This post is to help you pick companies, whether for investments or in deciding where to work. This is crucial because proper investments can be the difference between retiring well and early and not retiring at all. As for your job, your success is defined much more by where you work than how well you work.

That said, do not take this article as investment advice. This is just me explaining my thinking. It is only for informational and educational purposes. I am not a financial advisor, and you should not invest based on what I write in this article—or any other article. Please consult with your financial advisor before investing.

The two main inspirations for this post are Ben Thompson’s series on Aggregation Theory and NfX’s series on Network Effects. Both are highly recommended. Check them out if you’d like to go deeper into these topics!

About 70%1 of the value created by tech come from companies like these:

What do they all have in common? Network effects.

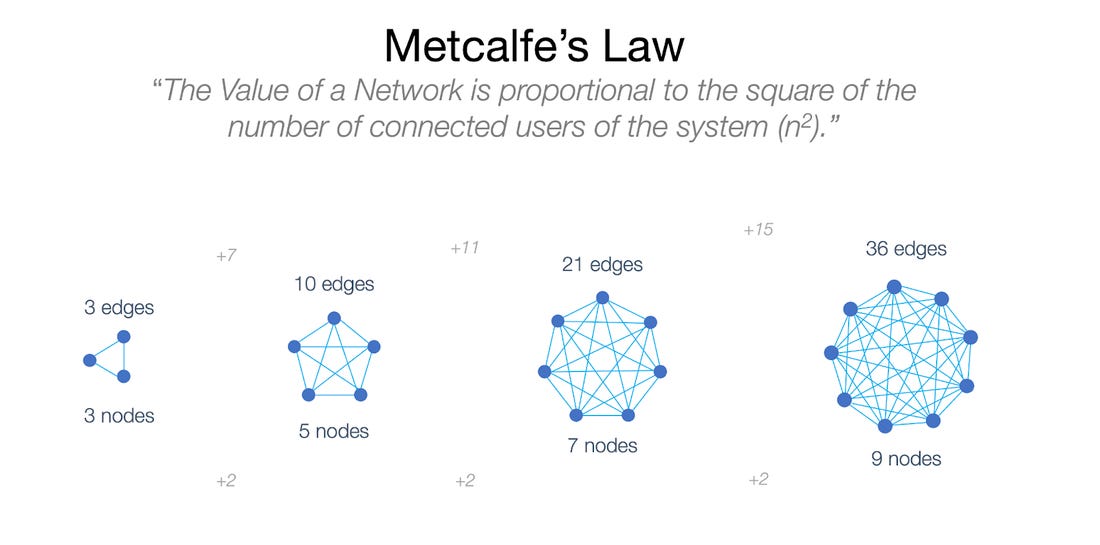

Network effects are defined as when the value of a company’s product or service increases as usage increases.

That means the more users you have, the happier they are, and the cheaper it is to acquire new ones, which means your growth accelerates. Accelerating growth means exponential growth. You want to invest in and work at businesses that grow exponentially. You want businesses that have network effects.

This is not a new phenomenon, however. We’ve known about network effects in business for over a century.

A Brief History of Network Effects

Physical Networks

Before the Internet Era, the physical world also saw network effects. They arrived every time… there was a physical network. Electricity, roads, water, trains, sewage, postal service, natural gas… For example, railroad tracks are much more useful if they can be connected to other tracks. The same is true for all the other network examples. This is why all physical network infrastructure businesses tend towards natural monopolies. This is also why, eventually, most of these industries ended up regulated… Too much control was concentrated in too few hands.

Of all these physical networks, the one with the strongest network effects was the telephone.

As I explained in Should Everybody Learn English?, Theodore Veil, the former chairman of AT&T, said the following in AT&T’s 1908 annual report:

AT&T was discovering that the company kept growing no matter what because each time somebody installed a phone line, everybody else in the network benefited because they could talk with one more person. The more people used AT&T phones, the more valuable the phones were, so the more people wanted them, and the more the company grew.

Why was this type of network more valuable than the other ones mentioned above? There are at least three reasons:

There are global network effects to the telephone: it doesn’t make sense for example to connect the sewage systems of different cities, but it does for communications since you want to be able to talk with everybody in the world. As a result, sewage or water systems tend towards local monopolies, whereas phone systems tend towards global monopolies2.

The marginal cost3 of servicing a phone call is zero. Building the infrastructure is very expensive, which means few will do it. But once it’s built, usage costs barely anything to the company, so all revenue is pure profit.

In communications, subnetworks form within the overarching network. Usually, it’s your friends and family. Once you use a default tool to talk with them, you will keep using it4.

Protocols

The value of a network is based on the fact that every node is interoperable: they can all talk with all the other nodes. For that, they all need to use a single protocol. This means that one protocol will naturally spread to dominate an entire network. Once they do, they are hard to displace.

Internet protocols are a good example. Nobody proposes alternatives to foundational Internet protocols like TCP/IP or HTTP.

This is also why some languages tend to become predominant over others: whenever a network of people is well connected, they need a single protocol to communicate. That’s called a language. The more people interact, the more they need a single language to do so, and the more a main language prevails. This is why English will become the lingua franca of the world.

Knowing the staying power of protocols in networks is why companies fight hard to establish theirs.

For example, Edison and Tesla fought the War of the Currents to get their electricity protocol to win. Edison favored direct current (DC), whereas Tesla favored Alternate Current (AC). Edison knew the stakes were huge, so he went as far as using AC to electrocute animals, including an elephant, to show the dangers of the technology. He lost.

Another example is the war that VHS and Betamax fought for a decade to be the winning videotape protocol: the winner was going to make a lot of money5. And they did: when VHS became the dominant protocol, its maker, JVS, did too. Sony, responsible for Betamax, was left out6.

Network Effects in the Internet Era

The Internet makes network effects possible everywhere. Wherever lots of people want to interact, there’s an opportunity for network effects.

1-to-1 Communication Networks

The obvious application is like phones but for the Internet: communication services like WhatsApp, FaceTime, Facebook Messenger, Line, WeChat, Skype, Zoom… It’s not a coincidence that wherever these communication tools became predominant, it has been very hard for others to displace them.

Social Networks

But 1-to-1 communication is not the only type of communication that’s possible. You can also have 1-to-many networks, where one person can communicate with several other people at once, such as with Facebook, Twitter, SnapChat, TikTok, GitHub…

We typically call these social networks, and they have stronger network effects than 1-to-1 networks. In 1-to-1, you can always decide to switch if the two of you prefer an alternative. Or if your small group prefers one service or another. Sure, you might keep the more widespread 1-to-1 communication tool for a while to keep talking with the rest of the network (as long as it’s cheap or free), but since most of your communications are only with a few people, your switching costs are low. This is why services like Signal, which push for privacy, have gained traction. It’s easy to coordinate small groups to move to them.

But how do you coordinate 400 million Twitter users to move to another network? You can’t. If you want to keep having access to Twitter’s audience, you have to keep going to Twitter. It would take a momentous schism for that to happen, such as what Tiktok is doing to Facebook. Even when this type of schism happens, it’s hard to break apart7. Outside of such events, 1-to-many networks have stronger network effects and tend to maintain their power.

The only way to beat them is if a new social network has such a massive advantage in quality of content and interactions that people start straddling both until the original network dies. This is what happened with all the social networks that came before Facebook, such as Hi5, Jive, or Tuenti. It’s possibly happening now with Facebook with TikTok, and this is one of the reasons why investors are nervous and the stock went down by 30% in the last month.

But there’s only so many of these social networks that can be created. Why? Because the social networks we’re discussing here are “one-sided”: Everybody has an equal footing. Everybody produces and consumes content. There’s only so much content that everybody can create.

Great things are usually made by specialists, not by all of us. These specialists can create things that the rest of us want. This means that networks can emerge with two groups: one that supplies something valuable, and another which consumes that service. This is where the most valuable type of Internet company enters the game: aggregators.

Aggregators

Aggregators put two sides in contact: the supply (the specialists that make something) and the demand (the consumers of the supply).

For example, YouTube is an aggregator. It aggregates user-generated recorded video content for watchers to see. Note how this is different from Twitter, for example, where everybody talks with everybody else.

Netflix is also an aggregator, but of premium video content instead of user-generated.

Netflix aggregates all these shows in one place for you to easily discover them. There are other aggregators of video content, like Twitch, this time for user-generated streaming content8.

You also have TikTok, which is yet another aggregator of video content, like Youtube, but limited to one minute and adapted to mobile.

And that’s just video. Outside of that, there are hundreds of other aggregators. Google aggregates all the websites of the world to make them easily accessible.

And so on and so forth:

Marketplaces

As you can see, some aggregators are marketplaces, like Uber or Airbnb. These are called 2-sided marketplaces: the supply and demand meet and there’s a financial transaction between them.

Sometimes, marketplaces can be 3-sided. For example, in Doordash/Deliveroo/Uber Eats, you have consumers who pay for food delivered to them. They do so to both restaurants and drivers. There is a financial transaction between consumers, restaurants, and drivers.

But some aggregators are not marketplaces. Is Google a marketplace? Is Facebook? No. In these instances, there is no financial transaction between the supply and the demand of the content.

The brilliance of Facebook was to realize that the content made by your friends was only going to take them so far. They needed professionals to create better content. That’s why they opened up the platform to external developers, who created first videogames and horoscopes, and later posted articles to the network. It moved from a simple social network to adding an additional aggregation layer: where specialized suppliers added specialized content.

And to monetize that, both Google and Facebook added advertisers. So in reality they aggregate three sides. On Facebook:

Content makers like newspapers (content supply) bring the quality content expecting in exchange clicks to visit their sites and monetize through ads or subscriptions.

Consumers (content demand) go to the site to consume that content. Some of them can also become content supply some of the time.

Advertisers take advantage of that content demand and try to channel it into visits to their own sites to sell stuff. From their angle, consumers are supply (of attention), and they are the demand of that attention. They buy that attention through ads. That’s the magic of ads aggregators: they turn content demand into attention supply.

If you think about it, Google is basically the same:

Supply is web pages. A lot of them include amateur content.

Demand is searchers.

Advertisers take advantage of the demand for web pages, and place ads to channel some of it to their own sites to sell stuff. Consumers are supply of attention for them, advertisers are the demand for that attention.

Whether these are 2-sided or 3-sided aggregators, why are they so special?

When there are millions of suppliers and potential customers, it’s very hard for them to meet. For example, how would you know which car owners would be willing to drive you somewhere? How would you agree on a price with them? Uber aggregates drivers for riders so they can easily interact.

Once a lot of supply is in one place, all the demand goes there because it’s much more convenient to discover that supply. Once the demand is in that aggregator, additional supply goes there because otherwise they miss out on potential business. More supply means more demand, more demand means more supply. They grow organically and exponentially together. Network effects.

Once aggregators are established, they’re hard to displace: you would need to coordinate millions of suppliers and demanders9 to move at once. Take Airbnb, for example. You know the company offers a lot of places to stay around the world. So you go to airbnb.com to find one. Owners of the rentals know this, so they put their properties on Airbnb. Maybe initially they put their rentals on a few different websites, but after a while, they stopped: why would they do that, when most of the demand comes from Airbnb? And it’s a hassle to have a rental across sites: when you get a booking from one site, you need to eliminate the availability on the other sites. Too complicated. Too much work for little benefit since most rentals come from Airbnb anyway. So you stop using alternative booking sites and give all your business to Airbnb.

These network effects are what underpin the growth of aggregators. But aggregators do something else: they don’t give away the direct relationship to the customer. They stay as intermediaries. This gives them a massive amount of power, because to access demand, the suppliers need to adapt to the aggregators’ asks.

Take Google, for example: there’s an entire industry called SEO (Search Engine Optimization) that focuses on optimizing websites for Google. Think about it: suppliers (website owners) pay to get access to make their content accessible through Google. The same is true for Youtube, for example. Meanwhile, Twitch takes 50% of the revenue generated by streamers. Do you think streamers pay that ransom willingly? No. They do it because they have no other option: to access viewers, they must stream on Twitch, that’s where they are. And to do that, they must fork out their money.

This dynamic is why so many aggregators become behemoths. Nearly all the companies in this image are aggregators. Can you tell which ones aren’t, actually?

On Facebook, an advertiser or a page owner can’t get your email address.

On Youtube, you can subscribe to a YouTube channel, but you go see the next video from that channel on YouTube: the channel doesn’t get a direct contact channel with the viewer. Which is why when YouTube cancels some people’s channel, they freak out.

On Uber, you’re not supposed to get a driver’s phone. Even if you get it, it’s not going to be that useful because the driver might not be available when you need him. So Uber still owns the relationship with the demand, which gives them all the power in the network.

Compare these to tech companies that are not aggregators, such as companies that create physical products and sell them directly to consumers over the Internet (called “DTC” companies, for direct to consumer).

The Plight of DTC

I picked the first four DTC companies I could think of: Warby Parker, Allbirds, Blue Apron, and Casper.

Warby Parker is down 40% since its IPO10.

Allbirds is down over 50% since its IPO.

Blue Apron is down 94% since its IPO.

Casper was down 70% from its IPO price until an offer from a Private Equity firm delisted it11.

Why? Because these businesses don’t have network effects.

Online, your competition is global. If you’re successful, a hundred other companies will spring up to snatch some of your profits. If your company doesn’t have any defense, it will be eaten alive.

Traditionally, a good brand and a good product were good enough for you to thrive. The better the product was, the more money it made, which it could spend on marketing, which would increase awareness. Additionally, brands like this have some network effect: word of mouth. The more people have something, the more they talk about it, so the more people hear it, and the more people start using it. But that’s a weak network effect.

And when you have 7 billion people looking at opportunities to make money, some of them will figure out a way to copy what you do well, and then do it for cheaper.

So DTC brands have a triple whammy of obstacles. The bigger your DTC brand is:

The less valuable each new customer is, because the most valuable ones discovered you first12.

The more expensive each new customer is, because you need to go find them in places that are less and less obvious13.

The more competition you have, because more people notice your success and copy it.

You might think: what about economies of scale, when a company reduces costs when it becomes bigger? It’s true. Sometimes, the bigger, the cheaper it is to produce things. This is why car makers or chip makers tend to be big companies. The key for economies of scale to matter is when the majority of the costs come from production instead of things like marketing or distribution. In things like mattresses or sunglasses, the biggest cost is not production, it’s marketing and distribution. And there’s only so much you can optimize your production costs.

This naturally caps the growth of any DTC brand. Their network effects and economies of scale are not strong enough to counterbalance the diseconomies of scale.

This DTC dynamic is valid for many other businesses too. For example, take Robinhood, the online brokerage. They were ground-breaking because they introduced virtually14 free stock market trades. They also have some economies of scale because the more customers they get, the more money they make, and the more they can spend creating great features. But those features can be copied by others. That’s why there were hundreds of brokerages before Robinhood, and there will be dozens after it. It doesn’t have network effects. Sure enough, Robinhood’s stock is 2/3 down since it IPOed.

It’s also why I’m bullish on crypto, but I’m not bullish on companies like Coinbase. While they are amazing at what they do, there are no massive network effects there. They were first and built a great product, but they don’t have an inherent moat that protects them from every other crypto exchange out there. They are exposed to all kinds of competition.

“All happy companies are different: Each one earns a monopoly by solving a unique problem. All failed companies are the same: They failed to escape competition.”—Peter Thiel, Competition Is for Losers.

Competition is great for the economy and for consumers, but it’s bad for making money as a business.

By connecting the entire world, the Internet is amazing at increasing competition, which is amazing for consumers. New products are created constantly, and new companies appear to make them cheaper, reducing prices for consumers.

These are horrible businesses to invest in or work for, though. That’s why network effects are so important for Internet businesses, and hence why aggregators are so successful.

Power Dynamics of Aggregators

Aggregators are interesting because they’re amazing businesses and they’re great for consumers: people love the services from Google or the amazing content of TikTok and Youtube. As Google loves to say, customers are only one click away, and the only reason people come back is because Google is simply better.

Unfortunately, one of the players of the aggregator game is usually the loser: the supplier.

Who has complained the most about Google? Companies like Yelp (supplier of business pages and reviews) or news outlets (suppliers of news content). Who complains about Facebook? Again, news outlets. Who complains about Uber? Drivers more than customers. Putting all the supply on an equal footing makes it much harder for suppliers to differentiate themselves in the eyes of the demand. It creates hypercompetition at the supply level.

Unsurprisingly, creators of supply for aggregators frequently suffer from mental health issues. A simple Google search (ahem) will lead you to mental health problems for Youtubers, TikTokers, Twitch Streamers… Talk with blog owners who lost most of their business overnight due to an algorithm change from Google. Or consider developers for Facebook, who have died overnight when Facebook has changed its policies.

Interestingly, this dynamic is exactly what US law wants: a hypercompetitive market that is amazing for consumers. That’s why the US government has had such a hard time regulating aggregators. They realize something is askew, but the end result is great for consumers, and in the US the definition of monopolies depends on whether consumers are better off. With aggregators, they usually are (or people would just go a click away to the competition), so there’s seldom a strong anti-competitive case15.

Is there an alternative where everybody is happy?

Platforms

Platforms also put together supply and demand, but with a massive difference: they don’t prevent them from getting in touch with each other.

Microsoft Windows is the most famous platform, where you had developers of software that used Windows to sell their software to consumers. Bill Gates always defended the importance of making an ecosystem that worked for everybody, developers of software for Windows as well as Windows users.

Another example would be LinkedIn, where you are the supplier of your own resume and career, and recruiters are the demand. If a recruiter wants to talk with you, she can. She will need to pay for the service, but she can then form a relationship with you that can continue beyond the site.

Crucially, sometimes platforms can replace aggregators.

This is what Shopify is doing with Amazon. Amazon aggregates all sorts of consumer goods in one place and makes it very easy for consumers to find them. To make sure their customers’ experience is amazing, the company takes care of everything, from digital experience to payments and even storage and shipping of the goods. You never interact with the brand, which is why they sometimes put inserts in the products giving you freebies if you give them your email or “register the product”.

Shopify has a completely different approach. It gives tools to brands so that they can easily set up their own ecommerce shop. Everything that’s hard to do in that business, Shopify simplifies, from website building to payments to shipping. But you don’t see Shopify in your day-to-day Internet browsing because the company doesn’t want to own that relationship. Quite the opposite: they want brands to focus on their products, their marketing, and their customer experience, to really differentiate themselves against the cookie cutter experience offered by Amazon. You can say Shopify is the anti-Amazon16.

As you know, Ankorstore, the company I work with today, is another example of a platform that is fighting against Amazon: it helps brands get in touch with retailers so they sell their products to end consumers. The company doesn’t prevent that relationship from forming: it facilitates such a relationship.

I also work with another platform that is replacing an aggregator. You’re using it right now: Substack, replacing aggregators like Medium.

Substack vs. Medium

Back when I wrote my first COVID pieces, I wrote them on Medium for free. If I had put them behind the paywall, the 60 million views my articles got could have netted me up to $500k17. But I didn’t do it for that. I did it to help people during a public health crisis.

In order to keep having a maximum impact, I put a form to gather emails at the bottom of the articles a few weeks after starting. Medium didn’t like it and asked me to remove them, but they didn’t take measures given the COVID emergency. That’s the only reason why most of you are reading this now. I was going against their terms of service.

Once I gathered a sizable audience, I set up MailChimp to send you my articles. For months, I spent hundreds of dollars a month to send these emails—a reasonable amount of money for me, especially given that I was just trying to help.

But one day, I heard that a new company called Substack was allowing anybody to send emails to their audiences for free. And they had a crucial benefit: the relationship with the customer was with me, not with Substack. The email list was mine. So was the payments relationship18. So I moved to Substack.

Many of you have asked me about this: how does Substack work? What’s their business model? Where do you see them going in the coming years? Why do they offer advances to writers? Why wouldn’t they move out of Substack once their exclusives lapse? I will answer all these questions in an upcoming premium article: The Future of Substack.

Takeaways

“Software is eating the world.”—Marc Andreessen.

The future of the global economy passes through the Internet.

But the Internet is extremely competitive.

And competition is good for consumers but bad for business.

So as an investor or worker, you want to invest in companies that do not have competition.

The best ones are those with network effects, which make them grow fast and create a moat that’s hard to beat.

Aggregators are the best example of network effects: they aggregate supply and demand in one place, make the experience amazing for the demand, and squeeze suppliers from all their market power. They are ideal companies to work at or invest in. That’s why Facebook and Google employees tend to live cozy lives and make so much money. It’s why their stock has been such a great investment. Any aggregator, in general, tends to be a good investment.

Aggregators are not the only option though. An alternative is Platforms. Sure, their network effects are weaker, but they’re strong enough to grow fast, and to last. That’s why Shopify has been an amazing investment, and why I work at Ankorstore.

In other words: try to work at or invest in aggregators and platforms19.

And if you are a regulator, what should you do about aggregators? There’s a very simple solution to them. I will cover it in a future article of this series, which will include:

Why you need to understand aggregators to understand the polemic with Joe Rogan

Besides Network Effects, the other type of company that can also succeed on the Internet.

The Future of Substack

How to Regulate Aggregators

What is the playbook that Internet Network Effect Businesses use to grow?

Flywheels for Network Effect Businesses

Subscribe to access!

From the NFx blog, which is amazing. They looked at all the tech unicorns (companies with over $1B in valuation) minted between 1994 and 2017. Of the 336 unicorns, 35% grew mainly through network effects, and accounted for 70% of the overall value generated.

They were only limited by regulations, which is why national monopolies emerged across the world.

Cost of adding more one item.

This makes the value of such a network more valuable than what Metcalfe’s Law predicts, and instead follows Reed’s Law.

VHS had less definition and poorer sound, but originally you could record an entire movie in it, while in Betamax you could only record 1h. By the time Betamax expanded to 2h, it was already smaller than VHS, and given network effects, it was impossible to compete. Also, VHS was more thoughtful about a network approach: JVS licensed VHS to anybody who wanted to build for it, resulting in more competition, more marketing, and more sales than Sony’s Betamax, which was owned by one single company who didn’t have any urgency to compete.

One of the side-effects of protocol networks is that they slow down innovation. If they have a single owner, there is no incentive to change the protocol that makes them so much money. And when there is no owner, it’s very hard to coordinate millions of users to agree on the next protocol.

Here, the network is of sellers of videotape readers, videotape makers, and consumers. Three sides that needed to coordinate.

Like when members of the Republican Party in the US threatened to move from Twitter to Parler en masse. These things only tend to happen when the new tool is an order of magnitude better, not just a bit better.

YouTube also does streaming, to combat Twitch. And by some measures, it does more.

Another word that needs coining. So here we are. I’m going to start keeping track of the words I coin.

Initial Public Offering. When a company goes to the stock exchange to trade their stock.

And I wrote this before the crash in tech stocks…

We say LTR goes down with scale, where LTR stands for LifeTime Revenue. Others use LTV for Lifetime Value, but this is a misnomer, since LTV accounts for CAC. It’s complicated. I’ve written about this in the past.

We say CAC goes up with scale, where CAC stands for Customer Acquisition Cost

You pay a few basis points (hundreds of percentage points) each time because they sell your purchase / sale orders to hedge funds, who then “front” your purchase: they buy it before you and sell it when you buy it, so they can make a microamount of money each time. If you’re interested in learning more about this, it’s called “order flow”.

The exceptions appear when aggregators blatantly exploit their power in a way that makes it worse for consumers, such as the App Store forcing payments through Apple and their 30% cut (which reduces alternative payment systems and takes such a heavy tax that many businesses are simply not viable because of it), or when Google sends searchers to worse results pages because it gives an advantage to its own results, like what happened with Google Shopping.

These platforms are not always great businesses. In some cases, putting in contact the supply and demand disintermediates the platform: they stop dealing with each other directly. This is why for example companies like Thumbtack have a hard time growing. This company puts in contact service people with consumers (think for example a handyman/handyperson). But think about that handyperson coming to your home and doing a good job. What will they do at the end? Give you their card so you can contact them directly and disintermediate Thumbtack.

I did back-of-the-envelope calculations based on previous articles that I had published behind a paywall on Medium. I assumed that the same dollars per impression would have worked with 60 million views, and that no views would have been lost due to being behind the paywall. Medium’s paywall is special in that you can read up to 3 articles for free, so it was not inconceivable that most of that demand could have been maintained despite the paywall. But I didn’t want to risk it.

If you are a premium subscriber, every month / year you see in your bank account Uncharted Territories, not Substack.

Investing is always a balance between the current price and the value. My insight here is that, generally, the market doesn’t account for the true value of network effects when it bets on companies. As a result, it tends to underestimate the potential of aggregators and platforms, and overestimates the value of businesses that don’t have network effects. But this is a rule of thumb, it doesn’t mean it’s true of all aggregators and platforms. Again, please don’t invest based on this article. This is for informational and entertainment purposes, not investment advice.

I have a problem with one part of your article, here:

"Interestingly, this dynamic is exactly what US law wants: a hypercompetitive market that is amazing for consumers. That’s why the US government has had such a hard time regulating aggregators. They realize something is askew, but the end result is great for consumers, and in the US the definition of monopolies depends on whether consumers are better off. "

This is true, and indeed the law as currently formulated focuses only on monopolies that are demonstrably bad for consumers. The issue is that the market power that makes Facebook and Google great investments is also the market power that they 1) wield against competition on their platforms and 2) abuse in ways that damage society. There are stronger protections against both in Europe, which is why Facebook is in such trouble there. But it is evident here in the damage Facebook does to society in pursuing the profit motive exclusively and amorally.

I went to Stanford and many of my closest friends there are in tech or VCs. I did work in the field myself, but I am a management consultant now, and some of my projects have been with companies at the very frontier of cyber. These issues are blind spots for my friends, and there's definitely a solipsistic and libertarian strain in Silicon Valley. But these are issues that society and the law will have to wrestle with, because it's crushing the middle class and destabilizing democracy. Some is starting to happen with things like the growing traction of trends like ESG and stakeholder capitalism, but society moves much slower than tech, and I fear we will not put a cap on it before we lose the formula for what is important - our people, rather than solely our profits.

By the way, I am very much a capitalist. But I have seen too much having lived in the tech world for decades of the unbridled, but amoral enthusiasm for the "next great business model" without a pause to consider the damage that's being done. I am against a heavy hand from the government, but "power corrupts" has never seemed more true than today with the rise of global, unaccountable elites. Capitalism is absolutely the best system at it's core, but there are absolutely market failures, and they have never been more consequential than today.

This is a lovely article.

It demands a measured and considered response.

I will try to do that here.

The first thing is some points about network effects are inaccurate.

Metcalfe's law is kind of true mathematically but is untrue realistically.

That's because every new member is not valuable to the entire network: no one's social circle has that sort of range.

So, even if I could talk with 4 million people on the telephone, I certainly don't want to talk with even a fraction of them: possibility is not the same as demand.

Even mathematically, the law is suspect. The growth in value should really be N² - N rather than N² since each node can't communicate with itself.

I'm surprised as to how very few people point either of these out.

Two, network effects are a very successful business model whose time, I suspect, will soon begin to set under the sun.

The reason is because platforms and to a lesser extent, aggregators, give up vertical control for the benefits of controlling supply and demand in one place.

The problems are twofold: one, it only works if there's a massive pool of supply, like with information (Google) or social relationships(Meta) or applications( Apple app stores). Uber and Airbnb, companies already dealing in huge markets, owe a considerable part of their success to creating new sources of supply: many people who had not drove a cab or put their apartment up for rent in their lives began to do so.

This is why it's difficult to have a platform business with carwashing or massages or something similar: both the demand and supply aren't high enough to make the marketplace truly liquid.

The second problem is the issue of vertical control. If you give up vertical control, you allow some bad eggs onto the platform. There's no other option.

That's fine when the bad egg is just a troll or an ideologue.

With other industries, it's different.

Industries like healthcare cannot be truly network-scalable because of this problem. And also because these are not one to many networks either, e.g a doctor can't treat thousands at once.

Network effects are great at transactions. They are not great at relationships.

So relationship businesses like law and accounting have remained fairly impervious to software's world-sized appetite.

Three, aggregators are kind of a patch. Aggregators bring the relationships back. That's what they do: bringing back the relationship with the writer ( Substack), the relationship with the retailer( Shopify), etc.

And so, they represent a sort of evolution.

I would add Stripe to this list too.

The companies of this decade and the next are going to be the ones who provide empowerment: those who own the infrastructure of the new relationships of the digital economy.

And on this, Tomas, as usual, is spot-on.

I look forward to seeing the related posts on these matters.