Why Is Texas Mainly a Triangle?

My first Business Communication & Storytelling Course will sell out. I think I’m going to limit it to 50 students to review each student’s content. I only have 7 spots left. I don’t know yet if I’ll give another one. To enrol, pay here. For more details, read here.

Today, we’re going to understand Texas. In this week’s premium article, we’re going to do the same with Atlanta. Both are quite counter-intuitive and help us understand why cities succeed in some places and not others. Subscribe to receive the premium articles.

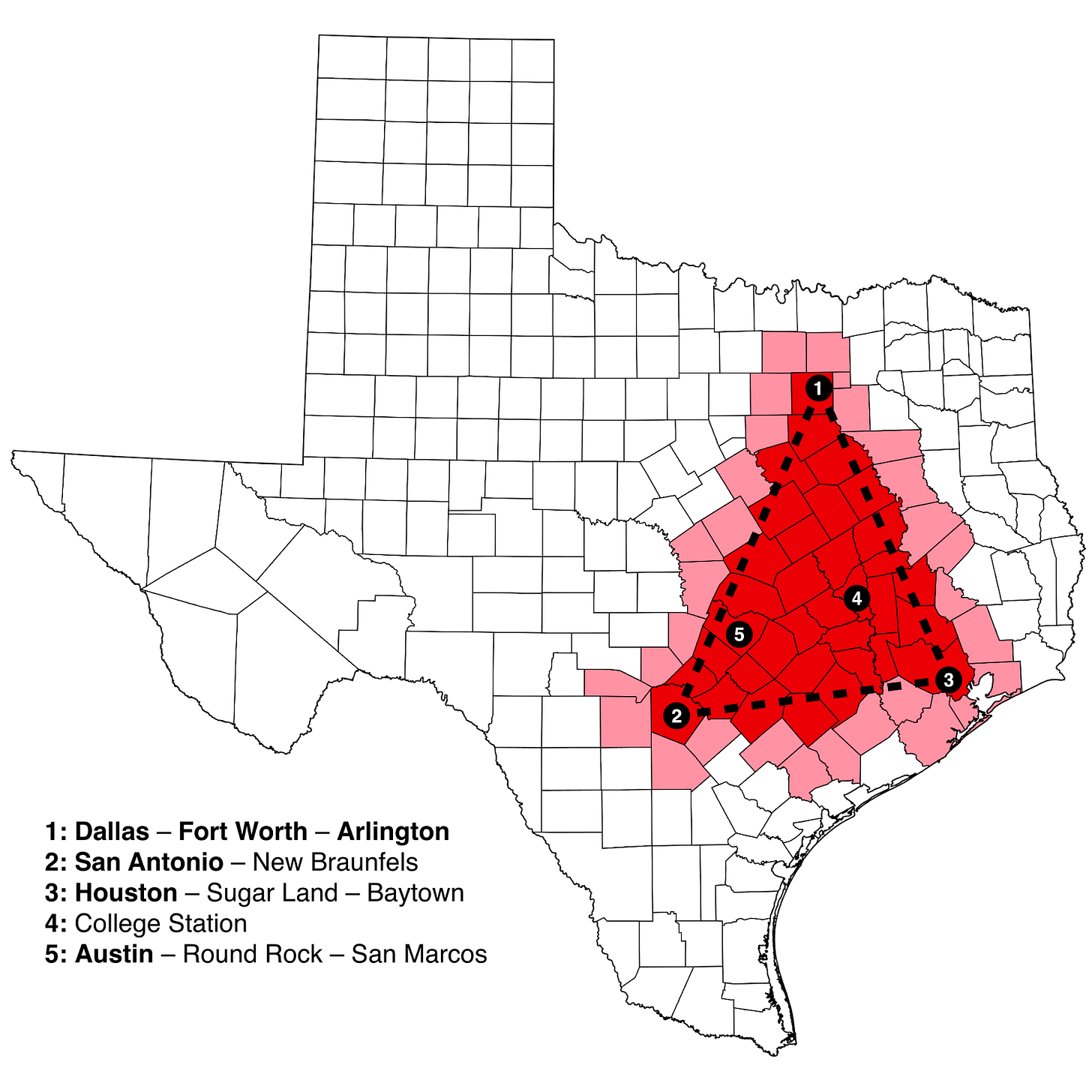

Have you ever heard about the concept of the Texas triangle? It’s the triangle formed by Dallas, Houston, and San Antonio, and it concentrates the vast majority of Texan population. But why is there a triangle? Is it really a triangle?

To understand this, we need to start with another conundrum: Why is Dallas not a single city, but a metropolitan region that includes another city, Fort Worth?

Dallas – Fort Worth

Normally, big distances separate cities from each other. The bigger the city, the bigger the distance.

Why? Because cities are where trade happens, and trade has network effects. The bigger the city, the more customers, the more trade will be attracted by these customers, and the more businesses will move there, followed by workers, and more customers. Big cities absorb all the potential business from their surroundings.

But not in Dallas–Fort Worth! Both of these cities were big and kept growing until they merged. Why?

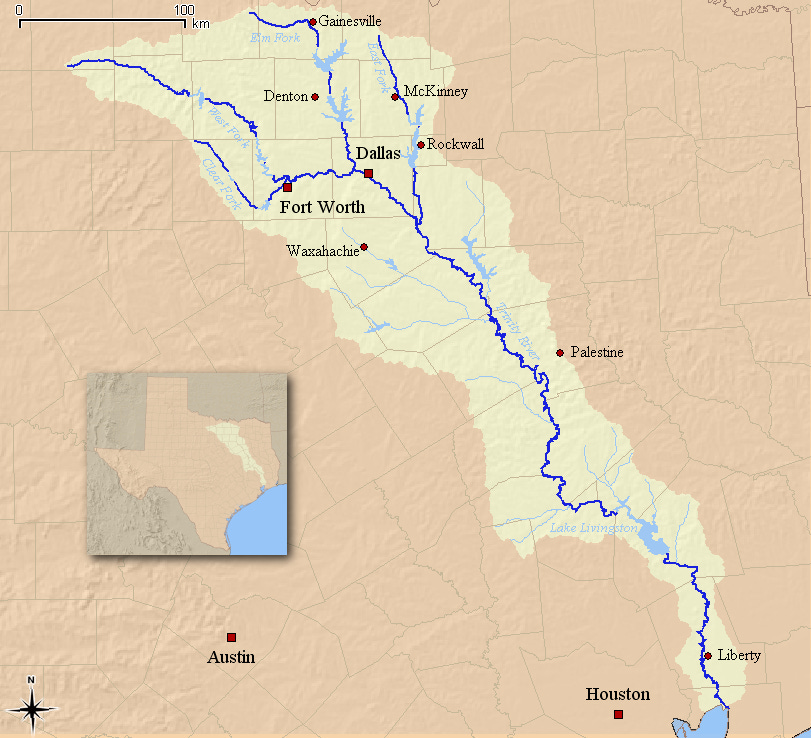

They are on the Trinity River:

Why are there two cities on the same river, just a few miles away from each other?

Dallas and Fort Worth are each at the confluence of the Trinity River with different tributaries. Is this why they grew independently, despite a small distance between them? Maybe they became trade nodes between their tributaries and the Trinity River? Indeed, a key point of river confluences is their ability to act as markets for all the river branches. But this assumes they’re navigable. These ones were not:

Beginning around 1836 numerous packet boats steamed up the Trinity River, bringing groceries and dry goods and carrying down cotton, sugar, cowhides, and deerskins. In 1854, one reached Porter's Bluff, forty miles below Dallas. Often, however, their movements were impeded by snags, sandbars, low water, and other hazards.

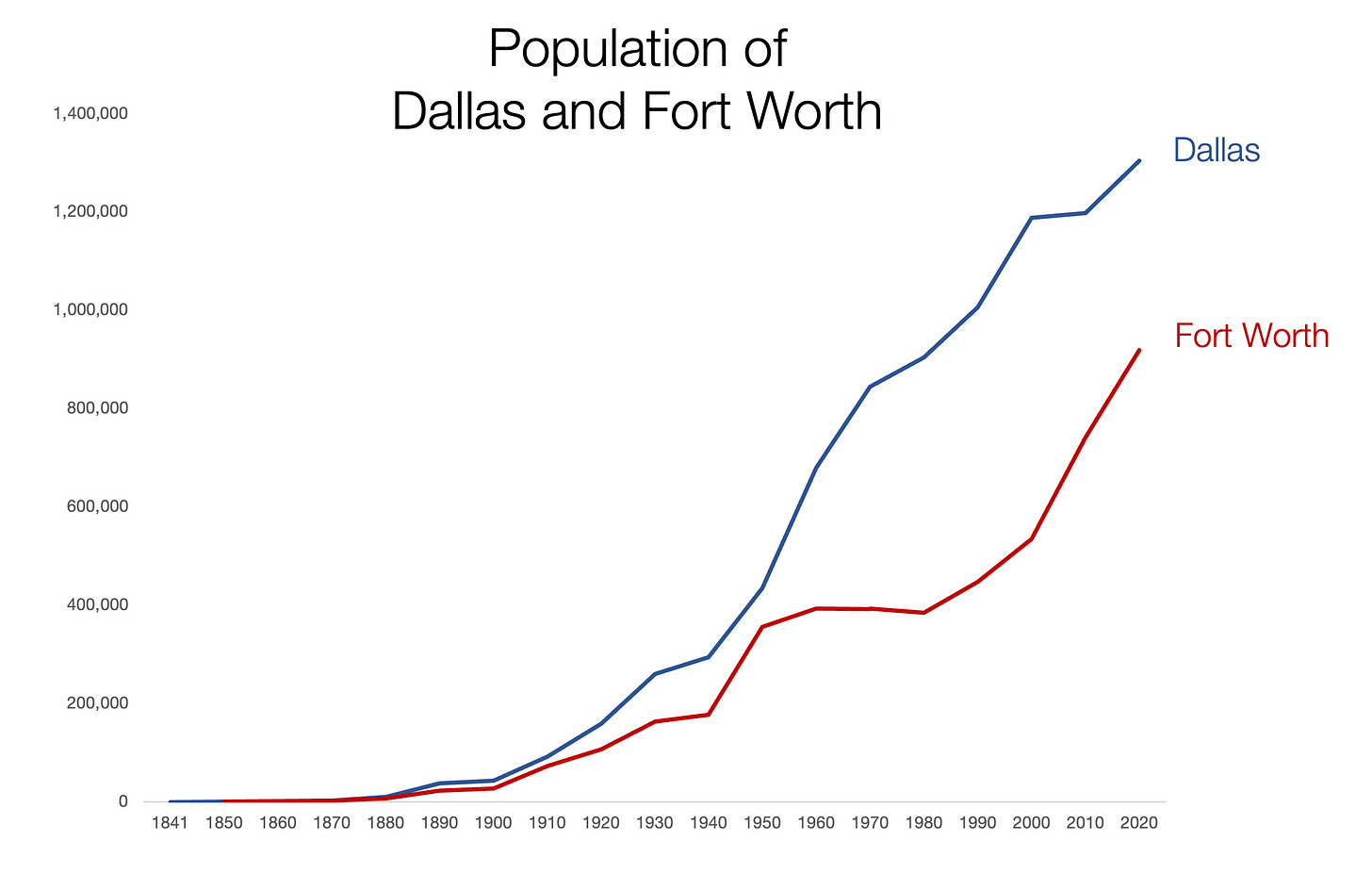

And that explains why Dallas and Fort Worth didn’t grow very fast early on:

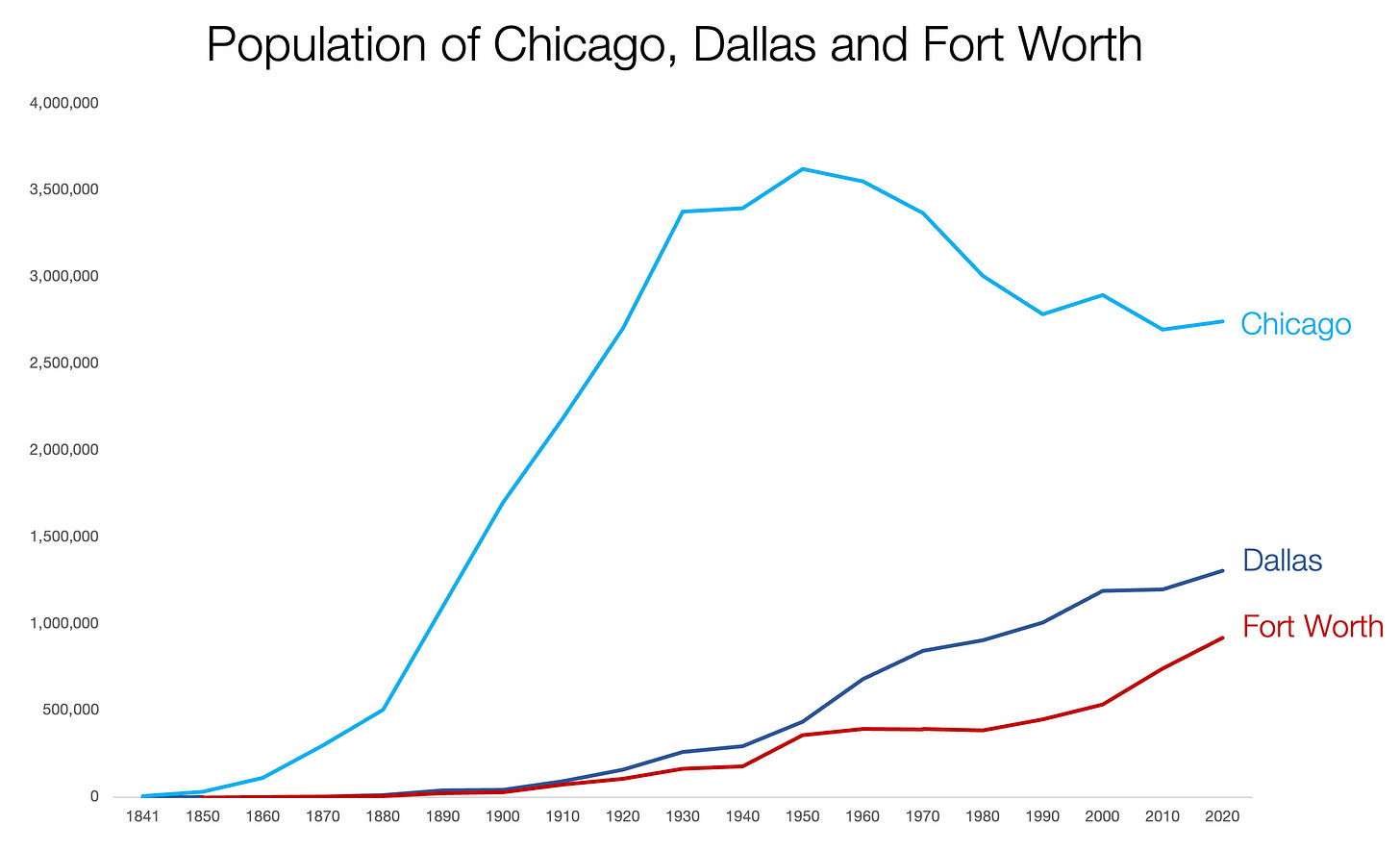

It took up to the end of the 19th century for them to start growing, and they only took off in the early 20th century. To give you a sense of how Chicago was growing at the time:

So the Dallas–Fort Worth story is one that starts in the early 20th century, which makes sense given their rivers were not easily navigable: The distance might have been short in miles (40 mi), but not in time. It took a long time to go from one to the other, which made their parallel growth more reasonable.

Why did they grow despite not being on a navigable river then? Let’s look at each one.

Fort Worth

It was founded in 1849, just after the Mexican-American war, as the westernmost fort on the US frontier. It soon became a settlement, and soon after that earned the nickname “Cowtown”. Why? Because the Chisholm Cattle Trail ran through it.

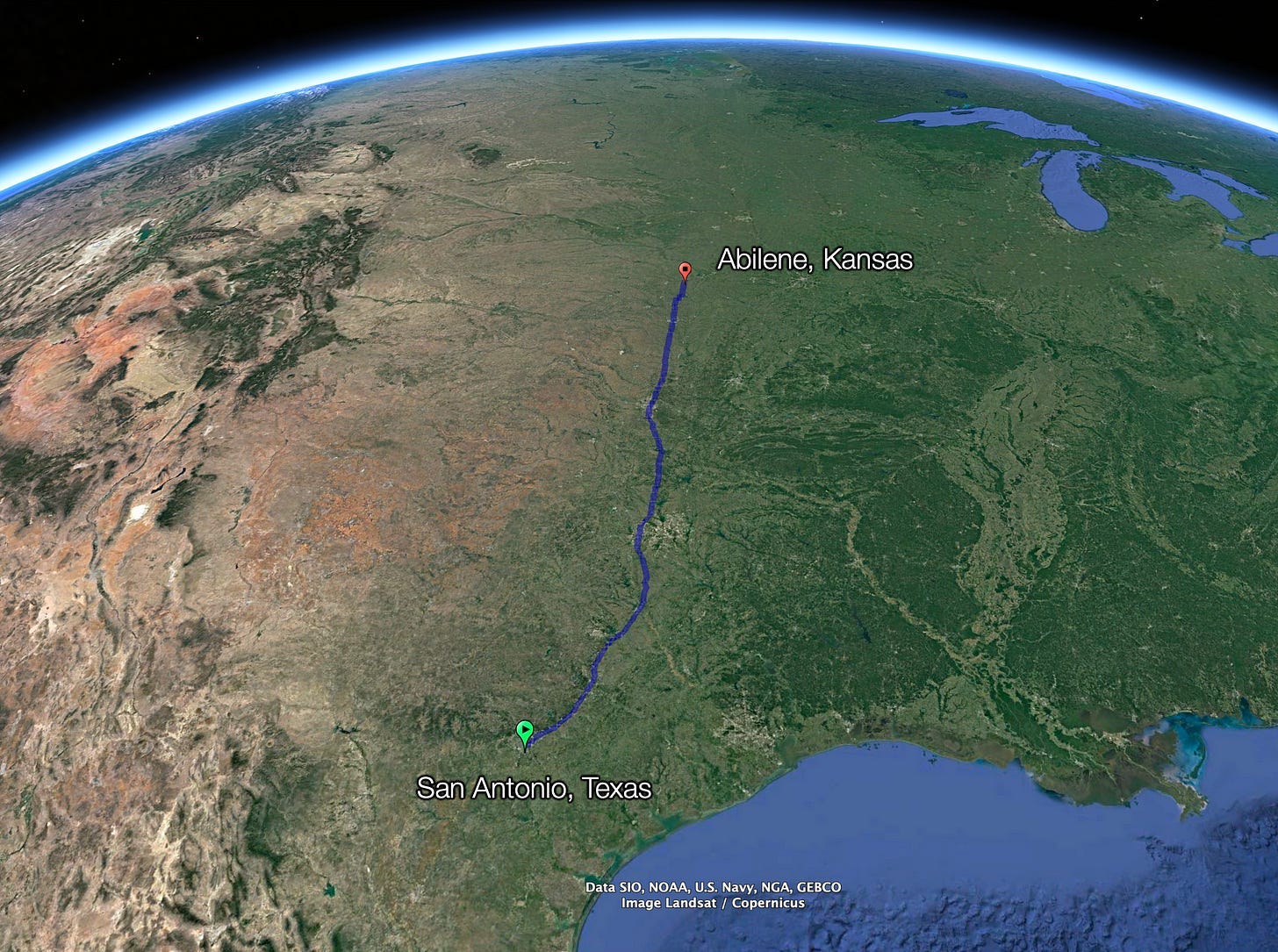

It’s unclear where that trail was, but it was probably something along this line:

But if you zoom into that trail, what do you see?

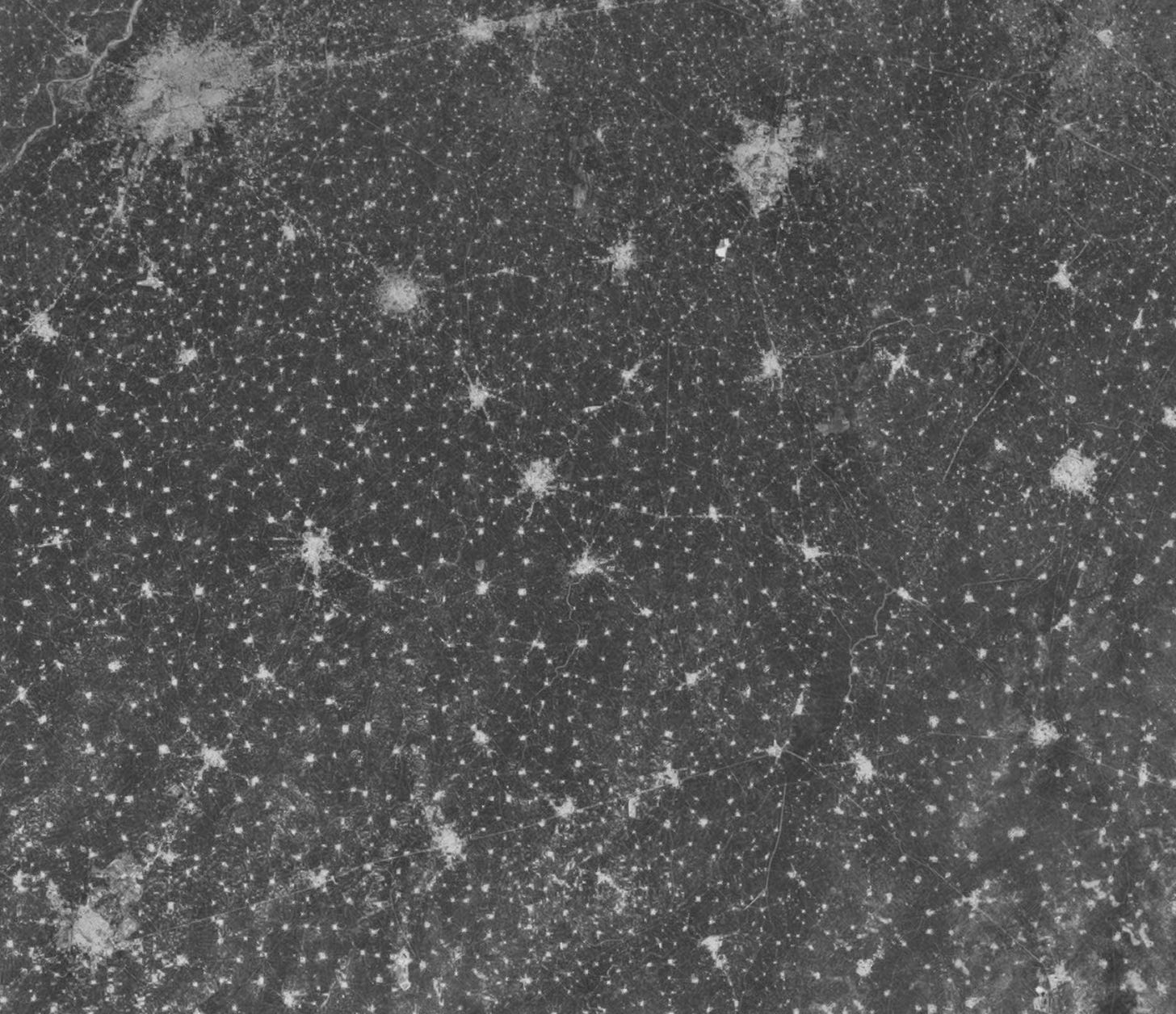

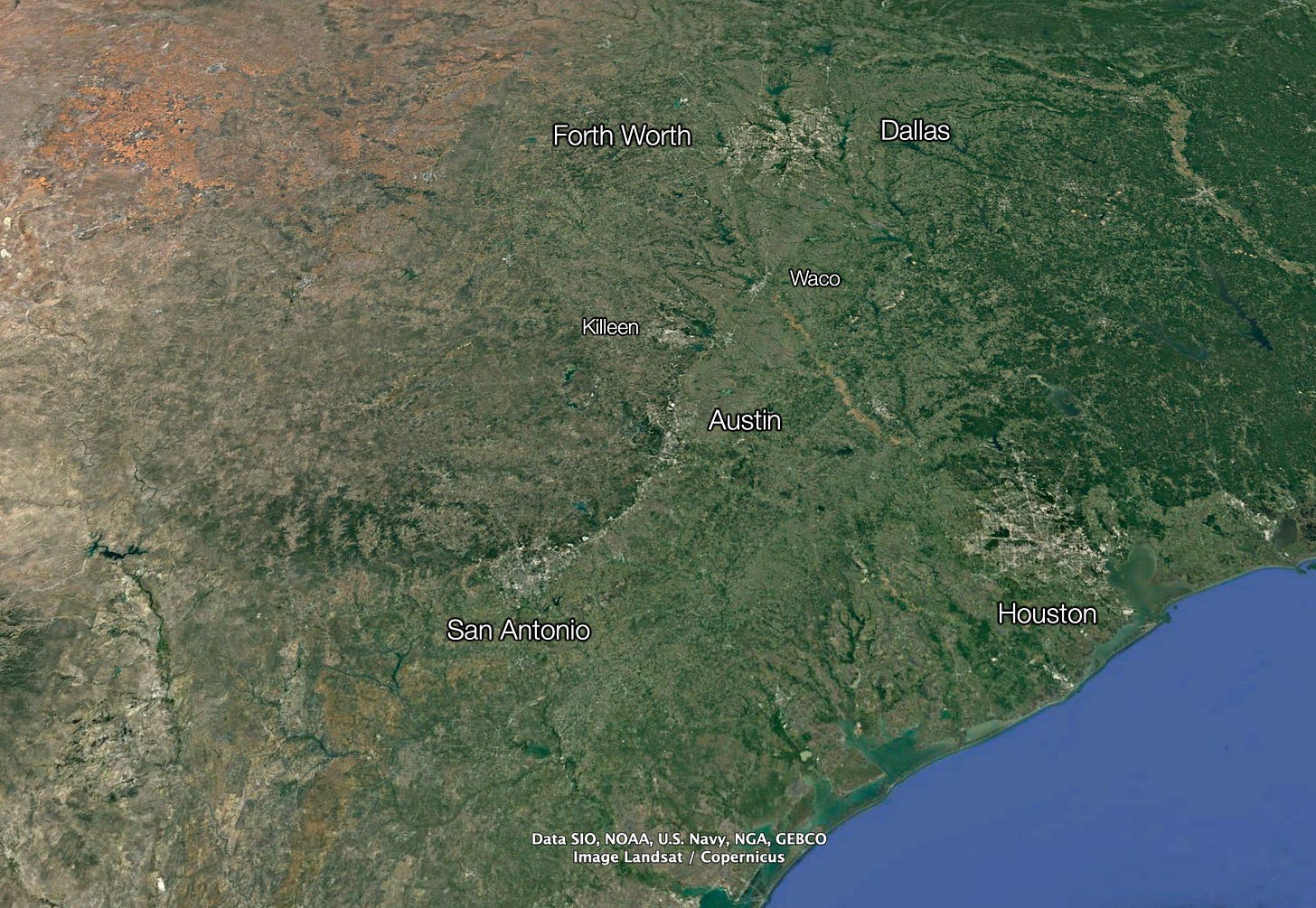

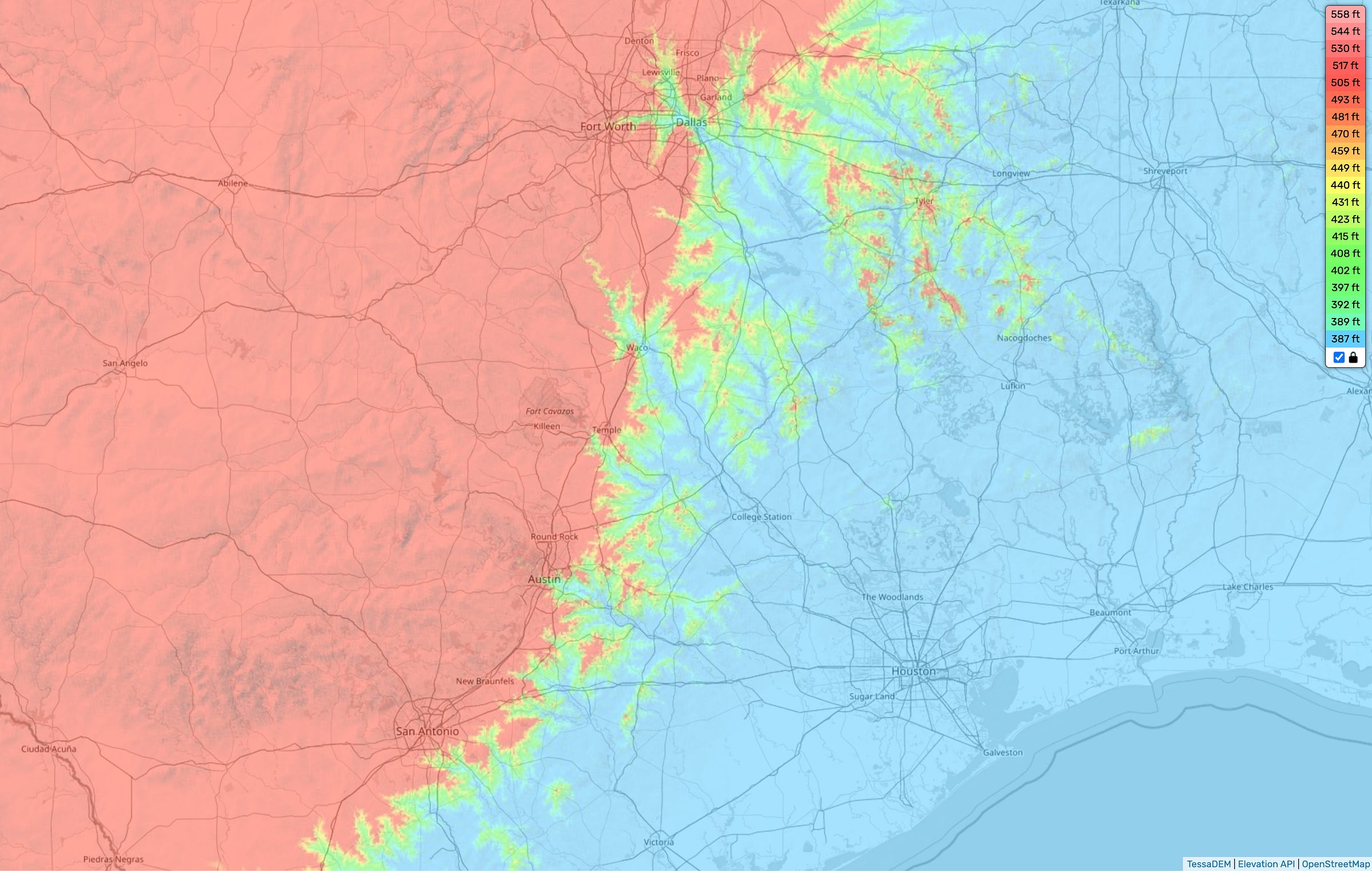

Satellite maps show parallel green (left) and grey (right) lines between San Antonio and Dallas today, which correspond to vegetation and urbanization. Why? Let’s look at the topography of Texas:

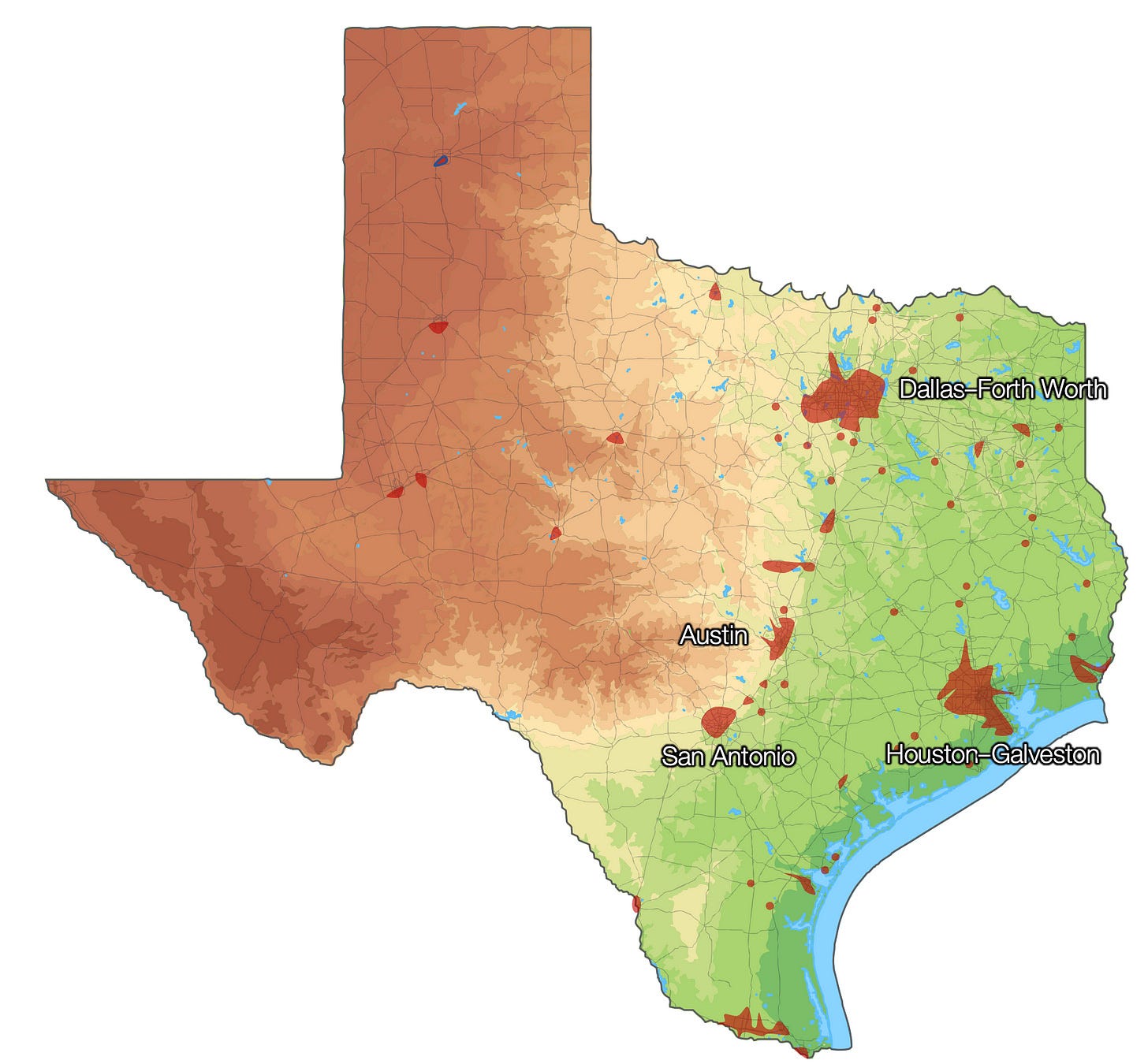

Let’s zoom in to the Texas Triangle.

If you zoom in further and focus on the fall line:

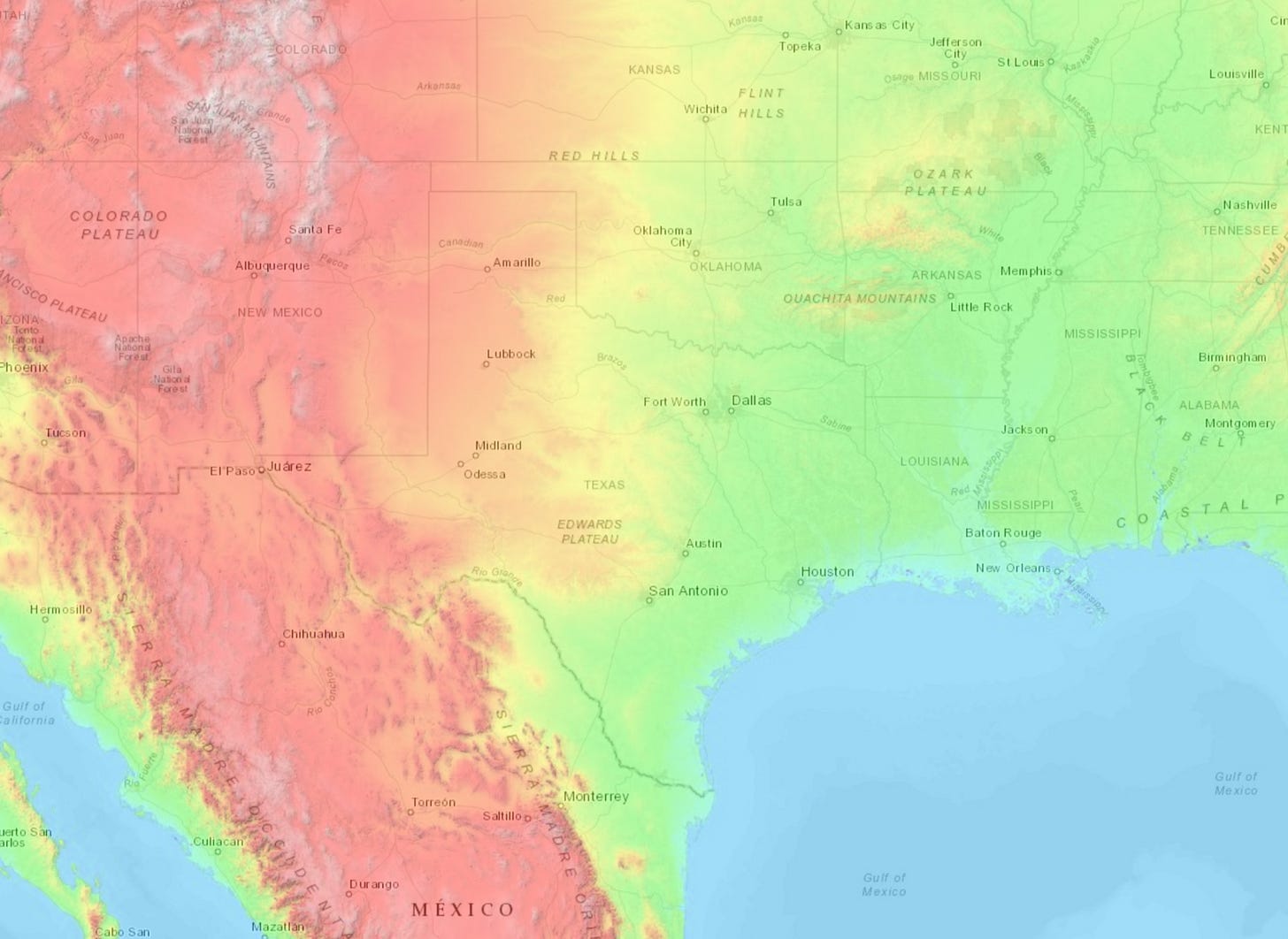

You can see the Texan Edwards Plateau in red to the west, converting into lower hills and plains to the east. Where are the cities placed?

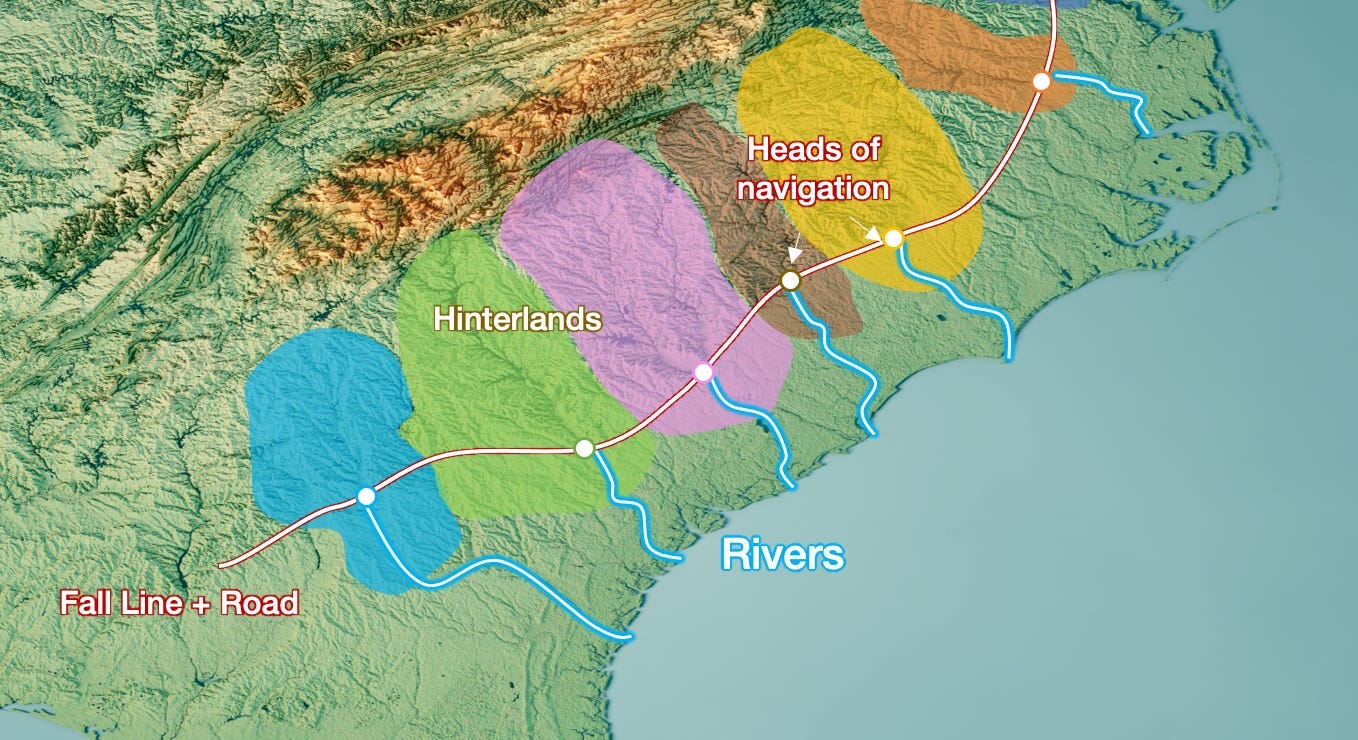

All these cities are at the foothills of the Edwards Plateau! It's like in the Appalachians, as we saw in Why Cities Thrive:

And of course, whenever there’s mountains, you should look at rainfall:

The result is that the part of Texas east of the Edwards Plateau (which includes the Texan Triangle) will have more rainfall than the west, making it more suitable for agriculture. When you look at a satellite map of Texas, you can see that translated into a gradient of green, from browner in the west to greener in the east. But because this is mostly a gentle slope beyond the fall line, there’s no dramatic rainfall and vegetation change.

So far, nearly everything is according to our principles. These cities were formed in the crossing of lines: between rivers and mountain fall lines, on the flatter side that receives more rainfall.

It still doesn’t fully explain why Dallas and Fort Worth are separate though.

Yes, the Trinity River does have confluences of its tributaries where Fort Worth and Dallas are, which is also on the Texan fall line. And yes, being on that fall line, it meant Fort Worth was on a cattle trail, which meant it became a center for cattle.

But is that enough? If it were true, they would have grown fast in the 19th century, but they didn’t. So something else happened.

Dallas and Railroads

You can only trade cattle if you’re connected to the world. If your rivers aren’t connected to the world, how can you trade that cattle? Through railroads.

The major north–south (Houston and Texas Central Railroad) and east–west (Texas and Pacific Railway) Texas railroad routes intersected in Dallas in 1873, thus ensuring its future as a commercial center.—Source.

But why did two railroads meet in Dallas to begin with? What was special about Dallas, besides being at the confluence of two barely navigable tributaries?

It’s on a ford of the Trinity River!

The city was founded by John Neely Bryan, who settled on the east bank of the Trinity near a natural ford in November 1841. Bryan had picked the best spot for a trading post to serve the population migrating into the region. The ford, at the intersection of two major Indian traces, provided the only good crossing point for miles. Two highways proposed by the Republic of Texas soon converged nearby.—Source.

You can see the ford today in the topography maps:

So Dallas was at the crossing between two rivers and two trails, which would soon become roads, which would then become railroads.

Meanwhile, Fort Worth was not too far away, but in practice was distant because the river was not navigable. And it was itself on another line, one for cattle. This cattle ensured that the railroads would reach it too, allowing it to also thrive independently from Dallas.

The railroads allowed these two cities to trade the production from their hinterlands to the rest of the world. Later on, oil was found around both Fort Worth and Dallas, further fuelling their growth, and justifying more infrastructure. The more infrastructure there was, the more the markets grew, the more the population grew, the more it specialized, the wealthier it became, the more it invested in infrastructure (like the Dallas–Fort Worth airport), the more it grew… Up till the moment they met.

I find this example interesting, because you can still see the impact of the lines in their growth, and how specificities of the land (here, the many lines despite no navigable rivers) create specific situations (here, two cities that grew close to each other).

San Antonio and Austin

It also explains the Texas Triangle. It’s not really a triangle: It’s a line between San Antonio and Dallas–Fort Worth, and then Houston.1

The cattle line followed the fall line, and so did the roads later on and the railroads after some time. Today, that’s where you can find the Interstate 35.

Each one of these had a natural stop at the crossing with each river, and a city appeared in each: Brazos for Waco, the Colorado for Austin, the San Antonio for San Antonio, and of course the Trinity and its affluents for Dallas and Fort Worth.

And then there’s Houston.

Houston

Usually, you don’t want many ports close to each other, because they would divide their goods, which defeats the purpose of a hub. So, many ports can emerge in a region, but they will follow a power law, with the biggest one being much bigger than any other.

If you look at the biggest US ports by tonnage, however, this is not what you see:

You have one port for the Mississippi (New Orleans), one for the West Coast (LA), one for the Atlantic / Great Lakes (New York), and around them no less than three Texan ports! Why?

Corpus Christi is mainly focused on oil and its derivatives.

Beaumont has a heavy military component.

If you take these unique conditions away, Houston is the one gigantic port in Texas.

Why did Houston win?

If Texas had had any long, navigable river, its head of navigation and its mouth would have become important cities. But it doesn’t have any, so any big coastal settlement with a good natural harbor could have become the main port of the region.

Originally, Galveston was the biggest port, but a hurricane destroyed it in 1900. The authorities learned a lesson that Europeans had learned over the centuries: Don’t build your cities straight on the coast.

The port activity moved upriver from Galveston. By that time, Houston was the head of navigation of the Buffalo Bayou, at its confluence with the White Oak Bayou, quickly making it one of the biggest ports. More importantly, its promoters had already built many railroads connecting it to other parts of the country, such as Galveston, New Orleans, San Antonio, or Dallas.

From what I can gather, it was this early advantage, combined with the move from Galveston, that put it ahead of the competition.

The Texan Triangle?

Why is there a Texan Triangle then?

Humid winds from the Atlantic rain over eastern Texas until they hit the Edwards Plateau: As air moves up, it cools and drops most of its remaining moisture, forming rivers that flow down from the plateau.

The Edwards Plateau falls into flatter terrain in a fall line. This fall line is perfect for a trail, and then a road: It’s as far west as it can be while remaining flat. The intersection of this fall line with the rivers creates ideal spots for cities to appear, including San Antonio, Dallas, Fort Worth, and the smaller Austin and Waco between them. Railroads strengthened their communication.

These cities needed a port to connect with the broader world. The best port would be one with a good natural port, as close to the inner cities as possible. It turns out that Houston is a good natural harbor, protected from the sea unlike Galveston, and it’s as close as you can get to the sea for cities like Dallas, Waco, or Austin, and just a bit farther for San Antonio. So Houston was a great spot for a port for these cities, which is why it quickly received railroads connecting it to the rest of Texas cities and to New Orleans. This put it ahead of the competition for biggest ports in Texas, and made it into one of the biggest in the world.

Next up: Atlanta!

A triangle is made of three edges, not one edge and one point.

![[Flag of Fort Worth, Texas] [Flag of Fort Worth, Texas]](https://substackcdn.com/image/fetch/$s_!Y2UM!,w_1456,c_limit,f_auto,q_auto:good,fl_progressive:steep/https%3A%2F%2Fsubstack-post-media.s3.amazonaws.com%2Fpublic%2Fimages%2Fc8e856a7-d557-438a-907d-a198ad8c1c3f_367x216.png)

I had always assumed - rightly or wrongly - that the abundance of natural freshwater springs along the fall line was one of the reasons the fall line was a good place to settle.

San Marcos, between San Antonio and Austin, is the oldest continuously inhabited area in North America because it's had nonstop freshwater springs for thousands of years.

IDK how big of an advantage this was once deep wells or plumbing to bring water from rivers or reservoirs became common, though.

Really interesting!

Weirdly enough, this is probably the first time that I pay attention to a topological map of Texas, and it explains a lot. Quite cool also all the history behind Dallas and Fort Worth, I didn' know that either.