The Core Formula of Internet Businesses

LTV > CAC, or what other assets outside of network effects can businesses use to create massive Internet businesses

Of these two companies, which one would you invest in? In which one would you want to work?

In last week’s free article, I explained why network effects companies like aggregators and platforms account for 70% of the value created in tech. Network effects make your revenue look like the company on the left, at least for the beginning of the S-curve. The CEO of Spotify knows this, and that’s why he won’t take down Joe Rogan, as we saw in last week’s premium article.

But where does the other 30% come from?

I explained that companies going direct to consumers are not it: they’re usually bad businesses because they’re exposed to a lot of competition. Competition, in general, is as bad for business as it is good for customers.

So what kind of business doesn’t have network effects, and yet doesn’t have too much competition?

These are graphs of revenue. You can see that the top line is growing exponentially on the left—it’s accelerating—but it’s slowing down on the right.

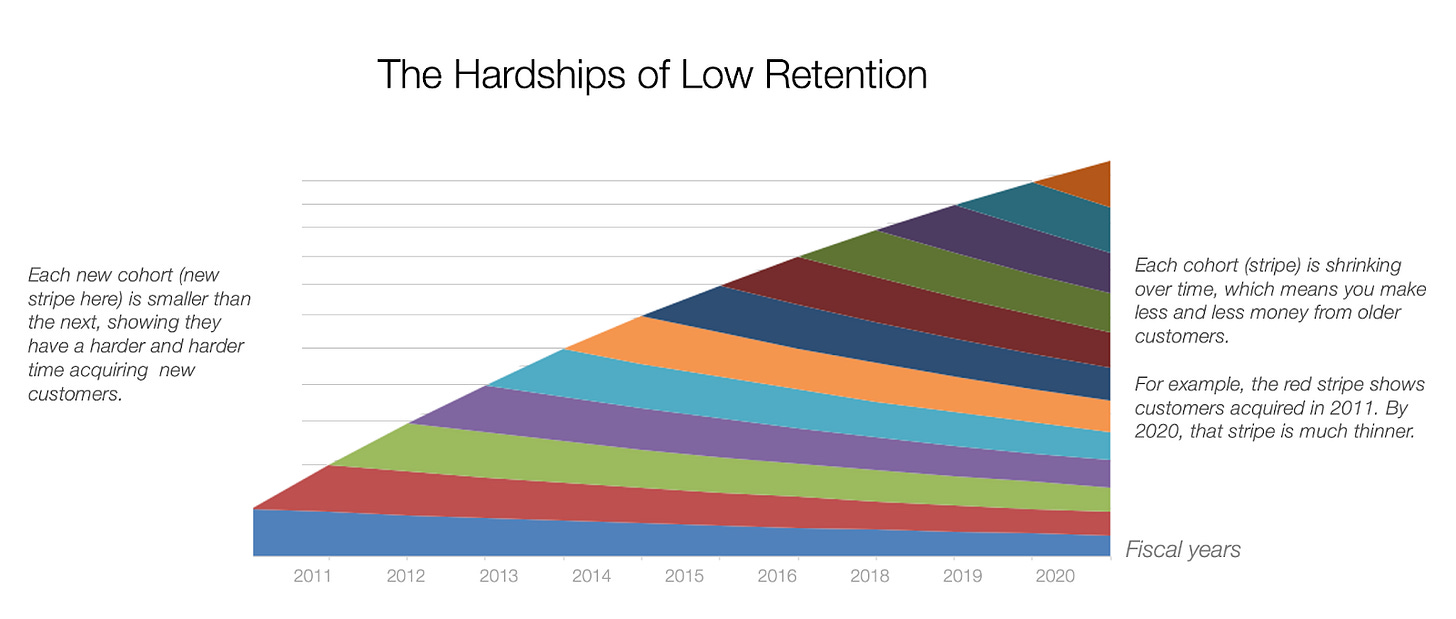

These graphs are what’s called cohort-based revenue. It means they show the revenue coming from groups of people who joined at different times. So what’s going on? Let’s start with the right.

The Hardship of Low Retention

Take the 2010 cohort (the first blue stripe at the bottom). Those are all the people who joined in 2010. After a year, in 2011, the revenue they contribute is smaller (the blue stripe shrinks). Then the next year it’s smaller, and smaller, and smaller. This is one of the two big things happening.

The other is a reduction in the number of customers they can acquire, which you can see as the area between gray lines compressing. As we saw in the previous article, in general it becomes more and more expensive to market a product to new customers over time. The ones that are inclined to find you will do so early on. They are cheap and easy to market to. As you become more mainstream, and then try targeting laggards, it’s more and more expensive to market your product to new customers. We say that your Customer Acquisition Cost (“CAC”, the cost of acquiring one more customer) increases over time.

If over time:

Every cohort shrinks; and

Every new cohort is more expensive than the previous

What you get is revenue that slows down its growth, until the accumulated shrinking of past cohorts becomes bigger than the size of new cohorts, which is ever shrinking.

The bigger the company is, the less it can grow. Eventually, the company plateaus in growth, and even starts shrinking.

A good example of this is Casper. Casper sells mattresses. The problem with mattresses is that you don’t usually buy them more than once every ten years. So retention year over year is nearly zero. By the time you’re shopping for a new mattress, you’ve likely forgotten the brand you bought it from, and you’re going to survey the market again anyway. Here again, retention will be very low.

That means that Casper has a hard time making a lot of money from a customer they acquire (an existing cohort), so it needs to be constantly getting new customers. But, as we saw, that becomes harder and harder, because marketing expenses usually grow as new customers are acquired. And your marketing costs also grow because new competitors emerge: Tuft & Needle, Purple, Leesa, Helix, Simba, 8h Sleep, Saatva… The result is that companies like Casper have a very hard time surviving.

Now compare this to the graph on the left.

Positive Retention

Look at the dark purple stripe at the bottom, or the light blue one.

These stripes grow every year. The same thing is true for the green, the yellow, and the red stripe. Each one of them gets bigger over time.

This is what we call a net positive retention. Your retention year over year, instead of shrinking your customers, is growing them!

If your cohort doesn’t change in size, we say retention is 100%. If it shrinks over time, it’s below 100%. 80% means you lose 20% of your business from a given cohort every year. If it increases, it’s above 100%. For example, 140% means you grow a cohort by 40% year over year. We say you have a net positive revenue retention.

This has two additional advantages:

Because each cohort grows over time, the revenue you can make from each one of them grows over time, which means you can afford to spend much more money to acquire news customers. The CAC (Customer Acquisition Cost) you tolerate is higher and higher.

Because your customers use you more and more, you have more and more people talking about you better and better. This word-of-mouth effect actually makes it cheaper to add new customers. Your CAC goes down.

If you combine those two factors, you get the exponential curve:

Now, what kind of businesses have net positive retention?

SaaS

As a consumer, when do you buy more and more and more from the same business? It seldom happens. Usually, you buy from a business, and over time either your consumption stays the same or shrinks. You don’t eat more food or wear more clothes over time, for example. You might have periods of more or less consumption, but it doesn’t keep growing.

This is not true for growing businesses: as they grow, their providers grow with them.

Not only that, but a business might try a tool from a new provider, and as the tool proves useful, the company uses that tool more and more, therefore increasing how much they pay to the provider.

This typically happens in some SaaS companies (“Software As A Service”). These companies sell tools to other companies and charge them for usage.

Take, for example Slack, a tool to chat with co-workers inside and outside of your company. Slack made it free for anybody to use it as consumers. Some people use them in their private life, and then they start using it with co-workers. As that happens, eventually the IT department notices, and buys licenses for them from Slack.

Notice what happened there: their CAC is very low, because they didn’t need to spend much on marketing or sales.

This is the beginning of the cohort. But since the tool is useful, more and more people start using it in the company. So IT buys more and more seats from Slack every year. The net retention is positive, and every cohort grows.

There’s an additional benefit to SaaS: once a company uses a tool, changing it is hard because it’s embedded.

Embedding

A company needs to assess in depth the pros and cons of different tools, make sure that the benefits of changing outweigh the costs, spend the time and money to extirpate the existing tool, the time and money to insert the new tool, and ask everybody to change their habits and learn a new tool. It’s such a pain that most companies don’t do it, even if a new competitor comes around with a better service. It needs to be 10x better for a company to switch quickly. So net retention is very high.

Note that a SaaS tool that is not embedded might be growing fast, but it’s at a major risk of disruption. Another tool can come around, and if it’s better and switching costs are low, the customer might change providers. In fact, there are companies that make it their business to reduce switching costs. The perfect example is Segment.

You’ve probably never heard about that company, but Twilio acquired it in late 2020 for over $3B (cheap if you ask me). Their promise is: “You’re going to embed us into your software, and after that you don’t need to embed anybody else. We’re going to give you a dashboard and you’ll simply switch on and off the access to other companies. We’ll take care of sending the right info to the right company so you can use any external tool you want without the cost of embedding.”

The fact that such a business was so successful, and was bought for so much money, tells you how much of a pain it is to embed new tools into your company, and how much companies want to avoid that (because once you’re in, you’re in for a long time).

Traditional companies such as SAP or IBM made a lot of money this way, but they did so before the SaaS era, when embedding meant physically embedding into your customer (we call this on-premise software). More recently, Salesforce is one of the big players who has won the embedding war. They were one of the early winners of the SaaS trend. Since, all business tools have been opening up to a cloud alternative, because it’s 10x better than on-premise, so worth the cost of replacing the embedded option. As a result, Cloud-Based SaaS is a once-in-a-generation opportunity for new companies to replace old ones and be the ones embedded into their customers, this time servicing them from the cloud.

Zero Marginal Cost

There’s yet another benefit of the SaaS model: because it’s software, the cost of having more and more usage inside a company barely grows. Profits grow much faster than revenue.

All of this is why the SaaS companies that have a good product with net positive retention grow exponentially:

And why the biggest driver of their value is their net revenue retention:

And this is why companies that have an amazing net revenue retention will grow like crazy and are good places to work at or invest in for me.

Note that a good investment depends on the price you’re paying. For example, when Zoom was at a multiple of 70x over revenue, that was very, very expensive. Even if their net revenue retention was high, it didn’t justify the price investors were paying. The key is to find such companies before people know about them, when the market has lost faith in them despite great numbers, or when their future growth has so much potential that the company will eventually be able to grow into its valuation.

So what is the magic formula of the Internet?

LTV > CAC

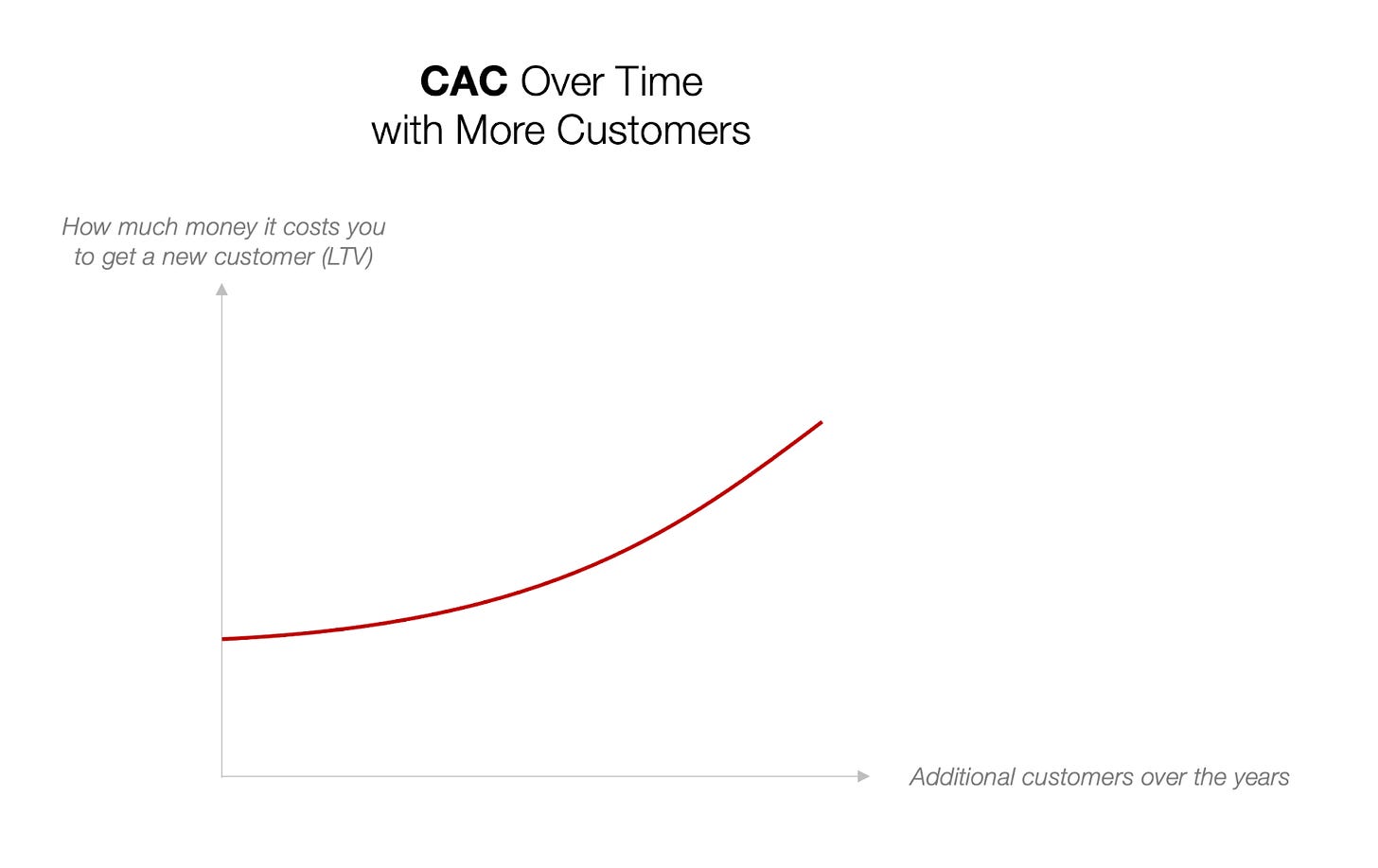

The growth potential of any company depends on its unit economics: how much it costs to get new customers (CAC, customer acquisition cost) vs. how much you get from them (LTV, LifeTime Value).

As we discussed, LTV for a normal business tends to go down as you add more and more customers that are more mainstream and competition increases.

Also, CAC tends to increase because it’s harder and harder to get more customers that are more mainstream, after exhausting the cheaper channels to get customers. And competition also increases marketing costs.

The result is that you’re only going to grow to the size where your LTV is higher than your CAC.

This, of course, is a standard supply-demand curve. Your size is determined by the magic formula of supply and demand, which on the Internet translates into LTV>CAC.

For many normal companies, including Internet companies like DTC (Direct To Consumer), this is the daily challenge. The product teams focus on making the product better so the LTV is higher (hard), and the marketing and sales teams focus on reducing CAC (hard). A competitor that has a slight edge on either can outspend you and catapult you to oblivion.

Here’s what happens instead with platforms and aggregators:

Since LTV goes up and CAC goes down, LTV never meets CAC, and the company can keep growing until it saturates the entire network.

Which can justify, in some cases, massive upfront investments to grow as much as possible, even losing money per customer. That way, these aggregators can grow to a point where the network effects create a massive amount of value, so LTV is high and new customers join more easily, reducing CAC.

So how do SaaS companies look like in such a graph?

It’s not like their LTV is infinite. To take Slack, for example, the total spend that a company is going to have on a tool like Slack is not infinite. But it can grow for years and years, and the client company might keep the tool for years, even decades. So the overall LTV is huge. And it might not go down too fast as they go down market (service smaller, less profitable customers), because the tool can be adapted as it goes to serve new types of companies.

It’s also not like their CAC goes down, like in aggregators and platforms. It keeps going up. But it’s substantially lower than the LTV to begin with, and when the company is good, CAC doesn’t grow too fast because word of mouth kicks in and makes sales easier.

Since LTV is so much higher than CAC for a very long time (LTV>>>CAC), it can keep growing for many years, even decades. As it does, it can keep innovating and adding new tools, which increases LTV. This is why a company like Salesforce is so massive.

Takeaways

If you want to work at a tech company, you should go ideally for an aggregator or a platform, because LTV increases and CAC decreases over time.

Another good option is working at SaaS companies, but make sure:

They have a positive net revenue retention. The higher, the better.

They’re embedded, and it’s hard to get them out of a customer.

I also follow these guidelines for work. But this is for myself, I’m just sharing my thinking process. Remember that you should not take investment advice from me, I’m not a financial advisor. Please consult your financial advisor.

But what, of all of this, is so special about the Internet? Isn’t all of this true for traditional businesses too? Partially.

There are network effects in traditional businesses, but these usually require actual, physical networks: roads, railroads, phone, gas… No wonder each one of these is a massive industry. But there are few of them and they’re heavily regulated.

That’s not true for the Internet: you can create new companies with network effects easily, and you don’t need to ask for permission. Since there are no direct physical consequences, there’s less regulation, so more opportunities.

The other crucial difference is that it costs you nothing to service a new customer. If you have a shop, you need to factor in the cost of goods sold. If you add one more Slack user, you don’t spend anything on that customer.

That means that the variable cost of an Internet company is nearly zero. For most Internet companies, the biggest variable cost is only CAC. That puts them at an advantage.

It also creates an interesting dynamic. Since CAC is the main variable cost, now every company spends up to their entire LTV on acquiring new customers.

That means the most scarce resource for Internet companies is… attention.

And that’s why the Attention Economy is at the cornerstone of everything that happens online. You can’t understand the Internet if you don’t understand the Attention Economy. So let’s understand that next.

If you’ve enjoyed this article, you will enjoy the previous articles about aggregators and platforms, and how we applied those learnings to why Spotify won’t take down Joe Rogan.

Some of the next few articles I’m planning on this series:

The Attention Economy

The Economics of Substack

Other Sources of Advantages for Tech Businesses

How to Regulate Aggregators

Do not take this article as investment advice. This is only for informational and educational purposes. I am not a financial advisor, and you should not invest based on what I write in this article—or any other article. Please consult with your financial advisor before investing.

Excellent article Tomas - your concept of Embedded is a great one. I have called this becoming part of workflow, and it is such a critical value driver for winning SaaS tools. SFDC as the great leading example.

Great article indeed, but it feels too one-sided. If it was that easy to start a network effect company, everyone would do (a lot try!). You need to be the first, fastest, offer more than others do, and continuously improving. We have seen many Facebook predecessors disappear in a matter of months/years. Will FB still exist in 10 years, or will it be replaced by Instagram or TikTok? Since you are very good at researching and analyzing, perhaps do some analysis on high potential network effect companies that "no longer exist" and why they have disappeared. Yahoo, NEtscape, Internet Explorer, MySpace, Skype, MSN messenger are just a few examples. It feels like there is a tipping point... Keep up the good work! 😊