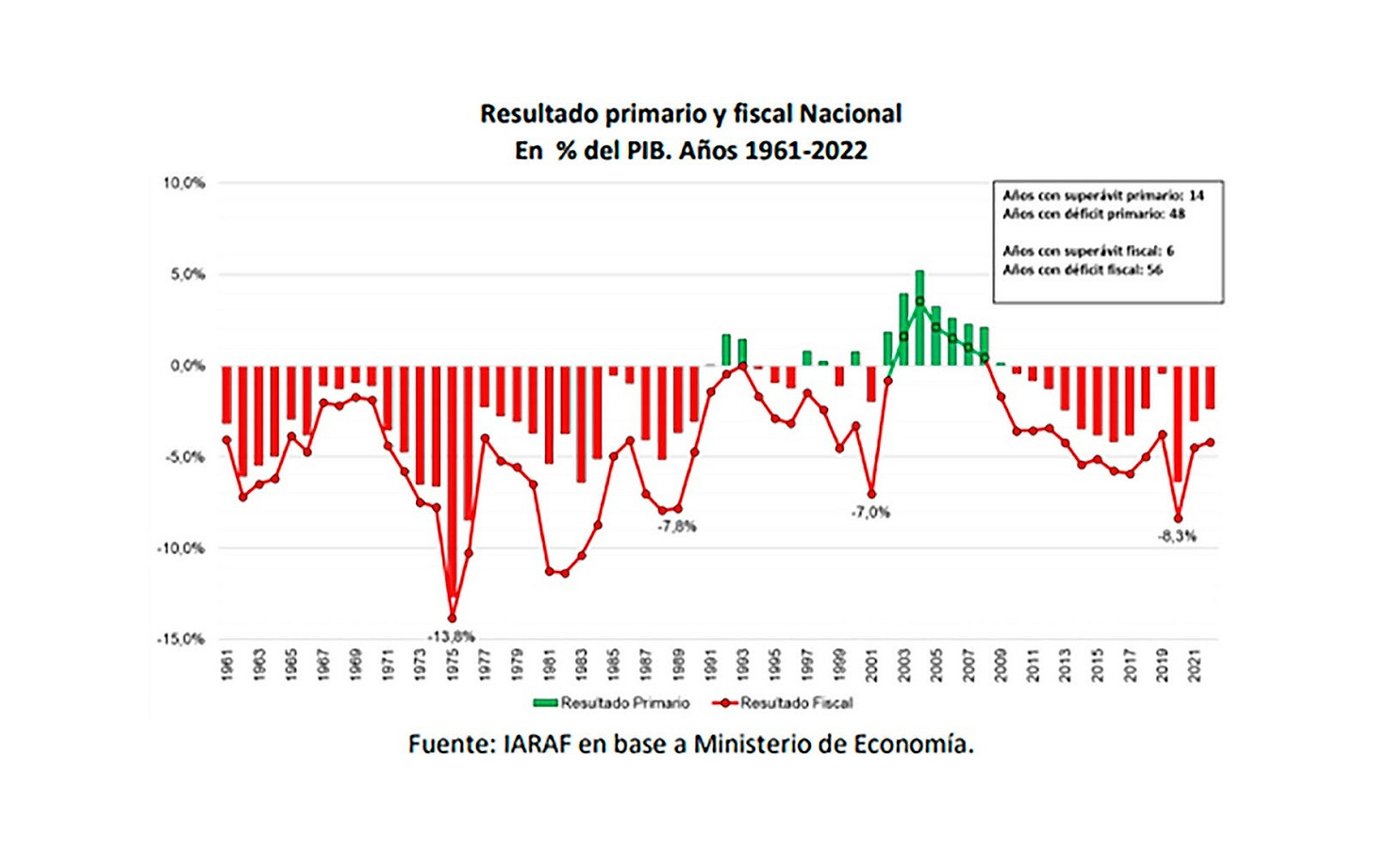

This is the government deficit. It grew from 1970 onwards, peaking in 1975 at nearly 14% of GDP. At that point, taxes only covered 20% of government spending! The government covered the remaining 80% by printing money and raking in debt, which led to inflation.

But why was there such a deficit in the first place? Because of the increased spend we mentioned before: more civil servants, higher wages, subsidies, more investment… So if we summarize this inflation cycle:

Commodity prices go up

Agricultural exports boom

Government income booms

Government overspends

Commodity boom ends

Government overspending is not covered by export taxes

Print money to cover government overspending

Inflation

Later cycles were not all led by booms of agricultural exports, but by some of the consequences of previous cycles. For example, in the late 1980s:

Argentina had a huge deficit and couldn’t cover it with new debt

So it printed a lot of money (over 40x increase in base money in a year!)

Why the huge deficit?

Because it had been running deficits for a long time

So it accumulated a huge debt

interest payments on that debt accumulated, worsening the deficit

Why couldn’t Argentina cover deficits with new debt?

Huge debt, as described

International markets were not accessible, as Argentina had defaulted on its debt in 1982, because it was so high back then.

A mix of both of these happened with the Kirchners in the mid-2010s.16

The more often the cycle takes place, the more people learn to expect it, and the harder it is to control:

Inflation increases just because people expect it, so they jack up prices

The value of the peso falls because people expect the currency to lose value, so they sell their pesos to buy dollars. This accelerates the process.

How did the Asian Tigers avoid this? Originally, they didn’t have the same luxury problem of agricultural exports that would bring in lots of dollars, so they didn’t have a history of commodity booms like Argentina. That said, government spending never increased as fast as exports, quite the opposite: Asian governments kept dollars in the form of US treasury bills, as discussed. The downside was less social spending in the short term. The upside was more productivity, undervalued local currency, more exports, more wealth accumulation, and more reinvestment in the long term. This reminds me of the fable of the grasshopper and the ant.

Government Defaults

Since its independence, Argentina has defaulted nine times (three times in the 21st Century). You can see how this is a direct result of the actions above.17

Savings

Whereas Asian Tigers forced their citizens to keep their money in local banks to reinvest in industry, this didn’t happen in Argentina, which surrendered that lever too early in its development: It hasn’t pushed Argentinian banks to focus cheap loans into Argentinian industry, and since 1993 lost its big industrial development bank. Its successor is much smaller and less ambitious.

State-Owned Enterprises

There is no justification whatsoever for the State to run sugar, metallurgical, textile, and all kinds of companies under the pretext of maintaining sources of employment.—Radio announcement of the new economic plan through national radio and television in Argentina after the coup, IADE, from the new Minister of Economy, Martínez de Hoz, April 2nd 1976.

There’s a role for state-owned enterprises (SOEs). For example, natural monopolies. But states frequently try to control more enterprises than they should: They can bring money and power to the state and politicians, who might use them for their own benefit.

Aside from an opportunity for corruption, SOEs are usually inefficient because the owners are not aiming to maximize profits.

For example, before telephone privatization in 1990:

To get a new line, it was not unusual to wait more than ten years, and apartments with telephone lines carried a big premium in the market versus identical apartments without a line. After privatization the waiting line for a telephone was reduced to less than a week.—Culture and Social Resistance to Reform: A theory about the endogeneity of public beliefs with an application to the case of Argentina, Pernice & Sturzenegger

Also, when SOEs lose money, the government jumps in to fill the gap, rather than letting an unproductive company die and more productive ones take over their resources and the market.

That’s what was happening in Argentina, where in 1976 the government funded all the losses from the railroads, which were bigger than the regional budgets of all regions combined (outside of Buenos Aires).

So Why Is Argentina Poor?

Let’s summarize to see the patterns.

First, Argentina’s land is extremely fertile. This is great because it generates lots of money for the country, and is why it was rich in the 1890-1930s. But it has a few downsides:

It requires delicate currency management, to avoid peso overvaluing and inflation

Since commodity markets swing wildly, the country’s income swings too

Second, probably because of the culture inherited from Spain, but also because of how it gained its independence, Argentina’s land was very concentrated, and it never redistributed it among farm workers. This led to high inequality, and consequently, anger.

This pushed Argentinian politicians to find another way to redistribute agricultural wealth: not through land, but financially, by controlling and taxing agricultural exports. Unfortunately, this meant that the huge swings in international commodity markets became swings in government income.

The combination of these two is extremely problematic: The first one (no land redistribution) begets financial redistribution to reduce inequality (or else you get conflict), but it’s hard to redistribute in a way that follows swings in international markets, so instead redistribution was so generous it was wasteful during boom times, and it led the government to huge budget holes in bust times.

The waste during boom times can be seen in the massive worker compensation increases that happened then, the huge social support system, the overfinancing of industries, the nationalizations, the creation of state-owned enterprises…

The holes in bust times led to all sorts of problems like hyperinflation, government defaults, currency devaluation… The economic disarray, in turn, led to political instability, which led to institutional instability.

A third factor to add to the mix is the exposure of Argentina to foreign investors (especially the UK): Since it reached its independence much later than the US and was farther from the UK culturally and geographically, its industrial revolution came much later. By the time the UK was rich (and could invest), Argentina was still an agrarian society, so it couldn’t invest in itself, and most investment came from the UK. This exposed Argentina to foreigners, which bred insecurity and a desire to become self-sufficient. This can be seen in the nationalizations, the taxes to both imports and exports, the policy of import substitution, the overfunding of national industries, the protectionism…

Many of these had a dramatic impact on industry:

Oversubsidized by the government

Protected from foreign competition

Worker compensation too high

Suffered from peso overvaluation and inflation, making costs higher or investment unpredictable

Low access to foreign investment and tech

Competition from state-owned enterprises

Low economies of scale

Corruption

That’s why Argentina’s industrial base is so much weaker than it could be

All of these mistakes highlight how amazing the work of the Asian Tigers has been. But also how different their conditions were: All three Tigers emerged from mid-20th Century wars with strong anti-Communist governments and dirt poor societies that only wanted one thing: work to escape poverty. They didn’t suffer from agricultural booms and busts, and didn’t have a bias against international trade. Argentina didn’t go through any of that. Its experience was one of wealth and inequality.

I think all of this goes a long way explaining why Argentina is poorer today. But it’s not all. The country has weak institutions, corruption, and a history of coups and dictatorships that can’t be fully explained by the economics. We’re going to look into that next, as well as:

How Milei and his measures fit into all of this

What I’d do differently if I were him

Thanks to Pablo Pérez de Rosso, Jorge Hintze, Shoni Bruell, and Heidi Hughes Linehan for revisions to this article and to Franco Bassi for the Spanish translation.

¿Por qué es pobre Argentina?

La raíz de su mala gestión económica

El partido de Javier Milei acaba de ganar las elecciones legislativas en Argentina. ¿Por qué? ¿Cómo podemos entender sus políticas? ¿Llevarán a Argentina de regreso a la riqueza y la grandeza? ¿O la empujarán de nuevo a otro ciclo de caos? ¿Debería Milei hacer algo diferente? Para responder a estas preguntas, necesitamos entender por qué Argentina es pobre hoy.

Pero hacerlo es una de las tareas más difíciles de la economía. El mal desempeño de Argentina es uno de los temas más debatidos en la economía internacional. Así que he intentado sintetizar lo que nos dice la investigación, y descubrí que una forma esclarecedora de hacerlo fue comparar el desarrollo de Argentina con el de Japón, Taiwán, Corea del Sur y China (se abordó aquí), porque todos estos países hicieron cosas muy similares pero terminaron con resultados dramáticamente distintos. Esto nos va a ayudar a aislar las pocas diferencias que probablemente causaron la caída de Argentina. En cualquier caso, este es un tema tan complejo que estoy seguro de haber cometido errores. Si encuentras alguno, por favor corrígeme en los comentarios.

Hacia 1900, Argentina era 2 veces más rica que Japón, y por encima de 4 veces más rica que Taiwán, Corea del Sur y China. Pero hoy todos estos países son más ricos que Argentina. ¿Por qué?

Esta es una historia mucho más interesante de lo que parece, porque las similitudes entre las políticas económicas de estos países son asombrosas. Pero hay unas pocas diferencias cruciales que hicieron que los países asiáticos crecieran mientras Argentina se estancaba. Así que primero veremos qué hicieron los asiáticos y luego compararemos con Argentina para ver dónde salió todo mal y por qué.

Cómo se desarrollaron los Tigres Asiáticos

Lo expliqué en detalle aquí, pero este es el resumen.

1. Agricultura

La tierra en Taiwán, Japón y Corea del Sur estaba concentrada en pocas manos. Lo primero que hicieron después de la Segunda Guerra Mundial18 fue redistribuirla. Esto dio trabajo a mucha gente y aumentó la productividad agrícola, porque los agricultores ahora eran dueños de la tierra y de sus productos, así que intentaron mejorar ambos: invirtieron en maquinaria, mejor fertilizante, mejor grano, no sobreexplotaron la tierra…

A medida que aumentaba la productividad agrícola, estos agricultores podían ahorrar dinero. La productividad creció lo suficiente como para alimentar al país. Los gobiernos aplicaban impuestos a los agricultores, pero también los subsidiaban con frecuencia mediante precios mínimos para sus cultivos, ayuda para obtener fertilizantes, semillas… Había poca exportación de alimentos, pero lo que existía estaba fuertemente controlado y gravado.

Gracias a esto, cada país desarrolló una amplia base de agricultores, incrementó su ahorro y obtuvo ingresos en moneda extranjera.

2. Industria

Una vez que la agricultura funcionaba, estos países empezaron a redirigir el excedente hacia las industrias para desarrollarlas. Eligieron unas pocas industrias clave y las apoyaron de muchas maneras:

A menudo aplicaban aranceles a las importaciones que competían con las industrias protegidas. Esto se llama proteccionismo de industrias nacientes.

Redujeron sus impuestos.

Les dieron préstamos baratos.

Les concedieron licencias de importación para que pudieran importar y hacerlo con impuestos limitados.

Crucialmente, solo hicieron esto con las empresas que crecían rápido y eran capaces de competir internacionalmente. Aquellas que no podían competir dejaron de recibir préstamos baratos y fueron empujadas a fusionarse o quebrar.

3. Finanzas

¿De dónde salía el dinero para estos préstamos baratos? De los agricultores (y otros ciudadanos), que no podían invertir su dinero donde quisieran. Los mercados inmobiliarios y la bolsa no eran accesibles para ellos, y tampoco podían colocar su dinero libremente en el extranjero. Se les obligaba a poner el dinero en el banco con intereses bajos. Ese era el dinero que luego se prestaba a las empresas industriales.

Además, el tipo de cambio se mantenía bajo y la inflación se eliminaba:

Las exportaciones quedaban exentas de impuestos, por lo que había muchas exportaciones. Estas traían moneda extranjera a sus países (normalmente dólares). Parte se gastaba en mercados internacionales (fertilizantes, semillas, maquinaria…), y el resto se vendía para comprar moneda local.

Los bancos centrales compraban los dólares. Imprimían moneda local para comprarlos.

Esto habría llevado a inflación, así que la esterilizaban emitiendo deuda de bajo interés y obligando a los bancos a comprarla.

La inversión extranjera estaba limitada. Como los extranjeros tienen moneda extranjera y la venden para comprar moneda local, tienden a aumentar el valor de la moneda local. Limitando sus inversiones, limitaban esa apreciación.

El crecimiento de los salarios se mantenía bajo. Se presionaba a los sindicatos para que aceptaran esto. Eso mantenía la inflación a raya.

Cómo se desvió Argentina

1. Agricultura

Vimos en nuestros dos artículos anteriores que la geografía de Argentina es extraordinaria, y el país la aprovechó en su boom agrícola de 1880-1910:

La superficie de tierras cultivadas creció rápidamente

Muchos establecimientos ganaderos fueron reemplazados por cultivos, con la ayuda de una rápida mecanización e inmigración19

Pero aquí está el pecado original de Argentina: las explotaciones agrícolas siguieron altamente concentradas.

Esto no afectó demasiado a la productividad de la tierra al principio, porque los dueños de tierras tenían incentivo para maximizar su producción y, por tanto, sus exportaciones.

Sin embargo, como la propiedad de las tierras estaba tan concentrada, no existía una amplia base de agricultores que pudieran beneficiarse. Unos pocos dueños acumularon un poder económico, social y político desmesurado.20

Esa desigualdad creciente provocó una reacción política que no se produjo en los Tigres Asiáticos. Esa presión política empujó a los gobiernos a aplicar impuestos a la agricultura de una forma mucho menos productiva que en los Tigres Asiáticos.

Los Tigres Asiáticos también aplicaron impuestos a las exportaciones agrícolas, pero eran pocos y usaron la mayor parte de esos ingresos para reinvertir en las granjas. La mayor redistribución del campo a la industria fue indirecta: obligando a los agricultores a ahorrar su riqueza en los bancos, que luego prestaban ese dinero a las industrias.

En cambio, Argentina simplemente aplicó impuestos a las exportaciones agrícolas. Por ejemplo, el IAPI (Instituto Argentino de Promoción del Intercambio) tenía un monopsonio sobre las exportaciones agrícolas (era el único comprador por ley).

En la década de 1950, el gobierno argentino compraba toda la carne y el grano argentinos a los agricultores a un precio muy inferior al de mercado: hasta un 60-70% más barato que los precios mundiales. Luego los vendía en los mercados internacionales a un precio mucho más alto, que había subido gracias a una mayor demanda tras la Segunda Guerra Mundial. Se quedaba con la diferencia. En promedio, eso supuso el 44% de los ingresos del trigo entre 1946 y 1951, y el 40% del maíz.

Estos impuestos bajaron con el tiempo, pero han sido una constante recurrente en la historia argentina.

Aplicar grandes impuestos a las exportaciones es mucho peor que lo que hicieron los Tigres Asiáticos, porque desincentiva la inversión. Imagina que puedes producir una tonelada de trigo a un costo de 80 dólares y revenderla internacionalmente a 100. Eso te da una buena ganancia de 20 dólares, que puedes usar para reinvertir y expandir el negocio. Pero si el Estado te cobra un 30% de los ingresos, ahora solo puedes vender tu trigo por 70 dólares. De golpe, toda tu operación deja de ser rentable y vas a la quiebra. Incluso si tu costo fuera 60 dólares, esto es malo: pasas de un margen del 40% al 14%, por lo que muchas inversiones previas dejan de ser viables.

Esto reduce tanto la producción (y por tanto las exportaciones) como la inversión. En efecto, la agricultura argentina sufrió por esto, como vemos en el gráfico de productividad de trigo y maíz de antes de que se introdujeran los impuestos a la exportación durante el primer mandato de Perón, cuando los rendimientos aún eran competitivos:

2. Industria

¿Cuántas marcas industriales japonesas, taiwanesas y surcoreanas conoces?

¿Cuántas argentinas?

Exacto. Los Tigres Asiáticos triunfaron donde Argentina fracasó. ¿Por qué?

Los Tigres Asiáticos protegieron sus industrias nacientes con préstamos baratos, impuestos bajos, aranceles contra la competencia, etc. Argentina hizo algo similar: sustitución de importaciones. Pero con algunas diferencias cruciales que cambiaron por completo el resultado.

Argentina ganó mucho dinero con la agricultura, pero solo en mercados internacionales en auge. Durante las guerras mundiales y la Gran Depresión de 1929, la demanda se desplomó, y con ella los precios de las materias primas y los ingresos argentinos. Sin moneda extranjera, el país ya no podía permitirse importar durante esos tiempos difíciles, lo que significaba quedarse sin productos manufacturados. Así que concluyó que debía producir esos bienes por sí mismo: sustituir importaciones con industria local.

Fíjate en esta diferencia sutil: esto no se trataba de aumentar las exportaciones industriales. Se trataba de reemplazar importaciones industriales. Esto cambió por completo la mentalidad, pasando de un modelo en el que las empresas locales campeonas tenían que mejorar agresivamente su productividad para competir en el exterior, a uno en el que las campeonas locales estaban protegidas del exterior.

¿Por qué importa? Porque las exportaciones son imposibles de falsificar. Si ganas en mercados mundiales es porque eres el mejor. Pero si ganas en el mercado local… simplemente eres bueno consiguiendo que Papá Estado te proteja a ti y a tu falta de productividad contra competidores internos y externos.

El Estado argentino usó:

Barreras a las importaciones, como aranceles o cuotas contra competidores internacionales

Préstamos baratos a empresas industriales locales

Tipos de cambio diferentes para las exportaciones agrícolas y las importaciones industriales, de modo que las industrias pudieran comprar con descuento

Empresas estatales

Subsidios, como electricidad o transporte ferroviario por debajo del costo

Exenciones fiscales

Todas estas herramientas eran similares a las utilizadas por los Tigres Asiáticos. La diferencia fue cómo se usaron.

Disciplina exportadora

Esta es, de lejos, la diferencia más importante. Estas ayudas no estaban condicionadas a ganar en los mercados globales como en Asia, así que la mayoría de estas empresas simplemente se quedaron en el mercado local argentino, protegidas de la competencia. Mantuvieron precios altos y vivieron de las rentas.

Mientras tanto, el resto del país tenía que desembolsar más dinero para comprar los mismos electrodomésticos que habrían sido mejores y más baratos en el extranjero. Terrible.

Economías de escala

La disciplina exportadora tiene otra ventaja: una empresa exportadora tiene un mercado potencial enorme. Esto es especialmente importante si hay un costo inicial elevado. Imagina que quieres hacer acero. Necesitas una fábrica enorme, así que más te vale tener un mercado capaz de comprar millones de toneladas para amortizar el costo inicial. Si tu mercado es pequeño—como el mercado argentino—nunca tendrás suficientes clientes para alcanzar economías de escala, y tus costos siempre serán demasiado altos.

Los costos de las fábricas de autos en Argentina, Brasil y México eran aproximadamente entre un 60% y un 150% más altos que en Estados Unidos.

—Import Substitution in Latin America, Baer

La industria del papel (excluyendo papel prensa) tenía 292 plantas de las cuales solo 25 tenían una capacidad de 100 toneladas diarias, que se considera el tamaño mínimo económico. En la industria química también hay muchísimos casos en los que existe una gran brecha entre los tamaños de planta más frecuentes en la región y los tamaños construidos en los países industrializados.

—Import Substitution in Latin America, Baer

Que sea lo que Dios quiera

Cada vez que das un préstamo barato, subvencionas un costo o aumentas un arancel, le cuesta dinero al Estado. Es como un impuesto para todos los demás. Por lo tanto, el Estado debe ser extremadamente cuidadoso. No puede apoyar jugadores locales en todas las industrias; tiene que elegir las pocas industrias clave que va a apoyar y concentrar todos sus recursos allí.

Normalmente esto se hace en industrias que son fundamentales para el futuro del país. En el caso de Japón y Corea del Sur, ambos apostaron por el acero como insumo clave para luego producir industrias pesadas como automotrices. Ahora conoces Toyota, Nissan, Mazda, Subaru, Hyundai, Kia… Pero puede que no conozcas a la poderosa Nippon Steel o a Hyundai Steel21 o POSCO.

Dentro de las industrias con las que Argentina decidió jugar, debería haber encontrado a las ganadoras y apoyarlas solo a ellas, empujando a las demás a morir o fusionarse. Es más fácil apoyar una gran empresa que un montón de pequeñas. Por ejemplo, Argentina tuvo más de una docena de fabricantes de autos, lo cual está bien para empezar22, pero ¡hay que lograr que se fusionen!

En Argentina, la diversificación excesiva, la capacidad ociosa, los grandes inventarios debido a los controles de importación y las dificultades para obtener financiación externa explican el alto nivel de precios en la industria de equipos eléctricos pesados.

—Import Substitution in Latin America, Baer

Ventaja comparativa

No basta con elegir unas pocas industrias. El enfoque debería limitarse a aquellas donde Argentina tuviera una ventaja comparativa. No puedes ser bueno en todo. Elige tus batallas. Por ejemplo, dada su potencia agrícola, ¿podría haber impulsado empresas de maquinaria agrícola? Tenían Vassalli, Senor, Pauny, Zanello y Araus.23 ¿Podría haber producido el John Deere argentino si hubiera tenido más apoyo?

¿Qué otras industrias podría haber elegido Argentina? ¿Frigoríficos y procesamiento de carnes? ¿Ferrocarriles? ¿Construcción naval? ¿Metalurgia, nuclear, instrumentos de precisión?

En cambio, apoyó empresas de electrónica como BGH, Newsan, SIAM o Philco. Pero la electrónica es una industria de márgenes muy bajos en la que Argentina no tiene ventaja competitiva y necesitas exportar para alcanzar la escala suficiente que abarate los costos. Tal como fue, los argentinos tuvieron que gastar mucho más para obtener peores televisores, y en el proceso se gastó hasta un 1% del PIB en subvencionar la industria.24 Otro ejemplo son los textiles y la confección. ¿De verdad quieres competir con India o Bangladesh, con sus salarios bajísimos y márgenes inexistentes?

Alta compensación

Hablando de salarios, los Tigres Asiáticos mantuvieron salarios bajos durante mucho tiempo para mantener bajos los costos de producción. Lo hicieron, entre otras cosas, trabajando con los sindicatos, que entendían que necesitaban un largo periodo de salarios bajos para volverse competitivos y solo entonces podrían aumentarlos.

Los argentinos tenían la visión opuesta. Crecieron experimentando alta desigualdad por las exportaciones agrícolas, así que querían aplicarles impuestos para redistribuir la riqueza al pueblo. La producción industrial (y las exportaciones, cuando existían) se veía como otra fuente de dinero a la que aplicar impuestos. La mentalidad completamente opuesta a la de Asia, con el resultado de salarios más altos, costos mayores, menos competitividad y la ausencia de campeones globales.

Se obligó a los empleadores a mejorar las condiciones laborales y a proporcionar indemnización por despido y compensación por accidentes, se restringieron las condiciones bajo las cuales se podía despedir a trabajadores, se estableció un sistema de tribunales laborales para gestionar los reclamos de los trabajadores, se redujo la jornada laboral en varias industrias y las vacaciones pagas se generalizaron a toda la fuerza laboral. Perón también aprobó una ley que establecía salarios mínimos, máximas horas de trabajo y vacaciones para los trabajadores rurales, descanso los domingos, vacaciones pagas, congeló los alquileres rurales, presidió un fuerte aumento de los salarios rurales y ayudó a organizar a trabajadores madereros, vitivinícolas, azucareros y migrantes. Perón estableció dos nuevas instituciones que incrementaron los salarios: el “aguinaldo” (un bono que proporcionaba a cada trabajador una suma al final del año equivalente a una doceava parte del salario anual) y el Instituto Nacional de Remuneraciones, que implementó un salario mínimo y recopilaba datos sobre nivel de vida, precios y salarios.

De 1943 a 1946, los salarios reales crecieron solo un 4%, pero de entonces a 1948 (bajo Perón) crecieron un 50%.

Los subsidios a energía, alimentos, vivienda y transporte tenían el mismo efecto de aumentar la compensación efectiva.

Tomemos la vivienda: el gobierno de Perón construyó cientos de miles de casas. Suena bien, pero tiene muchos problemas:

Podemos verlo como si todo el país guardara dinero para comprarle una casa a unos pocos. ¿Quién consigue esas casas? ¿Amigos de los políticos? ¿Son los beneficiarios los más merecedores? ¿Los que más las necesitan?

¿De dónde sale ese dinero? Si no es una fuente sostenible (pista: los booms agrícolas y sus crashes no lo son), es una receta para el desastre.

El costo de construir más viviendas sube (ya que el gobierno ahora sobrepuja al mercado privado), haciendo más difícil para los demás conseguir una casa. Si quieres que todos tengan una casa, lo primero es concentrarte en bajar todos los costos de construcción.

Todas estas cosas (vivienda, vacaciones, jubilación…) son objetivos estupendos para un país, pero fue demasiado pronto para tener tantas. Los empleados solo pueden ganar tanto como producen. Cuando no son muy productivos (es decir, al inicio del camino de desarrollo de un país), lo que logran estas medidas es aumentar los costos de las industrias hasta el punto de volverlas no competitivas y hacer que desaparezcan o tengan que ser subsidiadas por el gobierno—es decir, el gobierno aplica impuestos a las partes productivas de la economía (aquí, la agricultura) para subvencionar altos niveles de vida a los trabajadores industriales, que no son lo suficientemente productivos como para pagarlos por sí mismos.

Sindicatos

¿Cómo llegó Argentina a una situación tan problemática, donde los salarios superaban a la productividad? Un factor clave son los sindicatos. Aproximadamente el 40% de los trabajadores legales están sindicalizados en Argentina, y estos sindicatos tienen un poder enorme.

En general, creo que la mejor forma de mejorar la posición de los trabajadores es el pleno empleo, ya que la competencia entre empleadores mejora las condiciones. Sin embargo, a veces este proceso no es óptimo y los sindicatos pueden ayudar a equilibrar el poder entre trabajadores y empleadores. Pero la clave es el equilibrio.25

No hubo suficiente equilibrio en los sindicatos en Estados Unidos a mediados del siglo XX, lo que fue la principal causa de la desindustrialización del Rust Belt: las industrias se fueron al Sur, mucho menos sindicalizado y con costos más bajos. Algo parecido ocurrió en Argentina.

¿Pero de dónde viene el poder de los sindicatos argentinos? Antes de tomar el poder, Perón fue Secretario de Trabajo. Allí se alió con los sindicatos. Gracias a ellos llegó al poder. Como su base de poder venía de los sindicatos, él los protegía y ellos lo protegían a él. La forma más obvia es la Personería Gremial: ¡cada sector industrial solo tiene un sindicato legal! ¡Y todos están bajo la órbita de una central, la CGT! ¿Te imaginas el nivel de poder que tiene la CGT?26 Luego, Perón hizo que la negociación colectiva fuera universal y ejecutable por el Estado.

Por supuesto, tal concentración de poder se tradujo en poder político y en una puerta giratoria entre la política y los sindicatos que llevó a la corrupción.

Hoy, Argentina sigue teniendo una legislación de protección del empleo más estricta que otros países latinoamericanos.27

Nada de esto ocurrió en los Tigres Asiáticos. Corea del Sur y Taiwán fueron los más radicales (ambos lucharon contra comunistas en sus respectivas guerras civiles) y sus gobiernos controlaban los sindicatos, que tenían poder limitado. También había sindicatos en Japón, pero bajo supervisión gubernamental. Un hecho crucial es que los sindicatos estaban mucho menos centralizados. Por ejemplo, en Japón, cada empresa tiene su propio sindicato. Esto implica dos cosas:

Los sindicatos son más débiles, pero lo suficientemente fuertes como para enfrentarse al empleador.

Están atados al futuro de la empresa, por lo que les interesa enormemente que la empresa tenga éxito y no les importa el desarrollo económico de todo el país.

Menor productividad agrícola

El alto costo y bajo valor de la maquinaria agrícola local fue especialmente dañino para la gallina de los huevos de oro de Argentina: la agricultura. Si los agricultores hubieran podido comprar máquinas internacionales, podrían haber aumentado masivamente su productividad, lo que habría generado más exportaciones y riqueza para el país. Pero la sustitución de importaciones lo hizo imposible.

Resistencia a la integración vertical

Los países asiáticos apoyaron industrias fundamentales como el acero. Esto importa porque una vez que eres competitivo en algo como el acero, tienes ventaja para integrarte verticalmente—fabricar cosas más abajo de la cadena más baratas, como autos. Lleva tiempo y esfuerzo, pero los Tigres Asiáticos lo hicieron invitando a empresas extranjeras a sus países y asegurándose de que hubiera transferencia tecnológica entre extranjeros y locales.

Argentina a menudo apoyó la sustitución de importaciones en bienes de consumo. Aquí los incentivos son opuestos, porque si produces bienes de consumo, probablemente importas mucha maquinaria y materiales del exterior. Si empiezas a fabricar tú mismo estas máquinas y materiales, es probable que los hagas peor y más caro, lo que hará tus productos de consumo más malos. Así que las empresas presionaron al gobierno para evitar desarrollar insumos intermedios domésticos.

Si el gobierno hubiera insistido, tal vez Argentina podría haber integrado verticalmente, pero no lo hizo, y el país no capturó cadenas de valor.

Como ves, esta es una lista bastante demoledora de diferencias. ¡No es de extrañar que Argentina no tenga campeones industriales o de consumo globales!

3. Gestión financiera y fiscal

Ya parece una lista enorme de errores. Pero no hemos terminado. Es hora de hablar de los errores financieros y fiscales.

Pérdida de productividad de la tierra

¿Recuerdas qué hablamos sobre los impuestos a las exportaciones de granos y carne? Esto puede ser bueno o malo, según cómo se use el dinero. La desventaja de impuestos tan altos es que los agricultores pueden subinvertir: hay menos excedente para comprar más tierra, mejorar la fertilización, adquirir más maquinaria, construir mejores sistemas de riego… La rentabilidad de la inversión baja. Así, esta tributación reduce la producción a largo plazo.

Los Tigres Asiáticos intervinieron con frecuencia en la venta internacional de los cultivos de sus países, pero también reinvirtieron mucho de ese dinero en el sector agrícola, por lo que la producción agrícola a largo plazo mejoró. De hecho, estos países quizá financiaron mejor su agricultura con estos impuestos que sin ellos, porque obligaron a hacer inversiones en las granjas que los agricultores tal vez habrían preferido ahorrar o invertir en otra parte.

No es lo que hizo Argentina. Por lo que puedo ver, sí invirtió algo de dinero para apoyar a la agricultura, en cosas como puertos y silos, pero la mayor parte del dinero no volvió al campo. Esa es probablemente otra razón por la que la productividad agrícola empezó a divergir entre Argentina y Estados Unidos.

Rendimiento bajo

Entonces, ¿en qué gastó el Estado argentino ese excedente? Entre otras cosas, invirtió en el país:

Pagó la deuda nacional.

Nacionalizó todo el sistema bancario, incluyendo el banco central (que antes estaba controlado por el Reino Unido).

Nacionalizó los ferrocarriles.

Creó una flota mercante.

Las obras públicas ampliaron el acceso al agua potable y al saneamiento.

Invirtió en exploración de carbón y petróleo, construyó el primer gasoducto y desarrolló centrales eléctricas, represas hidroeléctricas y refinerías.

Algunas de estas fueron buenas inversiones. Por ejemplo, pagar la deuda nacional permite endeudarse en el futuro. Construir infraestructura energética reduce el costo de la energía y genera exportaciones de energía, ambas cosas estupendas para el país. Es bastante importante controlar tu propio banco central.

Otras son peligrosas. Si nacionalizas la mayor parte del sistema bancario,

eliminas la información que aportan los banqueros;

pierdes el incentivo para encontrar los mejores lugares donde asignar tu dinero.

Ambas cosas llevan a un menor retorno del capital.

No solo puede ser problemático el tipo de financiación, sino también su magnitud. Durante los primeros mandatos peronistas en los años 40 y 50, el Banco de Crédito Industrial financió el 52% de toda la actividad industrial, con picos de hasta el 78% en 1949. Es demasiada plata, demasiado concentrada en el Estado, lo que lleva al despilfarro y la corrupción.

Corea del Sur y Taiwán también nacionalizaron el sistema bancario, pero lograron mantener una buena asignación financiera porque sus gobiernos eran menos corruptos y más tecnocráticos. Argentina era demasiado propensa al populismo y a la corrupción, y su sistema bancario no era tan eficiente. Muchos préstamos fueron a aliados políticos en lugar de a campeones industriales estratégicos y eficientes.

Inversión extranjera directa

Expropiar las inversiones de extranjeros en tu país es una forma perfecta de garantizar que no vuelvan a invertir.

Como Argentina creció durante el apogeo del Reino Unido, la mayor parte de su inversión extranjera venía del país más rico del momento, el Reino Unido: ferrocarriles, comercio marítimo, bancos… Esta financiación fue crucial para el desarrollo argentino, pero tenía sus contras. Por ejemplo, Argentina tenía una naciente industria de lana y confección en el siglo XIX, pero cuando llegaron los británicos y financiaron ferrocarriles, uno de los objetivos era llegar muy al interior con sus productos de algodón. La industria textil local colapsó.

Cuando el Reino Unido perdió poder durante las guerras mundiales, no estaba en posición de seguir financiando Argentina. Esto, sumado a la gran cuota que ya controlaba,28 implicaba que Argentina no era dueña de su propio destino financiero, lo que fue otro factor del populismo: Perón acusó al Reino Unido de imperialismo, así que cuando se nacionalizó el sistema bancario, el objetivo no era “vamos a invertir este dinero de forma prudente” sino “vamos a hacer lo que queramos con este dinero, independientemente de lo que estos ex imperialistas querían que hiciéramos”.

Gasto público

(A diferencia de la inversión)

¿Recuerdas los altos salarios de los que hablamos antes? Esta cita es de justo después del segundo mandato de Perón:

En la Argentina el exceso del gasto público sobre el ingreso ha sido en su mayor parte no para hacer gastos productivos, sino para pagar gastos improductivos, o sea, salarios de la administración pública o déficit operativo de las empresas estatales

—Anuncio radial del nuevo plan económico por radio y televisión nacional en Argentina tras el golpe, IADE, del nuevo Ministro de Economía, Martínez de Hoz, 2 de abril de 1976.

Salarios, funcionarios, pensiones, subsidios… Estos altos costos fueron una de las mayores fuentes de déficit público, y no solo bajo Perón. Por ejemplo, en 2008 el Estado subvencionaba al 77% de los beneficiarios de los fondos de pensiones privados. El punto de las pensiones privadas es precisamente que el riesgo lo asumen los ciudadanos, no el Estado.

Sobre-gasto durante los booms

Invertir tanto dinero de tiempos de bonanza también provoca un problema de temporalidad.

Noruega es otro país que gana mucho dinero cuando los mercados internacionales están boyantes, porque vende mucho petróleo. Pero no permite que el dinero de sus excedentes inunde la economía. Lo mantiene en un fondo soberano que invierte por todo el mundo y solo usa sus rendimientos reales para financiar al gobierno (alrededor del 3% del fondo cada año). Esto suaviza completamente el gasto público durante décadas,29 de manera que cuando los precios del petróleo se hunden unos años, el país casi ni lo nota.

Argentina no hizo eso. Dada la enorme exposición a exportaciones de materias primas y las brutales oscilaciones de precio que sufren en los mercados internacionales, Argentina tuvo enormes superávits en los años de bonanza. Se desbocó en el gasto durante esos booms, como vimos con la enorme lista de proyectos que emprendió Perón.

Lo mismo ocurrió en el último mandato de Perón (1974-1975). Mira el pico de los precios de las materias primas:

Entre 1972 y 1975, el número de empleados públicos aumentó un 24% (en los 10 años anteriores habían aumentado un 7,4%, es decir, un 90% más lento). Esto tuvo muchas consecuencias negativas.

Una fue reducir aún más el retorno de la inversión. Por ejemplo, si construyes viviendas durante 10 años, el flujo es constante, los constructores pueden predecir cuánto ganarán, pueden invertir a largo plazo, contratar empleados, incrementar la maquinaria y mantener precios bajos. Pero si toda esa inversión se concentra en un par de años, no les da tiempo de aumentar su capacidad, así que simplemente piden un precio mucho más alto. Eso significa menos valor por cada peso gastado.

Sobrevaluación del peso

Otra consecuencia del sobre-gasto en tiempos de bonanza es la sobrevaluación de la moneda local, común en países que exportan materias primas:30

Los exportadores de un país venden alguna materia prima en el mercado internacional y ganan muchos dólares.31

El gobierno aplica impuestos a una gran parte.

El gobierno quiere gastar ese dinero en su país, así que vende los dólares y compra moneda local.

Esto aumenta el valor de la moneda local.

Esto hace que otros tipos de exportación sean más caros, así que se reducen.

La única salida es la esterilización, que tiene sus propios problemas.32

Otra forma de decirlo es que, durante un boom de materias primas, el gobierno gasta mucho más en la economía local, aumentando precios y salarios internos. Con costos más altos, las empresas locales (que compiten por los mismos recursos) son menos competitivas en el exterior.

Recuerda lo que hicieron los Tigres Asiáticos. Sus bancos centrales compraban los dólares de los exportadores y los guardaban, comprando bonos del Tesoro de EE. UU. y manteniéndolos en sus reservas. Si los hubieran vendido en los mercados internacionales para comprar moneda local, habrían fortalecido su moneda. Al evitar eso, permitieron que los exportadores industriales vendieran barato.

Argentina podría haber hecho lo mismo, pero no lo hizo por su pecado original: la desigualdad en la agricultura. La redistribución de riqueza se convirtió en un problema político, especialmente desde Perón. El gobierno aplicaba impuestos sistemáticamente a las exportaciones y redistribuía de inmediato los ingresos mediante los altos salarios que vimos, además de otras formas de inyectar dinero en la economía (aumentos de pensiones, más empleados públicos…).

Inflación

La sobrevaluación del peso en tiempos de bonanza es también una de las fuentes de los famosos ciclos inflacionarios de Argentina. Recuerda que hubo un aumento de precios de materias primas a principios de los años 70. Mira la inflación argentina justo después:

¿Por qué el pico de inflación?

Este es el déficit del gobierno. Creció desde 1970, alcanzando un máximo en 1975 de casi el 14% del PIB. En ese punto, los impuestos solo cubrían el 20% del gasto público. El gobierno cubrió el 80% restante imprimiendo dinero y endeudándose, lo que llevó a inflación.

¿Pero por qué hubo ese déficit en primer lugar? Por el aumento del gasto del que hablamos antes: más empleados públicos, salarios más altos, subsidios, más inversión… Si resumimos este ciclo inflacionario:

Suben los precios de las materias primas.

Aumentan las exportaciones agrícolas.

Los ingresos del gobierno se disparan.

El gobierno gasta de más.

Termina el boom de materias primas.

El sobre-gasto ya no se cubre con impuestos a las exportaciones.

El gobierno imprime dinero para cubrir el sobre-gasto.

Inflación.

Ciclos posteriores no fueron todos impulsados por booms de exportaciones agrícolas, sino por algunas consecuencias de ciclos anteriores. Por ejemplo, a finales de los 80:

Argentina tenía un enorme déficit y no podía cubrirlo con nueva deuda.

Así que imprimió muchísimo dinero (¡más de 40x la base monetaria en un año!).

¿Por qué el enorme déficit?

Porque venía acumulando déficits desde hacía mucho.

Así acumuló una deuda gigantesca.

Los pagos de intereses sobre esa deuda se acumularon, empeorando el déficit.

¿Por qué no podía cubrir el déficit con nueva deuda?

Por la enorme deuda, como ya dijimos.

Porque los mercados internacionales no estaban disponibles: Argentina había entrado en default en 1982, ya que su deuda era muy alta.

Una mezcla de ambas cosas ocurrió con los Kirchner a mediados de la década de 2010.33

Cuanto más a menudo se repite el ciclo, más aprende la gente a esperarlo, y más difícil es controlarlo:

La inflación sube simplemente porque la gente la espera, así que suben los precios.

El valor del peso cae porque la gente espera que pierda valor, así que venden sus pesos para comprar dólares. Esto acelera el proceso.

¿Cómo evitaron esto los Tigres Asiáticos? Al principio, no tenían el mismo “lujo” de grandes exportaciones agrícolas que trajeran montones de dólares, así que no tenían un historial de booms de materias primas como Argentina. Dicho esto, el gasto público nunca aumentó tan rápido como las exportaciones, al revés: los gobiernos asiáticos guardaban los dólares en forma de bonos del Tesoro de EE. UU., como se explicó. La desventaja fue menos gasto social a corto plazo. La ventaja fue más productividad, moneda local infravalorada, más exportaciones, más acumulación de riqueza y más reinversión a largo plazo. Me recuerda a la fábula de la cigarra y la hormiga.

Defaults

Desde su independencia, Argentina ha entrado en default nueve veces (tres en el siglo XXI). Se ve claramente cómo esto es consecuencia directa de las acciones anteriores.34

Ahorro

Mientras que los Tigres Asiáticos obligaron a sus ciudadanos a mantener el dinero en bancos locales para reinvertirlo en la industria, esto no ocurrió en Argentina, que renunció a esta palanca demasiado pronto en su desarrollo: no ha obligado a los bancos argentinos a concentrar préstamos baratos en la industria local y, desde 1993, perdió su gran banco de desarrollo industrial. Su sucesor es mucho más pequeño y menos ambicioso.

Empresas estatales

No se justifica de ninguna manera … que el Estado tenga a su cargo empresas azucareras, metalúrgicas, textiles y de todo orden, con el pretexto de mantener las fuentes de trabajo. —Anuncio radial del nuevo plan económico por radio y televisión nacional en Argentina tras el golpe, IADE, del nuevo Ministro de Economía, Martínez de Hoz, 2 de abril de 1976.

Las empresas estatales (EE) pueden tener un lugar. Por ejemplo, en monopolios naturales. Pero los Estados a menudo intentan controlar más empresas de las que deberían: pueden aportar dinero y poder al Estado y a los políticos, que podrían usarlos para su propio beneficio.

Además de ser una oportunidad de corrupción, las EE suelen ser ineficientes porque sus dueños no buscan maximizar beneficios.

Por ejemplo, antes de la privatización telefónica en 1990:

Para conseguir una nueva línea no era raro esperar más de diez años, y los apartamentos con línea telefónica tenían una gran prima en el mercado frente a departamentos idénticos sin línea. Tras la privatización, la espera para tener teléfono se redujo a menos de una semana.

—Culture and Social Resistance to Reform: A theory about the endogeneity of public beliefs with an application to the case of Argentina, Pernice & Sturzenegger

Además, cuando las EE pierden dinero, el gobierno acude a cubrir el agujero en lugar de permitir que una empresa improductiva muera y que otras más productivas tomen sus recursos y su mercado.

Eso es lo que ocurría en Argentina, donde en 1976 el gobierno financiaba todas las pérdidas de los ferrocarriles, que eran mayores que los presupuestos regionales de todas las provincias combinadas (fuera de Buenos Aires).

Entonces, ¿por qué es pobre Argentina?

Resumamos para ver los patrones.

Primero, la tierra argentina es extremadamente fértil. Esto es genial porque genera mucho dinero para el país y es la razón por la que fue rico entre 1890 y 1930. Pero tiene algunos lados negativos:

Requiere una gestión delicada de la moneda para evitar la sobrevaluación del peso y la inflación.

Como los mercados de materias primas fluctúan salvajemente, los ingresos del país también lo hacen.

Segundo, probablemente por la cultura heredada de España, pero también por cómo obtuvo su independencia, la tierra en Argentina estaba muy concentrada y nunca se redistribuyó entre los trabajadores rurales. Esto llevó a una gran desigualdad y, en consecuencia, a enojo.

Esto empujó a los políticos argentinos a encontrar otra forma de redistribuir la riqueza agrícola: no a través de la tierra, sino financieramente, controlando y aplicando impuestos a las exportaciones del campo. Por desgracia, esto significó que las enormes oscilaciones de los mercados internacionales de materias primas se convirtieron en oscilaciones de los ingresos del gobierno.

La combinación de ambos factores es extremadamente problemática: el primero (no redistribuir la tierra) conlleva la redistribución financiera para reducir la desigualdad (o te enfrentas a un conflicto), pero es difícil redistribuir de un modo que siga los vaivenes de los mercados internacionales, así que, en lugar de eso, la redistribución fue tan generosa que fue derrochadora durante las bonanzas y llevó al gobierno a enormes agujeros presupuestarios en las épocas de crisis.

El despilfarro en tiempos de bonanza se ve en los enormes aumentos de compensación a los trabajadores que se produjeron entonces, el enorme sistema de protección social, la financiación excesiva de industrias, las nacionalizaciones, la creación de empresas estatales…

Los agujeros en tiempos de crisis llevaron a todo tipo de problemas como hiperinflación, defaults, devaluaciones… El desorden económico, a su vez, llevó a inestabilidad política, que condujo a inestabilidad institucional.

Un tercer factor que añadir a la mezcla es la exposición de Argentina a inversores extranjeros (sobre todo el Reino Unido): como alcanzó su independencia mucho más tarde que Estados Unidos y estaba más lejos del Reino Unido cultural y geográficamente, su revolución industrial llegó mucho más tarde. Cuando el Reino Unido era rico (y podía invertir), Argentina seguía siendo una sociedad agraria, así que no podía invertir en sí misma y la mayor parte de la inversión venía de Londres. Esto expuso a Argentina a los extranjeros, lo que generó inseguridad y un deseo de autosuficiencia. Esto se ve en las nacionalizaciones, los impuestos tanto a importaciones como a exportaciones, la política de sustitución de importaciones, la sobrefinanciación de industrias nacionales, el proteccionismo…

Muchos de estos factores tuvieron un impacto dramático en la industria:

Sobre-subvencionada por el gobierno.

Protegida de la competencia extranjera.

Compensación laboral demasiado alta.

Sometida a la sobrevaluación del peso y a la inflación, que encarecían los costos o hacían imprevisible la inversión.

Bajo acceso a inversión y tecnología extranjeras.

Competencia de empresas estatales.