Why Did Korea Split?

The crazy story of a few days that changed Korea forever

This is the first article in the Korea series. For a future article, I’d love to talk with English-speaking South Korean women about fertility. If that’s you or you know anyone who’d be interested in chatting with me, please have them fill this one-minute form.

Happy birthday P!

Korea had been united as a single country for over 1,000 years. Then, in 1945, the US and the USSR split the country in two. But was this unavoidable? It was not! The story could have turned out completely differently if it hadn’t been for an obscure clause on a document, Hitler’s resolve, scientific skill, and a few days of bad weather.

And it all starts here.

It’s February 1945. The Western Allies have liberated France and Belgium. The Soviet Union is knocking at the doors of Berlin. The fall of the Nazis is not a question of if, but when. So Roosevelt, Stalin, and Churchill meet in Yalta, Crimea, to decide the fate of the world.

In the Pacific, things are not going so well.

The US was fighting on every island against Japan; it was bleeding its youth dry on the battlefield. So its most pressing need was for the Soviet Union to join the war against Japan, which would reduce American casualties and accelerate the fall of the empire. The USSR agreed to join the war, but only after the fall of Berlin and some time to prepare. Stalin said: We will declare war against Japan three months to the day after the fall of Germany.

This would end up determining the future of Korea, but none of them knew it at the time.

The USSR accepted under the conditions that Mongolia would become an independent country, and that the USSR would receive some Japanese islands.1 Korea was not discussed.

Officially.

At some point during the conference, Roosevelt and Stalin slipped away from Churchill to discuss Korea.

Roosevelt proposed—behind Churchill’s back—that Korea would be put under the trusteeship of Russia, China, and the US, but not the UK. What does that mean? They would jointly manage it. Stalin agreed that they should share the oversight of Korea, but thought the UK should be included. Details were unclear. If they ever talked about it again at Yalta, we don’t know; there are no records.

Germany surrendered on May 8th 1945.

That set the clock ticking: The USSR would join the war against Japan on August 8th 1945.

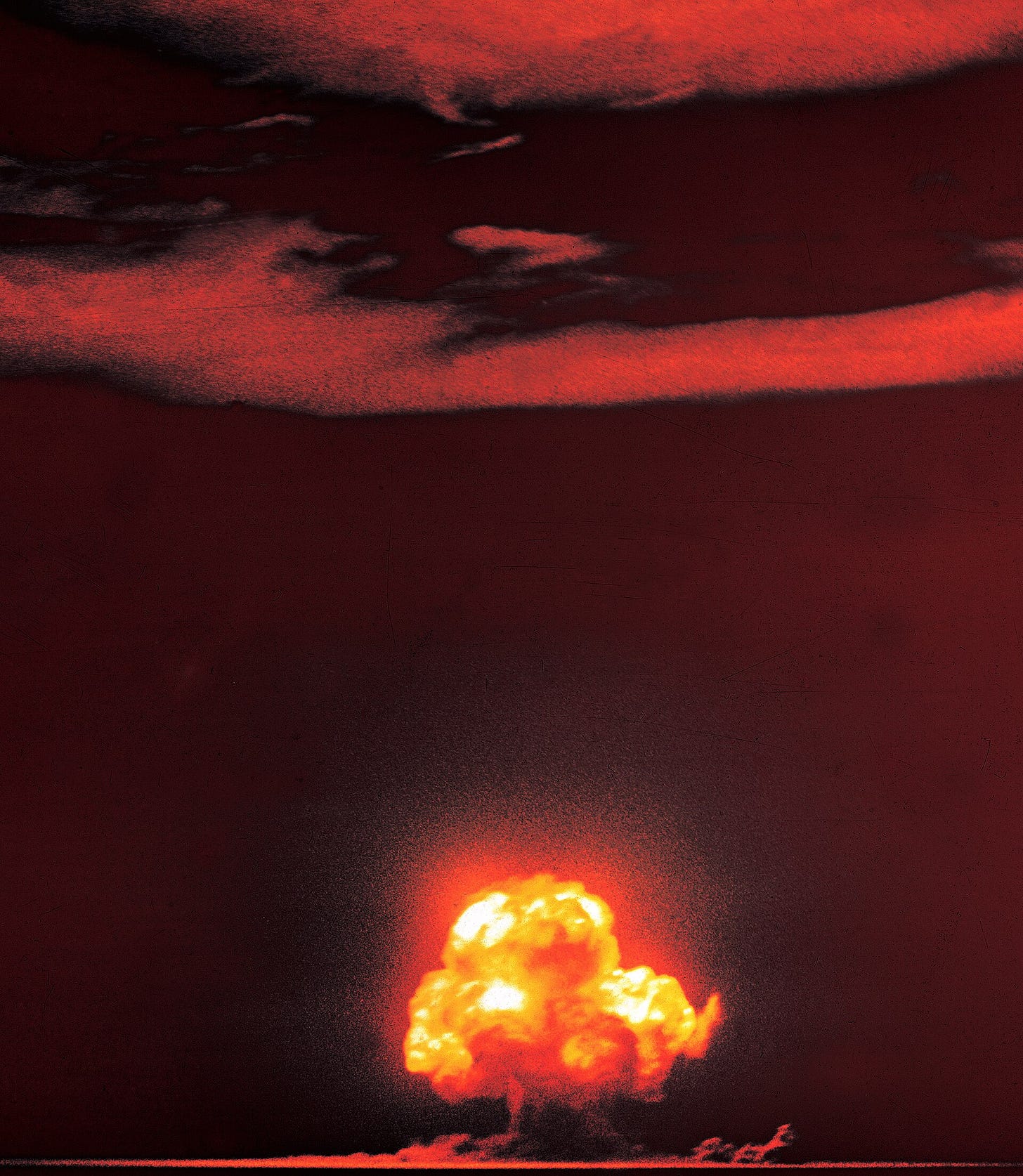

Which would have been convenient for the US. Except for one thing: In the meantime, it developed a huge wildcard. On July 16th 1945, at 5:29 a.m. MWT, the US successfully carried out the Trinity Nuclear Test. It had acquired the nuclear bomb.

Truman, the new US President, learned about it six days later, on July 21st 1945, while he was again meeting Stalin and Churchill, this time in Potsdam, Germany.

Now, the US was racing against the clock: We don’t need the USSR! We can win the war without them! If we drop a bomb on Japan, they will surrender. But we only have 18 days left before the USSR joins the war. We must hurry!

So that’s what they did. Four days later, on July 26th, a nuclear bomb was ready to be dropped on Japan. The US gave Japan an ultimatum: Surrender unconditionally, or else...

13 days left.

On July 28th, Japan refused.

11 days left.

Truman ordered his forces to drop the bomb as soon as possible.

The bomb was scheduled for August 3rd.

5 days left.

But the weather was bad. It continued on the 4th, then the 5th.

On August 6th, 1945 the US dropped the bomb on Hiroshima.

2 days left.

Japan did not react.

Stalin had also known about the bomb: His spies had told him. At that point, the Soviet military was among the most powerful in the world. He calculated that it was now or never: It was the moment to make a move on Asia and take over as much land as possible—just as they had in Eastern Europe, where they had occupied everything all the way to Germany.

So on August 8th 1945, the USSR unleashed 1.5 million soldiers on Japanese-occupied China, Manchuria (Northeast China), Inner Mongolia, Korea (northern part), South Sakhalin & the Kuril Islands (Japan).

They overwhelmed the Japanese.

On August 9th, the US dropped a second bomb, on Nagasaki.

By August 10th, the Russians were already in Korea.

The US freaked out.

It knew that, if it allowed the USSR enough time, it would occupy the entire peninsula and make it a Communist country.

That very evening, on August 10th 1945, the US leadership took two colonels aside and put the destiny of a country in their hands. Their task? Propose a split for Korea to the USSR.

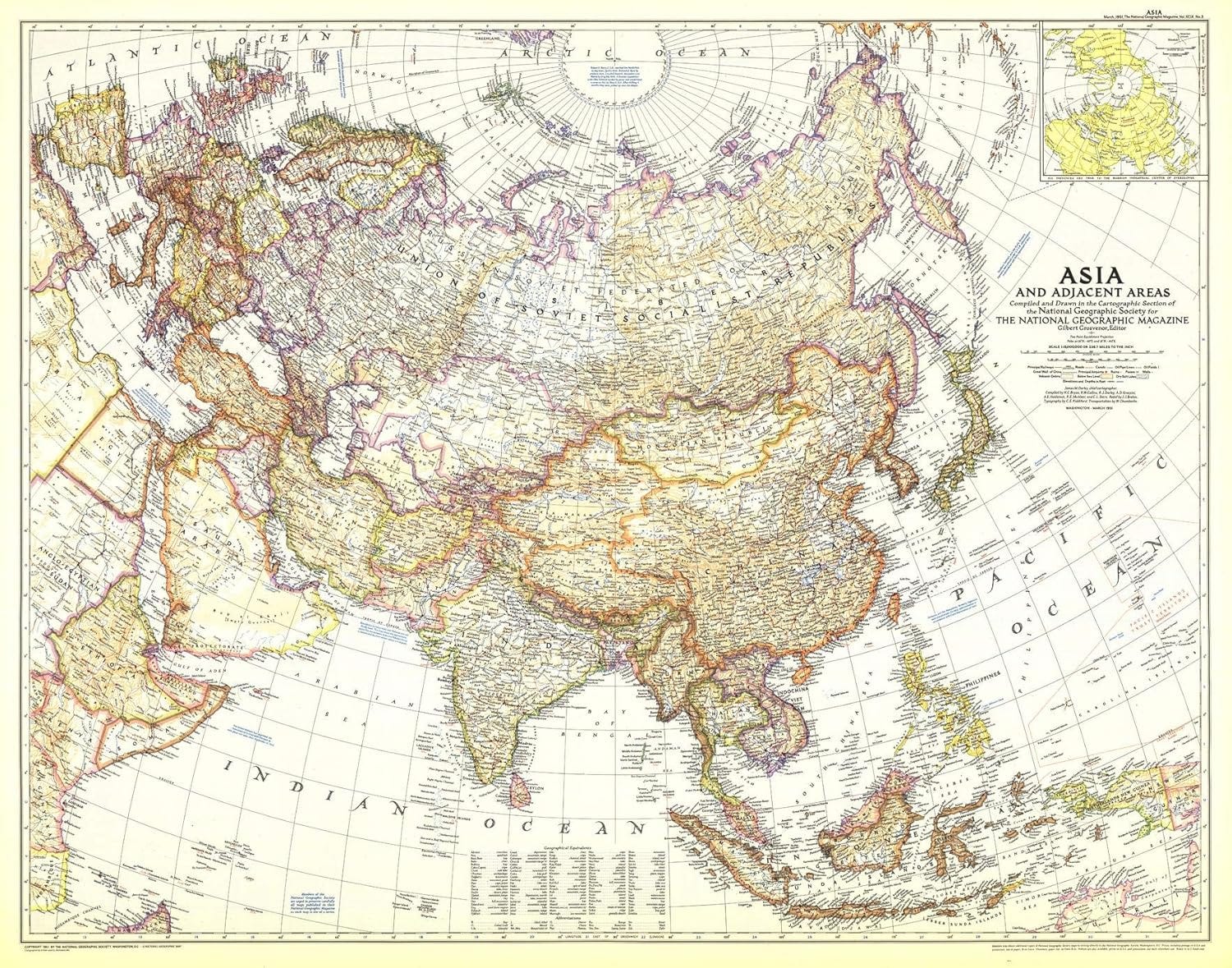

Colonels Chris “Tick” Bonesteel and Dean Rusk did not know anything about Korean geography (!), so they started with a National Geographic map—probably something like this:

This is the extent of information they used to decide how to split Korea.

Holy s**t.

What was their conclusion?

Bonesteel and I retired to an adjacent room late at night and studied intently a map of the Korean peninsula. Working in haste and under great pressure, we had a formidable task: to pick a zone for the American occupation. Neither Tic nor I was a Korea expert, but it seemed to us that Seoul, the capital, should be in the American sector.—As I Saw It, Colonel Dean Rusk

Though some officers argued that they should move the line further north to the 39th parallel, the two officers thought they’d be lucky if the Soviets agreed to the 38th. This is why, on August 14th, six days after the Soviet invasion, Truman proposed to Stalin the 38th Parallel as the place to divide Korea.

On August 16th, to the US’s surprise, he agreed.

The Korean War

Once the USSR and the US had their spheres of influence in Korea, they each put forces on the ground. And a new world began: The fight against Nazism was over; now it was a war between the US and the USSR, Capitalist Democracies and Socialist Dictatorships.

Both the US and the USSR wanted a unified Korea, and both were proponents of self-determination, but neither wanted to cede its side to the other.

In 1946, the Russian Colonel General in charge of Korea, Shtykov, chose a man to lead their side of Korea: Kim Il Sung had fought the Japanese for ages in Manchuria and was trained by the Soviet Union’s military. The Russians “decided the election” and put Kim in power in the North.

In the South, the US wasn’t sure what to do, but it knew it shouldn’t give in to the Communists. So it kept managing Korea through the military, from Japan. Over time, policies in the North and South diverged.

The Soviets proposed a withdrawal from Korea and to let the Koreans decide. The US disagreed, fearing that Communist influence in the south could take over, and preferred to involve the UN, who proposed a vote. The USSR boycotted it: They had the boots on the ground, they were not going to risk losing that advantage with a vote, so they opted out. Only the South held elections.

But southern Koreans saw the writing on the wall: If we have elections just for the south, that’s the beginning of the end for a united Korea! A thousand years of unity, broken by foreigners! Many rebelled, to no avail. US and Korean forces crushed any rebellion. In May 1948, the South carried out elections, and the authoritarian Syngman Rhee won. In 1949, the US military exited South Korea.

The North saw this as the South drifting apart, both as a separate country and into capitalism. They didn’t want that. And now that the Americans had left, Korea was defenseless. Kim Il Sung asked Stalin for support for an invasion of the south. Stalin was hesitant, but thought: The US did nothing to prevent the fall of China to Communist hands. They will probably do nothing here, either?

Indeed, Communist China had just defeated the Nationalists, so it also thought the same would happen in Korea. Kim Il Sung paid a visit to China’s leader, Mao Zedong, to ask for his blessing in May 1950. Mao Zedong gave it. In June, North Korea invaded the South.

South Koreans were initially overwhelmed. They were cornered in the far south of the peninsula. The US had a decision to make. Should they leave the South Koreans to fend for themselves? Pave the way for a Communist takeover?

At this point, the US viewed Communism like Nazism or Japanese Imperialism: Ideologies that would continue to spread unless they were checked. It had already happened in Russia, then in Eastern Europe, then in China, and now in Korea. The earlier Communism could be stopped in Korea, the better. So this is when the US drew the line on the sand and it entered the war.2

Very quickly, the tides turned and the US and South Korea pushed north, nearing the Chinese border. US military leaders were jubilant: They thought they could beat Communism on the battlefield and that China wouldn’t dare to join the war.

But that was a miscalculation. China was now Communist, and had 2,000 years of influence over Korea. It could not let North Korea fall. So it sent nearly 1.5 million soldiers to the south.

They initially gained a lot of ground, moving the border south. But over time, the border returned to nearly where it was at the beginning of the war. In 1953, after over three million Koreans had died, North Korea and South Korea signed an armistice, and the border it established has been kept ever since.

Days When Centuries Happen

What would have happened if the US had developed the nuclear bomb weeks earlier?

Would it have had time to take over all of Korea?

What if Stalin had asked for four months to join the war against Japan, instead of three?

What if bad weather had not prevented the dropping of the first nuclear bomb? What if the Japanese had surrendered faster and the USSR could not have declared war against them and invade?

What if Seoul had been north of the 38th parallel? Would it be North Korean today?

We will never know, but it’s very possible that all of Korea would have remained intact.

Many questions remain about Korea:

Is the 1953 split between the north and the south a weird event in Korea’s history? No, it’s just a new instance of the same story repeating across the ages. Why? Because of geography.

What’s going on in North Korea? Why do so few people escape? Can it ever become normal?

Why has South Korean culture taken the world by storm?

What’s the future of the country, especially given its crazy fertility collapse?

These are some of the topics I’ll cover next in the Korean series. Subscribe to read them!

South Sakhalin and the Kuril Islands.

In fact it was the UN. The US was supported by several other countries, because this was a war of aggression from NK to SK, but 90% of the soldiers were either from the US or SK.

Thanks for this new focus of yours. There's quite a lot to discuss here. But I want to challenge one thing and add another. First: the suggestion that the Japanese were not ready to surrender isn't accurate. They were making overtures for a surrender via the Soviets (oops) and elsewhere. The US had broken the Japanese codes thru "Magic" intercept and the top leadership of the US knew this. The Japanese wanted a condition: to preserve the imperial throne. Some in the US leadership wanted to accept this (it might save US lives, for one thing). But the influential Secretary of State, J Byrnes, wanted to preserve 'unconditional surrender'. He won the argument. (Possibly, to make certain they didn't surrender before the USA had tried out the Bomb on a city -- unclear.) Secondly: It's not at all certain that the A-Bombs were decisive for the Japanese leadership. The firebombing of Japan had destroyed pretty much every city except four or five. For example, a Tokyo bombing in March killed more people in one night than would die later in Hiroshima. So the Japanese leaders (not an empathetic bunch) were used to cities disappearing in fire. Historians debate when the leadership first discussed the A-Bomb, but what is apparent is that the Soviet attack on Japanese-held territory (on the same day as the Nagasaki bomb) really focused their minds on surrender. And in the end, the USA agreed to keep the Emperor anyway! Likely, they could have had victory without the A-Bomb. But the narrative of saving 100s of 1000s of US lives continues to this day. And the Japanese preferred the idea that this 'cruel bomb' was what won the war, rather than the fact they were beaten before that. (I can send citations if you want.) Anyway, I look forward to the next article.

I´m glad that Tomas is back