The Ghost of Poland’s Past

Widać Zabory!

Follow-up article: Poland’s Priorities Today

This is the ghost of Poland’s past:

The split inside the country is so stark and common on maps that Poles have an expression for it: widać zabory, “You can see the partitions”.

Why is there such a partition within the country?

You might have already seen the map below, suggesting an explanation:

This map overlays Polish electoral results with a map of the old German Empire, which lasted from 1871 to 1914. And this pattern wasn’t true for just one election. It’s been true for most of its recent democracy:

The implication is clear: The German Empire caused the western side of Poland to be much more… something. But what exactly? And why? Election results, GDP per capita, population density, labor participation rate, religiosity, crime, air quality, urbanization, infrastructure, language… Even random things like the number of deer or boars, alcoholism, industrialization, the number of bathrooms, the age of buildings, tombstone inscriptions, AIDS… Why do old 19th century borders influence these things? Why are these areas different in certain factors, and not others? And why are both sections of the country part of Poland now?

The explanation to all these questions involves wars, national struggle for survival, ethnic cleansing, forced migrations, imperial conquests, development economics, and more.

The Ghost of the Past

Normally, I start these articles highlighting how geography explains so much of history. But you can’t see this partition in Poland’s geography:

Yes, the country is somewhat lower and flatter on the side that used to be German, but a look at a topographic map shows you this ain’t so dramatic.

So it doesn’t look like the topography created this dramatic partition, or defined the borders between old Germany and Poland. Maybe we can get a clue from the history of Poland’s borders:

Here’s a slower gif showing the evolution step by step:

Wait, what? Why have the borders changed so much? This map shows which polities Warsaw has belonged to throughout history:

Compare to France:

France is much more defined because it has spent much more time as a unit. The map of Poland resembles the map of Ukraine much more than that of France:

Here’s a static version so you can see in detail which parts of Europe have been Polish and for how long:

And the reason, of course, is the same.

Plain Poland

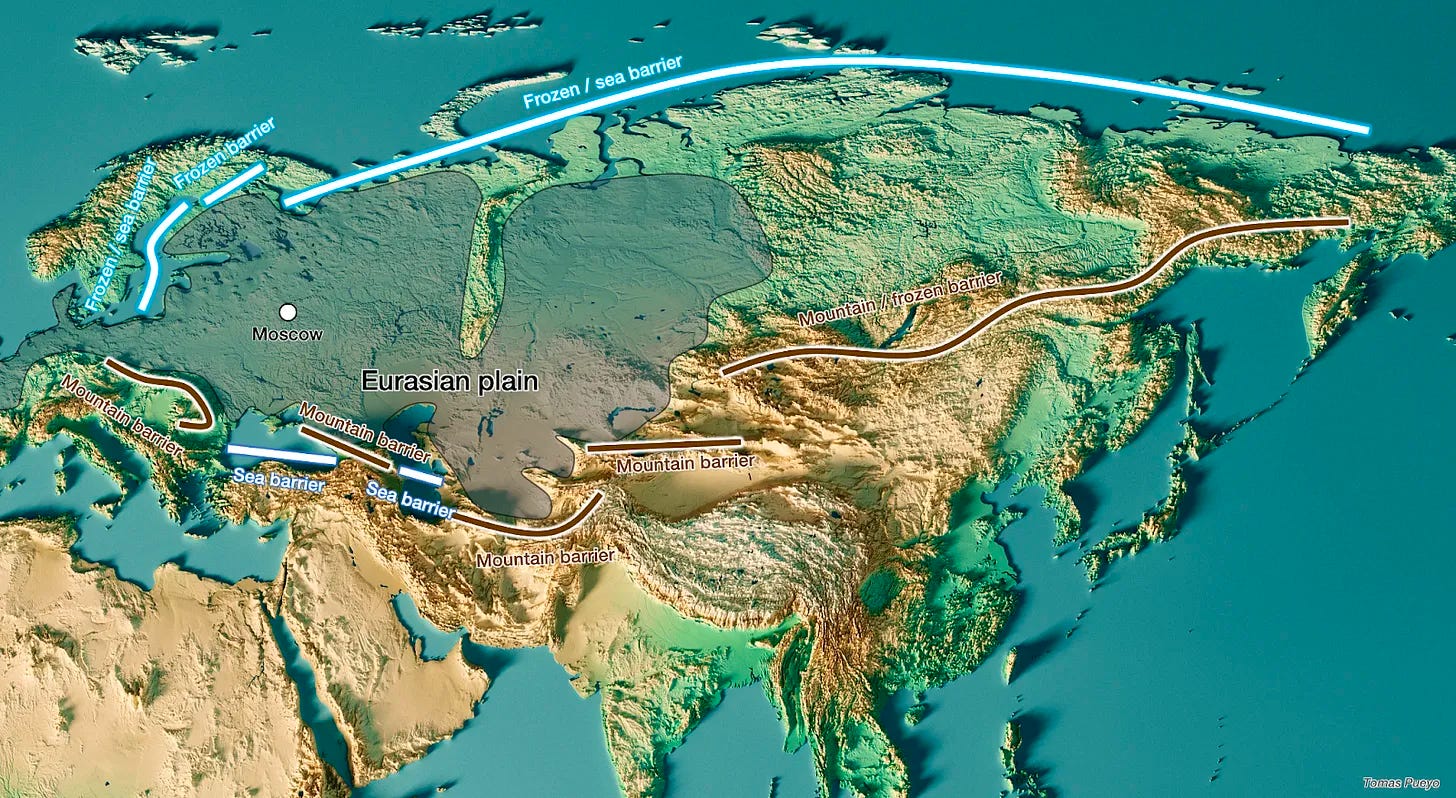

Poland is smack in the middle of the European Plain that goes from southwestern France to Russia—and continues in the Eurasian Steppe all the way to Mongolia.

Poland is not just part of the plain. It occupies the entire plain between Western and Eastern Europe. If you want to go from one to the other, you have to go through Poland.

So people did go through Poland.

You can see that a majority of the threats have come from the east—the massive Eurasian Steppe. This is where the threat still comes from today: Russia.

But you can see that the Germans have invaded from the west (and north, through the Teutons) a few times, too.

And Poland has even been invaded from the sea to the north, by people from the northern side of the Baltic: first the Vikings, then the Teutons and the Swedes.

Despite all these threats, Poland survived for 1000 years, and its most successful was when it was allied with Lithuania to form the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth.

But that left it completely overstretched and overexposed.

That arrangement worked as long as its neighbors were weak, which is the entire Middle Ages and early Modern Period, between 1000 and 1650 or so. But during all that time, Poland’s neighbors were getting stronger and stronger.

As we saw, Russia was slightly luckier than Poland: It had no enemy to the east. So it spent about 250 years securing its eastern flank, between the mid-1400s and the late-1600s.

And why does it not have any enemies to the East? My hypothesis is that the Volga, to Russia’s west and close to Moscow, is the last navigable river that flows south in the Eurasian continent—to the Caspian Sea.

After that, deserts and mountains in the middle of Asia—caused by the Indian Plate hitting the Eurasian Plate—push rivers to flow from the South to the North, so they freeze in winter, making them unreliable. They also run in parallel and so don’t cross each other, which hampers trade. The result is that any civilization emerging here would be disconnected, poor, and not very populous because the land is cold and the technology to work the more fertile areas didn’t reach them quickly.

Whatever the reason, once Russia was strong to the East, it turned to the West. You can see on the map how it conquered land there starting in the mid-1600s up until the 1800s.

We will look into Germany soon, but the short story there is that first the Teutonic Order, and next Prussia pushed from the North and West for centuries, until Prussia became really strong in the 1700s. Austria-Hungary also grew to the south-east. Sweden grew strong in the 1600s.

Look at Europe in the mid-1400s:

Fragmented.

Now look at it 200 years later:

Notice how Sweden, Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and Austria/Hungary/Bohemia are now much more concentrated. Notice also the small green thing to the West that says “Brandenburg”. That’s Prussia growing.

Now look at a map of Europe around 1750:

There are fewer, yet stronger enemies around the Poland-Lithuania Commonwealth, and they are all lurking, eyeing it in the middle, completely exposed.

The Death of Poland

In the late 1770s, the neighboring powers struck a powerful blow to Poland-Lithuania. They got together and wondered: Wouldn’t it be cool if we… just helped ourselves to pieces of the kingdom?

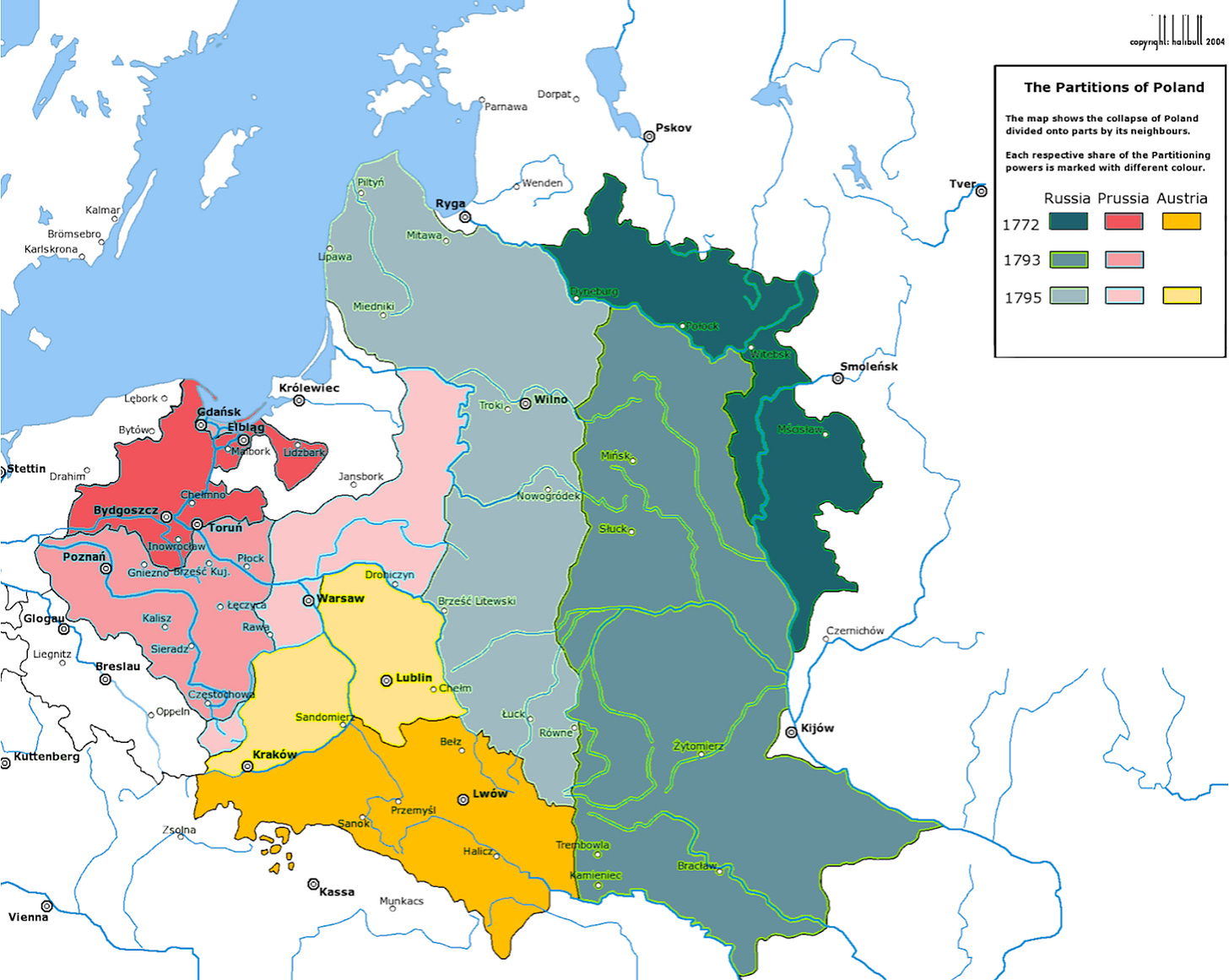

Prussia, Russia, and Austria decided to grab Polish-Lithuanian land in 1772. Attacked on three fronts at once, it couldn’t win. The country lost 30% of its land and 33% of its population, including most of its mines and all of its ports.

By seizing northwestern Poland, Prussia instantly cut Poland off from the sea and gained control of over 80% of the Commonwealth's total foreign trade. And then by levying enormous customs duties, Prussia accelerated the inevitable collapse of the Commonwealth.

Then Prussia and Russia thought: That worked rather well, maybe we should do it again?

21 years later, they each grabbed another piece of the country.

Now only a small piece of the country remained. It would be a shame to leave it at that. Let’s just finish eating the cake. The third and last partition of Poland took place in 1795, and the country disappeared.

After nearly 1000 years, Poland ceased to exist. And given the strength of its neighbors, it would remain occupied or controlled by foreign states for 80% of the last 230 years!

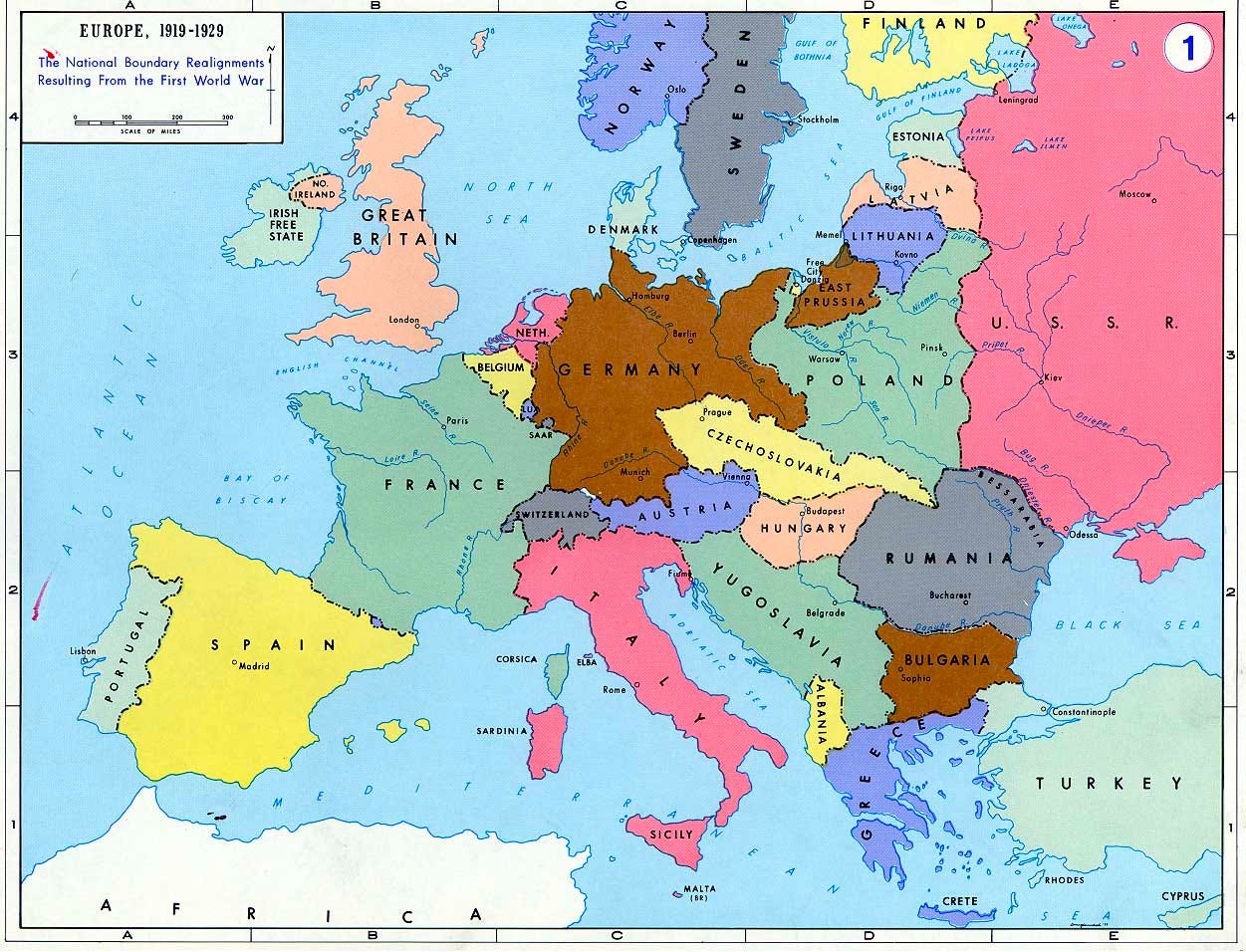

This is how we end up with a German Empire that looked like this in 1871:

But Germany and Austria-Hungary lost WWI and Russia was in free fall due to its Communist revolution, so after the war, in 1918, the Allies created Poland again—nearly 125 years after its disappearance.

The Resurrection

For all this time, Poland was occupied by foreign powers that were completely different in their approach to development. The map from the beginning highlights the Prussian / German part, in contrast with the Russian and Austro-Hungarian parts. But if you squint, you can also see differences between the Russian and Austro-Hungarian parts:

The Austro-Hungarian part contrasts with the Russian part in some aspects, such as religiosity and economic development. Here’s a map shared by Szymon Pifczyk1, showing the share of farmland dedicated to subsistence farming:

According to Szymon, in Austro-Hungary, farms could be split between all children, which meant the Poles there ended up with thousands of really small farms. In Prussia, for example, only the oldest son inherited the farm. You can see the stark difference on Google Maps:

Indeed, the Austro-Hungarian Empire left its traces.

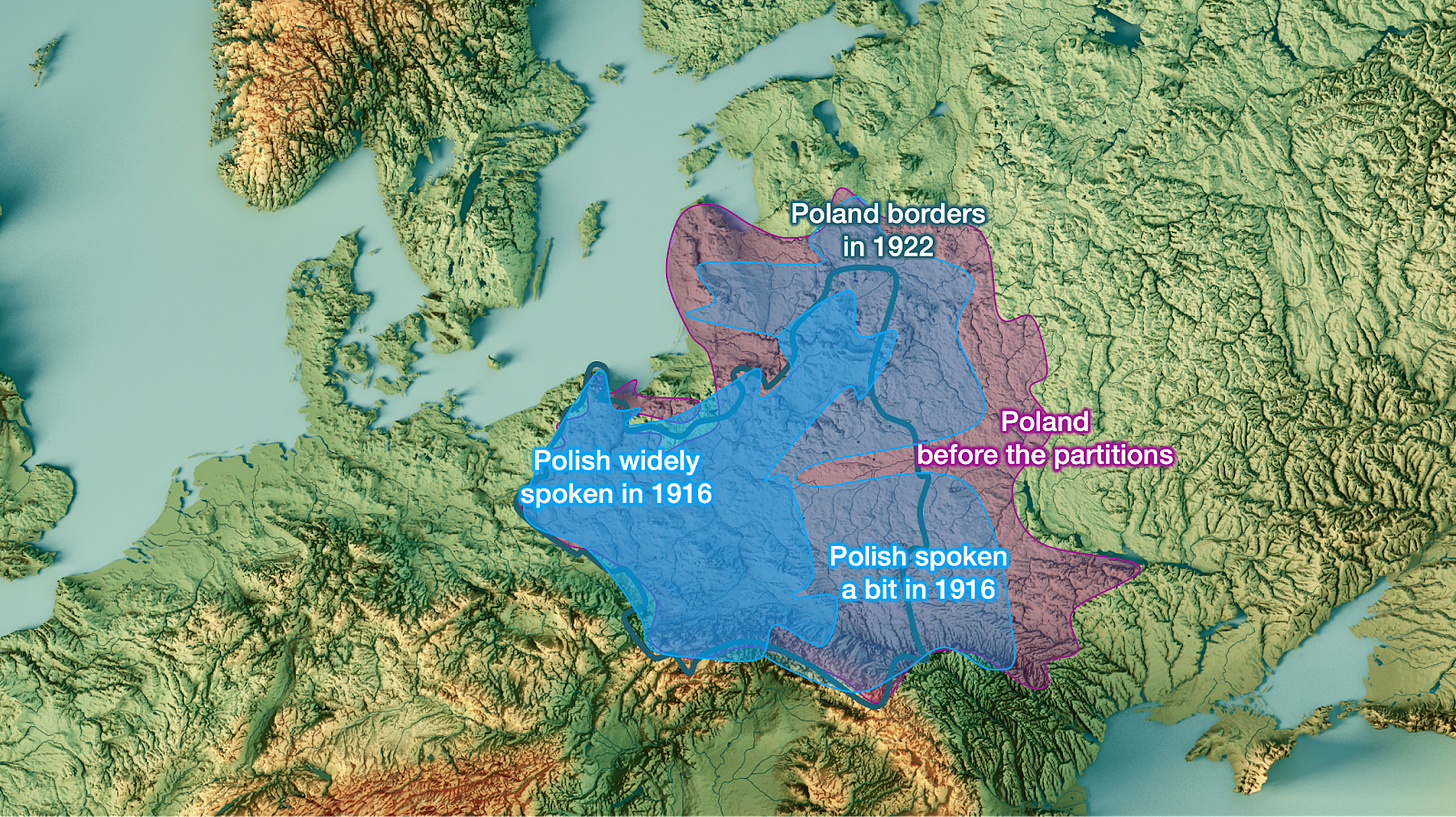

But when the German and Austro-Hungarian Empires lost WWI, Poland reappeared. How did that new Poland compare to the Poland from before?

Poland’s border to the south and west was broadly the same: That’s where Germany and Austro-Hungary were. They basically returned the lands taken from Poland in the late 1700s. But Poland lost a lot of land to the east compared to its pre-partition borders.

Part of it was linked to ethnicities: Poles lived more in the western parts of the Poland-Lithuania Commonwealth.

Part of it was politics. This is what Europe looked like just after WWI:

The Allies, who won, created many countries to weaken their rivals Germany and Austro-Hungary. They were especially aggressive with the Austro-Hungarian Empire, and split it into Czechoslovakia, Austria, Hungary, Yugoslavia...

But Russia didn’t lose WWI. It was on the Allied side. It just fell into a revolution, which bled into a civil war. So the Allies were drawing lines on a map of what would become the borders of future countries on the Soviet side. At the time, it was fashionable to build countries along ethnic lines. Here, you can see languages:

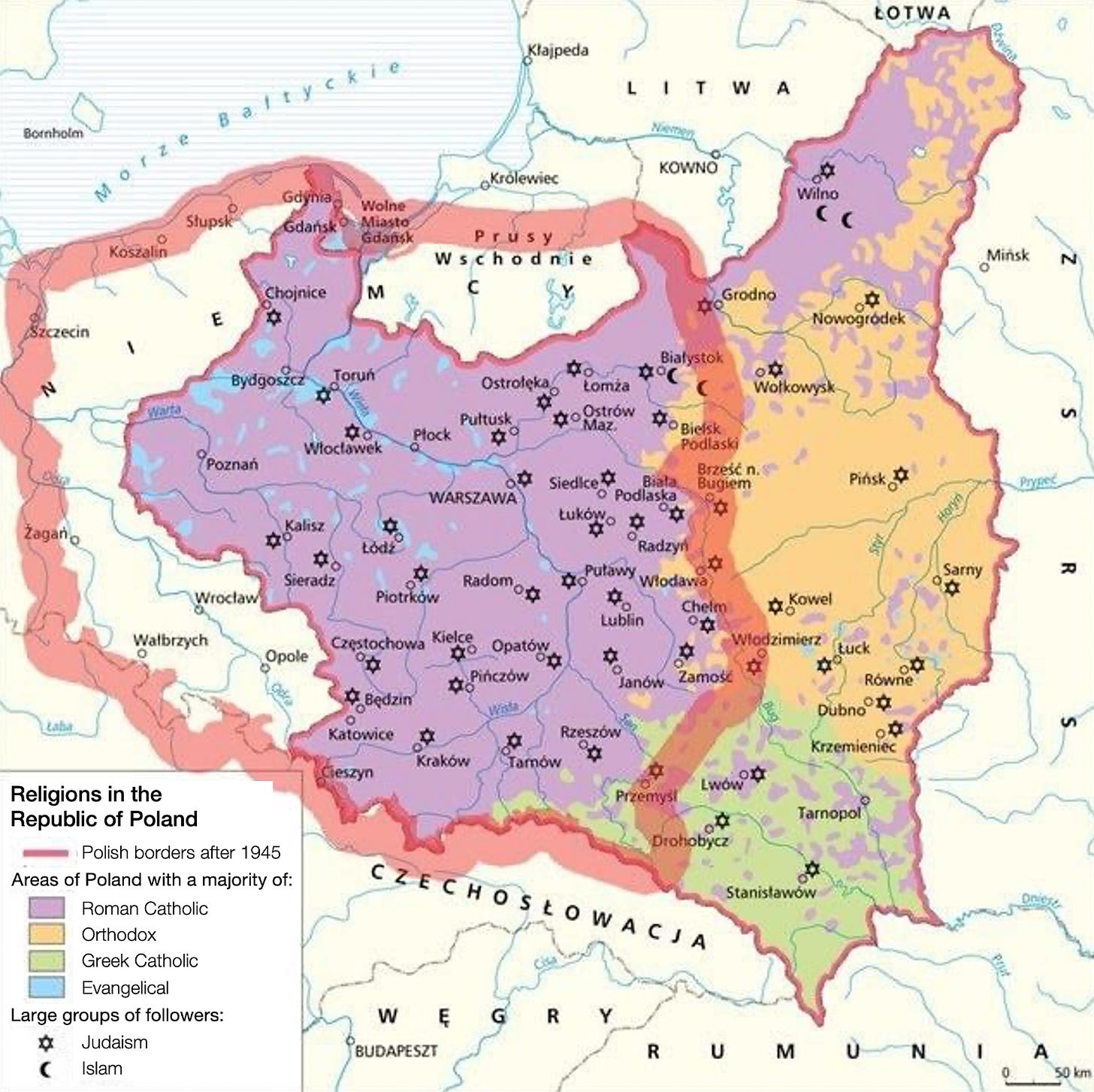

And here religions:

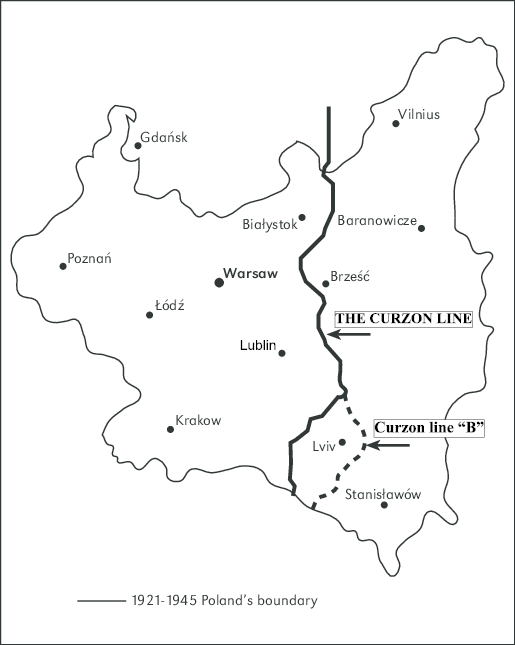

So the Allies proposed the “Curzon Line”, named after the British Lord Curzon who authored it:

But since the USSR was weak due to the revolution and civil war, countries like Latvia and Lithuania took advantage of the situation to claim their independence from the USSR. Poland fought a war with it and expanded east further than the Curzon Line—which expanded Poland more than the Allies had anticipated when drawing the Curzon Line, but still not enough to recover all the lands lost in the 1700s.

Then WWII happened, and Germany and Russia did as they had 150 years earlier: They split Poland again. The USSR basically retook everything east of the Curzon Line, and Germany took the rest.

When Germany lost WWII, something similar to after WWI happened: Germany was penalized and had to give up its Polish lands.

The big difference is that this time, the USSR was powerful. It had won, and it didn’t want to give up its conquered lands.

The swap after 1945

The result was awkward: Poland was now split in half just because the USSR happened to be powerful. The Allies tried to get the USSR to give the lands east of the Curzon Line back to Poland, to which Stalin responded:

"Do you want me to tell the Russian people that I am less Russian than Lord Curzon?"

So that was that.

The Allies decided to weaken Germany instead and give Poland a bunch of German land to its west, in red below:

The land that Poland inherited had been German for centuries, so was ethnically German. Now that this land belonged to Poland, the Germans living there were kicked out. The flight and expulsion of Germans from what was eastern Germany prior to WWII began before the Soviet conquest of those regions from the Nazis, and the process continued in the years immediately after the war. About 8M Germans were evacuated, expelled, or migrated by 1950.2

Meanwhile, 1.5–2 million ethnic Poles moved or were expelled from the previously Polish areas annexed by the Soviet Union. The vast majority were resettled in the former German territories. But because many more Germans left than Poles arrived, the “recovered territories” initially faced a severe population shortage.

Although all this ethnic cleansing after 1945 was bad—and the hundreds of thousands, even millions who died in the process even worse—the swap was good for Poland geostrategically:

The country became much more compact, so easier to protect.

It gained a much larger access to the sea, good for trade and also easier to protect than land.

It gained access to the Oder River, great for inland transportation and trade.

It gained from the Germans a highly developed industrial base and infrastructure that made a diversified industrial economy possible for the first time in Polish history.

Poland became very ethnically homogeneous, as 98% of the population was Polish in 1950.

The “recovered territories” (red above) are interesting. A very long time ago, they had been Polish. Then Germans took them over, while Poland gravitated eastward. Why? Because Germanic people were becoming richer and more populous to the west, and they were settling the Baltic and the eastern part of Germany. For Poland, there was more pressure from Germanic people from the west than from Slavic people from the east.

All these changes resulted in a patchwork Poland in 1945 based on its past occupations:

Which we can see on some maps to this day. For example, notice the difference between the parts that were German for centuries (in blue) with the ones that were only German for about 150 years after the first partition of Poland (red):

Each one of these maps tells us something about Poland’s history. Like:

Poland has many more houses dating back to the German periods than to the Russian or Austro-Hungarian periods—in these regions, housing dates from the Soviet period or later. That’s because of a combination of factors3, but the main reason is that the buildings in the German parts were brick-and-mortar, while they were wooden in the east, and also because the population in eastern part ballooned after WWII, but didn’t in the west.4

The blue part was German for centuries. The people who are there now are not Germans (they mostly left), but Poles who moved in. They tend to be less religious than the Poles in the red region: Although the red region had been German between 1772 and 1918, the population there was Polish. They didn’t move when the Germans left. It’s much easier to stop following your religion when you move, as you don’t have your social circle to enforce it. I assume there was probably also some sort of self-selection, where those who are willing to move are less bound by tradition (and religion) than those who stay.

The German Empire put a strong emphasis on education, so the populations in the blue and red area were highly educated. Then, the Germans from the blue area left, and those who replaced them were from the part that had been Russian to the east, which had less education. Meanwhile, the Poles who were in the red area and had been educated during the German Empire era maintained that education, so the red area is the one with the most education for Polish farmers.

Poland’s Ghost Today

When the Poles refer to widać zabory, or you can see the partitions, they don’t mean you can see how Poland is partitioned today, but rather you can see today the partitions made by foreign powers 250 years ago.

The main partition is between the part that used to be German and the rest, the Russian and Austro-Hungarian parts.

The German part had more infrastructure and buildings left by the Germans—probably because Germans built more, and certainly because they weren’t destroyed during the war.

For the same reason, the buildings in the west are older than in the east.

Since a majority of eastern buildings were built during the Soviet era, they have more asbestos, a common building material at the time.

According to Szymon5:

The east is more rural, and when it underwent a construction boom post WW2, the rural populations still didn't feel like they wanted to use the restroom in the house. So many of these houses have outhouses.

More Germans left than Poles arrived to replace them. These Poles clustered in cities:

So to this day, the formerly German part of Poland seems emptier:

But it isn’t really emptier. Population is just more concentrated. You can even see the effect of the different partitions here: The parts that had been German for many centuries had few Poles in 1945, so when the Germans left, the incoming Poles clustered in cities and left many spaces empty. Meanwhile, the parts that Germany had taken over in the late 1700s had both Poles and Germans. These areas were more widely populated in 1945, and remain so now. Here’s a map showing how spread the emptiness is in the most German areas:

According to Szymon, in the west, all farmland was nationalized and large-scale state agricultural farms were created, so people simply couldn’t settle, grab plots of land, and start cultivating them. Immigrants from the east had to work in these large state farms. Meanwhile, in the east, small farmers remained.

The Poles who went to the German parts went to cities and built more industry, either from scratch, or using the intact German stock:

The previously-German side is more entrepreneurial—probably because the Poles who moved to German lands were self-selected to be more entrepreneurial.

Since there are fewer people, and they live more in the cities in the formerly German parts, there is more nature there, and so more boars and deer.

Since the Poles who moved to German parts self-selected as more adventurous, they are closer to Germany, and they are less rooted than their counterparts in eastern Poland (so their ancestral social circles are not around), they tend to be more progressive. They are less religious and more accepting of new social mores.

Maybe because the German part is more urban and less traditional, it has more crime and more AIDS.

While the east has less economic opportunity because it’s more traditional and is farther from Germany:

And since the west is richer, young people emigrate there for new opportunities:

It’s clear how all these differences can create different political perspectives:

For example, it’s logical that the more entrepreneurial, younger population of the west, who is also closer to the rest of the EU, was more excited about joining the EU than the more traditional part that is closer to Russia:

The Future of Widać Zabory

Luckily, many of these differences are shrinking over time.

It’s somewhat harder to see the partition in the most recent parliamentary elections of 2023:

Church attendance has dropped throughout the country in recent years, becoming more uniform. Infrastructure, like railways, is now better distributed.

Warsaw, the capital, is in the middle of the formerly Russian part of the country, and an engine of development for the east. A different inequality takes over between urban and rural land.

The ghost of Poland’s partitions are like the scars of old wounds that blur over time.

But these scars remind us of conflicts that are still real for Poland.

What does all this history tell us about Poland’s geostrategic priorities today?

What is in Poland’s future?

What was Poland’s contribution to modern democracy?

How did it come up with one of the first modern constitutions, around the same time as the US?

Why were there so many Jews there before WWII? What can we learn from its symbols?

These are some of the questions we explore in the premium article on Poland.

Thank you Szymon for your maps and your insights!

He wrote a thread about Poland’s phantom borders just as I wanted to publish an article about it a few months ago. We stumbled upon many similar themes, so I decided to wait a bit to publish. I wrote a Twitter thread on it, and he offered to fact-check my article. I incorporated some of his maps into this piece, and added more through his edits. I like his content, and if you are interested in Poland’s phantom borders, you should follow him.

From Wikipedia: About 100,000 German civilians died in the fighting prior to the surrender in May 1945, and afterwards, some 200,000 Germans in Poland were employed as forced labor prior to being expelled. Many Germans died in labor camps.

The eastern part got leveled in WWI while the western part was unscathed. In WWII, the eastern part did not suffer too much, but the western part suffered as Germans tried to stop the Red Army.

According to Szymon Pifczyk.

He kindly fact-checked this article. Thank you Szymon!

Incredible story. I've heard and seen this before, but never in this level of detail. What was done to the Poles over the centuries is something that no people should ever experience. I wish them well in their goal of fortifying their country against future aggression from the east and hope that their allies to the west stay true to our shared values.

You can also notice the territory around Białystok (north-eastern part), than in 19th century was direct part of Russian Empire, not Congress Poland. Białystok was kind of Russian Hong-Kong - the gateway between Poland and Russia where all trade was going (esp. textiles) and a lot of Polish companies created outpost to avoid duties. And it's also still visible on some maps.