The Birth of German(y)

Goods, Gods, and Guns

This week is Germany’s elections, so it’s a good time to understand the country better.

You can’t undertand the country until you understand the unique way in which is was created. What is that?

Why is the country so rich and powerful?

Why so federal?

Why is Berlin the capital?

What lies in Germany’s future?

Why can we still see the old East/West partition on random maps of today?

Today, we’re going to start with the most important one: What is the weird way in which Germany was formed, and why does it define it to this day?

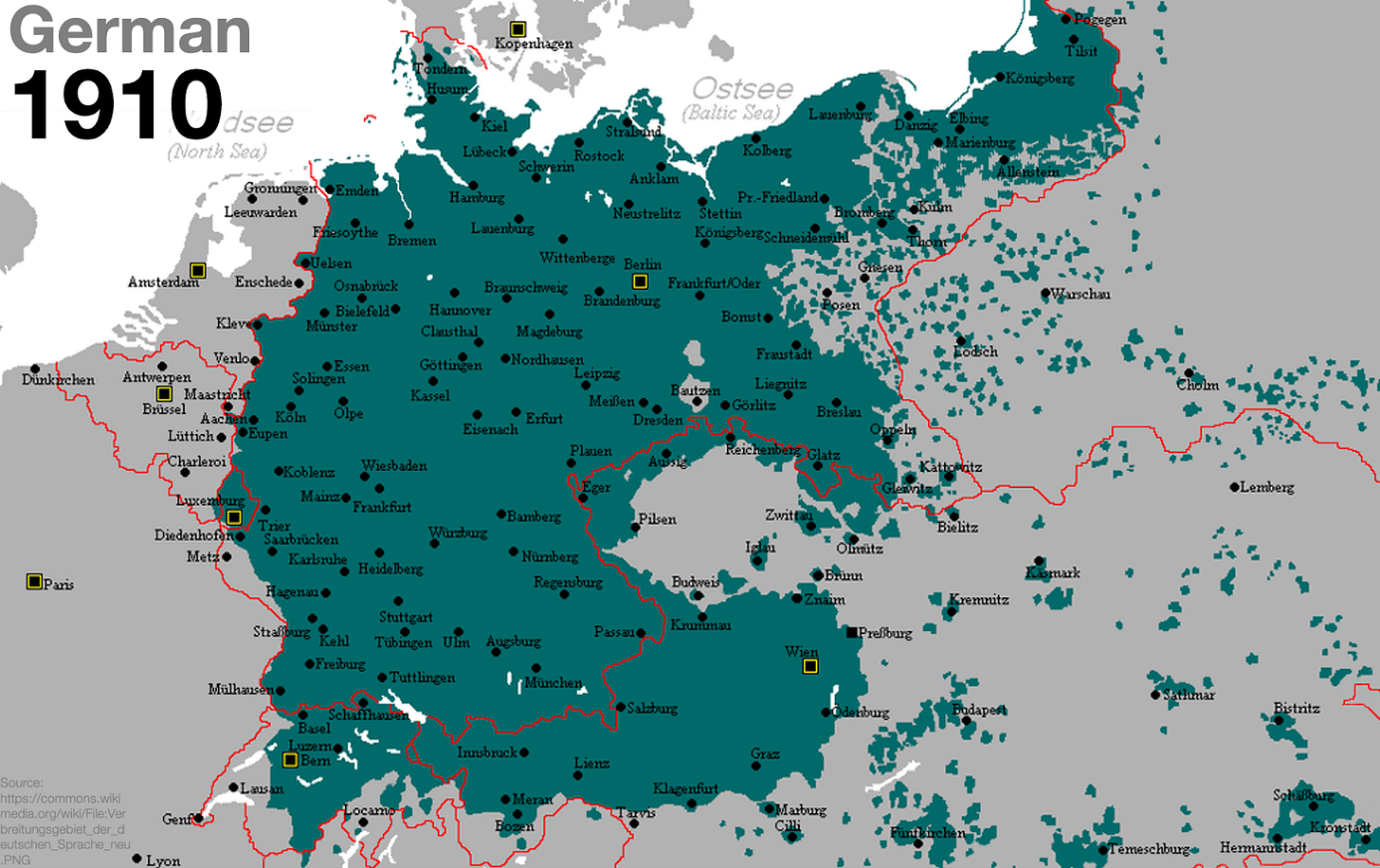

Germany’s birth has something unique. This map gives us a hint of that: German used to be spoken very widely across Europe, but within years of WWII, it collapsed.

You probably guessed this is due to WWII, but what exactly happened to the people who spoke German? How did German become so widely spoken to begin with—way beyond the borders of what is Germany today? How does this help us understand Germany, WWII, and even the attack of Russia on Ukraine today? Why were there so many pockets of Germans everywhere?1

How Did German Expand So Much?

For most languages, conquerors impose their language on the conquered people, who adopt it little by little. This is what happened with the Romans, for example: It took centuries for Latin to become the language spoken by the common people, mixing with local languages. Arabic came from the Arabian Peninsula, but is now spoken from Morocco to Iraq, albeit with different accents and dialects. Spanish spread through the Spanish Empire as a vehicular language and took centuries to become fully established, but the more remote areas kept some of their local languages, such as Quechua and Guaraní. English spread with the British Empire. Mandarin is wiping out about 300 languages right now…

This is not what happened with German. The language predates Germany! Why?

In fact, the very concept of “German” is misleading. There wasn’t a German language until very recently. What we now call “German” comes from the Indo-European family of languages:

As people from present-day Turkey developed agriculture, their superior ability to extract calories from land meant they could reproduce faster than their neighbors, and they expanded from there.

As they spread, they brought their language with them—Indo-European.

And the languages diverged.

This spread was anything but pacific. An early wave of farmers wiped out the existing population within a few generations. Then another wave of semi-nomads from the Russian steppe wiped these farmers out, again within a generation, around 2800 BC.

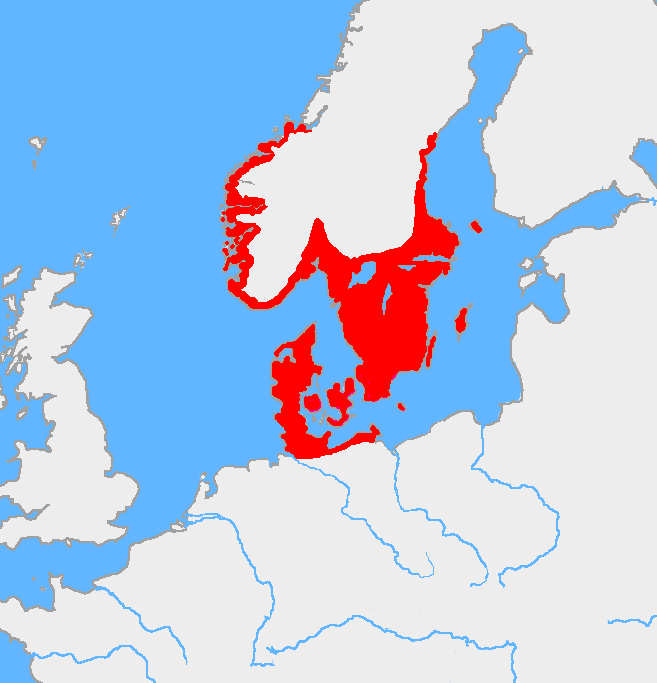

By the first millennium BC, the Proto-Germanic language had evolved in what is today Denmark and southern Sweden.

These people started expanding southwards, just as the Romans began expanding around the Mediterranean:

To this day, the areas that speak Germanic languages are all clustered around Denmark, northern Germany, and southern Sweden:

Why did the peoples from Denmark and Sweden start expanding south, and not, say, the other way around? I couldn’t find satisfying explanations. My hypothesis is that this area is very special:

The continental part of Denmark, the Jutland Peninsula, only has a thin connection to the continent of about 68 km (~40 miles). Hard to find, easy to defend because your enemies can only come from one direction.

It’s harder to go towards colder areas than warmer ones here.

The area is full of islands, hard to navigate for continental peoples, but easy for maritime ones.

In other words, the sea and the cold were barriers that were probably hard to pass for land-based people from the south.

And what did these northerners find as they went south?

The result was this:

So for centuries, Germanic tribes2 were in contact with Romans, learned their ways and their technology, and even formed part of the empire, more or less loosely. This made them stronger and more apt to fighting and replacing the Roman Empire, which is exactly what happened.

So what was happening was that peoples, originally from around Denmark, southern Sweden, and northern Germany,3 expanded south until they clashed with another people—the Romans. They learned from each other and when the Romans fell,4 the Germanic tribes expanded.

The pressure didn’t just come from the north. It also came from the west, most notably from the Huns and Magyars. They displaced local peoples—most notably the Goths and their variants, Ostrogoths and Visigoths—who then pushed into the Roman Empire.

Germanic in the Middle Ages

A few centuries later, around 800, it would be a Germanic king—the Frankish Charlemagne—who would unite France, Germany, and Northern Italy. This territory was so huge that he was considered the heir of the Roman Empire. Centuries after its fall, a new empire was formed: The Holy Roman Empire. The Pope crowned Charlemagne emperor.5

But Charlemagne divided his empire to share it with his three sons. The eastern part loosely resembles present-day Germany.

Since France had been occupied by the Romans for centuries, it was latinized enough that the Franks eventually adopted the local language.

Meanwhile, the Roman occupation of Germania had been mostly west of the Rhine, so east of it the influence had not been strong. The locals kept their language there. For the first time in history, there was a political union that spoke Old High German dialects.

It didn’t speak only that, because the Holy Roman Empire was huge:

But belonging to an empire doesn’t mean all subjects speak the same language. Especially in the Holy Roman Empire, where the elites might use Latin as a vehicular language. So how do we go from some tribes in Germany speaking Germanic languages to the spread of German across central Europe?

Trade

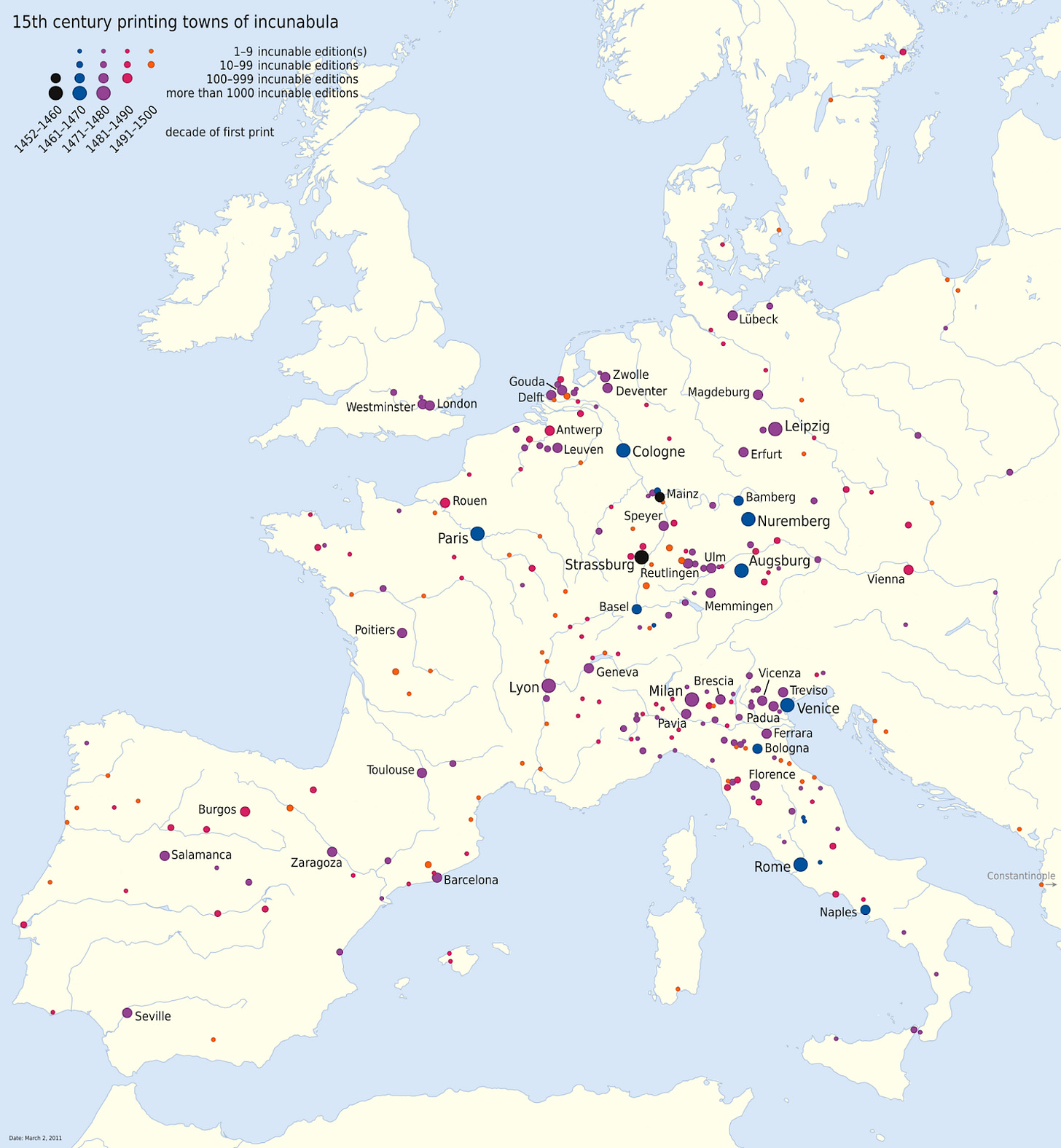

Look at this map:

You can see that in Roman times, variants of German followed river transportation: Dialects espoused rivers, and the farther you went from a river, the more differentiated the dialect was.6 This changed over time:

This map shows the difference in German dialects. As you can see, there are horizontal bands that correspond to…

The terrain.

The closer to the sea, the flatter the terrain. The farther south we go, the more hills and then mountains. Dialects follow this terrain. Why is this terrain like that?

The northern part of Germany is flat, criss-crossed with rivers, and has access to both the North and Baltic Seas. This is perfect for trade. Which is what happened.

As the Age of Vikings was drawing to a close, it was replaced by a boom in trade. In this area of the world, this meant the appearance of the Hanseatic League, a group of cities around the North and Baltic seas that united for trade.7 This union allowed them to fight piracy and help each other deal with continental lords who might have wanted to take over their riches.

Notice a few things. First, the heartland was in Germany. The cities of Lübeck, Bremen, and Hamburg were among the earliest and most powerful members of the Hanseatic League.

Many cities appeared across the Baltic, like Danzig (present-day Gdańsk in Poland), Königsberg (present-day Kaliningrad), Riga, Novgorod… Many of these cities were great natural ports and grew thanks to trade with the Hanseatic League. Some of them had been founded or settled by German traders.

What did they trade? Notice that many of these cities are not on the sea itself but on rivers.

Every city is at the intersection of rivers and the sea. Why? As we know, this is ideal for trade:

Being close to the sea allows for trade with all other sea ports.

Being away from the direct coast protects from attacks and weather.

Access to a navigable river means the goods from that river and its hinterland could be traded with other ports on the sea.

In other words:

Unsurprisingly, this region developed a similar type of German—Low German, as in “from areas low in altitude”. If you zoom in, you can see further dialectic variance.

Where transportation was easy, German trade went, and German culture went. It followed the rivers and seas of northern Europe.

But the Cross could also travel.

Religion

German-speaking people migrated towards what are today Poland, Czechia, Slovakia, Austria, Hungary, Serbia, Bulgaria, Romania, Russia… forming pockets of Germans: Traders, engineers, and Christian proselytizers either traveled to these lands by their own initiative or were invited by local kings. Sometimes, though, they were not invited.

While the more famous crusades involved taking field trips to the Middle East, the Northern Crusades against Slavic, Finnish, and Baltic people successfully expanded Christendom northeastwards. Between 1100 and 1250, there were nearly a dozen such crusades.

The Teutonic Order was a military society that christianized the Baltic and… decided to stay.

This evolved over time into Prussia, which was the biggest component of what would later become Germany.

You can see the pattern here, where transportation speed means more trade—and more cultural exchange—but also eases religious and military penetration, in a way that all reinforce each other. The easier the transportation, the more united the region. The harder it is to go somewhere, the more distant it becomes physically, culturally, religiously, and politically.

This concept can be seen in German dialects. As you travel south, dialects gradually turn into Upper German.

The farther south, the more distinct the language. The more mountains, the more intense the linguistic change, so much so that all the southern mountain ranges mark a radical transition between Germanic languages and others.

What facilitated German expansion was sea and rivers, and what boxed it in were mountains and mighty foreign powers.

This whole process took centuries, but a new invention would accelerate it dramatically.

The Printing Press

You saw it coming.

I’ve talked about this in the past so I won’t expand on it too much. Very quickly: The printing press appears in the mid 1400s and suddenly allows the production of orders of magnitude more books. The printing press spread quickly, especially within the Holy Roman Empire (HRE).

The spread was helped by the fact that the HRE was so decentralized, which we’ll explore in a future premium article.

One of the first wide applications of the printing press was during the Reformation: Martin Luther printed his German vernacular bible, which allowed the language to reach far and wide.

He was very careful to use the most generic German he could, and added glossaries to translate the most regional words into other dialects, so that as many Germanic people could read the Bible as possible.8

And one of the core tenets of Protestantism was that you didn’t need the Church to access God. You should read the Bible and interpret it yourself. This led to a dramatic increase in literacy rate in Germany.

As a rule of thumb, the more protestant, the more people read books.

You can see this starkly here:

The more people read, the more they spoke the same language. The more they spoke the same language, the more books were profitable, so more books were published. More people learned to read them. And supply and demand fed each other until a majority of citizens of the Holy Roman Empire eventually learned to read a similar German.

A New World Order

Books carried Protestantism, and Protestantism carried books, in a virtuous cycle. Of course, Catholics did not appreciate that, so the epicenter of printing (Germany) also became the epicenter of religious strife. So much so, that just a century after Martin Luther published his 95 theses started the Thirty Years’ War: Protestants and Catholics went at it, and all the neighboring countries decided to chime in, using Germany as their battleground, and killing between 30-50% of the German population.

The most important outcome of this war was the Peace of Westphalia, which ended the old order of religion above all, and was replaced by one of nation-states above all. States agreed that each one could decide the religion they wanted to follow, and neighbors wouldn’t meddle.

Following this, the big nation states in Europe tended to opt for a single religion. Meanwhile, the spread of books meant that a single language (usually the one of the capital) was used as the vehicular language of the country, and spread throughout the kingdom. The combination of single religion and language reinforced each nation state—except for the HRE, which was made up of hundreds of political units ruled by kings, princes, dukes, counts, bishops, abbots… Each one with its own religion.

In the early 1800s, the HRE learned the weakness that came from that: Napoleon, in the back of the emerging French nation-state, was able to conscript millions of patriotic soldiers, invaded the Holy Roman Empire, and ended this 1,000-year-old institution.

Modern Germany

Napoleon eventually lost because all other countries united against it. But the shock of the invasion made it clear that the polities of the HRE had to unite or die. These small polities didn’t have a religion in common, but they did have a language. Larger polities started forming around German and the Germanic culture, driven by the new concept of nations that had appeared in the 1700s and exploded in the 1800s (thanks to the printing press).

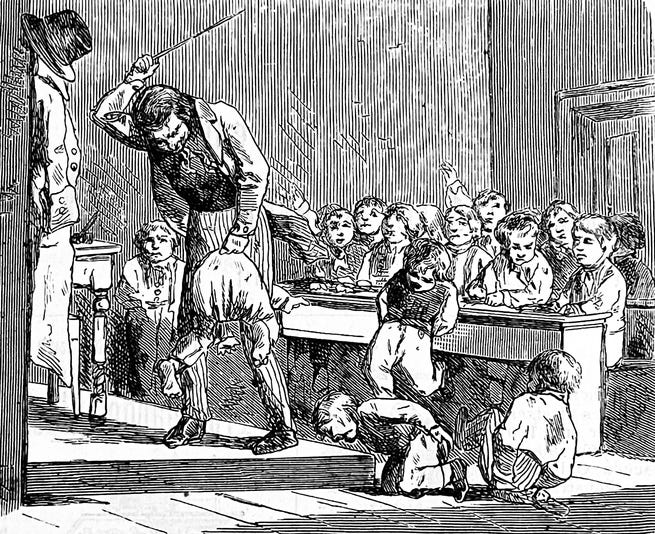

Germans wanted to build a German nation around the trauma of Napoleon’s invasions; they obsessed about that never happening again. But who would lead that unification? At the time, the biggest contenders were the Austrian Empire and Prussia, followed by the secondary players of Bavaria, Saxony, and Württemberg. But the winner was Prussia, led by Bismarck. Prussia overhauled the military, modernized the economy and its industries, played its diplomatic cards well, and created the modern school system to shape citizens into productive tools for the state and obedient soldiers.9

This eventually led to the unification of Germany in the 1870s. It’s not a coincidence that the birth of that nation state was signed in Paris in 1871, after Prussia won the Franco-Prussian war: It closed the wound opened by Napoleon 70 years earlier, and closed the storyline of German people, initially humiliated by France, but united by it.

This is how we reach this map:

Lebensraumed Out

Since German [the language and culture] was the main vector for Germany [the polity] to form, Hitler just went one step further. He used Germans outside of Germany to expand the country.

Hitler:10

Step 1: Austria, since you’re not part of the Austro-Hungarian empire anymore, you might as well join Germany? OK, great, let’s do the Anschluss and unite!

Step 2: Hey Czechoslovakia, see all these Germans in the mountains around Bohemia? We need to protect them. OK, now this is part of Germany, thanks!

Step 3: Uh oh, looks like you’re a bit unprotected now, Czechoslovakia… It turns out Germans occupied all the easily-defensible mountains, and now your plains are surrounded on three fronts. Who would have thought?!

In 1939, soon after taking over the Sudetenland, Hitler annexed all of present-day Czechia.

Step 4: Guess what other region is ALSO surrounded by Germans and can be attacked from three places? You wouldn’t believe it! That’s right, Poland!

And that’s when France and the UK said Basta and intervened. We know the result: Hitler lost, Stalin demanded western Poland for himself, and this part of Germany—which had not really been part of the Holy Roman Empire and had only become Prussian a century earlier—was given to Poland.

The Soviets kindly invited Germans to move out of the land.

Hitler's strategy had backfired. Fuck around, find out. Across Poland, the Sudetenland, and other regions, Germans were not welcome anymore. They were raped, killed, expelled, or fled the massacre before the Soviets could catch them. About 12,000,000 German civilians were expelled across Eastern Europe—that is, force stripped of their homes and property and citizenry for the crime of speaking German, ethnically cleansed. Soviets might have raped up to 2,000,000 German women.11 Between 500,000 and 1,000,000 Germans died during this expulsion: many killed, some starved to death. It was, until that point, one of the largest ethnic cleansing in history, if not the largest.

German shrunk along with Germany.

Putin has been using the same strategy as Hitler but with Russian in Ukraine. He first took over the areas where Russian was widely spoken, and then used the defense of Russians within Ukraine to launch the broader attack.

How Did German and Germany Form Then?

It’s time to answer our questions.

Germanic tribes started around what is Denmark, southern Sweden, and northern Germany today, and moved south during Roman times. They eventually clashed with the Romans, and through centuries of interactions, cultural mixing gave them institutions and technology, which they eventually used to conquer parts of the Roman Empire when it was weak.

There had been no serious German-speaking state until Charlemagne created the Holy Roman Empire, and even then this was not a German state: A big chunk of it ended up adopting the local Latin vernaculars—what would become French and Italian. The remaining Holy Roman Empire contained many languages, and the language of rulers was Latin for 700 years of the empire.

German and Germans expanded not through the state, but through trade, culture, and religion:

In the North Sea and the Baltic, via trade routes, Christianity, and war

Through the numerous internal rivers: Rhine, Weser, Elbe, Oder

By settling eastern regions, frequently by invitation from local leaders

Through the printing press, and its resulting Protestant Reformation

Through nationalistic consolidation after the crisis of Napoleon

Through state-mandated education, even before there was an actual German state!

This is not how it worked for other countries in the region. For example, France and Spain united politically much before they united linguistically. Their governments had a heavy hand in forcing the language through their populations, as a means to strengthen the concept of nationhood.

German generally expanded first, and the polity followed. Hitler just took it to the extreme.

But what had limited the expansion of German throughout history? Mountains and neighboring powers.12 The same thing happened again: Hitler overplayed his hand, and the powers that had always boxed Germany in, boxed it in again, this time into submission. Germany lost a big chunk of its land—and its power.

But not all of it. Today, Germany is still one of the richest countries in the world. Why?

And why is it federal?

Why was the Holy Roman Empire such a weird and fractured country that nevertheless survived 1,000 years?

Why did the printing press and the Reformation emerge in Germany, of all places?

What’s going to happen in the upcoming elections?

After them?

These are the questions we’re going to answer in the upcoming series (some premium articles). Subscribe to read them!

Throughout this series of articles, I use the term “Germany” to refer to the land that would eventually become Germany. Over most of history, that means “a big chunk of the Holy Roman Empire”, and as a result I frequently mix the terms “Holy Roman Empire” (HRE) and “Germany”. I tend to use HRE when I really refer to the HRE, and Germany when I refer to “what would eventually become Germany”.

The tribes and their names were not continuous. E.g. in the 5th. century it was kind a "lifestyle" to call oneself "hun" for some decades (even Romans did that).

And maybe Eastern Europe, but that doesn’t fit with the language maps, so my best guess is that these peoples were either bundled into Germanic tribes by Romans, or originally came from the region I mentioned above, even though they moved into Eastern Europe.

There’s still debate about the fall of the Roman Empire. The main theories are that it was weakened from inside because its entire economic model was based on expansion (and when it couldn’t expand anymore, civil tension increased), a takeover from the Praetorian Guard (with similar causes as what I just outlined), vested interests growing stronger over time, the cost of the overextension of the empire, the climate becoming worse, and more. What’s clear is that the empire’s weakening from inside was one of the major causes.

Early on, the realm was only referred to as the Roman Empire. "Holy", in the sense of "consecrated", was used only starting in 1157 under Frederick I Barbarossa. The term was added to reflect his ambition to dominate Italy and the Papacy.

There was heavy road transportation too, it wasn’t just rivers. But I assume riverine trade was much more prevalent in volume, since it would be 10-40x cheaper than by road.

Venice, Genoa, and Byzantium are examples of an equivalent concept in the Mediterranean.

From Wikipedia: In 1534, the Luther Bible was printed by Martin Luther, and that translation is considered to be an important step towards the evolution of the Early New High German. It aimed to be understandable to an ample audience and was based mainly on High German varieties.

He based his translation mainly on this already developed language, which was the most widely understood language in the region at this time.

He spent much time among the population of Saxony researching the dialect so as to make the work as natural and accessible to German speakers as possible. Copies of Luther's Bible featured a long list of glosses for each region, translating words which were unknown in the region into the regional dialect.

The publication of Luther's Bible was a decisive moment in the spread of literacy in early modern Germany, and promoted the development of non-local forms of language and exposed all speakers to forms of German from outside their own area.

The idea of school didn’t come out of nowhere: Prussia had developed a similar model 50 years earlier, in the mid-1700s.

he idea was older than him though. It emerged during the 19th century, at the very time when all these nation-states were emerging left and right. This idea survives in some places in Germany to this day.

Soviets were not the only to rape. Western Allies and even German soldiers also raped German women, but scholars agree that the vast majority of these rapes were performed by Soviets.

German could not expand in latinized regions and had a hard time competing with Hungarian and Czech, but it expanded more freely in north and northeast areas that were less settled, with less defined civilizations early on.

Small correction: the Anatolian origin for the Indo-European languages has been thoroughly debunked. They instead trace back to the Yamnaya of the Pontic Steppe, north of the Black Sea c. 5000 years ago.

What a lovely coincidence (or not!) that this post's visual style features Prussian Blue 💙 - a color with such deep roots in German history, having been discovered in Berlin back in 1704. The rich, sophisticated hue became one of the most important pigments in European art history, much like how German culture influenced the continent. If you're curious about this fascinating pigment, there's quite an interesting story behind its accidental discovery and how it revolutionized painting! ✨