What Did a Two-State Solution Look Like?

When Peace Was Within Reach

At two points in time, it looked like a peace agreement between Israelis and Palestinians was within reach. They seemed so close! What did the deal look like? What did they negotiate? Why didn’t they sign? This is what we’ll answer today.

The devil is in the details.

There have always been four main areas of debate between Israel and Palestine: territory, security, Jerusalem, and the right to return. If we understand these four, we understand why Israelis and Palestinians nearly reached a peace agreement.

Israelis and Palestinians have been very close to reaching a peace agreement on these topics twice:

In 2000-2001, US President Bill Clinton, Palestinian Authority chairman Yasser Arafat, and Israeli Prime Minister Ehud Barak tried to find a peace agreement during the Camp David Summit, in the summer of 2000, followed by negotiations in Taba, Egypt, in January of 2001.

In 2007-2009, in the Annapolis Process, Ehud Olmert, then Prime Minister of Israel, and Palestinian President Mahmoud Abbas nearly reached an agreement.

Let’s see how each of the four key issues evolved through these processes:

1. Territory Borders

The Gazan territory is pretty well established. It hasn’t moved since 1948 (it’s just been taken over by Israel in the Six-Day War of 1967), and there are no Jewish settlements there anymore. So, when discussing territories and borders, the only debate concerns the West Bank.

In the last article, we saw that Israel devolved Area A (and partially B) to Palestinians in the Oslo Accords, and they were supposed to reach a final agreement within five years, but didn’t. This is where things stood in early 2000:

In the months leading up to Camp David, when Ehud Barak and Bill Clinton were pushing hard for a peace agreement, Barak proposed several maps to finalize the borders. We don’t know for sure what these maps entailed, but people have tried to reconstruct them based on references from those concerned. Here are some:

There are a few things to notice from these maps. First, there is a consistent reduction in territory claims from Israel.

In the West Bank, for example, the alleged map from May 2000 offered the Palestinians 66% of the West Bank (the brown area), with 17% annexed to Israel (in white), and 17% not annexed but under Israeli control (the green, for security purposes). By Camp David, in mid-July 2000, Israel proposed to keep only 8-15% of the West Bank.1

In exchange for this land, there would be land swaps—something along these lines:

Besides this, Israel would give Palestine about 70-200 km2 of land near Gaza and the Egyptian border, in a region called the Haluza Sands, in the Negev desert. Palestinians thought this land was not as good as the land the Israelis wanted in the West Bank, and argued this was giving up 9 km2 for every km2 they were getting, so it was unacceptable. The Israelis considered the ratio to be closer to 1.5 to 1.2

Another thing to notice is the shape of the maps. Palestinians argued that Israelis wanted to split the West Bank into three pieces; Israelis deny this. The contrast between the two maps below illustrates this:

So which one of these versions is true? If you pay attention to the details, both maps annex a bunch of settlements into Israel. The difference is in three lines: the Jordan Valley border, and two paths going from there to the closest settlements. We’ll talk about the Jordan Valley in a moment.

The Palestinian version on the left map suggests there were two big corridors containing settlements splitting the West Bank. Israelis defend that there was only one, and it was not a corridor, just a road:

The Palestinians were promised a continuous piece of sovereign territory except for a razor-thin Israeli wedge running from Jerusalem through from [the Israeli settlement of] Maale Adumim to the Jordan River.—Ehud Barak, Morris, “Camp David and After,” p. 44. Enderlin, Shattered Dreams, p. 201, via this.

This matters, because just a road is easy to bypass with bridges and tunnels, whereas a full corridor is much harder to deal with.

Sectioning the West Bank and taking additional land was not acceptable to Palestinians, and this is one of the reasons why Arafat and Barak didn’t reach an agreement at Camp David.

In this plan and most others, Israeli settlers living in parts of the West Bank that were not included into Israel would either have to move to Israel or live in Palestine as Palestinian citizens.

By December 2000, Bill Clinton proposed his parameters for peace3, proposing that Israel would keep 4-6% of West Bank land, down from 8-15%. Israel would compensate Palestine with 1-3% from Israeli land4. Parameters for good swaps were spelled out:

80% of Jewish settlers in the West Bank would be included in Israel, swapped with Israeli.

These swaps would not jeopardize the contiguity of either Palestine or Israel.

They would minimize the annexed land and the number of Palestinians affected.

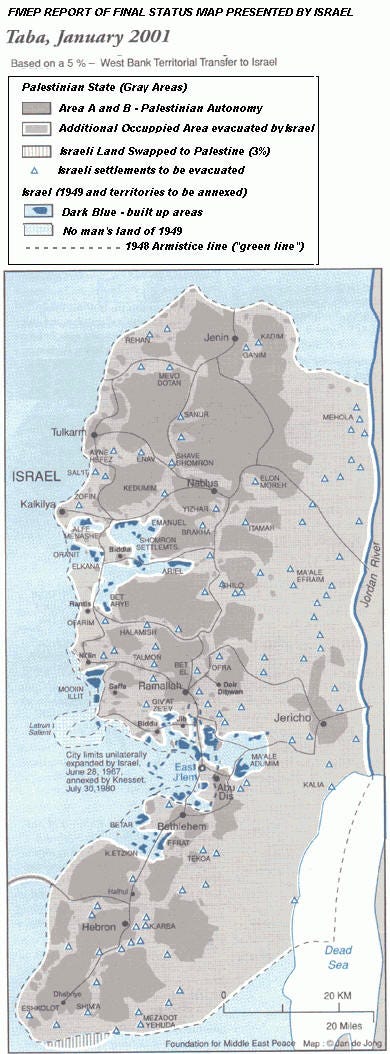

The next month, in Taba, this is what Palestinians and Israelis used as a basis for negotiation. We know where they landed, because Ambassador Moratinos from the EU took accurate notes of the negotiations.5

The Israelis adhered to Clinton’s parameters and proposed keeping 6% of the West Bank and swapping it for 3% of Israel’s territory. This unofficial map shows what Israel wanted to keep:

The Palestinians were a bit more aggressive, proposing swaps of 3% of West Bank territory for the same amount of Israeli land.6

3% of freaking land. The West Bank has 5,860 km2 of surface area. That’s 175 km2, or about the size of a city like San Jose, California, or Pisa, Italy. This was the biggest obstacle to peace in the Middle East.

Outrageous.

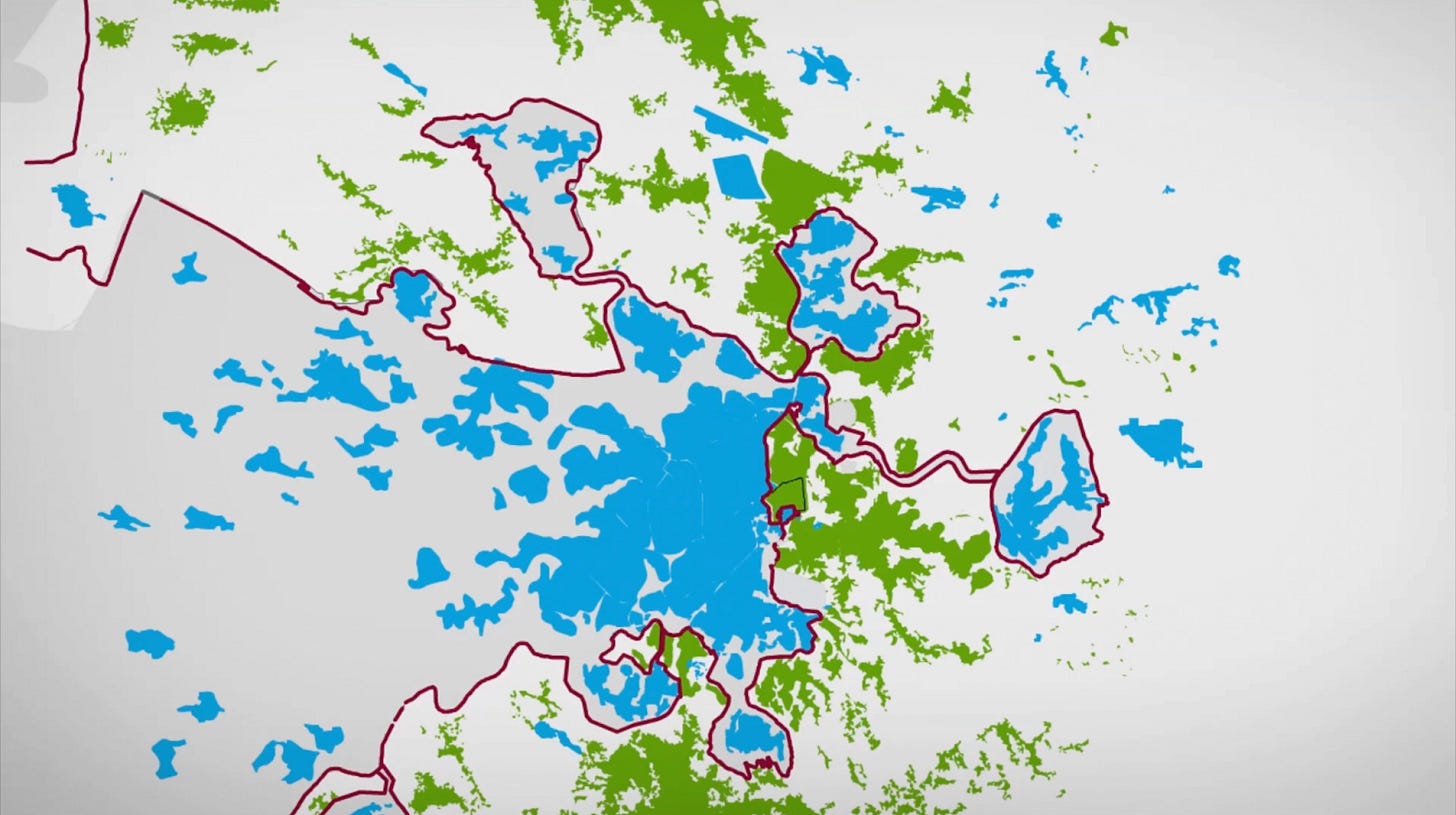

This is how close they got in 2009, when Mahmoud Abbas and Ehud Olmert were negotiating:

It’s not full agreement, but how close is it?! In Olmert’s plan, the Palestinian state would get a land area equal to 99.5% of the West Bank and Gaza: Israel would annex 6.3% of Palestinian territory, and would compensate the Palestinians with Israeli lands equivalent to 5.8%, as well as a corridor to connect Gaza and the West Bank.

Mahmoud Abbas and Ehud Olmert described the negotiations as serious and said a peace deal was achievable.—Source.

Just to give you a sense of how close this was, this was the last proposal in the Trump Peace Plan in 2020:

This is much more generous with Israel than the previous plans—something that Ehud Barak and Ehud Olmert had alerted Palestinian leaders would happen. So much so, that Palestinians never entertained it.

2. Security

We talked in a previous article about Israel’s key goal of security. Given its track record with Arab neighbors and Palestinian violence, its security is a very high priority. That means protection against foreign attacks from the east, aerial threats like rockets, and standard terrorism.

At Camp David, when considering the division of land, Israel thought it needed the following:

Control the Jordan Valley to protect against an Arab invasion from the east via the new Palestinian state, for between 6 and 21 years.7

Three early warning stations (aka military bases, I assume) in the West Bank.

Demilitarization of the Palestinian state.

This was not acceptable to Palestinians, since they would be giving up so much potential sovereignty—especially with Israel keeping the Jordan Valley for so long, maybe indefinitely. Having a demilitarized state also exposed Palestine to being taken over by Israel again.

However, Palestinians might have relented about the military. A Palestinian state would have its own police, which would coordinate with Israel on counter-terrorism, but Israel’s military wouldn’t be able to come into Palestine like it does now.

The Palestinian state would control its airspace for civil purposes, but above a certain altitude, Israel would control it. Palestine would have no navy or air force and would not be able to enter military alliances with other countries. In other words: The defense of Palestine would be the responsibility of Israel, and Palestine would never pose a military threat to Israel, but it would gain full sovereignty over its local security and would only coordinate with Israel on that topic.

I’ve also seen statements about Israel potentially maintaining some forces in West Bank early warning stations.

Overall, although Israel and Palestine don’t see eye to eye on everything related to security, it looks like they agree on the broad lines.

3. East Jerusalem

The problem of East Jerusalem consists of two pieces: the actual city, and the religious sites.

East Jerusalem, the City

Israel and Palestine both want Jerusalem as their capital. This appears complicated: West Jerusalem was part of Israel and East Jerusalem part of Jordan until 1967, when Israel took over the East in the Six-Day War and annexed it.

This is a map of East Jerusalem today:

Solving this Jenga is easier than it seems, because although Israelis and Palestinians have been living within Jerusalem proper for decades, their neighborhoods are still mostly separated.

This has one simple solution: Split the people.

This would mean splitting a city in half, which would not be great for municipal management. It would also require putting up even more walls and checkpoints throughout the city. But these are not insurmountable problems.

The alternative is better for the municipality, but worse for the states: a single, open city, where citizens from both sides could move freely.

But then there would be more mixing of populations, potentially more conflict, and city-dwellers would have to go through checkpoints to visit the rest of their country.

In Taba, Palestinians were interested in this option, but Israelis only considered the Open City concept for the Old City of Jerusalem.

The Old City of Jerusalem: the Religious Dimension

This is a factor many Westerners underestimate, because its religious dimension has no meaning to them. But it is existential for both sides.

The Dome of the Rock is the world's oldest surviving work of Islamic architecture, the earliest archaeologically attested religious structure to be built by a Muslim ruler, and its inscriptions contain the earliest epigraphic proclamations of Islam and of the Islamic prophet Muhammad.

It is built over the Foundation Stone (or Noble Rock), where the creation of the world and of humans began, according to Jews. It is also believed to be the site where Abraham attempted to sacrifice his son, and as the place where God's divine presence is most greatly manifested, towards which Jews turn during prayer. The site's great significance for Muslims derives from traditions connecting it to the creation of the world and the belief that the Night Journey of Muhammad began from the rock at the center of the structure.

Al-Aqsa, which refers to both the mosque and the compound atop the site, is the second oldest mosque in Islam, and the third holiest site in Islam. The courtyard can host more than 400,000 worshippers, making it one of the largest mosques in the world. The plaza includes the location regarded as where the Islamic prophet Muhammad ascended to heaven.

All of that stands on the Temple Mount, the holiest site in Judaism, where past Jewish temples—the first and the second—are commonly believed to have stood. Orthodox Jewish tradition maintains it is here that the third and final Temple will be built when the Messiah comes.

The Western Wall dates from the period of the Jewish second temple—Jews believe it’s the only part of the temple still standing—and forms part of the retaining wall of the Temple Mount. Because of Temple Mount entry restrictions, the Wall is the holiest place where Jews are permitted to pray, since it’s believed that the destroyed first and second temples were both just beyond, within the hill.8

Around the Temple Mount, we can find Jerusalem’s Old City.

Which is filled with architecture from Jews, Romans, Greeks, Byzantines, Arabs, Ottomans…

In other words: the Temple Mount is the most sacred place in the world for Jews, and since Christianity and Islam both have roots in Judaism, Christians and Muslims had the great idea of building things next to or on top of each other there. Ideal for world peace.

How do you split this inextricably complex area?

Clinton’s high-level solution, which Israelis and Palestinians agreed with, was rather simple: Give what’s most sacred to each group, and maybe keep the rest an open city. For example, the Dome of the Rock, Al-Aqsa Mosque, and Holy Esplanade would go to Palestine, while the Western Wall would go to Israel. The Temple Mount itself (below Al Aqsa) would go to both, and nobody would be able to excavate it without the other’s consent. Both sides saw the merit of this proposal, and explored solutions of internationalizing the area.9

A few years later, in 2009, Ehud Olmert’s proposal would simply put a 2 km2 area including the Old City under international administration.

4. The Right to Return

Despite being an incredibly sensitive topic for both, apparently impossible to solve, this is yet another area where both sides are closer than it appears.

The Palestinian Perspective

According to Palestinians, in 1948, hundreds of thousands of Palestinians were leaving what is today Israel, gearing up for the departure of the Brits. Many of them were expelled by the Jews. When the Brits left and Israel declared its independence, neighboring Arab countries attacked, feeling betrayed by the UK and the United Nations, and trying to correct what they perceived as ethnic cleansing by Jews: 300,000 Arabs had already left before Israel’s declaration of independence. They wanted to make sure no Jewish state emerged there. Alas, Israel won the war, and a total of 750,000 Arab Muslims left and would never be able to come back, in what they call the Nakba.10

Today, these refugees and their descendants amount to 7M people, and Palestinians claim that they should have the right to go back to Israel. The demand is not just about a physical return. It’s also emotional and about honor.

The Israeli Perspective

Israelis claim that a substantial share of the Arabs left of their own volition, or were pushed out by other Arabs.11

They also claim refugees are a normal part of wars. There were 1.5M after WWI, 13M after WWII, and 15M in what’s the most relevant example, the India-Pakistan split and war, where two peoples with two religions—one of them Muslim—simply sorted themselves out according to new borders.

Israelis also point out that refugee numbers usually shrink over time, as they integrate locally. You don’t hear about all the Germans who had to leave what’s today Poland in 1945, or all the Poles who had to leave Russia. Israelis think it’s unheard of that these refugees include people with passports from other countries, people who have never seen the land they claim to own, or people who live in the West Bank or Gaza. It believes it’s bad faith that neighboring countries purposefully keep them as refugees, or that the UN has plenty of agencies that help refugees, but only one focused on a specific refugee crisis—the UNRWA, for Palestinians, and that UNRWA is the only one without a mandate to eliminate the refugee status.12

More importantly, since there are about 7M Jews in Israel and 2M Arabs, if the Palestinians were allowed to go back to Israel, the state wouldn’t be majority Jewish anymore, and it would lose its purpose of defending Jews. Since many Palestinians think Israel should not exist, adding so many of them would threaten the existence of Israeli, and open the door to terrorists in their midst, making the fight against terrorism much harder. So Israel sees no benefit to admitting a substantial number of refugees.

The positions above were still those held by each side at Camp David, but as they kept negotiating afterwards, the Palestinians stated that they recognized the Israelis’ security and demographic concerns:

Even though the Palestinians were not prepared to give up the principle of right of return, they were prepared to talk about practical limitations on how it might be carried out.—Dennis Ross, From Oslo to Camp David to Taba: Setting the Record Straight, via Visions in Collision.

We understand Israel’s demographic concerns and understand that the right of return of Palestinian refugees, a right guaranteed under international law and United Nations Resolution 194, must be implemented in a way that takes into account such concerns.—The Palestinian Vision of Peace, Yasser Arafat, The New York Times, 2002

This became quite concrete in the proposals that Clinton put in his Parameters13:

I sense that the differences are more relating to formulations and less to what will happen on a practical level. I believe that Israel is prepared to acknowledge the moral and material suffering caused to the Palestinian people as a result of the 1948 war. But the Israeli side could not accept any reference to a right of return that would threaten the Jewish character of the state. The solution will have to be consistent with the two-state approach. The guiding principle should be that the Palestinian state would be the focal point for Palestinians who choose to return to the area without ruling out that Israel will accept some of these refugees. I believe that we need to adopt a formulation on the right of return that will make clear that there is no specific right of return to Israel itself but that does not negate the aspiration of the Palestinian people to return to the area. In light of the above, I propose two alternatives:

1- Both sides recognize the right of Palestinian refugees to return to historic Palestine, or,

2- Both sides recognize the right of Palestinian refugees to return to their homeland.

It would list the five possible homes for the refugees:

1- The state of Palestine.

2- Areas in Israel being transferred to Palestine in the land swap.

3- Rehabilitation in host country.

4- Resettlement in third country.

5- Admission to Israel.

The agreement will make clear that the return to the West Bank, Gaza Strip, and areas acquired in the land swap would be the right of all Palestinian refugees, while rehabilitation in host countries, resettlement in third countries and absorption into Israel will depend upon the policies of those countries.

The Taba negotiations went into more detail—for example, Israel mentioned that it would be willing to accept 25,000 refugees in three years; 40,000 in five. They talked about financial settlements and the like. Apparently both sides were converging towards a solution by the end of the negotiations.

Since then, however, these numbers have dwindled. Olmert proposed in 2009 that 5,000 refugees could return to Israel, while Abbas wanted 150,000. Netanyahu wouldn’t approve a single return.

If Camp David was too little, Taba was too late.—Nabil Shaath, Palestinian official

Is Peace Still Possible?

The negotiations between Ehud Barak and Yasser Arafat were down to haggling. There was a broad agreement on land allocation, land swaps, security requirements, East Jerusalem management, and the right to return. Sure, final locations of some settlements were still being debated, as well as the narrative of Israel’s role in the Nakba. But they were so close… Unfortunately, Ehud Barak had lost his legitimacy at home and would be replaced by Ariel Sharon a few weeks later. He didn’t have time or political goodwill to bring this to the finish line.

The negotiations between Ehud Olmert and Mahmoud Abbas around 2009 closed some of the gaps even further, but Olmert had no legitimacy either.14

Since then, the Israeli leadership has not been in favor of a two-state solution.15 The window of opportunity for an agreement along these lines has been closing.

Why didn’t the Palestinian leadership jump on the opportunities at hand? Didn’t they realize the offer was as good as they would ever get? Palestinian positions don’t change quickly. Palestinians only accepted Israel’s existence in 1988, 40 years after the 1948 war. It would take many more years for them to accept the West Bank and Gaza as the basis for a future Palestinian state. It’s as if Palestinian leadership takes so long to internalize the reality on the ground, that by the time it accepts it, Israel has moved on. The result is a persistent gap between the two nations’ positions.

Here’s the silver lining: The Taba negotiations, which offered one of the best deals in a long time to Palestinians, happened during the second Intifada. Maybe in the midst of the horror happening today, Israeli and Palestinian appetite for a peace agreement will emerge again.

In the next article, we’re going to explore what may be the most important question of the conflict: What is the root cause of the conflict between Israel and Palestine?

After studying this for some time now, I’ve realized one thing: No negotiation has addressed the core issue of the conflict. There is one measure I have never seen anybody discuss, and that I think would solve the problem. I will cover it in the next article too.

Further Reading

The Clinton Parameters, Clinton’s detailed outline of a two-state solution.

Moratinos’s Non-Paper summarizing the Taba Negotiations

Visions in Collision, describing in detail the entire process from Camp David to Taba, with insight from insiders.

AND YET SO FAR: A special report.; Quest for Mideast Peace: How and Why It Failed, another, complementary take on the same process.

What Future for Israel, a detailed account of the situation in 2013.

Is Peace Still Possible? A nice website summarizing the four main areas of negotiation between Israel and Palestine.

A Land for All, an interesting alternative approach to the two-state solution, where there are two states, but their citizens can freely move across both.

So which one is it, 8% or 15%? Israelis consider that two pieces of the West Bank are already part of Israel, and don't count them as something Palestinians would be giving up. One of them is East Jerusalem, which Israel incorporated after the 1967 war, and which accounts for 71 km2. The other is an area called “No Man’s Land”, because after the 1948 war, the Israeli and Jordanian forces left this area controlled by neither side. It did not belong to either country for 20 years, until Israel took it over in the Six-Day War of 1967. It accounts for about 46 km2. On top of these two regions, there are the territorial waters of the Dead Sea, which Israel already considers its own, and account for 195 km2. All together, this territory adds up to 312 km2. Without these pieces, the West Bank has 5,538 km2. Keeping 8% of that would be an additional 440 km2 (8% of 5,538). But if you add up the 312 km2 of East Jerusalem, Latrun, and the Dead Sea, that’s 440+312=752 km2, out of 5,850 km2 (the 5,538 plus the 312). 752/5850=13%. This page looks into this.

This source mentions that the Haluza Sands had 72 km2, but quotes this other source, which mentions 72 square miles. This matters, because if it’s in miles, and we use the Israeli basis of 312 km2 they wanted to incorporate into Israel, the swap is 312 km2 for 200 km2, or nearly 1 km2 compensation for every 1.5 km2 taken. Conversely, if you use 72 km2 on a basis of 752 km2, that’s about 1 for 9 km2. Which is to say: in both cases (this and the 8-15%), both sides knew exactly what each other was talking about, but that didn’t matter as much as how much sacrifice each side was making on paper. Utterly depressing that such negotiations fail because of things like that. You can play with this great interactive map to understand the details of the settlements.

I recommend you read them if you’re interested. It’s a pretty short document.

Percentages in this context are always referenced to West Bank surface area. When we say “Israel would give 1-3% of Israeli land”, we don’t mean that literally that, but rather “a surface area equivalent to 1-3% of the West Bank, taken from Israeli land”.

If you want to know the nitty gritty of every agreement and disagreement, please go read that document. Both sides said they represented reality.

It got petty, with exchanges like that sound a lot like they could have been: “The road from Gaza to the West Bank should count as land swap”, “No it should not!”.

Israel’s position was not a range here. The position is unknown, and therefore people have differing speculations on the ask. From here, at p. 183: Ze’ev Schiff, Ha’aretz’s senior military correspondent, claimed that it was twenty-one years; Jerome Slater, an American academic, claimed six to twelve. At Camp David on July 16, 2000, Gilead Sher was quoted as proposing twenty years during which Israel would gradually withdraw from the valley. Charles Enderlin, Shattered Dreams: The Failure of the Peace Process in the Middle East, 1995–2002 (New York: Other Press, 2003), pp. 208, 213.

This is again an example of technicality. Their concerns were things like “Technically, this section of the Western Wall is not as sacred to you, so maybe I should keep it”, or “I get that the Mount of Olives is important to you as an Israeli, but there’s no way I will give up its sovereignty to be international or something like the rest of the Temple Mount.” This makes me so sad. If they really cared about peace, these issues would have been resolved: Just make them international zones.

The Cablegram from the Secretary-General of the League of Arab States to the Secretary-General of the United Nations is a great document to summarize the Arab feeling at the time.

Arabs disagree. My take on this: It looks like the reality is that there were a dozen reasons for the exile, and both sides had a role in it, but I’m guessing that if I were to look into this more in detail, the Jewish role would be pretty sizable.

From Wikipedia: Unlike UNRWA, UNHCR has a specific mandate to assist refugees in eliminating their refugee status by local integration in the current country, resettlement in a third country or repatriation when possible.

If you’re new, know that I edit quotes for simplicity and understanding, while keeping the letter and the spirit as close to the original as possible.

He was down to single-digit approval rates and would soon be replaced by Netanyahu, as well as indicted for corruption. In both cases, it doesn’t look like they had a strong mandate from the Israeli people to sign a peace agreement according to these terms. It sounds to me like they both wanted to sign the peace for many reasons: Because it was the right thing to do, but also because it might have been a political lifeline. Regardless, I actually think a peace agreement will necessarily be unpopular by both sides, so I don’t think this is necessarily bad.

Netanyahu has loomed large all these years, and has publicly backed a two-state solution—as illustrated by the 2009 Bar Ilan speech or the Trump Plan. Some argue that this latter plan is disingenuous though, since his actions have continually undermined a Palestinian state.

My problem with the Peace Agreements is that the conflict isn't something that can be solved with Geography.

The territorial disagreements stem from the way both sides feel about each other. There is a lot of hate and until this emotional conflict is resolved meaningfully nothing will really changes.

But very few policies anywhere on earth focus on how people feel. Its just not the way we're used to thinking.

Rory Sutherland has great videos on influencing people by changing their inner world : https://youtu.be/audakxABYUc?si=1vAZyZX2CvGMOeSy

I found this incredible insightful and thorough--thank you for your work on this, it adds so much detail to the relative sound bites I get from the Times each morning. Is this article part of a series you have plotted out? I see your teaser for the next article and I’m stoked for the one solution that hasn’t seen much discussion yet, but was wondering if you have the total table of contents for this whole Israel/Palestine saga in your Stack?