Why Some Cities Thrive

Part 1 of How to Understand Cities

The Internet is changing cities under our feet—from London to Lima, Los Angeles to Lagos—and we don’t realize it. To understand what is happening to them and predict how they will change in the future, we need to understand first why cities are the way they are today. The more I dug into it, the more questions I had.

Why do empires rise and fall but cities remain for thousands of years?

Why do some cities grow and others remain tiny?

Are there rules that determine their distance to other cities? Their position? Their size? Their shape? Their density? Their infrastructure?

How does technology influence all of this?

Why do some cities thrive while others don’t?

I’ve been exploring this topic incessantly over the past few weeks and I’m writing a series on the topic. Today we have the first part: Why are cities where they are?

What I discovered is that the most successful cities are not where they are because of luck, and nothing any person could do would have a significant impact on whether a city is successful of not. Hidden forces determine the success of our cities. Here they are:

Eternal City Life

Even as empires rise and fall, their cities endure, continually inhabited for thousands of years across India, Pakistan, China, the Levant, Italy, Greece, Spain, the Balkans, and many others1. Why do cities live forever? To understand that, we must understand why cities exist in the first place.

Around 10,000 BC, the last ice age ended2, creating the conditions for agriculture to appear, which happened very soon after, independently in many different places. These spurts happened near rivers, because that land is the most fertile: They brought the water and their floods brought the fertile silts.

The increased land productivity meant more food.

More food meant more population.

The increase in food productivity also freed some people to specialize in other things.

Like wars. There were enough people to build armies and food to feed them.

Armies allowed them to enslave other cities’ populations, forcing the conquered to work on the invaders’ fields and make them richer.

Other types of specialization included industries like pottery, masonry, or blacksmithing.

And trade.

Rivers facilitated trade: In Roman times, it was at least five times cheaper to carry goods by river than by road3.

Trade brought wealth.

The river and its floods brought the need for infrastructure: irrigation and flood protections.

Which could be built thanks to the wealth and specialized skills.

The grains brought storable wealth.

The storable wealth, specialized industries, and trade attracted neighbors who wanted to take them over, and so they tended to invade each other.

This is why throughout history, agriculture consistently spawned civilizations on rivers, creating trade, armies, cities, and states.

This suggests the five reasons why cities initially emerge:

Administrative center for the state: Who is going to manage the infrastructure for the river? The people and taxes to build them? With limited communications technology, you want all the leadership in one place, close to the region it manages.

Military center for defenses and the army: Who is going to defend the administrative center? The region’s services, farmers, and their grain? Who will coordinate the armies? You need manned defensive walls, but they’re expensive, so you want them as small as possible, so you want to concentrate people in one well-defended place.

Market center for the trade of the countryside’s goods. And if you go to the market, you want everything in one place, so you can sell your goods and buy other people’s. The more buyers and sellers in one place, the better.

Specialized production center to serve the city’s rich and the countryside: blacksmiths, clothmakers, potters, innkeepers, coopers…

Infrastructure center. You want to concentrate your infrastructure where people live: ports, roads, paved streets, fortifications…

These reasons are crucial, because they define nearly everything about cities, to this day.

The Five Children of Agriculture

1. Administrative Centers

Cities were meant to manage the region around them, so they couldn’t be too close to each other. They needed a “catchment area” to manage. The more fertile and accessible the region, the bigger the centralized administration and its catchment area needed to be. This is one of the reasons why big cities from ancient civilizations were so spread apart.

But since the catchment area had to be fertile, and river banks were the most fertile, cities tended to be close to the river: More wealth to administer. But not quite on the river because of defenses.

2. Military Centers

If you want to defend your city, you better not put it in a defenseless position on the river. Ideally, you’re close to the river, but in a position that’s defensible.

That’s why Rome is on the Tiber river, but was originally built on the Palatine hill. It’s why many cities like Carcassonne or Salzburg were built on a river, but the fortified city lies on a nearby hill.

Why Athens was originally built on the Acropolis (“High City”) hill overseeing the nearby valley.

Why Paris was built on an island on the Seine.

OK so you want a big fertile area with water, along a river, and a defensible position. What else?

3. Market Center

Early on, cities also functioned as the primary market for the countryside. People could go there to trade local goods. But the cities that grew the most were the ones that could connect with other markets, attracting more goods, more trade, and more wealth. The best way to connect to other cities is to be at a crossroads, so you are accessible to as many other markets as possible.

Originally, roads were expensive. It took humans thousands of years to start paving streets, and the first true road was only built in around 400 BC4. So most trade was on rivers, meaning the more successful market cities were very close to rivers.

But the cities that grew the most were the ones at the confluence of rivers. This is striking in France, for example, where you can tell where rivers are located based on the population density: The population follows the river, with the biggest population centers at the confluence of rivers.

You can see these two requirements of military and trade strikingly met in Lugdunum—Lyon today—the capital of France in early Roman times. It was set at the confluence of the Rhône and Saône, and yet the main city was not on the confluence itself, but on the nearby hill for defense.

But cities didn’t only grow bigger at the confluence of rivers. Another ideal place to be was at the head of navigation.

Head of Navigation

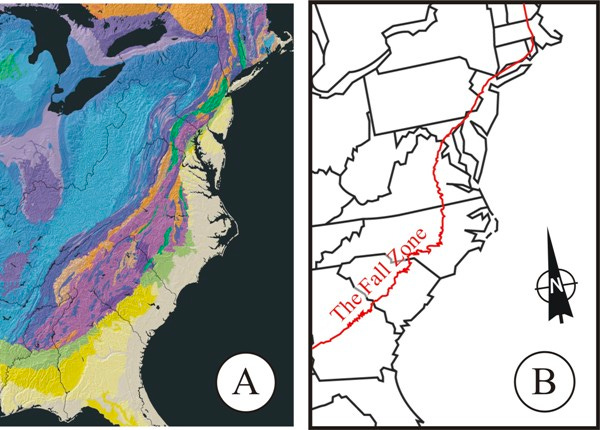

What do all of these cities have in common: New York, Philadelphia, Baltimore, Washington, Richmond, Raleigh, Tallassee, Tuscaloosa? They are eight of the over 30 cities on the Eastern Seaboard on its tectonic line.

This red line is the Atlantic Seaboard Fall Line.

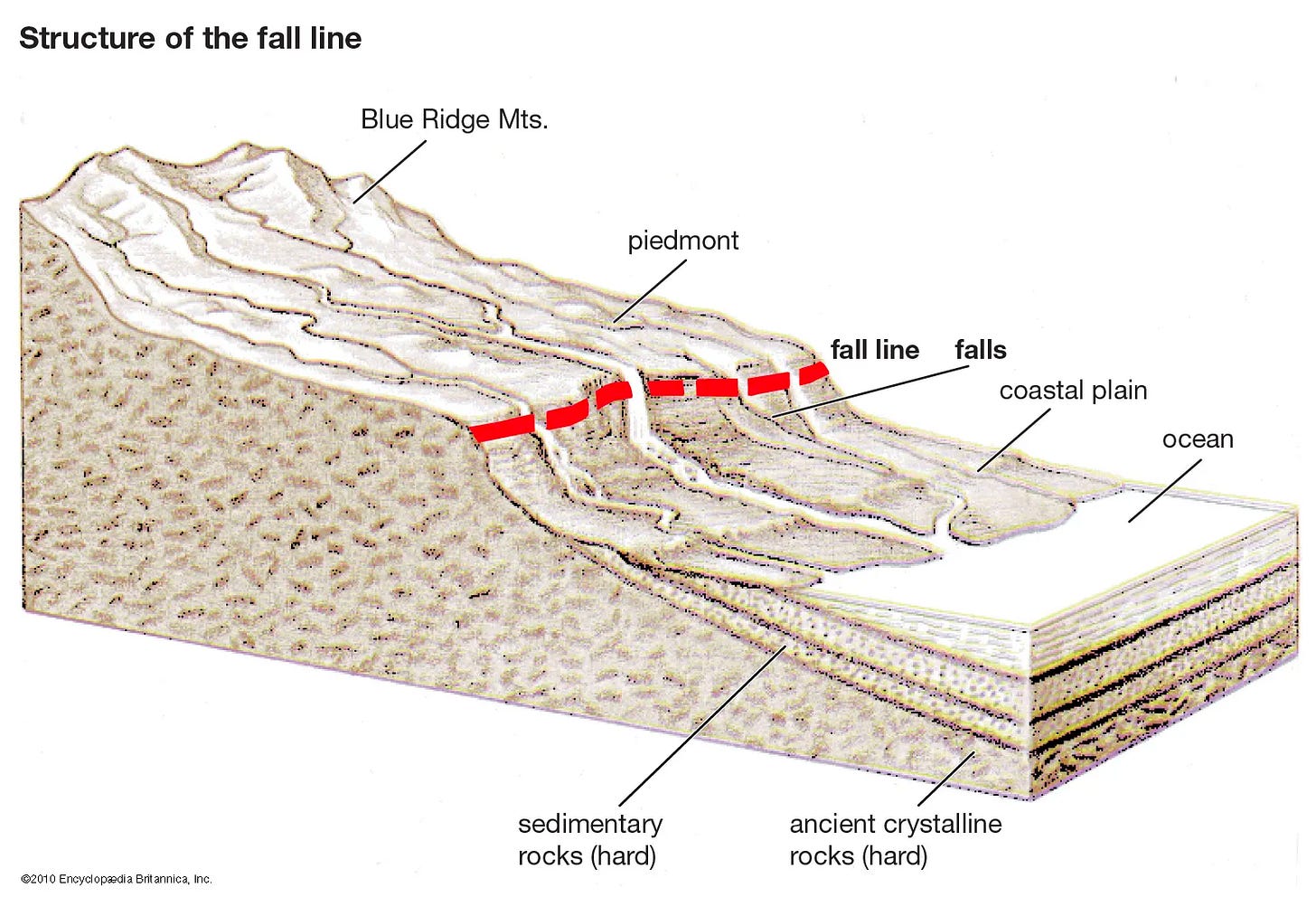

The Fall Line marks the division between the end of the Appalachian mountains and the beginning of the Atlantic Coastal Plain.

The I-95 interstate was built on top of it, to connect many of the most important cities of the US East Coast. But why are so many cities on that fall line to begin with?

On the Atlantic side of that fall line, everything is very flat. West of the fall line, hills appear.

Rivers are not navigable when they go through hills. Water is too fast, it crosses too many rocks or waterfalls. But on the plain, waters are calm and navigable. The head of navigation of a river is the farthest you can go upriver on a boat. So the heads of navigation of rivers frequently follow a fall line.

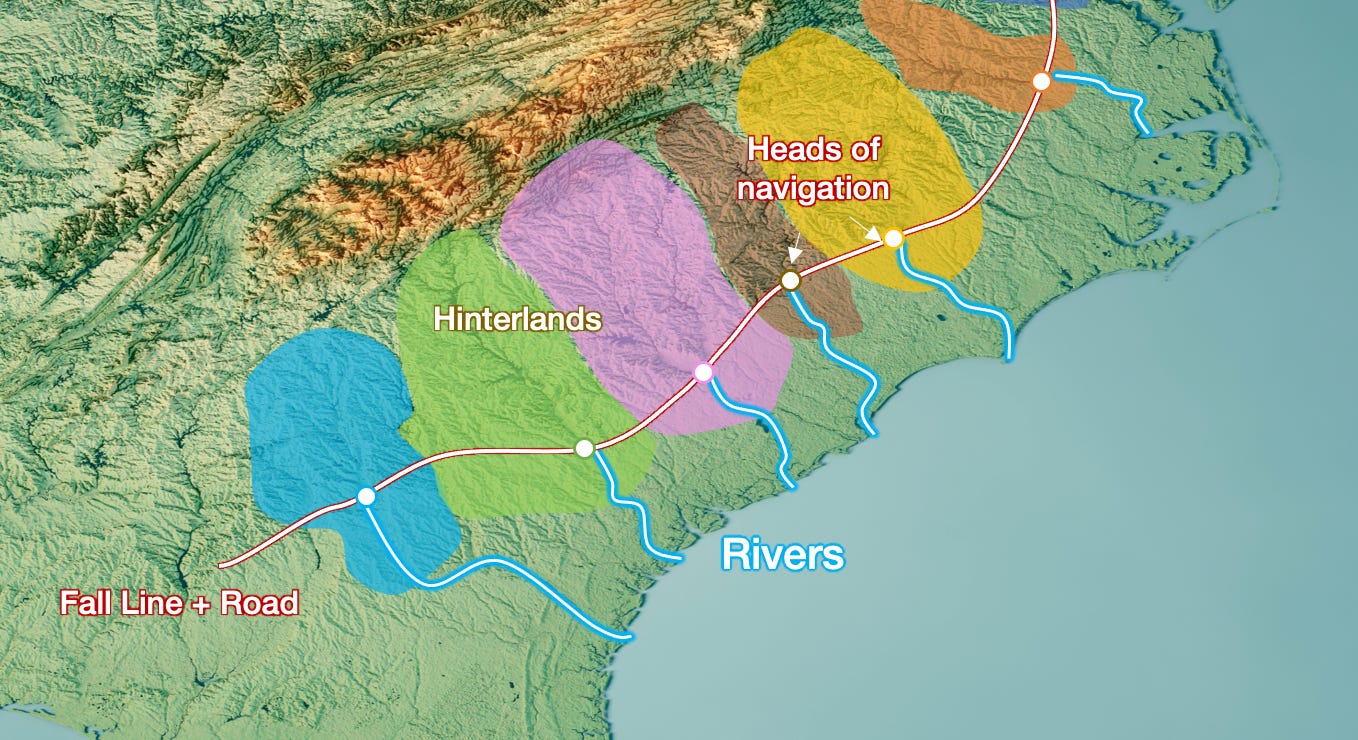

Cities founded on heads of navigation will tend to grow richer, because they can trade everything coming from the hills with the rest of the world. In the US East Coast, the heads of navigation are the trading capitals of their Appalachian region5.

The exact same thing happened about 2,000 years ago in Italy. When Romans conquered the Po Valley, they could have built a road anywhere they wanted. It’s quite flat.

But they decided to build their Via Aemilia along the fall line of the Apennine Mountains. They then created colonies along that road, usually where there was a river.

This is why today Italy’s biggest cities in the southern Po Valley are all in a straight line.

Roads like the I-95 Interstate in the US and the Via Aemilia in Italy have another crucial function: crossroads. By connecting all the heads of navigation between them, the hinterlands are connected not just to the world through the river, but to neighboring mountainous regions too.

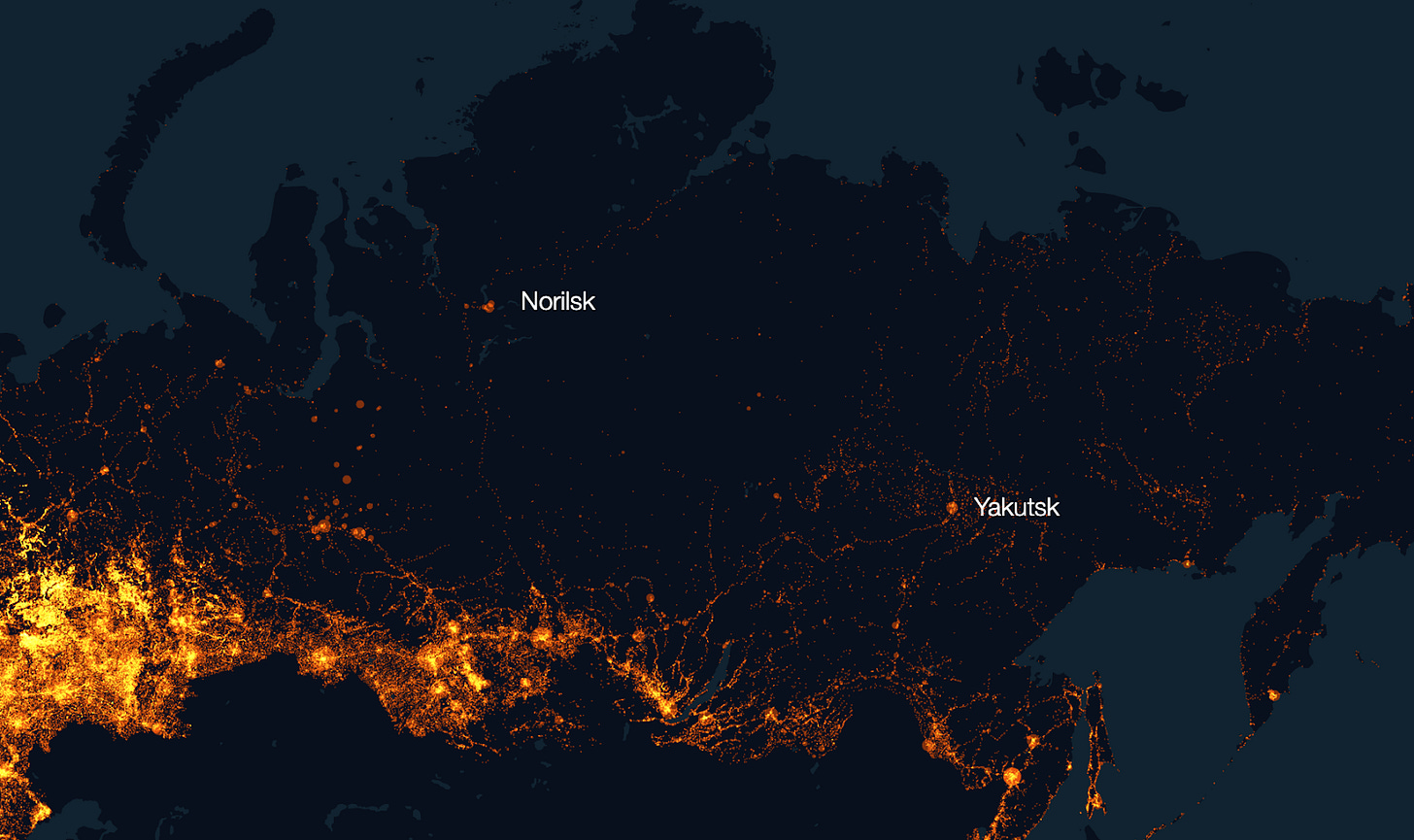

This is true for every communication way: rivers, roads, railroads… For example, we can see this in Siberia: All the main cities are on the Trans-Siberian Railroad, and the biggest ones also cross big rivers, like Omsk (Irtysh river), Tomsk (Ob), Krasnoyarsk (Yenisey), Irkutsk (Angara), etc.

Even in the most remote areas of the world like Siberia, most of the cities are either on a railroad, a road, or a river, and the biggest ones are on their crossings. We can see their lights follow the lines.

Rivers, roads, railways, fall lines… The bigger they are, the bigger the cities at their crossings.

There is another type of line that’s even more special: coasts.

Before humans developed sailing technology, it made little sense to settle on the coast: There was not much benefit compared to a river:

Less trade, as nobody knew how to sail the seas reliably.

Less fertility due to salinity.

Swamps, and the corresponding difficulty with agriculture, floods, and diseases like malaria.

Storms.

But once sailing technologies developed, the sea had something special that none of the other lines had: It allowed to easily trade not just with cities connected to your roads or rivers, but with any city on the sea.

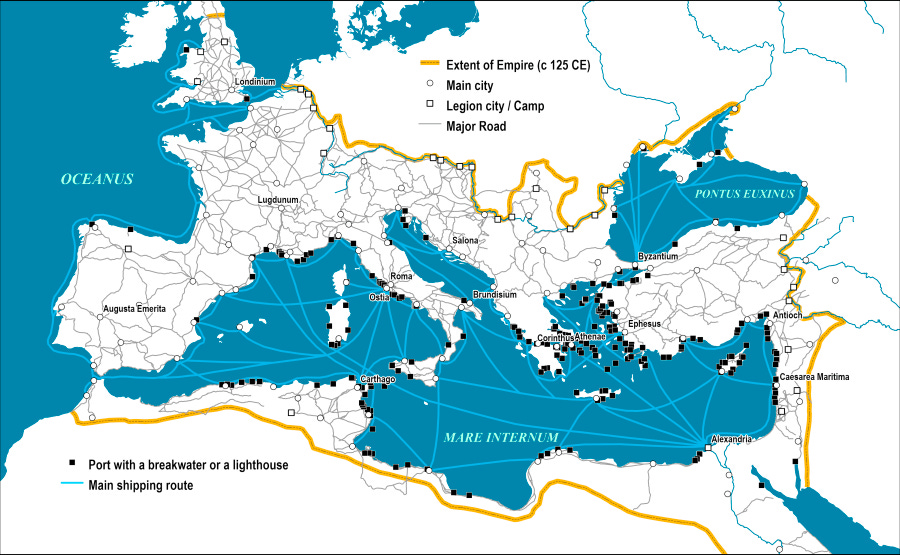

This is why the civilizations that mastered Mediterranean navigation thrived.

But the biggest cities are seldom on the coast itself, but rather somewhat inland of major navigable rivers: London (Thames), Rome (Tiber), Paris (Seine), Seville (Guadalquivir), Valencia (Turia)... We see the same thing in the biggest ports in northern Europe: Antwerp, Rotterdam, Amsterdam, Bremen, Hamburg, Lübeck… All are close to the sea but up a river.

The same is true of many cities around the world. For example, in the US: New Orleans, New York, Houston (in the Galveston Bay), Mobile AL, Hampton Roads, VA, Baltimore, Pittsburgh, Savannah… All are seaports on rivers or protected bays. Why?

There are several advantages:

Military: Defend more easily against seaborn invaders.

Commercial: Easily trade with both river and coastal cities, and cover more of the hinterland.

Safety: Storm protection.

Infrastructure: Rivers have land on both sides, which doubles the interface between water and land, and allows for more docking space.

This last point can be seen in Rotterdam, the biggest port in Europe.

When cities were on the sea itself, there was usually a good reason: They had access to a nearby river (eg, Marseille and the Rhône), they had a strategic position (eg, Byzantium, modern-day Istanbul), there was simply no big navigable river around (eg, most seaport cities in Greece).

In fact, it’s not a coincidence that two of the richest regions in the world are Northern Europe and the US East Coast: Both have big flat plains for agriculture, downstream of a range of mountains that produces a high density of long navigable rivers to bring their production to the world.

OK, so we’ve established that the cities that will grow the most are optimized for trade. They are defensible, have connections to a productive hinterland, and are at the crossroads of key lines: rivers, roads, railways, fall lines, and coastlines.

But their production didn’t always need to be agricultural.

4. Specialized Industries

As I explain in A Brief History of the UK:

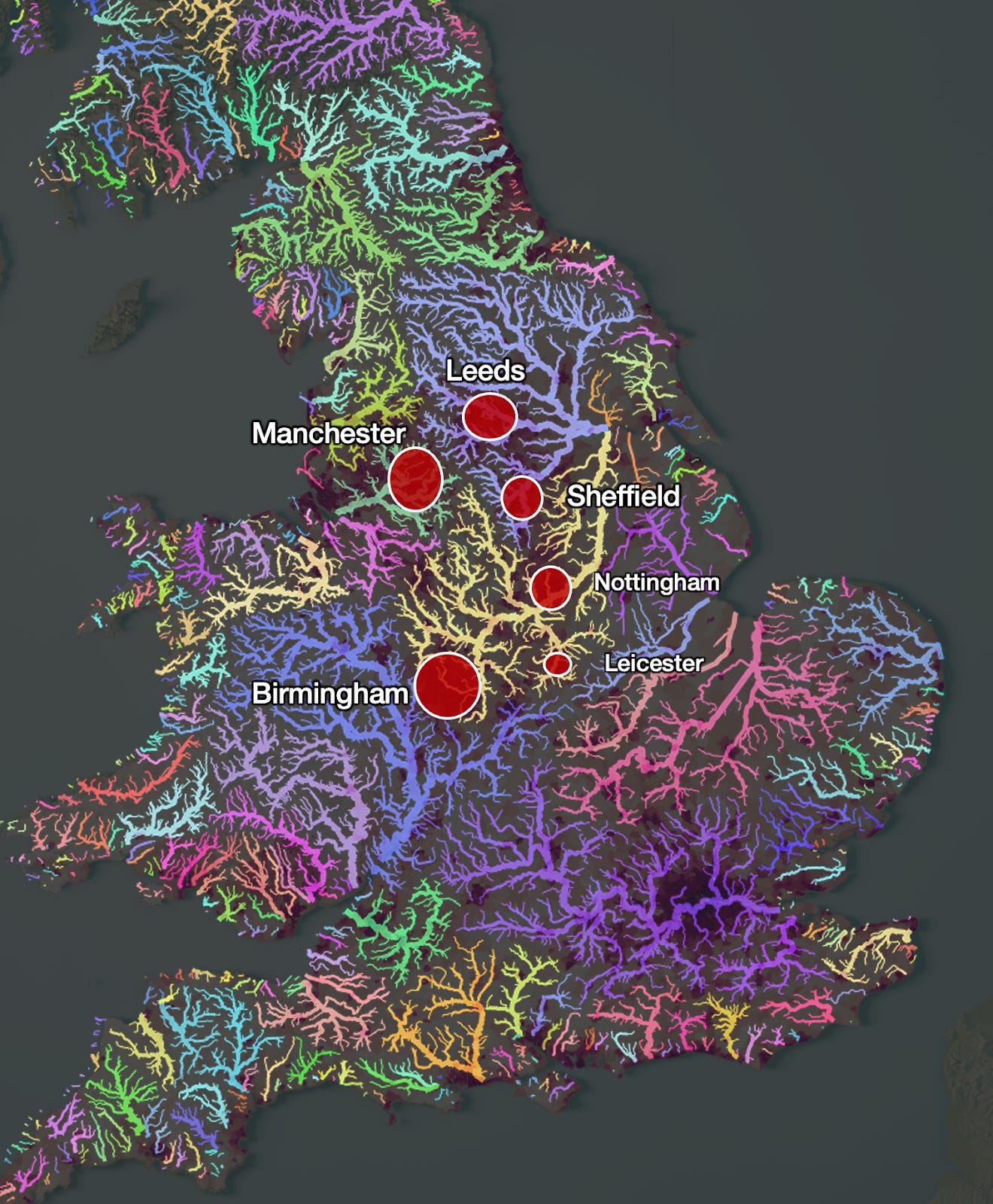

Three of the top four cities in the UK are not on the coast or on big rivers: Manchester, Birmingham, and Leeds.

Newcastle, Liverpool, Cardiff, and Bristol are all on the coast and most are close to navigable rivers. This is not true of the circled cities with their names in red. The river Aire and Irwell that go through Leeds and Manchester respectively were not navigable until 300 years ago.

To give you a sense of the size of their rivers, this is Birmingham’s Rea River:

And this is not due to canals taking the water from rivers away. Outside of Liverpool, not a single big Northern England city is downstream of a big river.

None of these cities was on a river, coast, head of navigation… So how did all these cities become so big?

They were all backwaters until the Industrial Revolution.

Leading up to then, Manchester specialized in cotton, Leeds in wool, and Birmingham in ironworks. This region started building canals in the 1700s, which started accelerating the growth of these cities.

They were lucky to also have lots of coal around, and a political system open to innovation. When England ran out of wood to burn, coal mining became much more important. But coal mines frequently filled with water, which needed to be pumped out. As coal became more valuable, there was demand to automate the extraction of water to increase the mining productivity. This is what spurred the practical adaptation of the steam engine. Specialized industries in the Midlands saw the potential of the new technology. Suddenly they were producing textiles more cheaply and reliably than anywhere else in the world. The canals allowed them to be traded with the world too. And this is how the Industrial Revolution emerged in that area6.

So a geographical combination of coal, local specialized industries, and a favorable political system allowed some regions that didn’t have great natural reasons to grow to become world-class cities.

Mining has historically been one reason why cities emerged. The two biggest cities in permafrost regions, inside the Arctic Circle, are Yakutsk and Norilsk, with over 200,000 citizens each.

Both are mining centers: Norilsk has the biggest reserves of nickel in the world, Yakutsk has gold, diamonds, and tin. You can see the cities at night, but also all the lights of the small settlements in the hinterland around Yakutsk—probably mining?—and along the transport systems that connect them to the rest of Russia.

You can see something similar in Mexico, where the Spaniards built cities along the Camino Real to the silver mines of Zacatecas.

Another type of island cities are the weird administrative centers built in the middle of the regions they’re meant to rule, but without any consideration for the actual geography they settle. Two examples that spring to mind are Burma’s Naypyidaw and Brazil’s Brazilia.

What you do get more commonly are cities that first form at the intersection of various trade routes—rivers, railroads, highways—that then begin to specialize. The US is the best example of this phenomenon, with Internet tech in San Francisco, media in LA, oil and gas in Houston, automobiles in Detroit, academics and healthcare in Boston, and government in Washington. Every single one of these cities has good navigable waterways that connect to the sea, except for LA7, which only has the sea.

All of this leads us to the final point.

5. Infrastructure Centers

Cities on rivers need embankments, dams, irrigation systems, bridges. Cities on the coast need ports and safe harbors. They all need paved streets and roads to connect them to other cities. Or railroads. Or highways. Or all of them. These investments cannot be repeated everywhere, so the bigger cities get them first, which makes them even bigger.

Take London. It’s located at the point where the river Thames meets its estuary. In ancient times, it was a natural border between tribes and chiefdoms. But once the London Bridge was built, it became a key passage across both sides. That made it a natural trading hub, but also a strategic point to be defended. So the infrastructure, military, and trade came together.

Given its strategic importance and growth, it made sense to build roads that connected it to the rest of the country. This is what Romans did. And for every road they built, a new line intersected London, and its advantage grew, starting 2,000 years ago with the Romans.

But the Thames was wide and marshy. It needed infrastructure investment to gain space on the river, which made the river narrower and more navigable. But this investment would have never come in the first place if London hadn’t been important, owing to its prime position, its bridge, and its roads.

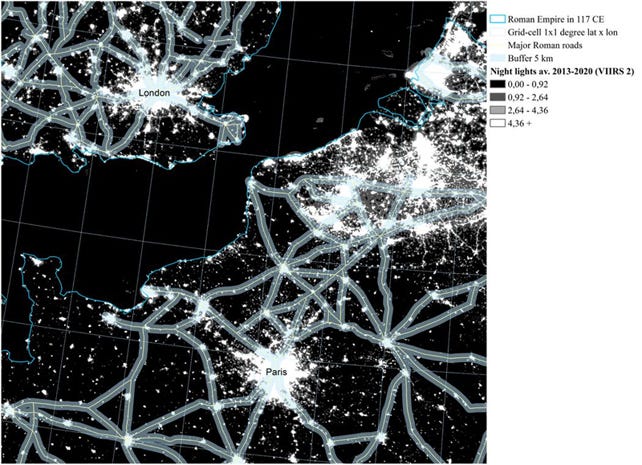

A paper recently illustrated the lasting power of infrastructure: Regions near Roman roads, built 2,000 years ago, are wealthier today than other regions.

Although this is a correlation—are these regions wealthier today thanks to the roads, or were roads built in great places that would have been wealthier anyways?—it looks like it might be a causation, because in North Africa and the Middle East, where trade was taken over by camel caravans that didn’t use Roman roads (which fell in disrepair), and so they weren’t forced to keep using the same market cities, which suffered as a result. Infrastructure does cement the power of cities.

Nowadays, the infrastructure of choice is the airport, which is expensive to build and maintain, so only big cities can afford them—which makes them bigger still.

But airports don’t behave like any communication line we’ve discussed. Instead, a city with an airport can be connected to any other city in the world. How should we interpret that?

Hub-and-Spokes

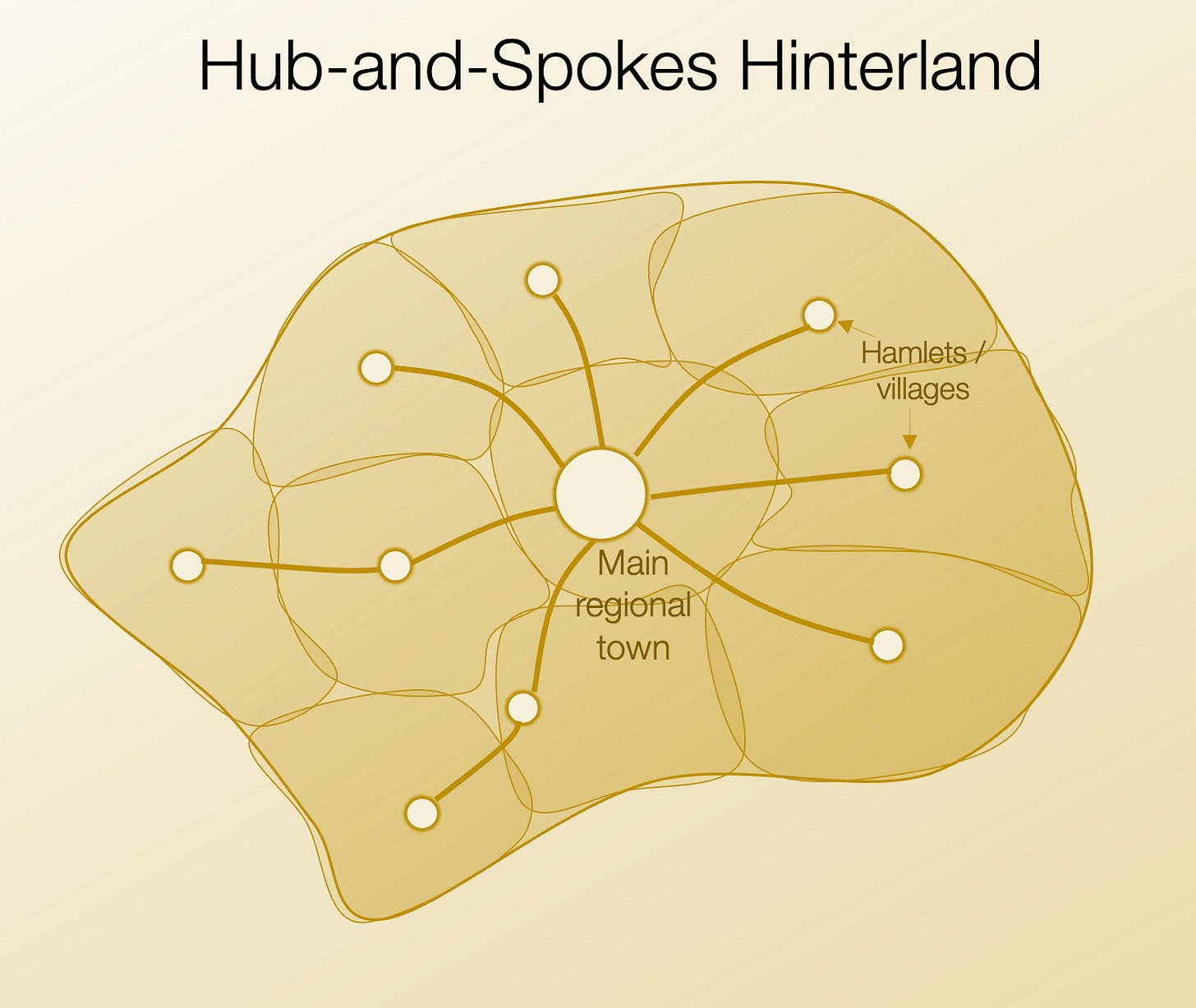

Earlier in the article, we explained how the primary market role of cities was to be the trade hub of their hinterland.

The main town was the hub, with spokes going to the smaller villages or hamlets in the region.

The same concept is true for cities at the mouth of a river: They act as a hub for the entire river basin, connecting it to the ports on the sea. They serve the spokes on both sides: rivers and sea.

Some cities could go further and emerge as hubs between different influence regions:

Rome started as the main hub between the Italian Peninsula and the western Mediterranean, and eventually became the hub between all Mediterranean cities and inland Europe.

Constantinople became the hub between the Mediterranean and Black Sea, Asia Minor and Europe.

London was a hub between England and Northern Europe, and eventually became the hub between the UK and its colonies.

Rotterdam was originally the main hub between the Rhine river and the North Sea, and eventually grew into the main sea transport hub between the Atlantic and Europe.

In every case, a big original hinterland was used as a springboard to become a regional hub, which in turn gave the city an outsized importance.

Airports have done the same thing: Cities well positioned between different regions could emerge as air transit hubs, which would attract infrastructure investment, and a further cementing of their lead.

The four airports with the most passengers in the world are all in the central US (Atlanta, Dallas, Denver, Chicago). All can serve the entire US with short trips, so are well positioned as US hubs (which they are for Delta, American, and United for the last two). Notice the contrast with the biggest US cities. You don’t see the bigger coastal cities of New York and Los Angeles, for example.

Similarly for international travel and trade, Dubai and Istanbul are the two main airports, as they function as hubs for Europe, Asia, and Africa. Hong Kong is the main airport for cargo, as the hub for China with the world. Madrid is the main hub between Latin America and Europe.

Notice that in some of these cases, these cities were not blessed with amazing access to sea or rivers. But airports gave them access to regions that they could exploit.

The same story every time: The best local hubs could become regional hubs, and the best regional ones became national, and then international.

Takeaways

Humans settled any place where they could extract wealth from the land—whether by growing food or mining. But out of the millions of such places, only a few grew consistently over the centuries:

The ones that were surrounded by the most productive areas.

Within those areas, the places that could be well defended.

Out of those, the ones with the best lines: navigable rivers and coasts.

Out of those, the ones with the most intersections: fall lines, river confluences, river mouths on the coast…

These cities received the best infrastructure: roads, canals, railways…

Which further increased their line intersections.

All these intersections increased wealth through trade, which further attracted investment in infrastructure, which further cemented their lead.

The ones close to the sea could become sea hubs, furthering their lead. Airports then generalized these advantages to well-positioned regional hubs, even those without huge access to rivers or seas.

And this is why cities last forever: They are on the best land, and the best land doesn’t change. They attract the most infrastructure investment, which lasts a long time and creates network effects.

This has many consequences for the future. For example, have you heard about this trend about special economic zones in weird places? They are unlikely to succeed unless somehow they get access to some prized land that wasn’t developed, or technological progress eliminates some of these geographic advantages.

But there is still some underdeveloped land, and there are new technologies that are changing these geographic advantages. Where could new cities be born?

We will also answer other questions: Why are cities fractal? How do network effects affect cities? What determines the shape of cities? What is the role of technology in all of this? I’ll be writing about these topics in the upcoming articles. Some of them will be free, some will be premium. Subscribe to read them all!

Some ancient cities were abandoned, such as Pasargadae in Iran, Ur in Mesopotamia, the Greek Sparta, Troy, or Ephesus, the Roman Leptis Magna, the Mayan cities, and the Khmer Angkor. But most of these cities went through some sort of unique catastrophe, and for every one of these lost cities, dozens remain.

Unclear why. The fluctuations between ice ages and interglacial ages might be because of the Earth’s orbit, solar activity, volcanism…

This gap between costs of river and road transport was higher elsewhere. Other empires didn’t have the same quality roads, which means their overland transportation costs were higher than Rome’s. Their river costs would not be much higher comparatively, so outside of Rome (and maybe part of the Achaemenid Empire that did have roads), the gap between river and road transportation costs was higher, meaning the premium of living on rivers was even higher.

You guessed it, in Mesopotamia, “in between rivers”. The Royal Road.

Heads of navigation don’t only become major cities on fall lines. For example, Minneapolis is the head of navigation of the Mississippi and Pittsburgh for the Ohio river.

Massive oversimplification, but the point of this article is not to explain the industrial revolution, it’s to explain the specialization process of cities.

Its river was not navigable, as it dried out during the summer and flooded with the snow melts in the Spring.

Great article! Very educative! Thanks! That's what explains the importance of Ljubljana, the capital city of Slovenia. It is the biggest city in the region and as it happened, this region is stretching as far as the borders of the country. Ljubljana is located on a plain close to the river. Surprisingly or not, in the very heart of the city, one can even find a little hill with a castle positioned on the top. However, due to its closeness with Zagreb, the capital of Croatia, it has not a potential to become the administrative centre of Northern Balkans (Zagreb also has bigger and more important airport with worldwide connections).

P.S. This perfectly explains the rise and fall of Yugoslavia as well as its consequences.

Some observations. New York has so much traffic it needs three major airports plus three smaller. Washington area has three.

Heads of water can move due to technology and politics.

Québec City was a major port in the XIXth century but it was a french speaking city. The canadian government dredged the St-Lawrence river to Montréal. Still too french. So the St-Lawrence Seaway was built to bypass Montréal. But Malcolm McLean invented the container ship, removing the size constraint from cargo ships. Good luck blasting hundreds of kms of granite to let the new humongous ships pass, so Montréal instead of being replaced by Toronto, became the container port for the Great Lakes area.

But the Cdn government succeeded in demoting YUL in favor of YYZ as Canada's primary airport.