Why Is Mexico City the Way It Is?

How Tenochtitlan Became Mexico City

This is the last article in the Mexico series. I lingered on the topic, but I really did want to get to this one because you can’t understand Mexico City (the biggest city in the American continent) otherwise. I think the link between Tenochtitlan and Mexico City is fascinating! I hope you enjoy it as much as I did writing it. Again, thanks to Shoni, Heidi, and MajoraZ for their help editing this article!

Why is Mexico city so populated?

Why is it sinking?

Why is it so prone to earthquakes?

Did the Spanish really destroy Tenochtitlan and rebuild a completely different city?

How can we see the ancient Tenochtitlan in present-day Mexico City?

The answers lie in why the Aztecs built Tenochtitlan the way they did, and the key to everything is water.

Why Was Tenochtitlan the Way It Was?

Here’s an overview of Tenochtitlan at the time of the Spaniards, to give you a feel for the city:

And this static picture contains nearly everything you need to understand why Tenochtitlan was built the way it was.

Here’s what you should notice:

Tenochtitlan is on a big island in the middle of Lake Texcoco

It has two urban centers (in white)

The periphery of the island is rather greenish

Causeways that double as dikes criss-cross the lake, connecting the island to dry land

There are additional dikes, notably the one to the right (east)

Why did the Aztecs build their city this way? You can tell by looking at the topography of the area:

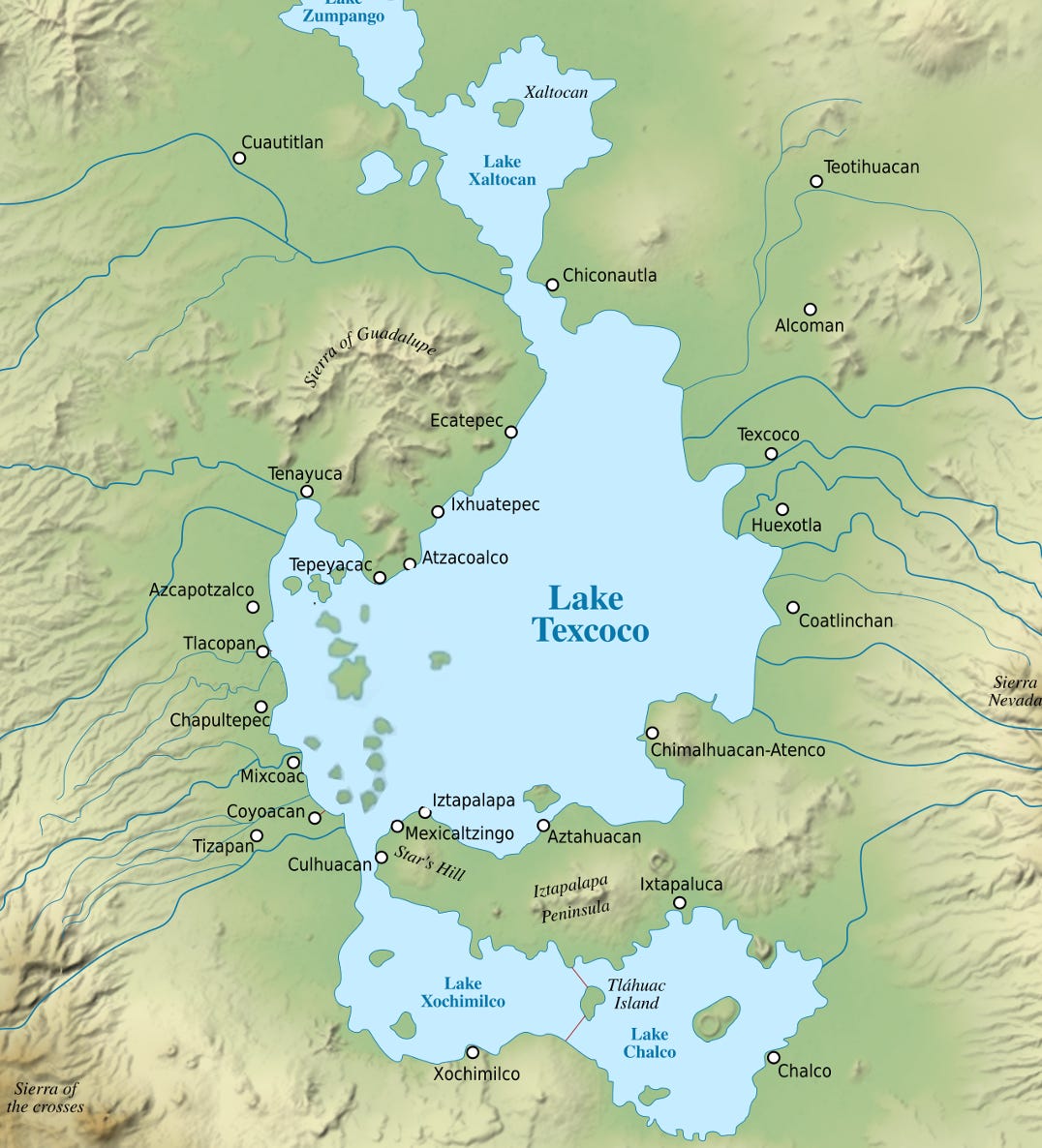

Nearly all the blue areas in the middle—the lowest-lying ones—were covered by lakes 500 years ago.

The Water of the Valley of Mexico

As we have seen, this region was rich with lakes because it was surrounded by ancient volcanoes that prevented water from escaping.

The lowest-lying lake was the central one, Lake Texcoco, which means all the water eventually ended up there.

This also means that lakes like Chalco and Xochimilco had fresh water, while Texcoco’s water was brackish: All these lakes were fed fresh water by surrounding rivers—bringing some salt with them—and as water evaporated, salt concentration increased. This saltier water would flow from smaller lakes into Lake Texcoco, continuously adding salt, while the upper lakes were replenished by fresh water.

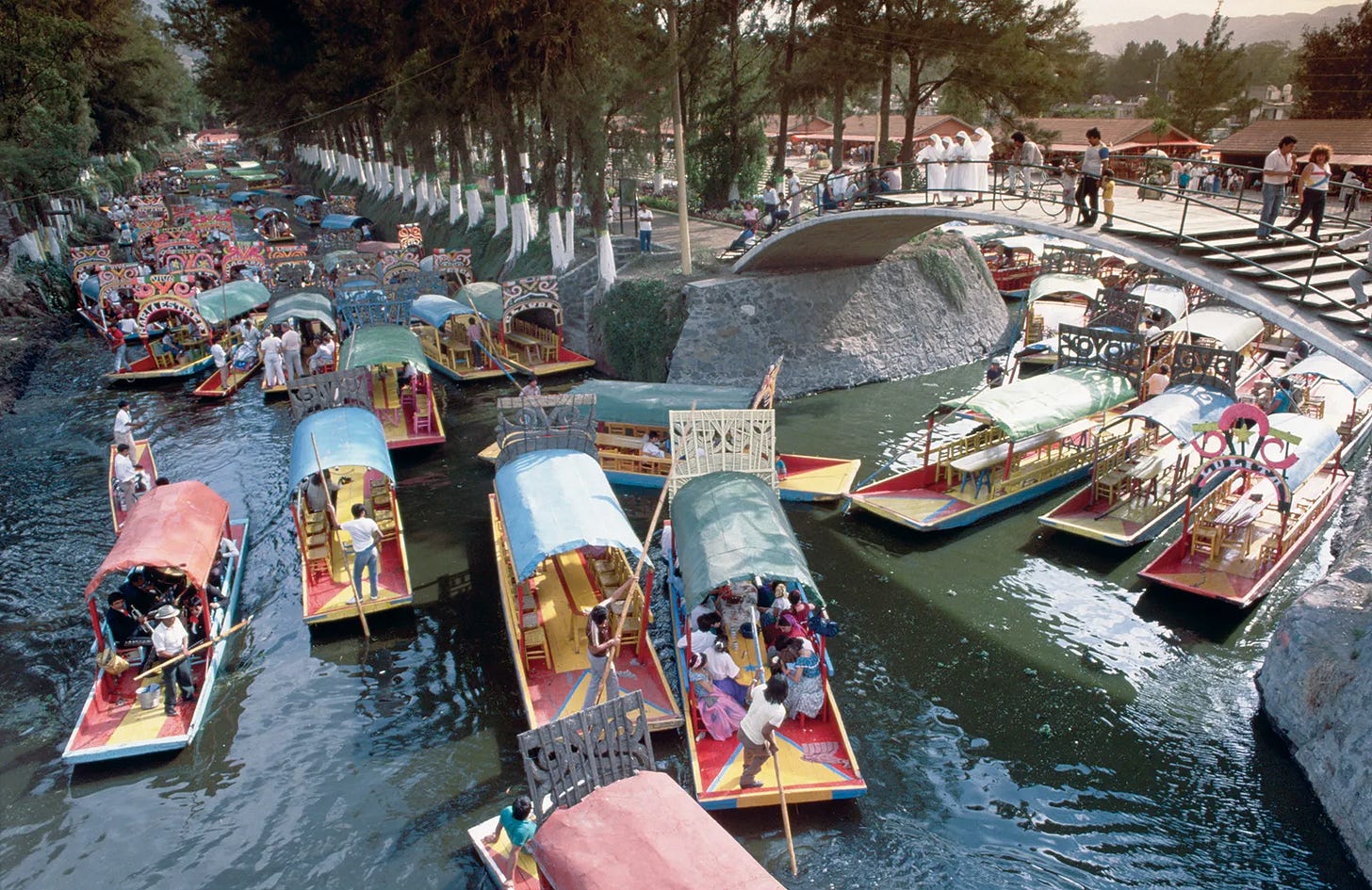

Having fresh water, the cities on the southern lakes built chinampas, plots of land built on the lake, for agriculture and residential land:

This is a more accurate representation:

Some of these chinampas can be seen to this day!

As we have seen, the chinampas were extremely fertile, yielding up to seven harvests a year. They were possible because these lakes were generally quite shallow (about 4 m, or 13 ft). It was easy to pile up mud and anchor it with reeds and by planting trees on the banks.

The chinampas had a beneficial side-effect: Transportation between them was by canoe, promoting a canoe culture. Since the Aztecs had no draft beasts or wheels for transportation, their only alternative on land was carrying goods on their backs. Canoe transportation was much better.

But for these laketop gardens to survive, the cities on the southern lakes—Xochimilco and Chalco—needed fresh water, yet sometimes their lakes became salty when the rainy season swelled Lake Texcoco and its brackish waters flooded them.

The southerners realized they had to stop Lake Texcoco from overflowing and built a causeway that doubled as a dike to cut off Lake Texcoco from Lake Xochimilco.1

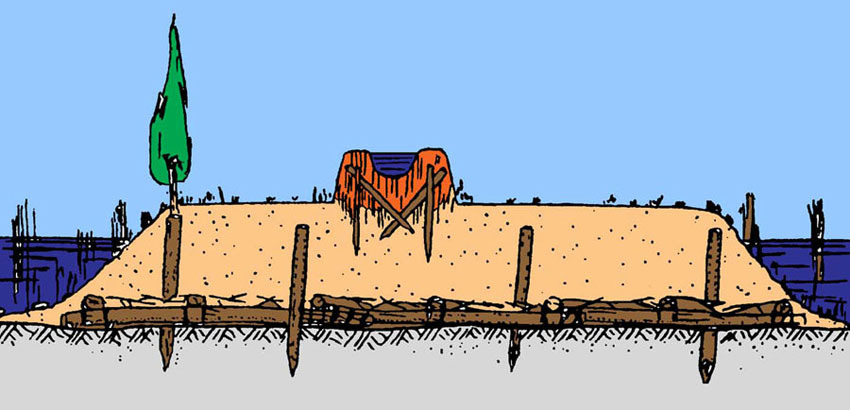

This is how large they could be:

This is a cross-section of a causeway:

Here with a bit more detail:

They were mixes of sand, lime, stone, and wood. Here’s a zoom into the dike core.

This causeway was located here:

This so-called dike of Mexicaltzinco sealed off and protected their freshwater system.

Now imagine you’re a Mexica, and you escape your enemies by settling on a forsaken island in the middle of a brackish, swampy lake.

What’s the very first thing you need to do?

Get fresh water to drink.

As you can see on the map, there are a few rivers close to the coast, to the west. Early on, the Mexicas had to canoe to the rivers, but eventually they wanted to build an aqueduct into the city. As we have seen, this request from the coastal neighbors sparked a war, which led to the formation of the Triple Alliance between Tenochtitlan, Tlacopan, and Texcoc, and the emergence of the Aztec state. What this means is that water was the direct cause of development, infrastructure, and conflict here. In other words, the local water setup demanded the emergence of a strong state, especially if it came from an island that didn’t have access to fresh water.2

As the Triple Alliance gained power, an obvious next target were the freshwater lakes to the south, full of chinampas that fed the valley. So they conquered them. Throughout this time, Tenochtitlan had been copying these chinampas, and I assume that accelerated after the conquest.

Over time, Mexicas had also been building their own causeways to reach the coast:

They would have realized that the water in enclosed parts of the lake between causeways became fresher over time, which accommodated chinampas. They also learned from the example of the southern lakes. So they started building more causeways for transportation and to section off parts of the lake to transform their salt water into fresh water.

Notice the dike at the right (east) of this picture, running north to south, and how it separates waters. That’s the famous dike of Nezahualcoyotl, which split Lake Texcoco in half and started making the waters of all Tenochtitlan even fresher:

In order not to impede the flow of water from western rivers into the Lake Texcoco, the Mexica ran canals west to east through their city; these proved useful for transport through the growing metropolis. Such a system of dikes and canals required constant maintenance and upgrading. This work was part of the labor obligation—a kind of tax paid by working—of many towns in the Valley.

Now remember I said they also had aqueducts to transport water from the springs to Tenochtitlan. Indeed, the water in the lakes became fresher with these dikes—good enough for agriculture, but not for drinking. So these causeways also transported fresh water!

This is a cross-section:

Notice in the previous illustration how there were bridges allowing canoes to pass—and to regulate the water levels.

In other words, the beauty of these causeways was that they had many functions:

Allow walking transportation across the lake

Shrink the area of the lake that was salt water and replace it with fresh water, which then allowed for chinampas, hence agriculture, and a much bigger population

Control floods, allowing swelling to be contained in Lake Texcoco

Bring freshwater from springs via aqueducts

Facilitate canoe traffic, crucial to cheap transportation (and therefore trade)

The importance of all this water management was evident to Aztec citizens, who experienced water every day—from canoe transportation, chinampa irrigation, fresh or salt water, and even floods that could swallow their streets, kill people, and carry away the adobe walls of their dwellings.

In the rainy summer months, Chalchiuhtlicue’s waters could break like an uncontrollable surge of amniotic fluid, invading the city, rushing down its streets, uprooting the carefully planted chinampas, washing away the adobe buildings that many called home.—The Death of Aztec Tenochtitlan, the Life of Mexico City, Barbara Mundy

And as I mentioned earlier, this type of public works was crucial to justify a quick emergence of a powerful state. Here’s one additional clue to that mechanism: Each one of these causeways carries the name of the ruler behind it.

Tlatelolco

Remember there were two urban centers in Tenochtitlan? The northern one was not Tenochtitlan, but Tlatelolco. It used to be a different island, inhabited by a different Mexica group, but eventually the populations merged and Tenochtitlan prevailed.

But the previous water barrier between the two was handy for traffic flow, as the Tlatelolco market became the biggest one in the Americas:

That market was huge:

We again turned our eyes toward the great market, and beheld the vast numbers of buyers and sellers who thronged there. The bustle and noise occasioned by this multitude of human beings was so great that it could be heard at a distance of more than four miles. Some of our men, who had been at Constantinople and Rome, and travelled through the whole of Italy, said that they never had seen a market-place of such large dimensions, or which was so well regulated, or so crowded with people as this one at Mexico.—Bernal Diaz del Castillo, one of Cortés’s soldiers.

According to him, you could find thousands of items in the market.3

Between 20,000 and 40,000 people visited the market daily—up to 60,000 on the special weekly market day.4

We’ve seen in previous articles that the best places for markets to emerge are where transportation is easy across regions. And since the Valley of Mexico was one of the most populous, with many cities on the lake banks and cheap water transportation, it turns out that an island in the middle of Lake Texcoco was the ideal place for a huge market to emerge—as long as the canoes could dock at the market itself.

My guess is that Tlatelolco specialized in the market, whereas Tenochtitlan specialized in administration, with the lake acting as a formidable defense for both.5

The Templo Mayor (a pyramid on a swamp!) was the main building in the city:

It’s very telling of the Aztec civilization that the two temples on top of this pyramid were dedicated to the gods of rain and war.

The palace of the rulers, last used by Moctezuma II, was adjacent to it.

Of course, it was lavishly decorated:

The city had been organized along a north-south / east-west grid for two reasons:

The orientation of the lakes, as Lake Texcoco was north of Lake Xochimilco, so fresh water flowed south to north from there, while the springs to the west meant fresh water flowed west to east.

Cosmology, which was very important to Aztecs6, and focused on natural phenomena like volcanoes (hence pyramids), rains, the Sun, and the Moon.

So now we have the key ingredients to understand why Tenochtitlan, a city of about 200k people, was the way it was:

Strong defenses from the lake

Water for irrigation, which allowed lots of agriculture through chinampas, which increased the size of the city

Causeways built for transportation, but doubling as dikes to manage water

Infrastructure works that facilitated the emergence of a strong state

Cheap transportation by canoes in a central part of the Valley of Mexico, making Tenochtitlan its central marketplace7

An orientation along north-south/east-west lines due to local geography and astronomy

Unfortunately, Spain is a dry country, astronomy is not as important in Christianity, and Spaniards barely cohabited with the Aztecs enough to understand how Tenochtitlan worked. Therefore, Spaniards understood very little of why the city worked the way it did. And so they changed the city, from a Tenochtitlan perfectly adapted to its surroundings, to a Mexico City that wasn’t.

Or so most people think.